Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.24 no.1 Medellín July/Dec. 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

Sociodemographic differences associated to caries experience and prevalence among users of a public health network

Jairo Corchuelo Ojeda1

1 Professor, Universidad del Valle's School of Dentistry, Cali, Colombia; Public Health Sciences PhD Program, Universidad de Guadalajara, Mexico.

SUBMITTED: NOVEMBER 22/2011-ACCEPTED: JULY 12/2012

Corchuelo J. Sociodemographic differences associated to caries experience and prevalence among users of a public health network. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 24(1): 96-109.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: dental caries has been considered a public health problem; the latest national studies have shown some

reduction in caries prevalence, but in unequal way and in some regions only. This study explores caries experience and its possible

connections to social factors and oral health practices of users of dental services in 40 institutions of the Red Pública Departamental

(state-based public health net) in Valle del Cauca, Colombia.

METHODS: this was a cross-sectional analytic study on 1.566 users;

both traditional and modified DMFT (decayed, missing and filled teeth) indexes were registered, as well as caries experience, caries

prevalence and DMFT levels. The participants filled out a structured questionnaire which included sociodemographic variables

and oral health practices. The estimators were calculated following the proposed design and using the statistical program SPSS®,

version 17, and Epi 3.5.1.

RESULTS: caries experience did not show significant differences by sex, and it was observed with a greater

proportion among males than among females between twelve and twenty-five years of age. Concerning ype of social security coverage,

the patients with smaller amounts of caries experience were the ones covered by the contributive regime —although after the age

of 34 all of them already presented caries experience—. The percentage of caries prevalence found was 64.3% (CI 95%: 62-66%).

CONCLUSIONS: both caries experience and caries prevalence were associated to age, social security coverage, and belonging to

vulnerable population groups.

Key words: dental caries, prevalence, DMFT index, health disparities, public health.

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is still a critical aspect of general health conditions in Latin America and the Caribbean because of the significant position it occupies among the world's oral-dental morbidity, its treatmentrelated costs, and the possibility of adopting effective prevention measures. The strategy suggested by PAHO's Directing Council in 19971 clearly emphasized the importance of preventing oral-dental diseases by establishing comprehensive oral health programs, strengthening national capacities and encouraging sustainable oral health interventions among almost all its 38 member states.

Since 1995, forty national surveys on oral health have been carried out in the region. Their data suggest a remarkable decrease (ranging between 35 and 85%) of dental caries prevalence.2 Nevertheless, the amount of oral-dental diseases is still high in comparison to other world regions. The most relevant symptoms of the current health crisis in the Americas include conditions such as poor and unequal health services, the changing tendencies of oral-dental diseases, cost increments, and reduced investment in public oral health programs. Several studies conducted in Latin America have revealed some increment of caries levels measured by means of DMFT (amount of decayed, missing and filled teeth), and in close relation to age.3-7 In a study by Carosella et al,8 multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that both oral hygiene techniques and socioeconomic levels are significantly connected when predicting caries risk.

In 2009, Colombia's Ministry of Social Protection provided some guidelines for monitoring the oral health goals set by the Public Health National Plan.9 It prompted local administrations to locate information on DMFT status in order to determine the level of evolution of such goals. Such guidelines originate form a prospective record of information collected by means of direct assessment of the target population.

Dental caries has long been considered a public health problem; the latest national studies have shown some reduction in caries prevalence, but in an unequal way and in some regions only.

The Third National Study on Oral Health carried out in 1998 showed that the average national DMFT index was 2.3 for twelve-year olds, and 2.5 for the region where the study population is located; nevertheless, as this is an average figure, evident indicator differences appear due to development levels of the diverse regions, cities, areas, and populations living standards, so it is important to mention these differences since baseline. In addition, there are no reports on associated factors that allow developing a risk model.10

This study implied identifying caries prevalence considering cavitated and non-cavitated carious lesions. No studies are available in this region of the country as to determine the actual state of caries, caries experience, and possible associated factors.

This study explores caries experience and its possible connections to social factors and oral health practices of users of dental services in 40 institutions of the Red Pública Departamental (state-based public health net) in Valle del Cauca, Colombia.

METHODS

This cross-sectional analytic study included a simple random sample. To select the sample, the total population treated at the dental services was considered, with a confidence level of 95% and a precision of 0.10 (Epidat 3.1), obtaining an initial sample of 1.424 patients which was overestimated by a 10% for possible losses, resulting in a final sample of 1.566 patients. Informed consents were obtained before evaluations, and in the case of underage patients with previous approval by their parents. A questionnaire was used to measure social variables and a clinical instrument to assess caries and dental plaque conditions.

In each of the participating institutions of forty municipalities of Valle del Cauca, one dentist was trained to establish the oral health baseline, following the Ministry of Social Protection's guidelines for both traditional and modified DMFT; it was standardized in the corresponding registration forms as community plaque index11 and registration of sociodemographic variables.

Standardization of the clinical instrument provided by the Ministry of Social Protection had a 9% inter-examiner discrepancy. Standardization of the community dental plaque index yielded concordance kappa values of 80%.The form that examiner dentists filled out included these variables: age, population group, type of social security, gender, geographic region, number of target teeth, carious teeth with cavitation, carious teeth without cavitation, filled teeth, teeth lost due to caries, teeth lost for other reasons, and healthy teeth. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System criteria (ICDAS II) were used.12 A pilot test was conducted in order to standardize this instrument and to evaluate intraand inter-examiner differences. The format to be filled out by patients included variables related to routines and practices in terms of diet, hygiene practices, marital status, education level, occupation, and dental service use. A pilot test was later applied to verify validity of the structured survey, by applying this questionnaire to 48 patients from a population with similar characteristics, in order to spot difficulties and to verify whether the surveys really measured the target topics.

An informed consent form was previously completed by each patient, in compliance to the regulations set by the Ministry of Health's Resolution 8430 of 1993.13 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital of Cartago, which was officially responsible for the execution of this project.

The clinical examination exclusion criteria were: general health systemic alterations (leukemia, cancer, respiratory infection or other); acute lesions of the oral cavity (abscesses, dental pain, herpes, etc.); information on third molars was not included at the time of clinical examination.

The clinical data were registered during sixteen weeks each weekday; in those hospitals that accepted clinical evaluations only once a week due to personnel availability, the evaluation days were systematically alternated in order to obtain patients' evaluations in equal conditions. The forms to be filled out by patients were handed in before entering for dental assessment, with a 70% response rate.

Dental plaque data registration was the last activity of the clinical evaluation. Patients were requested to rinse their mouth for 30 s with a mouthwash containing a disclosing substance, and then dental surfaces were examined according to what had been established for the community plaque index.

Statistical analysis. The frequency of DMFT and associated factors was calculated. The estimators were calculated following the study's design and using the statistical package SPSS®, version 17, and Epi info 3.5.1. The strength of association was calculated by means of odds ratio (OR), with confidence intervals of 95%, making the corresponding adjustments according to the design. Finally, a multivariate analysis was performed by means of logistic regression, taking into account crude estimators, as well as those adjusted by regression.14

RESULTS

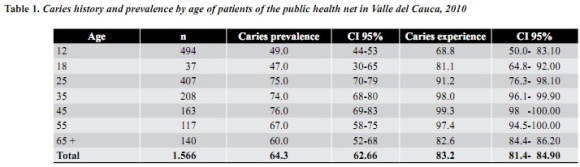

1.566 patients were evaluated; out of them, 61% were females. Twelve-year old population (31.5%) and twenty-five year old population (25.9%) were the ones with the most frequency. The percentage of caries prevalence found was 64.3% (CI 95%: 62-66%), with the lowest prevalence between the ages of twelve and eighteen; 68.8% of the twelveyear old kids had experienced caries (proportion of patients with one or more decayed, missed or filled teeth due to caries), noticing a significant increase with age (table 1).

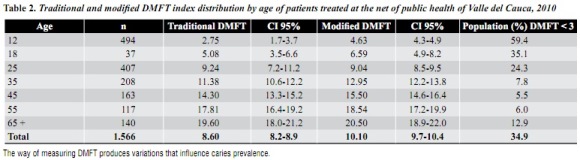

An 8.6 traditional DMFT index (decayed, missed, or filled teeth, as developed by Klein, Palmer and Knutson in 1935) was found, as well as a 10.1 modified DMFT index (this includes caries without cavitation) (table 2). The simple regression analysis suggested that type of social security, population group, education level, amount of dental plaque on dental surfaces, sweets consumption, and age are associated to DMFT. The DMFT index at the age of twelve years was 2.8 in females and 2.5 in males, with no significant differences (p > 0.05).

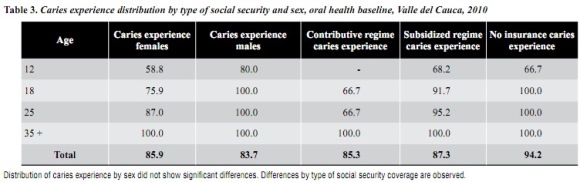

Caries experience did not show significant differences by sex, and it was observed with a greater proportion among males than among females between twelve and twenty-five years of age.

According to type of insurance, the patients with smaller amounts of caries experience were the ones covered by the contributive regime —although after the age of 34 all of them already presented caries experience— (table 3).

DMFT presented unequal distribution by type of social security coverage, with lower DMFT indexes among the patients covered by the contributive regime which at the age of twelve was 1.2, compared to a DMFT index of 3.3 and 5.0 among the ones covered by the subsidized regime and the noninsured patients respectively.

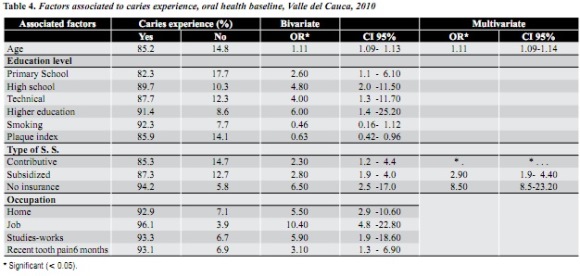

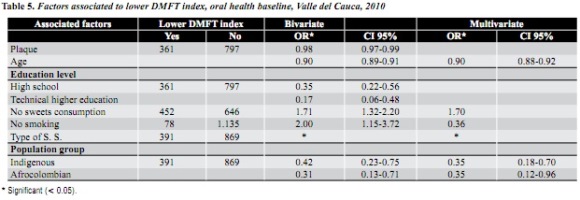

Social factors associated to caries experience include education level, type insurance, occupation, smoking status, and biological factors such as age and presenting some kind of dental pain during the last six months (table 4). The DMFT index, on the contrary, seemed to be associated to other factors such as population group and amount of plaque found in dental surfaces (table 5). The greatest DMFT index at the age of twelve was associated to population groups such as indigenous, afrodescendants and displaced people. At the age of twenty-five, besides indigenous and afrocolombians, the type of social security coverage was also associated. Among the groups of patients aged thirty-five and over, the DMFT index was not associated to any social variable.

Concerning the multivariate analysis by means of logistic regression, the best model showed statistically significant associations that explain caries experience (p < 0.05) between two factors: age and type of social security (table 4). Some interactions occurred between plaque and type of social security in relation to caries experience (p < 0.05), and between age and type of social security in relation to caries experience, OR of 1.13 (CI: 1.00-1.27).

Interactions between type of social security and education level, sweets consumption, smoking status, population group, and presence of plaque, having a lower DMFT index (< 3) as a dependent variable, decreased associations with education level, presence of plaque, sweets consumption, and smoking status, so that the final model included these variables only: type of social security (insurance), vulnerable population (type of population), and age.

DISCUSSION

Caries experience and prevalence measured by means of both traditional and modified DMFT index in hospitals of the public health net in Valle del Cauca showed unequal distribution by age, education level, type of social security, occupation, and certain habits such as smoking and oral hygiene, and toothache in the last six months. Oral health policies must emphasize on promotion and prevention actions since the very first years of age and seek strategies to reduce the oral health attention gaps among the population.

Caries experience among this population located at the western region of the country was 64.3%, with a prevalence difference of -0.6% compared to the one yielded by the Third National Study on Oral Health carried out in 1998. National levels of caries prevalence among twelve-year-old kids in the aforementioned study was 57%, while in the present study such prevalence was 49%, which indicates a difference of 8% among both prevalences. Nevertheless, in this study the DMFT index showed an increase of 7.6%, out of which the greatest figures occurred in the number of filled teeth, which increased by 62.5%, and the number of decayed teeth, with an 8.3% increase, while the number of missed teeth due to caries decreased by 10%.This suggests that dental services have paid greater attention to offering timely treatment and reducing damages, but more preventive actions are still needed. This study assessed both caries with and without cavitation, concluding that a DMFT increase of 72% occurred when this variable was considered.

Caries history and prevalence are affected by age, but the percentage of patients who have experienced caries is greater, reaching levels over 90% after the age of twenty-five. This is probably due to caries exposure at very early ages.

In order to analyze the situation of permanent dentition in Colombia, the Third National Study on Oral Health carried out in 1998 used caries history, caries prevalence and DMFT.12 This study also included the level of DMFT as an indicator, establishing a DMFT index lower than three as an acceptable standard for patients who by 2010 were about 22 years of age (the goal for the year 2000 was an acceptable DMFT lower than 3). This is why the DMFT index found in this study is considered to be high, as only 59.4% of twelve-year olds, and 35.1% of eighteen-years old achieve DMFT levels lower than 3.

Among the population younger than nineteen years, the ones who by the time of the clinical examination did not have caries presented a DMFT lower than 3 in comparison to the ones who already had caries (OR 0.22 CI 95% 0.01-0.45). This group of adolescents agreed with the assertion that dental problems are connected to oral health in general (p < 0.01).

Measurements by means of DMFT index result in a supplementary indicator to analyze caries profile. The standard established for each age must be taken into account as the DMFT index is proportionally and directly influenced by age.

Including social variables in health-related problems allows detecting elements connected to disparities in dental service attention and access to the conditions that are necessary to have a good oral health. The differences among individuals or groups with more caries experience are already an indication of heterogeneity, variation, difference, distribution, disproportion, and disparity.15

The simple regression analysis including caries experience and DMFT index as dependent variables yielded associations related to sociodemographic variables such as age, population group, or municipality, as well as economic variables, such as the type of insurance.

Although most of the studied population was insured and covered by the subsidized regime as an equity strategy, the obstacles for the poorer population to enjoy other key welfare components such as timely attention, resource availability (both by patients and health institutions), scarce purchase capacity, and other structural aspects must guide policy makers towards the social determinants that affect health due to a systematic presence of differences in one or more aspects among populations socially and demographically defined, or among specific population groups or geographic areas.16

The differences in terms of caries history among individuals or the groups considered to be vulnerable such as the indigenous and displaced population, or the greater prevalence of caries among the poorer population covered by the subsidized regime and the uninsured are already a clear indication of existing social disparities. The health sector's contribution in the search for equal services must be oriented towards reducing the existing socially unfair disparities, seeking equal opportunities in the use of health services by providing equal access and treatments, as well as equal quality of the services provided.17

A systematic revision of several caries-predicting models, carried out by Powell,18 demonstrated that caries experience in deciduous dentition is one of the greatest risk indicators. It shows that a lesion with cavitation offers a favorable environment for retaining dental plaque. Other studies have sought to establish a risk model; the associated factor most commonly found in the literature is the consumption of candy and sweetened drinks, as well as the presence of visible plaque, because sugars play a key role in the speed of progression of demineralization, increasing in presence of pathologic plaque without disturbance during the first eight days.19-21

Concerning daily consumption of sweets, the association estimators occurred during the first phase of analysis. Some studies have analyzed this issue more thoroughly,22 finding out that kids who eat sweets more than twice a day in between meals have 1.3 more probabilities of developing caries.

The presence of plaque and the consumption of foods rich in carbohydrates did not have individual significance and were not very strong when interacting with the type of insurance as a variable that reflects a structural determinant. These variables must be taken into account, as studies by GonzálezMartínez et al19 demonstrated an increased association in the plaque-sweets consumption relation. Similar findings were obtained by Dos Santos23 who, by relating these two variables, concluded that the amount of sugar in the diet and biochemical/ microbiological changes in the composition of dental plaque may explain the different types of caries occurring in deciduous dentition.

Limitations of the present study include analyzing the population that request dental services only, excluding the population that for several reasons do not seek such services. However, the findings constitute a baseline for decision makers to design relevant plans.

This study corroborates that taking carious lesions without cavitation into account influences prevalence measures.

We may conclude that the differences found in terms of caries prevalence and experience by exploring the relevant sociodemographic variables, demonstrate the social disparities in relation to age, type of insurance, and type of population of the patients treated at the public net of Valle del Cauca where the study was performed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To doctor Hepzy Lizeth Ospina from the Secretaría de Salud Departamental del Valle del Cauca, to Hospital Departamental de Cartago and Fundación CEGES, for all the arrangements that made this study possible; to all the hospitals of the Red Pública Departamental del Valle del Cauca.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jairo Corchuelo Ojeda

Universidad del Valle, Cali. Valle. Colombia

Email address: jairocorcho@yahoo.es

REFERENCES

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Evaluación decenal de la iniciativa regional de datos básicos en salud. Washington: OPS, 2004; CD 45/14: 9-17. [ Links ]

2. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Propuesta de Plan Regional Decenal sobre Salud Bucodental. Washington: OPS; 2006; CE138/14: 4-6. [ Links ]

3. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal. Bogotá: El Ministerio; 1999.Tomo VII. Documentos Técnicos. [ Links ]

4. Franco Cortés AM, Guzmán Zuluaga IC, Gómez Restrepo AM, Ardila Medina CM. Reemergencia de la caries dental en adolescentes. Av Odontoestomatol 2010; 26(5): 263-270. [ Links ]

5. Ortega M, Mota V, López J. Estado de salud bucal en adolescentes de la ciudad de México. Rev Salud Pública 2007; 9(3): 380-387. [ Links ]

6. Brenes W, Sosa D. Epidemiología bucal y accesibilidad a los servicios odontológicos de un grupo de adolescentes. Rev Cost Cien Méd 1986; 7(4): 331-337. [ Links ]

7. Corina C, Aristimuño R. Diagnóstico socioepidemiológico de la salud bucal en una población escolar del Estado Nueva Esparta 1999. Acta Odontol Venez [revista en línea] 2009; [fecha de acceso 18 de marzo de 2011]; 47(1) URL disponible en: http://www.actaodontologica.com/ediciones/2009/3/art6.asp [ Links ]

8. Carosella M, Milgram L, Rica MD, Ayuso MS, Fainboim F, Llorens A et al. Análisis del estado de la salud bucal de una población adolescente. Arch Argent Pediatr 2003; 101(6): 454-459. [ Links ]

9. Colombia. Ministerio de Protección Social. Aspectos metodológicos para la construcción de línea base para el seguimiento a las metas del objetivo 3 del Plan Nacional de Salud Pública. Bogotá: El Ministerio; 2010; p. 22-29. [ Links ]

10. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Centro Nacional de Consultoría CNS: IIIENSAB III; Tomo VII. Bogotá: Lito Servicios ALER; 1999; p. 84-88. [ Links ]

11. Corchuelo J. Sensitivity and specificity of an index of oral hygiene community use in relation to three indexes commonly used in measuring dental plaque. Colomb Med 2011, 42(4): 448-457. [ Links ]

12. Ismail AI, Sohn W, Tellez M, Amaya A, Sen A, Hasson H et al. The international caries detection and assessment system (ICDAS): and integrated system for measuring dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006; 34: 1-9. [ Links ]

13. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Normas Científicas, Técnicas y Administrativas para la Investigación en Seres Humanos. Resolución 008430.Bogotá: El Ministerio; 1993; p. 53-54. [ Links ]

14. Zhang J, Kai F. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998; 280: 1690-1691. [ Links ]

15. Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002; 56: 647-652. [ Links ]

16. Starfield B. Improving equity in health: a research agenda. Int J Health Serv 2001; 31: 545-566. [ Links ]

17. Sem AK. ¿Por qué la equidad en salud? Pan Am J Public Health 2002; 11(5-6): 302-309. [ Links ]

18. Powell V. Caries prediction. A review of the literature. Community Oral Dent Epidemiol 1998; 26: 361-371. [ Links ]

19. González-Martínez F, Sánchez-Pedraza R, CarmonaArango L. Indicadores de riesgo para la caries dental en niños preescolares de La Boquilla, Cartagena. Rev Salud Pública 2009; 11(4): 620-630. [ Links ]

20. Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries Res 2004; 38: 204-211. [ Links ]

21. Nascimiento F, Mayer MPA, Pontes P, Pignatari ACC, Weckx LLM. Caries prevalence levels of Mutans Streptecocci, and gingival and plaque and indices in 3 to 5 years old mouth breathing children. Caries Res 2004; 38: 572-575. [ Links ]

22. Vanobbergen J, Martens L, Lesaffre E, Bogaerts K, Declerck D. Assessing risk indicators for dental Caries in the primary Dentition. Community Oral Dent Epidemiol 2001; 29: 424-434. [ Links ]

23. Dos Santos M, Dos Santos L, Francisco SB, Cury JA. Relationship among dental plaque composition, daily sugar exposure and caries in the primary dentition. Caries Res 2002; 36: 347-352. [ Links ]

text in

text in