INTRODUCTION

Forensic dentistry solves problems that go beyond the identification of human bodies postmortem. Globalization has brought along the problems of a changing society due to the current mobility of population around the world, creating new challenges for the profession.(1) Various reasons, such as adoption processes, participation of athletes in sporting events, the provision of state benefits, immigration, criminal proceedings, and verification of age for retirement purposes, require the estimation of the chronological age of individuals.(2,3,4)

The development of identification methods has gone through several stages, from the visual and radiographic interpretation to the use of technological aids, with physical, biochemical, molecular, and genetic analyses in constant innovation.(5,6,7)

The first records of the role of forensic dentistry in determining the chronological age of individuals traces back to 20th century England during the industrial revolution.(8) Long working hours and precarious social conditions affected adults and children alike. State regulations established the number of weekly working hours according to age groups and banned the work of children under 9. A large portion of the population lacked birth certificates, or these were incomplete, so age determination was done using subjective methods such as the person’s height. In 1937, Dr. Edwin Saunders defined a table of age recognition according to the clinical visualization of the chronology of tooth eruption; this had a great social impact and marked the beginning of scientific evidence-based forensic dentistry.

Many authors continued this research field focusing on the clinical and radiographic study of the chronology of tooth eruption, such as Demirjian et al (1973),(9) Solheim (1993),(10) Kvaal et al (1995),(11) and Kvaal and Solheim (1994),(12) who created identification methods to determine the age of children and young adults. For the determination of age in adulthood, researchers had to avail themselves of the physiological changes that occur with aging only. In 1950, Gustafson(13) determined the post-eruptive dental characteristics, relating them to the age of the studied population. Based on this approach, various authors have combined and refined the study of these features, improving the validity of the obtained measurements. Using cutting-edge technology, new biochemical studies have been added, such as racemization of aspartic acid, carbon 14 detection, and tooth fluorescence. All this confirms that this is a field in constant development.

The objective of this review is to analyze the various dental methods used to determine the chronological age of living or dead individuals, as well as the advantages and limitations of these methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A search in the Sistema de Bibliotecas de la Universidad Mayor (SIBUM) was conducted, including Dentistry & Oral Sciences Source, ClinicalKey, and Science Direct Freedom Collection, and selecting articles published between 1980 and 2014. A manual search was also conducted, including journals and texts on the topic, this time with no limitation in terms of year of publication. The inclusion criteria were research studies aimed at determining the chronological age of individuals by forensic analysis of oral tissues. All articles published in a language other than English were excluded, reaching a final sample of 70 items to analyze.

Methods for age determination

Different age groups indicate different forensic dentistry methods to determine the chronological age of individuals. Thus, there is a group of individuals from 0 to 13 years-a period that ends with the eruption of the second upper permanent molars-and another group of individuals aged 14 to 21 years, that goes from full crown formation of third molars until full eruption.(13) In older ages, the changes observed in teeth are mainly associated with physiological aging. Measurements in this age group are more complex as individuals are more vulnerable to modifications by the influence of environmental factors or by the individuals’ habits.

1. Individuals aged 0 to 13 years

This age group presents the best accuracy in determining chronological age, based on the abundant information provided by the chronology of tooth formation and eruption, as well as the easy access to clinical inspection and x-rays. Various researchers, including Kvaal et al(12) together and separately, have searched information for this age group. Researchers today are still using their methods in populations of different ethnic groups to validate the achieved results.(14)

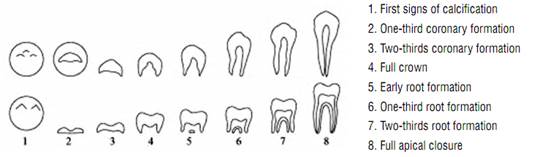

There are visual methods available, corresponding to the clinical observation of tooth eruption, which are influenced by the examiner’s skills and the low frequency of obstacles, such as crowding, lack of space, cysts, and tumors, which limit tooth eruption. The most commonly used measurement is currently the comparison or analysis of panoramic dental x-rays. A variety of identification methods have been described, including those by Demirjian et al,(9) Kvaal et al,(11) Nicodemo, Morais and Médici Filho,(15) which compare the degree of development or dental calcification using numerical tables or illustrations (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Figure 1 Original diagram “State of development of permanent dentition”, created by Demirjian, Goldstein and Tanner(9)

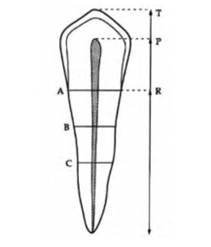

Figure 2 Diagram showing the measurements performed to determine the age of individuals. T: maximum tooth length; R: root length by mesial surface; P: maximum pulp length; A: root and pulp width in the cementoenamel junction; B: root and pulp width between measures of levels A and C; C: root and pulp width between the apex and the cementoenamel junction. Kvaal et al (11)

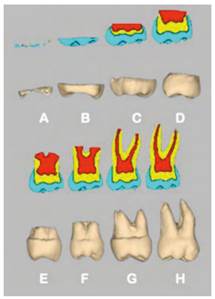

Figure 3 States of teeth mineralization based on mineralization chronology, proposed by Nicodemo, Moraes and Medici(15)

These analyses provide information on the chronological age and degree of maturation of individuals, according to the associated percentiles. In addition, these results can be compared and complemented with information from medical x-rays of carpal bone, phalanges and vertebrae calcification.(16) Most scientific information available is based on Caucasian populations, while the literature onAfrican,Asian or indigenous populations is scarce. There are differences according to medical history, racial group, socioeconomic level, and gender, since men have a slower development. Current research is focused on increasing the amount of information on the various racial groups.(14,15)

2. Individuals aged 14 to 21 years

Most countries define legal adulthood between the ages of 18 and 21 years, an age associated with legal independence and legal penalty, so it is critical to define this age in the case of individuals who lack a birth certificate or whose documents have been altered. The method most commonly described in the literature for this age group is the evaluation of the development or calcification of third molars by means of intraor extra-oral radiographs.(2)

Most studies find that age estimation is not very accurate. A determining factor is connected to alterations in measurements due to operator skill and patient cooperation during intraoral radiographs. There are also differences in terms of maxillary, ethnicity, presence of diseases, anatomical obstructions, and environmental factors. Schmeling et al(3) recommend using also the assessment of hand, wrist, and collarbone, in conjunction with the analysis of third molars. Cameriere et al(17) combine the radiographic evaluation of development of third molars with the assessment of the pulp chamber/ crown area ratio.

A study developed by Mincer et al in 1993,(18) endorsed by the American Board of Forensic Odontology, determined that if third molars have complete root formation, the probability for individuals to be 18 years or older is 90.1% in men and 92.2% in women from Caucasian origin.

Figure 4 Classification of third molars using the mineralization model by Demirjian et al, adapted by Mincer et al(18)

3. Individuals over 21 years of age

This age group presents the greatest challenge to forensic dentists, since the difference in chronological age can only be seen by dental changes and periodontal tissues associated with physiological aging. There is high variability among individuals in terms of nutritional status, occupation, the presence of trauma, caries, or periodontal disease, and drugs and alcohol abuse, to name just a few reasons.

In 1950, Gustafson(13) published a technique to estimate age in adults. This statistical method combined six independent parameters of progressive changes: degree of occlusal attrition, root transparency, secondary dentine apposition, gingival recession, number of layers of root cementum apposition, and degree of root resorption. They were classified into four stages (with a score of 0 to 3), considering that each parameter progresses at the same pace with age. Each stage was just as effective individually evaluated, and each was given the same level of importance. Gustafson’s method showed an error rate of 7 to 8 years, including 95% of the population. This method has not been successfully replicated with the same results by other authors.(19)

So far, researchers have limited themselves to the study of two to three characteristics simultaneously, such as root transparency and cementum apposition. Relying on the available technological advancements, such as electron microscopy and computed microtomography, they have been able to improve the validity of the results. They have also used linear regression formulas, which have allowed improvements to the methodology. The following are some of these methods.

1. Anatomical methods

a). Degree of external root resorption

According to Gustafson,(13) of all the parameters associated with age, external root resorption is the least reliable. The preferred method for viewing it is intraand extra-oral x-rays.

b). Degree of occlusal attrition

Occlusal attrition is strongly influenced by cultural and dietary habits. In 1984, Smith and Knight(20) created a rate of tooth wear as an epidemiological tool (Tooth Wear Index, TWI). This method is mainly used to determine the cultural and dietary habits of populations, with anthropological purposes.

2. Histological methods

a) Secondary dentin apposition

Progressive dentin apposition reduces the pulp chamber in size, modifying the dimensions and the relationship between the size of the pulp and the size of the crown. The assessment is done through the analysis of histological sections or using intraoral radiographs. The advantage of the radiographic analysis is that it is not invasive or destructive; in addition, it is inexpensive, can be performed ante or post-mortem, and the technique is widespread among practitioners. In 1995, Kvaal et al(11) designed a non-invasive, easy to use radiographic analysis method based on dental morphology. In the statistical tests they conducted an analysis of regression, leaving age as a dependent variable, finding out a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05). Some variations have been made to this method using computed microtomography, achieving greater accuracy in the results. (17)

b). Number of layers of cementum apposition

The thickness of the cementum increases with age by apposition, becoming thinner at the cementoenamel junction and thicker at the root apical third. The histological evaluation of this parameter requires extractions and root section, being a destructive and costly method. Solheim(10) and other researchers have reported a connection between cement thickness and age. However, this connection is inaccurate because it is strongly influenced by dysfunctional habits or history of periodontal disease. Using microscopy, it is also possible to measure the number of incremental lines of apposition of the cement in the form of dark and light bands; this type of study was initially developed in the field of animal biology. In 1992, Stott et al(21) observed the presence of incremental lines in humans, but these show high variability because the cementum is not deposited uniformly in humans; there is variation among the different teeth and between sections of the same sample. There are also very thin lines which can be difficult to read, as well as variations in the apposition cycles. In 2004, Wittwer-Backofen et al(22) incorporated more modern and elaborate techniques using electron microscopy. They found an error of 2.5 years in the estimated age, with a 95% confidence interval, which makes this method more accurate than others. However, this was achieved by omitting approximately 16% of the samples because they showed patterns that were hard to read.

c). Root transparency

Root transparency is caused by sclerosis of the dentin tubules, causing resemblances of the index of refraction between the organic and the non-organic component. This process takes place at the apical one-third first and then moves towards coronal. Some changes can be seen on the crown, but these can be altered by the presence of caries, restorations, or attrition. There is no consensus about the etiology of these changes but they are associated with the presence of toxins from periodontal pathogens, absence of functional stimuli, and dietary and parafunctional habits. In 1991, Drusini et al(23) reported low Pearson correlation coefficient (0.84) between transparent dentin and chronological age. This is an invasive method that requires extraction, sectioning, and root polishing to analyze samples.

3. Biochemical studies

a). Amino acid racemization

The racemization of amino acids is the process of conversion of amino acids from the levorotatory to a dextrorotatory form-trying to maintain homeostasis-, a process that goes on even after death. The levorotatory form is the most active biologically, while the dextrorotatory form is inactive or potentially pathogenic. For these analyses, the L-aspartic acid of collagen dentin is preferred due to the good conservation post mortem and to a relative high rate of racemization. The racemization in dentin is affected by the anatomical location of the sample due to temperature and to the difference in chronological formation of crown and root; the different sides of the teeth have different levels of racemization.(8) To reduce these variables, some authors have developed a standardized technique, taking samples at predetermined locations and on certain teeth, and storing them in places with control of environmental factors. Waite et al(24) defined this as a simple and highly cost-effective technique. The chronological standard error is +/-3 years.

b). Absorption of carbon 14 in enamel

Global levels of carbon 14 increased due to the nuclear tests carried out on the ground during the years 1955-1963. This carbon was absorbed as carbon dioxide by plants and then ingested by animals and humans. In the year 2005, Spalding et al(25) reported the possibility of determining the date of birth independently from the date of death, with an average error rate of +/-1.6 years. Carbon 14 levels have declined over the years and therefore the results have varied, but at the same time the technology has improved, and now the tests are more reliable.

c). Dental fluorescence

Dental fluorescence is the latest method for the practical application of forensic dentistry. It states that the physiological and pathological changes suffered by dental tissues during a person’s life are reflected in different levels of fluorescence. Over the years, the enamel becomes more mineralized, smooth and thin, increasing in translucency. The dentin becomes less permeable by the increase of peritubular dentine and mineralization. In 2013, through a photographic colorimetric analysis, Da Silva et al(5) assessed fluorescence in intact upper central incisors of individuals of different age groups. They concluded that fluorescence is stable between the ages of 7 and 20 years, reaching its highest values at the age of 26.5 years, and then decreasing over the years; these values are statistically significant. This contrasts with the study by Matsumoto et al in 1999,(7) who by means of an in vitro analysis of fluorescence with a microphotometer concluded that fluorescence increases with age. In addition, they claim that this phenomenon is directly dependent on temperature, meaning that the higher the temperature (50° C) the higher the fluorescence. They also discovered that the values can increase over time, even on extracted teeth. This discrepancy validates the need for further studies on this method to solve the current controversy.

Because of the renewed interest in the determination of the chronological age as a practical application of forensic dentistry, further studies are needed to provide better and more standardized information and to offer scientific evidence for different populations, in order to define the age of individuals more accurately, and thus meet the needs of current multicultural populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Most methods included in this study involve some degree of invasion to the subject under study- from irradiation to obtain a radiographic image to tooth extraction to conduct biochemical tests-. In addition, none of these techniques is accurate on its own, so it is recommended to combine different measurement techniques, opening the doors to a field of research for less invasive techniques as a complement to the existing ones. Finally, the available information suggest that research on populations of African and Asian origin is lacking, representing a new challenge due to globalization, migrations, and the heterogeneity of current populations.

text in

text in