Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versão impressa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.25 no.1 Medellín jul./dez. 2013

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

A REVIEW OF THE UTO-AZTECAN PREMOLAR TRAIT IN SOUTH AMERICA AND ITS PRESENSE IN COLOMBIA

Carlos David Rodríguez-Flórez1

1 Research Grant Holder, Post-Doctoral Scholarship Program, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. Associate researcher, Anthropology Lectures, School of Exact, Physical, and Natural Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina. E-mail address: cadavid98@hotmail.com

SUMBITTED: MAY 22/2012-ACCEPTED: AUGUST 27/2013

Rodríguez-Flórez CD. A review of the Uto-Aztecan premolar trait in South America and its presence in Colombia. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2013; 25(1): 147-157.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the so-called Uto-Aztecan premolar (hereinafter UAP) or distal-sagittal crest of upper premolars is a rare morphologic trait that appears in the first premolars of American Indian groups only. It is described as the presence of a pronounced crest extending from the tip of the buccal cusp (paracone) towards the distal-occlusal edge, almost reaching the sagittal sulcus. The objective of this study was to describe the presence of UAP in South America and its relation with Colombian indigenous populations. METHODS: A total of 495 individuals recorded in the literature were collected. Conventional descriptive statistics was used to observe asymmetry and atypical variables. Comparisons were made using Smith's mean measure of divergence. RESULTS: The spreading of this trait in South America might have been due to interactions between the groups represented by two biological components observed in the calculated matrix. DISCUSSION: The Pacific Ocean coast and the valleys that connect the Andean and Amazonian regions coupled with their main rivers should have played a role in the rapid spread of this trait in samples located as far apart as Minas Gerais (Brazil) and Punta Teatinos (Chile). CONCLUSIONS: UAP is present in Colombia since about 3000 BP (before present). This trait should be evaluated in mestizo groups.

Key words: sinodonts, Uto-Aztecan premolar, dental non-metric traits, Amerindians, South America, Colombia

INTRODUCTION

The so-called Uto-Aztecan premolar (hereinafter UAP) or distal-sagittal crest of upper premolars is a rare morphologic trait that appears in the first premolars of American Indian groups only. In dental anthropology, it is still debated whether this feature is unique to American Indian populations or whether it comes from Asia, as some data on the presence of this trait in prehistoric populations of Mongolia and Siberia have been recently reported by Johnson et al (in 2011).1

The systematic description of this trait is attributed to Morris et al in 1978.2 A few years later, this feature was included in the Asudas (Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System).3

UAP is described as the presence of a pronounced crest extending from the tip of the buccal cusp (paracone) towards the distal-occlusal ridge, almost reaching the sagittal sulcus.3 Some authors also believe that this may be the same trait characterized by buccal-distal torsion of the paracone (premolar buccal cusp) in the opposite direction to its apex, creating a hole or a deep sulcus on the distal portion of the buccal surface.4

From a functional perspective, the presence of such morphologies in human dental crowns is associated with structural strengthening of the occlusal enamel portion caused by strong masticatory forces in populations of pre-ceramic hunters and gatherers.5

Assuming polygenic inheritance, UAP is caused by the interaction of an unknown number of genes from different loci that connect with environmental factors to produce the gradual morphological expression of the trait. Several genes contribute in a differential and additive manner to the phenotypic variation of this trait.6 Previous studies have established that UAP is inherited, not directly associated with the X chromosome, and that it responds to a polygenic inheritance model—possibly an autosomal recessive one.7

The presence of bilateral asymmetry in the morphological manifestation of this trait (appearing on one side of the dental arch only) may be interpreted as the result of instability in the normal development of biological shapes.8 UAP's unilateral expression may be attributed to the environmental influence on a particular group of genes which produce this trait, as observed in other features of the upper dental arch such as Carabelli's trait and shovel-shaped teeth in other American and Asian populations mainly. Previous bilateral asymmetry studies on hereditary dental traits of a similar nature in pre-Hispanic samples from Colombia9 and Argentina10 show that the bilateral expression of such traits depends in part on isolation. The greater the geographic isolation the smaller the bilateral asymmetry, i.e., the traits almost always appears on both sides of the dental arch. Conversely, the smaller the geographic isolation, the greater the unilateral expression of traits. Molto's index shows that Carabelli's trait's bilateral symmetry is lower in Argentinian pre-Hispanic samples (3%) than in Colombian pre-Hispanic samples (41%). Similar values are found in shovel-shaped trait (Argentinian samples = 0%, Colombian samples = 8%). This happens because the exchange and communication processes that facilitate gene flow among societies are limited by larger geographical distances between the groups examined in Argentina than in Colombia during pre-Hispanic times.

In human populations, environmental factors are usually associated with the social behaviors that influence the favorable conditions for the expression of this kind of dental traits (gene exchange). Thus, one can understand that the asymmetry of a morphological trait of this kind is due to miscegenation processes among groups. These considerations are taken into account because the reports usually describe UAP as being unilateral.

The objective of this study is to gather information about the presence of this trait in South America in general and in Colombia in particular in order to make comparisons and to establish population trends that allow understanding its origin and the process of genetic drift in the continent. The importance of this study lies in its contribution of comparative information to the debate about the origins and biological relationships of ancient human groups from the Northern Andes region, especially in terms of its connection with other regions where this trait has been found, such as Mesoamerica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

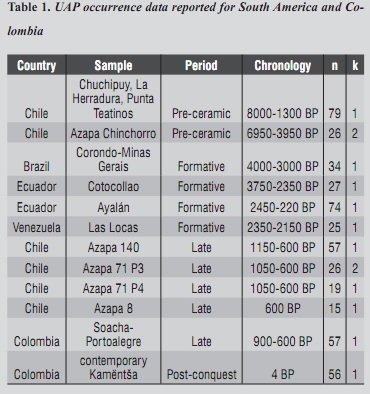

The presence of UAP in South America is very old. It can be traced back to the Pre-ceramic period (between 12,000 and 6,000 years BP), although there are chronological uncertainties in samples from Chichipuy, La Herradura, and Punta Teatinos in Chile as they are part of a very extensive period of 6300 years (8000-1300 BP) covering the Pre-ceramic and the Formative periods in the region. These archaeological samples indicate the oldest presence of this trait in South America with a very low prevalence (1.26%). The same happens with Azapa-Chinchorro samples in Chile, with a timeline between 6950- 3950 BP, showing a very low frequency although it is higher than the one mentioned above (7.6 %).

Regarding the Formative period between 6000 and 1500 BP, both the presence of this trait and its geographical distribution seem to increase. In the Andean region, it appears further north in the Andes of Ecuador and continues exhibiting low frequency in the samples from Ayalán (1.3%) and Cotocollao (3.7%). In the northernmost area of the Andes in Venezuela, UAP appears in samples of Las Locas (4%). In the Amazon jungle, in southeastern Brazil, there is a similar prevalence rate in samples from Corondo-Minas Gerais (2.9%).

During the Late Period, between the years 1500 and 500 BP, this trait appears in populations of the coastal and northern Andean region of Chile and the Andes of Colombia. In Chile, the samples show an equally low percentage. By grouping the frequencies of all samples from Azapa Valley (Azapa 140, 71 P3, 71 P4, 8) one can note that the presence of this trait does not exceed 4.2%. Out of a total of 439 individuals tested in South America, only 13 had the trait (2.9%).1, 7

The presence of UAP in Colombia is very low, taking into account that at least 700 individuals of different periods have been examined by the author in different parts of the country. In the pre-Hispanic period, the presence of this trait was reported in an individual from the Soacha-Portoalegre bone collection. This collection from the Muisca culture was analyzed in 2010, reporting a frequency of 2.7%.7 Further analysis allowed the author to consider the frequency reported in 2010 as somewhat overestimated, since the total number of analyzed individuals with premolars was not initially 37 but 57. Therefore, the correct frequency of this trait in pre-Hispanic Colombia is 1.7%.11 Despite this adjustment, the percentage does not vary significantly, and the presence of this feature in the country is still very close to the average in South America (2.9%).

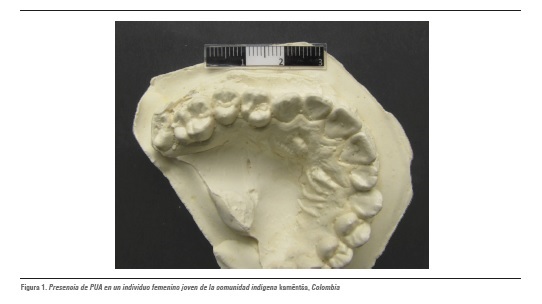

In the case of contemporary indigenous groups (50 years to the present), this trait has been reported only once in a sample of children from the Kamëntša indigenous community in the department of Putumayo.12 In this sample, the frequency of UAP remains low (1.8%) and very similar to the pre-Hispanic samples from the Muisca culture. Figure 1 shows in detail the presence of this trait described from the disto-sagittal crest in the paracone of the upper first premolar. The photo was taken on a plaster replica of the maxilla of a Kamëntša girl from the department of Putumayo, Colombia, in 2009. Table 1 displays the data reported for South America, including Colombia.

RESULTS

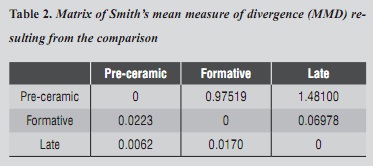

A previous analysis established a matrix of divergence among periods of cultural development in South America including samples with UAP.11 The multivariate comparison suggests differences between the periods analyzed in South America. The Formative and Late periods appear closer to each other, and the Pre-ceramic shows a greater difference (table 2).

In table 2 values above the zeros indicate the estimated MMD, and values in boxes below the zeros indicate two standard deviations. A quick observation suggests that although all the possible comparisons show significant differences, the values between the pre-ceramic and the other groups demonstrate a greater biological distance. The biological variation distribution of a trait as special as UAP during a time span covering three periods of cultural development in the continent is explained by the comparison among periods. Two biological components may be observed: 1) an early component for the Pre-ceramic period, and 2) a component that gathers samples from the Formative and the Late.

On the other hand, the two components identified in the comparison may correspond to scatter foci of UAP trait in South America, although it is too early to assert a hypothesis of Hispanic populations' diaspora using only one morphological feature.

DISCUSSION

From a chronological point of view, the hypothesis of UAP's pre-ceramic origins7 cannot be verified in this study, but it cannot be totally rejected either since its verification has been limited to pre-ceramic series collected and analyzed up to this time not exceeding an intermediate date (8000 years BP) with a margin of uncertainty on the dates given to these samples (Chichipuy, La Herradura and Punta Teatinos in Chile). However, the hypothesis on a diaspora pattern from North America to South America is accepted for now,2, 7 although it should be taken with some precaution, since the presence of this trait may indicate even more accurate geographical limits of their origins in Northwestern Mesoamerica.

Accordingly, the dispersion of this trait in South America might have been due to interaction between the groups represented by both components. The dispersion pattern is not clear, but the Pacific coast and the valleys that connect the Andes and the Amazon along with their main rivers should have played a pivotal role in the rapid spread of this trait in samples as far apart as Minas Gerais (Brazil) and Punta Teatinos (Chile). A model that explains UAP's dispersion process in early pre-ceramic times is not necessarily the most appropriate.

A scenario of late Pre-ceramic (7000-6000 BP) and early Formative (6000-4000 BP), both being part of a Middle Holocene in which the valleys and major rivers communicated the Andes and the Amazonia has already been shown by archaeological evidence. Meggers and Evans13 mention migration processes from the Andes to the Colombian Amazon dispersing the first ceramic technologies. Another view14 suggests that new ceramic technologies and cultural adaptation strategies may have occurred in the opposite direction from the central Amazonia to the Andes. In both cases, the models are supported with chronological evidences in the early Formative period. Inter-Andean alleys communicating the Andes and the Amazonia such as the Valley of Sibundoy represented by the Kamëntša community samples, and major nearby rivers such as Caquetá and Putumayo which are directly connected with the Amazon River, are considered geographical reasons for establishing such connections between past societies. The ceramic similarities among formative societies of the Andes and the Amazonia, as well as the presence of cassava (Manihot carthagenensis) close to 6000 BP, provide further support to this approach.15 Similarly, the presence of UAP in formative samples from Venezuela16 may be explained by the same expansive process.

Analyses of the archaeological information of the area close to the Kamëntša community show that the oldest pre-ceramic site found so far on the Andean side of southern Colombia is San Isidro in the Valley of Popayán (department of Cauca) dated 10,000 BP.17 On the Amazon, the pre-ceramic site closest to Valle de Sibundoy is Peña Roja (high Caquetá) dated 9,100 BP.18 A direct relationship between these archaeological findings and the Kamëntša community cannot be established, but it is possible to suggest a scenario of multidirectional movements between the Andes and the Amazon, partially accepted for southern Colombia.19

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we may suggest that the UAP is a dental morphological trait that shows the relationship between two biological components associated with periods of cultural development in America. Although its dispersion pattern and chronological origin are not entirely clear, we propose a scenario framed in the Middle Holocene (between 7000 and 3000 BP grouping societies from the late Pre-ceramic and the early Formative) to explain its origin and possible dispersal routes towards South America, suggesting origins in Northwestern Mesoamerica or its probable dispersion in this area. This process must have been associated with cultural changes in the production of new technologies such as ceramics, large-scale cultivation, and economic exchange between the Andes the Amazonia and the Pacific Coast in Central America.

Finally, it is important to note that this is a latent morphological trait, which is still evident in today's indigenous groups such as Kamëntša. Its presence in mixed populations has not yet been documented, which inspires new research perspectives on its presence and manifestation in contemporary human groups' permanent dentition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To Dr. Carmen Dussán Luberth from the Department of Mathematics and Physics at Universidad de Caldas for her cooperation and enthusiasm in the different stages of this project. I owe special thanks to the entire community and the Cabildo Kamentsa Biya of Sibundoy. Thanks to my anthropology students who helped me in this process from the beginning. To the Anthropology student Lidia del Pilar Miticanoy and her family for their dedication, patience, and enthusiasm in acquiring dental samples, and to anthropologist Marcela Ospina and archaeologist Omar Peña for their assistance in photography and databases. To anthropologist Alfredo Coppa, from the Università di Roma "La Sapienza" and dentist David Gutiérrez from Universidad Antonio Nariño, for checking the samples that make up this study. To anthropologist Heather Edgar from Ohio University for her help in the literature. To all of them, my sincere thanks.

REFERENCES

1. Johnson KM, Stojanowsky CM, Miyar KOD, Doran GH, Ricklis RA. Brief Communication: new evidence on the spatiotemporal distribution and evolution of the Uto-Aztecan premolar. Am J Phys Anthropol 2011; 146: 474-480. [ Links ]

2. Morris DH, Huges SG, Dahlberg AA. The Uto-Aztecan Premolar: the anthropology of a dental trait. En: Butler P, Joysey KA, eds. Development, function, and evolution of teeth. London: Academic Press; 1978. p. 69-79. [ Links ]

3. Turner CG, Nichol C, Scott GR. Scoring procedures for key morphological traits of the permanent dentition: The Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System. En: Kelley M, Larsen CS, eds. Advances in dental anthropology. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1991; p. 13-31. [ Links ]

4. Johnston CA, Sciulli PW. Technical note: Uto-Aztecan premolars in Ohio Valley populations. Am J Phys Anthropol 1996; 100: 293-294. [ Links ]

5. Mizoguchi Y. Shovelling: a statistical analysis of its morphology. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 1985. [ Links ]

6. Lauc T, Rudan P, Rudan I. Campbell H. Effect of Inbreeding and endogamy on occlusal traits in human isolate. Dentofacial Orthop 2003; 30: 301-308. [ Links ]

7. Delgado ME, Scott RG, Turner CG. The Uto-Aztecan Premolar among North and South Amerindians: geographic variation and genetics. Am J Phys Anthropol 2010; 143: 570-578. [ Links ]

8. Palmer AR, Strobeck C. Fluctuating asymmetry analyses revisited. En: Polak M, Editor. Development instability: causes and consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. p. 279-319. [ Links ]

9. Rodríguez-Flórez CD, Colantonio SE. Importance of bilateral asymmetry analysis in archaeological samples: the case of six pre-conquest samples from Colombia, South America. Anthropologie: Int J Sci Man 2008; 46(1): 9-13. [ Links ]

10. Bollini GA, Rodríguez-Flórez CD, Colantonio SE. Bilateral asymmetry in permanent dentition of 13 pre-conquest samples from Argentina, South America. HOMO J Comp Hum Biol 2009; 60(2): 127-137. [ Links ]

11. Rodríguez-Flórez CD. Distancias biológicas entre poblaciones prehispánicas de Colombia usando rasgos no métricos de la dentición permanente. [Tesis de doctorado] Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; 2012. [ Links ]

12. Rodríguez-Flórez CD. Occurrence of Uto-Aztecan premolar trait in a Colombian Amerindian population. HOMO J Comp Hum Biol 2012; 63: 396-403. [ Links ]

13. Meggers B, Evans C. Lowland South America and the Antilles. En: Jennings JD, editor. Ancient South Americans. San Francisco: Freeman; 1983; p. 287-335. [ Links ]

14. Lathrap DW. Spinden revisited, or a unitary model for the emergence of agriculture in the New World. En: Reed CA, editor. Origins of agriculture, La Haya: Mouton; 1977. p. 713-750. [ Links ]

15. Reichel-Dolmatoff G. Arqueología de Colombia. Bogotá: Presidencia de la República; 1997. [ Links ]

16. Reyes G, Padilla A, Palacios M, Bonomie J, Jordana X, García C. Posible presencia de rasgo dental "Premolar Uto-Azteca" en un cráneo de época prehispánica (siglo II a. C. a siglo IV d. C.), cementerio de Las Locas, Quibor (Estado de Lara, Venezuela). Boletin Antropol 2008; 72: 53-85. [ Links ]

17. Gnecco C. Ocupación temprana de bosques tropicales de montaña. Popayán: Universidad del Cauca; 2000. [ Links ]

18. Cavelier I, Mora S. Ámbito y ocupaciones tempranas de la América tropical. Bogotá: Fundación Erigaie, Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia; 1995. [ Links ]

19. Aceituno FJ, Loaiza N. Domesticación del bosque en el Cauca medio colombiano entre el Pleistoceno final y el Holoceno medio. Oxford: Archaeopress; 2007; S1654. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em