Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.2 Medellín Jan./June 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

A family-focused oral-health toy library: Towards a new direction in oral health education1

Sandra González Ariza2; María Cristina Giraldo3; Janneth Varela4; Elisa María Peña4; Juan Pablo Giraldo4; Jorge Jhovanny Orozco4

1 Best Community Intervention Project. Awarded by Compañía Colgate

Palmolive, 2005

2 Dentist. MA in Epidemiology, CES

3 Dentist. Specialist in Health Promotion and Communication, CES

4 Dentists, CES

SUBMITTED: OCTOBER 11/2011 - ACCEPTED: MARCH 27/2012

González S, Giraldo MC, Varela J, Peña EM, Giraldo JP, Orozco JJ. A family-focused oral-health toy library: Towards a new direction in oral health education. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 23(2): 306-320.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: discovering strategies to promote motivation of personal skills must be a permanent task of oral health

professionals. The purpose of this program was to create a place, within the toy library, devoted to strengthening oral health habits, with the

guidance of trained personnel such as toy librarians and dentists, who developed ludic strategies for teaching and reinforcing oral health

knowledge among children and their families.

METHODS: this was a pre-experimental community intervention program, which evaluated

99 children between 4 and 12 years of age. Surveys were conducted in order to assess the students', parents', and guardians' knowledge

before and after their interaction with the ludic material; also, caries and dental plaque indexes were measured.

RESULTS: this training

program allowed improving the knowledge level among parents and children by 21 and 29% respectively. The average percentage of dental

plaque was 38.2 ± 18.9 showing a difference of 18.3% with respect to the initial exam. Among the surfaces with caries history, those which

had been restored were predominant (1.5 ± 2.6). The qualitative analysis of the children's perception of the games revealed that they found

them positive, nice, fun, and educational.

CONCLUSIONS: establishing an oral health toy library, as a constructive environment that involves

innovative strategies aimed at health education, allowed socialization of the studied population as well as promotion of healthy oral habits

and reinforcement of self-care among this population.

Key words: education, ludic activities, oral health, health promotion, primary prevention, strategies.

INTRODUCTION

After conducting several studies on oral health in Colombia, the country has been able to establish the dental conditions of its population, as well as a diagnosis that provides the grounds for preventive strategies aimed at improvements not only in clinical terms but also concerning knowledge and habits.1, 2 The third national study on oral health (Ensab III) concluded that oral health education and its constant reinforcement is the only way to guarantee that the population will remain healthy. Oral health indicators among the population between five and fourteen years show improvement when compared to the reports of the two previous studies, probably as a consequence of oral health promotion/prevention programs in the latest decades, as well as increments in dental service access. The aforementioned study found out that 60,4% of five-year-old children had experienced dental caries, a proportion that increased to 73,8% at the age of seven years and dropped to 13% by the age of twelve as a consequence of dental exfoliation. In five-year-old children —age of completion of deciduous dentition— a reduction of 30% in the average of teeth with dental caries was observed, and the DMT-t dropped from 4,2 in 1977-1980 to 3,0 in 1998. Although the country did not achieve the oral/dental health goals set by the WHO/FDI for this population group, the fact that 39,6% of these children did not have dental caries experience is an indication of the moderate effect of primary dentition health levels.3

Oral health may not be isolated from socialization of education, as health education is a process that promotes behavioral, conceptual and attitudinal changes regarding health, disease and service access, and it also reinforces positive behaviors.4

The development of health education community programs requires much more than just delivering information; it is a process that must begin by studying the communities and inquiring into them in order to become familiar with their lifestyles, concepts, ambitions, needs and concerns in relation to health and disease.5

An environment that encourages oral health learning would be the adequate setting for promoting actions that allow the population to have a greater control on their own oral health and to opt for behaviors that increase their life quality.6, 7

Using places that are frequently visited by the community may be an effective resource to gather the population around the proposed activities. Assuming oral health promotion as an enjoyable activity comes from the idea of combining health with playing games, thus creating the term saluteca oral (oral health toy library) which definition stems from the word ludoteca (toy library), described as a ludic, educational, recreational and cultural community place intended not only to kids and youngsters but to the whole community. This place encourages the kids' free playing and favors intergenerational activities and educational events for all the family, with an emphasis on values related to life together as well as to children's care and development.8

Since knowledge alone is not enough to ensure the acquisition of habits and behavioral changes, and as such knowledge is determined by structural factors related to economy, education, culture and the health systems themselves, a characterization of the families was performed in order to identify segments of their environment that would guide us in the development of strategies to reinforce positive messages in oral health.

The goal of this program was to create a space in the toy library especially devoted to oral health, with the participation of trained personnel such as toy librarians and dentists, who by means of games and recreational teaching approaches would reinforce knowledge and develop the adequate strategies to enable children and their families learning about oral health, paving the way for the acquisition of new healthy habits.

METHODS

This was a pre-experimental community intervention study with the intention of assessing 99 children between four and twelve years of age, attending the Pequeños Visitantes toy library of Fundación Solidaria La Visitación at the neighborhood of Manrique San Pablo, Medellín (Colombia). The kids' oral health state was evaluated before and after the ludic intervention with intervals of six months by means of dental caries indexes (Nyvad, modified by doctor Alfonso Escobar in 1991)9 and dental plaque indexes (O'Leary).10 Also, a questionnaire on oral health knowledge was formulated to both, children and their guardians, before and after the educational lectures and the interactions with ludic material. Pedagogical groups were formed in order to develop the educational strategies, which consisted on training children, parents and guardians, as well as the toy librarian, in the use of educational games related to oral health.

This program was approved by the Ethics Committee of CES University. Parents, guardians and children, as well as the institution, were explained the goal of the study and they all signed a letter of consent, thus voluntarily accepting their participation.

The clinical evaluation was performed by two researchers previously standardized by an expert, with a Kappa coefficient of 0,83 and 0,79. Each dentist used a portable dental chair equipped with lighting, air compressor, and basic sterile instrumentation for each child. The clinical procedure followed these steps: a) 2% erythrosine staining was applied in order to detect supragingival plaque and to register the stained surfaces on the index; b) prophylaxis was performed with rubber cups; c) drying was done with air and cotton; d) each surface was evaluated with a blunt tip probe in order to diagnose dental caries.

The strategy used to design educational material followed the parameters suggested by specialized educators (psychologists, social workers, designers, and dentists) who selected the elements for the children to decode, analyze and criticize the mass media messages and, at the same time, to evaluate how these media influence customs, attitudes and social behavior. It also included the process of health communication suggested by PAHO in 1985,11 which consists of six stages: Strategy planning and selection; channel and material selection; elaboration of preliminary materials and tests; execution; evaluation of the effectiveness, and feedback to improve the program. A focus group with teachers and kids was conducted at the beginning in order to find out about their opinions, which served as a basis for developing the educational strategies. A survey on the kids' and their guardians' oral health knowledge was conducted before and after both the educational activities and the interaction with ludic material.

The ludic material was designed following the principle of ''enjoyment-education'' programming,12 which pretends the health information with entertaining purposes to be attractive, easy to understand, and able to influence behaviors. It also included a short story named ''Star War'', which lasts fifteen minutes and was at the center of all the activities in order to make the information easy to identify by the kids in each stage of the program. During the focus groups the kids contributed to develop these materials, which consist of:

A video that tells a science fiction story which is supposed to be at the center of the entire program. It narrates the adventures of three special agents and their space trip to the planets of dental protection: ''Pasturio'', ''Seditaturno'', and ''Cepillolandia''. Their mission consisted on avoiding ''Plaquetón'' to invade the Earth with his germs after many years of maintaining oral health on Earth.

A primer for the persons in charge of the oral health toy library so that the information is reproduced among all the attending children. It presents activities related to diverse oral health reinforcement topics and is accompanied with a special toy for this topic.

An activity booklet with guided activities for each kid to perform according to the corresponding oral health reinforcement topic. This booklet is intended to be taken home and shared with the family. Toys designed with the intention of reinforcing the topics discussed in each session and which, according to the rules of the toy library, may be borrowed by the kids to be brought home and shared with their families.

Toys of the first phase, sensitization with the short story and the topic to be discussed, familiarity with the characters. Parcheesi decorated with some of the ''Star War'' characters to create a sense of belonging in the kids by means of familiarization with the characters in the initial phase of the program. It reinforces activities such as telling stories and following rules. A jigsaw puzzle—a toy consisting on forming a picture correctly accommodating its parts—. In this case, the images are taken from the ''Star War'' video with the intention of strengthening familiarity with the characters and some healthy habits. ''Put Motas his tooth''. This game stimulates confidence in the child; it consists on putting teeth on a beaver while being blindfold.

Toys of the second phase, parts of the mouth, oral hygiene elements. Dominoes depicting oral hygiene elements; it allows children perceiving the objects as close to them, and helps them improve the ability to form sets and to recognize shapes that are similar. ''Draw the star''. It is designed to encourage team work and entertainment. This toy combines graphic language with the purpose of having children interiorize oral health vocabulary; the participants should identify the terms in order to progress in the game.

Toys of the third phase, food intake, dental caries, gingival diseases. ''Don't lose your tooth''. Having a list of words related to oral health and parts of the mouth, one of the contestants chooses one term for another participant to guess. Inaccuracies must be avoided because teeth are lost as mistakes are made. ''Staircase'': This game allows children recognizing the foods that are beneficial or harmful to oral health by relating them to penalties and rewards in the staircase.

Statistical analysis

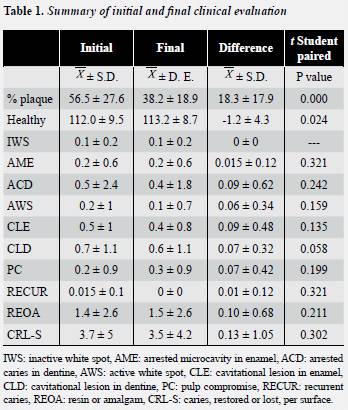

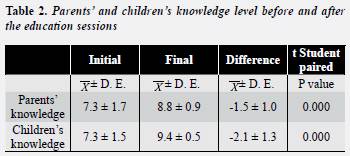

The SPSS software version 8.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL) was used for analyzing the information. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate normality distribution of the quantitative variables; since most of the variables presented a normal behavior, Student's t test for paired samples was used to compare differences between the two moments (before and after the intervention).

Averages and standard deviations were used to summarize the information by means of tables, and a significance level of 0,05 was always presumed for the statistical tests.

RESULTS

Clinical analysis

For the development of this community intervention project 99 children were initially evaluated. The ages ranged between four and twelve years, with an average of 8.8 ± 1.8 years. Males were predominant as in 58.6% (56 kids). In the first phase of the program, clinical evaluations were performed in order to determine their oral health state before and after participation in it. In this first clinical examination, we found out that the average percentage of soft plaque on the surfaces was 58.6 ± 27.5, and the average percentage of healthy surfaces was 112.37 ± 9.36. Among the unhealthy surfaces, amalgams and resin were predominant (1.72 ± 2.81); the number of surfaces with cavitational lesions in enamel, dentin and pulp compromise was 4.01 ± 4.84.

During the course of the program there was a desertion of 32%; therefore, the second clinical examination was performed on 67 children. The analysis of the final data was made with the children who participated from the beginning to the end of the program, so it did not affect the final results because when comparing the initial clinical evaluation between the 99 and the 67 children, it was similar when the kids lost for the second evaluation were excluded.

Data exploration showed again predomination of the masculine sex, with 56.7% (38 kids). This final analysis showed that the average percentage of soft plaque was 38.2 ± 18.9, with a reduction of 34.8%. Concerning the number of healthy surfaces, at the time of the initial exam there were 112.0 ± 9.5. Among the number of surfaces with dental caries history, the restored ones were predominant (1.5 ± 2.6). No significant statistical differences were found by using the Student's t test for paired samples between initial and final diagnosis of the active and inactive white spots, as well as in active and still microcavity in enamel, dentine and with pulp compromise (table 1) .

Family characterization

80% of the families live in their own houses and the rest live in rented houses; all of them have access to public services (aqueduct and sewer system) and toilet The general conditions of the houses are good (64%); it is important to note that 12% of the houses were under construction. 68% of the houses have cement floor and the rest of them have tiled floor. In general, adequate hygiene was observed, and 32% of the families had pets. The average amount of persons per household is 4.4 and they have a minimum of one bedroom and a maximum of five. 86% of the study population is affiliated to the General System of Social Security in Health, being Susalud the Health Service Provider (EPS) with the most number of members (41%), and Cafesalud with the less members (5.3%); the remaining 24% have been classified by the Sisben but have not defined their situation of affiliation to the health system.

Analysis of knowledge

Certain level of ignorance was observed in topics related to teeth changing, as well as to the importance of both dentitions. Topics such as oral hygiene and kind of foods revealed significant data. In general, the health of guardians is good; some parents taught themselves oral hygiene, while others learned it from their family dentist. Most of the parents believe in the importance of teaching their children themselves; nevertheless, not all of them do this teaching, in fact, some of them think taking care of deciduous teeth was not important as they will be exfoliated. Oral health implements are not used by all the families; some of them do not include dental floss in their shopping for financial reasons or because they do not perceive it as an element of daily use. Visits to the dentist is not a priority among these families; although most of them are affiliated to an EPS or the Sisben, some of them do not use the dental services offered because they do not have time or because they think they do not need them as they don't have maladies or treatments to be monitored. Several parents have not been to the dentist's office in more than six months. The second survey showed knowledge increase in all of these aspects, for example in dentist visits, which are not only performed to solve dental problems but also to achieve a good oral health, or in the importance of taking care of deciduous teeth; finally, the use of dental floss is now part of daily oral hygiene among this population (table 2).

Analysis of the toys

A qualitative analysis of the children's perception of the toys evidences that they found these toys to be positive, nice, fun and educational. These are some of the opinions expressed by them:

Star War video. ''The characters were very cute and we would like them to move their mouths; the topic of saving the world is great. It should include more characters''.

Don't lose your tooth and Put Motas his tooth. ''We really enjoyed it and we laughed a lot; we also learned why people lose their teeth''

Draw the star. This is one of the toys the children enjoyed the most. These are some of their suggestions: ''to make more cards; what we like the most is that we learn so much by playing and drawing, also because it is related to teeth and foods which is the topic we are learning''.

Staircase. ''We really like the pictures on the board, and because it sends some players back to the special squares, also because the pictures of oral hygiene are very cute and colorful''.

Parcheesi, jigsaw puzzles, and dominoes. ''They are very pretty; you should make more so that everyone can play''.

DISCUSSION

The latest fifteen years have witnessed a reduction in the severity and prevalence of oral diseases among the population of developed countries. With a systematic organization of oral care, the improvement of individual attitudes has been achieved, favoring the oral health of children and youth as the patterns of dental caries that used to affect them have changed, and as a result more adults are able to maintain their natural teeth in subsequent years.13

On the contrary, some reports suggest the existence of increments of oral health problems in some developing countries. This is particularly true in countries were oral health promotion and prevention programs aimed at the communities are not implemented.14

Since the incorporation of healthy habits occurs during infancy and early childhood, the programs seeking to promote oral health must be focused on the postnatal period. Nevertheless, programs to prevent dental decay in high risk children have been obtaining limited success. But the programs focused on the needs and culture of the communities seem to have more benefits.15

In a study by Al-Omiri Al-Wahadni, and Saeed (2006),13 they found out that Jordanian children had more prevalence of gum diseases and dental caries than European children because, according to their study, programs with great emphasis on oral health have been developed in Europe, and therefore the children are aware of oral care. They also found out that a high number of Jordanian children brush their teeth at least once a day but this activity is not arranged or supported by their parents. They believe this is due to lack of oral health education.13 These concepts differ from what has been reported in the present study which found out that after ludic intervention there was a decrease in the percentage of bacterial plaque thanks to a family approach, as parents, guardians and children reinforced their knowledge and understood that oral health is as important as the health of any other body organ, and now they pay more attention to it.

In another study, carried out by Rosamund Harrison and Tracy Wong, the researchers report that modifying the mothers' oral hygiene habits results in the adoption of adequate oral health behaviors in their families.15 This situation is similar to the one reported in the present study.

Nurko, Skur and Brown performed a study in which they compared dental caries prevalence in children whose parents had participated in oral health education programs and children whose parents had never received such education. They found out that dental caries prevalence was higher among the kids whose parents have never participated in an oral health education program.16 Conversely, another study, carried out in Jordan, reports that in spite of the high level of parents' knowledge, children present poor oral hygiene habits, and the same study also found out that few parents help their children at the time of brushing their teeth.13

Other studies demonstrate that early education on oral hygiene practices aimed at both parents and children may reduce caries prevalence.13, 15, 16 They recommend motivating the mother or the guardian to follow self-care instructions, and to bring the kid to periodical preventive dentist visits to avoid oral diseases.15

Similar recommendations were proposed in the present study, in which the parents were made aware of the importance of paying attention to the way their children brush their teeth, and to offer help if needed.

In a study made in Pelotas (Brazil), the authors found out some risk factors that contribute to dental caries incidence in children. Such risk factors are: Unemployed parents or independent workers; parents with less than eight years of education when the baby is born; insufficient height of the kid at the age of twelve months; children who have never been seen in a health center in their first six years; children who do not wash their teeth even once a day, and children who eat candies at least once a day.17 Many of these factors were found in the families of the children who participated in the present program, and afterwards a decrease in caries incidence was observed; a similar situation occurred with other factors such as the amount of times the kids brush their teeth a day and candy consumption, since the other factors could not be modified due to the type of study applied.

Another factor that contributes to the prevalence of diseases of the oral cavity among children is poor access to dental care by kids with few socioeconomic resources. Dental caries increase in these children has been one of the most serious problems in developing countries. Besides the few socioeconomic resources, lack of education has also been reported as another factor that influences the periodontal state. The recommendation for them is oral health education.18

A study conducted in Jordan reported that parents and children had been informed about oral cavity diseases but the knowledge offered had not been communicated in an effective manner because the conditions under which this communication took place had not been the right ones: dental offices and medical centers, with limited time, and during drastic treatments with dental extractions.14 This is why creating a positive environment for learning about oral health, such as the one created for this study, favors the increment of actions that allow the population to have a greater control on their own oral health and to opt for behaviors that increase their life quality.6, 7

Oral health prevention programs may be effective to improve knowledge, modify attitudes, and foster healthy practices. But to achieve it, oral hygiene requires appropriate and continuous instruction, coupled with efficient motivation.18

The present study demonstrates that implementation of this kind of programs arises interests among the benefitted community, by involving the population in the process of material construction and by promoting empowerment. Nevertheless, desertion of some families may limit the scope of the program, and therefore it is important for future studies on this field to consider the elements discussed in this study in order to generate innovative instruments for health education as part of a complete communication strategy that provides the community with positive reinforcement of oral health care. Consequently, it is important to follow the recommendations made by González-Martínez19 and Vanobbergen20 in their studies: to take into account the regional characteristics of the places where the strategies are implemented, and to promote oral hygiene in early stages.

Similarly, this kind of programs must make part of governmental plans, by articulating them to activities aimed at health promotion in institutions of health services and by encouraging research in this field and therefore greater efforts to implement this model for the adequate participation of the community in these activities.

CONCLUSION

Providing children and their parents with an adequate place for learning by means of a community intervention program and by using ludic methods of teaching and knowledge reinforcement allowed developing the right strategies to instruct them and to reinforce positive habits on oral health topics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To all the people who made this program possible: Colgate Palmolive Co., Fundación Solidaria La Visitación, UPB's School of Design, Universidad CES, mister Gonzalo Álvarez for his help in the statistical analysis; to all the children and their families, and to all the other members of Ludoteca Pequeños Visitantes.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Sandra González Ariza

Email address: sgonzalez@ces.edu.co

Universidad CES

Calle 10A N.º 22-04

Phone number: (057-4) 444 05 55 exts. 1618, 1515

Fax number: 311 35 05

Medellín, Colombia

María Cristina Giraldo Zuluaga

Email address: mcgiraldo@ces.edu.co

Universidad CES

Cra. 43A N.º 52 Sur-99

Phone number: (057-4) 305 35 00 ext. 2265

Fax number: 311 35 05

Sabaneta (Antioquia), Colombia

REFERENCES

1. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud, Ascofame. Investigación Nacional de Morbilidad oral, 1965-1966. Bogotá: El Ministerio; 1971. [ Links ]

2. Instituto Nacional de Salud. Segundo Estudio Nacional de Morbilidad Oral, 1977-1980. Bogotá: Instituto Nacional de Salud; 1980. [ Links ]

3. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Serie de documentos técnicos. III Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal. Bogotá: El Ministerio; 1999. [ Links ]

4. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Guía para el diseño, utilización y evaluación del material educativo en salud, Washington: OMS; 1984. [ Links ]

5. Calvo B. La descentralización de los sistemas educativos. Revista mexicana de investigación educativa. [revista en línea] 2003, [fecha de acceso 25 de abril de 2004] URL disponible en: http://www.comité.org.mx/revista/pdfs/carpeta/18/18investtempres.pdf [ Links ]

6. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Carta de Ottawa para la Promoción de la Salud. Conferencia Internacional OMS y la Asociación Canadiense de Salud Pública. Toronto: OMS; 1986. [ Links ]

7. Lee J. Promoción de la salud en Colombia ¿responsabilidad de las aseguradoras? Revista Coomeva 2003; 53: 26-27. [ Links ]

8. Colgate Palmolive Company. Advances and progress in oral health trough oral care education. Scientific proof of the effectiveness of a global oral health education initiative. New York: Professional Audience Communications; 1998. p. 10-37. [ Links ]

9. Martignon S, Téllez M. Criterios Icdas: nuevas perspectivas para el diagnóstico de la caries dental. Rev ACOP 2007; 5(1): 31-37. [ Links ]

10. O'Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol 1972; 43(1): 38. [ Links ]

11. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Manual de técnica para una estrategia de comunicación en salud. El proceso de comunicación en salud una visión de conjunto. Washington: OPS, OMS; 1985. [ Links ]

12. Coe GA. Comunicación y promoción de la salud. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación Chasqui 63 [en línea] 1998 [fecha de acceso 27 de enero de 2005] URL disponible en: http://chasqui.comunica.org/coe.htm [ Links ]

13. Al-Omiri MK, Al-Wahadni AM, Saeed KN. Oral health behavior attitudes, knowledge, and behavior among school children in North Jordan. J Dent Educ 2006; 70: 179-185. [ Links ]

14. Rajab LD, Petersen PE, Bakaeen G, Hamdan MA. Oral health behaviour of school children and parents in Jordan. Int J Pediatr Dent 2002; 12: 168-176. [ Links ]

15. Harrison RL, Wong T. An oral health promotion program for an urban minority population of preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31: 392-399. [ Links ]

16. Nurko C, Skur P, Brown JP. Caries prevalence of children in an infant oral health educational program at a WIC clinic. J Dent Child 2003; 70: 231-234. [ Links ]

17. Peres MA, Latorre MRDO, Sheiman A, Peres KGA, Barros FC, Hernández PG et al. Social and biological early life influences on severity of dental caries in children aged 6 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005; 33: 53-63. [ Links ]

18. Taani DQ. Relationship of socioeconomic background in oral hygiene, gingival status, and dental caries in children. Quintessence Int 2002; 33: 195-198. [ Links ]

19. González-Martínez F; Sánchez-Pedraza R, Carmona- Arango L. Indicadores de riesgo para la caries dental en niños preescolares de La Boquilla, Cartagena. Rev Salud Pública 2009:11(4): 620-630. [ Links ]

20. Vanobbergen J, Martens L, Lesaffre E, Bogaerts K, Declerck D. Assessing risk indicators for dental caries in primary dentition. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29(6): 424-434. [ Links ]

text in

text in