Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versión impresa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.26 no.1 Medellín jul./dic. 2014

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT NEEDS ACCORDING TO THE DENTAL AESTHETIC INDEX IN 12-YEAR-OLD ADOLESCENTS, CHILE

María Antonieta Pérez1; Álvaro Neira2; Javier Alfaro3; Juan Aguilera4; Patricia Alvear5; Claudia Fierro Monti6

1 Dental surgeon, MA in Pediatric Dentistry, Associate Professor, Department

of Pediatric Dentistry, Universidad de Concepción, Chile

2 Dental surgeon, Centro de Salud Municipal, Cabrero, Chile

3 Dental surgeon, Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas (JUNAEB),

Niebla, Chile

4 Dental surgeon, Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas (JUNAEB),

Ayacara, Chile

5 Dental surgeon, Centro de Salud Municipal, Coronel, Chile

6 Dental surgeon, Specialist in Pediatric Dentistry. Associate Professor,

Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Universidad de Concepción, Chile

SUBMITTED: JUNE 11/2013-ACCEPTED: DECEMBER 3/2014

Pérez MA, Neira Á, Alfaro J, Aguilera J Alvear P, Fierro C. Orthodontic treatment needs according to the Dental Aesthetic Index in 12-year-old adolescents, Chile. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2014; 26(1): 33-43.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the objective of this study was to evaluate the needs for orthodontic treatment in 12-year-old adolescents from the towns

of Ayacara, Cabrero, Coronel, and Niebla, Chile, according to the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI).

METHODS: this was a descriptive, observational,

cross-sectional, and non-probabilistic study. The DAI was applied on 129 12-year-old students from the rural towns of Ayacara, Cabrero, Coronel

and Niebla in Chile. The sample was obtained by availability. Information was gathered through standardized clinical examinations carried out by

previously calibrated researchers, following the WHO recommendations for this type of studies. The DAI criteria were descriptively analyzed, and

statistical significance between males and females was considered.

RESULTS: Out of the 129 patients, 65 (50.4%) were males and 64 (49.6%) females.

35.7% of the examined kids obtained DAI scores = 25, which indicates normal occlusion to minimum malocclusion and means that treatment is

unnecessary or slightly needed, 27.1% obtained scores between 26 and 30, which indicates evident malocclusion and optional treatment, 20.9%

obtained a score = 36, indicating very severe or handicapping malocclusion and mandatory treatment. Significant differences between males

and females (P < 0,05) were observed in terms of missing anterior teeth only.

CONCLUSIONS: there is a high need for orthodontic treatment in the

adolescent population aged 12 years, as 64.3% of the sample presented definite malocclusion.

Key words: cosmetic dentistry, malocclusion, adolescents.

INTRODUCTION

The increasing importance of appearance and dental aesthetics has also increased the demands for orthodontic treatment at early ages.1-4 The decision to seek orthodontic treatment is influenced by the desire to look good, the self-perception of dental appearance, self-esteem, gender, age, and social context.3 These factors substantiate the existence of an epidemiological tool to determine treatment requirements and the need for dental aesthetics in a socially acceptable scale using measurable parameters.1

The Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI) is a tool that helps identify treatment needs and prioritize them according to objective and subjective aspects; therefore, it allows a better use of the limited resources available.1, 5 Furthermore, the DAI has been adopted by the World Health Organization —WHO— as a transversal index to be used on various ethnic groups without modifications.1 It was developed for this purpose in Iowa, United States, in 1986.6, 7 It consists of measuring ten intraoral traits which are individually multiplied by a regression coefficient. These traits are: missing visible teeth, crowding, spacing, diastemas, largest anterior maxillary irregularity, largest anterior mandibular irregularity, anterior maxillary overjet, anterior mandible overjet, vertical anterior openbite, and anteroposterior molar relationship. The product of each measurement is calculated with itself and with a constant, producing a final DAI score. A DAI score of 36 has been established as a reference to differentiate non-disabling from disabling malocclusion.7, 8

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the need for orthodontic treatment according to the DAI in 12-year-old adolescents from different areas of Chile.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study on 12-year-old adolescents of both genders from the municipalities of Ayacara in Los Lagos region, Chilean Patagonia; Niebla, a southern coastal area in Los Ríos region; Cabrero, a rural area in the Bío Bío region, and Coronel, a coastal area of the Bío Bío region. A non-random sample of 210 patients aged 12 years was selected by accessibility (in order to cover a representative sample); they all attended dental checkup.

Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from each patient's parent or guardian, as well as verbal consent from each child before making the models. Patients with no signed informed consent from parents or guardians were excluded from the study, so the final sample consisted of 129 patients: 19 from Ayacara, 26 from Niebla, 40 from Cabrero, and 44 from Coronel.

Four examiners were calibrated on plaster models from patients who were not participating in the study; inter- and intra-observer calibrations yielded Kappa values of 0.7 and 0.8 respectively. The clinical examinations were made by systematic observation on a dental chair. Information was obtained following the WHO recommendations.6

The instruments used included a Hu-Friedy North Carolina periodontal probe and a millimeter ruler. Data were recorded on a form exclusively designed for this study.

The ten DAI components were analyzed on each patient. Each component was multiplied by its corresponding regression coefficient. The result was calculated with itself and with the constant in order to obtain final DAI scores like this: (missing visible teeth x 6) + (crowding) + (spacing) + (diastema x 3) + (largest anterior maxillary irregularity) + (largest anterior mandibular irregularity) + (anterior maxillary overjet x 2) + (anterior mandible overjet x 4) + (vertical anterior openbite x 4) + (antero-posterior molar relationship x 3) + 13 (constant) (table 1).

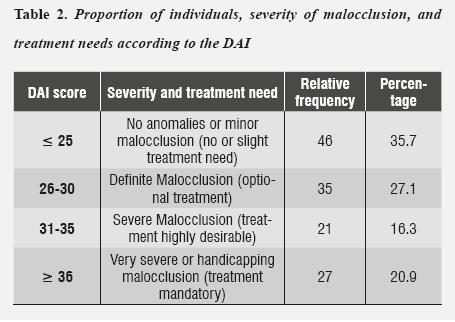

Finally, the results were sorted out according to severity of malocclusion and treatment needs (table 2).

The statistical analysis was performed by X2 test with 5% significance level. Version 15 or SPSS program was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

Out of the 129 examined patients, 65 (50.4%) were males and 64 (49.6%) females. The analysis of frequencies yielded a minimum DAI score of 18 and a maximum score of 66.

35.7% of the examined adolescents obtained DAI scores of = 25, indicating normal occlusion or minor malocclusion and unnecessary to slight treatment need, 27.1% obtained a score between 26 and 30, indicating evident malocclusion and optional treatment, 16.3% obtained a score between 31 and 35, indicating severe malocclusion and highly desirable treatment need, and 20.9% obtained a score of = 36, which indicates very severe or handicapping malocclusion and compulsory treatment.

Analysis of each DAI component between males and females produced the results shown in table 1.

Significant differences between males and females (P < 0.05) were observed in terms of missing anterior teeth only. The other components did not show significant differences (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI) establishes a list of occlusal traits or conditions in categories that are arranged in degrees that allow observing the severity of malocclusions, so that this condition becomes reproducible and informs us about the population's orthodontic treatment needs. This index was applied in Nigerian high schools, showing that 77,4% of students presented normal occlusion or minor malocclusion and 13% had definite malocclusion —which is close to the data obtained in our study—. Similar studies conducted in Malaysia yielded results that are proportionally comparable with our own (minor malocclusion in 62.6% and very severe malocclusion in 7% of the population).9 In a study conducted on 150 Australian children, Chi et al10 reported values that are highly equivalent to the results shown in table 1; in this case, 27% of participants presented severe to very severe malocclusions.

Prevalence worldwide rates in recent years show variations among different geographical areas, ranging from 230:1000 to 770:1000.11, 12 In most cases, this index demonstrates coincidences between normative and subjective criteria, especially in patients with the most severe conditions—which is important in planning therapeutic actions.13, 14

Our study agrees with that of Esa et al,9 who obtained similar results by connecting DAI components and the psychosocial impact on children with respect to their malocclusion.

Establishing the index' cross-cultural validation and duplicability is necessary because cultural standards regarding the position of teeth may differ from country to country, and the degree of attractiveness and treatment need also vary.3, 10 So the standards suggested by the index will be valid if they meet this criterion (this is one of the reasons why it is necessary to apply the index in different sociogeographic locations). Differences in treatment need decisions have been documented among 97 professionals from 9 different countries.15 One of the DAI's characteristics is that it associates both the occlusal and the aesthetic components of anomalies. However, it does not include analysis of patients with severe overbite affecting soft tissues6 or patients with midline deviation. Also, it has the advantage of being an index whose validity and reliability has been proven in numerous studies1, 4, 5, 8, 16, 17

Besides the DAI, there are other indices that pursue the same goal but may provide different outcomes. Previous studies show that these differences arise when analyzing patients' treatment needs with either one or another index, such as the Orthodontic Treatment Need Index.18 Several studies have been conducted using DAI to achieve certain goals, obtaining both dissimilar and concordant results. Poonacha et al8 found out that most patients presented anomalies requiring urgent orthodontic intervention, but Shivakumar et al3 claim that most patients did not require immediate orthodontic intervention. Both studies were conducted in India. Our results agree with the first study but differ in some aspects such as number of patients and ethnic characteristics.

The results show that a high percentage of patients have at least one manifest malocclusion (64.3%); it is also important to note that out of this percentage 20.9% present some kind of disabling malocclusion. By comparing our results with other studies in nearby countries, we find out that there are similar results in Brazil,17 Cuba,18 and Peru,1 although their values are always lower than the ones we found. And when comparing with countries outside the Americas, such as India,3 Turkey,4 and Iraq,5 we find out that the results are significantly lower, ranging between 19.3 and 32%.

The communities of the patients selected for the present study are similar to the communities of other studies in several aspects.17-20 The orthodontic treatments available to patients in isolated and rural sectors are limited by the area's geography (Ayacara) and by the small number of available specialized personnel to provide services; also, attention of orthodontic anomalies is not among the priorities of dental care within the primary health system, and the costs associated to orthodontic treatment are not affordable to patients from these areas.

Dento-maxillary anomalies in 12-year-old adolescents has a prevalence of 53% in Chile;21 it is therefore necessary to assess these patients' orthodontic treatment needs in order to contribute to public health programs and to promote prioritization of treatments and resource planning.

CONCLUSIONS

The percentage of examined patients who showed immediate/short-term orthodontic treatment need is 64.3%. This expresses the need to create and improve current health policies, in order to improve the population's access to orthodontic treatment and to achieve solution to functional and aesthetic problems, which are in direct relation with a person's psychosocial aspects.

The DAI is a simple tool that can be easily replicated by dentists, but it does not include analysis of anomalies that could go unnoticed, such as anterior deep bite or midline deviation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare having no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Bernabé E, Flores-Mir C. Orthodontic treatment need in Peruvian young adults evaluated through dental aesthetic index. Angle Orthod 2006; 76(3): 417-421. [ Links ]

2. Espeland L, Stenvik A, Mathisen A. A longitudinal study on subjective and objective orthodontic treatment need. Eur J Orthod 1997; 19(1): 85-92. [ Links ]

3. Shivakumar K, Chandu G, Shafiulla M. Severity of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment needs among 12- to 15-year-old school children of Davangere District, Karnataka, India. Eur J Dent 2010; 4(3): 298-307. [ Links ]

4. Hamamci N, Basaran G, Uysal E. Dental Aesthetic Index scores and perception of personal dental appearance among Turkish university students. Eur J Orthod 2009; 31(2): 168-173. [ Links ]

5. Al-Huwaizi A, Rasheed TA. Assessment of orthodontic treatment needs of Iraqi Kurdish teenagers using the Dental Aesthetic Index. East Mediterr Health J 2009; 15(6): 1535- 1541. [ Links ]

6. WHO. Dental Oral Health Surveys. Basic methods. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [ Links ]

7. Cons N, Jenny J, Kohout F. DAI: The Dental Aesthetic Index. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa, College of Dentistry; 1986. [ Links ]

8. Poonacha KS, Deshpande SD, Shigli AL. Dental aesthetic index: applicability in Indian population: a retrospective study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2010; 28(1): 13-17. [ Links ]

9. Esa R, Razak IA, Allister JH. Epidemiology of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need of 12-13-year-old Malaysian schoolchildren. Community Dent Health 2001; 18(1): 31-36. [ Links ]

10. Chi J, Johnson M, Harkness M. Age changes in orthodontic treatment need: a longitudinal study of 10- and 13- year-old children, using the Dental Aesthetic Index. Aust Orthod J 2000; 16(1): 150-156. [ Links ]

11. Chevitarese A, Della Valle D, Moreira TC. Prevalence of malocclusion in 4-6 year old Brazilian children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2002; 27(1): 81-85. [ Links ]

12. Kalsbeek H, Poorterman JH, Kieft JA, Verrips GH. Oral health care in young people insured by a health insurance fund. 2. Prevalence and treatment of malocclusions in the Netherlands between 1987-1999. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 2002;109(8): 293-298. [ Links ]

13. Birkeland K, Boe OE, Wisth PJ. Relationship between occlusion and satisfaction with dental appearance in orthodontically treated and untreated groups. A longitudinal study. Eur J Orthod 2000; 22(5): 509-518. [ Links ]

14. Fox D, Kay EJ, O'Brien K. A new method of measuring how much anterior tooth alignment means to adolescents. Eur J Orthod 2000; 22(3): 299-305. [ Links ]

15. Burden DJ, Pine CM, Burnside G. Modified IOTN: An orthodontic treatment need index for use in oral health surveys. Com Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29(3): 220-225. [ Links ]

16. Bernabé E, de Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Comparison of the discriminative ability of a generic and a conditionspecific OHRQoL measure in adolescents with and without normative need for orthodontic treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 64. [ Links ]

17. Costa RN, de Abreu MH, de Magalhães CS, Moreira AN. Validity of two occlusal indices for determining orthodontic treatment needs of patients treated in a public university in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2011; 27(3): 581-590. [ Links ]

18. Manzanera D, Montiel-Company JM, Almerich-Silla JM, Gandía JL. Diagnostic agreement in the assessment of orthodontic treatment need using the Dental Aesthetic Index and the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need. Eur J Orthod 2010; 32 (2): 193-198. [ Links ]

19. Silva L, Carvalho C, Ramos-Jorge M, Almeida I, Martins S. Prevalência da maloclusão e necessidade de tratamento ortodôntico em escolares de 10 a 14 anos de idade em Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brasil: enfoque psicossocia. Cad Saúde Pública 2005; 21(4):1099-1006. [ Links ]

20. Toledo L, Machado M, Martínez Y, Muñoz M. Maloclusiones por el índice de estética dental (DAI) en la población menor de 19 años. Rev Cubana Estomatol [online journal] 2004 [retreived on October 1st, 2012]; 41(3). URL Available at: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script = sci_arttext&pid = S0034-75072004000300006&lng = en&nrm = iso [ Links ]

21. Soto L, Tapia R. Diagnóstico nacional de salud bucal del adolescente de 12 años y evaluación del grado de cumplimiento de los objetivos sanitarios de salud bucal 2000-2010. [Internet] [retreived on November 16th, 2013] URL Available at: http://www.minsal.gob.cl/portal/url/ item/7f2e0f67ebbc1bc0e04001011e016f58.pdf [ Links ]

texto en

texto en