Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versión impresa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.2 Medellín ene./jun. 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

Ethno-dentistry flora of the embera indigenous communities from Antioquia's Medio Atrato region

José Ubeimar Arango Arroyave1; María Evalina Iságama2

1 Agronomy Engineer, Msc. Advisor of the Organización Indígena de

Antioquia (OIA), 1998-2008. Teacher at the Agriculture Technical

Program, Institución Educativa Presbítero Rodrigo Lopera Gil, Peque

(Antioquia), and principal of Hogar Juvenil Campesino de Peque

2 Dentist of Universidad de Antioquia; member of the embera chamí

ethnic group

SUBMITTED: NOVEMBER 11/2011 - ACCEPTED: MARCH 27/2012

Arango JU, Iságama ME. Ethno-dentistry flora of the embera indigenous communities from Antioquia's Medio Atrato region. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 23(2): 321-333.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the forest areas traditionally used and managed by the embera native communities living in the

biogeographic Chocó's tropical rainforests ecosystems contain several plants of dental use.

METHODS: this study used ethnographic

research approaches supported by photographs, botanical samples, forms, field work notes, and taxonomic identification.

RESULTS:in the form of an inventory, this work presents the floristic composition and some ethno-botanic notes on the species identified and

recognized by the native communities from the Medio Atrato river region which have a medical/cultural value for the oral health

of this ethnic group; five species are especially important: three genera of different growing patterns and two families, which are

used in preventive oral health.

CONCLUSIONS: this study allowed concluding that the aforementioned dental practices, and the

ancestral knowledge connected to them, are being gradually forgotten, especially by young people but even by the adult members

of these ethnic groups.

Key words: Ethno-dentistry flora, embera native community, Medio Atrato region, biogeographic Chocó, oral health.

INTRODUCTION

In many of the world' s tropical and neotropical rainforest regions, including Latin America, traditional medicine based on the use of plants plays an important role in solving local oral health needs, and it includes a great variety of phytochemical composites and knowledge that are usually unknown or disregarded by formal science but which are still the main source of treatment of adverse health situations that are treated in particular sociocultural and economic contexts which can hardly access formal health services.1 This is common among several peoples, especially among native communities living in rainforest ecosystems who maintain an active and dynamic traditional health system— although with some variations—. The use of plants for prevention and treatment of oral disorders is particularly important.

This article seeks to contribute to the knowledge of how the embera community uses some plants with enthnodentistry purposes in order to solve dental problems and to prevent periodontal diseases, by inquiring into their traditional knowledge and identifying the plants and parts used as well as the way they prepare them. The goal is to pave the way for an intercultural integration and approach between institutionalism and native communities, as a challenge that requires new perceptions and recognition of traditional knowledge in dialogue with formal or scientific knowledge.

AREA OF STUDY AND ITS CHARACTERISTICS

This study was carried out in the embera territories of Antioquia's Medio Atrato region, specifically with the native communities from Jarapetó of the municipality of Vigía del Fuerte, and Chageradó and Isla of the municipality of Murindó. The embera native population in Antioquia's Medio Atrato is divided into dobidá (embera from the river) and san juaneños in Vigía del Fuerte, and Oibidas and Eyavidas (embera from the forest and mountain) in Murindó; the latter are commonly known as katíos, located in a total protected area of 89.099 ha, with a population of 1.608 natives2-6 (figure 1).

This region makes part of what is known as biogeographic Chocó, located among vegetal formations of very humid tropical forest, tropical wet forest and premontane wet forest;7 the average sunlight hours range between 1.000 and 1.300 yearly, with an average relative humidity of 70 to 90%, and precipitations as high as 5.000 mm of surface water in average per year.8

METHODS

This research project was conducted with an approach related to qualitative research methods of an ethnographic nature and within a process of participatory action research (PAR),9-11 whose ''proposed research object is considered to be a subject of it''; therefore, these methodological phases and processes were followed: Phase I: Secondary source information search as in libraries, specialized documentation centers, conversations with both indigenous and non-indigenous consultants, congresses, seminaries and forums.

It also included searching and reading the reports of different workshops, projects and ethnobotanic work at the OIA archive and documentation center. Phase II: The fieldwork allowed collecting both ethnodentistry information and vegetal sample material in forest areas and successional forests. This material was adequately collected, pressed and kept for its subsequent taxonomic identification. Several semi-structured interviews were performed during this phase in different places and times, including interviews to fourteen production developers, six health promoters, three traditional botanists, two groups of women, four teacher representatives, two general governors, fourteen local governors, and six indigenous leaders of the selected communities, for a total of forty-nine interviewees. This phase also involved taking notes and photographs, completing forms and making field trips, as well as two workshops with emphasis in quick and participative rural surveys, field diaries, and direct and participative observation. Phase III: botanical identification, and analysis, compilation and synthesis of the ethnobotanic information gathered.

RESULTS

Floristic composition, botanic characteristics, and parts of the plants used

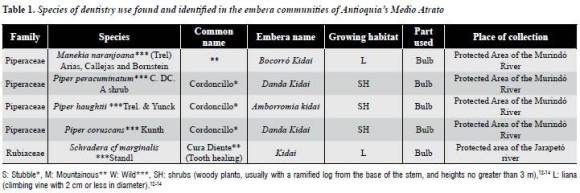

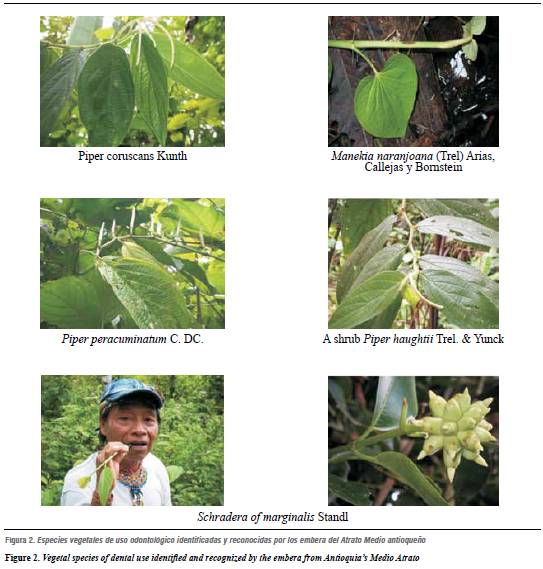

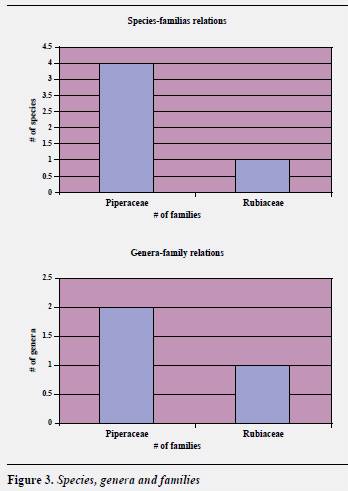

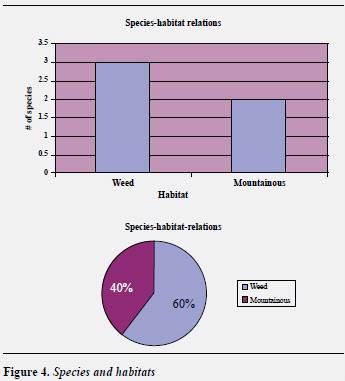

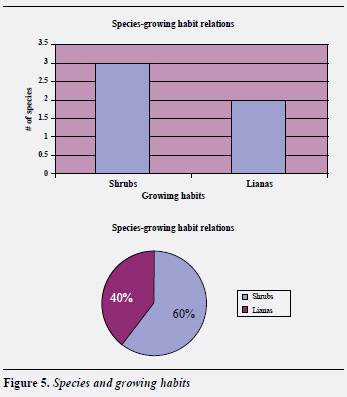

The five botanic samples identified* and described (table 1 and figure 2) belong to five species, three genera, and two families; most of the species are of the Piper genus (Piperaceae), with three species, followed by Manekia of the same family and Schradera (Rubiaceae) with one (figure 3) . Considering species per habitat, three of them are weeds, followed by two mountainous species, corresponding to 60 and 40% respectively (figure 4). In terms of growing habits, three of the species are shrubs and two are lianas, also corresponding to 60 and 40% (figure 5).

It is also important to point out that all of the species in this study (five) are found in wild state in forests and successional forests (stubble-fallow fields), and they are usually manipulated as they have material and symbolic uses as well as associated social practices, as a matter of fact, their generic and specific names in embera are related to their equivalent formal taxonomic names. As for the parts used, all of them are bulbs (soft ending stems).

Dental uses

The plants of the genera Piper, Manekia and Schradera, known by the embera from the Medio Atrato with the generic names of Kidai or Kidía, are used with preventive purposes and in a periodical manner, at least once a month, to ''dye the teeth'', ''make them strong'' ''solid'', ''resistant'', and ''to prevent caries''.

The liquid released by the parts of these plants (soft stems, bulbs, flowers and fruits) are bitter and acid,15

[...] it is very probable that the natives control dental caries with it, as well as the microorganism of caries and periodontal pockets. They also help to prevent the destruction of the teeth's roots and calculus formation.

[...] ''the same liquid is used to fill dental porosities''.

Preparations

The aforementioned genera of plants are prepared as follows: The part of the plant is chewed until liquid is released, then it is spread with the tongue all over the teeth once or twice, without gargling, until the teeth gain a bright, solid, black color. This color lasts for about a week or two, and as it loses intensity the same procedure is repeated. This treatment is performed in one day, and during this time it is recommended not to consume any kinds of food.

DISCUSSION

The species found in this study are usually found in wild state and similar uses of them, especially of the species of the Piper genus, are not reported in other ethnic groups or in other rural areas, although it is important to mention that the embera from Catrú (Bajo Baudó-Chocó)15 use species such as Schradera cf marginalis, of which both flowers and fruits are used, while the embera from Medio Atrato only use the soft stems and the bulbs of the same species. Also, in Catrú it has another function, as a sociocultural custom, for the ceremony of Jemené or puberty, in which all adults and youngsters should chew their fruits. The same author15 reports other species that are used in this community with dentistry purposes, such as: Schradera sp., known in embera as koretada, of which both bulbs and fruits are used, Petiveria alliacea (anamú), Carica papaya (papaya), Erythroxylon coca (Coca), Zingiber officinale (ginger); out of these four species, they use the root. These roots are usually macerated and then mixed with liquids such as ''viche'', known in other parts as ''tapetusa'', ''chirrinche'' or ''aguardiente casero'' (homemade liquor or ''moonshine'') in order to make a mouthwash. This procedure is repeated several times ''to relieve toothache''.

Among some piperaceaes related to aspects of dental use, the same authors of this article found a plant known as ''curadiente'' (toothcuring) (Piper holtonii (Trel.) Trel. & Yunck), in the Las Lomas district of the municipality of Peque (Western Antioquia) —a former indigenous territory—. Such plant belongs to the same genus of some of the plants collected in Medio Atrato, and its bulb is used for ''caries prevention'' by some inhabitants of the district. In the same municipality,16 it has been reported that some people use macerated leaves of fuchsia magellanica (Eupatorium sp.-Asteraceae) in ''cataplasm'' to treat toothache. Similarly,17 four species belonging to the same number of families are mentioned as being popular in some regions of Colombia for treating dental problems: mango (Chlorophona Tinctoria-Moraceae) teología (teology) (Euphorbia dichotoma-Euphorbiaceae), quiebra ojo (eye cracking) (Asclepias curassavica-Asclepiadaceae), dinde (Mangifera indica-Anacardiaceae). The author points out that out of the mango they use the adult leaves, while of the remaining three species they use the latex they release.

Concerning some species of the Rubiaceae family, it is important to mention Isertia laevis, known in the region of Medina (Cundinamarca, Colombia) as ''palo santo'' (holy stick), and used with medical purposes.18 This species, as well as Elaegia utilis, has been studied by part of the Phytochemistry Research Group (GIFUJ) and by the Dentistry Research Center of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; their fractions and subfractions, obtained from their leaves, have demonstrated several biological activities, such as inhibitor of oral cavity bacteria associated to dental caries.19, 20

It is also important to mention that some urban areas still have deep-rooted peasant, mestizo, afro-descendent and Amerindian traditions so that people resort to social practices that include the use of some plants that are considered to have curative or therapeutic dental properties; that is the case of plants such as tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum) in cities like Medellín,21 as well as species domesticated and commercialized by urban merchants in the same city, such as salvia (Austroepatorium inulaefolium), calendula (Calendula officinalis), lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratos), cardamom (Eletaria cardamomun), and papaver (Papaver somniferum).22 In other contexts, such as some European cities like Valencia, Spain,23 up to nine species for treating oral disorders have been reported, one of them being a plant of American origin: tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum).

Resuming our argumentation, in the case of Colombia, 24 the III Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal (National Study on Oral Health), carried out in 1998, informed some oral health practices, by reporting that 6.3% of the population use items such as toothpicks, carbon, ash, salt, and plants for oral hygiene; these elements are especially related to the population with lower levels of education. Similarly, it showed that 16% of the population use homemade remedies in situations such as toothache (rinses with salt and water, rinses with plants, ''the electric filling'', alcohol drops, nail polish, liquor gargling, just to name a few).

In the case of the embera of our study area, treatment and healing of diseases, including some oral conditions, are performed by botanists and traditional doctors, known in the embera language as Jaibanás, or the ones who possess the knowledge and wisdom for the right use of medicinal plants in their ethno-pharmacologic and therapeutic aspects. We could also find out that embera women also know a great deal of the use and management of medicinal plants, especially the ones of dental type, thus allowing the permanence of these practices and knowledge.

Several authors25 suggest that traditional medical cultures understand illnesses from their etiology, signs and symptoms based on a common symbolic imaginary both for the patient and the treating doctor or dentist, and this means a negotiation between tradition and modernity, the self and the other, which should not be forgotten but instead re-created in the conventional medical and dental model.

In the same way, another author claims26 that the illness, being of a dental nature or not, is a conceptual reality itself that exists in an extensive social and cultural context which provides it with certain forms based on which it is explained and treated.

Although certain ethno-pharmacological traditions are still practiced, specifically in the case of dentistry, they tend to be each time less frequent; also, the extensive experience and knowledge of the diverse cultures inhabiting tropical areas, including the Amerindian ones, tend to gradually disappear each time at a faster pace as new generations begin to abandon their traditional lifestyles.27 Concerning this matter, during the workshops and interviews conducted for this study we could observe that less than 20% of the total population, excluding people of advanced age, still use this kind of traditional practices based on the aforementioned plants, thus producing an increasing loss of this type of knowledge among the younger population, who in their words ''feel embarrassed'', especially before non-indigenous people, due to the esthetic reasons (the black color of the teeth), appearing as having bad oral hygiene.

CONCLUSIONS

A great deal of medicinal flora, including its dental use by communities living in rural areas, especially native communities, is not known or recognized by conventional medicine. In spite of several attempts and studies, there is still a gap between the formal medical sciences and traditional medicine, which is also an evidence of lack of ethnobotanical research projects and phytochemical studies showing possible and potential molecules and metabolites of medical and dental action.

This study approached the dentistry knowledge and treatment strategies by the embera from the Medio Atrato who use plants with therapeutic purposes. It could then become a reference point for programs that seek projects of intercultural management of oral health for different institutions that approach indigenous organizations and that watch over the rights and survival of these communities.

Projects and studies such as the one presented here try to point out aspects and perspectives of local knowledge and social practices of an ethnodentistry and botanical nature that may at a certain point be in contact, in a transdisciplinary perspective, with specialties such as dentistry, public health, health sciences, natural sciences, and social sciences.

It is necessary and important to continue studying the aspects related to traditional medical and dental knowledge still maintained by afrodescendent, countryside and native peoples as a measure and strategy of public health, in order to raise awareness and to search for other options to the current Colombian health system aimed at ethnic groups, including native communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Chief Councils of Murindó and Vigía del Fuerte. Special thanks to Levi Dumazá, health promoter of the Community of Jarapetó, and Jilo, indigenous leader of the Community of Isla, who played an important role in this project. We would also like to thank the members of the OIA Health Program who are constantly supporting and counseling native communities in their processes of reconstruction and cultural identity.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

José Ubeimar Arango Arroyave

Dirección: Calle 45F N.º 70A-93

Medellín, Colombia

Correo electrónico: egoronomia@hotmail.com

María Evalina Iságama

Dirección: Diagonal 43C N.º 34-20

Bello, Vía Machado

Correo electrónico: evalina85@hotmail.com

REFERENCES

1. Ricker M, Daly D. Botánica económica en bosques tropicales: principios y método para su estudio y aprovechamiento. México: Diana; 1998. [ Links ]

2. Arango JU, Peñarete D. Estrategias de producción, extracción y protección en los territorios de las comunidades embera de Jarapetó, Jengadó y Ñarangué (Atrato Medio antioqueño). [Tesis Ingeniero Agrónomo e Ingeniera Forestal]. Medellín: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias; 2000. [ Links ]

3. Centro de Cooperación Indígena. La tierra contra la muerte: conflictos territoriales de los pueblos indígenas en Colombia. Houghton J, ed. Bogotá: Anthropos; 2008. [ Links ]

4. Corporación para el Desarrollo Sostenible del Urabá-Organización Indígena de Antioquia. Diagnóstico Ambiental de Urabá. Apartadó: Corpouraba- OIA; 2002. [ Links ]

5. Duque LM, Espinosa I, Gálvez AC, Herrera D, Turbay SM. Chajeradó: Río de la caña flecha partida. Bogotá: Colcultura; 1997. [ Links ]

6. Salazar CA. Dayi Drua-Nuestra tierra: comunidad y territorio indígena en Antioquia. Medellín: Gerencia Indígena; 2000. [ Links ]

7. Holdridge LR. Ecología basada en zonas de vida. San José de Costa Rica: Instituto Interamericano de Ciencias Agrícolas; 1982. [ Links ]

8. Desarrollo Rural Integrado, Corporación para el Desarrollo Sostenible del Chocó. Evaluación de tierras, agricultura, especies menores, bosques comunales, pesca en la región del Medio Atrato. Quibdó: Diar-Codechocó; 1988. [ Links ]

9. Fals Borda O. Conocimiento y poder popular. Bogotá: Siglo XXI; 1995. [ Links ]

10. Cano M. Investigación participativa: inicios y desarrollos. Revista Ciencia Administrativa Nueva época [en línea] 1997 [fecha de acceso 24 de marzo de 2012]; URL disponible en: http://www.uv.mx/iiesca/revista2/mili2.html [ Links ]

11. Vizer F. Metodología de intervención en la práctica comunitaria: investigación-acción, capital y cultivo social. Revista Ciberlegenda [en línea] 2002 [fecha de acceso 24 de marzo de 2012]; 10 URL disponible en http://www.uff.br/mestcii/vizer2.htm [ Links ]

12. Allaby M. The Concise Oxford dictionary of botany. Oxford: University Press; 1992. [ Links ]

13. Álvarez R. Análisis estructural de dos bosques de guandal ubicados en zonas con diferente nivel de inundación. [Tesis ingeniero forestal]. Medellín: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias; 1993. [ Links ]

14. Londoño A. Análisis estructural de dos bosques asociados a unidades fisiográficas contrastantes en la región de Araracuara (Amazonia colombiana). [Tesis ingeniero forestal]. Medellín: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias; 1993. [ Links ]

15. Iságama M. Plantas medicinales y sus diferentes usos en la comunidad indígena de Catrú-Chocó. [Tesis odontólogo]. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, Facultad de Odontología; 2005. [ Links ]

16. Benítez D. Estudio florístico en bosques relictuales del municipio de Peque- Antioquia. [Tesis ingeniero forestal]. Medellín: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias; 1997. [ Links ]

17. Uribe L. Botánica. Bogotá: Voluntad; 1972. [ Links ]

18. García BH. Flora medicinal de Colombia: Botánica médica. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional Colombia; 1996. [ Links ]

19. Alvarado A. Actividad antimicrobiana de extractos, fracciones y subfracciones obtenidas a partir de hojas de Isertia laevis sobre bacterias asociadas a caries dental. [Tesis maestría en Ciencias Biológicas]. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; 2007. [ Links ]

20. Téllez M, Perdomo M. Evaluación de la actividad antimicrobial de la fracción activa de Isertia laevis obtenida de dos metodologías de extracción sobre Streptococcus mutans y Streptococcus sobrinus. [Tesis bacteriólogo]. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; 2009. [ Links ]

21. Sarrazola AM, Martínez E, Agudelo AA, Alzate M, Arango LC, Aristizábal M et al. Prácticas sociales asociadas con el uso de la planta de tomatera en afecciones bucales en un grupo de adultos. Rev Cubana Estomatol [en línea] 2006 [fecha de acceso 13 de septiembre de 2010]; 43(2) URL disponible en http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=0034-750720060002script=sci_issuetoc [ Links ]

22. Jaramillo G, Gaviria A, Gómez MI, Gutiérrez C, Molina R, Pinedo V. El expendedor de plantas de la ciudad de Medellín: su caracterización social y su saber en salud bucal. Rev Fac Odont Antioq 2007; 19(1): 100-112. [ Links ]

23. Fresquet Febrer, Blanquer G, Galindo M, Gallego F, García de la Cuadra R, López JA et al. Inventario de las plantas de uso popular en la ciudad de Valencia. Revista Medicina y Ciencias Sociales [en línea] 2001 (13) [fecha de acceso 20 de abril de 2011]. URL disponible en: http://www.uv.es/ medciensoc/num2/inventario.html [ Links ]

24. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. III Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal. Bogotá: el Ministerio; 1998. [ Links ]

25. Urrea F, Puerto F. Itinerarios terapéuticos y comunicación médica intercultural en dos poblaciones urbanas de Cali y Buenaventura. En: Pinzón C, Suárez R, Garay G, eds. Cultura y salud en la construcción de las Américas. Bogotá: Colcultura, Comitato internazionale per lo sviluppo dei Populi; 1994. [ Links ]

26. Quevedo E. La relación salud-enfermedad: un proceso social. En: Cardona A, ed. Salud y Sociedad. Bogotá: Zeus; 1998. p. 105-166. [ Links ]

27. Wenzell SR. Medicinal plants use and knowledge in the context of economic and social transformations. En: Annual meeting of Southern Anthropological Society. Florida; 1992. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en