Introduction

How do we perceive photographs? Can a photograph ever be a memory? What can we learn about memory, and our relationship with memory, from photographs? I have been exploring philosophical ideas of memory and its relationship with the self through photography, and this paper sets out the lessons learnt during that process.

In the first section I examine our relationship with photographs. The culturally accepted analogy equating photographs with memories is contrasted with their experimentally observed functions. The actual roles photographic images play in relation to memory defines them not as ‘memories’ but as mnemonic tools. I then examine the role of memory in our perception of photographs by revisiting the work of Roland Barthes. By placing his documented experience in the context of contemporary theories, the potential contribution of memory to affective perception of photographs is revealed.

Typically, photographs are second-generation copies of visual scenes external to the camera, captured in a fraction of a second. However, other photographs can be created that do not require a camera and do their work over long time periods. These photographs do not record phenomena external to themselves, instead recording what they directly ‘perceive’. The second section explains how I developed a photographic process broadly analogous to physical human memory: the metamorphogram. The type of memory represented by metamorphograms is examined against existing definitions of procedural, semantic and episodic memories, showing most similarity to a composite of all episodic memories recorded during an individual’s lifetime.

In the final section, this photographic analogy is used to explore relationships between individual and cultural/collective/social memory. Inspired by a Japanese folk- tale, several works were created which implied a bi-directional relationship between memory and self: that individuals can alter culturally shared memories, and in return cultural memories can affect individuals at the level of their autobiographical self. This relationship is explored in more detail, revealing a distinct form of non-institutionalised, non-behavioural, socially shared memory. Not fitting any extant definition, it is proposed that this be entitled ‘sociobiographic memory’.

1. Our perception of photographs

‘We capture your memories forever’

‘We are that strange species that constructs artefacts intended to counter the natural flow of forgetting’ (William Gibson, 2012)1

The question ‘how do we perceive photographs?’ can be interpreted in two ways, depending on our definition of ‘perceive’. First, it may mean ‘what do we recognize or understand photographs to be?’ As a society as well as individuals, we blithely entrust the recording of important memories to cameras; or, more precisely, to photographs. We even call the most perfect, albeit apparently non-existent, version of memory - in which every detail is recalled with absolute clarity- “photographic memory”. A generalized acceptance exists within society that a photograph is somehow equivalent to a memory. This apparent equivalence has been promoted and exploited by camera manufacturers Eastman Kodak since the 1960s and 1970s onwards. One print advertisement copy includes the following;

Then and Now Good Memories Deserve Good Processing

What are memories made of? […] You live them all once. You live them again and again in pictures […]. And make your memories last.

As economist Theodore Levitt noted, “Kodak promises with unremitting emphasis the satisfactions of enduring remembrance, of memories clearly preserved. […] The product is thus remembrance, not film or pictures.”2 The messages are clear: memories are ‘captured’ in photographs; photographs extend the functional lifespan of memories. The arts writer John Berger concurred, suggesting that photographs may be a direct replacement for memory:

What served in the place of the photograph, before the camera’s invention? The expected answer is the engraving, the drawing, the painting. The more revealing answer might be: memory (Berger, 1980, p. 54).

In this he iterated Susan Sontag, who stated that photographs are “not so much an instrument of memory as an invention of it or a replacement” (Sontag, 1979, p. 178). And so, we entrust our fallible memories to cameras which “cannot lie”.

However, Kodak, Berger and Sontag are wrong; in fact, Sontag’s quote works better reversed, to infer that photographs are not a replacement of memory, but an instrument of it. Photographs are not analogous to memories, but to tools. Participants in studies of how we use photographs directly refer to them as memories: “It’s important for me that they’ll have [the picture collection] when they are grown up, so they will be able to leave home with a big box of memories” (Whittaker, Bergman & Clough, 2010, p. 34). However, when participants’ interactions with photographs are further interrogated, it is clear that they understand the functional purposes, whether memorial, communicative or aesthetic (Fawns, 2020, pp. 3, 6, 8 & 9), for which they use photographs. Fawns describes a multitude of ways in which photographs are used to support (autobiographical) memory construction, recall, association and distribution. Participants in Fawns’ studies understand that they use photographs as tools to aid recall, noting that selecting images to keep is “important potentially in the future and you want to make the right choices” (Fawns, 2020, p. 6). They show understanding of how photographs trigger memory: “The photograph becomes the focal point of the memory system that everything then extends out from” (Fawns, 2020, p. 3). Fawns sees photographs as part of a process, including taking, sorting, viewing and distributing images, which we use to support memory. The photographs themselves are merely one of the tools in this process, interacting with our memory, functioning as symbols to be interpreted (Rowlands, 2016, pp. 160-162).

Our reliance on photographs as mnemonic tools is a double-edged sword. Photographs have been shown to aid reactivation of memories, but may also induce bias in our memory (see St Jacques & Schacter, 2013, pp. 537-343; St Jacques, Montgomery & Schacter, 2015, pp. 876-887 for examples), or, albeit in somewhat contrived circumstances, create completely false memories (Garry & Gerrie, 2005, pp. 312-315). Photographs clearly function in multiple and complex ways with our memory, often in the context of other contemporary non-visual (e.g. textual, verbal, social) information (reviewed in Garry & Gerrie, 2005). The strength of their potential influence led to the suggestion that photographs supporting memories can validate a sense of self (Heersmink & McCarroll, 2019, pp. 98-101).

Decades of research have provided objective clarity in terms of the function of photographs. Despite this, the power and simplicity of the label ‘memory’ for driving engagement with images (as evidenced by Instagram Memories, Google Photo Memories, Facebook Memories… and the continuing use of ‘memories’ as a hook word by almost every major camera manufacturer) suggests photographs will remain commonly perceived as memories. After all, who would buy a camera that lets you capture “visual tools to aid your recall”?

Punctum power

We have seen that the generalized perception of photographs as memories is at odds with their actual function as mnemonic tools. Given this role in triggering recall, I now return to the question ‘how do we perceive photographs?’.

The primary definition of ‘perceive’ by the Oxford English Dictionary is ‘to take in or apprehend with the mind or senses’ (further: ‘to apprehend with the mind; to become aware or conscious of; to realize; to discern, observe’).3 In this section, I restate the question as ‘with what aspects of our mind or senses do we interpret photographs?’ To answer I focus on Roland Barthes’ observations in Camera Lucida (Barthes, 1980). Barthes became fascinated by photography and photographs, examining the viewer’s relationship with images. Barthes’ testimony will be re-evaluated in the light of more contemporary philosophical theories.

In Camera Lucida Barthes describes finding a box of photographs belonging to his beloved mother, who had recently died. In some he recognizes his mother and other family members, with little affective consequence despite his obvious grief. However, in the “Winter Garden photograph”, which shows his mother as a child, he finds something immediately and profoundly affective. He attests that this image has captured the essence of his mother, allowing him to ‘rediscover’ her. How has Barthes perceived this photograph, and not others of his mother, such that it affects him so deeply? The image is explicitly not an autobiographical memory: it shows his mother as a young girl, long before he was born. Indeed, Barthes knows that “what [he sees] is not a memory” (Barthes, 1980, p. 82) and that “The Photograph [is] never, in essence, a memory” (Barthes, 1980, p. 91). For him it is “reality in a past state”; confirmation that what he sees once existed and has “evidential force” (Barthes, 1980, p. 89).

Barthes found affective power in some photographs, and knows this power relates directly to the viewer. He says of the Winter Garden photograph, “[F]or you, it would be nothing but an indifferent picture” (Barthes, 1980, p. 73). What strikes Barthes about photographs with affective content is something he describes as an image’s “intensity”; the part of the image which “jumps out and pierces” the viewer, an aspect of visual content which he calls a “punctum” and which “is poignant to [him]” (Barthes, 1980, pp. 26-27). His perception of the punctum is crucial for the effect, and Barthes understands that its presence or absence is viewer-specific.

Perceiving the punctum

Above, I defined the question under examination as “with what aspects of our mind or senses do we interpret photographs?”. So far, we have Barthes viewing photographs, but only finding affective content in a fraction of them. This suggests that while perception of photographs includes input of visual information, other aspects of perception facilitate recognition of a viewer-specific punctum able to transform indifferent pictures into objects with the affective capacity.

What is this punctum? Baudrillard, another philosopher captivated by photography, said that in most photography “what Barthes calls the ‘punctum’, that absent point, that nothingness at the heart of the image which gives it its power, no longer exists”. Baudrillard appears to equate the punctum with a “void”: a complete absence of symbolism. He suggests that taking a photograph of a living human which contains a punctum may be “almost impossible” (Baudrillard, 1998, p. 93) as there can be no “absence”.

Barthes seems to say that the punctum is more obvious when Death is present in the image. In the Winter Garden photograph and other historical images he notes that the subject is at once alive / going to die / has died / dead, suggesting some necessary relation to time or, as Barthes melancholically phrases it, “death in the future” (Barthes, 1980, p. 94). However, by no means all the puncta he uses to illustrate this idea are people. The punctum may be an object, a stance, a house, a sheet, or the entirety of the image. A punctum has the “power of expansion”, which Barthes says is often metonymic. He sees one thing, and his mind fills with much, much more. From a picture of a blind gypsy he “recognize[s], with [his] whole body” his long-past travels in Eastern Europe (Barthes, 1980, p. 45). In a photograph of an unknown woman he realises the punctum is due to his associating her necklace with that of someone he once knew (Barthes, 1980, p. 53), and from there a whole trail of memories related to this object unfolds within him. This same associationist phenomenon of “expansion” is also noted by participants in recent studies (Fawns, 2020: see the first section for an example).

The power of the punctum thus emanates from the viewer. Barthes and I would not share puncta, we would each find our own. I propose that each punctum’s power is due to a second aspect of our perception of photographs; that we perceive photographs in the context of our memory. The consequence of this perception is some level of emotional affect.

Not all images contain a punctum; they show nothing which “pierces” our memory and induces affect. Many are “inert under [Barthes’] gaze” (Barthes, 1980, p. 27), others elicit semantic memories such as recognition of a particular form of clothing. Photographs may therefore act with a scale of affect, ranging from nothing at all, through factual recognition, and all levels of “punctum” affect up to a punch-in-the-gut emotive force. The viewer-specific power of a photograph arises from the association of something within the image with an aspect of the viewer’s memory.

In the Winter Garden photograph, Barthes’ perception of the punctum which provides the affect is clearly expressed. Barthes receives the visual stimulus of his mother as a child, sees her particular pose, the line of her face, and is filled with emotion. The image itself has no intrinsic power; I doubt you or I would be affected should we see it. Barthes’ memory has been triggered to engage with this photograph. Therefore, the viewer’s memory, in concert with visual stimuli, determines whether any personally relevant or affective content is perceived.

From Barthes’ account we see the scale of affect puncta may trigger. Only the Winter Garden photograph arouses the notable affective state he discusses, despite looking at other photographs of his mother from the same box, including one “in which she is hugging me, a child, against her, [and] I can awaken in myself the rumpled softness of her crepe de Chine and the perfume of her rice powder” (Barthes, 1980, p. 65). Degree of affect can thus distinguish one image from another, even when the representational content -in this case, Barthes’ mother- is very similar. The Winter Garden photograph may be set apart as particularly valued for its ability to conjure such strongly emotional memories. Or, we may say, for the ability of Barthes’ memory to facilitate perception of it in such an intensely affective manner.

Barthes’ response to the Winter Garden photograph is so strong we may consider it as an evocative object, one which “intentionally or unintentionally aids us in remembering our personal past” (Heersmink, 2020, p. 7). The intensity of Barthes feeling suggests a “love-at-first-sight” moment, a viscerally affective flood of connected memories triggered by the image. Barthes could be describing the moments during which the Winter Garden photograph is transformed, for him, from a mere image into what we might now label a particularly powerful evocative object.

Overall, Barthes’ testimony, together with more recent empirical observations, suggest that perception of photographs is a complex process in which visual stimuli interact with memory to facilitate perception of anything of relevance to the viewer within the image, be that purely semantic information or associations with affective autobiographical content. All this is done in the context of the viewer’s present cultural, social and personal situation, rather than the (distant or recent) past depicted in the image. It is within this network of interactions that our mind fully perceives a photograph.

2. The metamorphogram

Photographic memory

I have shown that photographs do not function as memory. However, so far we have only looked at “traditional” photographs. By this I mean images of scenes external to the camera or film, which exist only for the fraction of a second it takes for the shutter to open and close -usually less time than our brains are capable of perceiving. My artistic practice uses non-traditional photographic techniques, which I have previously used to create visual analogies for philosophical ideas. For example, a photographic sculpture constructed along associationist principles,4 or a series of images using the same source material to depict the reconstructive nature of memory.5 These explorations led to the question ‘can a photograph ever be a memory?’ That is, is it possible to create photographs which are directly analogous to a memory?

I will first define “a memory” with relatively broad yet consciously restrictive terms chosen to replicate, or be representative of, central characteristics of human episodic, autobiographical memory. They are designed to allow easy comparisons between traditional photography and the approach described below, and to allow flexibility within a practical artistic context. Such a memory should: (1) be created as a result of direct perceptual experience, (2) be recorded directly and independently by the object having the experience, and (3) be recallable. The criterion of “direct perceptual experience” is intended to push away from semantic into episodic and autobiographical areas of memory. In addition, a photographic analogy of a memory should (4) function on the same timescale as human episodic memory, to ensure the capture of an experience, rather than a transient external scene. Traditional photographs do not fit these criteria; we may exclude them at criterion (1) by noting that such images are indirectly experienced. The exposure to the scene visualized happened to the film or digital sensor; traditional photographs are secondary interpretations.

To fulfil these criteria and approach this analogy photographically I used a process called cyanotype (blueprint), which uses light-sensitive chemicals and has no requirement for a camera.6 Photograph means “light drawing”, and many of the earliest photographs were cameraless. To create a cyanotype, a photosensitive solution is usually painted onto paper. When exposed to ultra-violet light (sunshine, for example), a permanent blue colour is formed. In contrast to the fractions of a second over which traditional photographs work, cyanotypes can be left to expose for months if needed. This allows the cyanotype to fulfil criterion (4), working on a human-relatable timescale. To fulfil criteria 1-3, I chose to create an approximation of human physical memory. Our capacity to record and recall is held in our brain, contained in our body, with the ability to perceive external stimuli through our sensorium. Through these physical components our experiences are processed, recorded, and made available for recall.

The ‘brain’ of the photograph is the photo-sensitive solution applied to the paper, providing the record-and-recall function. The ‘body’ is the paper itself, which can be given almost any shape we wish through folding. The surface of the paper capable of being exposed to light is analogous to the sensorium, which ‘responds’ to external stimuli by altering the chemicals.

Finally, a critical aspect of this attempt to create a photographic model of an episodic-type memory is that it should result from direct experience. The definition of experience in this case is “an event by which one is affected”; a state or condition to which one is subject. To create an authentic episodic memory I experience an event directly, and translate my perceptions of the event into a memory of that event. The model of creating a cyanotype-memory, below, is based on this human-level process.

Making the metamorphogram

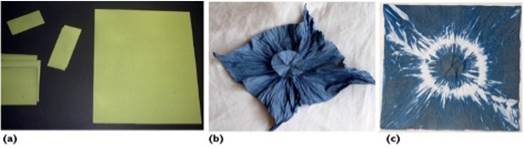

Here I describe the process used as an analogy of human physical form capable of recording its own episodic memories. Paper coated with light-sensitive cyanotype chemicals provides the capacity to record and recall external visual stimuli -the brain of the model (Figure 1a).

Production of a metamorphogram (2019)

Figures 1 a, b & c, a) paper coated with photosensitive chemicals prior to use. (b) An abstract 3D form is folded and allowed to expose. (c) The ‘killed’ final form, showing the resultant image. In white areas no light reached the paper. Blue areas were exposed to sunlight. Greenish-blue areas, such as the central circle, received most light.

The paper is then altered, usually using origami techniques, to give a form specific to the individual model (e.g. Figure 1b). Forms were either nominally two-dimensional, essentially various layers of paper, or three-dimensional, where the form is more-or- less limitless. Now we have a ‘body’ (the form), a ‘brain’ (the light-sensitive chemicals), and the primarily outward-facing, chemical-coated surface(s) of the form comprise the ‘sensorium’ (areas capable of perceiving and responding to external stimuli). It may be helpful to consider the form at this stage as analogous to a new-born creature, with no autobiographical memory, ready to have experiences and create its own episodic memories. The process is not intended to create an equivalent to human memory, but a small- scale analogy of it, with a sensorium and capacity to record and recall information limited to certain visual stimuli. To complete the process and determine whether a photograph can really fulfil the criteria for being a memory it needs to have experience(s) -events by which it is affected- and record and recall them.

Experience was not dictated. That is, apart from early “proof-of-principle” studies, in which the events were somewhat controlled, the locations where forms were placed and what happened to them during their “life” was left to happenstance, and forms were treated arbitrarily. Once created they are placed into the environment (usually inside my home) and may be moved or left still, played with or ignored, forgotten … neither rhyme nor reason dictated the ‘events-which-affect-them’, their experience.

Accumulation of experiences was allowed to continue until some arbitrary external force ended it. As creator, I acted as ‘arbitrary external force’. Some forms lived a few hours, some days, weeks or months. Some had their own adventures (were lost) until the arbitrary external force caught up with them. Through these methods it was intended that every individual form had unique experiences.

Once the experiential time is over, the form is ‘killed’, which is merely the undoing of form, returning it to a relatively flat piece of paper. At this stage any “memory” is statically recorded in chemical changes which have occurred within the surface of the paper. To complete the process, the “memory” is recalled by washing the paper in water to remove any unused chemicals and leave an extremely light- and colour-fast final image (Figure 1c). I have named the photograph created by this process -transforming paper into a distinct form which then returns to a flat image- a metamorphogram.

Experience-dependent photographic memory

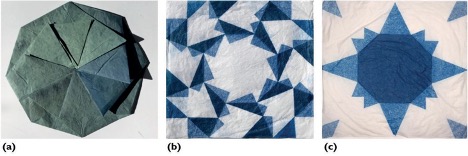

We now have a photographic process adapted to create a loose analogy of autobiographical memory as instantiated in the human body. Forms are allowed to have ‘subjective’ experiences, events-which-affect-them, which creates the final image. The following simple demonstration examines the crucial formative role of direct subjective experience in creating the final image. Two identical pieces of tissue paper were coated with the same batch of chemicals at the same time, and folded into exactly the same form; a flat origami called a “tato”, which has all its folds on one surface (Figure 2a). These were placed in sunlight adjacent to one another for the same length of time; in this case several days. The only difference between the two forms is that one was placed folded-side up, while the other is folded-side down. Their creation and “life experience” is identical in every way, with “killing” and recall also identical in each case.

The influence of experience on the visual image recorded by a metamorphogram (2017)

Figures 2 a, b & c, Coated tissue paper was folded into the tato form (a) and left to gain experience either folds-up a) or folds down (c). All other variables were identical. (b) and (c) are the final ‘killed’ images from each form.

The images produced are dramatically different (Figures 2b and 2c). We can say one is the experience of ‘being-a-tato-face-up’ and the other the experience of ‘being-a-tato-face-down’. Their single difference in perceptual experience directly and strikingly affected the image recorded of their otherwise identical ‘life-as-a-tato’. We may imagine the analogous situation of two people standing back-to-back; they would have different perceptual experiences, and therefore different memories, of a particular event.

We are now able to ask whether these finished metamorphogram images fit the previously given definition of a memory. Are they (1) created as a result of direct perceptual experience? Yes, and the above experiment shows that the subjective nature of the experience affects the final image “memory”. Was the image (2) recorded directly and independently by the object having the experience? Yes, as no external force, device or process was required for recording the image (traditional photography normally requires a camera and human operator or other physical mechanism to choose and trigger exposure and recording). Was the recorded information (3) recallable? Yes, we may consider this as analogous to me asking somebody to recall an event. I trigger and perceive the recalled memory, but the recall is independent from me. For a metamorphogram, I ‘ask’ it, for example, what it was like to ‘be-a- tato-face-up’. My external stimulus ‘initiates’ the recall (and in this case physically aids recall by washing the paper), but the memory recalled is entirely specific to, and dependent on, what the object had recorded during the experience. Finally, the image was (4) created over a human-relatable time period, and so is much more reflective of human memory than the single instant recorded in a traditional photograph. This allows the conclusion that a metamorphogram image is a photograph which is directly analogous to a memory, based on these criteria.

Metamorphogram memory

I will now give further examples showing how the images created relate directly to the perceptual information recorded during an individual object’s experience. We must note that metamorphograms are highly limited in both their perceptual and recording capabilities. They can only record using the chemicals on their surface and, to some extent, perhaps with their physical ‘body’; the paper from which they are formed.

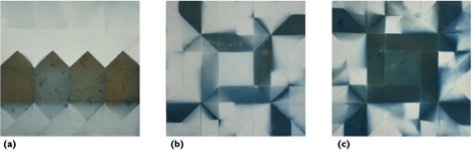

In a project working with people living with dementia, 3D origami shapes made from chemical-coated paper were fitted with recording devices.7 Participants could tell their thoughts to the boxes, which would ‘remember’ what they said, while the box itself created its own memory of its time (weeks to months) living with the person. Some of the images are shown in Figure 3.

With practical understanding, these metamorphograms can be ‘translated’ in the context of the known experience. For example, in Figure 3a:

the visible folds and the pattern of coloured areas show this was a cube,

the overall colour has become a gold-green, which indicates that this box was ‘alive’ in a bright place for several weeks at least,

the far right, darkest in colour, was facing the light,

- the triangles below the gold squares are much paler than those above the squares due to experiencing much less light, and so formed the bottom of the box, and

most interestingly, the random marks and smears in the coloured areas show us that this box lived in the participants kitchen, near the sink. The marks are splashes from the washing-up water which altered the chemicals in those places.

Metamorphogram images from the Memory Box project (2018)

Figures 3 a, b & c, Box (a) has recorded both visual and physical stimuli, as well as multiple interactions with its external environment. Boxes (b) and (c) show again the influence of experience on the final image / memory produced.

Together these visual characteristics constitute the memory of this metamorphogram’s ‘life’ as a box-form in this person’s house. Unlike a traditional photograph it has not simply recorded a transient moment external to itself. It has, within the limits of its capacity to do so, recorded its direct perceptual experiences -formation, placement, duration, light exposure, orientation, and even the consequences of interactions with others.

In Figures 3b and 3c we see the visual memories of two boxes with the same initial form, but which spent their lives with different people. The box on the left (Figure 3b) was in a fairly bright place, with light coming mostly from the right, and shows a splash where some tea was spilt. The square in the centre was the bottom of the box, and so is white.

The box on the right (Figure 3c) shows more colour, and the colour is relatively even. It has had more light, and from all sides. Interestingly, the square in the centre is blue, which means the bottom of the box has been exposed to light. It happens that the participant moved house during the project, so the box experienced movement including being turned upside down for a while. The box recorded that experience, and our process has recalled the memory of it in visual form: we can visualise the biography of the form. This is a self-created biography, distinct from the biographies ascribed to personally or culturally important objects predominantly through human agency, as described by, for example, Hoskins (2005).

We seem to have a photograph which fulfils our criteria for memory. But what sort of memory? The analysis above also identified experience recorded in the physical media of the object itself, i.e. folds in the paper. Let us deal with this first. We may argue that folds in the metamorphogram constitute procedural memory.

The folds made to create the form remain, and often show which direction the paper was folded. A competent origamist could refold the form from these creases, but the paper could not refold itself, arguing against procedural memory. We may instead argue that folds are another visual aspect of our analogy to memory, but we have defined the paper as the form’s ‘body’ rather than part of the light-sensitive sensorium. I conclude that these folds represent ‘birth marks’ or scars. They act as reminders of an experience, rather than a memory of that experience.

We are left with our photographic image. What kind of memory is it analogous to? As the image does not show non-autobiographical, non-experiential factual information, I exclude it being analogous to semantic memory. This leaves episodic memory. Some aspects of the metamorphogram relate to specific episodic experiences, such as the tea splash in Figure 3b. The washing-up splashes in Figure 3a are likely due to repeated incidents (note that the experience of being splashed is recorded by the photographic ‘sensorium’; these marks are not mere ‘stains’ masquerading as a memory), and so result from multiple individual episodic experiences.

The colour of each image also arises due to the overlaid memory from multiple episodic experiences of ‘being-in-a-particular-place’ and recording the specific amount of light (dependent on direction, intensity etc.) perceived by the sensorium each time. A little colour from one dull day, overlaid with more colour from the next, brighter day, colour on different sides when moved for a day, and so on. Together these experiences result in an image which is a composite memory built up from many individual ‘episodes’.

Metamorphograms are not, then, engrams or memory traces. They do not show the multiple aspects of a single experience, unless we consider their entire ‘life-as-a-form’ as a single experience. They are instead an amalgamation of all the recordable perceptual experience perceived by the form during its entire ‘lifespan’. The analogy here would be to every episodic memory retained by a person, overlaid one on top of the next.

3. The individual and cultural memory

In this section I set out how artistic explorations led from initial examinations of individual memory to finding connections between individual and collective memory. I show that bi-directional agency exists between individuals and certain social groups to which they belong, such that (1) individuals can directly influence the nature of a collective memory, and (2) that collective memory can influence individuals at the level of their autobiographical ‘self’.

I have shown that, while traditional photographs are tools rather than memories, it is possible to create a photographic image analogous to memory. These metamorphogram images appear to comprise a ‘lifetime’ of episodic memories in a single expression. Applying artistic licence, I now take a metamorphogram’s memories at the time of its ‘killing’ to be somewhat comparable to an individual ‘self’, if it were possible to visualise such a thing. Each metamorphogram is unique due to its specific and subjective recorded experience, despite sharing features such as creative process, form and sensorium with other metamorphograms.

My interest in origami led me to explore what I considered to be ‘cultural memory’, long before I had read any philosophical or sociological definitions of what cultural memory might be. Naively, I thought the practice of origami may itself comprise a cultural memory. These early inquiries coalesced into one two-pronged question: How does cultural memory affect the individual, and how does the individual affect cultural memory?

At this stage, I had no definition of cultural memory in mind. However, in deciding that I could consider each metamorphogram as representing a unique individual, I was able to explore the relationship between cultural and individual memory through art.

There is a Japanese folk tale surrounding the origami crane, known as the orizuru (ori - paper; tsuru - crane). The red-crowned crane, as a bird, has various symbolic meanings in Japan, including longevity and authority. The origami version long predates its appearance in the first printed origami book, Hiden Senbazuru Orikata of 1797 -origami has existed in Japan since around 600AD. Pre-second world war, the act of folding 1000 orizuru- called senbazuru -was thought to bring the folder a boon, such as long life, good health, or a wish. After the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a girl called Sadako Sasaki developed leukaemia. She decided to fold senbazuru to wish away her illness, but died while 8still folding them (Sasaki & DiCicco, 2020). As a result of the perception of her experience by others, the cultural meaning of senbazuru has been altered. It has become a symbol of hope and peace; hundreds of thousands of cranes are delivered to shrines at Hiroshima and Nagasaki every year. Senbazuru projects for peace are now abundant across the world.

This story led me to construct two hypotheses. First, that an individual could directly affect cultural memory; in this case, expanding or altering the meaning of a long-standing cultural symbol. Second, that some cultural memories could affect individuals at the level of their autobiographical ‘self’; people temporally and spatially distant from the original event are affected enough to fold one thousand cranes, use the imagery and symbolism, and encourage others to do so - enough to become a lesser or greater part of ‘who they are’.

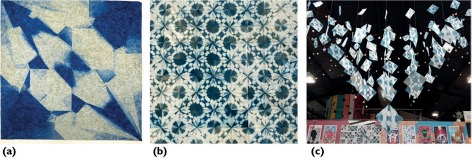

To test these hypotheses through art I decided to fold my own senbazuru, where each of the 1000 cranes would become a metamorphogram.9 That is, cranes were folded from chemical-coated paper, allowed to ‘live’ according to the principles set out in section 2, above, and then ‘killed’ to reveal the the visual memory of their ‘time-as-an-orizuru’. Although each of the 1000 metamorphograms was formed in an identical process, each was also unique as a final image (Figure 4a), representing the recorded experiences of a unique individual, and many of those experiences were shared across the 1000 individuals. I therefore had a group of individuals with shared experiences analogous to some sort of ‘cultural’ memory, and began to explore the relationships between them.

In Cliques and Networks (Figure 4b) 81 crane metamorphograms were arranged together. The individual metamorphograms cannot communicate with each other, so the relationships formed are based entirely on the memories they recorded while ‘alive’ in crane form. The patterns which appear infer how our personal experiences lead us to form a range of connections with others, and together those interactions form something new. Small groups of individuals together create circular ‘cliques’ where aspects of their individual memories meet. Other parts of the individual images form an extended diagonal grid, or ‘network’, connecting individuals well beyond our immediate social circle or clique.

Exploring interactions between individual memory and collective or cultural memory (2019-20)

Figures 4 a, b & c, a) An individual orizuru metamorphogram. (b) Cliques & Networks collage. (c) Six Degrees of Separation installation of over 100 individual metamorphogram cranes.

The artwork visualizes through these linked individuals the concepts that each individual has its own memories; that some memories (i.e., experiences) are shared with a close social group, and other memories or experiences are shared on a much wider social level.

The second work shown is a hung installation entitled Six Degrees of Separation (Figure 4c), which has individual metamorphograms hung in five grouped layers, with the sixth layer to be provided by the viewer. The title arises from the popular, yet inaccurate, notion that any individual is connected to any other via no more than six social interactions. The five layers of individuals are ‘connected’ via their shared experience, which has resulted in them appearing very similar to one another. The work asks of the viewer, are you able to connect as the sixth layer, or do you lack a shared experience which would allow that connection? Individually recorded shared experience - a form of cultural or social memory - allows us to come together as a social group. The experiences gained within the social group may then feed back and become part of each individual’s memory.

These works, created naively, without reference to literature on cultural memory, seemed to support the idea that a memory of an event experienced by a cultural or social group could link that group together, even though the event was experienced at an individual level. Further, that the coming together of individual memories created something new, new connections, or social structures. Further, that it was each individual’s memory that combined to create these new things. The model represented by the artworks is certainly weak, almost barely there. However, it opened a pathway down which the idea developed.

Considering these works strengthened my conviction that the original linked hypotheses (1. that an individual can directly affect cultural memory, and 2. That cultural memory can affect individuals at the level of their autobiographical ‘self’) were worthy of a more rigorous examination. To do this, two significant issues needed to be addressed. First, the art-based models only indirectly address the hypotheses. At this stage their validity is based on extrapolation and artistic inference. A stronger, real- world example is required. Second, no definition of ‘cultural memory’ has been given here. Since various types of cultural memory exist in philosophical and sociological literature (see, e.g., Adams, 2019; Manier & Hirst, 2008; Wang, 2021), any model needs to be tested against them.

City or United?

While the senbazuru example offered a glimpse of something, a more concrete example is needed to fully examine whether there exists a bidirectional flow of influence between individual and what, lacking a more specific term at this point, I will continue to call cultural memory until I compare it with extant models.

The hypothesis indicates that I should seek a social or cultural context to which individuals contribute, and by which individuals are influenced at the level of their autobiographical memory or ‘self’. I choose to use as my model supporters of English Premier League Football clubs, although many other organisations, clubs or social groups would substitute.

Major football clubs are large businesses, their identity and product branded and sold around the world. However, football clubs require supporters, and the supporters’ experience of football is far from institutionalized, and extremely social. Of importance for later comparisons with other forms of cultural memory, relationships between individual fans do not require familial, employment or other common social links. While support for a specific club may ‘run in the family’, with successive generations supporting the same team, intrafamilial rivalries are also far from uncommon (I am a Liverpool fan, which antagonizes my father, a Manchester United fan). Using this model, I set out how supporting a football team creates a cultural memory influenced by individuals within that culture (the supporters), and how supporters are in turn influenced by being part of this cultural group.

The act of supporting your team is ongoing, and not restricted geographically or temporally, e.g., it is limited neither to the days matches are played, nor to the stadia, cities or even countries in which the matches take place. Supporting is a very social activity generally characterized by oral storytelling, semantic knowledge sharing, and reminiscence about events and characters associated with a club down the years. The matches themselves are, for the supporters, shared, repeated, very emotive experiences whether experienced in the stadium, in a local pub or half way around the world watching on television. The ‘I was there’ (or, for distant fans, ‘I witnessed’) motif of storytelling adds weight and authority, and interesting details heard from one source may be incorporated into the next telling, adding to the cultural memory.

Songs and chants associated with the team are sung communally, and are often created by generally anonymous individual supporters. This is our first example of individuals having agency to affect a shared experience. It takes a single supporter to start a new song eulogising a player, and that song may be sung for decades; indeed many songs sung in football stadia have been around for generations. As a recent example, a pop group enlisted two celebrity supporters to sing a song in support of England at the European Championships in 1996. The lyrics drew heavily on cultural memories surrounding the English national team, and immediately engaged supporters.10 The ‘Three Lions’ song is still sung, now by supporters who were not alive in 1996. The imagery and the words ‘three lions’ have become a central part of their shared memory.

There is a strong trans-generational aspect to this social support activity; contemporary supporters sing songs and tell stories of players and events they have never witnessed, or quote the wisdom of managers who died before they were born. Taking part in these activities does not require any prior links to any other participant. What is needed is (1) to self-identify as a supporter of that team, (2) to be identifiable by other participants as a supporter of that team, and (3) to share in the cultural memories of the team as embodied by the supporters.

Symbols, therefore, constitute a crucial part of the social experience. They not only allow members to identify each other, but can themselves form part of the shared cultural memory. While the business of the club includes selling merchandise such as team shirts, much of the most iconic symbolism is generated by supporters. Some of the most potent examples are flags and banners. For example, many created by Liverpool fans celebrating triumphs of the 1970s and 1980s are still displayed by supporters in the stadium and revered by their supporters elsewhere specifically because of the shared cultural memory for which they serve as reminders. New banners are created and displayed regularly, offering opportunity for any individual to create something which will become part of the evolving cultural memory of their club.11

Football supporters often define themselves, or at least an important part of their self, as a ‘Liverpool fan’ or a ‘Chelsea fan’. Anyone ever asked by a Mancunian the dreadful question ‘City or United?’ will feel the importance of their answer to the identity of the questioner. Are you one of us, with our shared history and understanding? Or are you one of them? One whose experiential memories - and identity - are in direct opposition to our own?

In these ways the culture is not only rich and vibrant for its members, but is also reliant on their participation in its generation and maintenance in order for it to continue as the same-but-not-the-same thing. By this I mean that the shared memory maintains a consistent yet constantly reconstructed composition by being comprised of shards derived from every member of the culture. It relies on distributed remembering and may be an example of an exceptionally widespread ‘transactive memory system’ (Heersmink & McCarroll, 2019, p. 99), where each individual remembers overlapping parts of the whole and each supports the memory of the other.

Looking at the model above we have a large group of geographically disparate people joined by a shared cultural memory powerful enough that these people consider it, to lesser or greater extents, part of their autobiographical selves or personal identities. The cultural memory is not static, but is maintained, renewed, expanded and transmitted across generations by the supporters themselves through participation in it. It is this requirement for participation which allows individuals to modify the cultural memory for all members. This model therefore appears to fully support the bidirectional relationship between individual and cultural memory hinted at by the senbazuru works. It offers multiple and ongoing opportunities for individuals to influence the nature of the shared memory, and the shared memory can become a significant aspect of the autobiographical ‘self’ of individuals within the collective.

Sociobiographical memory

I began by questioning the nature of photographs and how we perceive them, showing that traditional photographs are not memories. From trying to create a photograph which mimics aspects of memory came the metamorphogram; an object which takes a ‘photograph’ of its own experiences as a unique visual expression of ‘self’. Using the metamorphogram to create many ‘individuals’ with shared experiences begged questions of shared memories and a stream of influence which flows both ways.

This long and interesting journey as an artist entering the philosophical world has exposed another bi-directional relationship. Interrogating photography with philosophical questions proved extremely valuable to the development of my artistic ideas. Interrogating philosophy through photographic art has led me to questions I had not previously considered. In the first part of this section I used art to develop a hypothesis around a form cultural memory which (1) can be directly affected by individuals, and (2) can affect individuals at the level of their autobiographical ‘self’.

I then set out the Football Fan model, which appears to be a real-world example of this form of cultural memory. One may be able to think of many groups of people whose personal and shared identity is similarly entwined; punks (and steampunks), K-pop fans,12 and MAGA enthusiasts (particular grass-roots supporters of Donald Trump) would fit equally well. In this final part I examine what sort of cultural memory are we seeing among these groups by comparison with existing definitions.

Empirical research shows that cultural context influences autobiographical memory. That is, self-identity is modified by shared cultural practices. Human groups seem predisposed to create social or cultural memories. Mnemonic practices, such as oral storytelling and behavioural habits, maintain and spread cultural memory across the generations. These mnemonic practices directly influence aspects of individual self- identity such as moral boundaries and taboos (for a review and examples see Alea & Wang, 2015; Wang, 2021; Zhang & Cross, 2011). However, in this sense cultural memory provides the context into which autobiographical memory is placed and reconstructed. Wang describes memory as being ‘saturated in cultural context’, with culture influencing what details are selected for remembering (Wang, 2021). ‘Cultural memory’ in this form may be thought of as a series of learned behaviours, morals and contexts; scaffolding onto which autobiographical memory is built. The shared experiential memory of a football fan would be constructed within such context, but is not this form of cultural memory. In revisiting the works of Ricoeur, Suzi Adams (2019) describes Jan and Aleida Assmanns definition of Cultural Memory, which I capitalize to distinguish it from earlier uses. Adams calls Cultural Memory the ‘institutionalized heritage of a society’, the triad of remembered / forgotten / not forgotten (Assmann, 2006) information and artefacts which contribute a formative role in creating a ‘collective identity’ (Adams, 2019). The process of institutionalization - choosing which information is remembered - is generally carried out by a very small, select group, independent of input from almost all individuals within the society. The resultant collective identities appear prone to being, as Jan Assmann described all collective identities, ‘products of the imagination’, or abstracted stereotypes. They apply to large groups, nations or religions for example. Individuals are given little choice as to the nature of the collective identity of which they are a part, and the memories are not embodied within most people. Therefore, the Assmanns definition of institutional

Cultural Memory does not fit our model.

Communicative memory, which Adams (2019) suggests is very similar to Halbwachs’ ‘collective memory’, is described by Aleida Assmann as being about the everyday or the mundane, existing within living generations of people, often communicated orally. Retention beyond these limited temporal horizons requires it to become part of cultural memory. Assmann goes on to describe social memory as a part of communicative memory (Assmann, 2006). Social memory is about everyday life, intergenerational and based on lived experience. However, this sort of memory belongs to relatively small groups, such as families, work colleagues and so on. It addresses memories with social functions, providing contextual and socially useful information such as remembering jokes and the personal stories of others. Communicative memory, and subgenres within it, seem close to our football supporter model. However, communicative memory lacks a defined and consistent overall narrative shared by all members. Neither does communicative memory, being predominantly functional, appear to impact individuals at the level of their autobiographical self.

These existing definitions of cultural memory as a contextual scaffold, as institutional Cultural Memory, or various shades of smaller-scale communicative memory do not cover all social contexts. Whole areas of social interaction and lived experience encompass shared memories which fall outside of these systems, none of which offers agency to individuals with regard to shaping shared memory.

The shared memory exemplified by football supporters is not behavioural or generally unconscious as cultural contexts are described to be by Wang and others. It is neither tangential to nor abstracted from individual experience, in sharp contrast to institutionalized Cultural Memory. Instead it is direct and participatory, active and evolving. Strong autobiographical-yet-socially-shared memories are created and reinforced in specific social contexts. These memories are not semantic, having affective episodic content which is generally similar for all members. In this sense, there are strong similarities to the ‘collective episodic memory’ described by Manier & Hirst (2008, p. 257). Though developed entirely independently, both I and Manier & Hirst use football fans as an example. They note, for instance, that sports fans may form a collective memory of a specific event. However, the current model not only expands on this thinking, but differs from it significantly. The striking feature of this form of cultural memory -a narrative shared by all members of a group- is that it is malleable by individual effort. Its main defining characteristic may be its effect on individual self-identity, an effect produced by shared, direct and valued experiences. In light of the bi-directional influence between socially shared experience and autobiographical content, I propose ‘sociobiographical memory’ as a suitable descriptor.

4. Conclusion

This paper is more about a journey and a relationship between art and philosophy than it is about any philosophical conclusions. Having begun this paper examining our perception of photographs, how have I arrived at a point where I am discussing forms of cultural memory? The path began with John Sutton’s Philosophy and memory traces (Sutton, 1998). When developing the metamorphogram my naïve, art-led interpretations no longer seemed appropriate to answer the questions arising from the process. What exactly were these images I was creating? And what exactly was I trying to represent? Sutton’s writing showed the direction in which the answers might lie.

Through further reading of philosophical literature, I understood why traditional photographs are not memories, and why the metamorphogram might be. The explorations of philosophers, psychologists and sociologists allowed me to set definitions against which artistic ideas could be tested. They provided a structure supporting the artworks themselves. Most interestingly, the art developed in this context provided a visual language to communicate philosophical ideas to lay audiences outside of an academic context. Art driving engagement with philosophy, and philosophy informing art is, in my experience to date, a productive and generous two-way relationship.

In a world where photographs are everywhere, it can only be of benefit to understand our relationship with them. The concept of photographs as memories may be wrong, yet it is deeply embedded as a cultural metaphor and unlikely to change. However, Barthes’ deeply personal reflections on photography have been built upon to show that we actually use photographs as tools ranging in power from mnemonic aids, to evocative objects which may become a physical part of an extended memory system (Heersmink, 2020). These developments in our understanding are already inspiring novel ways of helping people with memory problems.13

Photography, triggered by philosophical literature, then led me to explore cultural memory. Currently, ‘sociobiographical memory’ is an idea awaiting further development. However, the process of trying to understand what I was showing people (see Figure 4) begs questions of how philosophy relates to the real world. I found no extant definition for a myriad of everyday examples of shared memories which constitute part of an individual’s autobiographical self. There exist mind-boggling numbers of self-creating, self-organizing groups, both short-lived and long-lived, which seem to fit preliminary criteria for sociobiographical memory. Modern technology means geographical limitations on forming social interactions with like-minded others, commonplace until the last decade or two, no longer exist. ‘Furries’, goths, Wall Street Bets14 and other dynamic, almost exclusively online groups, and any number of comic and film-related fandoms are just some that spring immediately to mind. Their lived experiences and shared culture, and how these affect individual self, seems to be relatively unexamined philosophical territory, outside the domains of existing Cultural Memory.

In summary, communicating philosophical insights through art is one way to share these important discoveries about who we are with a much wider audience. Though only a sample of one, my practice has gained immeasurable benefit from working within philosophical contexts. From introducing concepts of memory into origami workshops, to better understanding the lived experience of people with dementia, philosophy adds something valuable to each conversation, and I am grateful to have stumbled into it.