Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versión impresa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.25 no.2 Medellín ene./jun. 2014

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

BARRIERS TO DENTAL CARE ACCESS DURING EARLY CHILDHOOD. MEDELLÍN, 20071

Cielo Astrid Quintero Valencia2; Diana Patricia Robledo Bermúdez2; Alejandro Vásquez Hernández2; Oriana Delgado Restrepo2; Ángela María Franco Cortés3

1 Article derived from a research project conducted as partial requirement to qualify for the title of dental practitioner of all the co-authors. Research funded by own source

2 Dentists, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail addresses: cieloa@gmail.com cieloa@msn.com

3 Dentist, Magister in Epidemiology, Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. Email: franco.angelamaria@gmail.com

SUBMITTED: NOVEMBER 22/2011-APPROVED: AUGUST 13/2013

Quintero CA, Robledo DP, Vásquez A, Delgado O, Franco ÁM. Barriers to dental care access during early childhood. Medellín, 2007. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2014; 25(2):

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: in health systems, access refers to the organization of services to ensure entry into the system and treatment continuity. The objective of this study was to identify dental care access barriers in children under the age of six from the experience reported by mothers and caregivers. METHODS: this was a descriptive study based on an individual semi-structured interview to 11 community mothers (caregivers) and group interviews with 37 biological mothers, of whom 20 participated in a second individual interview because they had attended dental consultation for their children in the past. RESULTS: community mothers are important in identifying children's oral problems but they consider that oral care demands are a responsibility of parents. Mothers value their children's oral health but they do not demand health care due to the fear of a traumatic situation. Health institutions encourage health care demands at more advanced ages. Access to services is even harder for SISBEN members. CONCLUSSION: during early childhood, children of lower socioeconomic levels face multiple barriers to dental care access. Even health insurance fails to guarantee access. The most frequent barriers are of economic nature, but there are also cultural barriers and those related to the system's organization, such as children's short age, often used by mothers and institutions as an excuse to avoid requesting or providing timely care.

Key words: health services accessibility, children's dental care, dental health services.

INTRODUCTION

Access to care services has been considered as a variable to measure health inequities. Scholars such as Aday and Andersen define access as "the dimensions that describe a population's real and potential entry to the system of health services provision".1 In other words, access to health systems is an element closely related to the organization of services, not only to ensure entry to such services but also treatment continuity, making it a multi-dimensional category. They define potential access as the possibility of obtaining attention in terms of supply (institutions) and demand (users), and real access as the effective use of services and patients' satisfaction.1

In Colombia, the National Policy of Health Services Provision2 defines health services accessibility as "the condition that links the population in need of health services with the service provision system". This relationship is determined by three factors: a) users' ability to seek and obtain care; b) type and form of service organization to provide citizens with timely and comprehensive attention, and c) relations established among the population, insurers, local authorities and health service providers.

It follows then that in health care access we may identify five dimensions that generate either opportunities or barriers, namely: the political-legal dimension, in terms of the way each country regulates care and health rights; the economic dimension, in terms of users' purchase capacity, costs to reach the places where care is provided, and the costs of service provision itself; the geographic dimension, related to location of health care providers, as well as distance, transportation facilities, and topographic conditions; the cultural dimension, related to the set of values, attitudes, knowledge, beliefs, and practices that make up the population's behavior towards the use of services, and the organizational dimension, associated to locative, administrative, and information conditions of the institutions in charge of managing or providing services.

Additionally, in November of 2006, Colombia approved the Childhood and Adolescence Code (1098 Act of 2006)3 with the objective of "guaranteeing full and harmonious development of children and adolescents so that they grow up in the bosom of the family and the community, in a supporting environment with happiness and love". With the approval of this code, the country commits to the protection of the younger population, usually vulnerable and exposed to many threats that originate in a pathological environment that has ignored that they are subjects of law.

Article 17 of this code states that "children and adolescents have the right to a good quality of life and a healthy environment with dignity and the possibility of enjoying all of their rights in a prevalent manner […] This right implies the creation of conditions that from the time of conception ensure care, protection, a nutritious and balanced diet, and access to the services of health, education, adequate clothing, recreation, and safe housing equipped with essential utilities in a healthy environment". Likewise, article 27 enshrines the right to Comprehensive Health, stating that "no hospital, clinic, health center or any other health service provider, either public or private, may refuse to attend a child that requires health care".

Specifically, in the case of children's access to dental care services, globally available data show that school-age children are the ones who more often access regular dental checkups, possibly due to the facility to recruit them through active search mechanisms and because of being an institutionalized population. In the case of younger kids (under 6 years), it has been noted that in addition to economic barriers, common in all age groups, cultural barriers, rising from a poor appraisal of oral health in the first years of life, as well as functional barriers, linked to an organization of services that perceives children as "uneconomic" users, make access more difficult to children, especially in lower socioeconomic levels.4-7

The purpose of this study was to identify barriers to dental care access in children under six years of age living in the city of Medellín, through responses to interviews with their mothers and caregivers.

METHODS

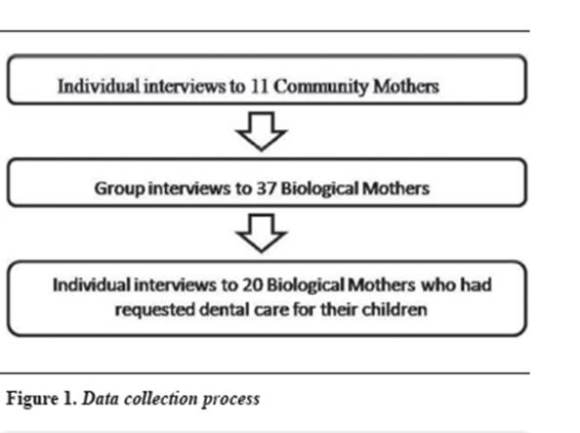

The Ethics Committee of Universidad de Antioquia School of Dentistry approved this study's protocol. This was a descriptive study based on responses to individual and group interviews that the researchers performed with biological and community mothers. This study included the participation of 37 biological mothers (BM), 20 of whom had previous experience seeking dental consultation for their children. Also, 11 community mothers (CM) were included because the time they spend with children apparently gives them the possibility of participating in decisions dealing with children's potential access and even in some cases real access to consultation.

These biological and community mothers were part of one of the Associations of Community Homes of Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, ICBF, located in Florencia, a neighborhood in the city of Medellín. According to the city's public services provider, this district is mainly inhabited by families from levels 2 and 3 of the socio-economic strata. Most children came from nuclear families whose parents (one or both) work as employees under fixed-term contracts and were therefore temporarily enrolled in the contributory scheme of the Social Security General System. Other children came from families affiliated to the subsidized scheme.

Community mothers were contacted first in order to explain them the study's procedures. They later helped bringing biological mothers together. Data was collected in a progressive manner figure 1 as follows: first, 11 CMs were individually interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire at the community homes they were in charge of. As already discussed, they were included in the study due to their important role in childcare, since children often spend more time with them than with their own BM, who in many cases work long hours away from home. During the time they share with children, community mothers identify their health needs, actively participating in oral and body care, and sometimes in decisions dealing with seeking care for children who they think need it.

The second stage included group interviews to the 37 BMs at community homes. Four interviews were conducted with the participation of 8 to 10 women each. During the third stage, the 20 BMs that reported taking their children to dental consultation in the past were individually interviewed again, in order to thoroughly explore their experience of interaction with health care services.

Both interview types (individual and collective) included questionnaires previously subjected to a pilot test, and in no way meant to be too strict in terms of number and type of questions, since they depended mainly on the answers the women were giving. In fact, spontaneous narration of experiences was another form of data collection. Each session was attended by two researchers, one as an interviewer and the other as observer and rapporteur. All the sessions were recorded with the mothers' consent and later transcribed.

The interviews addressed the following topics: oral health estimation; beliefs and practices about oral care; knowledge about health rights; perception of the child's oral health status (perception of need); strategies of need resolution (institutional, non-institutional, self-restraint); knowledge about dental care; search for service versus perceived need; attended need (use of service) versus perceived need; previous consultations; cause of consultation; site of health care provision; purpose of consultation (preventive, curative, checkup); comprehensive care (medicines, diagnostic aids); timeliness of care; continuity; perception of service quality; confidence and commitment to treatment; reason for not consulting; reasons for not using services, among others.

Data processing and analysis were performed at the same time of data collection. The researchers had several meetings, which allowed adjusting the questionnaires as knowledge on participating mothers increased. This led to more personal interviews with women who had used dental service for their children—an aspect that was not initially planned.

The texts resulting from the transcriptions were read and organized in a systematic manner, in order to delete repetitions and to identify similar or related responses (fragments of text), which were gradually sorted out. Each group of responses was labeled with a word or a short phrase for the researchers to easily identify the issues arising in the study. That way, they were able to identify trends from the responses and, subsequently, always working as a team, the necessary conceptual connections were done in order to produce the final descriptive arguments, which are presented below as results.

RESULTS

COMMUNITY MOTHERS

Perception of the oral health status of children under their supervision

With respect to CMs' perceptions about children's oral health status, we can say that, due to their close relationship with children, these women may identify irregularities or problems and can even describe the situations. Most of them perceive their children's oral health status as good and easily identify those who have obvious problems. All the testimonies in this article are taken from the individual and collective interviews during the research process.

Their perception about children's oral health status is based on everyday contact with them and from the medical reports BMs should bring with them as a requirement for enrolment in the community home. It should be noted, however, that they often question the credibility of such a document, since they do not trust the way moms get them. On other occasions, they are doubtful because the bill of health is issued by a physician and not by a dentist. "...When they enter, we always request the certificates, and they all seem to be good", says another CM.

CMs play a role in "screening" child health problems in terms of overall health (e.g. malnutrition) and oral status. In the case of oral health problems, they say they notice these issues when children reject food or complain while eating. This means that CMs are often aware of children's oral health problems earlier than BMs are, or they are the ones who actually notice them. "One sometimes realizes because the child does not eat, or things like that".

Demands for children health service

CMs consider that it is the parents' responsibility to seek medical and dental services for their children and that their role is only to inform parents about the problems they detect. However, they say that parents sometimes neglect to take their children to checkups, so they end up involved in care seeking, although in most cases they do so in order to comply with the requirements of ICBF (children's official welfare institution, by its Spanish initials). "Since we have to fill in the forms, including medical and dental examinations as part of the paperwork, sometimes we ourselves bring them to the doctor's office for the examinations", says another interviewed CM.

They also say that, although they consider this task to be the parents' responsibility, they must make sure the consultations are done and certifications issued. This sometimes creates conflicts with parents or caregivers, who focus too much on obtaining a certificate and move away from the real purpose: ensuring the child's oral health.

CMs also point out that it is still common to hear parents say that "the child is too little to be taken to dental consultation". Some of them share this idea with parents and, moreover, say that the professionals themselves are the ones who often help spread this idea among mothers, since many show no interest in caring for little kids because they think there will be problems during consultation. "...when they are very young kids, under two years of age, many doctors say that teeth are just adjusting so there is no need to consult until they turn three".

They have the perception that access for children covered by the SISBEN (System of Beneficiaries Selection) is difficult, while those under the contributory scheme have more access. "...some have their EPS (service provider by its Spanish initials, or HMO: Health Maintenance Organization) and I see that these moms easily get appointments and have good service, but those covered by SISBEN do not receive a dental bill of health and should consult a private office.

In addition, CMs recognize that a significant number of children come from families with economic hardship; many come from households headed by the mother, so it is difficult for them to seek care, even when covered by social security benefits. However, even if they perceive that families have economic difficulties that prevent them from seeking health care for children, they also admit that in some cases parents lack interest. "Appointments are sometimes hard to get, but also many mothers do not seek appointments and are careless".

BIOLOGICAL MOTHERS

Knowledge of children's oral health status and care needs

There was a tendency among the mothers to say that they indubitably know their children's oral status. According to these women, they can say so because they observe the kids brushing at home and are informed by dentists during consultation. In addition, it became clear during group discussions that the mothers positively value—at least discursively—dentition and oral health at this stage of life.

Concerning treatment needs, the more general tendency is for mothers not to feel such needs. This is consistent with the perception about their children's good oral conditions. However, we could also observe that felt treatment needs are influenced by considerations such as the child's age and the mothers' personal experience with previous dental care services, which are often very traumatic. "Oh, no, when I was little, it was bad going to the dentist; I don't want my girl to go through the same".

Demands for dental care and barriers to accessing services

The factors influencing the decision to seek dental care for children vary widely among mothers. Some say that such decision was mediated by the guidelines set by the Growth and Development Program, which motivated them to consult; others have done so by their own initiative, "thinking about the child's wellbeing", and yet others by complying with institutional requirements: "I took him to the dentist because I was requested a bill of health; I believe most do that for the same reason".

Those who have not sought dental services argue that they are "sure" their children have no cavities or other problems requiring consultation. Some others do not feel the need to consult, influenced by the opinions they receive from other people, including health care professionals, concerning the child's age. Finally, some say that when they decide to consult they are rejected by the institutions, on the grounds that "the child is very little". "…this happened to me last year (...) he was not going to be examined because he was under age... they said that you can request dental appointments only after the child turns four".

There was a clear tendency of mothers affiliated to the contributory scheme to classify booking an appointment as "easy". "… I just call and they give me the appointment. If it is for the girl, the appointment is usually scheduled within the next three days...", (mother G3) says. On the other hand, mothers under the subsidized scheme usually receive negative answers or delayed service. "It is not easy for me; I've been trying to get an appointment for about a month, but nothing has happened".

MOTHERS WHOSE CHILDREN HAD A HISTORY OF DENTAL CONSULTATION

Perception about the conditions of dental care access

Since most interviewed women belong to the contributory scheme, they mention few barriers to access. However, opinions on timeliness of appointments are varied. Some explicitly stated that they usually get appointments immediately and for a period of no more than a week, "I just dial the number and say: I have an order for a dental appointment and I get it; that one is faster, as for a week", said Berenice; other women, however, report that appointments are often delayed but never denied. The few women covered by the subsidized scheme do mention rejections.

In addition, some mothers point out that Service Provision Institutions (or IPS for their Spanish initials) offer improved access opportunities, such as the possibility of picking evening appointments for those who have full time jobs. "Yes, they ask you what your best time is".

Perceptions about geographical barriers do not show single tendencies either. Several women expressed that health centers are accessible, while others complain about the distances and costs of getting there. "I have to request permission, go home, take two buses, then go back home again to bring the girl back and then return to work; it is so inconvenient, that reason only is enough for not booking an appointment".

In general, mothers referred to children's age as the problem that most interferes with access to dental appointments, since EPSs greatly limit care services to children younger than three years. The reason for this limitation is the "development" stage children are going through vs. their actual "needs". "I requested one appointment when she was about two or two years and a half, and I was told that children start to be seen by dentists by the age of three, so I had to wait until she turned three".

Satisfaction with received health care

We found out an overall positive tendency to be satisfied with the services provided to children, especially in terms of the professional's attitude towards the child and resolution of the issue consulted. "…they were very careful and treated her like a little girl. They were very gentle and offered a good service. She had a radiograph taken...".

However, some mothers did complain of certain characteristics of the service, such as treatment by the professionals or auxiliary staff and limited communication with the professional. The most frequent complaint was about the short time available for professional care. "The way the dentist treated my girl was average, like they usually treat adults, nothing special, in a hurry as always, and pressed by time; he was about the same when saying good-bye".

DISCUSSION

Bearing in mind that access to services—dental care in this case—is part of equity in health, this study sought to identify the obstacles kids face during early childhood to access these services. The interest on this age group arises from the importance of timely and effective dental care during the early years of life, not only for the amount and type of oral problems that can be prevented, but also for the impact of these services on the healthy growth and overall development of children of both sexes.8, 9

It is important to have into account, however, that by health care access we do not only refer to the possibility of getting appointments (the entrance to the service), but to an overall category that includes, considering the dimensions of potential and real access, the entire process since the time the user, in this case mothers, perceive the need, seek treatment, access services, and get the child's needs solved. In other words, this category refers to who demands the service and who provides it.10, 11 In the case of dental care, offering an effective solution to the needs usually requires not just one but several appointments, during which the user-service interaction occurs.

- Family resources, first economic obstacle for children's access to dental services

- The child's age, the second largest cultural and organizational obstacle

- Organizational and geographical obstacles

These mothers' narratives corroborated that families' socio-economic characteristics represent a typical profile of poor and vulnerable families—which is not exactly a finding of this study because those characteristics were part of the selection criteria for participating families—. These criteria, such as low socioeconomic level (2 and 3), low mother's education level, type of family (in many cases, mother-headed monoparental nuclear families), and the mother's absence from home due to job-related reasons, with limited purchasing capacity to travel or to reach care centers, force parents to focus on seeking sustenance for their children, and therefore they have little time to address other needs that are not seen as priority. These characteristics are potential barriers to care access, not only from an economic perspective (purchase capacity, cost of access to the health center), but also from a cultural point of view (values, attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs of the population towards the use of services).12-15

The child's low age stands out as one of the most important obstacles for infants to receive attention, whether preventive or curative. On the one hand, we find mothers who often want to "protect" their children, saving them from the anxiety or fear generated in the dental office, or from the pain caused by therapeutic procedures, especially when they have oral conditions already identified. On the other hand, institutions and health professionals "disqualify" children by their young age to receive dental care, in order to avoid confrontations with the behaviors of kids and because it takes more consultation time, not meeting the institutional policies on professional productivity.

This is one of the biggest obstacles and must be beaten with sufficient information, education, and communication on the importance of timely care, and with the resources available to dentistry to provide friendly and welcoming care services in order to decrease the child's tensions as much as possible. While one of our positive findings is that every day more mothers (both community and biological) have a positive appraisal of the importance of children's oral health, this obstacle impedes demanding care, i.e., mothers are interested and concerned for children's oral health, but in many cases they do not seek services. This finding has been common in other studies related to this population or the school-age population.16-18 Also, the institution that houses children should contribute to overcome this barrier by re-considering the oral bill of health as a requirement, not as an administrative formality, but as an opportunity for children to receive the service they actually need.

In terms of health personnel and institutional policies, which usually discourage mother's demands, this obstacle implies legal, ethical, and political considerations. First, because current legislation clearly states the obligation of caring for children;3 second, because professional ethics calls for non-discrimination of users by any condition and much less by their age in the case of children; and third, because service-related policies should focus on more timely and early care to achieve true prevention and thereby guarantee the right to health of services users.19-21

It was evident that barriers such as the opportunity to book an appointment, the continuity and quality of services, as well as schedules and the location of health centers, are less outstanding but real obstacles, according to the mothers' narratives. This type of barriers, that usually depend on administrative decisions, are often found in specific studies on dental care.22-24

These obstacles have repeatedly been noted because they indicate non-compliance with official regulations, and to overcome them it would be enough for control agencies to act consistently. On the other hand, from the organizational perspective, it would be an excellent opportunity for the institution that houses children to train community mothers in identifying early signs of oral problems in children, actively participating as observers, which, according to primary care, may be the first step at the community level.25

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we may say that children under the age of six accessing dental consultations of preventive or curative nature is still far from being ideal—agreeing with other studies on the same topic—. Many children of the lower strata mainly face multiple barriers to access this service, and even health insurance itself does not guarantee access, as shown in this study. No doubt the most frequent barriers are of economic type, and originate in families' scarce resources or in the way services are organized, but there are also cultural and organizational obstacles, as evidenced by the mothers' responses.

These findings are not significantly different from those of other studies on accessibility among other social populations and age groups. Indeed, access to health in Colombia has a clear tendency to inequality, because the barriers identified in this study are aggravated by the logic of market (access is granted to anyone with purchasing capacity) within the organization of services, so that the idea of health as a fundamental progressive right is constantly fading.26, 27

REFERENCES

1. Aday, LA; Andersen R. Exploring dimension of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1983; 18(1): 49-74. [ Links ]

2. Colombia. Ministerio de la Protección Social. Política Nacional de Prestación de Servicios de Salud. Bogotá: El Ministerio; 2005. [ Links ]

3. Colombia. Ley 1098 de 2006, por la cual se expide el Código de la infancia y la adolescencia. Bogotá: El Congreso; 2006. [ Links ]

4. Noro LR, Roncalli AG, Mendes FI, Lima KC. Use of dental care by children and associated factors in Sobral, Ceara State, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública 2008; 24(7): 1509-1516. [ Links ]

5. Medina-Solis CE, Maupome G, del Socorro HM, Perez-Nunez R, Ávila-Burgos L, Lamadrid-Figueroa H. Dental health services utilization and associated factors in children 6 to 12 years old in a low-income country. J Public Health Dent 2008; 68(1): 39-45. [ Links ]

6. Locker D. Deprivation and oral health: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000; 28(3): 161-169. [ Links ]

7. Ramírez BS, Escobar G, Franco AM, Martínez MC, Gómez L. Caries de la infancia temprana en niños de uno a cinco años. Medellín, Colombia, 2008. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2011; 22(2): 164-172. [ Links ]

8. Gillcrist JA, Brumley DE, Blackford JU. Community socioeconomic status and children's dental health. J Am Dent Assoc 2001; 132(2): 216-222. [ Links ]

9. Feitosa S, Colares V, Pinkham J. The psychosocial effects of severe caries in 4-year-old children in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública 2005; 21(5): 1550-1556. [ Links ]

10. Aday L, Begley C, Lairson, Slater C. Evaluating the medical care system: effectiveness, eficiency, and equity. Ann Arbor: Health Administration Press; 1993. [ Links ]

11. Frenk J. El concepto y medición de la accesibilidad. Salud Púb Méx 1985; 27(5): 438-453. [ Links ]

12. Bonanato K, Pordeus IA, Moura-Leite FR, Ramos-Jorge ML, Vale MP, Paiva SM. Oral disease and social class in a random sample of five-year-old preschool children in a Brazilian city. Oral Health Prev Dent 2010; 8(2): 125-132. [ Links ]

13. Eckersley AJ, Blinkhorn FA. Dental attendance and dental health behaviour in children from deprived and non-deprived areas of Salford, north-west England. Int J Paediatr Dent 2001; 11(2):103-109. [ Links ]

14. Sohn W, Ismail A, Amaya A, Lepkowski J. Determinants of dental care visits among low-income African-American children. J Am Dent Assoc 2007; 138(3): 309-318. [ Links ]

15. Aida J, Ando Y, Oosaka M, Niimi K, Morita M. Contributions of social context to inequality in dental caries: a multilevel analysis of Japanese 3-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008; 36(2): 49-156. [ Links ]

16. Medina-Solís C, Maupomé G, Ávila-Burgos L, Hijar-Medina M, Segovia A, Pérez-Núñez R. Factors influencing the use of dental health services by preschool children in Mexico. Pediatr Dent 2006; 28: 285-292. [ Links ]

17. Siegal MD, Marx ML, Cole SL. Parent or caregiver, staff, and dentist perspectives, on access to dental care issues for head start children in Ohio. Am J Public Health 2005; 95: 1532-1538. [ Links ]

18. Mouradian WE, Huebner CE, Ramos-Gómez F, Slavkin HC. Beyond access: the role of family and community in children's oral health. J Dent Educ 2007; 71(5): 619-631. [ Links ]

19. Echeverri E. La salud en Colombia: abriendo el siglo… y la brecha de las inequidades. Rev Gerenc Políticas Salud 2002; 1(3): 76-94. [ Links ]

20. Vega R. Dilemas éticos contemporáneos en salud: el caso colombiano desde la perspectiva de la justicia social. Rev Gerenc Políticas Salud 2002; 1(2): 49-65. [ Links ]

21. Observatorio Seguridad Social. Grupo de Economía de la Salud. Equidad en salud: panorama de Colombia y situación en Antioquia. Medellín: Observatorio Seguridad Social; 2005. [ Links ]

22. Kramer PF, Ardenghi TM, Ferreira S, Fischer L de A, Cardoso L, Feldens CA. Use of dental services by preschool children in Canela, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública 2008; 24(1): 150-156. [ Links ]

23. Franco AM, Santamaría A, Kurzer E, Castro L, Giraldo M. El menor de seis años: situación de caries y conocimientos y prácticas de cuidado bucal de sus madres. Rev CES Odont 2004; 17(1): 19-29. [ Links ]

24. Franco-Cortés AM, Ramírez-Puerta BS, Escobar-Paucar G, Isaac-Millán M, Londoño-Marín PA. Barreras de acceso a los servicios odontológicos de niños y niñas menores de 6 años pertenecientes a familias desplazadas. Medellín. Rev CES Odont 2010; 23(2): 41-48. [ Links ]

25. Vega-Romero R, Acosta-Ramírez N, Mosquera-Méndez P, Restrepo-Vélez O. Atención primaria integral de salud. Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor; 2009. [ Links ]

26. Mejía A, Sánchez A, Tamayo J. Equidad en el acceso a servicios de salud en Antioquia, Colombia. Rev Salud Pública 2007; 9(1): 26-38. [ Links ]

27. Rubio-Mendoza, ML. Equidad en el acceso a los servicios de salud y equidad en la financiación de la atención en Bogotá. Rev Salud Pública 2008; 10 Supl 1: 29-43. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en