INTRODUCTION

Even though the scientific literature often addresses topics like the relationship between low weight at birth and the development of tooth decay, it has not yet defined the relevance of adding oral health care to the comprehensive care of children’s health in various contexts, starting with the prevention of early childhood caries (ECC).1)(2

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) defines ECC as the presence of one or more dental caries lesions, either cavitated or non-cavitated, lost teeth by dental caries, or sealed surfaces in the deciduous dentition of children under 71 months of age. S-ECC is described as dental caries in smooth surfaces in children under 3 years of age, presence of 1 or more decayed teeth, lost teeth due to dental caries or smooth surfaces sealed in anterior teeth by the age of 3 or 5 years, the presence of 4 or more surfaces sealed by the age of 4 or 5 years, the presence of 5 or more surfaces sealed by the age of 4, and the presence of 6 or more surfaces sealed by the age of 5.3

This condition is a public health issue usually overlooked in Colombia despite its high prevalence.4) in 2003, Saldarriaga et al,5) in a study in 86 children aged 3 to 5 at community homes of Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF), showed that dental caries in deciduous dentition is underreported in Colombia. They found a prevalence of 48% and concluded that the causes for underreporting include diverse diagnostic criteria, difficulties in approaching patients, caregivers’ cultural imaginaries, and barriers in accessing the health system.5 In 2011, Ramírez et al conducted a study in 659 children aged 1 to 5 years, attending children’s homes in the northeastern area of the city of Medellin, finding out that 69.7% of children of both sexes had experienced ECC, increasing from the first year to the fourth, with a higher prevalence in boys (71.6%) than girls (67.5%).6) The Cuarto Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal (ENSAB IV) reported that 38,27% of children aged 1, 3, and 5 had experienced dental caries and that by the first birthday 6.02% experience dental caries.7) These reports show that the situation of temporary dentition has not improved.

The clinical diagnosis of dental caries has traditionally been done based on cavitary lesions, overlooking records on the incipient lesions on enamel, which are an important indicator of the severity of lesions in the first years of life. Exploring the cultural beliefs that consider temporary dentition as a transitional nature and the absence of subsequent attention have been causal factors found in different environments.4) In addition, barriers of access to timely and effective health care to solve ECC issues are variables that help explain the lack of attention to a public health problem.6

The development of ECC includes several social factors and conditions of the oral cavity that determine its rapid and characteristic evolution, namely oral microbiology, dental calcification, eating habits, oral hygiene habits, and dental eruption pattern.8) The progression of lesions have local and systemic effects in the short and long term. Local complications include inflammation, infection, alterations in mastication, deficiencies in language development, alterations in the development of maxillaries, loss of space due to premature extraction, hypomineralization and hypoplasias in permanent teeth by chronic infectious processes in temporal teeth.8)(9)(10) Dental fissures and tooth decay in permanent teeth. may also arise.11

The associated systemic consequences include: neurodevelopmental insufficiency, learning difficulties, low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, aggressiveness, attention deficit, hyperactivity, psychological problems, sleep disturbances and gastrointestinal disorders caused by inadequate eating habits caused by toothache and coronal destruction, which interfere with mastication and food intake, influencing the alteration of the nutritional state reflected in anthropometric indicators.12)(13)(14

The American Academy of Family Physicians 15) recognizes ECC as the most common chronic disease in children under 6 years of age and encourages health professionals to carry out early detection and referral to the dental clinician, in addition to evaluate risks.16)(17

In consequence, the goal of this study was to determine the association between social and biological risk factors with early childhood caries (ECC) at community homes of the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF) in Zipaquirá, Colombia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To achieve the objective of this project, a cross-sectional descriptive study was designed and conducted. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Institución Universitaria Colegios de Colombia (UNICOC) and Universidad de la Sabana. It complied with the regulations established by Resolution 8430 of 1993 of Colombia’s Ministry of Health, which established the scientific, technical and administrative standards for research in health.

In a population of 3024 children attending community homes of the ICBF in thirteen municipalities in Zipaquirá, Cundinamarca, Colombia, 579 children were selected to form a sample stratified by municipality. The sample size was achieved using the following parameters: 64.7% expected prevalence (a value obtained in the study’s initial phase in the municipality of Chía, Cundinamarca), 95% significance level, and 3.5% expected error. Information was finally obtained from 546 (94.3% of the sample) children aged 24 to 60 months with complete temporary dentition, with no systemic diseases and with informed consent signed by their parents. The following children were excluded: children with permanent teeth erupted, showing health alterations at the time of examination, and those who did not consent the clinical examination.

A semi-structured instrument was designed for data collection; this instrument was used by the researchers. Guidelines for the implementation of that instrument were created, including 5 modules:

1. Socio-demographic variables (gender, age, parents’ socioeconomic level according to classifications by utility bills, level of education of main caregiver, social security coverage)

2. Oral hygiene habits (frequency of brushing, brushing time, supervised brushing or performed by an adult, visits to the dentist, dental treatment, age of first visit to the dentist)

3. Variables related to feeding habits and breastfeeding (if breastfeeding was provided and for how long, age of first use of baby bottle, time for baby bottle intake, use of sweetener in bottle, consumption of bottle or another type of food in the evening after brushing)

4. Dental examination (ICDAS, DMFT index, severity of ECC, O’Leary Index)

5. Medical examination (weight-for-length, overall Abbreviated Scale of Development [ASD]).

The presence of ECC in the study population was determined by dental examination with the presence of at least one of the following criteria: a) incipient lesion on enamel on a smooth surface in children younger than 3 years, b) presence of 1 or more decayed or lost teeth due to dental caries, or smooth surfaces sealed in anterior teeth at the age of 3 or 5, c) DMFT index equal to or greater than 4 at the age of 4 years, 5 at the age of 4 years, and 6 at the age of 5 years.3) An anthropometric evaluation was conducted to obtain the weight-for-length values (W/L). Each subject was classified in terms of their acute nutritional status as malnourished, normal, overweight, or obese, according to their scores in the W/L index, using the standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO).18

The neurodevelopmental evaluation was conducted using the Abbreviated Scale of Development (ASD), validated for Colombia by Ortiz, which assesses fine motor, gross motor, language-audition, and socialization. In addition, it provides a comprehensive indicator of the four areas. In each area, the subjects were classified per their scoring, according to one of the following categories: alert, medium, medium-high, and high. The “alert” state indicates an alarm on the achievements that should have been reached in this age group.19

The data were processed in the STATA 10.1 statistical program. The prevalence of early childhood caries and their severity was estimated based on confidence intervals. Measures of absolute and relative frequencies for the categorical variables were calculated. To evaluate the association between early childhood caries and severe caries with the evaluated variables the Pearson χ² test was used for categorical variables, and Spearman’s coefficient of correlation for ordinal variables.

RESULTS

Most kids in the study population were males (57.5%). Most children (83.1%) were 37 to 60 months old. 67% belonged to socioeconomic level 2 (on a scale of 1 to 6) and 51.8% were living in urban areas. There was a prevalence of ECC of 64.3% (95% CI 60.3%-68,3%) and a prevalence of S-ECC of 54% (95% CI 49.8%-58,2%). The median DMFT index was 2, with a range of 0-16. In terms ICDAS criteria, the prevalence of dental caries was 92%.

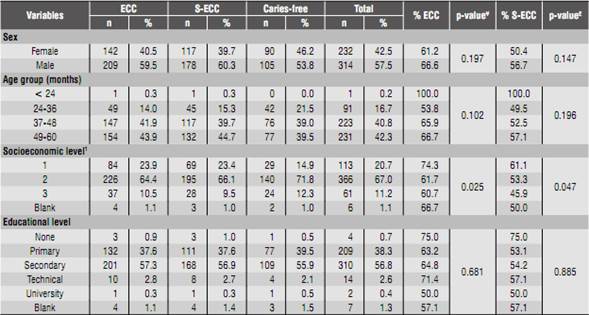

Table 1 shows the results of the tests of association between sociodemographic variables and ECC. Sex, age group, educational level and the type of coverage by the social security system showed no statistically significant association with ECC (p > 0.05).

Table 1 Percentage distribution of ECC and S-ECC according to socio-demographic variables

1 Socio-economic level: 1 low-low, 2 low, 3 medium-low, 4 medium-high, 5 high.

¥p-value for association between ECC and socio-demographic variables

£p-value for association between S-ECC and socio-demographic variables

Table 2 shows the results of ECC and S-ECC according to the variables of dental care and hygiene. A statistically significant association was found between ECC and visits to the dentist and treatment (p = 0.000). The age range for the first visit to the dentist was 24 to 35 months in 48.9% of the sample. For this age range, the prevalence of ECC was 69.7%. 1.2% of the sample did not perform tooth brushing and 98.7% had a plaque index (O’Leary) higher than 15%.

Table 2 Percentage distribution of ECC and S-ECC according to the variables of hygiene habits and visit to the dentist

¥p-value for association between ECC and variables related to oral hygiene habits

£p-value for association between S-ECC and oral hygiene-related variables

Table 3 shows the presence of ECC and S-ECC regarding breastfeeding practices and use of baby bottle. The use of baby bottle and the use of sweeteners in it were found significantly correlated with S-ECC (p = 0.027) and (p = 0.028) respectively. Statistical significance was also found in terms of variables “fall asleep with bottle in mouth” (p = 0.006) and “food intake in the evening after brushing teeth” (p = 0.043)

Table 3 Percentage distribution of ECC and S-ECC according to variables related to feeding practices

¥ p-value for association between ECC and variables related to feeding practices

£p-value for association between severe ECC and variables related to feeding practices

Table 4 shows the results obtained from the abbreviated scale of development and anthropometric variables. The scale showed a total of 17.8% of children in alert. There was association between this total result of the scale and the presence of ECC, noting that the alert group had the lowest percentage of ECC (p = 0.024). In relation to the weight-for-length indicator (W/L), nearly 20% of the sample is overweight, and the malnutrition group has a greater percentage of ECC in 73.3% (p = 0.034).

DISCUSSION

Among the 546 children belonging to the ICBF community homes in Zipaquirá there were prevalence levels of ECC and S-ECC over 64 and 50% respectively. As seen in other populations, dental caries in preschool-age children remains a problem, and the high percentage of S-ECC is even more worrisome, considering that if affects the quality of life and the risk of developing dental caries in permanent teeth.14)(20) According to the survey, oral hygiene habits showed that both mothers and children brushed at least 1 time a day in 68.8%, and the clinical examination yielded an O’Leary’s index of 98.7%. This shows that brushing has a different effect in each individual and its frequency does not necessarily result in effective removal of biofilm.21

The mothers’ oral hygiene habits were included because they replicate these practices in their children. Contrary to expectations, no association was found between EEC and O’Leary’s index, the habit of baby bottle, or the mothers’ educational level. However, the results of the present study are consistent with the literature, which shows that an improvement in health knowledge does not lead to long-term changes in behaviors. 14)(22

74.9% of the study group reported use of baby bottle, with a statistically significant association with S-ECC, hours of consumption of bottle in the night, sweetened bottle and the habit of sleeping with it. This same association was reported by Reissie and Douglas,23) Tinanoff 24) and Declerck et al.25) Dietary factors significantly associated with S-ECC are related to the frequency, time and amount of sugar consumption. In 1956, Schneyer et al 26) showed that bottle’s teat capacity and the antimicrobial saliva properties are closely related to saliva flow rates. Feeding practices including the frequent intake of sugars at night, when salivary flow decreases, produce an increased risk for EEC.27

Although 87.4% of the study population is covered by the General System of Social Security in Health (SGSSS for its Spanish initials), 59.9% of infants were brought to the dentist after the first year of life. They may be brought to dental consultation to receive a restorative treatment instead of a preventative one, agreeing with Finlayson et al.12) This condition can be the result of the parents’ lack of information about public policy and the strategies developed to care for the oral health as a contributor to the overall health in early childhood.28

As for evaluation in terms of the neurodevelopment abbreviated scale, the sum of the four areas showed a prevalence of 80%, which corresponds or is beyond the range of qualification. However, the prevalence of alert is 17.8%, with hearing and language being the most affected area. This means that about one in every five children in the study population requires assessment and detailed care by the social security network to ensure proper care, as well as a competent intervention addressing the existing neurodevelopmental alert. However, there is a statistically significant association between ECC and better neurodevelopmental scores.

In addition, early childhood caries affects the quality of life, and thus can influence children's behavior, agreeing with Abanto et al, who concluded that the severity of early childhood caries and a low socioeconomic level both have a negative impact on the quality of life of preschoolers.29

The high prevalence of growth and developmental alterations corresponds to avoidable actions with health promotion and disease prevention activities. It is also implies avoiding the worsening of detected conditions and that the potential consequences do not negatively influence the future adaptation to a form of autonomous and productive life. Defining these processes in an articulated and clear manner within public policies is a goal that contributes to the reduction of avoidable inequalities and which, combined with quality education, can lead to the generation of the necessary human capital for the development of society.

According to Franco 30) in relation to oral health, the various preventive and correcting programs have focused on the school population, ignoring the priority care needs of the population under 5 years of age. The socio-economically vulnerable population is most affected in terms of the presence of oral diseases, as well as difficult access to oral health services. It is also common for parents and primary caregivers to ignore the importance of the oral and dental conditions of early childhood population, due to the temporary nature of dentition.31

Is important to note the strengths and limitations of this study. This was a multidisciplinary team which allowed the comprehensive approach to the health problem of interest. It should also be noted that there was an unlikely possibility of incurring in selection bias, given the type of sample used. As limitations, despite sample size no causal relationships were established due to the study design.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The results of this study corroborate the relevance of ECC as a highly prevalent disease. In this study, ECC was particularly frequent in populations with low income and inadequate oral hygiene habits and visits to the dentist.

It is crucial to offer a comprehensive approach to the attention given to prevalent childhood health problems beyond mere survival, seeking to secure the right to developing the person’s potentials. Moreover, the education offered to caregivers should lead to the activation of a comprehensive system of intervention restoring the individual’s right to health and to the achievement of his/her biological capabilities.

texto en

texto en