Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.1 Medellín July/Dec. 2011

LITERATURE REVIEW

A review of the literature on the causal relationship between occlusal factors (ofs) and temporomandibular disorders (tmds). vi: final conclusions

Rodolfo Acosta Ortiz1

1OD, MS, Adjunct Professor, Department of Prosthodontics, College of Dental Medicine, Nova Southeastern University. Dentist - Universidad del Valle. Advanced Clinical Training in Temporomandibular Disorders and Orofacial Pain; MSc with emphasis in Epidemiology, University of Minnesota, USA.

RECIBIDO: SEPTIEMBRE 21/2010-ACEPTADO: MARZO 18/2011

CORRESPONDING AUTHORRodolfo Acosta Ortiz

Department of Prosthodontics

College of Dental Medicine

Nova Southeastern University

3200 South University Drive

Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33328

Phone number: 954 262 73 43.

Fax number: 954 262 17 82 954 262 17 82

E-mail address: acostaor@nova.edu

Acosta R. A review of the literature on the causal relationship between occlusal factors (OFs) and temporomandibular

disorders (TMDs). VI: final conclusions. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2011; 23(1):126-157.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION:this is the sixth and last article of this extensive and complete literature review which purpose was to evaluate

the possible causal relationship between occlusal factors (OFs) and temporomandibular disorders (TMDs).

METHODS: of all the articles found, only the analytical epidemiologic studies were included, and they were analyzed by means of the epidemiologic criteria commonly used to establish causality (cause/effect).

RESULTS: the findings suggest that, although the first criterion —strength of the associations between

OFs and TMDs— existed, other criteria such as consistency with other studies, temporal sequence of events, dose-response relation and

biologic credibility cannot be supported with the current available scientific information. Therefore, if there is a causal relationship, it is a

weak one.

CONCLUSION:with the scientific information available today, evidence of a causal relationship between OFs and TMDs is weak and

confusing. More and better studies are needed, with improvement of research methods. This will pave the way for clearer and more concrete

results that will also help to make more solid interpretations and conclusions about the possible causal relationship between OFs and TMDs.

Key words:occlusion, temporomadibular disorders, etiology, dental occlusion, occlusal factors, temporomandibular joint, occlusal adjustment, orthodontic treatment, causality.

INTRODUCTION

Historically, the relationship between occlusal factors (OFs) and temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) has been a clinical event known by dentists for a long time but, despite many years of research, the possible causal or etiological relationship between OFs and TMDs is not clear and remains a controversial topic in the dental profession. Since the establishment of a causal relationship (cause/effect) is not a simple, obvious and direct task, and can only be achieved by having into account all and the best possible scientific evidence currently available, in this literature review about OFs and TDMs,1-5 the studies were presented and analyzed in the context of scientific evidence. This review started by analyzing the descriptive studies1 (transversal studies and case series), then the analytical studies were reviewed:2 case and control studies (CCS), longitudinal studies (LS), and clinical studies (including randomized clinical trials, RCTs) in which experimental occlusal interferences (EOI) were used.3 Finally, by using the same methodology, an analysis was made on the role of occlusal adjustment (OA) by selective grinding4 and orthodontic treatment5 (OT) as preventive or therapeutic means of TMDs treatment or as an etiologic factor in the case of OT. The sixth and last article of this review will present and analyze all the literature available, with the criteria commonly used to establish causality in the field of epidemiology,6-8 trying to produce a well-balanced and clear conclusion about the possible causal relationships between OFs and TMDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The main support of the reports presented and analyzed in this article is based on the previous publications made in this series of articles.1-5 Nevertheless, in order to update such information, the literature of the previous five years has been reviewed again with the same methodology used in the preceding publications.1-5 This literature update was made by using different sources of information:

- The Medline standard medical information database, specifically the MedlineOVID bookstore (since 2004 until 2009). Abstracts in the English language were reviewed as well as the titles that suggested the study of the relationship between occlusal factors, occlusal interferences (OIs), EOI, OA, OT, and TMD. The key words used to perform the search were the diverse OFs and relevant terms under the heading occlusion/malocclusion, as well as OI, OA, and occlusal therapy (OT), which were intertwined with relevant terms under the heading TMD and temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJ).

- The bibliographic references of the articles initially found during the MedlineOVID database search.

- The bibliographic references of diverse books in the field of TMD, TMJ dysfunction, and dental occlusion.

- The bibliographic references of diverse literature reviews about the topic under study, found in the MedlineOVID database. >

In order to focus and strengthen this review, studies of less strength in the scale of scientific evidence (descriptive studies) were excluded, and the analysis only included analytical epidemiological studies (CCS, LS, and RCT) that allowed obtaining their respective measures of association odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR), either because the articles themselves offered them or because their data allowed the calculations. These measures of association will be discussed later.

Epidemiological concepts used to evaluate causality

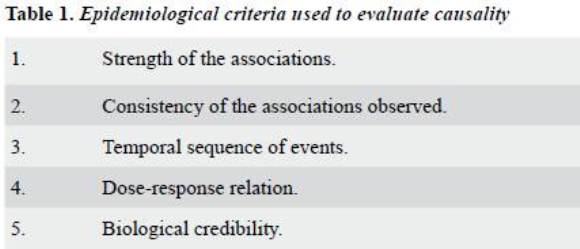

In order to make adequate evaluation of the possible causal relationships between dental occlusion/OF and the TMDs, the criteria used in the field of epidemiology to establish causality as recommended by Hennekens (1987)6 were adopted. These parameters are displayed in table 1 and even though they will be briefly described, the reader is invited to review additional complementary references.6-8

- Strength of the associations. The magnitude of the association observed is useful to determine the probability of the exposure factor alone affecting or increasing the risk of developing the disease. The greater association strength the greater probability of the exposure factor having actual participation in the development of the disease, and the minor probability of the relation being due to unsuspected or uncontrolled variables of confusion; and therefore, the greater possibility of establishing causality. The measures of association more generally used are odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR).6- 8 Simply put, when one of these indicators show a value of 10, it is twice as strong compared to the value of 5. The value of 1 is considered neutral and it indicates that the exposure factor does not increase nor decrease the probability of developing the disease. A value of < 1 indicates that the factor under evaluation protects against the disease, or better, decreases the risk of developing the disease. Arbitrarily, values between > 0,5 and < 2 are not considered of great strength and therefore are considered marginal or weak values of association. The OR is usually calculated from the CCS and the RR is usually calculated from the LS. The RCT are a form of LS in which the research variables are handled; in the epidemiological field, they are the closest form to a lab experiment, and therefore constitute the best experimental evidence. The association of causality produced by this type of studies strengthens the causal relationship between the exposure factor and the disease. Measures of association similar to the RRs can also be obtained from these studies in order to demonstrate the degree of relation between the exposure factor and the disease.

- Consistency of the associations observed, in relation to other studies. When the studies are conducted or repeated in other laboratories or clinics at different moments, using alternative methodologies in a variety of cultural and geographical settings, it may be assured that the phenomenon is not specific of the researchers or their environment, so that the validity of the research hypothesis or the clinical causality premise may be more easily accepted.This is of the upmost importance because epidemiology is an inexact science in which it is impossible to control variables just as it is done in a laboratory. Therefore, replication of the studies is probably the most persuasive evidence to support a causal relationship in a clear and evident manner. This review will start referring to consistency when at least two studies produce similar data or with the same tendency. Nevertheless, it should be taken into account that, although certain association values may eventually reappear, and therefore be considered consistent, such values should ideally come from different research groups, conducted in different settings, and with different methodologies. When a single research group comes to the same findings, the principle of consistency is under risk and the causal relationship loses support.

- Temporal sequence of events. For an exposure factor to cause a disease, it should necessarily occur before —and not after— development of the disease. Although it is not usually easy to establish the existence of an appropriate temporal sequence of events, it is obvious that the conclusion of causality improves as the exposure factor precedes the disease in a period of time that fits the known or supposed biological mechanism. Although strong and consistent associations may occur, the only way of accepting OFs as causing TMDs is by clearly showing that any of the studied OFs (in this case the exposure or risk factor) precedes the emergence of TMDs (in this case the disease). This leads to think that, in terms of establishing causality, RRs are more important than ROs. The latter are calculated from CCS, which are static studies over time in which the risk factors and the disease itself are not monitored. Therefore, it can’t be easily established whether the exposure factor preceded the disease or if, on the contrary, the exposure factor is a consequence of the disease. On the other hand, RRs are calculated form LS, in which the risk factors and the disease itself are monitored, and therefore one can be sure about which of them happened first. As previously mentioned, although CCS enable establishing associations between the exposure or risk factors and the disease, they do not allow clarifying which ones go first, as both factors are studied at static points of time. Therefore, LSs and RCTs are the only type of studies by which one can be sure that exposure factor precedes disease development.

- Dose-response relation.Establishing a relationship between intensity, quantity, frequency, and duration of the exposure factor and the risk of developing the disease would strengthen the causal relationship. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the dose-response relation is not usually a one to one correlation; besides, the absence of a dose-response relation does not imply the absence of causality. Therefore, the presence or absence of a dose-response relation should be evaluated in light of other alternative explanations and taking into account the criteria previously analyzed.

- Biological credibility.A causal relationship becomes stronger in the presence of a known or supposed biological mechanism by which the exposure factor may reasonably alter the risk of developing the disease. Biological credibility depends at a given moment on the current state of the art; therefore, the fact of not knowing a biological mechanism to explain the statistic association that implies the presence of causality does not necessarily mean that causality does not exist.

RESULTS

54 analytical studies were found, obtaining OR (table 2)9-46 and RR (table 3)47-63 from them as measures of association. These studies were sorted out and arranged in tables specifying the following: Methodological aspects, specific factors considered as exposure factors [morphologic (static) and functional (dynamic) OFs], diseases [myalgia, myofascial pain (MPS), disc displacement (DD), arthritic disorders (ADs), or signs and symptoms (SS) of TMD (SSTMD)], and the values related to the number of participants in each study with or without the disease/diagnostics presenting the exposure factor (tables 2 and 3). The latter allowed calculations of the association values, which were also presented.

Also, the values of the statistical associations reported in each publication were included. Finally, this information was also rearranged and separately presented for each OF, in relation to the different TMD conditions. The overall average (OA) of the different values of association was also calculated (table 4). Although arbitrary, this overall average helps to estimate or demonstrate a tendency of the global strength of each OF in relation to the SSTMDs or to TMD diagnostics sub-groups. In order to simplify the information, certain conditions that presented similar characteristics or were closely related were also grouped. Degenerative articular diseases, such as osteoarthrosis, osteoarthritis, and polyarthritis, were included as part of the AD group. Articles reporting information on premature contacts (PC) were analyzed along with the ones containing information on centric displacement (CD) because, clinically, CD cannot occur without the existence of at least one PC. Similarly, reports containing information about occlusal stability or posterior support were put together, because clinically both of them present less quantity of teeth in contact.

Analysis of the epidemiological concepts used to evaluate causality

- Strength of the associations.As shown in table 4, the only factor that presented an almost neutral overall average (OA) in the morphologic OFs was midline discrepancies (OA = 1.2). Nevertheless, many of these OFs presented strong values, such as horizontal overbite (HO) > 4 mm (OA = 5.0), open bite (OA = 7.6), crossbite (OA = 3.8), and vertical overbite (VO) > 4 mm (OA = 3.4), while others presented weaker values, such as Class II (OA = 2.8) and lack of occlusal stability (OA = 2.0). In functional OFs, the CD/PC presented a marginal association (OA = 2.0); however, this value seemed to be more related to the presence of SSTMD, as slightly higher values are observed when the ORs/RRs of muscular disorders (2.3)11, 32 or ADs (2.8)11, 24 are averaged. A similar situation occurred with non-working side interferences (NSIs): although their association odds average wasn’t strong (OA = 1.6), their relationship to MPS (OA = 2.5)32 and ADs (5.0)16 was reported as higher. On the other hand, working side interferences (WSIs) presented a strong association value (OA = 4.3); however, this value was calculated from only two reports which also analyzed two different conditions of TMD (MPS and SSDTM).31, 32 The anterior and canine guides presented an almost neutral association average value (OA = 1.2), while the group function displayed an OA of the association value that, although marginal, was inverse (protective) to the presence of SSTMD (OA = 0.62). The Occlusal Adjustment and the OT relation to the TMDs has marginal values of association (OA = 0.74 and OA = 1.2, respectively).

- Consistency of the associations observed, in relation to other studies.Although different association measure values showed several OFs associated to the TMDs, consistency of the results was proved only in a few cases (tabla 4). In many cases the data were generated by the same group of researchers, without records from other investigators or research projects. In several occasions, if the values came from different research projects, the reported association values were contradictory.(tabla 4). Class II was associated to SSTMDs (OR: 3.1)20 and to ADs of TMJ (OR: 3.6);13 nevertheless, another report revealed no association with SSTMDs (OR: 1.0); no more information regarding ADs was found. Open bite was consistently associated to ADs of TMJ (OR: 15.9; 7.7; 17.8)11, 18, 24 and to myalgia (OR: 6.0; 7.55);11, 17 however, this information was reported by the same group of researchers. The same group of researchers also reported association between crossbite and the different types of DD (OR: 2.0; 3.33; 2.64; 10.3; 11.67).11, 17, 18, 24, 25 In relation to the SSTMDs and this OF, two studies reported inverse association values (OR: 0.35; 0.27),12, 15. while another one showed a marginal association value (OR: 1.6)47 that apparently remained after a 30-year follow-up.49 Nevertheless, the association value could not be calculated nor was it reported by the researchers. Lack of occlusal stability (problems of intercuspation or posterior support) was consistently related to marginal association values, as well as to SSTMDs (OR: 1.7; 1.75;1.0; 1.5)10, 26, 27, 34 and ADs (OR: 1.2; 2.0).24, 28 On the other hand, CD > 2 mm and PC were consistently associated, although with marginal values, to SSTMD (OR: 1.9; 0.8; 0.25; 0.76; 1.1. RR: 2.2)14, 19, 21, 26, 31, 51, 52 and ADs (OR: 2.2; 1.2; 1.02).11, 16, 25 NSIs were inconsistently associated to SSTMDs; while some studies showed a strong association (OR: 2.18; 3.3; 8.72),9, 19, 49 other studies showed inverse (protective) association (OR: 0.6; 0.76; 0.5).14, 26, 31 Then again, canine and anterior guides were consistently shown with marginal association values and presence of SSTMDs (OR: 1.6;1.8; 1.1);15, 19, 31 however, group function was consistently presented as a factor of inverse (protective) association for SSTMDs (OR: 0.5; 0.5).15, 19 When the values related to occlusal adjustment were analyzed, it could be generally observed that many of the values reported were consistently presented as associated in an inverse manner (protective action) against SSTMDs (OR: 0.24; 0.12, RR: 0.6; 0.3; 0.124; 0.56; 0.58; 0.60),35, 37 although it should also be noted that a couple of exceptions a relation of association with stronger values (OR: 1.02; 2.68) was shown.35, 37Finally, OT was consistently related to marginal association values (OR: 1.6; 0,88; 1,0)38, 27, 46 and inverse (protective) association with SSTMDs (OR: 0,43; 0,16).39, 58, 59 Nevertheless, two of the studies presented OT as a risk factor for SSTMDs (OR: 3,2; 3,3).43, 61 Regarding DDs, OT was consistently associated by some reports in a neutral manner (OR: 1,0; 0,83; 1,0),40, 41, 45 while one study presented it as a risk factor with a not very strong—almost marginal—association value (OR: 2,0).44

- Temporal sequence of events.A long-term longitudinal study47, 48, 49 included crossbite, deep bite (VO > 4 mm) and forced centric displacement as OFs associated and previous to the emergence of SSTMDs. Similarly, the same study associated dental wear with the emergence of joint sounds (JS).48, 49 NSIs and PC/CD have also been associated as previous to the emergence of SSTMDs and RCTs in the short term.50, 51, 52 On the other hand, some RCTs have demonstrated that eradication of these interferences in a preventive manner reduces the necessity of treatment and the emergence of SSTMDs.53, 55 However, this was not the case in other strong associations such as open bite, HO > 4 mm, and CD > 2 mm to ADs, in which it seemed to be that the OFs were a consequence (they appeared after the disease) and not the cause of the disease.13, 17

- Dose-response relation.In general, reports specifically approaching this topic were not found. John (2002)30 analyzed different levels of attrition; nevertheless, they did not report association with the severity, frequency or duration of the SSTMDs. None of the articles evaluated in this literature review presented a gradient relation in terms of increase or worsening of either the SSTMDs or the diagnostics sub-groups in relation to the OFs’ increase, Size of worsening.

- Biological credibility. In spite of the various associations reported by different authors, their biological mechanisms are not fully understood.64-67 De Boever (1994)67 summarized the diverse etiological and physiopathological mechanisms in five general groups: The mechanic displacement, neuromuscular, muscular, and psychophysiological theories, as well as the psychological theory. It is important to point out that all of these theories have limitations in the light of scientific evidence; therefore, the discussion on the etiology of TMDs is not over yet, and several theories still exist.64-67 A single-cause relationship between OFs and TMDs is increasingly more difficult to consider because a great number of factors besides the OFs are also associated to TMDs (sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, among others), especially when the TMD becomes a chronic disorder.64-67 Although the etiology of acute joint or muscle pain is usually clear and is explained by history of trauma in the orofacial region or by inflammatory processes of the TMJ, in many other TMDs these mechanical factors are no frequently found. In turn, other authors, with the intention of not leaving factors behind, have suggested the multifactorial theory, and although in biology practically everything is multifactorial and shows the complexity of the mechanisms associated to the TMDs, this does not necessarily facilitate achievement of a deeper understanding of the biological mechanism.67-68 As the previously described theories have failed to explain the etiology of DTMs, other authors have suggested that their etiology is idiopathic (diseases with an unknown origin or whose cause is unknown).69-71 Currently, there is not an accepted biological mechanism and the scientific tendency is to search for a biological mechanism in possible disorders of the central and peripheral nervous system that would predispose patients to the development of TMD.72-74 Genetic aspects associated to this possible predisposition to produce pain have been reported in the last decade.75-78

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological concepts to establish causality are used and applied in research in order to make the best possible clinical recommendations or to perform public health actions. A classic example is the change of policies regarding smoking areas in order to decrease the risk for passive smokers, as well as the clinical recommendation, aimed at the general public, about the importance of quitting smoking.

All this happened after many years of research that verified the causal association between the habit of smoking and the development of many diseases (cancer, cardiovascular diseases). Epidemiology is a field full of uncertainties, in which in rare occasions the available evidence is enough to unmistakably establish the presence of a cause-effect relationship. This is especially true in the case of chronic diseases, for which strong epidemiological bases to find a cause-effect relationship are usually missing; therefore, in many occasions, depending on the risk or the associated consequences, it is wiser to act under the premise that the relationship exists instead of waiting for new evidence. Indeed, many years usually pass before having enough evidence that leads to decision making based on judgments that are far from having a reasonable doubt of a cause-effect relationship. In their book, Lilienfeld and Stolley (1994)8 wrote: “In practice, a relationship is considered causal provided that the evidence indicates that the factors make part of the set of circumstances that increase the possibility of developing disease, and that decreasing one or more of these factors also decreases the frequency of the disease”. They also wrote: “The etiological factor doesn’t have to be the only cause of the disease, and it could have effects in other diseases”.8 These might be the same reasons why currently the cause-effect relationship between OFs and TMDs is still controversial and is still studied and analyzed. The complete and extensive review presented in this series of publications 1- 5 is a response about being aware of the fact that establishing causality in epidemiology is not an exact activity and it depends on the evaluation of all available evidence according to the criteria for establishing causality (table 1). Although none of these criteria alone may validate causality, the greater number of criteria the greater possibility of a valid causal relationship.

When evaluating the strength of association between OFs and TMDs, the relationship is clear for some of the OFs [open bite (OA = 8,2); HO > 4 mm (OA = 5,0); VO > 4 mm (OA = 4,6); crossbite (OA = 3,87)]; marginal for some others [dental attrition (OA = 2,3) occlusal stability (OA = 2,0) NSI (OA = 1,9), premature contacts/CD (OA = 1,7); Class II (OA = 1,67); lack of canine guide (OA = 1,3); midline discrepancies (OA = 1,2)]; and yet inverse (protective) for other few cases such as the presence of group function (OA = 0,62). Occlusal adjustment presented marginal values with a preventive tendency against SSTMDs (OA = 0,74), while OT presented a similar situation but with a slight tendency to being a risk factor (OA = 1,2). Nevertheless, several other factors weaken the possible causal relationship between OFs and TMDs. It should be noted that, in spite of presenting these associations, not all of the OFs are associated in the same way, with the same disorders or the same strength. Similarly, when evaluating the consistency of the diverse findings, it may be observed that a clear tendency is not necessarily present in the directionality of the association and, in some cases, totally opposed values are noticed. A common situation is also observed, as being contrary to support the criterion of consistency: many of the reported association values were consistent in the same group of researchers and have not been repeated by other research groups. In California (USA), Pullinger et al proved10 a strong relationship between open bite and myalgia (OR: 6,0), while in Italy, Landi et al proved32 the opposite association in relation to another muscular disorder, DMF (OR: 0,8). The preventive effect of occlusal adjustment has been proved only by the Finn group of Kirveskari et al,53, 54, 55 but no other groups have shown similar results. Nevertheless, the findings reported by Kirveskari et al55 should not be minimized, as by means of a double blind RCT they demonstrated that removal of occlusal interferences (including premature contacts and NSI) by means of occlusal adjustment with selective grinding did not only have a preventive effect against the occurrence of SSTMDs, but it also decreased the need of treatment. Similarly, there is one single investigation, carried out by the same group, which reported the therapeutic effect of occlusal adjustment in other orofacial pain conditions commonly connected to TMDs (cephalalgia and cervical pain).57 A similar situation occurs with the reports on treatment of occlusal conditions with OT, which have demonstrated that it could reduce the need of TMD treatment.59, 60

However, the strength of this association is not high, nor has it been repeated by other studies so that the concept of consistency could be supported. Moreover, many of these associations were generated by CCS studies, which do not allow confidently establishing the temporal sequence of events; as mentioned, this can only be achieved by means of (LS and RCT) studies that allow monitoring the behavior of the risk factors and the disease over time. The only long-term longitudinal study with a 30-year follow-up maintained the association between deep bite, crossbite, CD and the occurrence of SSTMDs.48, 49 The same study also proved association between dental wear and joint sounds (JS) in the TMJ.38 Similarly, in a short-term (two weeks) RCT, premature contacts and the NSI maintained the relationship as a risk factor for the occurrence of SSTMDs.50-52 Nevertheless, none of the studies previously mentioned reported some kind of association between the OFs and the development of a diagnostic sub-group specific of TMD, nor the development of a condition similar to the one presented in patients who consult specialized clinics for treatment of TMDs and orofacial pain, or maybe, on the contrary, those SS were more similar to the SSTMD found among the general population. Regarding dose-response relation, the information provided by the articles evaluated in this review cannot support this concept. Intensity, frequency and duration of the OFs have not been associated to the worsening or accentuation of TMDs. For example, none of the EOI3 investigations reported stronger association to the appearance or worsening of SS due to a greater size of the interference. Association between “size” of the OF and severity of the TMD was not reported either. For example, crossbite has been associated to the SSTMDs, but it has not been proved whether the level of severity is correlated to the quantity of SS, or if these SS are more frequent, constant or intense in presence of a more pronounced crossbite. On the other hand, open bite is associated to arthritic disorders (ADs) and, if the severity of ADs were defined in terms of destruction of joint tissues, it could be assumed that the severity of open bite is greater as far as osteoarthrosis, osteoarthritis, or polyarthritis of the TMJ are more severe. Nevertheless, this causal association cannot be supported because the temporal sequence of events is different (open bite is caused or happens after the AD), and the biological mechanism of ADs does not lead to believe that open bites increase the risk of developing this disease. Finally, in the biological mechanisms of the masticatory system, it is reasonable to believe that sudden changes in the OFs may generate or explain the presence of acute SSTMDs (of temporal occurrence), such as mandibular pain.3, 79 Nevertheless, in chronic TDM conditions, relying on the primary participation of OFs in the development of these disorders is something difficult to maintain.72-74 In a recent study, Aggarwal et al80 showed that, even though there existed an independent relationship between mechanical factors (report of dental cracking, facial trauma, uncomfortable bite, lack of teeth) and chronic facial pain, this relation was altered by psychological factors which functioned as variables of confusion. Besides, these mechanical factors were also common in other idiopathic conditions of chronic pain.80 Apparently, these idiopathic conditions of chronic pain, including TMDs, coexist in the same patients and share a similar biological mechanism.81, 82 Finally, it is also very interesting to point out that the only longitudinal study in which OT was reported as a risk factor for TMD was the one that considered genetic aspects as predisposition to generate pain.61 This represents a highly important issue since, although the general tendency of the epidemiological reports analyzed in this article indicate that the tendency to favor the relationship between OFs and TMDs is inexistent, these other (genetic) factors may be the ones actually participating as variables of confusion and therefore leading to confusing, unclear results that interfere with the establishment of the real association between OFs and TMDs.75-78 All of these factors (either genetic or psychosocial) should be more closely considered and monitored in future studies seeking evaluation of causal relationships between OFs and TMDs.

CONCLUSIONS

The role of OFs in the etiology of TMDs is undoubtedly controversial and therefore the possible relationship between OFs and TMDs is not easy to analyze or interpret. The purpose of this extensive literature review was to evaluate in a detailed and complete manner the possible causal relationship between OFs and TMDs. In order to assure the generation of a centered and clear conclusion about this possible relationship, the main epidemiological principles for the evaluation of causality were used. When the strength of association between OFs and TMDs was evaluated, it was evident that several OFs had strong association values, which turned them into risk factors for the development of TMDs. It should be noted that, in spite of presenting these associations, not all of the OFs are associated in the same way, with the same disorders or the same strength. Similarly, when evaluating the consistency of the diverse investigations’ findings, it may be observed that a clear tendency is not necessarily present in the directionality of the association and, in some cases, totally opposed values are noticed. A common situation is also observed, as being contrary to support the criterion of consistency: many of the reported association values were consistent in the same group of researchers and have not been repeated by other research groups. Moreover, many of these association values were generated by CCS studies, which do not allow confidently establishing the temporal sequence of events, and although some LSs and RCTs maintained the association of some of the OFs with the apparition of SSTMDs, none of the studies previously mentioned reported some kind of association between the OFs and the development of a diagnostic subgroup specific of TMD, nor the development of a condition similar to the one presented in patients who consult specialized clinics for treatment of TMDs and orofacial pain, or maybe, on the contrary, those SS were more similar to the SSTMDs found among the general population. Regarding the dose-response relation, the information provided by the articles evaluated in this review cannot either be supported because intensity, frequency, and duration of the OFs were not associated to the worsening or accentuation of the TMDs. Finally, in the biological mechanisms of the masticatory system, it is reasonable to believe that mechanical changes (direct or indirect trauma, or sudden changes in the OFs) may generate or explain the presence of acute SSTMD (of temporal occurrence), such as mandibular pain. Nevertheless, relying on the primary participation of OFs in the development of chronic TMDs is something difficult to maintain, and it looks more like the modest peripheral participation of a multifactorial collection of causes. Therefore, with the scientific information currently available, the causal relationship between OFs and TMDs is weak and confusing, and several recommendations may then be made:

- Future research projects should try to make more emphasis on the analysis of associations between OFs and diagnostics sub-groups of TMDs (instead of just observing in the simple presence or absence of SSTMDs), having into account other factors such as chronicity and treatment need, and considering other comorbid factors that may appear as variables of confusion (systemic, genetic or bio-psycho-social aspects such as depression, anxiety, or sleep disorders, among others).

- More multi-centric LSs and RCTs are needed in order to produce association values that may also be supported by the concepts of consistency and temporal sequence of events.

- The studies must be carried out using clinical evaluation methods and standardized diagnostics in order to establish the health/disease state, so that comparisons among different studies may be more easily made.

- Researchers must consider the production of association values or present data in an organized manner following the principles of evidence-based practice so that the values may be easily and clearly calculated.

- Because the causal relationship between OFs (including occlusal adjustment and OT) and TMDs is weak and confusing, one must be cautious, adhering to the principle of being simple and conservative at the time of establishing a therapeutic strategy, and avoiding treatments that lead to irreversible occlusal changes, only supported by the conviction that a decisive impact in the SSTMDs is being produced in patients.

- The possible occurrence of SSTMDs in some patients while others do not suffer them after experiencing occlusal changes may be due to individual genetic predisposition instead of the mechanical effect that such occlusal changes imply. Possibly in the future it will be necessary to perform blood tests in order to make a gene mapping and thus establish the patients’ individual risk of developing SSTMDs.

1.Acosta-Ortiz R, Rojas BP. Una revisión de la literatura sobre la relación causal entre los factores oclusales (FO) y los desórdenes temporomandibulares (DTM) I: estudios epidemiológicos descriptivos. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2006: 17(2): 67-85. [ Links ]

2.Acosta-Ortiz R, Rojas BP. Una revisión de la literatura sobre la relación causal entre los factores oclusales (FO) y los desórdenes temporomandibulares (DTM) II: estudios epidemiológicos analíticos de observación. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2006; 18(1): 55-67. [ Links ]

3. Acosta-Ortiz R, Roura N. Una revisión de la literatura sobre la relación causal entre los factores oclusales (FO) y los desórdenes temporomandibulares (DTM) III: estudios experimentales con interferencias oclusales (IO) artificiales. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2008; 20(1): 87-96. [ Links ]

4. Acosta R, Roura N. Una revisión de la literatura sobre la relación causal entre los factores oclusales (FO) y los desórdenes temporomandibulares (DTM) IV: estudios experimentales del ajuste oclusal por tallado selectivo como intervención preventiva ó terapéutica. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 21: 98-111. [ Links ]

5. Acosta R, Rojas BP. Una revisión de la literatura sobre la relación causal entre los factores oclusales (FO) y los desórdenes temporomandibulares (DTM) V: efecto de los cambios en los factores oclusales conseguidos con el tratamiento de ortodoncia. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2011; 22(2): 205-226. [ Links ]

6. Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston: Mayrent SL: Philadelphia: 1987. [ Links ]

7. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology. 3.ª ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [ Links ]

8. Lilienfeld DE, Stolley PD. Foundations of epidemiology. 3.ª ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [ Links ]

9. Geering AH. Occlusal interferences and functional disturbances of the masticatory system. J Clin Periodontol 1974; 1: 112-119. [ Links ]

10. Pullinger AG, Xu Y, Solberg WK. Relationship of occlusal stability to masticatory disorders. J Dent Res 1984; 55: 498. [ Links ]

11. Seligman DA, Pullinger AG, Association of occlusal variables among refined TM patients diagnostic groups. J Craniomandib Disord Facial Oral Pain 1989; 3: 227-236. [ Links ]

12. Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L et al. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc 1990; 120: 273-281. [ Links ]

13. Pullinger AG, Seligman DA. Overbite and overjet characteristics of refined diagnostic groups of temporomandibular patients. AmJ Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1991; 100: 401-415. [ Links ]

14. Steele JG, Lamey PJ. Sharkey SW. Smith GM. Occlusal abnormalities, pericranial muscle and joint tenderness and tooth wear in a group of migraine patients. J Oral Rehabil 1991; 18: 453-458. [ Links ]

15. Cacchiotti DA, Plesh O, Bianchi P, McNeill C. Signs and symptoms in sample with and without temporomandibular disorders. J Craniomandib Disord Facial Oral Pain 1991; 5: 167-172. [ Links ]

16. Kononen M, Wenneberg B, Kallenberg A. Craniomandibular disorders in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. A clinical study. Acta Odontol Scand 1992; 50: 281-287. [ Links ]

17. Pullinger AG, Seligman DA, Gornbein JA. A multiple logistic regression analysis of the risk and relative odds of temporomandibular disorders as a function of common occlusal features. J Dent Res 1993; 72: 968-979. [ Links ]

18. Seligman D, Pullinger A. A multiple stepwise logistic regression analysis of trauma history and 16 other history and dental cofactors in females with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 1996; 10: 351-361. [ Links ]

19. Tsolka P, Fenlon MR, McCullock AJ, Preiskel HW. A controlled clinical, electromyographic, and kinesiographic assessment of craniomandibular disorders in women. J Orofac Pain 1994; 8: 80-89. [ Links ]

20. Tsolka P, Walter JD, Wilson RF, Preiskel HW. Occlusal variables, bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: a clinical and kinesiographic assessment. J Oral Rehabil 1995; 22: 849-856. [ Links ]

21. Raustia AM, Pirttiniemi PM, Pyhtinen J. Correlation of occlusal factors and condyle position asymmetry with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in young adults. J Craniomandib Pract 1995; 13: 152-156. [ Links ]

22. Kahn J, Tallents RH, Katzberg RW, Moss ME, Murphy WC. Association between dental occlusal variables and intraarticular temporomandibular joint disorders: horizontal and vertical overlap. J Prosthet Dent 1998; 79: 658-662. [ Links ]

23. Kahn J, Tallents RH, Katzberg RW, Moss ME, Murphy WC. Prevalence of dental occlusal variables and intraarticular temporomandibular disorders: Molar relationship, lateral guidance, and nonworking side contacts. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82: 410-415. [ Links ]

24. Pullinger AG, Seligman DA. Quantification and validation of predictive values of occlusal variables in temporomandibular disorders using a multifactorial analysis. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 83: 66-75. [ Links ]

25. Seligman DA, Pullinger AG. Analysis of occlusal variables, dental attrition, and age for distinguishing healthy controls from females patients with intracapsular temporomandibular disorders. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 83: 76-82. [ Links ]

26. List T, Wahlund K, Larsson B. Psychosocial functioning and dental factors in adolescents with temporomandibular disorders: A case-control study. J Orofac Pain 2001; 15: 218-227. [ Links ]

27. Macfarlane TV, Gray RJM, Kincey J, Worthington HV. Factors associated with the temporomandibular disorder, pain dysfunction syndrome (PDS): Manchester case-control study. Oral Dis 2001; 7: 321-330. [ Links ]

28. Yamakawa M, Ansai T, Kasai S, Ohmaru T, Takeuchi H, Kawaguchi T et al. Dentition status and temporomandibular joint disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Cranioamdib Pract 2002; 20: 165-170. [ Links ]

29. Tallents RH, Macher DJ, Kyrkanides S, Katzberg RW, Moss ME. Prevalence of missing posterior teeth and intraarticular temporomandibular disorders. J Prosthet Dent 2002; 87: 45-50. [ Links ]

30. John MT, Frank H, Lobbezzo F, Drangsholt M, Dette KE. No association between incisal wear and temporomandibular disorders. J Prosthet Dent 2002; 87: 197-203. [ Links ]

31. Fujii T. Occlusal conditions just after the relief of temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscle pain. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29: 323-329. [ Links ]

32. Landi N, Manfredini D, Tognini F, Romagnoli M, Bosco M. Quantification of the relative risk of multiple occlusal variables for muscle disorders of the stomatognathic system. J Prosthet Dent 2004; 92: 190-195. [ Links ]

33. Selaimen CM, Jeronymo JC, Brilhante DP, Lima EM, Grossi PK, Grossi ML. Occlusal risk factors for temporomandibular disorders. Angle Orthod. 2007; 77: 471-477. [ Links ]

34. Takayama Y, Miura E, Yuasa M, Kobayashi K, Hosoi T. Comparison of occlusal condition and prevalence of bone change in the condyle of patients with and without temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 105: 104-112. [ Links ]

35. Kirveskari P, Alanen P, Jämsä T. Association between cranio-mandibular disorders and occlusal interferences. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 62: 66-69. [ Links ]

36. Vallon D, Ekberg EC, Nilner M, Kopp S. Short-term effect of occlusal adjustment on craniomandibular disorders including headaches. Acta Odontol Scand 1991; 49: 89-96. [ Links ]

37. Vallon D, Ekberg EC, Nilner M, Kopp S. Occlusal adjustment in patients with craniomandibular disorders including headaches. A 3 and 6 months follow-up. Acta Odontol Scand 1995; 53: 55-59. [ Links ]

38. Pullinger AG. Monteiro AA. History factors associated with symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil 1998; 15(2): 117-124. [ Links ]

39. Egermark I, Thilander B. Craniomandibular disorders with special reference to orthodontic treatment: an evaluation from childhood to adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1992; 101: 28-34. [ Links ]

40. Katzberg RW, Westesson PL, Tallents RH, Drake CM. Orthodontics and tem oromandibuler joint internal derangment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996; 109: 515-520. [ Links ]

41. Tallents RH, Katzberg RW, Murphy W, Proskin H. Magnetic resonance imaging finding in asymptomatic volunteers and symptomatic patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Prosthet Dent 1996; 75: 529-533. [ Links ]

42. Huang Gj, LeResche L, Critchlow, Martin MD, Drangsholt MT. Risk factors for diagnostic subgroups of painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD). J Dent Res 2002; 81: 284-288. [ Links ]

43. Velly AM, Gornitsky M, Philippe P. A case-control study of temporomandibular disorders: symptomactic disc displacement. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29: 408-416. [ Links ]

44. Velly AM, Gornitsky M, Philippe P. Heterogenecity of temporomandibular disorders: cluster and case-control study analyises. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29: 969-979. [ Links ]

45. Mohlin BO, Derweduwen K, Pilley R, Kingdon A, Shaw WC, Kenealy P. Malocclusion and temporomandibular disorder: A comparison of adolecents with moderate to severe dysfunction with those without signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and their futher development to 30 years of age. Angle Orthod 2004; 74: 319-327. [ Links ]

46. Macfarlane TV, Kenealy P, Kingdon HA, Mohlin BO, Pilley JR, Richmond S et al. Twenty-year cohort study of health gain from orthodontic treatment: temporomandibular disorders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 135: 692. e1-692.e8. [ Links ]

47. Egermark-Eriksson I, Carlsson GE, Magnusson T, Thilander B. A longitudinal study on malocclusion in relation to signs and symptoms of craniomandibular disorders in children and adolescents. Eur J Orthod 1990; 12: 399-407. [ Links ]

48. Carlsson GE, Egermark I, Magnusson T. Predictors of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders: a 20-year follow-up study from childhood to adulthood. Acta Odontol Scand 2002; 60: 180-185. [ Links ]

49. Magnusson T, Egermarki I, Carlsson GE. A prospective investigation over two decades on signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and associated variables. A final summary. Acta Odontol Scand 2005; 63(2): 99-109. [ Links ]

50. Magnusson T, Enbom L. Signs and symptoms of mandibular dysfunction after introduction of experimental balancingside interferences. Acta Odontol Scand 1984; 42: 129-135. [ Links ]

51. Le Bell Y, Jamsa T, Korri S, Niemi PM, Alanen P. Effect of artificial occlusal interferences depends on previous experience of temporomandibular disorders. Acta Odontol Scand 2002; 60: 219-222. [ Links ]

52. Le Bell Y, Jamsa T, Korri S, Niemi PM, Alanen P. Effect of artificial occlusal interferences depends on previous experience of temporomandibular disorders. Acta Odontol Scand 2006; 64: 59-63. [ Links ]

53. Kirveskari P, Le Bell Y, Salonen M, Forssell H, Grans L. The effect of the elimination of occlusal interferences on signs and symptoms of craniomandibular disorders in young adults. J Oral Rehabil 1989; 16: 21-26. [ Links ]

54. Karjalainen M, Le Bell Y, Jämsä T, Kayalainen S. Prevention of temporomandibular disorder related signs and symptoms in orthodontically treated adolescents. A 3 year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Acta Odontol Scand 1997; 55: 319-324. [ Links ]

55. Kirveskari P, Jämsä T, Alanen P. Occlusal adjustment and the incidence of demand for temporomandibular disorder treatment. J Prosthet Dent 1998; 79: 433-438. [ Links ]

56. Tsolka P, Marvis PW, Preiskel HW. Occlusal adjustment therapy for craniomandibular disorders: a clinical assessment by a double blind method. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 68: 957- 964. [ Links ]

57. Karppinen K, Eklund S, Souninen E, Eskelin M, Kirveskari P. Adjustment of dental occlusion in treatment of chronic cervicobrachial pain and headache. J Oral Rehabil 1999; 26: 715-721. [ Links ]

58. Henrikson T, Nilner M. Temporomandibular disorders and the need for stomatognathic treatment in orthodontically treated and untreated girls. Eur J Orthod 2000; 22: 283-292. [ Links ]

59. Henrikson T, Nilner M, Kurol J. Signs of temporomandibular disorders in girls receiving orthodontic treatment: a prospective and longitudinal comparison with untreated Class II malocclusions and normal occlusion subjects. Eur J Orthod 2000; 22: 271-281. [ Links ]

60. Henrikson T, Nilner M. Temporomandibular disorders, occlusion and orthodontic treatment. J Orthod 2003; 30: 129-137. [ Links ]

61. Slade GD, Diatchenko L, Orbach R, Maixner W. Orthodontic treatment, genetic factors, and risk of temporomandibular disorders. Semin Orthod 2008; 14: 146-156. [ Links ]

62. Egermark I, Magnusson T, Carlsson GE. A prospective study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in patients who received orthodontic treatment in childhood. Angle Orthod 2003; 75: 645-650. [ Links ]

63. Egermark I, Magnusson T, Carlsson GE. A 20-year followup of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and malocclusion in subjects with and without orthodontic treatment in childhood. Angle Orthod 2003; 73: 109-115. [ Links ]

64. Mohlin C. From bite to mind: TMD a personal and literature review. Inter J Prosthod 1999; 12: 279-288. [ Links ]

65. Green CS. Concepts of TMD etiology: effects on diagnosis and treatment. En: Laskin DM, Greene CS, Hylander WL. Temporomandibular Disorders. An evidence-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. Chicago: Quintessence Pubblishing, 2006. [ Links ]

66. Sessle BJ. Lavigne GJ, Lund JP, Dubner R. Orofacial pain. From basic science to clinical management. 2.ª ed. Chicago: Quintessence Pubblishing, 2008. [ Links ]

67. De Boever JA, Carlsson GE. Etiology and differential diagnosis. En: Zarb GA, Carlsson GE, Sessle BJ, Mohl ND, eds. Temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscle disorders. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1994. [ Links ]

68. Parker MW. A dynamic model of etiology in temporomandibular disorders. J Am Dent Assoc 1990; 120: 283-290. [ Links ]

69. Woda A, Pionchon P. A unified concept of idiopathic orofacial pain: clinical features. J Orofac Pain 1999; 13: 172-184. [ Links ]

70. Woda A, Pionchon P. A unified concept of idiopathic orofacial pain: pathophysiologic features. J Orofac Pain 2000; 14: 196-212. [ Links ]

71. Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Lunt M, Zakrzewska JM, Macfarlane GJ. Development and validation of classification criteria for idiopathic orofacial pain for use in populationbased studies. J Orofac Pain 2007; 21: 203-215. [ Links ]

72. Svensson P, Arendt-Nielson L. Clinical and experimental aspects of temporomandibular disorders. Current Review of Pain 2000; 4: 158-165. [ Links ]

73. Greene CS, Laskin DM. Temporomandibular disorders: moving from a dentally based to a medically based model. J Dent Res 2000; 7910: 1736-1739. [ Links ]

74. Suvinen TI, Reade PC, Kemppainen P, Kononen M, Dworkin SF. Review of aetiological concepts of temporomandibular pain disorders: towards a biopsychosocial model for integration of physical disorder factors with psychological and psychosocial illness impact factors. Eur J Pain 2005; 96: 613-633. [ Links ]

75. Oakley M. Vieira AR. The many faces of the genetics contribution to temporomandibular joint disorder. Orthod Craniofacial Res 2008; 11: 125-135. [ Links ]

76. Fillingim RB, Wallace MR, Herbstman DM, Ribeiro- Dasilva M. Staud R. Genetic contributions to pain: a review of findings in humans. Oral Diseases 2008; 14: 673-682. [ Links ]

77. Stohler CS. A genetic vulnerability disorder with strong CNS involvement. J Evid Base Dent Pract 2006; 6: 53-57. [ Links ]

78. Diatchenko L, Salde GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I et al. Genetic basis for individual variation in pain perception and the development of chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet 2005; 14: 135-143. [ Links ]

79. Clark GT, Tsukiyama Y, Baba K, Watanabe T. Sixty-eight years of experimental occlusal interference studies: what have we learned? J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82: 704-713. [ Links ]

80. Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Zakrzewska JM, Lunt M, Macfarlane GJ. Are reports of mechanical dysfunction in chronic oro-facial pain related to somatisation? A population based study. Eur J Pain 2008; 12: 501-507. [ Links ]

81. Schur EA, Afari N, Furberg H, Olarte M, Goldberg J, Sullivan PF et al. Feeling bad in more ways than one: comorbidity patterns of medically unexplained and psychiatric conditions. J Gen Inter Med 2007; 22; 6: 818-821. [ Links ]

82. Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Zakrzewska JM, Lunt M, Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have common associated factors? Inter J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 468-476. [ Links ]

text in

text in