INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer causes severe consequences on people′s health, producing physical and functional deformities and mutilations that seriously affect the patients′ psychological, economic, social, and family contexts, as well as their quality of life in general. One of the most common expressions of oral cancer is squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), a malignant neoplasm resulting from stratified flat epithelium,1)(2) which is scarcely known and is associated with genetic and exogenous factors such as diet, alcohol consumption, smoking, and sun exposure.3) It is widely accepted that tumor location, its clinical stage and treatment type, among other variables, affect patient survival because of its ability to produce significant anatomical and physiological effects in those who suffer from it. (4

Prevalence, incidence, and mortality by OSCC vary widely in different parts of the world, with a high incidence rate in India and South Africa and low frequency in Japan and Mexico, with the aggravating factor of a significant increase among young people5) The literature indicates that a high percentage of OSCC patients are diagnosed in advanced stages (usually stage IV), with an evident decrease in survival probabilities.6) In Colombia in general, and in the city of Medellín in particular, studies including aspects related to OSCC patient survival are scarce. A report from the city of Cali suggests a relative survival rate of 55.5% in five years (CI 95% 50.9-59.9).7

It is therefore necessary to estimate survival rates of OSCC patients from their first treatment (in this case, the estimation was performed in cancer centers in Medellín, Colombia, in the period 2000- 2011) and to explore associated factors, providing prevention and early intervention strategies in order to reduce mortality.

METHODS

This article describes the experience of survival analysis based on a dynamic retrospective sample of OSCC cases treated for the first time in nine specialized cancer centers in Medellín between 2000 and 2011. With the approval of the participating institutions, the authors analyzed the medical histories of patients diagnosed with OSCC as a primary tumor (codes C00 to C06, C10 and C14 of the International Classification of Diseases, version 10, ICD 10), which allowed selecting OSCC patients based on histopathological confirmation, who had been treated for the first time in the nine specialized cancer centers. The medical histories of patients who had received any phase of OSCC treatment at a cancer center outside Medellín were excluded. Information about participating patients was obtained by first reviewing their clinical histories; if this showed that the patient was dead, indicating the cause and date of death, the information that was relevant for the study was collected. In some situations, when there was information of some patients who had died but whose clinical history included no death certificate, their families were contacted in order to find out the cause and date of death. In cases where the medical histories did not report their condition, the patients of their families were contacted in order to collect relevant information. In total, out of the 1700 medical histories manually reviewed, 630 patients were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria. It is worth mentioning that, in the case of living patients, the variable "date of last contact" was created based on information from the last date recorded in their medical history or from phone calls; in the case of deceased patients, the date of death included in the death certificate was assumed. Patients whose families reported not having access to a death certificate were assigned the latest date in which they were attended in the institution. Patients whose status was not possible to validate were assigned the latest date of contact with the institution. The variable "monitoring time" in months was calculated by differentiating the last contact date from the date of first treatment, the condition of no censoring was defined as patient death because of oral cancer during the study period. The data collection instrument was improved based on the suggestions resulting from the pilot test.

Information was recorded in a retrospective manner, taking into account the epidemiological variables of person, time, place, and clinics. Observer bias was controlled with advice by a head and neck oncology surgeon and a maxillofacial surgeon with experience in oral cancer; these two surgeons played a vital role in the instrument design, especially concerning clinical variables. The participating institutions approved telephone contact with all patients and their relatives, in order to verify whether patients were alive or dead. In the latter case, families were requested a death certificate, in order to find out the date and cause of death. This allowed avoiding information and selection bias. A standardized conversation script was used for telephone conversations, which was approved by the bioethics committee of each institution, in order to control information bias. Data were prepared by means of the available procedures, such as error typing detection, declaration of lost values, and variable cross-validation in order to observe the consistency of data related to the study variables. It is worth mentioning that this study defined a single medical history as the result of the compilation of information obtained through review of multiple histories of the same patient, from date of first treatment to date of death.

The statistical analysis was performed by means of the classical univariate indicators of survival. In order to assess the likelihood of patient survival in a given period of time ranging from the moment they were treated for the first time, we used the Kaplan- Meier method and the bivariate examination of survival using the relevant variables, which required implementing the log Rank test. The multivariate analysis required the construction of an explanatory model of Cox proportional hazards, based on the variables that met the Hosmer Lemeshow criterion during the bivariate test, as well as those that the state of the art defines as plausible. The research and bioethics committees of the nine institutions approved the use of informed consent and telephone contact with patients and labeled this research as "risk-free" as it involved no intervention in individuals. The data was processed using version 18 of the SPSS software.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics and habits

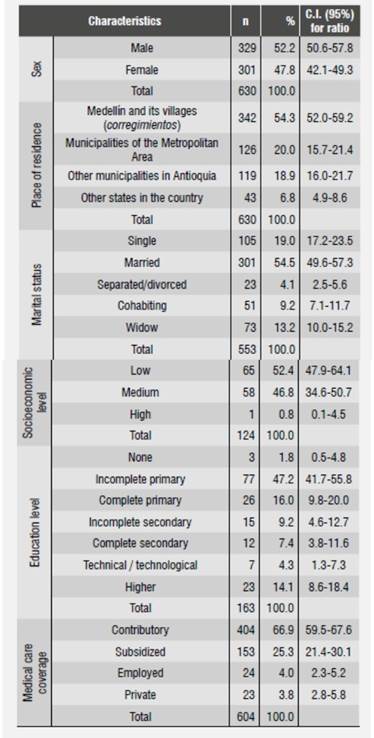

Average age at the time of diagnosis was 63.5 years (SD = 13.6 years). Sex distribution showed that 52.2% of patients were males. 54.3% of patients were originally from the city of Medellín, were they also resided; regarding marital status, 54.5% reported being married; 52.4% came from lower social levels, and 47.6% from medium or high social levels. 26% of patients provided information on their education level; 63.2% of them reported having primary education. As for social security coverage, most patients (66.9%) belonged to the contributory regime as either primary contributors or beneficiaries, followed by 25.3% who were covered by the subsidized regime (Table 1). Out of 546 patients, 45.4% of males were smokers, compared to 27.8% of females, but there was no statistical association (p = 0.168); out of the women who said they smoked cigarettes, 7.2% did so in an inverted manner, that is to say, with the flame inside the mouth, especially those residing in the states of Chocó, Sucre, and Cordoba. None of the men participating in this study referred practicing that type of smoking. In terms of alcohol consumption by 425 patients as stated in their medical histories, 29.1% of men used to drink alcohol compared to 5.6 percent of women, with statistical association (p = 0.000).

Clinical characteristics of patients

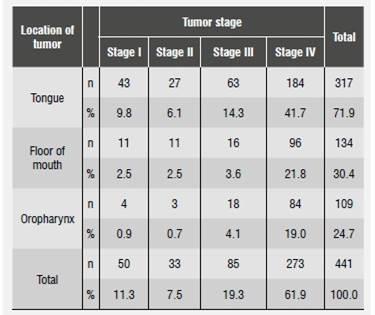

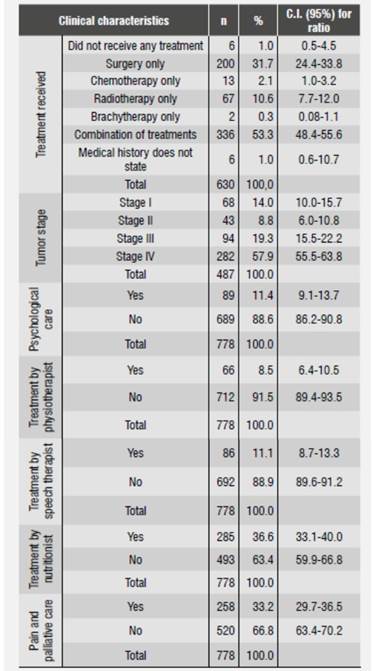

The most frequent anatomic locations of tumors were the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the oropharynx (56, 25.4 and 23.1%, respectively); the distribution of OSCC stage according to location in a single anatomical location indicated that the three abovementioned locations were the most prevalent and were treated for the first time when patients were in stages III and IV (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of oral cancer patients treated for the first time in cancer centers, Medellín, 2012

Characteristics of treatment

In total, 53.3% of patients received a combined treatment, as shown in Table 2. The most frequent single treatments were surgery (31.7%) and radiotherapy (10.6%). 4.5% of patients did not receive any treatment. When comparing distribution of treatment and disease stage, we found out that 50% of patients who did not receive any treatment had been diagnosed at stage IV.

In relation to the comprehensive care that patients should receive, 79.8% on average were not referred to other professionals. Those who received additional support were remitted mainly to nutritional care and pain and palliative care (Table 2).

Factors related to patient survival

Out of the analyzed patients, 28.1% (177) died because of OSCC. The median survival rate was 6.1 years (Interquartile Range = 1.6 years); 50% survival time was 6.1 years or less. From the moment of first treatment to before the first 11 months, the cumulative probability of survival was 83%, and about two years after first treatment, this cumulative probability dropped by 20%. Five years later, the cumulative probability of survival by OSCC from the first treatment decreased gradually up to 54%, and from this moment on it behaved in a similar manner.

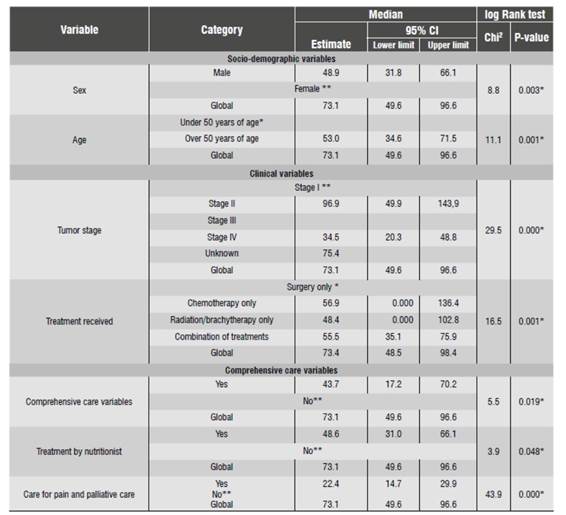

Statistical differences of patient cumulative survival time were found from the time of first treatment until death by sex, age, stage of tumor, and treatment received, being higher in women, patients younger than 50 years, patients diagnosed at stage I, and those who received surgery as single treatment (p = 0.003, 0.001, 0.000, and 0.001 respectively). Similarly, there were survival rate differences among those who received psychological care, nutritional care, and support for pain and palliative care (p = 0.019, 0.048 and 0.000 respectively). On the other hand, the analysis of clinical variables and treatment showed that the median survival rate varied significantly by tumor stage and treatment type: in the first case, there was an inverse relationship, i.e., the higher the stage the lower the survival probability; in the second case, patients who received surgery as single treatment showed a greater median survival rate than those with any other individual or combined treatment (Table 4).

Joint factors related to survival from the time of first treatment to death

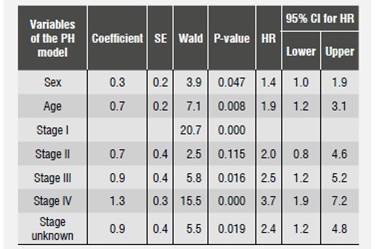

Once compliance of proportional hazards were demonstrated, we found out that patients under 50 years old had greater survival rates compared with those older than 50 years, and that being a male represents 1.4 times more risk of dying by OSCC compared to being a female. In terms of tumor stage, we observed that the risk of dying (HR) by oral cancer increases when stage is higher; for example, the risk of dying of a patient diagnosed at stage IV is 3.7 times (CI:1.9-7.2, p = 0.000) compared with someone who is diagnosed at stage I. All other variables remained constant (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Analyzing a sample of patients diagnosed and treated for OSCC in a period of 12 years (2000-2011) and gathering information for more than half of them from the perspective of survival time allowed us to assess survival rate. Many studies conclude that oral cancer is a chronic disease that primarily affects people older than 65,6as the present study confirms.6)(8

In the present study, the proportion of oral cancer was similar by sex, although some studies suggest that it is higher in males, which could be explained by their types of job;2)(9however, it has been reported that this ratio has been becoming equal, which is explained by changing social behaviors such as increased cigarette and alcohol consumption among women.10)(11Inverted cigarette smoking is considered a risk factor for oral cancer; in this study, 11 women had this characteristic.(3)(5)(12)(13)(14

Patients in this study come mostly from medium and low socio-economic levels, and their maximum education level is primary school, agreeing with several studies which suggest that the most vulnerable population is the one with little education, as it influences self-care for oral health and nutrition, both of which are considered risk factors for oral cancer. 14)(15)(16

In general, the literature reports that oral cancer is diagnosed at advanced stages,17)(18 which is consistent with the data from the analyzed sample, where most patients had a stage IV diagnosis,19)(20) with the tumor lesion located in one place of the mouth, being the tongue the most frequent site, followed by the floor of the mouth and the oropharynx.3)(6 Surgery is the primary treatment,6) despite the fact that in most cases it affects patient′s physiognomy and voice and is considered as aggressive, invasive, and mutilating. In addition, the time between diagnosis and first treatment (for patients whose medical records included this information) was three months, which is lower than the time found in Lopez′s study (1999), in which this disease′s evolution time until treatment averaged 8.5 months.6) A study conducted in 2012 in Manizales, Colombia, on different types of cancer, including that of the oral cavity, found out that patients were treated in average two months after feeling the first symptoms;21this suggests that oral cancer is detected and treated at a later stage, which is not consistent with good clinical practices. 21)(22)(23)(24

Overall survival rate at 5 years is 54%. This result is similar to that of other studies, in which survival rate was 50%,25and to another study which assessed the prognostic factors reporting a survival rate of 43 to 61%.26) Survival was higher in women, in patients under 50 years old, in those who were diagnosed in stage I and in those who received surgery as single treatment. Survival is highly affected by tumor stage; the higher the stage the higher the likelihood of death, which is consistent with studies on the tumor stage as a biological possibility of prognostic factor. 3)(17)(27)(28)(29)(30)(31

Limitations of the present study include the impossibility to check death certificates in government institutions against information from medical records, which reduced the number of patients included in the analysis. In addition, tracking patients through phone calls makes it difficult to analyze the actual phenomenon, requiring the cooperation of government bodies such as the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE) to access information of underlying causes and date of death. Another major limitation of this study is that the institutions′ information systems are not designed nor intended for health research, substantially limiting the collection of data on variables that can influence the different phenomena that are of interest to epidemiology; notably, the clinical histories showed an inadequate classification of the disease according to the ICD- 10 by the institutions, creating information bias that goes beyond researchers′ control.

Finally, these results may help health institutions in developing communication and educational strategies on prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of oral cancer in order to reduce the main risk factors that make of this disease a public health problem. Similarly, the results allow health institutions to document oral cancer patients′ survival rate, to have a more systemic view, and thus to strengthen their capacity for comprehensive care offered to patients and their families. Early diagnosis prevents patients from getting to an advanced stage of the disease threatening their physical integrity; and in terms of the institutions, timely attention allows a better use of resources, as they won′t need to invest in expensive treatments and will prevent lawsuits that affect institutional image. It is recommendable to implement a program of oral epidemiological surveillance since childhood at the local, regional, and national levels, allowing to observe and identify priority health problems, to evaluate interventions and to reevaluate the traditional view that oral diseases include tooth decay and periodontal disease only; In addition, non-dental professionals in the health care system must be sensitized to promptly refer patients with lesions and associated risk factors, as well as those who do not have such risk factors, as many diseases of the mouth are also seen by medical doctors, nurses, and other professionals who just prescribe anesthetics or mouthwashes.

In this situation, dentistry schools are encouraged to recognize that the role of dentists is a determining factor in early detection. They should be trained to contribute to the solution and monitoring of this type of disease. The government has formulated cancer policies; however, political will is required in order to achieve the goals stated, reducing incidence and mortality, and increasing survival rate and patients′ quality of life.

texto em

texto em