INTRODUCTION

Angina bullosa hemorrhagica (ABH) was first described by Badham in 1967 as a disease characterized by vesicles or blisters containing blood, which are not attributable to blood dyscrasias, vesiculobullous disorders, or other known causes.1,2 In 1992, Scully gave a synonym for ABH, naming it oral purple also. Other names to this lesion include benign bullosa hemorrhagic stomatitis and traumatic or recurrent oral hemophiltenosis..3 Clinically, ABH is characterized by a single or multiple lesion, asymptomatic for their most part (but painful in some cases), appearing suddenly,3,4 with color ranging from dark red to purple, which can break and expand rapidly in a term of 24 to 48 hours;4 however, there are reports of cases lasting more than four months to years.5 It may appear as multiple blisters of two to three centimeters in diameter that break spontaneously and heal leaving no scars, although may be recurrent.6,7 It has no sex predilection, and the age it most frequently occurs is between 50 and 70 years;3 however, it can occur in younger patients.8

The most commonly affected area is the soft palate,3 although the literature has reported cases in other less common areas such as the buccal mucosa, the lateral border of the tongue,3 the anterior pillar of the jaws and the arytenoid cartilages;7 in fact, it has also been located in the area of the floor of the mouth and in the pharyngeal and esophageal mucosa;2,4 unusual cases have been reported in keratinized mucosa, such as the hard palate.9

ABH is not associated with blood disorders or hemorrhagicconditions;1,3,4 its pathogenesis remains unknown, and the most important related factor is local tissue trauma,1,3,6 caused by the consumption of hot drinks, dental procedures, harm to mucous membranes, or as a result of local anesthesia.2 Other conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and inhaled steroids, salbutamol and ipratropium bromide, appear in the literature as predisposing factors.3,4,5,6,7 Although its visual diagnosis does not represent a major problem, it is important for the clinician to differentiate it from other conditions, such as hemorrhagic disease or bullous disorders, that can show characteristics similar to this benign condition.1

The differential diagnosis is done against other hemorrhagic lesions, since ABH is similar to thrombocytopenia lesions, but blood count and hemostatic function are normal in the former. On the other hand, amylose produces hemorrhagic blisters, with systemic manifestations and tissue amyloid deposition in the skin. Occasionally, lesions by endoscopy procedures can resemble ABH.10

The treatment seeks to reduce the discomfort and to improve the ulcer’s healing after its eruption, as in most cases it tends to heal spontaneously.6 In the presence of large, intact blood blisters, an incision is recommended to prevent its extension, thus preventing the obstruction of airways. Its treatment has been defined as symptomatic, using mouthwash and painkillers and avoiding thick foods.7 In inhaled steroid users, gargling with water, followed by an application of medicine, have seemed to be a very effective way to prevent ABH onset.6 In cases in which ABH affects the soft palate and the blister has ruptured, it is recommended to use antibiotic prophylaxis and antiseptic rinses, such as chlorhexidine digluconate in concentrations of 0.25% or 0.12% to help reduce symptoms and prevent secondary infection. In areas less commonly affected, the clinician should evaluate whether antibiotic use is necessary. Chlorhexidine rinses are recommended for all patients.10 This article reports a case of ABH which appeared four months after a crown enlargement surgery performed to correct an altered passive eruption in a 21-year-old patient. Clinical characteristics are described as well as their respective management.

CLINICAL CASE

A 21-year-old patient with no relevant medical history at the initial examination seeks periodontal evaluation as she has short square teeth with high keratinized gingival band and sulci shorter than 3 mm, so she is diagnosed with type 1B altered passive eruption Figure 1. Lab tests are requested prior to the surgical procedure, since the patient reports not seeking medical or dental consultation more than two years ago, and the recommended surgical procedure is extensive and invasive; the tests results are all normal. The first step is the hygienic phase, providing the patient with strict oral hygiene instructions, as well as prophylaxis and use of ultrasonic magneto, in order to remove calcified plaque. The procedure of choice is crown lengthening surgery from the first right molar to the first left molar, in order to correct the altered passive eruption and improve patient’s aesthetics. Four cartridges of 2% lidocaine + 1:80000 epinephrine are applied, conducting the pre-surgery height and width measurements of initial clinical crown and the tooth size expected after the procedure, defining a blood point. The height of the keratinized gingiva and the depth of the sulcus are also measured to confirm the diagnosis. The surgical procedure consists of making an internal bevel incision from mesial of the first right molar to mesial of the first left molar, excluding the interdental papilla, from the mesial angle-line to the distal angle-line of each tooth. This is followed by an intracrevicular incision. The gingival collar is removed and an incision is made to divide the interdental papilla instead of completely remove it, in order to avoid its atrophy. Then a mucoperiosteal flap is elevated, performing osteoplasty to correct bony bumps and improve bone anatomy, as well as osteotomy to place the bone crest 2 mm from the cemento-enamel junction. Finally, root planing is performed, as well as the suture of the flap apically positioned. Post-surgery instructions are given in writing, prescribing azithromycin 500 mg, 1 a day for 3 days, and Nimesulide 100 mg 1 every 12 hours for 3 days Figure 2.

Figure 2 Crown lengthening surgery to correct the altered passive eruption and level the gingival zenith

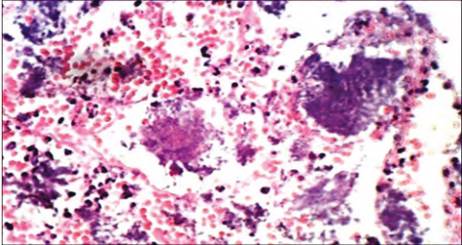

Stitches are removed ten days later, observing normal post-surgical healing. During a follow-up examination two weeks later, there are some swollen red areas by the interdental papillae of premolars and incisors, which were more noticeable between the premolars of the first quadrant and the central and lateral incisor of the second quadrant. One month later, the swollen area covers the margins of the abovementioned teeth Figure 3, and in the postsurgery, four months afterwards, there were some red defined smooth lesions of about 1 cm in diameter at the level of the first right and left premolar; the central incisors bled easily Figure 4 A, B, and C). The patient reports burning at consuming acidic foods and discomfort and bleeding at brushing. Biopsy of both lesions is performed, sending them to laboratory for histopathological study by oral pathologist. The histopathology evaluation showed an ulcerated epithelium with necrotic foci; the dense connective tissue shows an inflammatory infiltrate characterized by presence of lymphocytes and plasma cells. There are abundant polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) and some eosinophils; there are abundant extravasculated erythrocytes with ruptured capillaries. Numerous bacterial colonies can be seen in the periphery and inside the epithelium. There is no evidence of malignancy Figure 5. All this confirms the diagnosis.

Figure 4 Clinical image four months later showing the lesions at the upper posterior incisors and premolars after surgery. A. Image of the left upper posterior area. B. Image of anterior teeth. C. Image of the right upper posterior area. Localized lesions can be seen.

Scaling and root planing of the affected area were done as supplementary treatment, prescribing analgesic therapy. The patient’s postoperative period was favorable, and in a follow-up period of fifteen days she showed adequate evolution with no signs of relapse Figure 6.

DISCUSSION

ABH is characterized by the sudden appearance of a blister with blood on the oral mucosa, with no identifiable cause or related systemic disorder. While its etiology is still uncertain, it has been described as a multifactorial phenomenon, in which functional or dental trauma seem to be the most important risk factor.10

Luthra et al11 state that the causes reported in the literature are related to minor trauma, such as consumption of hot foods, dental restorations, periodontal therapy, endoscopic trauma, dental anesthesia injections, steroid inhalers, rinses of digluconate chlorhexidine, and snoring. In the present clinical case, after periodontal surgery the patient shows ABH during the postoperative period, suggesting that the trauma caused to the tissues during surgery could trigger its appearance.

According to the literature, the most common location of ABH tends to be the soft palate, as reported by Yamamoto et al12 in a study conducted in eleven patients who had ABH in this part of the mouth, either to the right or to the left side, or above the medium line; However, the same authors claim that, although this is the main affected area, it is not the only one. Other areas include the buccal mucosa, the lips and the lateral surface of the tongue. While the soft palate is the site most commonly affected, Pahl et al13 reported a case in which the junction of hard and soft palate was affected; in fact, this case also reported obstruction of the upper airway, which is not common and had not been reported in the literature so far. However, in contradiction to Yamamoto et al,12 who point out that the masticatory mucosa, the hard palate, and the gingiva are not affected, the present case shows that, after a surgical intervention (considered as local trauma), the vestibular marginal gingiva of several upper teeth was affected.

Even though the diagnosis of ABH is purely clinical, the patient’s systemic condition must be considered. Singh et al14 point out that a history of continuous trauma of the teeth to the mucosa may lead to a presumptive diagnosis of ABH; however, the differential diagnosis excludes cutaneous, mucous or blood pathologies, such as erythema multiforme, lichen planus, pemphigus, pemphigoid, thrombocytopenia, and Willebrand disease.

The case we presented led to a diagnosis of ABH, given the patient’s normal systemic condition, the normal laboratory test results, and the absence of any of the diseases listed in the patient’s personal and family medical record.

ABH is usually described as a unique lesion in the areas described by the authors; however, the lesions may be multiple as described by Patigaroo et al8 presenting a case of a twenty-eight year old patient with multiple hemorrhagic bullous lesions. The present case also had multiple lesions in the marginal gingiva of several teeth, all of which were surgically intervened.

Curran and Rives9 described the appearance of gingival ABH three to four days after scaling and root planing therapy in the gingiva adhered to the palatine side of the upper central incisor, a location that had not been reported to date. The characteristics given in that case report were: bullous high lesion of about 6 x 3 mm in diameter, which a few days later left a red, erythematous, ulcerated surface that healed with no scarring; the patient reported the same episode in different areas of the gingiva, always subsequent to the scaling and root planing therapy. This case is similar to the one of the present article; in fact, both cases had multiple erythematous lesions with ulcerated surface after local trauma (the periodontal interventions). Similarly, the histopathological study in Curran and Rives’ case9 shows ulcerated tissue with inflammatory infiltrate, in which lymphocytes were the most abundant cells, and the systemic health condition determines the ABH diagnosis in both case reports.

CONCLUSION

ABH could be diagnosed in this case despite the fact that it occurred in the vestibular area of upper teeth following a crown enlargement surgery-a condition that is unusual and has not been reported in the revised bibliography-. This highlights the importance of conducting follow ups after each surgical procedure.

text in

text in