Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.2 Medellín Jan./June 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

Effects of LED/laser on the enamel due to exposure during dental bleaching

Andrea Katerine Durán1; Ángela Cristina Lucumí1; Lina María Zapata1; Henry Correa2; Herney Garzón3

1 Odontólogas, Universidad del Valle. Cali, Colombia

2 Odontólogo, especialista en Ortodoncia. Práctica privada

3 Odontólogo, especialista en Rehabilitación Oral, docente Escuela de

Odontología Universidad del Valle. Cali, Colombia

SUBMITTED: AUGUST 16/2011 - ACCEPTED: DECEMBER 13/2011

Durán AK, Lucumí ÁC, Zapata LM, Correa H, Garzón H. Effects of LED/laser on the enamel due to exposure during dental bleaching. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 23(2): 256-267.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the objective of this study was to identify the clinical and morphological laser effects on human vital teeth

during dental bleaching procedures.

METHODS: this experimental study included 11 patients ages 21 to 35, from whom 22 healthy premolar

teeth, with no restorations, fractures or crown defects were collected. These premolar teeth were extracted because of orthodontic reasons.

The effects of performing dental bleaching with GC TiON® (GC dental, Washington, USA), and with and without LED/Laser Ultrablue IV

(DMC Equipments Sao Paulo, Brasil) were compared. The teeth were divided into three groups: control group (n = 2), group 1 (n = 10),

using GC TiON® with laser, and group 2 (n = 10), using GC TiON® without laser. After extraction, the teeth were conserved in distilled

water. Color monitoring was performed before and after each whitening session. Alterations on the buccal surface of the samples were

analyzed by means of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

RESULTS: 85% of the teeth (17) did not show enamel alterations, 10% (2 teeth)

presented mild alterations, and only 5% (1 tooth) suffered moderate enamel alterations. No significant color change difference occurred

among the groups; out of the 20 samples, 6 of them reached tone B1 in the first session, 7 in the second session, and 7 more in the third one.

CONCLUSIONS: Scanning Electron Microscopy did not reveal severe damage in dental structure. No significant difference in teeth whitening

level occurred.

Key words: dental laser, dental bleaching, hydrogen peroxide.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, a great variety of products for dental bleaching is available to dentists who seek to improve their patients' dental aesthetics,1, 2 arising great interest not only among the scientific community but also in general population.3, 4

The abundant requests for these esthetic procedures is due to the presence of chromatic dental alterations which may be either intrinsic (pulpitis, iatrogenesis, enamel hypoplasia, imperfect dentinogenesis, erytrhroblstosis fetalis, fluorosis) or extrinsic, due to the formation and deposit of pigmented substances in the dental structure surface.4-7

These conditions have led dentists to try to recover the morphological characteristics of their patients' dental structure (a natural clear tone of the teeth) by means of dental bleaching procedures with and without laser; nevertheless, there is some possibility of these procedures causing unwanted side effects.8-14

With the arrival of new dental bleaching techniques, a great amount of products including laser15 have emerged, which have revealed, by means of scientific studies, changes in the dental structure components such as enamel, dentine and pulp.2, 7, 13, 16 Although it has been proved that most whitening products can efficiently achieve chromatic changes, some studies show no change or whitening effect in dental structure.1, 17, 18

As this is such a highly interesting issue and a frequent reason of consultation, dental professionals rely on different alternatives and make use of the various techniques and clinical protocols available that include temporal changes or the use of accelerators such as laser.19

The purpose of this study is to better understand the effects of a source (hybrid LED/laser) during an in-office dental bleaching treatment and to assess whether the laser source has a harmful effect on enamel or not.

METHODS

Sample collection

Ten patients and one control patient, aged 21 to 35 years, were recruited after having their informed written consent, thus complying with current regulations (Resolution 8430, Ministerio de Salud de Colombia, 1993), and with the approval of the Institution's Ethics Committee. Two healthy upper or lower premolars from each subject were selected. The extractions were performed by a maxillofacial surgeon who used a standardized protocol in order to preserve the teeth's buccal side and not to alter the study's results. The samples were preserved in distilled water, which was renewed every five days during two months.

For allocation of the samples in each group, they were numbered and distributed by means of a table of random numbers as follows:

Group 1 (bleaching-LED/laser): 10 teeth.

Group 2 (bleaching without LED/laser): 10 teeth.

Control group: No bleaching: 2 teeth.

Bleaching protocol

Before the bleaching procedure, the initial shade of each tooth was graded according to the classic VITA scale guide.

Prophylaxis was performed with Profiflex 3-2018® (prophylaxis paste without fluoride) in groups 1 and 2.

Group 1 was treated with GC TiON® in office whitening (GC dental, Washington, USA), composed by 30% hydrogen peroxide + 30% carbamide peroxide, with a 2:30 min LED Laser Ultrablue IV (DMC Equipamientos São Paulo, Brasil) exposure time, 830 nm wavelength for the laser diode, and 470 nm for the LED at 190 mW/cm2 (figure 1).

Group 2 was treated with the same bleaching system but without exposure to LED/Laser, with an application time of 30 min, meticulously following the protocol by the dental house (Gc America).

Once the bleaching process was completed, the teeth's final shade was registered for later analysis of results.

Sample analysis

The total number of samples (n = 22) were analyzed by means of scanning electron microscopy.

After bleaching, the samples were stored in distilled water inside a thermic recipient at a temperature of 37 °C, and then sections were obtained with a low speed disc Isomet microtome. Sections of approximately 2 mm of thickness were made in a coronal-apical direction right by the cusp edge so that each tooth was sectioned in its distal and mesial sides.6, 10, 13, 14, 16

They were individually stored in hermetic seal bags. Afterwards, sample analyses were made by scanning electron microscope, and images of 2.000 and 3.000 X magnification were obtained for each tooth.

RESULTS

Microscopic findings

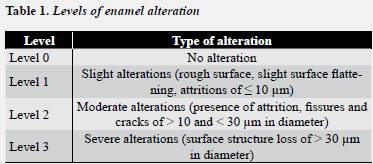

Images were analyzed from the buccal enamel zone closest to each sample's section in order to verify the presence or absence of enamel defects, according to the parameters shown in table 1.20

The evaluator was an adamantine morphologic evaluation expert and was not aware of the experiment's objectives (simple masking).

Analysis of the electron microscopy results allowed concluding that the teeth subjected to dental bleaching with laser presented different effects on their enamel surface.

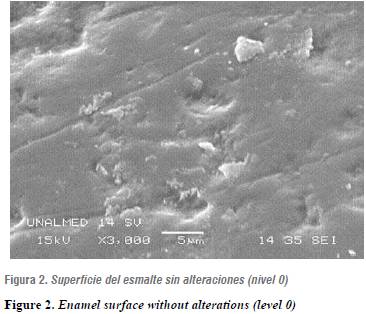

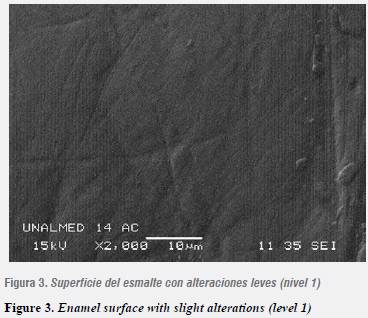

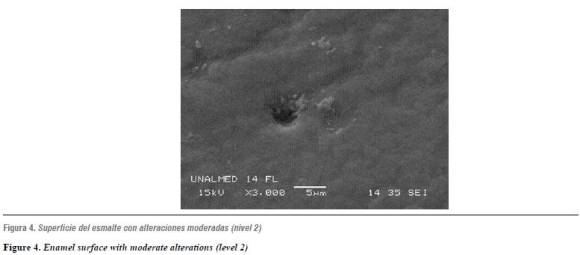

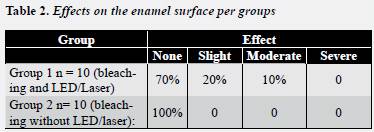

None of the teeth of the group treated for dental bleaching with laser (group 1) presented severe enamel alterations. 70% (seven teeth) showed no enamel alterations or damage (figure 2); 20% (two teeth) presented slight enamel alteration (figure 3), and 10% (one tooth) suffered moderate enamel alteration (figure 4). 100% of the teeth treated for dental bleaching without laser (group 2) showed no enamel surface alterations.

Out of all the samples analyzed (groups 1 and 2), 85% (seventeen teeth) showed no enamel alteration, 10% (two teeth) presented slight alterations, and only 5% (1 tooth) suffered moderate enamel alterations (table 2) .

Clinical findings

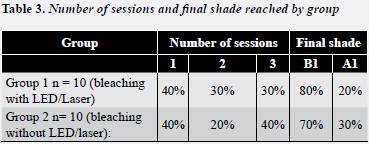

When dental bleaching level was registered after the first session, the following results were obtained (table 3)For group 1

In group 1, 80% of the teeth reached a final shade of B1; out of the teeth of group 2 (without LED/Laser), 70% reached B1 and 30% reached up to maximum shades of A1 and B2. 40% (4 teeth) reached B1 shade in the first session, and 30% (3 teeth) reached the same shade (B1) in the second session. And there was a 30% (3 teeth) that required a third session to reach shade B1.

For group 2

In group 2, just one session was needed for 40% of the total sample (4 teeth) to reach shade B1, 20% (2 teeth) required a second session to reach B1. And 40% (4 teeth) required three sessions to reach shade B1.

A second session was needed for 70% of the total sample (groups 1 and 2), corresponding to the premolars not yet reaching shade B1 (14 premolars), 28,57% (4 samples) suffered no shade changes, and 28,57% (4 samples) presented one shade of whitening. There were two cases (14,28%) that whitened between 3 and 4 shades. There were also two cases (14,28%) that whitened 2 shades. 50% of the sample reached shade B1 in the second session.

The third session was only needed for those premolars that had not reach shade B1. Three samples whitened 1 shade, one sample of group 1 whitened 4 shades, and three teeth maintained their original shade.

By applying the Mann-Whitney tests, a statistical analysis was performed, finding out that in one bleaching session without LED/Laser 33,3% of the patients reached one shade whiter, and that in one session with laser only 27,3% reached shade B1. In the second bleaching session without LED/ Laser, only 22,2% reached shade B1, while by using bleaching with laser 45,5% achieved the whitest shade. In the third session, all of the patients reached the whitest shade.

DISCUSSION

In diverse clinical situations, dentists must choose from several materials and equipment currently available in order to provide the patient with the best esthetic treatment, due to enormous esthetic social pressures, 19 that compel the dental professional to choose the best method to whiten teeth, according to the type of patient, in order to perform a successful treatment. 21, 22

Dental bleaching is not a relatively new technique,23 since as early as 1937 Ames reported a technique for the treatment of mottling enamel by using a mix of hydrogen peroxide and diethyl ether applied with cotton for 30 min in each session, during a period of 5 to 25 sessions.3 This has created great controversy about its effects on dental enamel, whitening level achieved in one session, and the presence of dental hypersensitivity7, 22, 24

There are several hypotheses about dental bleaching with laser decreasing more shades than at-home bleaching so that it requires fewer sessions and achieves a whiter shade in less time but causes greater enamel damage and much sensitivity compared to at-home bleaching.11, 25, 26

Clinical studies suggest that laser may be used without causing pulp lesions. Nevertheless, it has been generally assumed that any pulpal temperature increase over 5,5 °C is harmful.12, 27 But Eldeniz studied the pulpal temperature produced when applying two types of bleaching gel and exposing them to a conventional light for 40 s, a high intensity halogen lamp for 30 s, a LED unit for 40 s, and a diode laser for 15 s, finding out that the highest temperature increase occurred with the diode laser (11,7 °C), while the lowest one occurred with the LED unit (6 °C).9

Many studies agree that the main reason for choosing in-office dental bleaching is to lessen probable unwanted side effects compared to at-home bleaching, and also because it offers greater control by the patient, as it is done in a short and fast period of time.7, 13

On the other hand, this study suggests that no significant difference exists in dental whitening level between the in-office technique with laser and without it, since both procedures yielded the best clinical results in terms of enamel shade. Conversely, a study on dental bleaching published in 2008 by doctors Juan Carlos Pontons Melo and Guillermo Pontons concluded that electromagnetic radiation emitted by diode LED/Laser allows accelerating hydrogen peroxide decomposition, as well as the biomodulation effect, which reduces trans- and postreatment sensitivity.7 This would mean that by using LED/Laser during dental bleaching the number of sessions would be reduced and the level of sensitivity would be slight or even null.

Although no significant differences in dental bleaching occurred between the two techniques used in this study, we could observe that teeth subjected to bleaching with laser whiten somehow more quickly, satisfactorily achieving a final B1 shade, thus agreeing with the studies conducted by Tavares in 2003 and Araujo et al in 2010.28, 29

It is important to bear in mind that characteristics such as enamel, age, and magnitude of response are unique in each patient,24 and that there exist some teeth, like the ones used in this study, that even if subjected to several bleaching sessions do not satisfactorily reach shade B1. Concerning this last case, there is a study by doctors Marcelo Bertone and Silvia Zaiden, who in 2008 reported the case of a patient who was subjected to laser bleaching with LED/Laser and went from an A3.5 shade to an A2 shade in the VITA scale, decreasing 7 shades, by using 35% hydrogen peroxide, and considering that yellowish pigmentations are more susceptible of whitening than grayish ones.17

In 2004, Wetter et al11 compared the efficiency in vitro of a LED/Laser Easy Bleach lamp with to whitening agents, Whiteness HP and Opalescense® X-Tra, finding out that Opalescence® gel interacts better with LED/Laser. This happens in part due to carotene, a pigment contained in Opalescence® that has a better response to the LED source shortwave.11 This is why bleaching agents must be connected to the laser used, since few articles have been published on this field and therefore there are many aspects to be considered and researched in this field30-32 GC TiON for in-office use consists in the application and interaction of a dioxide-titanium-based (TiON) photocatalyzer and a bleaching gel with concentrations of H20 + H2O2 that are light-activated (LED/Laser Ultrablue IV) and produce dental bleaching five times more effective and safer than other products.

In this study, no significant differences were found in terms of the effects produced by dental bleaching with laser and without it on dental structure. In comparison with other articles that suggest that nearly 55 to 57% of patients experience dental sensitivity after bleaching, because of hydrogen peroxide and urea easily passing through the enamel and the dentine,33, 34

The effects on dental enamel revealed absence of alterations in the teeth in which bleaching was performed with laser; in terms of the teeth that were whitened with laser, only a small group presented slight and moderate enamel alterations.

It is important to perform a previous thorough examination of the enamel surface structure in order to find the explanation as to why some teeth, even if going through several bleaching sessions, regardless of the technique used, do not reach final shade (B1). Considering whether the stains are extrinsic or intrinsic, and that the shades are: recent, temporary, or permanent, it is worth noting that more recent stains are more susceptible of successful bleaching,35 while the ones that have been there for a longer time have a guarded prognosis.

CONCLUSIONS

Dental bleaching using GC TiON® without LED/ Laser exposure is very effective, as it only requires three sessions to reach the whitest shade, without producing enamel alterations, bearing in mind that the subjects of this study only presented extrinsic pigmentations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To doctors Adriana Jaramillo, Carlos Mejía, Julio Sendoya, Carlos Arturo Cruz; to Universidad Nacional at Medellín; to doctor Medardo Pérez, Doctor Jesús Hernández, and all the patients that participated in our study.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Herney Garzón

Calle 4B N.° 36-00 Edificio 132

Universidad del Valle, Sede San Fernando

Escuela de Odontología

Cali, Colombia.

Correos electrónicos:

Correos electrónicos: herney.garzon@correounivalle.edu.co

herneygarzon@hotmail.com

REFERENCES

1. Lai SCN, Tay Fr, Cheang GSP, Mak YF, Carvalho RM, Wey SHY et al. Reversal of compromised bonding in bleached enamel. J Dent Res 2002; 81(7): 477-481. [ Links ]

2. Li Y. Toxicological considerations of tooth bleaching using peroxide-containing agents. J Am Dent Assoc 1997; 128: 31S-36S. [ Links ]

3. Díaz A, Pérez L, Mattos M, Asurza J, Bernuy L. Niveles de erosión del esmalte dentario por efecto de agentes clareadores. Odont Sanmarquina 2009; 12(1): 3-5. [ Links ]

4. Maiman TH. Stimulated optical radiation in ruby. J Nature 1960; 187: 493-494. [ Links ]

5. Pick RM. Using lasers in clinical dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc 1993; 124(2): 37-34. [ Links ]

6. Miserendino LJ, Neiburger EJ, Walia H, Luebke N, Brantley W. Thermal effects of continuous wave CO2 laser exposure on human teeth: an in vitro study. J Endod 1989; 15(7): 302-305. [ Links ]

7. Pontons JC, Pontons G. Aclaramiento dental con fuentes hibridas LED/LASER. Rev ADM 2008; 65(3): 163-167. [ Links ]

8. Powell GL, Morton TH, Larsen AE. Pulpal response to irradiation of enamel with continuous wave CO2 laser. J Endod 1989; 15(12): 581-583. [ Links ]

9. Eldeniz AU, Usumez A, Usumez S, Ozturk N. Pulpal temperature rise during light activated bleaching. J Biomed Mater Res 2005; 72B(2): 254-259. [ Links ]

10. Cabrera A, David M, Pacheco LS, Suárez AC, Garzón H. Efectos del peróxido de hidrógeno activado con luz ultravioleta y el peróxido de carbamida en aclaramiento dental. Rev Estomatol 2008; 16(1):18-24. [ Links ]

11. Wetter UN, Barroso MC, Pelino JE. Dental bleaching efficacy with diode laser and LED irradiation in vitro study. Lasers Surg Med 2004; 35(4): 254-258. [ Links ]

12. Kegler E, Pinheiro PC, Batista E, Lia RF. Aumento de la temperatura intracámara pulpar durante el blanqueamiento con sistemas activados por luz. Revisión de la literatura. Acta Odontol Venez 2010; 48(3): 1-9. [ Links ]

13. Espina V, Larentis NL, Souza MA, Barbosa AN. Comparação da superfície do esmalte antes e após clareamento com dois diferentes agentes-estudo clínico. Stomatos 2008; 14(27): 44-52. [ Links ]

14. Miranda AM, Nima G, Bazán JE, Saravia M. Efectos de un blanqueamiento dental con ozono y otro con peróxido de carbamida al 22% sobre la fuerza de adhesión al esmalte en diferentes intervalos de tiempo. Acta Odontol Venez 2009; 47(4): 69-77. [ Links ]

15. Melo N, Gallego GJ, Restrepo LF, Peláez A. Blanqueamiento vital y métodos para la valoración de su eficacia y estabilidad. CES Odontol 2006; 19(2): 53-60. [ Links ]

16. Gallego G, Zuluaga O. Combinación de tres técnicas de blanqueamiento en dientes no vitales. reporte de un caso. CES Odontol 2006; 19(2): 47-52. [ Links ]

17. Bertone M, Zaiden S. Blanqueamiento dentario aplicaciones clínicas. Revista de la Facultad de Odontología UBA 2008. 23; 54/55: 19-25. [ Links ]

18. Giménez B, Forner L, Amengual J. Laser y blanqueamiento dental. revisión bibliográfica. Rev Asoc Univ Valenciana Blanq Dent 2007; 1: 7-11. [ Links ]

19. Petkova M. Efectos clínicos y estructurales del blanqueamiento dental. Odontol Sanmarquina 2005; 8(2): 34-36. [ Links ]

20. Zalkind M, Arwaz JR, Goldman A, Rotstein I. Surface morphology changes in human enamel dentin and cementum following bleaching: a scanning electron microscopy study. Endod Dent Traumatol 1996; 12(2): 82-88. [ Links ]

21. Marson, FC, Sensi, LG, Vieira RCC, Araújo E. Clinical evaluation of in office dental bleaching treatments with and without the use of light- activation sources. Oper Dent 2008; 33(1): 15-22. [ Links ]

22. Sarret D. Tooth whitening today. J Am Dent Assoc 2002; 133(11): 1535-1538. [ Links ]

23. Kihn PW. Vital tooth whitening. Dent Clin North Am 2007; 51(2): 319-331. [ Links ]

24. Joiner A. The bleaching of teeth: a review of the literature. J Dent 2006; 34(7): 412-419. [ Links ]

25. Zeconis R, Matis BA, Cochran MA, Al Shetri SE, Eckert GJ, Carlson TJ. Clinical evaluation of in- office and at- home bleaching treatments. Oper Dent 2003; 28(2): 114-121. [ Links ]

26. Bizhang M, Chun YHP, Damerau R, Singh P, Raab WHM, Zimmer S. Comparative clinical study of the effectiveness of three different bleaching methods. Oper Dent 2009; 34(6): 635-641. [ Links ]

27. Sulieman M, Rees JS, Addy M. Surface and pulp chamber temperature rises during tooth bleaching using a diode laser: a study in vitro. Br Dent J 2006; 200(11): 631-634. [ Links ]

28. Araujo FO, Baratieri LN, Araújo É. In situ study of in-office bleaching procedures using light sources on human enamel microhardness. Oper Dent 2010; 35(2): 139-146. [ Links ]

29. Tavares M, Stultz J, Newman M, Smith V, Kent R, Carpino E et al. Light augments tooth whitening with peroxide. J Am Dent Assoc 2003; 134(2): 167-175. [ Links ]

30. Luk K, Tam L, Manfred H. Effect of light energy on peroxide tooth bleaching. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135(2): 194-201. [ Links ]

31. Dederich D, Bushick R. Lasers in dentistry: separating science from hype. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135(2): 204-212. [ Links ]

32. Dostalova T, Jelinkova H, Housova D, Sulc J, Nemec M, Miyagi M et al. Diode laser activated bleaching. Braz Dent 2004, 15: S13-S18. [ Links ]

33. Lahoud V, Mendoza J, Uriarte G, Munive A. Evaluación de los efectos clínicos del blanqueamiento dental aplicando dos técnicas diferentes. Odontol Sanmarquina2008; 11(2): 74-77. [ Links ]

34. Berga A, Forner L, Amengual J. Blanqueamiento vital domiciliario: comparación de tratamientos con peróxido de hidrogeno y peróxido de carbamida. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006; 11: E94-E99. [ Links ]

35. Goldstein RE, Lancaster JS. Survey of patient attitudes toward current esthetic procedures. J Prosthetic Dent 1984; 52(6): 775-780. [ Links ]

text in

text in