Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.1 Medellín July/Dec. 2011

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES DERIVADOS DE INVESTIGACIÓN

Epidemiological profile of occlusion alterations in a school population in the Genoy township, municipality of Pasto, Colombia1

Jesús Solarte Solarte2, Ánderson Rocha Buelvas3, Andrés A. Agudelo Suárez4

1This research project was sponsored by the Comité Nacional de

Investigaciones —CONADI— of Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia.

2 Dentist. Specialist in Orthodontics and Maxillary Orthopedics.

Professor-researcher, School of Dentistry, Universidad Cooperativa

de Colombia-Pasto. E-mail address:jesus.solarte@campusvirtual.ucc.edu.co

3Dentist. Public Health Magister candidate, Universidad del Valle.

Professor-researcher, School of Dentistry, Universidad Cooperativa

de Colombia-Pasto. E-mail address: anderson.rocha@ucc.edu.co

4Dentist. Specialist in Health Services Administration. Ph.D. Public

Health. Professor at the School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia,

Medellín, Colombia. E-mail address: oleduga@gmail.com

SUBMITTED: JULY 21, 2011-ACCEPTED: SEPTEMBER 13, 2011

CORRESPONDING AUTHORSÁnderson Rocha Buelvas

Facultad de Odontología

Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, Sede Pasto

Calle 18 N.° 47-150

Pasto, Colombia

Teléfonos: (57-2) 731 48 76, 318 312 57 29

E-mail address:anderson.rocha@ucc.edu.coAndrés A. Agudelo Suárez

Departamento de Estudios Básicos

Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de Antioquia

Calle 64 N.° 52-59

Medellín, Colombia

Teléfonos: (57-4) 219 67 30

E-mail address:oleduga@gmail.com

Solarte J, Rocha A, Agudelo AA. Epidemiological profile of occlusion alterations in a school population in the Genoy township, municipality of Pasto, Colombia. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2011; 23(1): 111-125.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of occlusion alterations in a population of

schoolchildren between the ages of 5 and 16 years in the Genoy Township (Pasto), during 2010.

METHODS:a cross sectional study was

conducted in a sample of 439 children at the Institución Educativa Municipal Francisco de la Villota (public school) of the Genoy Township,

Municipality of Pasto (Colombia). A clinical exam was carried out and socio-demographic variables, presence of dental caries, arch

characteristics, right and left molar relationships for deciduous and permanent teeth, and occlusion alterations were recorded. A descriptive

analysis of total frequencies and by gender was conducted. Calculations of prevalence ratios (PR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI)

were made in order to estimate the association between gender and main occlusion alterations.

RESULTS: Caries prevalence was 88%. The occlusion alterations most frequently observed were anterior open bite (10%, more frequent in girls, with no significant differences) and

anterior crossbite (9.6%, more frequent in girls, with significant differences, p < 0.05). The most frequent habits were atypical swallowing

pattern (38%), pronunciation difficulties (19%) and nail biting (15%). Girls presented Class I molar relationship more frequently than

boys. Class II and III molar relationships were observed more frequently in males than in females.

CONCLUSIONS:some differences in the diagnosis of occlusion alterations were found by gender, being Class I, crossbite and anterior open bite the most common ones in girls.

Specific strategies are suggested in order to establish the principal risk factors for these alterations.

Key words:malocclusion, Angle classification, crossbite, open bite, occlusion.

INTRODUCTION

Malocclusions, along with other occlusion-related problems, represent some of the most common buccal alterations and they are, together with dental caries, periodontal disease, and the pain produced by these situations, some of the most frequent reasons for consultation in institutions that provide dental services.1 Dentists deal with these problems in their daily practice.2 Also, they are considered “alterations of civilization”, as they are very common in industrialized societies,3 although their presence in developing societies cannot be denied.

Occlusion and its multiple relationships are determined by intrinsic factors of size, shape, teeth eruption chronology, as well as by the shape of the dental arcade and craniofacial growth pattern.4 This variation in dentition is no more than the result of the interaction of genetic and environmental factors that determine the occlusal relationships since the moment of prenatal development, and even in the postnatal phase.5 Nevertheless, these problems are usually less inspected from the perspective of public health, although they affect general welfare, due to the economic and social costs that considerably decrease the persons’ quality of life.6, 7

Epidemiological studies on this topic have demonstrated that malocclusion occurs with a relatively high prevalence.5, 8, 9 For example, it has been reported that in the municipality of Cáceres, Brazil, approximately 31.2% of the kids presented mild occlusion problems, while 2.4% of the cases were moderate to severe.10 The latest National Study on Oral Health (ENSAB III) revealed some important characteristics related to occlusion in 12-year-old children of both sexes, such as: Prevalence of anterior crossbite, 3.4%; anterior open bite, 7.4%, posterior crossbite, 3.7%, mainly unilateral. Both anterior and posterior crossbite have greater prevalence in women.11

All this suggests the necessity of planning and executing preventive orthodontic treatments and other procedures in order to generate an oral environment favorable to the normal development of occlusion,10 as well as the need of making a rational planning of orthodontic measures3.

From the perspective of public health, it is very important to recognize the specific conditions of the diverse social groups, especially of those that are in real economic, social, or educative disadvantage —to name just a few—. One of the most appropriate approaches suggests the study of social determinants as proposed by the World Health Organization. According to this model, belonging to a given ethnic group, social class or gender constitutes a structural determinant of health inequities.12 The case of the Genoy township, in the municipality of Pasto (Colombia), refers to the ethnical resurgence of a community situated in Southeastern Colombia, whose resettlement is due to living near Galeras, the most active volcano in Colombia.13

Like this community, there are many other minority ethnic groups in Colombia whose occlusion problems have not been adequately treated, especially as the General System of Social Security in Health (Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud) does not include dental attention for these problems as part of its assistance plans. This is why it is important to design epidemiological profiles, in order to suggest alternatives in preventive and interceptive orthodontics for unattended communities. The objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of occlusion alterations in schoolchildren between 5 and 16 years of age in the Genoy Township (Pasto) during 2010.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was carried out, by selecting all of the students officially listed at the Institución Educativa Municipal Francisco de La Villota (public system) at the Centro, Villa María, Charguayaco, and Pullitopamba districts of the township of Genoy, Pasto (Colombia), who were registered in the courses of transition to fifth grade.

In general, the population under study had not been subjected to previous treatment, nor to current orthopedic or orthodontic treatment; they did not have dentoalveolar or craniofacial traumas, and did not suffer systemic diseases that would affect their corporal development and growth. Although 441 children fulfilled the conditions for this study, two kids from third grade were excluded from the final analysis because, even though some variables of their dental examination had been measured, the information could not be completed in total due to lack of collaboration on their part. Finally, the population included in the analysis was comprised by 439 kids (228 girls), which represents 99.5% of the total.

An evaluation instrument (available if requested from the authors) was used, including variables of identification, as well as the ones related to the dental examinations, and to the habits considered as a risk of developing occlusion problems. For this study in particular, the following variables were included: Age (actual years), school grade (transition to fifth grade), type of dentition (deciduous, mixed, permanent), presence of caries (this was determined by visual inspection at the time of examination), presence of both upper and lower primate space (yes/no), shape of both upper and lower arch (triangular, ovoid, squared), symmetry of the arches (yes/ no), anterior, posterior, left and right crossbite (yes/no), anterior, posterior, left and right open bite (yes/no), deep bite (yes/no). Concerning the variables related to habits, the following were included: type of breathing (by means of the labial seal test and Rosenthal reflection, and it was classified as oral, nasal, or mixed), type of swallowing (determined by the existence of facial muscles activity, full dental seal, and labial seal, and it was classified as mature and atypical), labial competence, labial suction, digital suction, nail biting, object biting. All of these were classified according to the existing literature.14 Similarly, classification of deciduous molars15 (mesial, distal, straight terminal plane) and molar relation (Angle Class I, II, and III) 16 was performed.

Data collection, including the respective tooth examination, was carried out by 30 students from the School of Dentistry (UCC-Pasto), who were attending the Growth and Development clinical courses, under constant supervision of an odonto-pediatrician and an orthodontist.

These students received practical and theoretical training for each of the variables included in the tooth examination. A simple concordance analysis was performed for each variable, and the study was judged convenient as a global level of agreement of more than 75% was found among both the dentistry students and the supervisors. Once the field work had been completed, the data went through quality control, by checking possible inconsistencies among the collected information and the instruments. These data were systematized in Excel® for Windows®.

A descriptive analysis was performed on the frequency of the aforementioned variables, including all the school population sorted out into boys and girls. Chi-square statistical significance tests were performed in order to observe percentage distribution differences among the variables. In the case of molar relationship, both deciduous and permanent, the percentages and Chi-square test were calculated in order to observe the proportional difference between both sexes. Regarding the principal occlusion alterations, prevalence ratios (PR) were calculated by means of 2 x 2 simple contingency tables with their respective confidence intervals to 95% (95%CI). For the epidemiological and statistical data analysis, these software were used: SPSS 17.0 (Chicago IL. USA) and Epidat 3.1 (Dirección Xeral de Innovación e Xestión da Saúde Pública, Xunta de Galicia, España, Pan American Health Organization and Instituto Superior de Ciencias Médicas, La Habana).

This study was approved by the Health Sciences Research Committee of Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, and compliance with the requirements for research in health was guaranteed (Resolution 008430 of 1993). Informed consent letters were obtained and confidentiality/anonymity of the collected information was assured. This study does not present risks for the physical, mental or social health of the participants. In the presentation of results, the group of researchers decided to incorporate the gender perspective, by using an inclusive language and therefore avoiding gender-biased language when referring to children of both sexes, especially in the Spanish version of this article.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population. In general, kids younger than 10 years participated more frequently. Distribution by grades is rather homogeneous. More than 80% of the kids present mixed dentition, and caries prevalence is 88%. No significant differences were found in the percentage distribution of each of the variables selected by sex.

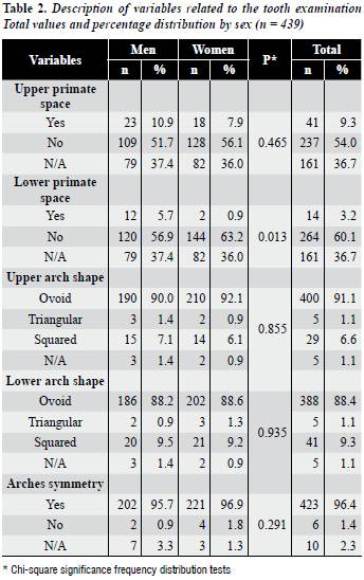

Considering the clinical evaluation of upper and lower arches (table 2),more than half of the population does not have upper primate space, and 60% does not present lower primate space, being more frequent in girls. In this case, statistically significant differences per sex were found (p = 0.01). Although most of the population presented upper arches with ovoid shape, a slightly higher percentage of the kids presented squared shape. In the case of the lower arch, no great differences were observed by sex. 2% of the girls presented arch asymmetry compared to 1% of the boys, although with no significant differences (p = 0.291).

Analysis of the principal occlusion alterations in the population of children under study (table 3) showed that prevalence of anterior crossbite, posterior right crossbite, anterior, posterior right and left open bite is higher in girls, although with no statistically significant differences, except for anterior crossbite (PR 1.86; 95%IC 1.00-3.42). In terms of posterior left crossbite and deep bite, the prevalence was higher in boys, but without significant differences.

Concerning the percentage distribution of the different oral habits (table 4), the most frequent were: Atypical swallowing (38%), difficult pronunciation (19%), nail biting (15%), and labial incompetence (15%). In these cases, the highest frequency of the habits occurred in girls. In other cases analyzed, such as oral respiration habits and unilateral mastication, the highest frequency occurred in boys.

Concerning the different types of molar relationships in deciduous and permanent dentition (table 5), right and left mesial step occurred more frequently, especially in boys, although the differences were not statistically significant in comparison to the girls (p = 0.122 in right molar relationship and p = 0.252 in left molar relationship). These schoolchildren presented distal step more frequently, with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

And they also presented molar relationship Class I, both right and left, more frequently. The kids presented a higher proportion of molar relationship Class II and Class III alike (right and left), and no statistically significant differences were observed.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study account for a population with high prevalence of dental caries, in which girls presented lack of inferior primate space more frequently, with significant differences in comparison to boys. In general, the kids also presented high prevalence of anterior crossbite, posterior right crossbite, anterior, posterior, right, and left open bite, but with no significant differences. This situation was also observed when analyzing some oral habits such as atypical swallowing, difficult pronunciation, nail biting and labial incompetence. Similarly, some differences between the two sexes were observed in terms of molar relationship both right and left but with no statistically significant differences, except in the case of distal step in deciduous molar relationship.

The results of this study are not easily comparable to the ones obtained by the ENSAB III,11 because the latter only included results for population of 12 years or older. In general, they found a prevalence of 15.1 and 9.5% of upper and lower spaces respectively, which is slightly higher than the one reported for the children population of the township of Genoy. The prevalence of anterior crossbite was of 3.4% at the age of 12, which is significantly lower than the one reported for the reindigenized children population (9.6%). Regarding posterior crossbite, Colombian teenage population presented a prevalence between 3.7 and 4.6%, which is higher than the one found in the study in Pasto (Nariño), with some differences by sex. The percentages of anterior and posterior open bite were higher than the ones found by the ENSAB III. In any case, these percentages must be carefully interpreted, since no significant differences exist between the populations of both studies.

It is important to note the lack of knowledge about the prevalence of malocclusions in specific populations. For example, a study carried out in an indigenous population of Peru,17 with physical characteristics similar to the ones of this study in the township of Genoy, found out a prevalence of anterior crossbite of 17.4% (higher in boys); posterior cross bite, 3.0% (lower in girls) and anterior open bite, 3.2% (higher in girls).

In general, children of the township of Genoy presented better global indicators, but some differences were observed, such as anterior crossbite, with higher prevalence among girls. This is why typical genetic characteristics of these communities must be taken into account in this type of studies. There are specific differences with other studies carried out in Venezuela,9 Mexico,18 Brazil,19,20 Cuba,10 and other countries with contexts similar to those of Colombia.21, 22

It is important to keep in mind that genetic characteristics of this population, membership to a given ethnic group, growth and developmental particularities— expressed by clinical characteristics in the oral cavity—and other exogenous factors that determine the access to oral health services directly affect the interceptive and corrective orthodontics services.12, 13, 23, 24

Even though caries and periodontal disease have an important place in the public health agenda due to their magnitude and severity, incorporation of the human development perspective allows recognizing the clinical manifestations that, just like occlusion alterations, have a great impact in the quality of life and well-being of children and adolescent populations, affecting their esthetics and functionality,6 as well as their psychological impact and their selfsatisfaction. 25 It is important to realize that ethnic group,2, 26, 27age,2, 28 and sex2, 29 are important elements related to the buccal epidemiological profiles, and in this particular case to the ones connected to occlusal alterations.

It is important to mention the strengths and weaknesses of this study. A prominent strength is the epidemiological characterization of a sample population with a social perspective, as well as the standardization of data collection instruments by means of simple concordance analysis to calibrate the persons who conducted the customary clinical examinations, as well as a consistent sample with a more equitable distribution by sex. Nevertheless, it is important to consider the limitations of this project in terms of interpretation of the results. In the first place, the study was carried out in a specific education institution; on the other hand, the methodological design does not allow making inferences to the population, neither to the city of Pasto nor the department of Nariño.

Nevertheless, it is important to point out that the general objective of this study was to identify the particular conditions of a specific community based on the analysis of related factors. Finally, being a universal study, causality may not be established; it would only be achieved with a cohort of patients in order to observe the changes over time and thus approach new hypothesis. For these reasons, this investigation group will assess the principal associations between buccal habits and occlusion alterations by means of multivariate models in another publication.

New studies are needed in relation to the principal occlusion alterations in other specific groups. It is also important to be aware of other elements that may be associated, such as: knowledge, attitudes and practices, perceptions on one’s health conditions, economic factors, and possibilities of accessing health services. Other variables related to life quality and its relation with oral health are also of interest. Complete dental attention from a clinical and epidemiological approach would allow identification of the principal social determinants associated to occlusion alterations,30 as well as to the establishment of comprehensive actions of promotion and prevention, and preventive and interceptive orthodontics programs aimed at populations of scarce resources.

Conflict of interests: none.

1. Botero PM, Vélez N, Cuesta DP, Gómez E, González PA, Cossio M et al. Perfil epidemiológico de oclusión dental en niños que consultan a la Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia. Rev CES Odont 2009 22(1): 9-13. [ Links ]

2. Nieto García VM, Nieto García MA, Lacalle Remigio JR, Martín LAK. Salud oral de los escolares de ceuta. influencias de la edad, el género, la etnia y el nivel socioeconómico. Rev Esp Salud Pública 2001; 75: 541-550. [ Links ]

3. Fernández Torres CM, Acosta Coutin A. Estado actual de la atención a escolares de primaria. Rev Cubana Estomatol 2007; 45(1): 91-95. [ Links ]

4. Bishara S, Hoopens B, Jakobse Jr, Kohout F. Changes in the molar relationship between the deciduous and permanent dentitions: a longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988; 93(1): 19-28. [ Links ]

5. Kerosuo H, Laine T, Kerosuo E, Ngassapa D, Honkala E. Occlusion among a group of Tanzanian urban schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1988; 16(5): 306-309. [ Links ]

6. Taylor RK, Kiyak A, Huang GJ, Greenlee GM, Cameron JJ, King GJ. Effects of malocclusion and its treatment on the quality of life adolescents. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 136(3): 382-392. [ Links ]

7. Agou S, Locker D, Streiner DL, Tompson B. Impact of selfesteem on the oral-health-related quality of life of children with malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008; 134(4): 484-89. [ Links ]

8. Guaba K, Ashima G, Tewari A, Utreja A. Prevalence of malocclusion and abnormal oral habits in North Indian rural children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 1998; 16(1): 26-30. 9. Medina C. Prevalencia de maloclusiones dentales en un grupo de pacientes pediátricos. Acta Odontol Venez 2010; 48(1): 1-19. [ Links ] [ Links ]

10. Isper Garbin AS, Saliba Garbin CA, Pantaleao Dos Santos MR, Elaine Goncalves P. Prevalencia de maloclusión en la dentición primaria en el municipio de Cáceres, Brasil. Rev Cubana Estomatol [revista en línea] 2007; [fecha de acceso 25 de julio de 2011]; 45(1) URL disponible en:http://scielo.sld.cu/ [ Links ]

11. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. III Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal, 1998. Bogotá: Ministerio de Salud; 1998. [ Links ]

12. World Health Organization (WHO). A conceptual framework for action on social determinants of health. [en línea] 2007 URL disponible en:http://www.who.int/social_determinants/ resources/csdh_framework_action_05_07.pdf [ Links ]

13. Colombia. Departamento Nacional de Planeación. Lineamientos de política para implementar un proceso de gestión integral del riesgo en la zona de amenaza volcánica alta del Volcán Galeras. Documento CONPES 3501. Versión para discusión. Bogotá: El Departamento, 2007. [ Links ]

14. Ovsenik M, Farcnik FM, Korpar M, Verdenik I. Follow-up study of functional and morphological malocclusion trait changes from 3 to 12 years of age. Eur J Orthod 2007; 29(5): 523-529. [ Links ]

15. Williams DR, Valverde R, Meneses A. Dimensiones de arcos y relaciones oclusales en dentición decidua completa. Rev Estomatol Herediana 2004; 14 (1-2): 22-26. [ Links ]

16. Angle EH. Classification of the teeth. Dental Cosmos 1899- 41: 248-264, 350-357. [ Links ]

17. Aliaga-Del Castillo A, Mattos-Vela MA, Aliaga-Del Castillo R, Del Castillo-Mendoza C. Maloclusiones en niños y adolescentes de caseríos y comunidades nativas de la Amazonía de Ucayali, Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública 2011; 28(1): 87-91. [ Links ]

18. Murrieta Pruneda JF, Cruz Díaz PA, López Aguilar J, Marques Dos Santos MJ, Zurita Murillo V. Prevalencia de maloclusiones dentales en un grupo de adolescentes mexicanos y su relación con la edad y el género. Acta Odontol Venez 2007; 45(1): 74-78. [ Links ]

19. Brito DI, Dias PF, Gleiser R. Prevalência de más oclusões em crianças de 9 a 12 anos de idade da cidade de Nova Friburgo (Rio de Janeiro). R Dental Press Ortodon Ortop Facial 2009; 14(6):50-57. [ Links ]

20. Marques LS, Barbosa CC, Ramos-Jorge ML, Pordeus IA, Paiva SM. Prevalência da má oclusão e necessidade de tratamento ortodôntico em escolares de 10 a 14 anos de idade em Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brasil: enfoque psicossocial. Cad Saude Publica 2005; 21(4): 1099-1106. 21. Behbehani F, Artun J, Al-Jame B, Kerosu H. Prevalence and severity of malocclusion in adolescent Kuwaitis. Med Princ Pract 2005; 14(6): 390-395. [ Links ] [ Links ]

22. Saleh FK. Prevalence of malocclusion in a sample of Lebanese schoolchildren: An epidemiological study. East Mediterr Health J 1999; 5(2): 337-343. [ Links ]

23. Proffit WR. Ortodoncia contemporánea: teoría y práctica. 3.ª ed. Madrid: Elsevier; 2001. [ Links ]

24. Almeida RR, Almeida PRR, Almeida MR, Garib DG, Almeida PC, Pinzan A. Etiologia das más oclusões: causas hereditárias e congênitas, adquiridas gerais, locais e proximais (hábitos bucais). Rev Dent Press Ortodon Ortop Maxilar 2000; 5(6): 107-129. [ Links ]

25. Xiao-Ting L, Tang Y, Huang XL, Wan H, Chen YX. Factors Influencing Subjective Orthodontic Treatment Need and Culture-related Differences among Chinese Natives and Foreign Inhabitants. Int J Oral Sci 2010; 2(3): 149-157. [ Links ]

26. Rosa RA, Arvystas MG. An epidemiologic survey of malocclusions among American Negroes and American Hispanics. Am J Orthod 1978; 73(3): 258-273. [ Links ]

27. Alkhatib MN, Bedi R, Foster C, Jopanputra P, Allan S. Ethnic variations in orthodontic treatment need in London schoolchildren. BMC Oral Health 2005; 27(5): 8. [ Links ]

28. Thilander B, Pena L, Infante C, Parada SS, de Mayorga C. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in children and adolescents in Bogotá, Colombia. An epidemiological study related to different stages of dental development. Eur J Orthod 2001; 23(2): 153-167. [ Links ]

29. Ciuffolo F, Manzoli L, Dattilio M, Tecco S, Muratore F, Festa F et al. Prevalence and distribution by gender of occlusal characteristics in a sample of Italian secondary school students: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Orthod 2005; 27(6): 601-606. [ Links ]

30. Vázquez Amoroso LM, Antelo Vázquez L. La prevención de las maloclusiones en el contexto social. Enlace [revista en línea] 2009 [Fecha de acceso 6 de junio de 2011] 15(91) URL disponible en: http://enlace.idict.cu/index.php/enlace/ article/viewFile/124/118 [ Links ]

text in

text in