Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versión impresa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.25 no.2 Medellín ene./jun. 2014

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

BELIEFS, KNOWLEDGE, AND ORAL HEALTH PRACTICES OF THE MAPUCHE-WILLICHE POPULATION OF ISLA HUAPI, CHILE

Clara Misrachi Launert 1; José Manríquez Urbina2; Valentina Fajreldin Chuaqui3; Kiyoshi Kuwahara Aballay4; Carolina Verdaguer Muñoz4

1 Dental Surgeon, Master in Education, Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile

2 Surgeon, Magister in Public Health, Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile. Email: jmanriquezu@gmail.com

3 Social Anthropologist, Magister in Public Health, Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile

4 Dental Surgeon, School of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile

SUBMITTED: MAY 28/2011-APPROVED: OCTOBER 8/2013

Misrachi C, Manríquez J, Fajreldin V, Kuwahara K, Verdaguer C. Beliefs, knowledge, and oral health practices of the Mapuche-Williche population of Isla Huapi, Chile. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2014; 25 (2):

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: In Chile, the law recognizes the existence of eight indigenous peoples, representing 4.6% of the total population; 87.3% of them are Mapuche. This population presents worse economic, educational and health indicators than the general population. Isla Huapi is a rural locality in the South of the country. It is geographically and culturally isolated; it lacks health care access and suffers poverty and social marginalization. The objective of this study was to describe the determinants of oral health behavior in the Mapuche-williche population from Isla Huapi and their distribution by sex and age. METHODS: this was a descriptive cross-sectional study using instruments of beliefs, knowledge and oral health practices previously validated in the population of Isla Huapi, consisting of 417 subjects, 98% of whom are Mapuche. The analysis was performed with STATA® 11. RESULTS: 77 subjects (53% females) were interviewed. 66% of them mentioned that "bad washing" is related to dental caries, 62% "uses natural remedies" for oral health care, and 80% admitted brushing their teeth at least twice a day. There was significant difference in terms of "motivation" to consult the dentist (higher motivation levels in women) and "perceived barriers to health care access" (older adults perceive more difficulties). CONCLUSSION: there is plenty of information on the impact of social and behavioral determinants (SBD) in the implementation of health promotion strategies. However, in Chile there are few specific oral health programs for indigenous peoples. This is a pioneering study in establishing a cross-cultural work in oral health.

Key words: oral health, indigenous peoples, knowledge, practice, health behavior.

INTRODUCTION

The Indian Act1 recognizes eight indigenous peoples in Chile, representing 4.6% of the country's total population, out of which 87.3% is Mapuche.2 This population presents economic, educational and health indicators different to those of the non-indigenous population, in a context of social and political vulnerability.3

In 2005, the Ministry of Health of Chile launched a program of socio-cultural epidemiology with the objective of estimating equality gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous populations, in order to implement more effective health interventions. As part of the first methodological strategies, ethnicity was integrated in morbidity and mortality records, allowing the identification of most common health problems among the indigenous populations in Chile. Actually, this contribution not only allowed to characterize the most common health problems with an ethnic distinction, but also revealed systematic gaps in indicators related to social injustice, such as child mortality rates and mortality from tuberculosis, which are significantly more concentrated in the regions where these populations live in comparison to non-indigenous populations.4 Despite the aforementioned efforts, the studies on indigenous peoples have generally focused on identifying general health problems, especially in urban areas.

According to the Indigenous Peoples Health Program of the Pan American Health Organization, one of the main reasons for the current inequalities between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples is the nation's poor knowledge on what they are today and what they were in the past.5

The Mapuche population concentrates in rural and urban areas of the South of the country (59%) and in the capital city (30.3%).6 Isla Huapi, a rural locality of the commune of Futrono, is located in Los Ríos Region in Southern Chile. The region's Mapuche population represents 11.3% of the regional total, the national average being 4,58%.2 Located in Ranco Lake, Isla Huapi faces particular geographic and cultural isolation conditions, due to the lack of terrestrial roads, and only a ferry connects twice a day the island's population with the nearest town, which offer services from low to medium complexity.7

Only a few studies about beliefs and practices in relation to the oral health of indigenous peoples have been conducted in the world. In addition, most of these studies have failed to explore the phenomenon, focusing on describing the results of the application of telephone questionnaires. A review of these studies shows that the major disparities are connected to oral health status instead of beliefs or practices.8

In recent decades, there have been few studies on this subject within indigenous populations. A study by Tayanin et al in the Vietnamese Kammu people highlights the importance of aesthetic elements in implementing caries prevention strategies.9 On the other hand, Jamieson et al, in a qualitative study in Australian indigenous population, aimed at generating input for oral health promotion and prevention interventions with cultural relevance, state that the historical legacy, as well as knowledge on how to access the health system, are so significant to these communities that they are considered to be the main determinants of oral health status.10

In 2008, Pirona et al conducted a study on the socio-cultural meanings of oral health and disease among Añu indigenous from Zulia State, Venezuela. They found out that for this community oral health is strongly associated with spiritual and environmental elements, taking into account that in their worldview the mouth represents a meeting point of both spheres. In addition, they concluded that for this population it is possible to have a mixed health system integrating both the official dental medical system and that of their own.11

In Chile, there are few specific oral health programs aimed at indigenous peoples, or even studies that allow diagnosing the oral health status of these peoples. The present study focuses on the Mapuche population living in Isla Huapi and is intended to visualize the local realities with a view to call the attention of the country's public health decision-makers about the need for an intercultural work in oral health.

Bearing all this in mind, the objective of this study was to describe the beliefs, knowledge, and oral health practices of the indigenous Mapuche-Williche population from Isla Huapi and its distribution according to sex and age, in order to activate the need for oral health promotion programs aimed at this population.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study. The study population included all the inhabitants of Isla Huapi in Los Ríos Region by the year 2009 (N = 417 inhabitants). A convenience sample design was used in this study. The researchers interviewed 77 people meeting the inclusion criteria: people of both sexes, older than 10 years, residing in Isla Huapi, and with at least one surname of Mapuche origin. Their socio-economic level was obtained from information from the official health insurance system (Fonasa).12 Data were collected through guided questionnaires, including instruments previously validated for standard population, such as the "Nakazono's questionnaire of oral health beliefs".13, 14 Also, through guidance and systematic meetings with experts in the field, the researchers validated the contents of instruments such as "knowledge on oral health", "beliefs about the etiology of dental pathologies", "practices associated to dental pathologies" and "preventive measures in dental pathologies". The internal consistency of these instruments was validated through the standardized Cronbach's Alpha, considering a value over 0.7 as the adequate one.

Concerning the applied questionnaires, they were administered by a previously calibrated examiner. The first questionnaire was "Nakazono's oral health beliefs", developed within the theoretical framework of "health belief model"13 with these dimensions: "perceived severity", "benefit of preventive practices", "benefit of plaque control", "dentist effectiveness" and "perceived importance of oral health". It consists of 18 questions whose answers range from "totally disagree" (1 point) to "totally agree" (4 points). The highest total scores indicate the most favorable beliefs toward oral health.

The "oral health beliefs" questionnaire, on the other hand, consists of 21 statements about health care and indicators of proper oral health status, to which respondents react by saying whether they are true, false, or do not know. Correct answers add 1 point, and the incorrect ones and those marked as "I don't know", add 0 points. Like the previous questionnaire, the highest scores represent institutionalized knowledge on formal dental practice.

The variables were described as summary measures (mean, median, and mode) along with measures of dispersion (standard deviation). Before the statistical analysis, the distribution of continuous quantitative variables was determined (normality). Analysis of the variables with normal distribution was performed by the t test (Student's t test) and the ANOVA test of analysis of variance; otherwise, the Mann Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis test for three or more groups was applied. The analyses were performed with the STATA® 11 computer program.

Prior to questionnaire application, the informed consent process was performed in order to fully describe and explain the steps of the study, as well as the commitments of the research team and the participants. Each subject's signature was obtained before the questionnaires. This study was consistent with the ethical guidelines and general regulations for research with humans, provided by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Universidad de Chile School of Dentistry.

RESULTS

The population of Isla Huapi consists of 417 people and is 98% Mapuche. The indigenous character of this community was obtained by a formula validated by indigenous studies specialists. Self-identification and having at least one Mapuche surname are the main features for this characterization.3

Of the total study population (n = 77), 46.7% were males (n = 36) and 53.3% females (n = 41). The average age was 32.4 years, with a median of 30 years and a mode of 10 years. 45.4% of participants claimed to be single and 24.6% married.

Concerning health insurance, 100% of the population is attended through FONASA, and 94.8% are classified under category A, the one with the least resources (less than US$300 monthly family income). 88.3% did not have a job with a regular monthly salary, with significant differences by gender (p < 0,05).

Regarding the frequency of dental consultations, 44% said they did not see a dentist in the past 2 years, while 33.7% did so only once. On the other hand, 2.6% sought treatment due to dental-related discomfort. There was no difference by gender (p > 0.05).

In terms of oral health knowledge by sex and age group, 64.6% of the respondents provided right answers in relation to the characteristics of oral health. The median percentage of correct answers was 61.9%. No significant differences by sex or age group were found.

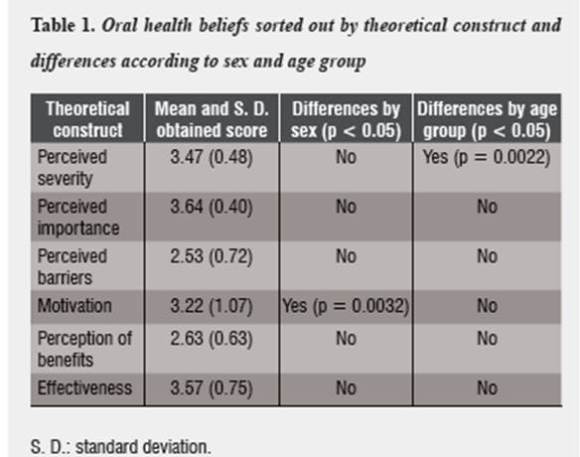

In relation to the dimensions studied with Nakazono's questionnaire of oral health beliefs, most respondents obtained high scores (≥ 3 points) in the following components: perceived severity of dental problems, perceived importance of dental problems, motivation, and effectiveness. The lowest values were obtained in the dimensions of perceived barriers and benefits of intervention. The statistical differences between males and females and by age groups are summarized in table 1.

In relation to "beliefs about the etiology of caries", although there was no significant difference among the causes of caries by sex or age group, not brushing one's teeth appears as the most frequent (66.2%), followed by diet, don't seeing the dentist and using a hard toothbrush. Other causes are also common, reflecting the existence of typical etiological notions of the popular local medical system or of that with indigenous roots, such as the presence of "air on teeth" and "pasmo".

With respect to the cause more often identified as producing dental caries, not brushing one's teeth (66.2%) was the most frequent answer. On the contrary, inheritance was considered the least important (1.3%).

There are significant differences (p < 0,05) by sex and age group when tooth decay is attributed to not seeing the dentist. This is significantly more often cited by women and by the age group of 15 to 30 years as being the most important cause.

In relation to bleeding gums, 77.9% considered using a hard brush as the most important cause, while 1.3% said the opposite. There were no significant differences by sex or age group.

Most of the studied population (71.4%) considered not brushing one's teeth as the most important cause for bad breath, being a greater belief among males. Other causes include "caries", "drug consumption" and other systemic conditions such as "gastric problems".

In relation to tooth loss, not washing the teeth was the most frequent answer (51.9%). On the other hand, none of the respondents considered inheritance as a determinant. Also, pregnancy as a cause presents significant differences by age group (p < 0,05), with a larger number of answers in the group from 31 to 60 years of age, followed by the age group of 0 to 14 years. Other causes include "caries" and "decalcification".

In terms of "practices associated with dental diseases", it is important to note that apart from the high percentage of respondents who use natural or home remedies (62.3%) for treating toothache, with differences by sex or age group, there were no other significant differences.

In relation to practices associated with bleeding, 55.8% believe that no variable determines this symptom, while 1.4% considers it is associated with medicine intake. About bad breath, 74% think that washing with more frequency is enough to solve it, with no significant differences. It should also be noted that 60% of the subjects responded affirmatively to the question ask the dentist if a tooth is lost for any reason.

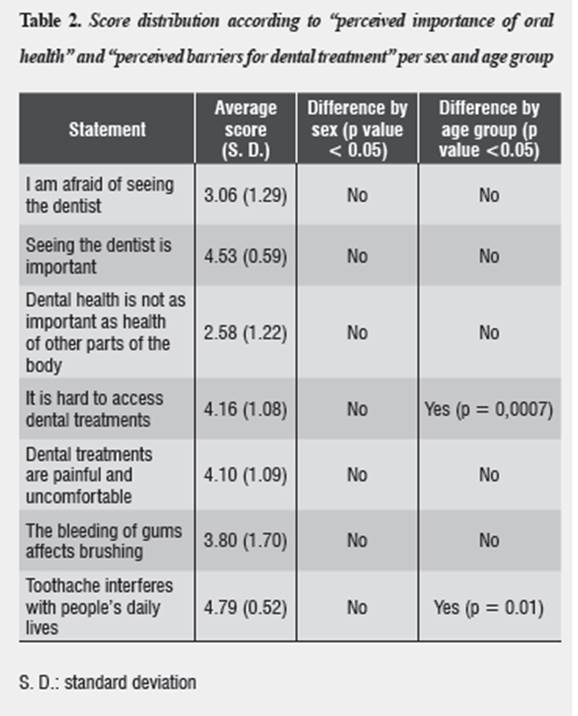

As for response distribution in relation to "perceived importance of oral health" and "perceived barriers for dental treatment", the response toothache interferes with people's daily life was the most frequent (4.79 on average score in a scale ranging from 0 as the minimum value to 7 as the maximum), with significant differences per age group. These scores are summarized table 2.

Regarding the "perceived barriers for dental treatment", toothache is recognized as the most important motivation to seek dental care. There is a very significant difference (p = 0,0007) in relation to age group, and there is also a significant difference (p = 0.001) in the question related to toothache.

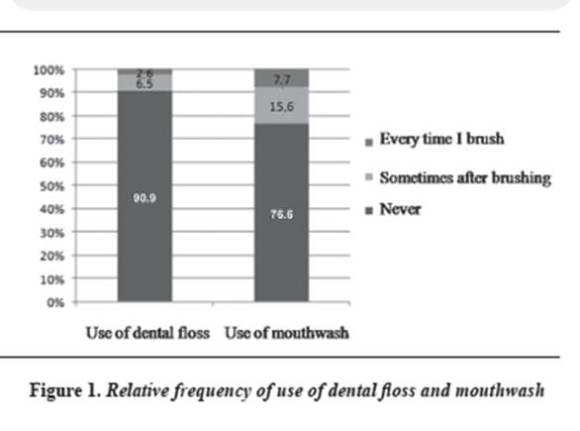

Preventive behaviors were significantly predominant among women. In addition, 80.5% of respondents reported brushing teeth at least 2 times a day, including once before bedtime. There was no relationship between perceived oral health importance and frequency of brushing. There were no significant differences by age group or gender among the groups in relation to the use of dental floss and mouthwash.

Figure 1 summarizes the responses on the use of dental floss and mouthwash.

Almost all the population (98.7%) fails to make preventive controls with the dentist. No significant differences were found by sex or age group.

DISCUSSION

The population of Isla Huapi belongs to the cultural williche community, which presents dialectal differences with respect to the standard language ("mapudungun"). These communities are characterized by living in territories near lake basins and marine areas, which creates a favorable environment for geographic isolation.

According to the results of the present study, behavioral determinants and socio-demographic aspects seem to be relevant for oral health.13, 14 To understand the importance of this study in an area with the described characteristics, it is critical to consider the precarious conditions of access to the health care network as well as indicators of poverty, isolation, and social marginalization and its cultural particularity with respect to the larger society.15

Almost all the study population is covered by the official health insurance system (Fonasa) in its most basic classification (section A), which is associated with precarious employment conditions and informal contracts. In addition, most participants lack a job with regular and systematic payment. Women do not usually have a job with a regular payment, mostly because they work as housewives, while men are jobless or work independently, especially in agricultural work for self-consumption.

A low percentage of this population consults the dentist for issues such as dental pain, tooth decay, and tooth loss. This is mainly due to almost null access to the dentist, since the only permanent offer of free dental care is located in the municipal office of Futrono, situated at an excessive long distance, with transportation along Lake Ranco seldom available and expensive.

In general, the Chilean population seeks dental care in the presence of emergencies,12 mostly for orofacial pain, which agrees with findings in different populations of Chile16 and ethnic groups in the USA.17 In studies conducted by Nakazono et al,13 older adults (Navajos and Lakota) reported fewer visits to the dentist than the general population, even with no evident differences per age group. In the studied Mapuche-williche population, there is a tendency among adults older than 60 years to see the dentist fewer times than the younger population.

It is extremely important to note the difficulty in accessing dental care due to the municipality's geographical conditions, since this situation may be due to the difficulty of accessing dental benefits but also to beliefs and practices concerning one's oral health.

Considering the results obtained from the test used in this study, and comparing our findings with previous national and international studies focusing on native populations, it is important to mention that the results show that oral health beliefs in the study population are not generally favorable to the acquisition of positive oral health behaviors.12, 16, 18-21

However, the adoption of new behaviors is more common among women, who tend to have more positive beliefs. The present study agrees with the findings by Davidson et al17 only in relation to the construct "motivation". Similarly, Nakazono et al13 point out that among their study population the younger age groups have more positive beliefs, disagreeing with the results of our study, in which no significant differences were found by age group.

On the other hand, the study by Misrachi and Saezt18 suggests that the notion about the origin of dental pain is exclusively attributed to the presence of deep or penetrating caries, but in the present study the percentage attributed to these causes is very low, citing lack of oral hygiene and professional care as causes. However, we found out that a low percentage believes that dental pain is caused by "air" or "pasmo", already described by Misrachi and Saez as traditional medical concepts and caused by sudden changes in air currents or temperature.

In contrast to the findings by Misrachi and Saez16 in relation to the causes of tooth decay, in our study respondents do not often mention pregnancy or heredity as determinants. On the contrary, they frequently attribute it to lack of preventive practices such as brushing one`s teeth and seeing the dentist.

In comparing the answers about the causes of gingival bleeding, in our study the respondents mention the use of a hard toothbrush in a great proportion, but in terms of infection or weakness of the gums the answers are drastically lower. On the other hand, attributing gingival bleeding to the absence of oral hygiene practices drastically increases. A high percentage of the subjects do not take any action against gingival bleeding because they do not consider it a problem, similar to that found by Misrachi and Saez.16, 18 On the other hand, the proportion of respondents who use medicines and natural or home remedies for gingival bleeding is low.

Traditional medical systems coexist with biomedical systems, and this is reflected in the use of medicines along with herbs for toothache treatment—a situation also observed in the studies by Misrachi and Saez—.16, 18 Similarly, we corroborated the findings of Pirona and Rincón in the Añu population in Venezuela, where both medical systems also coexist, evidencing the need to incorporate elements of these communities' worldview in oral health prevention and promotion programs in order to achieve more equitable health indicators in relation to non-indigenous populations. This action should be replicated in most Latin American countries due to the high concentration of indigenous peoples in most of them.11

Tooth brushing is more frequent in women than in men, which coincides with the general population.17 It is important to note a bias of information in this regard, since brushing frequency is often determined through retrospective surveys, which probably induced an increased frequency of brushing response in order to conform to the expected social patterns. On the other hand, the frequency of brushing is not an indicator of good oral hygiene, since careful brushing—and not just its frequency—is important for maintaining good oral health.19

Likewise, only a low percentage of the population use dental floss and mouthwash as oral hygiene measures. This is perhaps due to little or no availability within the island, and to the high costs in nearby towns, or even to ignorance of the existence or importance of using these products, due to lack of education and oral health promotion programs.

The frequency of oral hygiene habits is low, as well as care of children's oral health. This is mainly due to lack of knowledge of both the benefits of preventive practices in children and the use of dental floss and mouthwash. It is also due to the difficulty in accessing these articles because of geographical isolation and high costs.

It should be noted that, in contrast to the studies by Jamieson et al10 in indigenous Australian population, where historical legacy and the ancestral knowledge are highly valued by the communities, as well as the aesthetic sense of oral health status (confirmed by Tayaning in the Vietnamese Kammu people),9 the present study did not take into account these elements as determinants, nor were they included in the applied instruments. These elements should be included in community health diagnostics with an intercultural approach and when planning health interventions specifically aimed at indigenous peoples.21

CONCLUSIONS

While the objective of this study was not specifically oriented to traditional medicine in relation to the oral health of the Mapuche-williche population of Isla Huapi, these findings show a coexistence of traditional and biomedical health systems, especially in situations of dental pain.

More sensitive instruments or qualitative methods and approaches could provide even more and better information in this regard, complementing the findings of this study. This could be considered as the main weakness of this research project. Exploratory discourse analysis would better reveal the fundamentals that determine some health behaviors. We suggest performing further studies on indigenous populations in order to learn more about behaviors and beliefs in oral health from the perspective of social actors, highlighting the use of different medical systems.

A portion of the study population believes that certain situations do not constitute dental problems, namely gingival bleeding, tooth loss and tooth decay. On the other hand, approaching the dentist's office to deal with the various dental pathologies is rare, with the exception of treatment for caries, toothache, and tooth loss, but even in these cases the percentages are far from satisfactory. This is mainly due to geographical isolation which impedes access to the dental care, aggravated by the lack of resources to reach the nearest clinic.

It is imperative to improve access to oral health services if we want educational programs on oral health to be successful. Also, emphasis should be made on access to health promotion programs, considering the geographical isolation and the economic precariousness of families. That is to say, the autonomy of the local community in terms of health resources must be strengthened and the training of human resources must be encouraged in order to promote the relationship between the formal health system, the informal traditional indigenous system, and that of the entire community.

In conclusion, an efficient educational program should emphasize knowledge and beliefs in oral health, including the participatory preparation of materials and educational strategies that incorporate intercultural approaches.

Also, in the light of the findings of this study and the methodology used, it is recommended for future studies to explore the existence of socializing agents in oral health, both in the community (including traditional medical specialists of their culture) and as part of the health system, who would act as agents of oral health education. It is also necessary to inquire about the availability of oral health supplies and especially of oral health care within the locality under study, taking into account the net of services in the area and the region. These social determinants of oral health would fully explain the people's beliefs and behaviors in oral health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare not having conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTST

To the community of Isla Huapi at Los Ríos Region, for its collaboration during this research project.

REFERENCES

1. Chile. Ministerio de Planificación. Ley Indígena N.º 19.253 [Revista en línea]. [fecha de acceso 15 de junio de 2009]. URL disponible en http://bibliotecadigital.ciren.cl/gsdlexterna/collect/textoshu/index/assoc/HASH268a.dir/CONADI-HUM0005.pdf [ Links ]

2. Chile. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Estadísticas sociales Pueblos Indígenas en Chile. Censo 2002 [Libro en línea] 2005. [fecha de acceso 20 de marzo de 2009 ]. URL disponible en: http://www.ine.cl/canales/chile_estadistico/estadisticas_sociales_culturales/etnias/pdf/estadisticas_indigenas_2002_11_09_09.pdf [ Links ]

3. Oyarce AM, Pedrero M. Perfil epidemiológico básico de la población mapuche: comunas del área lafkenche del Servicio de Salud Araucanía Sur. Serie Análisis de la situación de salud de los pueblos indígenas de Chile, N.º 4. Santiago: Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2009. [ Links ]

4. Pedrero M, Oyarce AM. Una metodología innovadora para la caracterización de la situación de salud de las poblaciones indígenas de Chile: limitaciones y potencialidades. Notas de Población 2009; 89: 119-145. [ Links ]

5. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Salud de los pueblos indígenas de las Américas [Libro en línea] 2008 [fecha de acceso 21 de agosto de 2013]. URL disponible en: http://www.paho.org/ecu/index.php?option=com_content &view=category &layout=blog &id=684 &Itemid=252 [ Links ]

6. Chile. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas Censo nacional de población y vivienda 2002 [Libro en línea] 2003 [fecha de acceso 21 de marzo de 2009]. URL disponible en: http://espino.ine.cl/cgibin/RpWebEngine.exe/PortalAction? &MODE=MAIN &BASE=CPCHL2KCOM &MAIN=WebServerMain.inl [ Links ]

7. Chile. Municipalidad de Futrono. Casen II, Plan de salud 2009 [Libro en línea] 2010 [fecha de acceso 11 de agosto de 2009]. URL disponible en: http://70.84.139.162/~osvaldo/upload/doc/090417114225_49.pdf [ Links ]

8. Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008; 8: 26. [ Links ]

9. Tayanin GL, Bratthall D. Black teeth: beauty or caries prevention? Practice and beliefs of the Kammu people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006; 34(2): 81-86. [ Links ]

10. Jamieson LM, Parker EJ, Richards L. Using qualitative methodology to inform an Indigenous-owned oral health promotion initiative in Australia. Health Promot Int 2008; 23(1): 52-59. [ Links ]

11. Pirona M, Rincón M, García R, Cabrera R. Significados socioculturales de la salud/enfermedad bucal en los indígenas añu. Ciencia Odontológica 2008; 5(1):27-33. [ Links ]

12. Chile. Superintendencia de Salud. [Revista en línea] 2008 [fecha de acceso 29 de junio de 2009]. URL disponible en: http://www.supersalud.gob.cl/consultas/570/w3-propertyvalue-4008.html [ Links ]

13. Nakazono TT, Davidson PL, Andersen RM. Oral health beliefs in diverse population. Adv Dent Res 1997; 11(2); 235-244. [ Links ]

14. Misrachi C, Sassenfeld A. Instrumentos para medir variables que influyen en las conductas de salud oral. Rev Dent Chile 2007; 99(2): 28-31. [ Links ]

15. Frenz P. Desafíos en salud pública de la reforma: equidad y determinantes sociales de la salud. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Rev Chil Salud Pública [Revista en Línea] 2005 [fecha de acceso 31 de octubre de 2013]; Vol 9 (2): 103 -110 URL disponible en: http://www.derechoinformatico.uchile.cl/index.php/RCSP/article/viewFile/20128/21293 [ Links ]

16. Misrachi L, Sáez M. Valores, creencias y practicas populares en relación a la salud oral. Cuad Méd Soc 1989; 30(2): 27-33. [ Links ]

17. Davidson PL, Rams TE, Andersen RM. Socio-behavioral determinants of oral hygiene practices among USA ethnic and age groups. Adv Dent Res 1997; 11(2): 245-253. [ Links ]

18. Misrachi L, Sáez S. Cultura popular en relación a la salud bucal, en sectores urbanos marginales. Enfoques Aten Primaria 1990; 5(1): 13-14. [ Links ]

19. Borowska ED, Watts TL, Weinman J. The relationship of health beliefs and psychological mood to patient adherence to oral hygiene behavior. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 25(3): 187-193. [ Links ]

20. Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups. Assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008; 8: 26. [ Links ]

21. Fajreldin V. Antropología médica para una epidemiología con enfoque sociocultural. Elementos para la interdisciplina. Cienc Trab 2006; 8(20): 95-102. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en