Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versão impressa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.24 no.1 Medellín jul./dez. 2012

CASE REPORT

Clinical treatment of a patient with generalized advanced chronic periodontitis at the School of Dentistry of Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. A case report

Willer Leandro Rendón Osorio1; Isabel Cristina Guzmán Zuluaga2; Ingrid Ximena Torres Quiroz3; Leticia Botero Zuluaga4

1 Senior Dentistry Student, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia,

Medellín, Colombia

2 Dentist, Specialist in Periodontics, Universidad de Chile, Assistant

Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín,

Colombia

3 Dentist, Specialist in Oral Rehabilitation, CIEO Universidad Militar Nueva

Granada, Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia,

Medellín, Colombia

4 Dentist, Specialist in Comprehensive Dentistry of the Adult, Full

Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín,

Colombia

SUMBITTED: AUGUST 27/2012-ACCEPTED: SEPTEMBER 25/2012

Rendón WL, Guzmán IC, Torres IX, Botero L. Clinical treatment of a patient with generalized advanced chronic periodontitis at the School of Dentistry of Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. A case report. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 24(1): 151-167.

ABSTRACT

Periodontal disease affects the patient's health altering the form, function, and esthetics of the stomatognathic system and producing huge deterioration in the person's quality of life. This clinical case presents the comprehensive treatment of a 43-year-old male patient with generalized advanced chronic periodontitis including: non-surgical and surgical periodontal treatment and oral rehabilitation during a period of eighteen months by a senior undergraduate student and a group of professors specialized in periodontics and oral rehabilitation under the modality of teaching-social assistance at the School of Dentistry of Universidad de Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia).

Key words: chronic periodontitis, full mouth disinfection, non-surgical periodontal therapy, surgical periodontal therapy, removable partial prosthesis

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is one of the principal oral diseases among the adult population; its chronic form is the most common. This disease affects the structures of dental support and, if left untreated, it may cause generalized teeth loss and deteriorate the patient's general health as it is associated with systemic diseases.1, 2

Some risk factors may modify an individual's vulnerability or resistance to periodontal disease. These periodontitis risk factors have been identified: periodontal pathogen microorganisms, poor oral hygiene, diabetes and other systemic diseases associated to immunological dysfunction, tobacco smoking, age, sex, race, genetic predisposition, socioeconomic status, obesity, stress, immunosuppression, among others.3, 4

The main objective of periodontal therapy is to control and eliminate inflammation by suppressing subgingival periodontopathogenic flora; also, maintaining good oral hygiene by the patient is fundamental.5

The classical periodontal therapy includes scaling and root planing; however, more recent therapeutic approaches, such as total mouth disinfection and the use of systemic antibiotics, have modified classical therapies achieving better results in cases of aggressive periodontitis or advanced chronic periodontitis.6

Several studies have demonstrated that traditional non-periodontal therapy may control periodontal disease in most cases of chronic periodontitis; however, it has some limitations, such as the difficulty of properly instrument hard-to-reach areas to completely remove soft and hard deposits, especially the invasive microorganisms of soft tissues. Some scientific evidence indicate that besides accumulating at periodontal pockets periodontal pathogens dwell in other areas such as supragingival plaque, the tongue, the mucosa, saliva, and the tonsils; also, transmission and reinfection among these ecological niches may occur, as well as among individuals.5, 7-13

In cases in which deep residual periodontal pockets persist along with periodontopathogenic microbiota, bone defects, and muco-gingival defects after performing mechanical periodontal therapy, it is necessary then to proceed to surgical therapy in order to improve access and to create a favorable osseous and gingival morphology. Defects and bifurcation damages must be carefully evaluated as there is a big probability of a regenerative processes initiating in them.14-17

Once the patient recovers, a support treatment should start consisting on periodical scheduled follow-up appointments according to evolution over time, tissue response, and the patient's hygiene quality. This period is known as periodontal maintenance and is very important to periodontal health stability as it allows obtaining a significant change in the quality and quantity of subgingival bacterial flora by means of oral hygiene instruction, supra- and sub-gingival periodontal adjustment, and constant clinical and radiographic monitoring.5, 18, 19

It is important to bear in mind that due to dental loss suffered by most periodontitis patients, it is necessary to perform prosthetic treatment in order to restore patient's functionality and esthetics. The complexity of this rehabilitating treatment depends on the effects produced by the periodontal disease.

The objective of this article is to present the comprehensive treatment of a periodontal prosthetic patient providing dentistry students and professional dentists with some guidelines on the interdisciplinary treatment of a challenging case.

CASE REPORT

This was a 43 year old male patient, married, with a high school diploma, and socioeconomic status No 3 (medium). He is a freelance worker living in the city of Medellín. He sought dental attention on February 2011 at the School of Dentistry of Universidad de Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia. He admitted being asymptomatic but referred this as the reason for consulting: ''I was told I have periodontal problems and in my gums''.

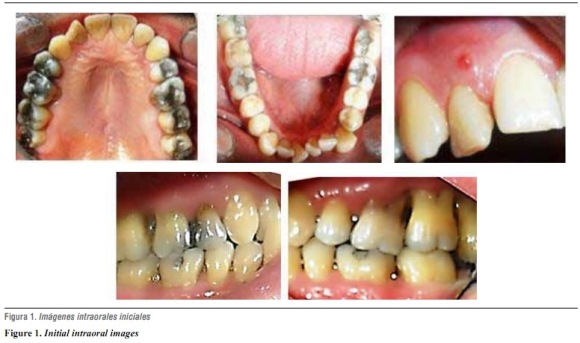

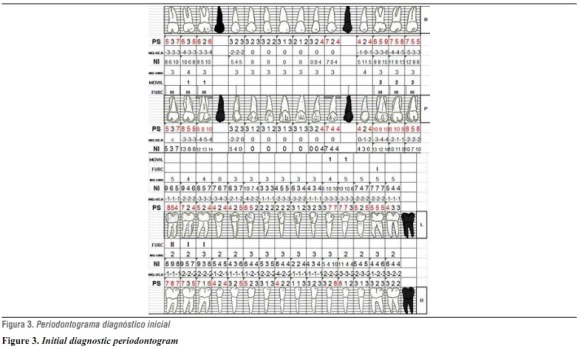

A complete clinical history was registered, and several diagnostic aids were performed, such as clinical photographs, periapical radiographic series figures 1, 2 y 3), and study models. The principal findings include: the patient is systemically healthy, with family history of periodontal disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and dental prosthesis; the functional analysis of the temporomandibular joint revealed a slight block by the end of oral opening followed by a dull noise and a sudden movement. The patient has had history of articular noise and a joint block on maximum opening. He admits brushing his teeth daily at least twice a day and not using dental floss very often. A fistulous tract was observed at the level of tooth 12 (figure 1), as well as soft and hard dentobacterial plaque, dental mobility degree 1 and 2 at 16, 17, 26, 27, 28, 33, and 34, gingival retractions with positive bleeding clinical indexes (30%), inflammation, suppuration, probing depth, and loss of clinical insertion. It is important to point out the presence of lower anterior dental crowding as a local risk factor that favors bacterial plaque accumulation20, 21 (figure 1). The radiographic analysis showed generalized bone loss in both vertical and horizontal directions, and a significant periapical lesion on tooth 12 (figura 2).

DIAGNOSIS

Systemic: healthy

Dental: occlusal active caries on 47, faulty dental restoration on 12, dental attrition on lower anterior teeth and abnormal teeth position (lower anterior crowding).

Pulpal: necrotic pulp on 12 with chronic suppurative apical periodontitis.22

Periodontal: generalized (84%) advanced chronic periodontitis with an average clinical insertion loss of 5.8 mm, bi- and trifurcation on 16, 17, 18, 26, 27, 28 (degree IIIc), 48 (degree IIb), 46, 47 (degree Ia) (figure 3),17, 23, 24 and secondary occlusal trauma.25

Occlusal: Class III malocclusion with malposition of teeth.

TMJ: subluxation26

PROGNOSIS

The general prognosis is poor due to chronic periodontal disease and abundant destruction of supporting tissue; also, the patient was a heavy smoker for almost ten years. The patient does not present systemic diseases, and quit smoking sixteen years ago.27

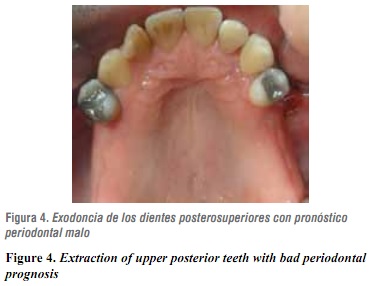

Individual periodontal prognosis is bad for teeth 16, 17, 18, 26, 27, and 28 because insertion loss has reached the root apex, with trifurcation degree III type c; tooth 28 does not have an opposing tooth. Individual prognosis is poor for teeth 23, 33, and 34 because bone loss has affected two thirds of dental root; it is also poor for tooth 12 due to necrotic pulp and extensive apical periodontitis, and for 46, 47, and 48 due to significant insertion loss and bifurcation degree II types a and b.27

The patient sought dental attention for the first time on February 22nd 2011 and he was immediately told about the importance of starting a comprehensive dental treatment. Once diagnosis and prognosis had been established, a treatment plan was designed on April 24th 2011 with approval by the patient who signed an informed consent before initiating treatment.

TREATMENT

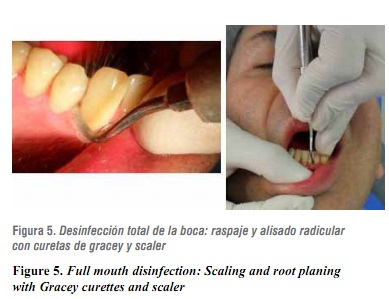

Several clinical procedures were performed during the hygienic phase in order to stop periodontal infection and to teach the patient how to maintain good oral hygiene; this included: patient's motivation and education on oral health, supragingival periodontal preparation with scalers and curettes, dental prophylaxis with toothbrush and prophylactic paste, simple extraction for teeth with bad periodontal prognosis: 16, 17, 18, 26, 27, 28 (figure 4), removal of active caries on 47, pulpal debriding and endodontics of tooth 12, subgingival periodontal preparation to entire mouth (total mouth disinfection)28 which included: non-surgical scaling and root planing with curettes and sonic-scaler machine to remove subgingival irritants and disorganize adhered and non-adhered bacterial flora.5, 29 (figure 5).

It also included mouth wash with emphasis on the back of the tongue and tonsils with a 0.12% digluconate chlorhexidine solution (Periogard) two times a day during 15 days, and application of 0.2% chlorhexidine gel (Dentagel) on periodontal pockets by means of subgingival irrigations two times a day.28

The process of scaling and root planing of the four quadrants was performed in less than twenty-four hours following the guidelines for total mouth disinfection suggested by Quirynen (1995).28 Due to the severity of the patient's periodontal disease (advanced) the prescription of systemic antibiotics was required as a complement to periodontal therapy.6, 10, 30

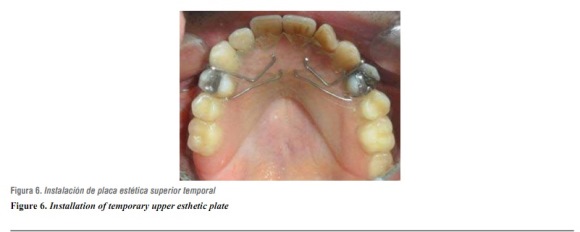

Amoxicillin in capsules of 500 mg was prescribed every 8 hours during 7 days because, according to scientific evidence,10 periodontal pathogens are sensible to this antibiotic. This hygienic phase finished with the installation of an upper esthetic plate due to the extraction of maxillary molars (figura 6).

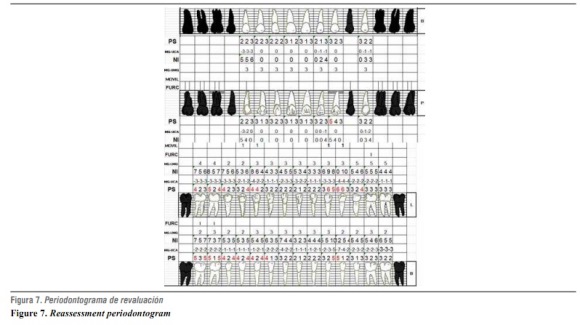

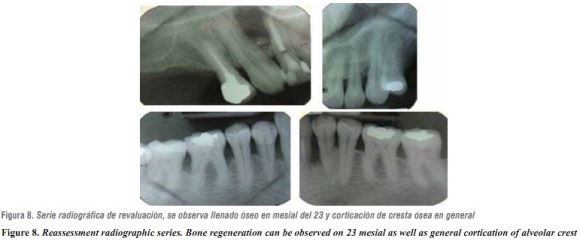

Reassessment was performed eight weeks after periodontal disinfection—the required period for healing of periodontal tissues—.29 This step included: evaluation of oral tissues, construction of a new periodontogram (figure 7), and completion of a new periapical radiographic series (January 16th 2012) (figure 8).

The results obtained so far were satisfactory: considerable reduction of inflammation and gingival bleeding, absence of suppuration, improvement of oral hygiene, reduction of periodontal probing, bone regeneration, and cortication of alveolar crest on affected areas.20

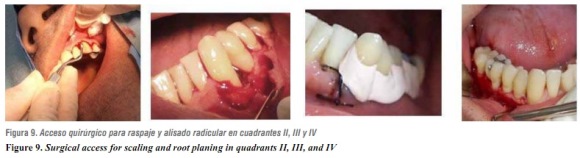

Based on these clinical and radiographic results, a new periodontal diagnosis was established: mild chronic periodontitis located on 23 and moderate chronic periodontitis located on 33, 34, 35 as well as on 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 y 48.23, 24 Treatment of this new condition included extraction of 48 due to persistent periodontal pocket larger than 5 mm; bifurcation degree IIb with no opposing teeth even after rehabilitation and occlusion on upper alveolar ridge.17, 27 The surgical periodontal phase was then planned and performed5, 14, 15, 31 for the rest of areas affected by periodontitis, in this manner: intra-sulcus incision, flap elevation, elimination of granulomatous tissue, scaling and planing with curettes and scaler, flap repositioning, atraumatic suture caliber 4/0 (Ethicon®) and periodontal dressing installation (Coe Pack®) (figure 9). AINEs was prescribed during three days as well as 0.12% chlorexidine (Periogard®).

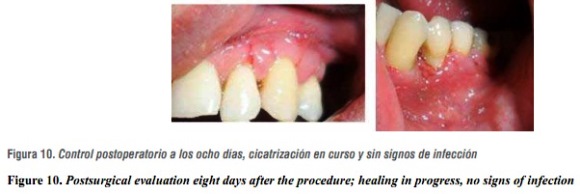

Postsurgical evaluation was performed eight days later; the periodontal suture was removed and healing process was observed; no signs of infection were found (figure 10).

Once periodontal healing was completed (eight weeks),29 new probing was performed and no periodontal pockets were found, nor other signs or symptoms of periodontal disease.

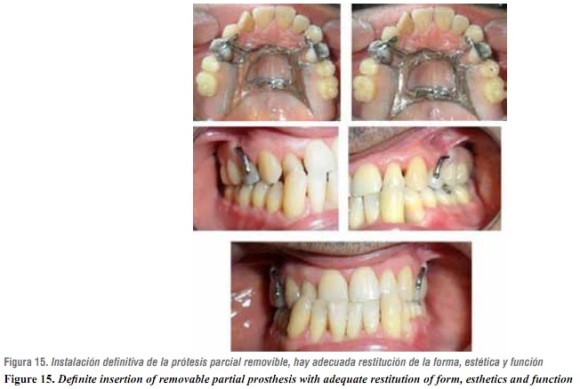

Once periodontitis had been controlled and maxillary edentulism classified as Kennedy class I (topographic classification of edentulism) (figure ), several prosthetic treatment options were suggested to replace missing teeth; these options ranged from using implants to adapting an acrylic metal removable partial prosthesis, but due to the patient's biological conditions, such as little maturation time of periodontal tissue,29 poor oral hygiene history, and scarce economic resources, the second alternative was chosen.

Type III plaster models were obtained, as well as occlusal records and tests on semi-adjustable articulator and parallelometer. Based on this analysis, a partially removable prosthesis with bilateral distal extension was planned; this required a careful design since characteristics of the residual ridge and base movement during its functioning would determine the occlusal efficacy of the prothesis.32

Also, both rigidity of the major connector and maximum coverage of residual ridges by the base of the prosthesis were analyzed in order to reduce the loads produced on abutment teeth.33, 34Designing of the upper prosthesis took into account retention, support and stability,35 so a larger connector was designed, with a combined anterior and posterior band and RPI system (occlusal rest, proximal guide plate, and approaching I bar clasp) on 14 and 24. Then the guide planes were impressed on the mouth, as well as the occlusal and cingular floors.

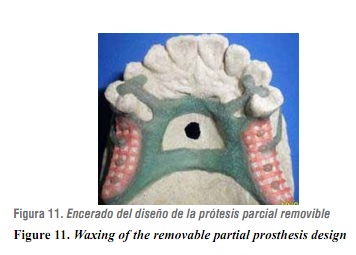

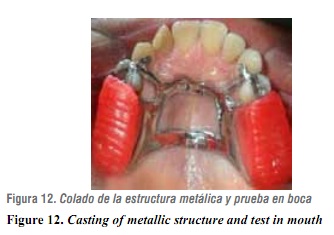

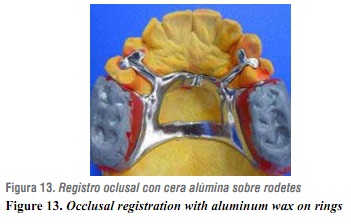

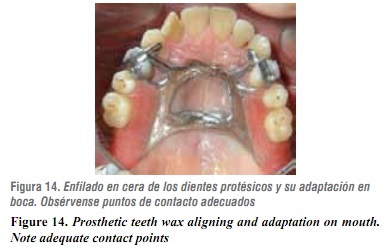

Later, the final impression was taken by using addition silicone. Next, the prosthesis design was verified with metal structure waxing (figure 11) and draining was performed by means of a cobaltchrome alloy.36 The metal structure was tried on the patient to verify it fitted well, and habitual occlusion was registered (figures 12 y 13).

Teeth alignment was then performed and tested on the patient (figure 14); acrylic was added on the structure and the patient's mouth was examined again. Satisfactory results were achieved in compliance with clinical criteria and patient's perception (figure 15). Finally, three follow-up appointments for prosthesis control were scheduled.

DISCUSSION

A critical part of periodontitis treatment consists on controlling and removing the irritant bacteria associated to the disease; this may be partially or totally achieved by means of non-surgical periodontal therapy5, 29 —a multifactorial treatment of periodontal inflammatory lesions—.29, 37Following the guidelines by Quirynen (1995)28, 38 and Cobb (2002).29

in our case the treatment team decided to perform non-surgical periodontal treatment taking into account: severity of the disease, patient's needs, and risk factors, trying to obtain the best possible results.

From a periodontal perspective, the clinical parameters, either individually or in combination, may fail to predict the disease activity in specific areas or to identify treatment response, except for the loss/gain changes in insertion degrees, measured in two different moments.21, 39

After the reassessment period of eight weeks, clinical parameters such as probing depth, clinical junction level, bleeding at probing, and the inflammatory clinical signs showed improvement as reported by different studies.

Bone loss interruption, as shown by the radiographic reassessment, as well as connective tissue reorganization, as proven by the clinical reassessment, are two other positive results.21

The use of a systemic antibiotic as a complement to periodontal therapy has been widely documented; it has been demonstrated that patients treated this way present better clinical results than the ones who did not receive a systemic antibiotic.40 The combination commonly used includes Amoxicillin® plus Metronidazole®, yielding satisfactory results;6 in this case we prescribed Amoxicillin alone three times a day during seven days, based on a study by Botero et al (2007)10 on a Colombian population in which the authors concluded that common periodontal pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. g.), Porphyromonas subespecies (P. sp.) and Prevotella intermedia (P. i) are highly sensitive to Amoxicillin, with an effectiveness that ranges between 70 and 86.9%; they also proved that these microorganisms are resistant to Metronidazole®.

However, prescribing a systemic antibiotic may bring some difficulties, such as treatment cost increase (according to the medicines used), pathogens' antibiotic resistance41 due to misuse, excess use or self-medication, and side effects associated to antibiotics use, such as pseudomembranous colitis.42

It is important to mention the strong relationship between tobacco smoking and periodontitis, since it is the most significant environmental risk factor that may modify not only periodontitis incidence but also its evolution.27, 43 Also, it may negatively alter treatment outcome due to a reduced immune response caused by vascular changes produced by the habit.44 Our patient was a heavy smoker for ten years, and although by the time of treatment he had already quit smoking for sixteen years, his habit may have altered aspects such as severity of periodontal destruction.

During the surgical phase, we considered necessary to apply surgical cement (Coe-pack®)after repositioning and suturing the flap, since it has been reported that this material provides the patient with more comfort during the post-operatory period. Also, it offers wound protection, enables a close flap-bone adaptation, and may prevent bleeding and formation of excessive granulation tissue.15

The periapical infection of tooth 12 (suppurative chronic apical periodontitis) improved as a consequence of the endodontic treatment; the fistulous tract disappeared as well as the remaining signs and symptoms of the lesion. Also, the radiographic evaluation showed that the apical lesion decreased in size, and although it still exists no clinical observations indicate its progression.45, 46 Following recommendations by the endodontics specialist, we decided to perform radiographic checkups for a year in order to evaluate whether apical surgery would be needed after that period.

Cobb (2002)29 maintains that periodontal tissues heal during six to eight weeks after periodontal treatment, and that they achieve maturation in a period of nine to twelve months. These postulates, plus the patient's oral hygiene history, led us to discard oral rehabilitation by means of dental implants.

The objectives of prosthetic treatment include restitution of posterior occlusal support to avoid bite collapse, with the help of a well-designed removable partial prosthesis (RPP), adequate orientation of occlusal forces, conservation of prosthetic abutments, and maintaining good oral hygiene,47 all of which are necessary for good treatment results and to provide patients with successful periodontal and prosthetic treatments. It is extremely important to design a personalized maintenance program for patients rehabilitated with RPP, according to their capacity to control oral hygiene, as well as to evaluate the activity of both periodontal disease and caries, alveolar ridge resorption, occlusal stability, and the conditions of RPP over time.48-51

As pointed out by Renvert & Persson (2004),19

it is critical to include the patient in the phase of periodontal maintenance or support treatment, consisting on periodical follow-up appointments scheduled according to the evolution over time and tissue response, and especially according to the quality of oral hygiene by the patient. In this case, the follow-up appointments will be scheduled every three months.

This last treatment phase is necessary for periodontal health stability, as it enables a significant change of the quality and quantity of subgingival bacteria by means of instruction on oral hygiene, supragingival periodontal adjustment, and clinical monitoring.5

CONCLUSION

Success on the periodontal and prosthetic treatment of this patient responds to several key elements: patient's education and active participation in his treatment, design of a comprehensive treatment plan based on scientific and clinical concepts that have been verified by previous studies, and its implementation by an interdisciplinary team, under a teaching-community outreach model that allows complex dental treatments at lower costs for the community.

The comprehensive treatment of patients who have lost their teeth due to periodontitis includes rehabilitation by means of dental prosthesis in order to restitute their teeth's form, function and appearance, thus improving patients' quality of life.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Leticia Botero Zuluaga

Facultad de Odontología

Universidad de Antioquia. Colombia

Email address: lbotero@odontologia.udea.edu.co

REFERENCES

1. López R, Oyarzún M, Naranjo C, Cumsille F, Ortiz M, Baelum V. Coronary heart disease and periodontitis-a case control study in Chilean adults. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29(5): 468-473. [ Links ]

2. Abnet CC, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Mark SD. Tooth loss is associated with increased risk of total death, and death from upper gastrointestinal cancer, heart disease, and stroke in a Chinese population-based cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2005; 34: 467-474. [ Links ]

3. Armitage GC, Offenbacher S. Consensus report on periodontal diseases: epidemiology and diagnosis. Ann Periodontology 1996; 1: 216-222. [ Links ]

4. Rioboo Crespo M, Bascones A. Factores de riesgo de la enfermedad periodontal: factores genéticos. Av Periodon Implantol 2005; 17(2): 69-77. [ Links ]

5. Botero L, Botero A, Bedoya JS, Guzmán IC. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2012; 23(2): 150-158. [ Links ]

6. Cionca N, Giannopoulou C, Ugolotti G, Mombelli A. Amoxicillin and metronidazole as an adjunct to full mouth scaling and root planing of chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2009; 80: 364-371. [ Links ]

7. Heitz-Mayfield H, Trombelli L, Heitz F, Needleman I, Moles D. A systematic review of the effect of surgical debridement vs. non-surgical debridement for the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2002: 29 (supl 3): 92-102. [ Links ]

8. Mombelli A, Schmid B, Rutar A, Lang NP. Persistence patterns of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotellaintermedia/nigrescens, and Actinobacillusactinomyetemcomitans after mechanical therapy of periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2000; 71(1): 14-21. [ Links ]

9. Slots J, Slots H. Bacterial and viral pathogens in saliva: disease relationship and infectious risk. Periodontol 2000 2011; 55(1): 48-69. [ Links ]

10. Botero A, Alvear FS, Vélez ME, Botero L, Velásquez H. Evaluación de los enfoques terapéuticos para las varias formas de enfermedad periodontal. Parte II: aspectos microbiológicos. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2007; 19(1): 6-20. [ Links ]

12. Doungudomdacha S, Rawlinson A, Walsh T, Douglas C. Effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on clinical parameters and the numbers of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotellaintermedia and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans at adult periodontitis sites. J Clin Periodontol 2001; 28: 437-445. [ Links ]

13. Tatsuji N, Takeyoshi K. Microbial etiology of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2004; 36: 14-26. [ Links ]

14. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Ximenez LA, Feres M, Mager D. Ecological considerations in the treatment of Actinobacillusactinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis periodontal infections. Periodontol 2000 1999; 20: 341-362. [ Links ]

15. Carranza FA. Técnica de colgajo para el tratamiento de bolsas. En: Carranza FA. Periodontología clínica, 10.a ed. México: McGraw-Hill; 2010. p. 134-169. [ Links ]

16. Lindhe J, Lang N, Karring T, Berglundh T, Giannobile W, Sanz M. Cirugía periodontal: procedimientos de acceso. En: Periodontología clínica e implantología odontológica. 5.a ed. Vol. II. Buenos Aires: Panamericana; 2009. [ Links ]

17. Silvestri M, Rasperini G, Milani S. 120 Infrabony defects treated with regenerative therapy: long-term results. J Periodontol 2010; 82(5): 668-675. [ Links ]

18. Kinaia BM, Steiger J, Neely AL, Shah M, Bhola M. Treatment of class II molar furcation involvement: metaanalyses of reentry results. J Periodontol 2011; 82(3): 413-428. [ Links ]

19. Croft LK, Nunn ME, Crawford LC, Holbrook TE, McGuire MK, Kerger MM et al. Patient preference for ultrasonic or hand instruments in periodontal maintenance. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2003; 23(6): 567-573. [ Links ]

20. Renvert S, Persson G. Supportive periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000 2004; 36: 179-195. [ Links ]

21. Renvert S, Persson GR. A systematic review on the use of residual probing depth, bleeding on probing and furcation status following initial periodontal therapy to predict further attachment and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29 (supl 3): 82-89. [ Links ]

22. Botero A, Alvear FS, Vélez ME, Botero L, Velásquez H. Evaluación de los enfoques terapéuticos para las varias formas de enfermedad periodontal. Parte I: aspectos clínicos. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2007; 18(2): 6-16. [ Links ]

23. Berman L, Hartwell G. Diagnóstico. En: Cohen S, Hargraves K. Vías de la pulpa. 9.a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier Mosby; 2008. [ Links ]

24. Armitage G. American Academy of Periodontology. International workshop for a classification of periodontal disease and condition. Ann Periodontol 1999; 4: 1-6. [ Links ]

25. Armitage G. Diagnóstico y clasificación de las enfermedades periodontales. Periodontol 2000 2005; 9: 9-21. [ Links ]

26. Lindhe J, Lang N, Karring T, Berglundh T, Giannobile W, Sanz M. Trauma oclusal: tejidos periodontales. En: Periodontología clínica e implantología odontológica. 5.a ed. Vol. I. Buenos Aires: Panamericana; 2009. [ Links ]

27. Okeson J. Signos y síntomas de los trastornos temporomandibulares. En: Tratamiento de oclusión y afecciones temporomandibulares. 6.a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier Mosby; 2008. [ Links ]

28. Botero L, Alvear FS, Vélez ME. Factores del pronóstico en periodoncia. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2008; 19(2): 69-79. [ Links ]

29. Quirynen M. Bollen C. Full-vs. Partial-muoth disinfection in the treatment of periodontal infections: short-term clinical and microbiological observations. J Dent Res 1995; 74(8): 1459-1466. [ Links ]

30. Cobb CM. Clinical significance of non-surgical periodontal therapy; an evidence-based perspective of scaling a root planing. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29 (supl 2): 6-16. [ Links ]

31. Guzmán IC, Grisales H, Ardila CM. Adjunctive systemic administration of moxifloxacin versus ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole in the treatment of chronic periodontitis harboring gram-negative enteric rods: microbiological and clinical effects. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2011; 23(1): 92-110. [ Links ]

32. Fabrizi S, Barbieri Petrelli G, Vignoletti F, Bascones- Martínez A. Tratamiento quirúrgico vs. terapia periodontal básica: estudios longitudinales en periodoncia clínica. Av Periodon Implantol 2007; 19(3): 161-175. [ Links ]

33. Giraldo OL. Cómo evitar fracasos en la prótesis parcial removible. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2008; 19(2): 80-88. [ Links ]

34. Piwowarczyk A, Köhler KC, Bender R, Büchler A, Lauer HC, Ottl P. Prognosis for abutment teeth of removable dentures: a retrospective study. J Prosthodont 2007; 16: 377-382. [ Links ]

35. Nickenig HJ, Spiekermann H, Wichmann M, Andreas SK, Eitner S. Survival and complication rates of combined toothimplant- supported fixed and removable partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont 2008; 21: 131-137. [ Links ]

36. Kaiser F. PPR: no laboratório, en el laboratorio. 3.a ed. São Paulo: Quintessence; 2010. [ Links ]

37. Wataha JC. Biocompatibility of dental casting alloys: a review. J Prost Dent 2000; 83(2): 223-233. [ Links ]

38. Caffesse RG, Mota LF, Morrson EC. The rational for periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000 1995; 9: 7-13. [ Links ]

39. Quirynen M, Bollen CML. The influence of surface roughness and surface-free energy on supra and subgingival plaque formation in man. A review of the literature. J Clin Periodontol 1995; 22: 1-14. [ Links ]

40. Lang NP, Adler R, Joss A, Nyman S. Absence of bleeding on probing an indicator of periodontal stability. J Clin Periodontol 1990; 17: 714-721. [ Links ]

41. Herrera D, Sanz M, Jepsen S, Needleman I, Roldán S. A systematic review on the effect of systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29 (supl 3): 136-159. [ Links ]

42. Kleinfelder JW, Müller RF, Lange DE. Antibiotic susceptibility of putative periodontal pathogens in advanced periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol 1999; 26: 347-351. [ Links ]

43. Orellana A, Salazar E. Colitis pseudomembranosa asociada al uso de antibióticos. Acta Odontol Venez 2009; 47: 1-5. [ Links ]

44. Kinane D, Peterson M, Stathopoulou PG. Factores ambientales y otros factores que modifican las enfermedades periodontales. Periodontol 2000 2007; 16: 107-119. [ Links ]

45. Pahkla E, Koppel T, Naaber P, Saag M, Loivukene K. The efficacy of non-surgical and systemic antibiotic treatment on smoking and non-smoking periodontitis patients. Stomatologija 2006; 8: 116-121. [ Links ]

46. Nair P. Fisiopatología de la periodontitis apical primaria. En: Cohen S, Hargraves K. Vías de la pulpa. 9.a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier Mosby; 2008. [ Links ]

47. Johnson B, Witherspoon D. Cirugía perirradicular. En: Cohen S, Hargraves K. Vías de la pulpa. 9.a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier Mosby; 2008. [ Links ]

48. Zlatariæ DK, Celebiæ A, Valentiæ-Peruzoviæ M, Jerolimov V, Panduriæ J. A survey of treatment outcomes with removable partial dentures. J Oral Rehabil 2003; 30: 847-54. [ Links ]

49. Vanzeveren C, D'Hoore W, Bercy P. Influence of removable partial denture on periodontal indices and microbiological status. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29(3): 232-239. [ Links ]

50. Zlataric DK, Celebic A, Valentic Peruzovic M. The effect of removable partial dentures on periodontal health of abutment and non-abutment teeth. J Periodontol. 2002; 73(2): 137-144. [ Links ]

51. Yeung AL, Lo EC, Chow TW, Clark RK. Oral health status of patients 5-6 years after placement of cobaltchromium removable partial dentures. J Oral Rehabil 2000; 27: 183-189. [ Links ]

52. Yeung AL, Lo EC, Clark RK, Chow TW. Usage and status of cobalt-chromium removable partial dentures 5-6 years after placement. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29: 127-132. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em