INTRODUCTION

The schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, neurinoma, or perineural fibroblastoma, is a slowgrowing benign neoplasm of the peripheral nerves usually located in soft tissues;1 it is composed of Schwann cells, which is a type of glial cell surrounding the axon of the neurons and forming the myelin sheath, mainly in charge of correctly guide the axon growth.2 The schwannoma was first described in 1910.3 In most cases, the tumor starts between the ages of 20 and 60 years;4 the global incidence rate is 1 to 20 cases per 1,000,000 inhabitants per year.4 About 25 to 48% of all cases affect the region of the head and neck; in the oral cavity, it is mainly seen in the tongue, the buccal mucosa, and the lips.5

Its pathology is characterized by solid, subcutaneous, asymptomatic lesions;6 histologically it is composed of prototypes of cell organization called Antoni A and Antoni B.2 The Antoni A region is a hypercellular zone whose cells are fusiform with nuclei arranged in palisade forming parallel rows and producing the Verocay bodies. TheAntoni B region is a hypocellular zone characterized by predominance of a loose myxoid stroma with degenerative changes, such as formation of cysts, calcifications, hemorrhages, hyalinization, and inflammatory infiltrate.8 It is not frequent for these degenerative changes to become malignant sarcomas,9 which are invasive and have metastatic potential;9 if they occur, may be associated with incomplete resection of the lesion.2

Once the surgical excision of the lesion has been completed, the diagnosis takes place when the histopathological study is carried out.4 Similarly, a CT scan or a magnetic resonance image can show the extent of the lesion.10 The immunohistochemical tests show that the schwannoma cells are positive for protein S-100.3 Other cellular markers associated with neuronal tumors are: E.N.E., vimentin, glycoprotein, SMA, desmin, and dimentin (leu-7).11,12 In addition, the ki-67 protein as a marker allows determining cell proliferation.13

Generally, the prognosis of this lesion is good; its malignant transformation has been reported in very few occasions.10 Treatment consists of complete resection of the lesion while preserving the function of the involved nerve.14 If malignancy is confirmed (which is very rare),9 extended resection and chemotherapy is recommended.14

This report presents a clinical case of schwannoma located on the bottom of the right vestibular area of the oral mucosa, with diagnosis histopathologically confirmed, in a patient seen for routine dental consultation at Institución Universitaria Colegios de Colombia (UNICOC) clinic at Cali.

CASE PRESENTATION

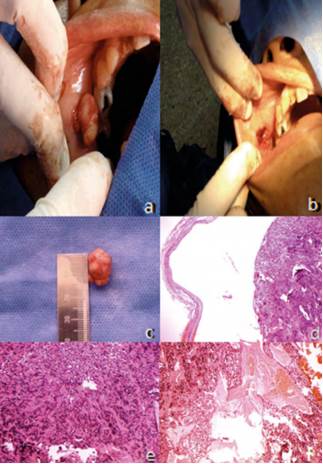

A 55-year-old Caucasian female patient attending a routine dental appointment at the UNICOC clinic. During the clinical evaluation, the right oral mucosa area showed a sessile, nodular, circumscribed mass invading the submucosa, covered by a normal movable mucosa; the mass was asymptomatic to palpation, measuring approximately 2 cm in diameter Figure 1A, 1B and 1C). The patient referred presence of the lesion about 1 year ago, with slow and painless growth. There is no evidence of alteration in tissue permeability nor paresthesia. Based on the clinical characteristics, the presumptive diagnosis was a fibroma.

Figure 1 A) image of the tumor lesion in the submucosal area of the right vestibular area behind the cheek, extirpated through surgical dissection. The encapsulated mass protrudes during surgery. B) image of the surgical niche of the lesion. C) image of the encapsulating mass in mm. microscopic view of the schwannoma tissue at 4x, showing the fibers of the encapsulation band. E) microscopic view of the schwannoma tissue at 10x under hematoxylin and eosin staining; the Verocay bodies can be seen. F) microscopic view of the schwannoma tissue at 10x under hematoxylin and eosin staining; the bleeding process within the mass of the tumor can be seen.

The extracted mass allowed cleavage planes for its total dissection; it was fixed in 10% formalin; the histopathologic and immunohistochemical study was later performed.

Macroscopic examination

The macroscopic examination showed a firm, elastic tissue of internal fibrous appearance, from the right vestibular submucosa area behind the cheek. The sample was nodular-shaped, measuring 1.8 cm in its widest point. For procedural purposes, it was cut into two halves and sent to the laboratory Figure 1C).

Microscopic examination

The sections of the specimen showed a neoplasm tightly encapsulated by a fibrous band Figure 1D) fully covering the hyperplastic component, which is derived from the Schwann cells of peripheral nerves. The histological expression of the tumor corresponds to a firm nodule of spindle-shaped cells with pyknotic nuclei arranged in bands that build longitudinal fibrils; the ones that are transversally cut are arranged in palisade with a fibrillar hyalinizedcore forming Verocay bodies Figure 1E). The inner part of the tumor shows dilated and congestive vessels; other sites show pseudocyst cavities with pools of amorphous content Figure 1F). The edges of tumor resection are entirely surrounded by the fibrous band that encapsulates it. There is no evidence of malignancy.

Immunohistochemical tests

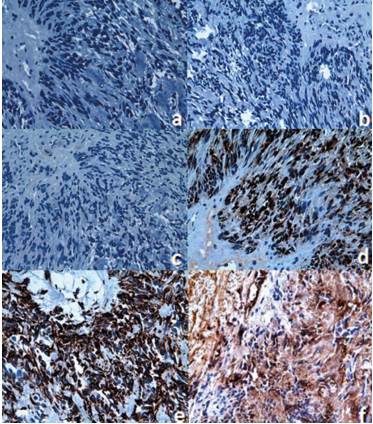

To confirm that the neoplasm derives from Schwann cells, the following markers were evaluated: neurofilament Table 1 and figure 2A), glial fibrillary acidic protein Table 1 and figure 2B), synaptophysin Table 1 and figure 2C), Leu-7 Table 1 and figure 2D), protein S-100 Table 1 and figure 2E), dimentin Table 1 and figure 2F).

Table 1 Guidelines for the diagnostic differentiation of schwannoma (modified from Buric et al12)

| Markers | Result |

|---|---|

| Encapsulation | + |

| Pathological formation | Antoni A and Antoni B areas with Verocay bodies |

| Cell differentiation | High |

| Source of internal bleeding | + |

| Tumor necrosis | - |

| Protein S-100 | + |

| Leu-7 | + |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) | - |

| Synaptophysin | - |

| Neurofilament | - |

| Vimentin | + |

Figure 2 Microscopic view of the schwannoma tissue at 40x. A) Negative immunohistochemical staining for the neurofilament. B) Negative immunohistochemical staining for the glial fibrillary acidic protein. C) Negative immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin. D) Negative immunohistochemical staining for Leu-7. E) Positive immunohistochemical staining for S-100 protein. F) Positive immunohistochemical staining vimentin.

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas are rare benign neoplastic lesions.15 In 2006, in 44,000 samples sent to the Pathology Unit of the University of Sheffield School of Dentistry (United Kingdom), a study was conducted to determine the range of histopathological lesions diagnosed in patients over 17 years of age for a period of 30 years (1973-2002), finding out that of the 2.452 cases of benign tumors, 43 were schwannomas, i.e. only 1.8% of prevalence.16

In Brazil, a study was conducted in 2011 to describe the clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical profiles of schwannomas and neurofibromas in 9,000 cases of oral lesions during a period of 38 years (1970 to 2008); only 4 schwannomas were found, accounting for 0.17% prevalence. In addition, there was predilection for males (3:1), an average age of 34.7 years, and a size of 2.8 cm in average.3 In the present report, the tumor lesion measured 1.8 cm in a 55-year-old woman.

Generally, the prevalence of schwannomas is 25- 50% in the area of the face and neck; in terms of the intraoral location (1-12%),7 they are mostly seen in the tongue and the floor of the mouth,17 followed by the area of the buccal mucosa and the lips.7 The schwannomas in lips are considered uncommon.18 The present case of an intraoral schwannoma was located on the buccal mucosa, which is also an uncommon location.14

The exact location of the nerve originating the lesion may be impossible to establish, and is identified in only 50% of cases.17 In our case, the exact location was not identified, but the presumed source can be the peripheral branches of the facial nerve. A retrospective study conducted in nine cases of schwannoma of the oral cavity treated in the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Service (Spain), reported the submandibular and jugular-digastric location, where the tumor was dependent on the lingual nerve and the spinal nerve, respectively. 18

The schwannoma in our case was detected in the right oral submucous area, as a nodular sessile, circumscribed lesion covered by normal movable mucosa, with no evidence of alteration in tissue permeability; the lesion was asymptomatic on palpation, measuring approximately 2 cm in diameter.

The histological findings of this study are consistent with reports in the literature regarding the presence of Antoni A and Antoni B formations.15,16,19 Generally, the presumptive clinical diagnosis can refer to benign tumor lesions like fibroma, lipoma, or tumor of salivary glands.10

The immunohistochemical tests show that the schwannoma cells are positive for S-100 protein Figure 2E) and vimentin Figure 2F), which is associated with the benign tumor of peripheral nerve.3,20 The S-100 protein normally appears in cells derived from the neural crest (Schwann cells, melanocytes, and glial cells).21 Several members of the S-100 protein family are useful as markers for certain tumors and for epidermal differentiation. They can be found in melanomas,22 in 50% of malignant tumors of peripheral nerves in schwannomas, as well as in cells of stromal paraganglioma, histiocytoma, and clear cell sarcomas. In addition, the S-100 proteins are markers for inflammatory diseases and can mediate inflammation and act as antimicrobial agents.23

Another used marker that was positive is vimentin Figure 2F). This marker is often used to identify mesenchymal cells. It is also commonly found in metastatic progressions.24 It is reported that when vimentin is negative, angioleiomyomas can be discarded.12,25

As to Leu-7, it showed a positive expression Figure 2D). This protein is an antigenic marker of lymphocytes, specific for natural killer cells, which is expressed in benign and malignant nerve sheath tumors, as well as in neuroendocrine tumors.26,27 The expression of Leu-7 has been reported in a differential manner for schwannoma25 Table 1.

The glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was negative in the reported case Figure 2B). This is one of the fibrous proteins that form the intermediate filaments of the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly glial cells such as the astrocytes.28 The neurofilament marker Figure 2A), which is used to differentiate other types of neural tumors of neural, like the neuroma, was also negative.29

Finally, synaptophysin was also used Figure 2C). This protein is found in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons and in neuroendocrine cells, and therefore is a useful marker to identify neural and neuroendocrine neoplasms and carcinoid tumors.30 This marker was not expressed, suggesting that there are no problems in neurotransmission from the involved tissues.

The presence of cystic formations, calcifications, hyalinization, and hemorrhage is a sign of degenerative changes that are not determinants of malignancy.17 Congestive and dilated vessels were identified inside the tumor. Pseudocyst cavities with pools of amorphous content were observed in other sites Figure 1D).

The prognosis of schwannomas is generally favorable, provided that the lesion is completely removed, maintaining a conservative approach;18 however, occasionally there may be local aggressiveness and up to 2% of malignancy, identified by the presence of distant metastasis.13 The patient in this study went through several clinical exams, which did not show neurological deficit, pain or alterations in mucosa permeability. Other reports, in which neurologic compromise is obvious, used a particular surgical intervention. For example, in Finland, a case review was conducted to evaluate spinal cord neurilemomas in 20 patients who had partial surgical excision of the tumor to avoid damages in the nerve; in that case, there was local post-operative pain (46%), as well as radiated pain (43%), and paraparesis (31%).31

text in

text in