Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Investigación y Desarrollo

Print version ISSN 0121-3261On-line version ISSN 2011-7574

Investig. desarro. vol.16 no.1 Barranquilla Jan./June 2008

THE END OF THE VIENNESE WAY?

CHANGING STRATEGIES AND SPATIAL IMPACTS OF SOFT URBAN RENEWAL IN THE AUSTRIAN CAPITAL

MICHAELA PAAL

DR., PROFESORA TITULAR DE LA FACULTAD DE GEOGRAFÍA, UNIVERSIDAD PHILIPPS DE MARBURG (ALEMANIA)

CORRESPONDENCIA: FACULTAD DE GEOGRAFÍA, UNIVERSIDAD PHILIPPS DE MARBURG DEUTSCHHAUSSTRASSE 10 D35037 MARBURG (ALEMANIA)

paal@staff.uni-marburg.de

FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: MARZO 6 DE 2008

FECHA DE ACEPTACIÓN: MARZO 27 DE 2008

ABSTRACT

Since the late 1970s the Austrian capital Vienna is one of the most exciting European examples for successful and well-balanced urban renewal policy. The strategies to safeguard historical building fabric are mainly influenced by a welfare state urban development policy.

During the last three decades urban renewal activities, mainly funded and/or supported by public aid and distributed all over the urban space, kept the urban development in balance and avoided occurring social segregation as well as the growth of slums.

In the meantime, neo-liberalistic globalization as well as the chance to get financial support for large-scale urban projects form the European Union generate some renunciation from this successful strategy. As the Viennese municipality more and more turns towards prestigious projects to enhance international location competitiveness, the cycle of urban decay in the former renewed quarters might start again.

KEY WORDS: They urban renewal policy, urban development policy, spatial impacts.

RESUMEN

Desde el final de los años 1970s Viena la capital austríaca es uno de los más interesantes ejemplos de política de renovación urbana, la cual fue implementada básicamente con un plan regulador estatal y principalmente orientada a grandes edificios de fábricas. Durante las últimas tres décadas la actividad de renovación urbana se fundamentó en el sector público y se distribuyó por toda el área de la ciudad manteniendo un balance en el desarrollo urbano impidiendo una fuerte segregación social así como la generación de "Slums". En la actualidad, bajo el concepto de la globalización visto como un recurso importante para la generación de proyectos de gran escala a nivel europeo, se presenta una renuncia de la estrategia anterior, construyéndose proyectos prestigiosos para mantener la competitivi-dad internacional mientras que comienzan a aparecer síntomas de decaimiento urbano muy fuertes.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Política de renovación urbana, política de desarrollo urbano, impacto espacial.

1. INTRODUCCIÓN

In the early 1970s in most of the European capitals a strong period of urban extension and suburbanisation came to its end. Young and wealthy people began to re-discover the historical centres, started with renovation of residential flats and supported the complete change of the Inner city real estate market. As it had started in the "Marais, one of the most famous quarters in the historical centre of the French capital Paris, in the late 1960s, this renovation was mainly financed and executed by private investors (Bastie, 1980). Therefore the displacement of former inhabitants, caused by the constructional and social valorisation, gained in importance.

In the case of Vienna, the situation was a little bit different from other European countries. First of all, in the marginalized site of the city nearby the Iron Curtain, neither in economics nor in real estate market dynamics the process of reurbanisation could be watched. It did not take place. The Austrian capital's population was shrinking since the end of the Second World War from more than 2 million (1938) to 1,5 million in 1981.

According to this background, it was the municipality itself, who decided to re-invest in the historical centre. In relation with the long-term socialist urban planning policy, they were looking for strategies to avoid all negative consecuences of urban renewal such as gentrification, exploding prices on the real estate market and speculation. The combination of subject and object funding, financed by the municipality, was born.

During twenty-five years this "Viennese way", often copied by other countries, had been one of the most successful strategies in Europe. But in the meantime geopolitical changes are causing the turning away of soft urban renewal. The necessity of international location competition leads towards large-scale urban projects and seems to stop the former cycle of urban renewal.

2. THEORETICAL APPROACH: THE CYCLE OF URBAN DECAY AND URBAN RENEWAL

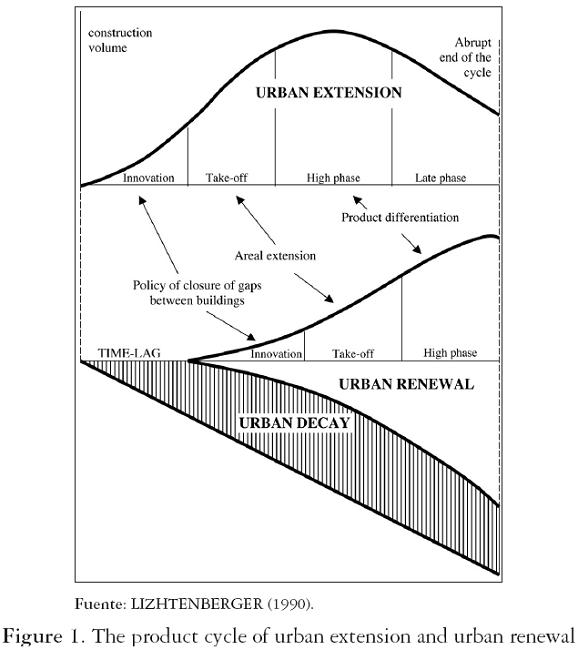

The periodical change of urban extension and urban renewal might be interpreted against the background of theory of evolution (Lichtenberger, 1990). The product cycle theory has been developed by biologists and later has been transformed and integrated in economic sciences. It deals with the implementation, growth and decline of products or phenomena. Within urban geography, the product cycle theory nowadays is mainly used to explain the consequences of specialization in services (Cattan et al., 1994; Paal, 2005) but it was first implemented in urban research for interpreting consecutiveness of urban extension and re-urbanisation (Lichtenberger, 1990).

The following explanations focus on Western European urban development, due to the fact, that even within Europe processes of urban growth and decline are quite different and have always been caused by different political systems.

Urban extension and re-urbanisation never start at the same time. The most important periods of extension of the urban building area in Europe were caused during industrialisation, mainly in the second half of the 19th century, and in the reconstruction of residential flats and the suburbanisation and in the 1950s and 1960s (figure 1 - phase of innovation). Especially after the end of the Second World War urban planners tried to repair damages and to satisfy the demand of residential buildings by closing the gaps between buildings within the densely constructed area. In relation with the economic growth and increasing welfare, even of the middle class, suburbanisation and the construction of one-family-houses takes place and means urban growth towards the suburban municipalities (Take-off, mainly as extension of peripheral settlement areas).

The core city loses importance as residential location and even as the main economic centre and it is mainly dominated by elder people, single households and lower social classes, to whom migration towards the green suburban areas is too expensive. Residential blight and commercial blight lead to lacking of reinvestment in the historical constructed area and cause urban decay (time-lag which causes urban decay). The dimension of decline corresponds to the structure of the constructed area. Generally industrial buildings are faster concerned by urban decay than residential buildings (Lichtenberger, Csefalvay & Paal, 1994).

The product cycle of urban extension as well as of urban renewal might be divided into four phases. Innovation means the early implementation of the cycle with experimental application of new methods/planning strategies. During the take-off these strategies become standardized and are applied all over the urban area during the High phase. In the late phase the cycle is executed and interrupted abruptly (Lichtenberger, 1990).

The end of the urban extension cycle is reached in the early 1970s. A small group of trendsetters starts to re-discover the historical centre as well as the surrounding inner districts (innovation in urban renewal). They are looking for urban entertainment, urban infrastructure, the proximity to cultural events and apartments with "urban flair". Their re-investment in historical building (19th century and older, residential as well as vacant industrial buildings) brings back speculators to the inner districts, who try to benefit from the new trend. As the real estate market for newly renovated flats increases, gentrification takes place and dramatically changes the socio-economic structure of the renewed districts (take-off and high phase of urban renewal).

Like the period of urban extension, urban renewal might be also interrupted by changes of political and economic conditions, too. One of these breakings has been the Fall of the Iron Curtain which transformed not only Eastern metropolises but also concerned former peripheral cities, which got afterwards a new, central role within the European urban system, as Vienna did.

3. IDENTIFICATION OF DEMANDS ON URBAN RENEWAL -THE VIENNESE URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND THE HERITAGE OF THE 19TH CENTURY

To understand the specific needs on urban renewal in Vienna, it is necessary to have a look at its urban development. As most of the European metropolises, Vienna had been imperial residence during centuries, but had its most important period of urban growth during the second half of the 19th century. The industrialisation supported the creation of a broad belt of industrial enterprises and flats for the working poor in the outskirts of the medieval city. At the same time the fortification was demolished to enhance the extension of the constructed area and to create new space for representative buildings, financed by the government (the monarchy) itself as well as by the nouveau-riches industrialists.

In contrast to other European capitals, the old town of Vienna has never been concerned by urban decay. The state and the municipality always tried to protect the official buildings, which dominate the historical centre. Outside from the representative boulevard, called "Ring", which surrounds the historical centre, the situation was dramatic. The residential flats, especially in the belt of the 19th century extension needed urgent investment. Due to political reasons, the rents had been frozen by the time of the First World War. Therefore and in relation to the demand on floor space, re-investment by the private owners did not seem to be attractive. The quarters with their small flats without toilets or bathrooms inside, often with only one water intake point at the corridor, became attractive for immigrants from the South Eastern European countries who had -as they had not the Austrian nationality- no right to ask for low cost housing.

After the Second World War -far away from any pressure on real estate market- the municipality enforced urban extension. Its main goal -and inspired by the socialist tradition- was the amelioration of the quality of life for people living in the small and comfort-less flats of the 19th century. Especially in the North Eastern periphery large-scale residential settlements had been constructed, mainly low cost housing. Investment within the densely constructed area focused on the enclosure of vacant allotments, also mainly undertaken by the municipality.

4. STRATEGIES OF URBAN RENEWAL IN VIENNA

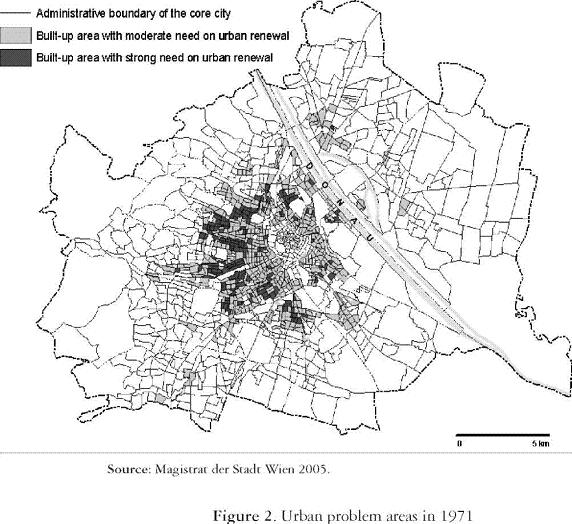

At the end of the 1960s the demand on new dwellings was supplied. Many owners and tenants kept their cheap apartments in the core city, left them vacant to ensure them for their heirs and settled in the suburban belt, at first as secondary residents, later on they stayed there permanently. The missing re-investment and the vacant dwellings disposed the municipality to enforced engagement concerning the 19th century-belt. The Department for Urban Planning started a structural analysis about the urban problem areas in 1971. As problem fields they defined age of the buildings, size of residential flats, defects in living comfort, density of population in the quarters as well as in the buildings. The results proved the former suppositions (figure 2).

The needs of intervention in urban renewal concerned almost the whole densely constructed area from the 19th century, especially the quarters of the working poor. But in contrast to other European cities, urban renewal in Vienna did not mean slum-clearing, appropriation of building land to satisfy increasing demand or serving specific interests of investors. Urban renewal in Vienna was strongly oriented to social welfare and low cost housing policy. The municipality understood urban renewal as a lot of small-scale interventions, located all over the municipal area. Hence it is amazing, that the Viennese urban planners did not follow their own principles in their first project. They decided to start their interventions in a small delimited area near the historical centre, a closed 16th century ensemble, the former Viennese red light district, the so-called "Spittelberg". The municipality bought more than 80 buildings to avoid speculation, installed a "zone for conservation of ancient buildings" and started renovation.

They decided against demolishment, as it had been practiced in France or even in Germany, and gutted only in three cases, where the buildings had been severely damaged. Compensation of dwellings was offered to the tenants. The intervention was financed by the municipality's "Fund for urban Renewal", supplied by taxes from Viennese house owners. After the end of the renovation which preserved the historical structure, the municipality sold the flats to private prospects. Unfortunately, it happened exactly the opposite if what the municipality had tried to avoid: the apartments were too expensive for the former inhabitants. Today the quarter is completely gentrified, and with its gastronomic offers it is one of the tourist attractions and centre of cultural events.

After this early experience with urban renewal and its consequences, the municipality modified the strategy. The principle "preference of preservation of the historical buildings against demolition" was furthermore the paradigm. The implementation changed from acquisition of buildings by the municipality to direct funding of owners and tenants. For these purposes the municipality founded in 1984 the so-called "Wiener Bodenbereitstellungs- und Stadterneuerungsfonds". This fund should prepare, execute and supervise all interventions in urban renewal and was funded by taxes. In contrast to the example of Spittelberg, the amelioration of residential flats and the renovation of buildings should not be concentrated on closed protection zones, but should concern all Viennese districts. The conservation of the old buildings under social considerations they called "soft urban renewal". During the whole duration of renewal the inhabitants stayed in their flats and participated in renovation. But soft urban renewal not only meant the renovation of the flats themselves, but also the building services, the claddings and the amelioration of the neighbourhood improvement.

During the urban extension of the 19th century, the private speculators tried to capitalize the building lots at its best. This meant that 80% of the ground floor had been covered. In the backsides of the residential buildings small enterprises often had their production facilities. To enhance the neighbourhood improvement, the relocation of these enterprises to the outskirts of the city started. But most of them decided to leave the core city entirely, because they got offers from the suburban communities concerning cheaper building land and reduction of taxes. As Austrian municipalities generate their income mainly by business taxes, the municipality of Vienna has lost a lot of money to the present for the benefit of suburbia due to their location policy during the 1980s.

The former small trade production facilities at the backyards were demolished, and instead small parks for leisure were installed. To create closed green areas, it was necessary to start with planning not only for single buildings, but for the whole building block. This strategy was called "block renovation" by Viennese urban Planners, because they treated every building as a single object, but made a development concept for the whole block. Especially in the belt of the working poor (orange-coloured zones in figure 2) this method to improve the quality of life was very successful.

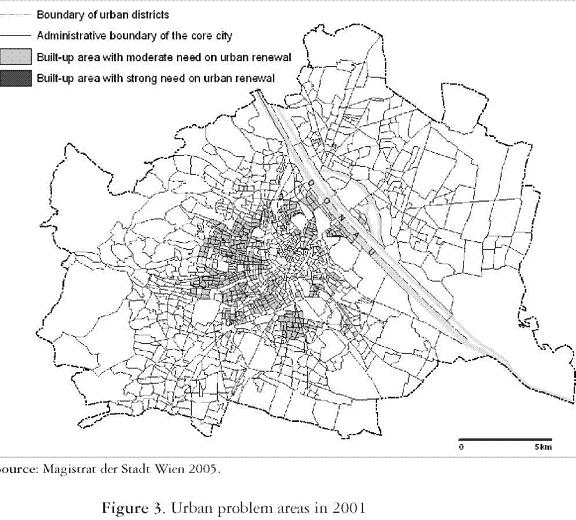

From 1984 to 2004 the fund supported the renovation of 4.335 buildings with more than 212.000 residential flats (Wiener Bodenbereitstellungs- und Stadterneuerungsfonds).

Approximately 4.000 million Euro have been invested, about 3.900 million Euro were financed by the municipality.

The success was impressive. Almost all zones with strong urban decay have been improved. Though even 2001 demands on urban renewal have been detected. And it also succeeded to avoid area-wide urban decay and to enhance the quality of life in the densely constructed area (Figure 3).

5. THE POLITICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHANGE: TURNING AWAY FROM SUCCESSFUL TREATMENT?

The European geopolitical change seems to break the cycle of urban renewal in Vienna. With the Fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Vienna regains its central role within the European urban system. International enterprises start looking for locations to conquer the Eastern European markets. In the early 1990s cities like Budapest, Prague or Moscow are involved in the period of transition from the plan to the market. This means enormous insecurity, especially in the context of transactions on the real estate market. Even infrastructure of communication is not as developed as in the Western countries. Therefore, the enterprises decide to install their branches abroad for Eastern European business in the Austrian capital.

Within a few years the demand on high-quality offices and apartments increases - the real estate market is booming. For the first time in the history of Viennese urban development the municipality allows private investors to construct skyscrapers even in the neighbourhood of the old town. In the meantime the boom is so strong that only the danger of losing the certificate "World Culture Heritage" protects the historical centre from more skyscrapers.

The municipality department for urban planning is extensively overstrained. After decades of "administration of the shrinking city" they are not able to give answer to the demands on new development. It is clear, that under these conditions, the traditional "soft urban renewal" is not in the focus of planning.

Beside globalisation, the Austrian integration in the European Union in 1995 has strong consequences for urban renewal, too. The European Commission does not support small-scale urban renovation. Their focus is only on large-scale urban projects in the framework of funding programs such as URBAN I and URBAN II. This means, that —if the city wants to benefit from the financial EU support- it has to change its development strategy.

This has happened in Vienna in the second half of the 1990s. The first project following EU guidelines is the re-vitalisation of a traffic infrastructure from the 19th century, which divides the inner from the outer districts. There, a railway which runs in the middle of one of the most important traffic lines of the city is installed on a brick construction The railway also divides the middle class districts from the outer districts, which are traditionally dominated by blue collar workers and immigrants.

The project "URBAN Intervention Gürtel West" identified an area of 626 hectares (this means 1.5% of the whole administrative area) as a problematic zone with high demand on urban intervention. More than 34% of the 132.000 inhabitants are immigrants, mainly from Turkey. 33% may be called "people with low income".

But instead of focussing in measurements in these districts, urban planners decided to restructure only the railway zone. They transformed the historical arches from craft locations to a new "scenario" for cultural events, hoping that private investors would undertake investment within the development zone nearby. In the meantime the revitalisation of the railway is finished, but the problems in the neighbourhood districts are still the same. This experience proves, that interventions in such "problematic" zones remain the responsibility of the municipality.

Other large-scale urban projects such as the modification of the former Imperial Mews into a museum quarter or the restructuring of former industrial buildings of the 19th century, three ancient gasholders, into apartments, offices, shopping mall and Cineplex centre provided international attention. To be "resounded throughout the land" is very important for cities which are interested in safeguarding their image as modern and innovative locations. It is not only Vienna which decided for large-scale urban projects. Barcelona and Valencia in Spain as well as Hamburg in Germany are excellent examples of this new strategy. Even shrinking cities in old industrial regions try to get international attention by engaging international well-known architects in their projects and urban planning.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the scope of product cycle of urban extension and urban renewal, every cycle ends abruptly in its late phase. As urban extension is displaced by urban renewal, the period of intense urban renovation is not compulsory displaced by a restart of urban expansion. Instead, urban renewal seems to run out for the benefit of urban densification. It has to be discussed if this up-to-the-minute trend has to be understood as a new period of urban extension or if it means a new form of urban development.

Due to the fact, that urban planners and politicians are interested in keeping enterprises as well as upper class inhabitants within the administrative boundaries of the core city, they start to activate their expansion land. As building land in the densely constructed area becomes more and more scarce, waste industrial sites from the 19th century gain importance. These areas are mainly located near the inner districts with excellent accessibility — a location advantage which investors are looking for nowadays. During the 1970s waste industrial areas had been barricades for urban development, in the meantime they are in the focus of master plans and investment strategies.

This means, that on the one hand traditional urban renewal of several buildings or building blocks is displaced in favour of revitalization, restructuring and new development of urban industrial waste within the densely constructed area. On the other hand, the alternative land use means urban extension, too. The waste areas are mainly transformed into impressive sites for large-scale urban projects, as the "Harbour City" in Hamburg (Germany), the "Ciudad de las Artes y de las Ciencias" in Valencia (Spain) or the "Science City Adlershof" in Berlin (Germany). The scale of this urban development does not longer correspond to the former structures, nor in use neither in construction dimensions.

For a strategy like "soft urban renewal" the turning to large-scale projects is fatal. Geopolitical change, internalisation and the focus on prestigious urban development contradict completely the welfare-state- and social philosophy about treatment of historical structures. Within the rat race of international location competition, a city has no chance: to drop out or to keep out. This means, that for Vienna the era of municipal-socialism in urban renewal seems to be over now. Perhaps soft urban renewal might be realized only in case of specific political and economic conditions. The location of the Austrian capital as the most Eastern location of the Western European political system as well as the demographic and economic stagnation helped to conserve the idea of urban renewal under social conditions. In the meantime external pressure and increasing competition -often discussed in relation with globalisation and neo-liberalism— even catch up Vienna.

REFERENCES

BASTIE, J. (1980). Paris und seine Umgebung. Stuttgart, Borntraeger, Geocolleg 9. [ Links ]

CATTAN, N. et al. (1994). Le Système des Villes Européennes. Paris: An-thropos. [ Links ]

KLOTZ, A. (2006). Wien Weltkulturerbe. Wien: Eigenverlag. [ Links ]

LICHTENBERGER, E. (1990). Stadtverfall und Stadterneuerung. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. [ Links ]

LICHTENBERGER, E., CSEFALVAY, Z. & M. PAAL (1994): Stadtverfall und Stadterneuerung in Budapest. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. [ Links ]

LICHTENBERGER, E. (2006). Europa im Prozess der Globalisierung Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft 148, 151169. [ Links ]

MAGISTRAT DER STADT WIEN (2000). Entwicklungsszenarien der Wiener City. Wien: Werkstattberichte 9. [ Links ]

MAGISTRAT DER STADT WIEN (2000). Vienna Urban Planning. Wien: Eigenverlag. [ Links ]

MAGISTRAT DER STADT WIEN (2005). Stadtentwicklungsplan Wien 2005. Wien: Eigenverlag. [ Links ]

PAAL, M. (2005). Metropolen im Wettbewerb. Tertiärisierung undDienstleistu ngsspezialisierung in europäischen Agglomerationen. Münster, LIT. 16 [ Links ]

WIENER BODENBEREITSTELLUNGS- UND STADTERNEUERUNGSFONDS (o.J.). Blocksanierung in Wien. Wien: Eigenverlag. [ Links ]