INTRODUCTION

Hemostasis is a series of mechanisms that contribute to stop bleeding and at the same time reduce blood loss. It involves three mechanisms defined in the literature as: vasoconstriction, primary hemostasis (adhesion and aggregation), and secondary hemostasis.1

Oral anticoagulants are one of the antithrombotic of greater interest and application in primary care, along with antiplatelet agents and lowmolecular- weight heparins.2) These medications act as vitamin K antagonists, inhibiting coagulation 3) and influencing the coagulation cascade, known as secondary hemostasis.4) This cascade is defined as a sequence of reactions seeking clot formation4 and act in a two-fold way: extrinsic and intrinsic, which make up the common pathway resulting in crosslinked fibrin, which is the one that forms clots.5

This can be seen in patients on antithrombotic therapy, who are controlled with the so-called parameter of international normalized ratio (INR).6) This implies calculating the ratio between patient′s prothrombin time and prothrombin time control, all this elevated to the international sensitivity index (ISI), which indicates the sensitivity of the thromboplastin used.7) This allows obtaining the standardized value of patient′s degree of coagulation, which is useful in medical and dental procedures alike.

While dental extractions are routine surgical procedures, in this type of patients it is necessary to pay special attention to bleeding degrees,6) following protocols prior to extractions, considering the following aspects:

1. Stop the anticoagulant therapy several days prior to surgery.

2. Replace therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin.

3. There is also the stance for maintaining the original therapy, but taking certain local measures for maintaining hemostasis.

These measures are aimed at minimizing bleeding risks at the time of dental surgery and afterwards.8

It should be noted that bleeding after dental extraction is easy to diagnose; in general, it is clinically self-limited and can be controlled with local measures, such as biting a gauze 9) or pharmacologically by means of tranexamic acid 8) or aminocaproic acid four times a day for at least two days.10

Currently there is no standardized approach to the management of these patients,11) but it should be noted that suspension or reduction of oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT) leaves them exposed, risking the appearance of thromboembolic events.12) This is why it is necessary to achieve a consensus on the management of these patients prior to minor surgery.

Given this debate, we conducted a systematic review by means of a meta-analysis, in order to establish the relevance of interruption (or modification) of anticoagulant therapy, mainly based on the bleeding degrees of patients using antithrombotic therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

This was a systematic review, consisting in structurally identifying controlled clinical research projects, evaluating studies with a common goal including a meta-analysis, which is a set of statistical techniques that combine the results of studies for global measurement parameters with clinical implications, focusing on recommending an evidence-based intervention.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following studies were included: controlled randomized clinical trials evaluating the management of patients on anticoagulant therapy, who had been subjected to dental extractions and whose therapy had been modified, replaced by another type of anticoagulant, or suspended days before the procedure.

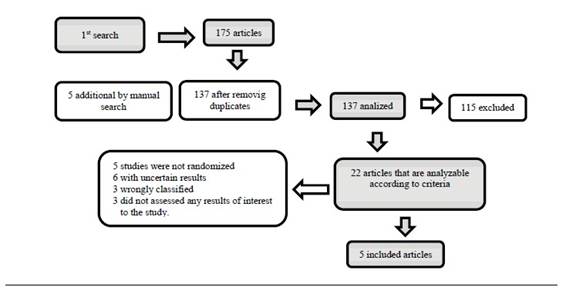

The following studies were excluded: studies whose information was not clear or accurate, both in terms of number of patients, the type of intervention they were subjected to, or the results in each group; studies involving a potential risk of bias were also excluded (Figure 1).

Literature search

The search was conducted by two researchers independently; disagreements were resolved by consensus by consulting an expert, who established the arbitration and final decision. Search engines specialized in biomechanical literature were used combining the following terms: dental extractions, anticoagulant therapy, hemorrhage, dental extraction, warfarin, acenocoumarol, antithrombotic.

Different databases were used: The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1990 to July 2012), Medline (via Pubmed) (1990 to July 2012), Embase (1990 to July 2012), Ebsco (1990 to July 2012), Google Scholar (with no time limits).

Data gathering

The initial search was conducted in Pubmed with the termsbleeding, tooth extractions, and anticoagulant therapy, yielding 175 articles.

According to study type, this search was limited to clinical trials, meta-analysis, and controlled randomized trials conducted in adult humans with no language restriction. After applying these limits, there were 22 articles meeting all criteria.

The second search was conducted with secondary terms such aswarfarin, bleeding, andexodontia, keeping the aforementioned limits. This search yielded 13 articles. A third search was carried out with the termsexodontiaortooth extraction, bleedingandantithrombotic; the limits were kept obtaining only one article.

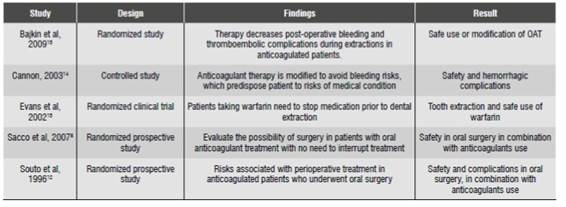

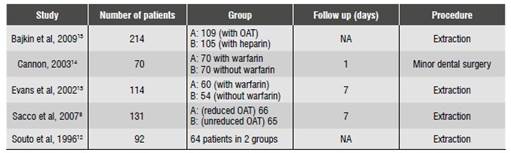

After comparing the articles yielded by all three searches, there were 25 publications in total. Twenty of these were excluded. Five articles were discarded because of their design type, ten because the subject was not in line with the object of study, and the other five because of methodological problems (Table 1), using the PRISMA®Guide, which assesses the clinical and methodological-statistical aspects (Table 2). Bias risk was also evaluated. Authors were contacted to obtain missing information. Only those articles with full information were used.

Statistical analysis

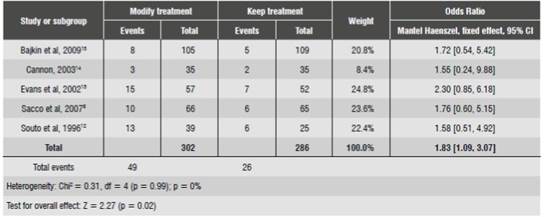

The statistical analysis was conducted using a randomized model. The Mantel Haenszel statistical method was used since it is normally applied in studies with small sample sizes and few events.

Heterogeneity was tested by Tau 2) with Chi 2/ test in addition to the I2 test, considering the values of 25, 50 and 75% as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity.16

If I2 is moderate, a sensitivity analysis is defined, evaluating the cause of the phenomenon. If it is low, the number needed to treat (NNT) is estimated in order to calculate the number of subjects required to perform the analysis.17

RESULTS OF THE META-ANALYSIS

The meta-analysis (Table 3) was conducted with the RevMan 5®software, obtaining an I² of 0% (heterogeneity), which is considered null.18) A value of 0.98 significance in the Chi 2) test, which shows the absence of heterogeneity among studies since the value is greater than 0.05, is required to confirm the presence of heterogeneity. This result validates the absence of heterogeneity in this study, since it is evident that all results point to keeping the therapy.

Three of five studies weighted more than 28% with short confidence intervals; however, all exceeded the line of no effect. This means that, in a low level, there were adverse effects when keeping the anticoagulant therapy. The two remaining studies weighted less, not exceeding 6%. The confidence intervals show they have a greater expansion, exceeding the line of no effect.

Summary measurement is in favor of the group that maintains therapy, regardless of some confidence intervals exceeding the line of no effect. Therefore, it is clinically recommendable to keep the anticoagulant therapy.

According to the aforementioned recommendation, it is important to bear in mind that patients on antithrombotic therapy who undergo dental extractions have increased risk of thromboembolism if treatment is interrupted, so it must be continued, since otherwise the risk of bleeding is increased.13) However, there are no evidences of severe hemorrhagic complications when dental extractions are carried out without modifying the intensity of treatment and maintaining INR.8) There are reports of fatal cases due to thromboembolic complications as a result of OAT interruption before extractions.

It is important to note that, according to certain studies, maintaining INR levels within therapeutic parameters is accompanied by a low risk of bleeding, and that this risk is lower than the thromboembolism risk resulting from treatment suspension.8

The antithrombotic therapy included warfarin and acenocoumarol within control groups,19) and patients with modified therapy received therapy bridge (nadroparin calcium),13) decreased dose of antithrombotic agent, or therapy suspension.19) In addition, bleeding levels following extractions were measured in all the studies; cases that developed major bleeding were considered relevant.

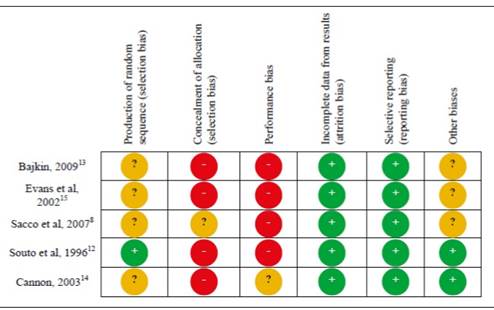

Bias risk in the included studies

The issue of bias risk was evaluated in each article. All articles lacked the information needed according to the guidelines of bias analysis; however, they could be overall evaluated (bias risk is shown in Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

According to the meta-analysis results, the suspension of antithrombotic therapy does not guarantee the absence of severe bleeding after extractions. This was demonstrated in the studies by Sacco et al, 2007,8) Souto et al, 1996 12) and Bajkin et al, 2009.13) In these studies, the group of patients who had their anticoagulant therapy changed or suspended developed more events than the group where it was constantly kept; these studies had the greatest weight in the analysis.

Of all the studies included in the meta-analysis, there were 553 patients in total, who were divided into two groups. 285 patients were selected for the group which had the therapy modified, with a total of 35 patients who had hemorrhages. A total of 268 patients were included in the group that kept the treatment (control group) and only 18 patients developed hemorrhages.

INR values 1) ranged from 1.5 to 3.4. Means of hemorrhage control included resorbable sutures,19) hemostatic sponges,13) and tranexamic acid 9) locally applied and as a mouthwash for 2 days every 6 hours.8) These measures were mainly taken in groups that kept the treatment. All patients had to bite sterile gauze for at least 10 minutes after surgery in order to control bleeding.

In all studies, the follow-up period was 6 days after surgery, a period in which all the bleeding events occurred, all of low to moderate intensity.

No thromboembolic events were found in patients under study, since the follow-up period was very short as to detect these events; in addition, sample sizes were small.

The INR2 values in accordance with patients′ pathologies range from 2.0 to 3.0, being even higher (3.5 to 4.0) in patients with acute myocardial infarction or heart valves. In addition, these values need to be constantly monitored, with no need to interrupt therapy for surgery.20) Concerning local hemorrhage control, Blinder et al (2001) compared three local measures in anticoagulated patients using silk sutures, hemostatic sponges, and tranexamic acid, finding out that there were no significant differences between the groups that interrupted therapy and the one that kept it. Therefore, the local standard and additional measures are effective for hemostasis in anticoagulated patients undergoing dental extractions.21

There are reports of serious embolic complications (including death), being three times more likely to occur in patients with hemorrhagic complications associated to anticoagulation and whose anticoagulant therapy was interrupted.22) In a study on bleeding and post-operative thromboembolism, around 20% of cases of arterial thromboembolism resulted in death of patient and 40% in permanent disability, compared with only 3% of cases of postoperative bleeding that were fatal.6

In conclusion, in comparing the suspension or modification of anticoagulant therapy with the continuity of it in patients undergoing dental extractions, the development of hemorrhagic events is not significantly greater, so there is no need to interrupt therapy prior to surgery, thus maintaining patient protection against possible thromboembolic events.

In cases in which INR levels are ≥ 4.0, constant monitoring is required in order to avoid possible bleeding of greater severity. It is necessary to unify knowledge among professors in the dental area, in order to bear in mind the necessary measures when treating such patients.

This study cannot be extrapolated to all types of dentoalveolar interventions, since the studies were mostly conducted in dental extractions.

text in

text in