Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.2 Medellín Jan./June 2012

REVIEW ARTICLE

The smile and its dimensions

Miguel Ángel Londoño Bolívar1; Paola Botero Mariaca2

1 Orthodontist, Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia UCC, at Medellín

2 Orthodontist, Universidad CES. Assistant Professor, Universidad CES

and Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia. Research Coordinator in the

Orthodontics Graduate Program, UCC, School of Dentistry, Envigado,

Colombia

Londoño MA, Botero P. The smile and its dimensions. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 23(2): 353-365.

ABSTRACT

As a common human expression that conveys a variety of emotions in intentional and unintentional ways, the smile must be characterized by a series of features that allow identifying all possible alterations in its physiological, anatomical, and functional aspects. This article will approach the smile from different perspectives, classifications, and standards for its assessment. By means of a thorough analysis of the smile and its elements, formal and functional alterations in the esthetic zone will be identified in order to suggest the best therapeutic options to provide patients with comprehensive treatment.

Key words: dental esthetics, facial expression, smile.

INTRODUCTION

Smiling is a common human expression that communicates pleasure or amusement, but it may also be an involuntary expression of anxiety or several other emotions such as anger or irony.1 It is considered to be a normal reaction to certain stimuli, innate to individuals (we are born with it), and not linked to sociocultural aspects.2, 3 The smile is an important part of an individual's physical stereotype and perception, and it is also important in the judgment that the others have of our appearance and personality; therefore, smile asymmetry plays an important role in the perception of beauty.4, 5

From a physiological point of view, a smile is a facial expression produced by flexing 17 muscles located around the mouth and the eyes. Considering muscle functions, the smile is produced in two different stages. During the first one, the upper lip and the nasolabial folds are contracted, with participation of the levator labii superioris, the zygomatic major muscle, and some upper fibers of the buccinator. In the second stage, or the final one, there is contraction of the periocular muscles so as to support maximum elevation of the upper lip, thus producing half-closed eyes.6

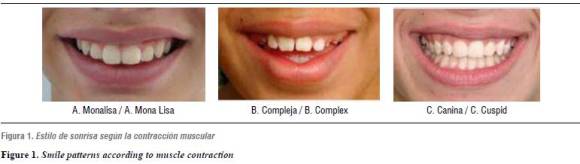

Depending on the lips raising direction and the muscle group involved in the smile, it is classified into three categories: The cuspid smile, characterized by participation of all the levator labii superioris, thus exposing both teeth and gingival tissue. The complex smile, characterized by the simultaneous action of levator labii superioris and lower lip depressors, and the commissure smile or Mona Lisa smile, in which the zygomatic major muscles bring the commissures up and outwards, followed by a gradual elevation of the upper lip as in an arch shape, so that the center of the lip becomes lower than its lateral portions7, 8 (figure 1).

Another way of classifying the smile considers the level of consciousness involved. The voluntary smile may or may not be motivated by an emotion; the static one is extendable and reproducible, and the involuntary one, which is induced by gladness and has a dynamic nature, expresses authentic human emotions but cannot be sustained for long periods of time.8

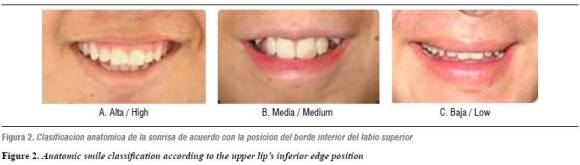

From an anatomic point of view, it may be classified, according to gingival line localization, as high, medium, and low, depending on the relation between the upper lip inferior edge and the upper incisors and their gingiva. If the gingival line when smiling displays 100% of the anterior tooth and even a portion of the gum, it is considered as a high smile; if the smile line exposes between 75 and 100% of the tooth it is called a medium smile, and if it only shows 50% or less of the incisor it is considered to be a lower smile3, 10, 11(figure 2).

An ideal smile depends on the symmetry and balance of facial and dental characteristics such as color, shape, and teeth position, considering that shape determines function and that the anterior teeth play a critical role in the patient's oral health.12 Estimation of a harmonic smile includes assessment and analysis of the ''smile zone'', which, depending on its shape, may be: straight, curved, elliptical, arched, rectangular, or inverted (figure 3).12, 13

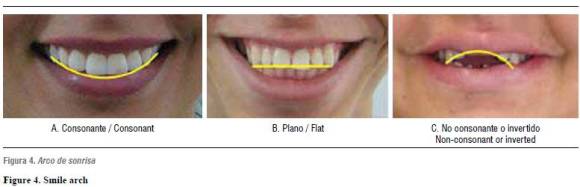

An important component of the smile is the ''smile arch'', which is formed by the relation of the upper incisal edges and the lower lip contour on smiling. It may be classified as consonant if the incisal edges of the upper teeth follow the lower lip contour, flat if the incisal edges of the upper teeth are straight, and non-consonant, reverse or inverted if the incisal edges of the upper teeth are aligned in an arch opposite to the lower lip line (figure 4). In younger patients this arch is normally more accentuated.12, 14-17 There are two factors that influence the smile arch: the palatal plane inclination in relation to the Frankfort plane, that may increase dental display, and the upper arch shape, particularly the anterior segment configuration, as a wider arch presents a smaller curvature of such segment with a greater probability of producing a flat smile arch. Projection of the upper lip inferior edge when smiling may be more accentuated in younger patients and reduced in adults; besides, it depends on the interincisal distance (mesodistal distance between central and upper lateral teeth).12, 14-16, 18

Another important factor to consider is the buccal corridors, described as the space between the posterior teeth vestibular surfaces and the lip commissures at smile. They have been classified as wide, somehow wide, medium, somehow narrow, and narrow, with prevalence of 28, 22, 15, 10, and 2% respectively (figure 5). Clinically, a wide buccal corridor may be included in the list of problems and treatment plans. Nevertheless, reduction of buccal corridors must not be judged as a reason to expanding a normal maxillary.3, 11, 19

SMILE STHETICS

Several criteria have been attempted as a reference to establish whether a patient presents a harmonic ideal smile or if, on the contrary, it is somehow altered. An esthetic smile depends on three key elements: lips, gums and teeth.7

In terms of the lips, there exist several important aspects related to morphology, length, width, volume, symmetry, and thickness.12, 20 Length (the distance between the nose base and the lip) must be of 20 to 22 mm in young women, and of 22 to 24 mm in young men, with an incisor display of 3 to 4 mm in women and 1 to 2 mm in men.21, 22 It is important to bear in mind that tooth display with lips at rest is directly related to age, because as it increases there occurs some muscle atrophy which results in lip reduction, loss of its structure, and consequently, its extension. As a result, there occurs a decrease of 1.5 to 2 mm in the upper incisor display on smiling, the smile becomes transversally wider and vertically narrower, thus increasing the buccal corridor.12, 22

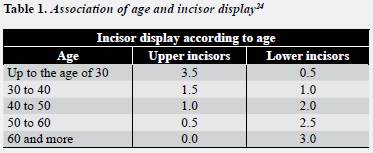

In 1978, Tkoat reported this alteration as a loss of upper incisors display and greater exposure of lower incisors through time. Their study shows that up to the age of 29 approximately 3.3 mm of the upper incisor are displayed with lips at rest, at the age of 39 years 1.5 mm is displayed, at the age of 49. 1 mm is shown, at the age of 59, 0.4 mm, and finally at the age of 60 the incisor is totally covered. Similarly, they reported that lower incisor display evolves directly proportional to age, it is, while at the age of 29 0.5 mm of the lower incisor is displayed, at the age of 60 this figure increases to 2.95 mm with lips at rest23, 24 (table 1).

Lips length increase in men is usually twice as much as in women;21 nevertheless, this enlargement is not significant, and subjects with a short lip at the age of 7 will still have it short until they are 18. Similarly, lip thickness also increases, showing greater increase levels at points A and B than in upper Labralle and lower Labralle.12 Lips width at smile should be at least half the face width; volume is the variable that generates thick, medium, or thin lips, and symmetry must be the mirror image of both lips at smile, it is, having a similar contour.12, 25

In terms of the gum, it is important to take into account first that the relation between the gingival margins of upper anterior teeth plays an important role in the crown's esthetic appearance and therefore in the smile. Four aspects must be considered for its assessment: in the first place, the margin of the upper central teeth must be at the same level, the margin of both laterals should be located 1 mm more coronal than that of the central ones, and the gingival margin of the canines must beat the same level than that of the central incisors, thus creating the seagull effect26 (figure 6).

As a second aspect, the gingival zenith is considered the most apical point of the gingival tissues along the tooth longitudinal axis, it is located distal to the longitudinal axis of the central teeth and the canines, and it usually concurs with the axis of the upper lateral and the mandibular incisors.12, 27 Thirdly, the vestibular gingival margin must simulate the teeth cement-enamel junction, and there should be papilla between the teeth so that the smile's esthetics would be the ideal one.25, 27 Finally, dental structure plays an important role in a smile's esthetics; the adequate proportions between length, width, shape, and the matrix of teeth among themselves and with the adjacent ones are key factors when smiling.

The average central incisors and canines length in men is 10 mm, in a scale between 7.7 and 11.9 mm, and it is 1 mm smallerin women, while lateral incisors are approximately 1.4 mm smaller in both sexes.26-28 Lateral incisors width is approximately two thirds the width of the central incisors, which provides the upper anterior segment with a better esthetics. These size relations between central and lateral incisors have been called ''golden proportions''. 28, 29 Finally, when referring to dental matrix, it means the different shades observed in the esthetic zone that directly influence the perception of an ideal smile.28

SMILE ASSESSMENT

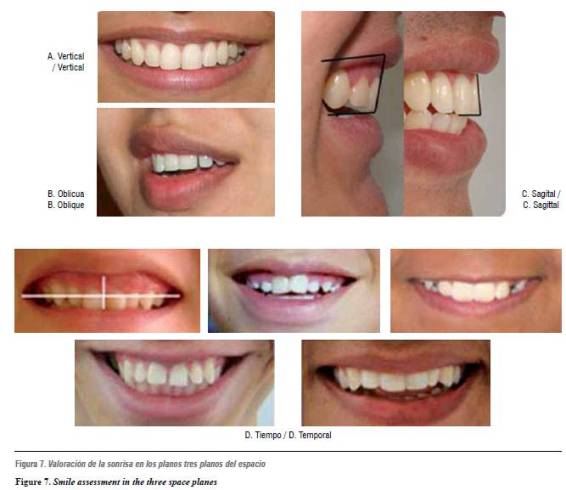

A full evaluation of a smile must include four aspects: 3, 8, 30, 31 the vertical dimension, which implies assessment of incisor display with lips at rest; the sagittal dimension, or assessment of incisors overjet and angulation, the oblique dimension, that includes analysis of the smile arch and the palatal plane direction, and finally the time factor, which includes aspects such as growth, maturing, and aging (figure 7).

In most of the cases, evaluation of these four dimensions guarantees a comprehensive smile analysis. Detailed esthetic judgment can only be made seeing patients frontally during conversation in order to assess alignment of the dento-facial middle line and right/left symmetry of canines and premolars.32, 33

Besides these dynamic and static records, it is important to make biometric measures in order to establish aspects such as inter-commissure distance, lips filtrum, interlabial gap, and smile curvature, which would allow precisely identifying any type of smilealteration.3, 29, 34-38

A digital method of videographic assessment has been recently described, thus obtaining dynamic records of both smile and speech, and allow recording anterior teeth and gums during function. It is useful to make all the analysis normally obtained in a parametric and static way with conventional photography besides assessment of smile changes achieved during treatment.3, 30, 34-38

SMILE ESTHETIC ALTERATIONS: THE GINGIVAL SMILE

A distorted relation among the smile components (lips, teeth and gum) may produce an unattractive smile, as the one that displays more than 2 mm of gum (line of high smile), which is known as gingival smile.6, 24 This is one of the most common alterations among the population, with a prevalence of 26%,6 and it may be produced by several factors:

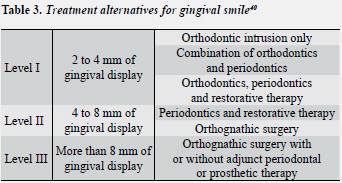

The first one would be a short upper lip, which is considered a structural type of alteration when caused by a length reduction, or a functional alteration if mobility is altered, with a hypermobile lip.24, 39 The second factor would be vertical maxillary excess, which is a skeletal volumetric alteration with several degrees of severity depending on the quantity of gingival display at smile: level I if gingival display is between 2 and 4 mm, level II if 4 to 8 mm of gingiva are displayed, and level III if showing more than 8 mm of gingiva.24, 40

The third and last factor would be gingival margin position alterations caused by delayed passive eruptions with apical migration of the gingival margin once the tooth's active eruption is completed.6, 24, 40 Some authors suggest that this alteration is common in adults only, but there are some children and youngsters with excessively small anatomic crowns that should be included in this range of alterations.41-44

In 2004, Chu et al classified this type of gingival margin position alteration according to the level of osseous ridge in relation to the cement-enamel junction. In type IA passive eruption, the osseous ridge is located apically to the cement-enamel junction, there exists enough amount of gum adhered, and the gingival margin is located incisal to the cement-enamel junction; characteristics observed in type IIA passive eruption are the same, but it presents an inadequate amount of keratinized gingiva. Active eruption types IB and IIB are similarly classified. In active eruption IB, the osseous ridge is located at the cement-enamel junction and there exists an adequate amount of adhered gingiva; besides, the gingival margin is located incisal to the cement-enamel junction.

It also differs from type IIB in the amount of keratinized gingiva, which is smaller in the latter. All of these factors must be considered to determine the actual gingival compromise when little incisor display occurs when smiling.40

In 2004, Coslet et al reported the short tooth syndrome as one eruption alteration in which coronal length is reduced due to an excess of gum or a reduction of dental structure, thus producing poor incisor display.41, 42 Other frequent alterations in the esthetic zone are gingival asymmetries or gingival margin position alterations, a situation in which the patient requires esthetic treatment to achieve adequate gingival architecture and to meet the aforementioned requirements, that were reported by Kokich in 1996.26

GINGIVAL SMILE TREATMENT MODALITIES

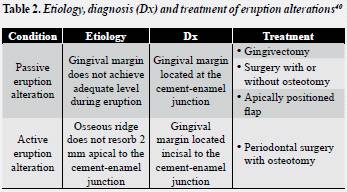

There are several therapeutic approaches reported in the literature for adjusting esthetic zone alterations during smile, and they may require the interdisciplinary participation of all the dental specialties. Once the etiology of the problem has been identified, a possible solution is suggested, and it may range from orthodontic treatment to surgical orthodontic treatment or periodontal surgery. When dealing with a case of eruption alteration,40 the treatment plan must consider the amount of gingival display and the alveolar ridge position in relation to the cement-alveolar junction. Treatment options may range from gingivectomy, flap surgery with or without osteotomy, apically positioned flap, or periodontal surgery with osteotomy in case of active eruption alteration40 (table 2).

Vertical maxillary excess as an etiologic factor offers different treatment alternatives depending on the level of excess or the severity of the problem,24 and it usually requires the intervention of several specialties. The solution could be achieved with an orthodontic approach alone, or in combination with periodontal therapy and restorative dentistry in case of level I vertical maxillary excess. If severity of the vertical maxillary excess increases to level II, it is, between 4 and 8 mm of gum display, besides the aforementioned therapies it would require the intervention of maxillofacial surgery with maxillary impaction. Finally, when vertical maxillary excess surpasses 8 mm of gum display (level III), the initial approach would be orthognathic surgery and then, if necessary, a combination of other specialties (orthodontics, periodontics, and dental rehabilitation)24, 40 (tables 2 and 3).

When the etiology of the esthetic zone alteration is a short upper lip, the literature reports muscle reposition for smile correction, as well as the application of botulinum toxin as a possible solution, as its pharmacological effect occurs at the neuromuscular junction and it works by inhibiting acetylcholine release. This results in muscular paralysis, thus avoiding exaggerated mobility during smile, and finally in a temporary chemodenervation (temporary inhibition of nervous transmission) at the neuromuscular junction without producing physical harm to nervous structures.39, 45, 46

There are several treatment modalities to treat alterations of gingival margins location, and the decision would depend on an adequate diagnosis; out of the range of possibilities, Kokich (1993) reports periodontal surgery to correct soft tissue shape, orthodontic intrusion and extrusion, and restoration of the shortest teeth.26, 47-50

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Paola María Botero

Dirección: Calle 4 Sur N.° 43AA-26

Teléfono: 311 37 85

Fax: 311 69 39

Correo electrónico: pboterom@gmail.com

REFERENCES

1. Hulsey CM. An esthetic evaluation of lip-teeth relationships present in the smile. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop1970; 57(2): 132-144. [ Links ]

2. Freitas-Magalhães A, Castro, E. (eds.). The neuropsychophysiological construction of the human smile2009. En: Freitas-Magalhães A. (ed.). Emotional expression: the brain and the face. Portugal: University Fernando Pessoa Press; 2009. p. 1-18. [ Links ]

3. Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: part 2. Smile analysis and treatment strategies. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 124(2): 116-127. [ Links ]

4. Beall AE. Can a new smile make you look more intelligent and successful? Dent Clin North Am 2007; 51(2): 289-297. [ Links ]

5. Ker D, Chan R. Esthetics and smile characteristics from the layperson's perspective. A computer-based survey study. J Am Dental Assoc 2008; 139(10): 1318-1327. [ Links ]

6. Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. The gingival smile line. Angle Orthod 1992; 62(2): 91-100. [ Links ]

7. Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod 2002; 36(4): 221-236. [ Links ]

8. David M, Sarver D. The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 120(2): 98-111. [ Links ]

9. Tjan AH, The JG. Some esthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 51(1): 24-28. [ Links ]

10. Geron S, Atalia W. Influence of sex on the perception of oral and smile esthetics with different gingival display and incisal plane inclination. Angle Orthod 2005; 75(5): 778-784. [ Links ]

11. Nanda C. Dynamic smileanalysis in young adults Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 132: 307-315. [ Links ]

12. Davis NC. Smile design. Dent Clin North Am 2007; 51(2): 299-318. [ Links ]

13. Dietschi D. Optimizing smile composition and esthetics with resin composites and other conservative esthetic procedures. Eur J Esthet Dent 2008; 3:14-29. [ Links ]

14. Frush JP, Fisher RD. The dynesthetic interpretation on the dentogenic concept. J Prosthet Dent 1958; 8: 858-881. [ Links ]

15. Waldrop TC. Gummy smiles: the challenge of gingival excess: prevalence and guidelines for clinical management. Semin Orthod 2008; 14: 260-261. [ Links ]

16. Chiche GP. Prótesis fija estética en dientes anteriores. Barcelona: Masson; 2002. [ Links ]

17. Morley J. Macroesthetic elements of smile desing. J Am Dent Assoc 2001; 132: 39-45. [ Links ]

18. Salama M. The aesthetic smile: diagnosis and treatment. Periodontology 2000 1996; 11: 18-28. [ Links ]

19. Moore T. Buccal Corridors and smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005; 127: 208-213. [ Links ]

20. Robbins JW. Differential diagnosis and treatment of excess gingival display. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1999; 11(2): 265-272. [ Links ]

21. Ghosh NR. Facial soft tissue harmony and growth in orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod 195; 1(2): 67-81. [ Links ]

22. Peck D, Peck L. Some vertical lineaments of lip position. Am J Orthop Dentofacial Orthop 1992; 101: 519-524. [ Links ]

23. Tkoat D. The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent 1978; 39(5): 502-504. [ Links ]

24. Mallat E. Prótesis fija estética: enfoque clínico y multidisciplinario. España: Elsevier; 2007. [ Links ]

25. Shyam D. Dynamic smile analysis: Changes with age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 136(310): 310e1-310e10. [ Links ]

26. Kokich VG. Esthetics: the orthodontic periodontic restorative connection. Semin Orthod 1996; 2: 21-30. [ Links ]

27. Greensteln D,Cavallaro J Tarnow D. When to Save or extract a tooth in the esthetic zone: a commentary. Compend Cont Educ Dent 2008; 29(3): 136-146. [ Links ]

28. Kokich VG, Kokich VO. Interrelationship of orthodontics with periodontics and restorative dentistry. Elsevier Press: Missouri; 2005. [ Links ]

29. Donitza A. Creating the Perfect smile: prosthetic considerations and procedures for optimal dentofacial esthetics. J Calif Dent Assoc 2008; 36(5): 335-342. [ Links ]

30. Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: part 1. Evolution of the concept and dynamic records for smile capture. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 124(1): 4-12. [ Links ]

31. Erdal SH. Smiles Esthetics: Perceptionand comparison of treated and untreated smiles Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:8-16. [ Links ]

32. BU Z. Esthetic factors involved in anterior tooth display and the smile; vertical dimension. J Clin Orthod 1998; 32: 432-445. [ Links ]

33. Theodore Moore KAS. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005; 127(2): 208-213. [ Links ]

34. Spear FM, Kokich VG. A multidisciplinary approach to esthetic dentistry. Dent Clin North Am 2007; 51(2): 487-505. [ Links ]

35. Van der Geld PA, Oosterveld P, Van Waas MA, Kuijpers- Jagtman AM. Digital videographic measurement of tooth display and lip position in smiling and speech: reliability and clinical application. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 131(3): 301-308. [ Links ]

36. Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Van Heck G, Kuijpers- Jagtman AM. Smile attractiveness. Self-perception and influence on personality. Angle Orthod 2007;77(5): 759-765. [ Links ]

37. Ronald J, Mackley D, MS. An evaluation of smiles before and after orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 1993;63(3): 183-189. [ Links ]

38. Marc B, Ackerman D. An Evaluation of dynamic lip-tooth characteristics during speech and smile in adolescents. Angle Orthod 2004; 74: 43-50. [ Links ]

39. Polo M. Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) for the neuromuscular correction of excessive gingival display on smiling (gummy smile). Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;133(2):195-203. [ Links ]

40. Chu SJ, Karabin S, Mistry S. Short tooth syndrome: diagnosis, etiology, and treatment management. J Calif Dent Assoc 2004; 32(2): 143-152. [ Links ]

41. Fernández-González RA, Simonneau-Errando, G. Altered passive eruption. Repercussions on dento-facial aesthetics. RCOE 2005; 10(3): 289-302. [ Links ]

42. Coslet JG, Weisgold A. Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan 1977; 3: 24-28. [ Links ]

43. Morrowa J, Jonesc N, Wilsona N. Clinical crown length changes from age 12-19 years: a longitudinal study. J Dent 2000; 28(7): 469-473. [ Links ]

44. Rey D, Botero P, Camargo L. Manejo estético periodontal y ortodóncico del segmento anterior. Revista CES 2006; 19(2): 41-45. [ Links ]

45. García M. El diccionario médico interactivo. [en línea] [fecha de acceso enero de 2011]; URL disponible en: http://www.portalesmedicos.com/diccionario_medico/index.php/Botox [ Links ]

46. Rosenblatt A. Lip repositioning for reduction of excesive gingival display: a clinical report. Int J Period Rest Dent 2006; 26: 433-437. [ Links ]

47. Kokich V. Gingival contour and clinical crownlength: Their effect on the esthetic appearance of maxillary anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1984; 86(2): 89-94. [ Links ]

48. Fakhry A. Enhancing restorative, periodontal, and esthetic outcomes through orthodontic extrusion. Eur J Esthet Dent 2007; 2(3): 312-320. [ Links ]

49. Allen EP. Surgical crown lengthening for function and esthetics. Dent Clin North Am 1993; 37(2): 163-179. [ Links ]

50. Kovich V. Esthetics and anterior tooth position: an orthodontic perspective. Part I: Crown length. J Esthet Dent 1993; 5(1): 19-23. [ Links ]

text in

text in