INTRODUCTION

Mandibular asymmetry is associated with the core of condyle growth, which can directly or indirectly regulate the size of the condyle, condylar neck length and the length of the ramus and mandibular body. Its severity is linked to the time it started and its duration. However, the asymmetry may be reduced due to compensatory growth in adjacent bones.1) Deviations in mandibular condyle growth can affect functional occlusion and appearance of facial aesthetics.2) The reasons for these deviations in growth are numerous and often involve malfunction at the cellular level.3

The pathological conditions are subdivided into: a) congenital malformations linked to growth disorders (hemifacial microsomia), b) acquired disorders or trauma with related growth disorders, and c) primary growth disorders (condylar hyperplasia).3) We will describe each condition next.

First, hemifacial microsomia is caused by genetic factors. These anomalies include underdeveloped supraorbital ridges, negative slope of the palpebral fissures, hypoplasia of the malar bone or the mandibular rami and the condyles.4) It occurs unilaterally with deficiency in or complete absence of condylar growth, resulting in progressive facial asymmetry.

Acquired disorders include Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA), which is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology which starts before the age of 16.5) Although its etiology is still unknown, its features are clearly autoimmune. This disease is characterized by varying degrees of joint inflammation, destruction of joints and progressive disability.6) Affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), JIA is associated with characteristic facial changes, in particular with short mandibular ramus and a clockwise rotation of the mandibular body, an outstanding antegonial point and mandibular retrognathia.7)(8)(9)(10)(11) Another possible cause of mandibular growth disorders, of rather recent appearance, is an abnormal position or displacement of articular disk. Some authors suggest that disk displacement itself has an adverse effect on condyle growth. On the other hand, adverse effects on condyle growth can also be the consequence of an alteration of the masticatory function.12

Secondly, in mandibular trauma during childhood, the condyle region is affected in 36 to 50% of subjects. The consequences of trauma in the condyle will depend on its location. In the case of intracapsular fractures, there is an increased risk of ankylosis, especially in children under 3 years of age.13) If the fracture affects the neck of the condyle and is therefore extracapsular, the condyle head is often dislocated, almost always in a forward and medial direction.3) The long-term complications of intra- and extracapsular fractures, such as development of facial asymmetry or mandibular retrognathism and anterior open bite, as well as ankylosis of TMJ or painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD), seem rare.11)(12)(13)(14

Thirdly, condylar hyperplasia is characterized by excessive and progressive growth affecting the condyle, neck, body, and mandibular ramus. It is a self-limiting deforming disease, because of disproportionate growth since before completion of overall individual growth that continues after it has stopped. Patients normally consult because of real facial asymmetry with mandibular deviation, malocclusion, and in some cases joint symptoms. Mandibular growth occurs in all three planes of space, but with dominance in any of them.15) Epidemiologically, it seems to have a similar incidence in men and women and in different ethnic groups. It is most common in patients from 11 to 30 years of age, without preference for the left or right side. The etiology of condylar hyperplasia is controversial and not well understood. Some theories suggest that it is caused by trauma, hypervascularity, infections, and hereditary/intrauterine factors. There are two patterns of condylar hyperplasia: hemimandibular hyperplasia and hemimandibular elongation.15

Hemimandibular hyperplasia is a term coined by Rushton.16) It is the pattern of vertical dominance with growth of the condyle, the neck, and the ramus, which are more protruding in the vertical direction, with prominent convexity of ramus and mandibular angle. As for the mandible body, it shows upright growth with deviation that reaches the middle line; there is no chin deviation and the lower edge of the mandible is positioned at a lower level than the unaffected side, which means inclination of the bicommissural line.17

Hemimandibular elongation is a term introduced by Obwegeser and Makek.17) It is the pattern of horizontal predominance, characterized by horizontal displacement of mandible and chin towards the unaffected side. There is no vertical increase of the ramus. The occlusal plane can be tilted upward on the unaffected side. Occlusion appears as contralateral cross bite, while the affected side creates displacement in mesial direction class III Angle, producing the displacement of the lower middle line.17)(18

Treatments to correct skeletal deformities in condylar hyperplasia patients differ, in particular on the age in which surgery must be done and the operation itself.19) Various treatment protocols have been published,20) but high condylectomy is thought to be one of the best treatment options21) because it is expected that removal of the top pole of the condyle would stop mandible growth in the affected region and would therefore provide stable longterm results combined with orthognathic surgery.22) The high condylectomy described by Henny in 1957 consists of remodeling the condyle head; this treatment stops the excessive and disproportionate growth of the jaw by surgical removal of the main site of mandibular growth. There is abundant evidence suggesting that high condylectomy combined with orthognathic surgery is a stable procedure, with very predictable outcome for the surgical treatment of active condylar hyperplasia.23

CASE REPORT

Female patient of 16 years and 3 months of age with no relevant medical history and history of previous dental treatments by TMD. Extra-oral examination shows evident facial asymmetry with mandibular deviation to the right and a convex facial profile (Figure 1). The intraoral photograph shows nonconcordant dental midlines; the bottom one is tilt 4 mm to the right and the existence of anteriorinferior crowding is mild. The lateral photo shows molar mesiocclusion and bilateral canine occlusion, mild overjet and overbite, and the presence of open cross bite in the right side (Figure 2).

Extra-oral photos and teleradiography profile. Front photo shows large facial asymmetry (left), with acceptable neck length and open nasolabial angle (center). Posterior rotational growth and light class II skeletal (right).

Photos of occlusion in centric relation of first intention, with acceptable left occlusion but par tial right reversed occlusion and large deviation of midline.

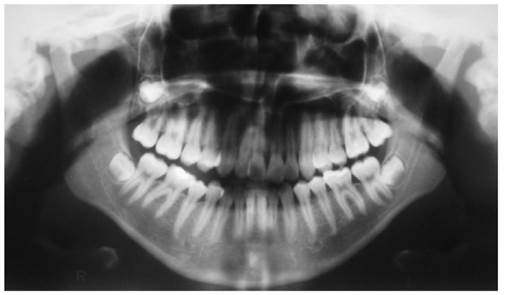

Additional examinations show, on the panoramic x-ray, the presence of permanent dentition, lower third molars in intraosseous evolution, and mandibular and condylar asymmetry (Figure 3). The teleradiographic analysis shows a dolichofacial biotype and class I skeletal (Figure 1).

Figure 3 Panoramic radiograph. Note the difference in mandibular angles and the shape of the condyles

Panoramic radiograph showing the presence of third molars in evolution, the asymmetrical shape of condyles and the size of the mandibular ramus.

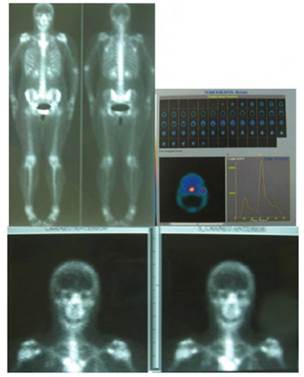

The patient′s bone scintigraphy showed a relationship of 1.29 between the two TMJs; total catchment of the right TMJ was 43.5% and 56.5% on the left one. This difference is greater than the 10% that is considered as active unilateral growth, which allows concluding that there is asymmetry in the TMJ osteoblastic activity, which is larger to the left side. This nuclear medicine examination is an exploration of the skeleton to detect bone metabolism. It uses technetium-99 along with methylene diphosphonate as phosphated radiotracer which is absorbed by hydroxyapatite crystals and calcium24) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Bone scintigraphy. The percentage of total catchment of the right TMJ is 43.5% and the left one is 56.5%. There is asymmetry in osteoblastic activity.

Bone scintigraphy showing more osteoblastic activity on the left TMJ.

The treatment plan included an initial surgical phase with high condylectomy followed by a second phase of orthodontic treatment. This procedure was performed according to the protocol of Walford et al published in 2002,23) which is an external incision followed by resection of the upper part of the condyle, as described by Olate and De Moraes.2) With this treatment, one month later the patient showed remarkable improvement of her facial aesthetics (Figure 5) remaining one year later. Her final occlusion is acceptable, with a slight relapse into class III on the right side.

Figure 5 Front photos comparing the results of high condylectomy at baseline, one month after surgery, and one year later

Photos of face at baseline (left) immediately after surgery (center) and one year later (left). Note the improvement in facial symmetry.

Figure 6 Occlusion arches in intermediate and final stages. Note the reduction in open bite after surgery.

Intraoral photographs immediately after condylectomy (above) and at the end of treatment one year later (below), showing proper neutrocclusion and a very slight lack of coincidence of midlines.

DISCUSSION

Condylar hyperplasia is a type of alteration of mandibular growth. Clinically, it appears as evident facial asymmetry plus mandibular deviation. Its etiology is controversial, with some theories suggesting that it is caused by trauma, hypervascularity, infections, and hereditary/ intrauterine factors.15) Different treatment protocols have been published, and one of the treatment choices that have been considered is high condylectomy, a procedure with fairly divided views among specialists.

Several research studies are in favor of high condylectomy, such as the studies by Poswillo in primates, which demonstrated the great capability of TMJ to recover after condylectomy.

The author showed that the condylar head is repaired with fibrous tissue, which later undergoes metaplasia to fibrocartilage of histological features similar to those of original tissue.25

A study published in 2002 by Wolford et al23 compared the results and stability of this treatment in patients diagnosed with active condylar hyperplasia treated with conventional orthognathic surgery versus patients treated with high condylectomy plus repositioning of joint disk combined with orthognathic surgery. The results showed a statistically significant difference, yielding a more stable result with high condylectomy and repositioning of joint disk. Condylectomy requires the effective elimination of 3 to 5 mm of condyle head, without causing adverse effects on the mandibular function in the longterm. Making high condylectomy combined with orthognathic surgery is a stable procedure, with a very predictable outcome for the surgical treatment of active condylar hyperplasia.23

In 2001, Oliveira-Junior and Faber26 found excellent results using Le Fort I osteotomy, sagittal osteotomy of unilateral mandible and condylectomy, associated with orthodontic treatment. In 1999, García et al27) presented clinical cases treated with condylectomy and reconstruction of TMJ with complete prostheses (condyle and fossa). In 2002, Wolford et al23) made a comparative analysis of two surgical methods noting that the most stable and predictable method was the one used in patients treated with high condylectomy, repositioning of joint disk and orthognathic surgery. In 2000, Ochandiano et al28) used condylectomy and repositioning of dislocated disK, fixing it with the Mitek system (minianchor) plus orthodontic-surgical treatment. Recently, Villegas et al29) reported a case that follows the same principles, but unlike our case they used an alloplastic graft with CAD/CAM technology to achieve face symmetry.

The protocol used is similar to that reported by Chiarini et al,30) who used the piezoelectric device for surgery in five patients between 2005 and 2012, and as in our case the postoperative problems were insignificant with this minimally invasive procedure.

CONCLUSION

In the literature, condyle hyperactivity is commonly referred to as condylar hyperplasia (CH), an infrequent disease described for the first time in 1836, linked with excessive growth of mandibular condyle. This disorder is usually unilateral, resulting in facial asymmetry and occlusal alterations, and may be associated with pain and dysfunction. It is usually treated surgically by means of a high condylectomy. The purpose of this surgery is to stop excessive and disproportionate growth of the mandible by eliminating the main site of mandibular growth. There is abundant scientific evidence that supports the use of this procedure for the management of active condylar hyperplasia; however, it tends to be very invasive. The clinical case presented in this article illustrates the excellent short-term results using a piezoelectric cutting device.

text in

text in