INTRODUCTION

Dental morphology is one of the most studied components of dental anthropology worldwide, as it seeks to understand the behavior of expression (frequency and variability) of crown and root morphology in human teeth.1)(2)(3)(4)(5This process is carried out through observation, recording, and analysis of the morphological traits of crown and root, which become phenotypic shapes of dental enamel, expressed and regulated by the genome of individuals and populations during odontogenesis. These can be either positive (tubercular and root) or negative (intertubercular and phosomorphe) structures with the potential of being or not present in a specific site (frequency) in different ways (variability) in one or more members of a population group. One of the most widely studied dental crown morphological traits (DCMT) is protostylid, due to the high value of its expression as ethnic discriminator of populations.1)(6)(7)(8

According to the tritubercular theory-which explains the possible evolutionary mechanisms that led to the shape and position of cusps in molars based on four phases or stages of development-, there is an enamel collar called cingulum (upper teeth) or cinguloid (lower teeth) which at the height of the gingival third circumscribes the crown of all teeth in the form of a stylar shelf-which during odontogenesis allowed the development of different DCMTs, such as dental tuberculum and the lobes that form the cingulum in anterior teeth, and the so-called tubercles or paramolar cusps (parastyles in upper molars and parastylids in lower molars) that are present on the vestibular, palatal, or lingual surfaces of posterior teeth, as it is the case of protostyle, parastyle and protostylid.9

Perhaps the first approach to the definition of protostylid was done by Bolk in 1914, describing a "supernumerary tubercle or cusp" on the vestibular surface of second and third lower molars, and less frequently on the first lower molars, caused by a fused taper supernumerary tooth. Similar expressions were generically called by Greece, in 1919, as "vestibular tubercles" and by De Jonge, in 1928, as "mesio-buccal prominences".10 Dahlberg referred to the "Bolk tubercle" as a protostylid (the protoconoid stylid), defining it as an elevation or ridge of enamel in the anterior part of the vestibular surface of deciduous and permanent lower molars, which rises from the cingulum in a gingival-occlusal direction closely associated with the mesial-vestibular groove that separates vestibular cusps.10

The first population-based study carried out in a group of Pima indigenous showed that the protostylid is fairly common in some human populations, and its frequency may vary in different populations.11 Later, in his 1956 studies on pre-hominids, Robinson described the development of the "protoconoid cingulum", stating that the hominid protostylid (including its expression in modern man) could be a dental remnant of ancient Australopithecus, although with variations in expression.12 However, today it is not common in the dental environment, and not even in the anthropological field, to name both the protostylid-of the upper molars-and the parastylid as Bolk tubercles.13

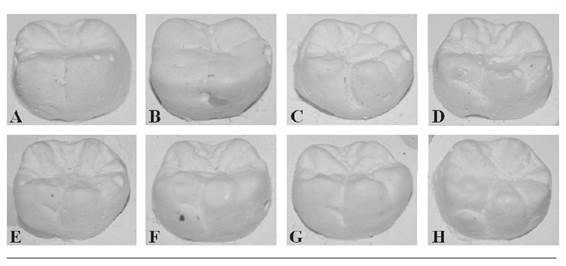

Then, protostylid corresponds to a paramolar cusp that does not make part of the functional occlusal array, and that varies from a groove to a free vertex cusp on the vestibular surface of the mesial-vestibular cusp of deciduous second lower molars, and first and second permanent lower molars. It also tends to express itself as a fovea or vestibular fossa on the groove of vestibular development called P point. The reference plaque was developed by Dahlberg in 1956 at the University of Chicago Zoller Laboratory of Dental Anthropology, and it was later incorporated into the universal system for observation and analysis of dental morphology, known as Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS).14 The ASUDAS plaque proposes eight categories or degrees of expression for lower molars, in which the expressions zero and one are considered to be absent protostylid, while expressions two to seven are considered to be present protostylid (Figure 1).

Figure 1 ASUDAS protostylid plaque. A. Grade 0. Absent; B. Grade 1. Vestibular fossa; C. Grade 2. Vestibular groove curved towards distal; D. Grade 3. Distal groove from the vestibular groove; E. Grade 4. More pronounced groove; F. Grade 5. Deep groove; G. Grade 6. Groove that crosses the vestibular surface and the blunt vertex cusp; H. Grade 7. Free vertex cusp. The dichotomous absence/presence expression is 0-2 / 3-7.

As all paramolar cusps-Carabelli′s, parastylid, mesostyle, interconulus, and interconulid- the protostylid in all of its morphological features (fossa, fissure, groove, crest, and cusps of all sizes) originates in the amelodentinal junction of the vestibular cingulum during tooth morphogenesis of pre-hominids and hominids.15 In primates, this structure has been reducing in the posterior teeth, leaving a series of structures as remnants, mainly on the vestibular and palatal surfaces of upper and lower molars.

Therefore, the protostylid in hominids, as a tubercular or cuspid expression, corresponds to variations of the primitive cingulum,12 while expression of cleft, groove, and fossa results in the residual evidence of variations of protostylid in the hominid primates.

These phenotypic variants were initially described by Miller in 1889, as foramen caecum Milleri, and linked to the expression of the protostylid by Jorgensen in 1954. While it is true that Dahlberg included the vestibular fossa or P point as the first of seven degrees of expression of protostylid, there is still controversy in accepting that this vestibular fossa corresponds to the same foramen caecum described by Miller.16

Given such morphological variability, the goal of this systematic literature review is to determine the behavior of protostylid expression in human populations from Southwestern Colombia, to help clarify the macro-evolutionary processes in the region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic literature review was conducted in the PubMed, Google Scholar, and SciELO electronic bibliographic databases using the PRISMA method.17 The following combination of health descriptors was used: "dental morphology", "dental non-metric traits", and "protostylid", combined with the Boolean operators "+" and "&", which were associated with the "anthropology" health descriptor in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH).

Selection criteria

This review included articles describing the prevalence and variability of protostylid in first permanent lower molars among human populations from Southwest Colombia, in both sexes, using the ASUDAS system, with samples containing at least 30 individuals, since, according to the central limit theorem, a sample is considered significant starting with 30 elements because: "regardless of the functional shape of the population from which the sample is extracted, the distribution of sample averages calculated with samples of size (n) from a population with mean (m) and finite variance (s2) approaches a normal distribution with mean (m) and error standard (s2/n) when (n) increases. If (n) is large (n≥30), sample average distribution can be close to a normal distribution"(.18)

Case reports, topic reviews, and letters to the editor were excluded. The search was not limited by year. The evaluated outcome variable was protostylid frequency in first permanent lower molars. 11 articles were finally selected from the electronic databases including titles and abstracts, and thus obtaining the required data: authors, year, city (state), sample, ethnic pattern, protostylid frequency, and P point frequency.

Statistical analysis

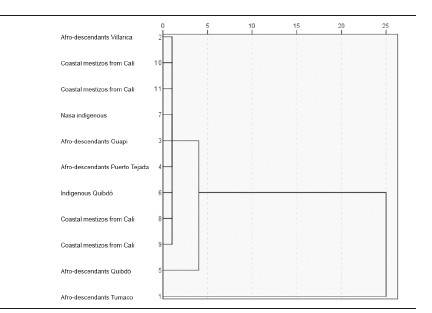

The IBM SPSS® Statistics 21® software was used to observe the behavior of protostylid among the populations taken into account for this systematic review, both among themselves and with respect to other global populations, in order to determine biological distances through the matrix distances based on the hierarchical cluster classification, and the respective dendrogram was obtained through the squared Euclidean distance using the Ward method. Similarly, a dendrogram with different world populations was created.

RESULTS

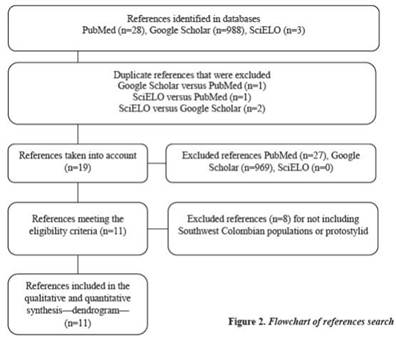

Based on the PRISMA methodology, 1019 articles were found and 996 were excluded (not counting duplicate references) for not addressing the frequency and variability of protostylid. Out of the 19 references taken into account, 8 were excluded for not including Southwest Colombian populations or protostylid as part of their observations (Figure 2).

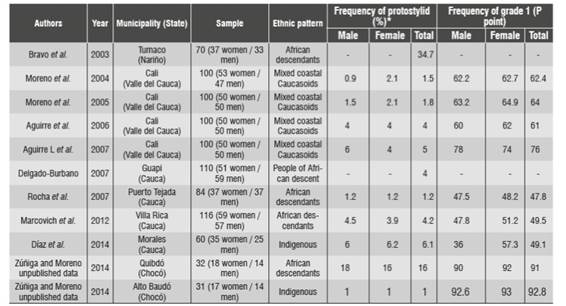

11 articles were finally selected as they met the inclusion criteria. Information on these 11 articles is listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Prevalence and variability of protostylid in populations from Southwestern Colombia

* The ASUDAS reference plaque has eight grades (0-7), with a dichotomous expression that considers the two first grades (0-1) as absent and the remaining six (2-7) as present.

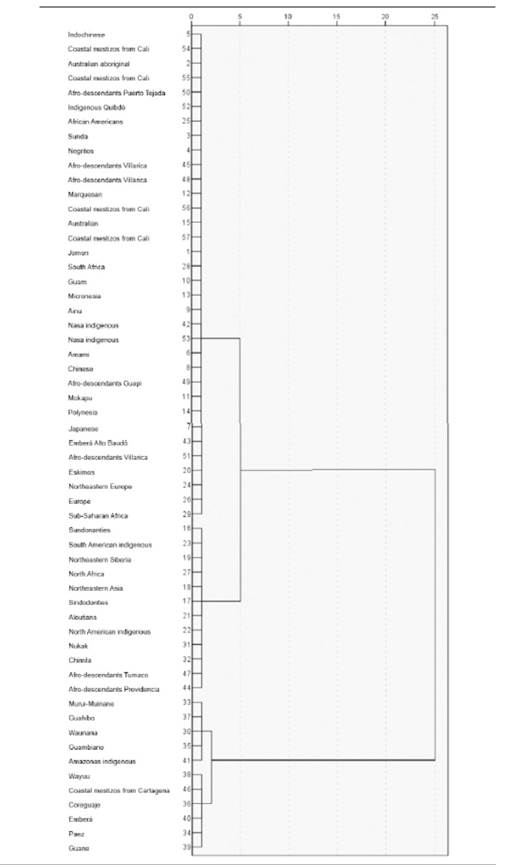

According to the prevalence and variability of protostylid in global populations, including those of Southwestern Colombia, it was noted that, according to the dichotomous expression, this DCMT is practically absent from samples of the studies considered in this systematic review. With regard to biological distances, the dendrogram contrasting the populations of these studies shows that the first cluster gathers the majority of populations, while the second and third clusters include two Africandescent populations (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Dendrogram obtained from distance matrix through the prevalence of protostylid in Southwest Colombian populations.

The dendrogram contrasting the 11 populations taken into account in the present study against different world populations shows that the first cluster includes the Mongoloid, Sundadonty, Caucasoid, septentrional, and southern West Africa and sub-Saharan populations, as well as contemporary Americanoid populations, which have high levels of groove expression (ASUDAS grades 2 and 3). The second cluster includes Mongoloid, Sinodonty, and meridional Caucasoid populations, presenting high expressions of groove plus blunt vertex cusp (ASUDAS grades 4-6), and expressions of groove plus free vertex cusp (ASUDAS grade 7). And the third and fourth clusters include indigenous Colombian populations, much closer to the second cluster due to their tendency to expressions of groove plus blunt vertex cusp (ASUDAS grades 4, 5 and 6). However, it is worth noting the high frequency of expression in fossa or P point (ASUDAS grade 1) (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Since frequency and variability of DCMTs allow associating human populations and geographical distribution, several researchers have ethnographically classified humans into population complexes-or dental complexes-based on dental morphology. The first of these complexes was defined by Hanihara19)(20 as the Mongoloid dental complex, which gathers different populations of Eastern Asia characterized by a complex dental morphology, represented in high frequency of groove expressions plus blunt vertex cusp, and groove expressions plus free vertex cusp of the protostylid.

Later, Turner II21 divided the Mongoloid dental complex into two groups. The first subdivision or sinodonty, composed of peoples from Northeast Asia, is characterized by the addition and intensification of some DCMTs including protostylid, showing high expressions of groove plus blunt vertex cusp, and expressions of groove plus free vertex cusp. The second subdivision or sundadonty covers populations of Southeastern Asia that have retained an ancestral condition and have simplified the expression of some DCMTs, including groove expressions plus blunt vertex cusp of the protostylid.

On the other hand, Zoubov22 proposed the dental classification of world populations into two complexes: the Eastern dental complex, which would correspond to the Mongoloid dental complex proposed by Hanihara, and the Western dental complex, consisting of septentrional Caucasoid and Negroid populations (meridional Caucasoid populations), characterized by a low frequency of protostylid represented in groove expressions. Irish23 subdivided the meridional Negroid populations from Africa (Western dental complex) into the North African dental complex (the same as the Caucasoid) and the sub-Saharan dental complex, characterized by groove expressions.

Edgar24 grouped humans into five conglomerates: the Mongoloid dental complex formed by sinodonty and sundadonty groups, the Caucasoid dental complex formed by groups of Western Eurasia (Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and India), the Saharan Africa dental complex (consisting of West African and South African subgroups, much closer to the sundadonty populations of the South Pacific), several groups of Sahul Pacific or Oceania, and the paleo-Indian Americans, showing frequencies and morphological variations that exclude them from the described complexes.

In the case of American populations, the model proposed by Turner II is currently accepted. This model suggests that peopling of the Americas initiated by sinodonty human groups who migrated from northern China and crossed Beringia,21 suggesting that all past and present American indigenous have a sinodont dental morphology; they should therefore be included in the Mongoloid dental complex, depending on their miscegenation with other ethnic groups.

The high frequencies of protostylid in groove expressions and blunt vertex cusp, as well as groove expressions and free vertex cusp would then substantiate the thesis of Northeast Asia as the origin of the first settlers of the American continent. To Zoubov,22 the high frequency of protostylid in its fossa or P point expression as a unique feature of the American populations allows suggesting the existence of the Americanoid dental complex, consisting of all paleo-Indian American and the contemporary populations descending from them.

Concerning the Colombian population, studying dental morphology and its association to the analyzed dental complex becomes difficult due to the ethno-historical processes that have taken place in the country. Rodriguez25 suggested that ancient indigenous populations were characterized by a high frequency of protostylid, represented in groove expressions and blunt vertex cusp, as well as groove expressions and free vertex cusp, along with the expression in fossa or P point, making them closer to the paleo-Indians descending from the sinodonties of the Mongoloid dental complex.

However, in the case of contemporary indigenous populations, the situation varies basically due to the mixing occurred with the arrival of Northern Caucasoid human groups coming from Western Europe (Western dental complex), who populated the American territory on three subsequent historical processes known as Discovery, Conquest, and Colony. These groups were characterized by a very simplified dental morphology, including high expression of fossa or P point, low grove expressions, and minimal groove expressions plus blunt vertex cusp.

León y Riaño26 analyzed several current indigenous Colombian populations, obtained by the Human Expedition of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá. The results showed high frequencies of protostylid in groove expressions, and groove expressions plus blunt vertex cusp. In comparing some DCMTs between a group of Andean mestizos and Embera indigenous populations, Ceron27 noted that the latter present high frequencies of groove expressions plus blunt vertex cusp.

Similarly, during this historic process, Negroid people groups (southern Caucasoid peoples from the Western dental complex) were brought as slaves to the Americas and were distributed in different regions of Colombia; this and the macroevolutionary process that took place in numerous migrations, contacts, and isolations, allowed the multiethnic, multicultural, and polygenic nature of the Colombian population.

Perhaps Southwestern Colombia is the region where these processes were more accentuated and is also the region with the greatest amount of studies in populations described as Caucasoid mestizos, indigenous, and Afro-Colombian. The Universidad del Valle School of Dentistry and the School of Health Sciences of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana at Cali have studied several populations in Southwestern Colombia (the states of Chocó, Valle del Cauca, and Cauca), concluding that the frequency of DCMTs is due to the process of historical miscegenation and to the dominance of these phenotypic expressions to the extent that a group of mestizos from the city of Cali is characterized by a simplification of dental morphology, given the absence of protostylid expression, along with the high frequency of expression of fossa or P point, suggesting the existence of interbreeding with indigenous Colombian populations.28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34

Similarly, in studying two Afro-Colombian groups from the state of Cauca-one in Puerto Tejada31 and one in Villa Rica32- and one group from the state of Chocó (unpublished data), low frequencies were observed in terms of grove expression of protostylid (a characteristic of the Western dental complex), but there was a high frequency of expression of fossa or P point, suggesting the existence of interbreeding with indigenous Colombian populations.

Concerning the Afro-Colombian populations, Delgado-Burbano33 indicated that these populations descend from Africans who came to the continent as slaves from Western, Central-Western (Sub- Saharan), Southeastern, and Northern Africa, all of whom are classified in the Western dental complex (Meridional Negroid), whose protostylid expressions primarily occurs in groove and blunt vertex cusp.

In studying Nasa34 and Embera indigenous populations (unpublished data), one may say that they have high frequencies of DCMTs that are typical of the Mongoloid dental complex; in terms of protostylid, there are high expressions of fossa or P point, and minimum expressions of groove plus blunt vertex cusp, which directly relates them to the sinodonties, just as other Colombian and American indigenous groups. These findings are consistent with those by Turner II21, Hanihara35, Zoubov,22 and Rodriguez,25 and also agree with the theory of Mongoloid origin of the indigenous peoples of South America.

However, the low frequencies of expressions of groove plus blunt vertex cusp, as well as low expressions of groove plus free vertex cusp of protostylid suggest the influence of contemporary Caucasoid and Negroid groups.

The current global trend to protostylid expression in different world populations of sinodonty origin (Mongoloid dental complex) tends towards grades 3 and 4, which show transverse grooves originating in the groove of vestibular development, in mesial direction, associated with slight blunt vertex cusps on the vestibular surface of the mesial-vestibular cusp of first lower molars. However, and despite this gradation, it is worth noting the simultaneous expression of a fossa in the cervical-most end of such groove of development, compatible with the foramen caecum, which would be the equivalent to the ASUDAS grade 1 which is described as the P point.

Therefore, one single tooth may express grade 1 along with another level of gradation. In contemporary populations of Southwestern Colombia (basically coastal mestizo Caucasoid, indigenous and Afro-descendant Colombians), the prevalence of protostylid has virtually been absent, according to the dichotomous expression defined by the ASUDAS system, but the high prevalence of grade 1 stands out, as its expression in fossa or P point occurs in the absence of protostylid (grade 0) and when protostylid is present (grades 3-7) even in the rare expressions of blunt vertex cusps and free vertex cusps.28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34)(36)(37.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the frequency of protostylid in permanent lower first molars, it is possible to conclude that the Southwestern Colombian populations taken into account in this study validate the classification by J. V. Rodríguez according to geographical location and ethno-historical processes, and therefore the dendrogram allowed to observe the grouping of populations in clusters corresponding to the three dental complexes established by Hanihara, Turner II, and Zoubov.

Miscegenation processes have then influenced the frequency of protostylid, decreasing the expression of groove, blunt vertex cusp, and free vertex cusp in indigenous groups, and increasing the expression of fossa or P point in populations of coastal mestizos and Afro-descendants. However, protostylid itself is not a discriminator of DCMTs in population groups from Southwestern Colombia.

This demonstrates that the expression of fossa or P point (ASUDAS grade 1), associated to the cervical fossa of the mesial-vestibular development groove in permanent lower molars can be expressed when protostylid is absent (ASUDAS grade 0), or when it is present in groove expressions (ASUDAS grades 2-3), groove expressions plus blunt vertex cusps (ASUDAS grades 4, 5, and 6), and groove expressions plus free vertex cusps (ASUDAS grade 7). This is why it is suggested that the presence of foramen caecum among Americanoid populations, including populations from Southwestern Colombia, is not dependent on protostylid expression, so the expression of fossa or P point described by ASUDAS is not homologous to the foramen caecum initially described by Miller.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Colombia is known as a multicultural, multilingual, polygenic country whose diverse population makes it difficult not only to conduct classifications in demographic censuses (geographical space and territory, common biological heritage, language and cultural traditions, ethnicity and identity) and socio-economic projections, but also in forensic procedures including the basic quartet of identification or general osteobiography (sex, age, stature, and racial pattern), as well as identification of macro-evolutionary development based on processes of peopling (migrations, contacts, isolations, and miscegenation) the Colombian territory. This population includes the Caucasoid mestizos (both coastal and Andean), indigenous peoples, people of African descent and rom peoples or gypsies.

Considering that several researchers have ethnographically classified human beings into populations complexes based on dental morphology, that the term dental complex refers to characterizations of large population groups, in accordance with specific combinations of frequency and variability of DCMTs, and that all modern human groups have the same amount of such traits in both dentitions, the scientific community interested in dental anthropology-specifically dental morphometry- is encouraged to: 1. Collect significant samples randomly selected from populations of different geographical regions of the country; 2. Use the ASUDAS system; 3. Rely on an equitable number of subject samples from both sexes, and 4. Include as many standardized DCMTs as possible

text in

text in