Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Suma Psicológica

Print version ISSN 0121-4381

Suma Psicol. vol.17 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2010

CRITICAL REVIEW OF EMPIRICAL RESEARCH DEALING WITH THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN OPTIMISTIC TENDENCIES AND HIV RELATED BEHAVIORS

REVISIÓN CRÍTICA DE INVESTIGACIONES EMPÍRICAS SOBRE LA RELACIÓN ENTRE TENDENCIAS OPTIMISTAS Y CONDUCTAS ASOCIADAS CON EL SIDA

Carolina Santillán Torres Torija and María del Rocío Hernández-Pozo1*

1 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, FES Iztacala, México

* This study was the result of a research seminar developed under the supervision of the second author during the doctoral training of the first author.

Correspondence concerning this article should be sent to Carolina Santillan, carolina.santillan@comunidad.unam.mx, or to Rocio Hernández-Pozo, herpoz@unam.mx.

Recibido: Julio 7 2010 Aceptado: Diciembre 15 2010

ABSTRACT

Many variables related to risk of HIV infection, progression of the disease and adherence to antiretroviral drug therapy have been studied from different approaches. This review incorporates a group of studies including optimism as a variable related to Positive Psychology and HIV/AIDS, to explain how it interacts with: sexual risk behaviors, disease progression and adherence to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. Refereed academic journals published from 1994 to 2009, were accessed from the EBSCO database. Subject Terms were related both to HIV and optimism. Articles were arranged into three classifications: infection, disease progression and ARV therapy adherence. The review included 32 articles carried out mainly in the USA. Most articles showed significant relationships between optimism and risk behaviors, disease progression and ARV adherence. This study concluded that more research in evaluation of optimism, and optimism related interventions should be made to disentangle the complex relationship it has with sex risk behaviors, disease progression and adherence to ARV Therapy. Moderate optimism appears to be a predictor to health related sexual behaviors.

Keywords: optimistic tendencies; HIV; AIDS; sexual risk; adherence; disease progression.

RESUMEN

Muchas variables relacionadas a los riesgos de infección por el VIH, la progresión de la enfermedad y la adherencia a la terapia antirretroviral se han estudiado desde diferentes puntos de vista. Esta revisión presenta un grupo de estudios que incluyen a la variable optimismo, relacionada a la Psicología Positiva y el VIH/SIDA, para explicar la manera en que interactúa con los comportamientos sexuales de riesgo, la progresión de la enfermedad y la adherencia a la terapia antirretroviral (ARV). Se consultaron revistas académicas arbitradas publicadas en el período 1994-2009, en la base de datos EBSCO. Los términos seleccionados fueron VIH y optimismo. Se organizaron los artículos en tres categorías: infección, progresión de la enfermedad, y adherencia terapéutica a los ARV. La revisión incluyó 32 artículos de investigación conducida principalmente en E.U. La mayoría de los artículos mostraron relaciones significativas entre la variable optimismo y las conductas de riesgo, la progresión de la enfermedad y la adherencia ARV. El estudio concluye que se requiere más investigación en evaluación de las tendencias optimistas, e intervenciones relacionadas con optimismo para esclarecer la relación compleja que guarda con las conductas sexuales de riesgo, la prognosis y la adherencia a la terapia ARV. El optimismo moderado parece predecir comportamientos sexuales saludables.Palabras clave: tendencias optimistas; VIH; SIDA; riesgo sexual; adherencia; progresión de la enfermedad.

Since the discovery of a rare and often fatally rapid form of cancer (Kaposi's sarcoma), men having sex with men, eight of which died within 24 months after being diagnosed (Altman, 1981), huge amounts of financial and human resources have been allocated for the study of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and progression of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Health professionals have developed models to explain the course of the disease: acute infection, the defense that makes the immune system, CD4 cell loss and immune response, and establishment of AIDS which eventually leads to patients, victims of opportunistic infections to death.

Health Psychology has tried to understand the related variables to preventive behavior, the effects of diagnosis on the individual's mood, as well as variables related to adherence to treatment, disease progression, and elaboration of the loss. Some of these variables are information, motivation, behavioral skills, self-efficacy, self-regulation, social support, among others. Nevertheless behaviors associated with infection prevention, disease progression of HIV / AIDS and adherence to antiretroviral therapy can be viewed from a new field: Positive Health Approach. In this regard Martin Seligman talks about a positive health status:

"The positive health describes a state beyond the mere absence of disease it is possible to define and quantify... positive health predicts an increase in longevity, decreased health costs, provides better mental health in old age, and improves the prognosis when the disease arrives." (Seligman, 2008, p. 3)

One concept incorporated by Positive Psychology is that of explanatory style, i.e. how a person interprets the situations that happen, including success or fail. There are two explaining styles: the optimist and the pessimist. In general we can say that the former conceives that when the person is successful, tends to attribute this to himself and when it fails it tends to attribute it to the circumstances. By contrast a person with a pessimistic explanatory style attributes to himself failures and interprets success to external circumstances or luck. Carr (2007) mentions that people having a pessimistic explanatory style tend to develop more depression when confronted with stressful events.

A great number of researchers have given to the task of finding how optimism works, sometimes as a protective variable, sometimes as a perilous antecedent of an individual's coping style. Many say that in case you get sick, optimism is useful for psychological adjustment, Rasmussen, Wrosch, Scheier & Carver (2006) assessed optimism in patients with a health threat such as Coronary Disease, Cancer and other health contexts like HIV, and reproductive issues. Their findings show that apparently "optimism is beneficial when people face a threat to their health" (Rasmussen et al., 2006, p. 12). In their work, Taylor & Armor (1996) showed that in men who have tested seropositive for HIV, a relative optimism in the ability to fight against AIDS was related to better psychological adjustment. Finally Tsevat et al. (2009) describe in their research how optimism was associated with patients feeling that life was better after being diagnosed with HIV (because they found a new purpose in life, or changed lifestyles).

Other research, like that of the members of the International Collaboration on HIV Optimism (2003) examined HIV optimistic tendencies among gay men in four industrialized countries. They found that the most consistent association was between HIV optimism (perception of severity and susceptibility) and high-risk sexual behavior. In three of the four countries, mean optimism scores were higher for men who reported unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) with a casual partner than for men who did not report any UAI, although the authors could not establish a causal relationship. It seems that although few of the gay men who participated in this study did not show optimism towards new Highly Active Antirretroviral Therapy (HAART), sexual risk behavior was associated to a low perception of severity of the HIV infection and low perception of being susceptible to one's infection. This results match with the work of Brennan, Welles, Miner, Ross & Rosser (2010), and Sherr et al. (2008) who, each on their research, found that unsafe anal intercourse among HIV-Positive men and complex adherence behaviors were associated with being optimistic about treatment, respectively.

One of the possible well known explanations is provided by Folch, Casabona, Muñoz & Zaragoza (2005): they explain incidence of non-safe sexual practices in association with the optimism raised by the HAART Era. The authors explain that a change towards non-safe sexual behavior could be partly explained to the extent that the emergence of HAART has diminished the perceived death threat toward HIV infection patients had 10 years ago.

Approaches like the ones of Segerstrom (2005) give light to more comprehensive explanations to understand the complex phenomenon of optimism. This author suggests that dispositional optimism may affect immune system depending on the circumstances; if the person faces brief stressors, optimism will appear to be protective, however if the stressor is prolonged, optimism will endanger immune functions. Also, Segerstrom explains that the stressor's controllability will define the role optimism will play. In the case of HIV infection, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) face two moments: the diagnosis (an acute stressor) and living with the disease (a chronic stressor). Dispositional optimism results in higher engagement in the short term diagnosis, and the cost to be paid for the optimistic strategy of engaging difficult stressors, is reflected in higher cortisol as well as lower cellular immunity. But in the long term living with HIV/AIDS, a chronic stressor, and having a high dispositional optimism can lead to better outcomes.

As we have reviewed, two kinds of optimism have been assessed in HIV related behaviors: dispositional optimism and optimism toward treatments. Doubts persist regarding optimism's influence in health related behaviors. The present work aims to make a quantitative review of the work that has been made from Positive Psychology perspective. Specifically the review contemplates the optimistic tendency as a variable associated with HIV related behaviors. We intend to contribute to a better understanding of how optimism relates to risk taking behavior, adherence and disease progression.

METHOD

Data Sources

The present review includes studies published from January 1994 to July 2009. The studies were obtained via a restricted access to EBSCO electronic database. The exact search strategy included terms related to Positive Psychology (optimism, and AIDS, HIV).

Study Selection

The reviewers screened the titles in the bibliography, and summaries (abstracts), if available, to identify and obtain those studies who deserved full text review. In case there were differences in the evaluation of articles, they were discussed between the reviewers.

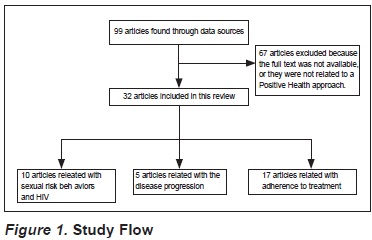

The search was carried out only with studies associated to the Theoretical Model of Positive Psychology and HIV related behaviors (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were: a) That the study reported a Positive Psychology Theoretical model, b) That the study included a Positive Psychology based Instrument or Interview c) That the population included in the study was HIV Positive, or was assessed risk factors associated with HIV infection.

Data Extraction

For each eligible study, one reviewer extracted the features of the patient population, source, sample characteristics, purpose of the study, instruments and results. Another reviewer confirmed each extraction.

Summary of data

The eligible studies differed substantially in the number of participants, age groups, measurements and results. For the analysis they were arranged in three groups of publications: a) Optimism as a mediator variable in sexual risk behavior, b) Optimism as a mediator variable in adherence to Antirretrovirals (ARV), and c) Optimism as a mediator variable in the disease progression. However, there was a difference in methodological approaches and designs among them.

RESULTS

The electronic search returned 99 citations, 40 of which were judged to merit full-text review. A total of 32 articles met the inclusion criteria and are presented in the present study. Most of the studies were made in English speaking developed countries / cities (n = 28), the most frequently used evaluation instrument was the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). We did not find studies held on Spanish speaking countries.

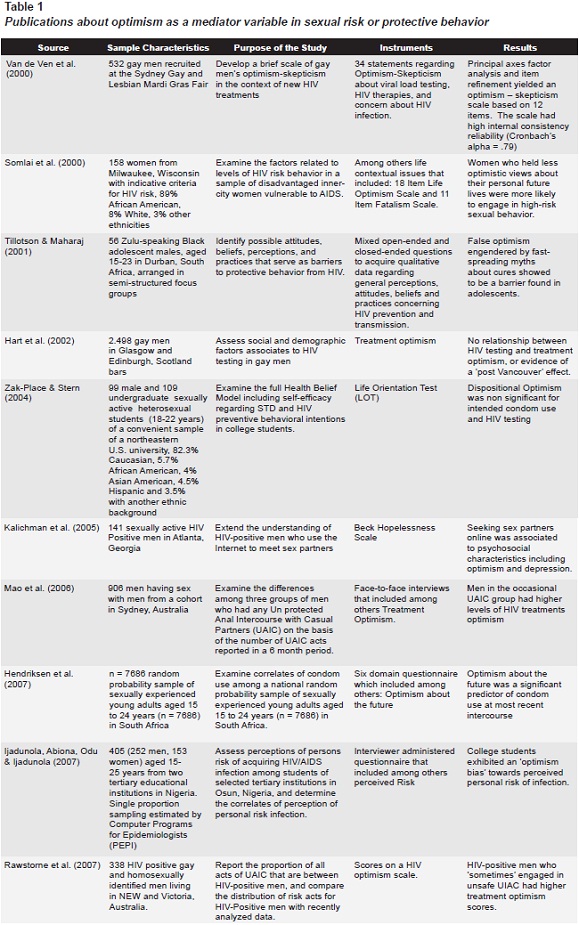

Tables 1, 2 and 3 show the studies arrangement included in this review and describe pertinent information regarding methodological particularities of each study. For the instruments, and results section, only instruments and outcomes related with Positive Health measures are included.

Optimism as a mediator variable in sexual risk or protective behavior

Of the retrieved studies from the electronic search, a number of 10 studies were eligible to be included in this section. A total of 12.928 participants were included in sexual risk or protective studies regarding Optimism, with a minimum number of 56 participants and a maximum of 7.686. Five out of ten studies included men having sex with men, four included female and male students or adolescents, and one included only adult women. Three studies were held on Australia, three in the United States, two in South Africa, one in Nigeria and one in Scotland. The main evaluation approach the studies used to obtain their data was either quantitative (n = 9) or qualitative (n = 1).

All the studies included in this section used evaluation instruments related to Optimism towards sexual risk or protective behavior. Studies listed on Table 1 reproduce the progress science does when approaching a new field of knowledge: Assessment, extending the understanding through examining diverse factors, and developing instruments.

Seven out of ten studies mainly examined factors related to HIV risk behaviors: Somlai et al. (2000), in a sample of disadvantaged inner-city women vulnerable to AIDS; Zak-Place & Stern (2004) examining self-efficacy regarding STD and HIV preventive behavioral intentions; Tillotson & Maharaj (2001) identifying possible attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and practices that serve as barriers to protective behavior from HIV; Kalichman, Cherry, Cain, Pope & Kalichman (2005) extending the understanding of HIV-positive men who use the Internet to meet sex partners; Mao et al. (2006) examining the differences among three groups of men who had any Unprotected Anal Intercourse with Casual Partners (UAIC); Hendriksen, Pettifor, Lee, Coates & Rees (2007) observing correlates of condom use; and Rawstorne et al. (2007) reporting the proportion of UAIC acts and their relationship with treatment optimism scores.

One of the studies included in Table 1 is dedicated to develop a brief scale of gay men's optimism-skepticism in the context of new HIV treatments (Van de Ven, Crawford, Kippax, Knox & Prestage, 2000). Two studies have as a main objective, assessment: One assesses social and demographic factors associated with HIV testing in Gay Men (Hart, Williamson, Flowers, Frankis & Der, 2002), while the other assesses perceptions of personal risk of acquiring HIV/ AIDS infection among students.

Two studies showed no relationship between the optimism variable and the preventive behavior (condom use and HIV testing), and eight out of ten studies demonstrate Optimism better predicted risk behavior. Studies showed that false optimism about cures, optimism 'bias' towards risk, optimistic views about personal life, and optimism towards HIV treatments was a predictor of risk behavior that included unsafe UAIC among HIV positive gay in Victoria, and Australia; optimism bias towards perceived personal risk of infection in young people living in Nigeria; seeking sex partners online in men having sex with men in Sydney, Australia, and engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors in a 98% African American sample of women from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Protective behavior (condom use at most recent intercourse) was significantly predicted with more optimism about the future on a random probability sample of young adults in South Africa. This group of studies show how optimistic tendencies have different interactions with sexual behavior: Sometimes making it more likely for optimistic individuals to choose safe sex practices, and sometimes making individuals underestimate their risks of HIV infection.

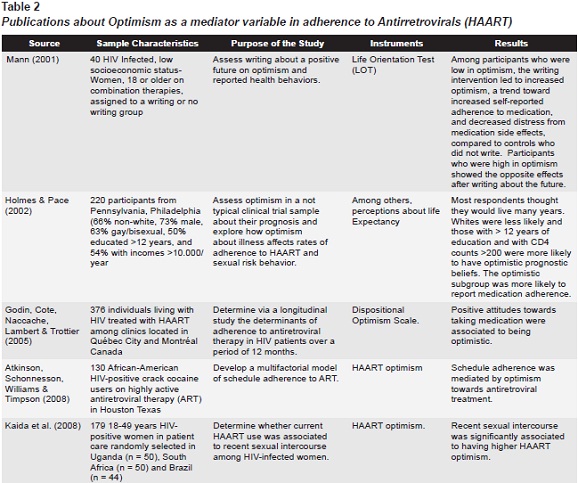

Optimism as a mediator variable in adherence to Antirretrovirals (ARV)

A total of 945 HIV Positive participants were included in the studies of this section. Studies incorporated a minimum of 40 and a maximum of 376 individuals. Three studies included men and women, and two included only women. Three studies were conducted in the United States, one was done in Canada and the last one was a three site based study: Uganda, Brazil and South Africa. All of them included quantitative measures.

The five studies showed associations between the optimistic tendency variable and Adherence to HAART; in one of them a writing intervention led to increased optimism and a trend towards greater adherence; another showed how optimistic prognostic beliefs were associated with medication adherence. Optimism towards HAART evaluated in three remaining studies, showed association with schedule adherence in one study, being optimistic on the second study, and associations between optimism towards HAART and recent sexual intercourse on the third one (Table 2). Optimism assessed in this group of studies showed positive effects toward health related behaviors, prognosis and ARV adherence determinants.

Summarizing, most of the studies in which Optimism was associated as a mediator variable of adherence to ARV showed a positive directionality. The more optimism showed by the participants, the more probable that patients behaviors toward adherence occurred (taking medication, adhering to the schedule). Other behaviors related with ARV adherence were also positively associated to optimism (positive attitudes toward taking medication).

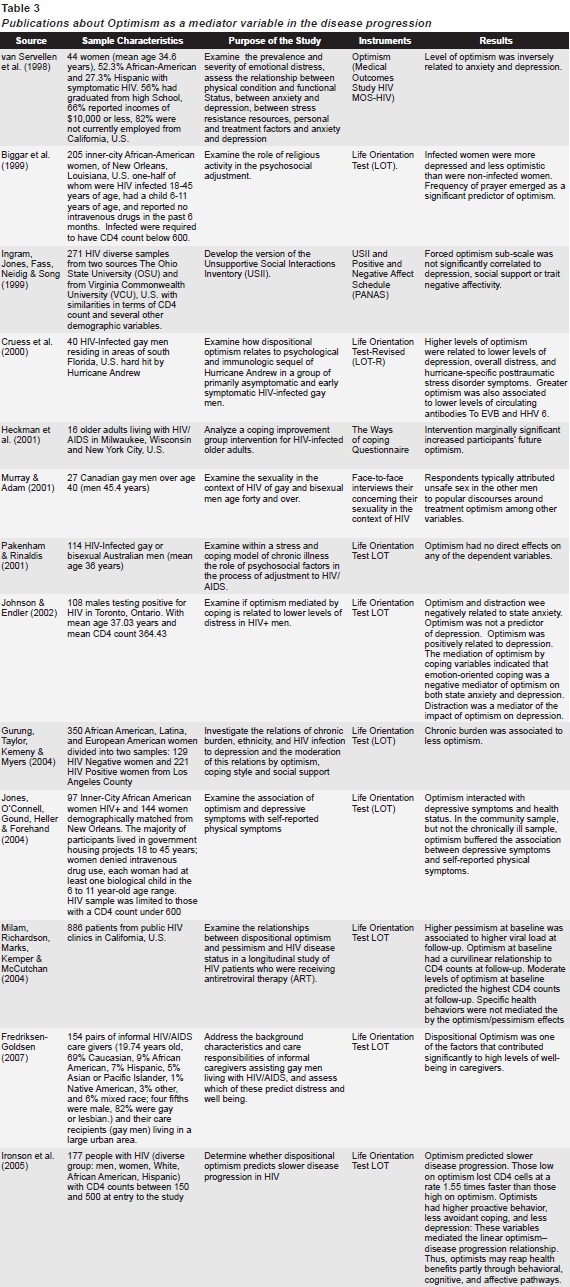

Optimism as a mediator variable in the disease progression

The studies related to optimism as a mediator variable in disease progression included more commonly US population (N = 11). Two of them were done in Canada, one in Australia and three studies did not mention the source of their samples. A total of 3.770 participants were included in these studies with a minimum of 16 and a maximum of 886.

In these groups of studies directionality in relationship between the Optimism Variable and the variable of interest was similar. Description of the comparable results between studies of this section is presented in Table 3.

Three studies found that Optimism had an inverse relation with Depression; one of them also found this direction regarding anxiety, and another found an inverse relation between optimism and distress and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) following a natural disaster. Another study found a negative relation between optimism and self reported symptoms. Two studies did not find connection between the optimistic tendency variable and the variable of interest. Two studies found that optimism was related to a more active coping, and negatively related to avoidant coping.

The other studies of this section found associations between optimism and other variables, some of them in a negative direction: Biggar et al (1999) found that being infected was associated with more depression and less optimism; Murray & Adam (2001) found that respondents attributed unsafe sex in other men to popular discourses around treatment optimism; Johnson & Endler (2002) found that optimism and distraction were negatively related to state anxiety; Ironson, Stuetzle & Fletcher (2006) observed that optimism was negatively related with active coping. In addition to the previously mentioned variables, optimism in participants was negatively related to: anxiety, depression, overall distress, hurricane-specific PTSD symptoms, lower levels of circulating antibodies (EVB and HHV 6), state anxiety, chronic burden, loosing CD4 cells faster, and avoidant coping.

A positive association was found between Optimism and resiliency, as well as with optimism and a change in spirituality/religion. Finally, optimism towards treatment was associated with more unsafe sex practices.

As we can see, optimism has a dynamic relationship with behaviors related to HIV infection, adherence to ARV and disease progression. Associated with the infection, optimism can lead to engagement with sexual risk behavior (UAIC, seeking sex partners online, no HIV testing); optimism toward treatment also works as a barrier for adolescents who then feel less susceptible to infection as well as perceive the disease less severe. Once infected, noting the positive side, optimism in PLHA is associated with depression, overall stress, state anxiety, and less self-reported symptoms, resiliency and higher proactive coping. However, when a person is infected with HIV, optimism can also be associated with unsafe sex (less condom use). Finally, talking about adherence and HAART optimism, the studies reviewed for this work showed a "positive effect" contributing to decrease distress from medication side effects, more adherence to schedules, and protected sex. Research should continue to be done to determine if optimism is always associated with healthy behaviors.

Results from this studies mentioned that Optimism predicted slower disease progression, prayer, highest CD4 counts (with lower levels of optimism), and well being in caregivers.

Only one study reported results regarding pessimism, and this variable showed a positive relationship with higher viral load. However, it is noteworthy that optimism and pessimism are not orthogonal, to be exact. Denollet & De Vries (2006) explain that negative mood may be separated in two affect dimensions, emotional exhaustion (deactivation) and anxious apprehension (activation); while positive affect, is associated with mental health, personal feelings of competence and greater satisfaction with social relationships.

Studies found that Optimism was predicted by frequency of prayer and being HIV infected Women.

DISCUSSION

From the 32 articles included in this review, 28 found a relationship between the optimistic tendency variable and the target behavior; in most cases the association was statistically significant. In this section we would like to discuss the results of these findings as well as answer the question: Is there really an "optimistic advantage" (Scheier & Carver, 1992) when talking about optimism and HIV related behaviors? Papers reviewed on optimism and HIV behaviors in this review are mainly associated with two topics: Optimism towards life outcomes and Optimism towards HIV treatments. The results suggest that these two "types" of Optimism have different effects on health behaviors.

Several studies included in this review related optimism as a mediator variable in sexual risk behavior, they illustrate a relationship between optimism towards treatment and more frequent health risk behaviors like UAIC, condom use at the most recent intercourse, internet-seeking partners and, in the particular case of women, engaging in high risk sexual behavior. Only two studies showed no relationship between HIV testing and treatment optimism, and another one reported no connection between condom use and HIV testing. The association between sexual risk behaviors and optimism toward treatments has been argued. Among others Huebner, Rebchook & Kegeles (2004) have raised the hypothesis that following risky encounters individuals increase their optimism about treatments and this happens more probably in men who feel susceptible to infection. The latter opposes to previous research (Cunningham & Thielemeir, 2001) which made opposite explanations, that is, optimism towards treatment lead to sexual risk behavior. These authors describe that in their research "one in two respondents agreed that people now are less worried about getting HIV than they used to be. And one in three agreed that because of new HIV treatments, HIV is no longer a life-threatening disease" (p. ii). So what needs to be explained is, whether optimism towards treatments antecedes risk behaviors making people perceive a low susceptibility and low HIV severity, or risk behaviors are followed by optimism concerning treatments. One possible explanation is given by Elford, Bolding, Maguire & Sherr (2000): "Optimism in the light of recent advances in HIV treatment may have triggered or have been used as a justification for sexual risk-taking" (p. 266).

Finally research should be done to find answers to the question raised by Biggar et al. (1999), regarding women: Are HIV women more depressed and less optimistic, and that contributes to risky practices? Or HIV turns women more depressed and less optimistic?

Some explanations to involvement in risky behaviors are pointed out by Holmes & Pace (2002) who talks about how an "overly enthusiastic" information environment helps people to make skewed self-perceptions about their risks, does this also applies to HIV Positive Women? Research should be done to clarify how optimism works in specific populations like young people or women, does it protect them from unsafe practices or does it buffers the optimism bias of the individual risks? Also, research could explain if optimism explains satisfactorily the complex social issues sexuality, of for example, young gay men (Lert, 2000).

On the other side, studies suggest that optimistic tendencies prepare the HIV patients to face the disease in a better way, prevent depression and anxiety, promote active coping styles, adherence, schedule adherence, slower disease progression, change in religiousness, resiliency, and higher CD4 counts (optimism in moderate levels).

In another vein, we would like to highlight the important aspect of taking into account what two studies draw attention to: "Optimal levels of optimism". Milam et al. (2004) details that there is a possibility that people who score high in optimism expect positive outcomes and are less likely to accomplish their aims or carry out health behaviors. Following this idea, moderate levels of optimism would seem more beneficial because a high level of optimism can end in taking risks, underestimating one's vulnerability towards disease, and even endangering someone else when already infected. Perhaps instruments that measure levels of optimism should be designed, and through them more effective interventions could be implemented. At this respect, in an article included in this review, Milam et al. (2004) found that a writing intervention had different effects in women's self-reported adherence to medication and distress from medication side effects; and the effect was associated with the level of optimism: In women with low optimism, the writing intervention led to increased optimism; in women with high optimism, the opposite effect was found. Maybe levels of optimism should even be inclusion criteria for interventions of this type.

We would like to recommend the use of biological indicators (Viral load, CD4 and CD8 counts) and its associations with optimism.

The inclusion of this data could provide more solid evidence to the hypothesis of optimism as a predicting variable of adherence, and disease progression.

We strongly agree with Aggleton (2001) who states that the challenge for future health promotion is related with the developing explanatory models that are more useful and that could help as a guide of whom actions could be taken to the still growing epidemic of HIV / AIDS.

The present study has several limitations, for example the access to the databases was restricted to the University's subscriptions and may have not included full-text access to studies related to Optimism and HIV related behaviors. This study also emphasized quantitative vs. qualitative research. Studies that included the term optimism not from a Positive Health perspective were left out. These preliminary conclusions highlight the need for a quantitative analysis that could provide further tools for researchers in the field that could help the decision-making process for the best evidence based interventions using Positive Psychology for people living with AIDS.

REFERENCES

Aggleton, P. (2001). HIV/AIDS in Europe: the challenge for health promotion research. Health Education Research, 16, 403-409. [ Links ]

Altman, L. (1981, July 3). Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals. The New York Times. [ Links ]

*Atkinson, J. S., Schonnesson, L. N., Williams, M. L. & Timpson, S. C. (2008). Associations among correlates of schedule adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a path analysis of a sample of crack cocaine using sexually active African-Americans with HIV infection. AIDS Care, 20, 253-262. [ Links ]

*Biggar, H., Forehand, R., Devine, D., Brody, G., Armistead, L., Morse, E., et al. (1999). Women who are HIV infected: the role of religious activity in psychosocial adjustment. AIDS Care, 11, 195-199. [ Links ]

Brennan, D. J., Welles, S. L., Miner, M. H., Ross, M. W. & Rosser, B.R. (2010). HIV treatment optimism and unsafe anal intercourse among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: findings from the positive connections study. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22, 126-137. [ Links ]

Carr, A. (2007). Psicología positiva. México: Paidós. [ Links ]

*Cotton, S., Puchalski, C. M., Sherman, S. N., Mrus, J. M., Peterman, A. H., Feinberg, J., et al. (2006). Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21 Suppl 5, S5-13. [ Links ]

*Cruess, S., Antoni, M., Kilbourn, K., Ironson, G., Klimas, N., Fletcher, M. A., et al. (2000). Optimism, distress, and immunologic status in HIV-infected gay men following Hurricane Andrew. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 7, 160-182. [ Links ]

Cunningham, J. K. & Thielemeir, M. A. (2001). Sexual Risk Behavior and HIV Treatment Optimism: HIV-Positive Persons at Ryan White CARE Act Providers in Orange County. Santa Ana, CA: Orange County Health Care Agency. [ Links ]

Denollet, J. & De Vries, J. (2006). Positive and negative affect within the realm of depression, stress and fatigue: The two-factor distress model of the Global Mood Scale (GMS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 91, 171-180. [ Links ]

Elford, J., Bolding, G., Maguire, M. & Sherr, L. (2000). Combination therapies for HIV and sexual risk behavior among gay men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficit Syndrome, 23, 266-271. [ Links ]

Folch, C., Casabona, J., Muñoz, R. & Zaragoza, K. (2005). Evolución de la prevalencia de infección por el VIH y de las conductas de riesgo en varones homo/bisexuales. Gaceta Sanitaria, 19, 294-301. [ Links ]

*Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I. (2007). HIV/AIDS caregiving: Predictors of well-being and distress. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 18, 53-73. [ Links ]

*Godin, G., Cote, J., Naccache, H., Lambert, L. D. & Trottier, S. (2005). Prediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a one-year longitudinal study. AIDS Care, 17, 493-504. [ Links ]

*Gurung, R. A. R., Taylor, S. E., Kemeny, M. & Myers, H. (2004). "HIV is not my biggest problem": The impact of HIV and chronic burden on depression in women at risk for AIDS. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 490-511. [ Links ]

*Hart, G. J., Williamson, L. M., Flowers, P., Frankis, J. S. & Der, G.J. (2002). Gay men's HIV testing behaviour in Scotland. AIDS Care, 14, 665-674. [ Links ]

*Heckman, T. G., Kochman, A., Sikkema, K. J., Kalichman, S. C., Masten, J., Bergholte, J., et al. (2001). A pilot coping improvement intervention for late middle-aged and older adults living with HIV/AIDS in the USA. AIDS Care, 13, 129-139. [ Links ]

*Hendriksen, E. S., Pettifor, A., Lee, S. J., Coates, T. J. & Rees, H.V. (2007). Predictors of condom use among young adults in South Africa: the Reproductive Health and HIV Research Unit National Youth Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1241-1248. [ Links ]

*Holmes, W. C. & Pace, J. L. (2002). HIV-seropositive individuals' optimistic beliefs about prognosis and relation to medication and safe sex adherence. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17, 677-683. [ Links ]

Huebner, D. M., Rebchook, G. M. & Kegeles, S. M. (2004). A longitudinal study of the association between treatment optimism and sexual risk behavior in young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 37, 1514-1519. [ Links ]

*Ijadunola, K. T., Abiona, T. C., Odu, O. O. & Ijadunola, M. Y. (2007). College students in Nigeria underestimate their risk of contracting HIV/AIDS infection. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 12, 131-137. [ Links ]

*Ingram, K. M., Jones, D. A., Fass, R. J., Neidig, J. L. & Song, Y. S. (1999). Social support and unsupportive social interactions: Their association with depression among people living with HIV. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/ HIV, 11, 313-329. [ Links ]

International Collaboration on HIV Optimism. (2003). HIV treatments optimism among gay men: an international perspective. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 32, 545-550. [ Links ]

*Ironson, G., Balbin, E., Stuetzle, R., Fletcher, M. A., O'Cleirigh, C., Laurenceau, J. P., et al. (2005). Dispositional optimism and the mechanisms by which it predicts slower disease progression in HIV: proactive behavior, avoidant coping, and depression. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12, 86-97. [ Links ]

*Ironson, G., Stuetzle, R. & Fletcher, M. A. (2006). An increase in religiousness/spirituality occurs after HIV diagnosis and predicts slower disease progression over 4 years in people with HIV. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21 Suppl 5, S62-68. [ Links ]

*Johnson, J. M. & Endler, N. S. (2002). Coping with human immunodeficiency virus: Do optimists fare better? Current Psychology, 21, 3-14. [ Links ]

*Jones, D. J., O'Connell, C., Gound, M., Heller, L. & Forehand, R. (2004). Predictors of self-reported physical symptoms in low income, inner-city african American women: The role of optimism, depressive symptoms, and chronic illness. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 112-121. [ Links ]

*Kaida, A., Gray, G., Bastos, F. I., Andia, I., Maier, M., McIntyre, J., et al. (2008). The relationship between HAART use and sexual activity among HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Brazil, South Africa, and Uganda. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 20, 21-25. [ Links ]

*Kalichman, S. C., Cherry, C., Cain, D., Pope, H. & Kalichman, M. (2005). Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of seeking sex partners on the internet among HIV-positive men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30, 243-250. [ Links ]

Lert, F. (2000). Advances in HIV treatment and prevention: should treatment optimism lead to prevention pessimism? AIDS Care, 12, 745-755. [ Links ]

*Mann, T. (2001). Effects of future writing and optimism on health behaviors in HIV-infected women. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 23, 26-33. [ Links ]

*Mao, L., Crawford, J., Van De Ven, P., Prestage, G., Grulich, A., Kaldor, J., et al. (2006). Differences between men who report frequent, occasional or no unprotected anal intercourse with casual partners among a cohort of HIV-seronegative gay men in Sydney, Australia. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 18, 942-945. [ Links ]

*Milam, J. E., Richardson, J. L., Marks, G., Kemper, C. A. & McCutchan, A. J. (2004). The roles of dispositional optimism and pessimism in HIV disease progression. Psychology and Health, 19, 167-181. [ Links ]

*Murray, J. & Adam, B. D. (2001). Aging, sexuality, and HIV issues among older gay men. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 10, 75-90. [ Links ]

*Pakenham, K. I. & Rinaldis, M. (2001). The role of illness, resources, appraisal, and coping strategies in adjustment to HIV/AIDS: the direct and buffering effects. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 259-279. [ Links ]

Rasmussen, H. N., Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F. & Carver, C. S. (2006). Self-regulation processes and health: the importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Journal of Personality, 74, 1721-1747. [ Links ]

*Rawstorne, P., Fogarty, A., Crawford, J., Prestage, G., Grierson, J., Grulich, A., et al. (2007). Differences between HIV-positive gay men who 'frequently', 'sometimes' or 'never' engage in unprotected anal intercourse with serononconcordant casual partners: positive Health cohort, Australia. AIDS Care, 19, 514-522. [ Links ]

*Rogers, M. E., Hansen, N. B., Levy, B. R., Tate, D. C. & Sikkema, K. J. (2005). Optimism and coping with loss in bereaved HIV-infected men and women. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 341-360. [ Links ]

Scheier, M. F. & Carver, C. S. (1992). Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 228. [ Links ]

*Segerstrom, S. C. (2005). Optimism and immunity: Do positive thoughts always lead to positive effects? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 19, 195-200. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P. (2008). Positive health. Applied Psychology, 57(SUPPL. 1), 18. [ Links ]

Sherr, L., Lampe, F., Norwood, S., Leake Date, H., Harding, R., Johnson, M., et al. (2008). Adherence to antiretroviral treatment in patients with HIV in the UK: a study of complexity. AIDS Care, 20, 442-448. [ Links ]

*Somlai, A. M., Kelly, J. A., Heckman, T. G., Hackl, K., Runge, L. & Wright, C. (2000). Life optimism, substance use, and AIDS specific attitudes associated with HIV risk behavior among disadvantaged inner-city women. Journal of Women's Health and Gender-Based Medicine, 9, 1101-1111. [ Links ]

*Tarakeshwar, N., Hansen, N. B., Kochman, A., Fox, A. & Sikkema, K. J. (2006). Resiliency among individuals with childhood sexual abuse and HIV: Perspectives on addressing sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19, 449-460. [ Links ]

Taylor, S. E. & Armor, D. A. (1996). Positive Illusions and Coping with Adversity. Journal of Personality, 64, 873-898. [ Links ]

*Tillotson, J. & Maharaj, P. (2001). Barriers to HIV/AIDS protective Behavior among African adolescent males in townships secondary schools in Durban. Society in Transition, 32, 83-100. [ Links ]

Tsevat, J., Leonard, A. C., Szaflarski, M., Sherman, S. N., Cotton, S., Mrus, J. M., et al. (2009). Change in quality of life after being diagnosed with HIV: a multicenter longitudinal study. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 23, 931-937. [ Links ]

*Van de Ven, P., Crawford, J., Kippax, S., Knox, S. & Prestage, G. (2000). A scale of optimism-scepticism in the context of HIV treatments. AIDS Care, 12, 171-176. [ Links ]

*van Servellen, G., Sarna, L., Nyamathi, A., Padilla, G., Brecht, M. L. & Jablonski, K. J. (1998). Emotional distress in women with symptomatic HIV disease. Issues on Mental Health Nursing, 19, 173-188. [ Links ]

*Zak-Place, J. & Stern, M. (2004). Health belief factors and dispositional optimism as predictors of STD and HIV preventive behavior. Journal of American College Health, 52, 229-236. [ Links ]

*References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the tables.