Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Análisis Político

versão impressa ISSN 0121-4705

anal.polit. v.22 n.65 Bogotá jan./abr. 2009

Plan Colombia: Exploring Some Myths And Effects On Colombian Foreign Policy 1998-2006

Plan Colombia: Explorando Algunos Mitos Y Efectos Sobre Política Exterior Colombiana 1998-2006

Rocío Pachón

Professor in the Departments of Political Science and International Relations of the University

of Rosario in Bogotá-Colombia. Professional in International Relations and Specialist in European Studies of the same University. MSc in Latin American Studies of University of Oxford.

SUMMARY

The internationalization of Colombian conflict with the setting up of Plan Colombia by Andrés Pastrana, then maintained by Álvaro Uribe, increased foreign policy fragmentation and confusion in the conduct of the country's foreign relations. Three arguments are analyzed: first, Plan Colombia intensified the presidential conduct of diplomatic relations and the fragmentation of foreign relations, and made the role of the Foreign Ministry weaker than before. Second, Plan Colombia made relations with USA more complex and diminished and to some extent worsened Colombia's relations with the European Union and most of its members. And finally, Plan Colombia stimulated the international participation of non-state actors, especially non-government organizations, who started to do a parallel diplomacy in Washington and in Brussels. The presidency of Andrés Pastrana and the first presidency of Álvaro Uribe will be examined within the geographic triangle of Colombia, the USA and Europe.

Key words: Plan Colombia, foreign policy.

RESUMEN

La internacionalización del conflicto colombiano y la implementación del Plan Colombia, ambos sucesos instaurados por el gobierno del presidente Andrés Pastrana, y posteriormente, seguidos por la administración del presidente Álvaro uribe incrementó el problema de la fragmentación de la política exterior y la confusión para conducir las relaciones exteriores del país. Tres argumentos son analizados: primero, el Plan Colombia intensificó la conducta presidencialista en las relaciones diplomáticas y la fragmentación de la política exterior, e hizo el rol del Ministerio de Relaciones más débil que antes. Segundo, el Plan Colombia hizo más complejas las relaciones con Estados Unidos y de alguna manera empeoro las relaciones del país con la Unión Europea y algunos de sus Estados miembros. Y finalmente, el Plan Colombia estimuló la participación internacional de los actores no estatales, especialmente las organizaciones no gubernamentales quienes empezaron a desarrollar una diplomacia paralela en Washington y en Bruselas. La presidencia de Andrés Pastrana y el primer mandato del presidente Álvaro Uribe son examinados en el marco del triángulo de Colombia, Estados Unidos y Europa.

Palabras clave: Plan Colombia, política exterior.

INTRODUCTION

Foreign policies, in general, face the challenge of adapting themselves to the changes brought by the new international circumstance of interdependence and globalization (1). One such change has undoubtedly been the appearance of new sub-regional, national and supranational actors. Many aspects have become more confused and complicated: the role of the nation-states, and who within the state is responsible for foreign policy.

Colombian foreign affairs are not an exception to this. The role of the Foreign Ministry has been reduced, and its tasks are now shared with other ministries, government agencies and particular actors: the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Defense, and other institutions, actors and non-government organizations (2). The internationalization of Colombian conflict with the setting up of Plan Colombia by Andrés Pastrana (1998 - 2002), maintained by Álvaro Uribe (2002 - 2006, 2006 - 2010), increased foreign policy fragmentation and confusion in the conduct of the country's foreign relations.

Contemporary reflections on this field have done little to solve these problems. Academic analyses have spoken of the weaknesses of Colombian foreign policies, the internationalization of Colombian problems, of the "negative insertion" of the country overseas, and of the projection of a feeble image of the Colombian government. Some studies have analyzed the effects of the domestic conflict, the drugs problem and, more recently, problems related to terrorism. Others have begun the study of the design of national foreign policy, the weaknesses in the structure of the Foreign Ministry, and the defects in the formation of diplomatic representatives.

Few analyses have focused on the problem of the coexistence of a weak and fragmented capacity for formulating and executing foreign policy and an international context which involves multiple actors and particular concerns other than those of the State. The guiding question this essay will attend is as follows: to what extent have the internationalization of the conflict and the development of Plan Colombia affected national foreign policy and increased the problem of making and carrying through a coherent foreign policy? The presidency of Andrés Pastrana and the first presidency of Álvaro Uribe will be examined within the geographic triangle of Colombia, the USA and Europe.

The approach to the question will be guided by three hypotheses: the first hypothesis is that the development of Plan Colombia intensified the presidential conduct of diplomatic relations and the fragmentation of foreign relations, and made the role of the Foreign Ministry weaker than before. It will be shown that the design of Plan Colombia, first in Colombia and then in Washington, was directly and exclusively managed by President Pastrana and his team. The implementation of Plan Colombia, under Pastrana and Uribe, has subsequently come under the Ministry of Defense, the International Cooperation Agency (ICA), and the Agency for Social Action (Acción Social) (3).

The second hypothesis is that Plan Colombia was the key to restoring relations with the USA, but made these relations more complex, and at the same time diminished and to some extent worsened Colombia's relations with the European Union and most of its members. To support this hypothesis the essay will show that, although relations with the White House, the Department of State, the Department of Justice and others government agencies were restored, the importance of relations with other actors increased, as was the case with the Pentagon-Southern Command-, the National Security Board (NSB), the Anti-drug Tsar and the Congress. Plan Colombia multiplied relations with numerous agencies and came to be a visible political issue, hence dependent to a degree on Congress and on the electoral outcomes of U.S. politics.

Finally, the third hypothesis is that Plan Colombia stimulated the international participation of non-state actors, especially non-government organizations, particularly the defenders of human rights, whose actions sought to influence the conduct of foreign governments and multilateral organizations towards Colombia. Colombia's foreign relations came to be affected not only by the effects of fragmentation and the unbalanced nature of relations with Washington, with Brussels and with individual European governments, but also by the international action of these non-governmental agents.

It is difficult to find a theoretical framework applicable to this scene. Most theories have not focused on the analysis of the foreign affairs of weaker countries and the relationships between these countries and conflict dynamics (4). Neorealist studies focus on the role of powerful countries and they assume that domestic contexts have a limited effect on foreign policies. Among these theories, it is "liberal realism" which best fits the present study, for it involves both internal and external aspects and it is not sensible to privilege one side over the other, as well as that of "peripheral realism", which provides a coherent explanation for the majority of conflicts in the international system in tracing their origins, "state making" and "state breaking" and "state failure" problems, and the internal and external pressure operating in the Third World which create a fertile field for domestic and interstate conflict between countries.

The neoinstitutionalist approach, on its side, although it takes into account the development of domestic rules and structures, does not view them in the context of conflict dynamics. The existing literature on the foreign policies of small states, developing countries and middle power countries, perhaps the most useful for this study, is also limited in the analysis of the variable "conflict". To fulfill that theoretical space, this investigation use different sources as Colombian government documents, academic publications, the press, NGO's publications, direct interviews and those of Colombian and American "think thanks".

PRESIDENTIAL DIPLOMACY AND THE FRAGMENTATION OF FOREIGN POLICY

The development of Plan Colombia intensified presidential diplomacy, the fragmentation of Colombian Foreign Affairs, and made the role of the Foreign Relations Ministry even weaker. In fact, the process of launching Plan Colombia, first in Bogotá and then in Washington, was managed "by the administration entirely, without the participation of the Congress, other political actors, or civil society" (5). The Plan's implementation under Pastrana's government, and its continuation during Uribe's first mandate was, carried out by the Ministry of Defense and the International Cooperation Agency, which later became Social Action (Acción Social). The Foreign Ministry came to be to a great extent also excluded from the management of the most important elements in the international relations of the country during these two presidential terms as the negotiations for the renewal of "Ley para la Erradicación de Drogas y Promoción del Comercio Andino" (ATPA), and the dialogue on the creation of Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas (ALCA), and from 2000 on, the central element in Colombia's relations with the United States (6).

To understand the effects of Plan Colombia on the fragmentation of the Colombian foreign policy, here it is analyzed the closed process favored by the Colombian government in elaborating and formulating it.

A COMPREHENSIVE PLAN MARSHALL/COLOMBIA FOR PEACE, DEVELOPMENT AND STABILITY IN COLOMBIA.

Plan Colombia (7), together with the later process of formulating in detail the aid for Colombia that would receive the backing of the administration and Congress of the United States, was an initiative of President Pastrana and his team. In fact, this strategy emerged as an electoral pledge between the first round and the run-off of the 1998 presidential campaign. It combined a negative diagnosis of the internal situation in Colombia with a positive, though naïve, perspective of a cooperating world.

The original idea of a "Plan Marshall" for Colombia was elaborated into a strategy for peace and an instrument for gaining cooperation from the international community, for restoring good relations with the U.S. and for diversifying international relations at the same time.

Pastrana had early included making peace as an essential point in his platform. It was necessary to provide a fresh concept, combining new and previous strategies, purposes and principles (8). Thus, with his negative vision of a country immersed in the deepest political, economic, security, social and drugs crisis and his view of a positive world, more inclined toward cooperation, he and his team considered that the solution was to appeal to the international community for support for a plan for integral peace, tackling such causes of conflict as poverty, rather than solely confronting insurgent groups in a military way. This did not imply overlooking the need for strengthening the security forces and combating violent groups, which was also priority for his government (9).

Pastrana considered that the idea of a military solution had failed in the past, and rejected this option, asserting that he did not just seek a political negotiation with the guerrillas, but a plan for international cooperation, such as Marshall had devised for Europe. It was an ambitious and over-optimistic proposal, as Colombian conditions were far different from those in Europe at the end of World War II. Nonetheless, it was an imaginative move to overcome Colombia's isolation and to seek help to face the country's multiple crises (10).

Thus, the original idea for the "Plan Marshall" for Colombia was inserted into a more comprehensive strategy for peace and development, outlined in his statement one week after he had narrowly lost the first electoral round of 8 March 1998. Pastrana argued that "[Drug crops are] a social problem whose solution must be itself part of the solution to the armed conflict. Developed countries should help us to implement some sort of "Marshall Plan" for Colombia, which will allow us to make great investments in the social field, to offer our peasants alternatives to illicit crops"(11).

Once Pastrana was elected president, the idea of a Plan Marshall was included in the "Plan Nacional de Desarrollo" as Plan Colombia (12). The aim was to restore relations with the United States and also to improve relations with Europe, Latin American neighbours and the multilateral organizations (13).

In this first phase, the integral plan was not discussed outside the president's close team and the delegated writers. The earliest version was written in December 1998 by Rodrigo Guerrero, former Mayor of Cali, who had extensive experience in social projects. It was launched in Puerto Wilches, Santander, on 19 December as "un conjunto de proyectos de inversiones estratégicas para la paz, que canalizara los esfuerzos compatriotas a favor de quienes viven en las zonas mas afectadas por la violencia" (14). Guerrero was later replaced by Jaime Ruiz Llano and Mauricio Cardenas, the authors of the formal document presented in 1999 to the international community.

It is no secret that the emphasis of Plan Colombia was changed from an integral social aid programme to an antinarcotics strategy after the summer of 1999 (15). This change was the result of U.S. government concerns. The Colombian side of the negotiation was managed by the presidential team. Plan Colombia's formulation did not include any representation of the National Congress or other governmental entities, though it did incorporate concerns of the Ministry of Defense (16). Here it is important, however, to understand that few governments involve congressmen in the formulation of their foreign policy, and few presidents or heads of government are content to leave foreign affairs to foreign ministers. The particular fault of Colombia was the weakness of the Foreign Ministry in so many areas of the conduct of foreign policy.

FRAGMENTATION OF THE COLOMBIAN FOREIGN POLICY

The negotiation of Plan Colombia and its implementation, introduced yet further division in Colombia's conduct of its foreign policy. The importance in the development of the Plan of many other government institutions and the relevance acquired of non-government actors intensified the weaknesses of the Foreign Ministry. The proliferation of American agencies now interested in the Colombian case was the counterpart of this (17).

In Colombia, the militar components of Plan Colombia were coordinated and executed from the Presidency, together with "la Alta Conserjería para la Paz, el Ministerio de Defensa, y la Dirección de la Policía Nacional". Social components, on its side, were coordinated and executed from the Peace Investment Fund (PIF) (18) and later, from 2005 on, from the Presidential Agency for Social Action and International Cooperation (19).

The results of the implementation of the Plan had to be evaluated internationally. Therefore the Plan's executors became the new diplomatic agents of the country. The presidential diplomacy of Andres Pastrana and Álvaro Uribe was accompanied by the Alto Consejero para la Paz, the Minister of Defense, the National Police Director and the Director of Social Action, the new companions of the President during his visits to Washington and Europe. Other Ministers might also take part, according to the agenda.

The role of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Guillermo Fernández de Soto under Pastrana and Carolina Barco under Uribe, was reduced. Luis Alberto Moreno, the Colombian Ambassador in Washington, was the representative for the management of Plan Colombia's affairs in United States. His exceptional access to the White House gave him great importance in the relationship between Colombia and Washington during the two governments that are being studied here.

The lack of coordination in Washington's policies towards Colombia undoubtedly also had an impact on the conduct of foreign relations in Colombia.

Southern Command and the Military Group of the American Embassy in Bogotá, both of them under to the Pentagon, were the agencies that were most strengthened (20). This fact accounts for the increased importance of the Colombian Ministry of Defense and the Military Forces in their relations with the United States. Otto Reich, ex-under secretary for Hemispheric Affairs, and who had been involved with relations with Latin America since Ronald Reagan's times, did not have a significant role in Washington's policy towards Colombia. Though he was nominated for the Department of State's highest post in Latin American affairs, he did not obtain approval by Congress. Ambassador Roger Noriega, who had been appointed adjunct Secretary of State for Western Hemispheric Affairs, in July 2003, was also remembered as having had little influence. In general, for the Secretary of State conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran, and other "evil axis" actors came to attract Washington's attention more than the situation in Colombia (21).

The diversification of American agents in the management of Plan Colombia in Washington demanded similar diversity on the part of Colombian officials. Not only was the focus of the relationship now firmly in Washington; it also had to face the vicissitudes generated by the ever more complicated agendas.

PLAN COLOMBIA: BOGOTÁ AND WASHINGTON AND BOGOTÁ AND EUROPE

Plan Colombia brought a more complex relation between Bogotá and Washington and affected Colombia's relations with the European Union and its member states. Regarding the US it was building up a complex framework of relationships.The U.S. Foreign Policy changed and also the dynamics of its relations with Colombia (22). The White House, the Department of State, the Department of Justice, and other government agencies all came to exercise formulation and execution tasks. The Pentagon and South Command, the Board of National Security (BNS), the anti-drugs Czar and the Congress become strategic and active actors for the US-Colombia relations.

New relations with traditional US actors

For the White House,the approval of Plan Colombia was an important matter. As was mentioned above, during President Clinton's government the impulse given to this Plan after the summer 1999 was considered a strategic and necessary decision. President Bush confirmed support on the Plan Colombia, and more strategy after the terrorist attack on 11 September 2001.

Now part of the international war on terrorism, Plan Colombia was seen not only as an instrument to fight drugs but also as the way to combat terrorism in Colombia. President Bush reaffirmed support on anti-drugs fight and to Plan Colombia, and he would later recognize the achievements of President Alvaro Uribe's Democratic Security Policy. In 2004 he announced that he would request Congress to renew support for Plan Colombia (23).

Although the Department of State is a part of the Executive Branch along with the White House, the two tend to perform separately. The Department of State is a second actor and must be understood as "a bureaucracy apart, with closer contact to the Congress, while the White House team serves the political needs of the President"(24).

As regards Plan Colombia, this institution was the authority which drew up the list of foreign terrorist organizations, to which the FARC, ELN and the AUC of Colombia belong. The Department's reports approved what was being done in Colombia. This can be confirmed in their International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, March 2004. Madeleine Albright, Collen Powell and Condoleezza Rice were the secretaries of state concerned. The Sub-secretary of State, Thomas Pickering, during Albright's period, played an important role, as well (25).

Madeleine Albright (1997-2002) prioritized relations with Hong Kong, China, Kenya, Tanzania, Iraq, and in 2000 with North Korea, when she paid an official visit to that country. Colombia, however, also had some prominence. With Albright and Thomas Pickering, who had been assigned to promote Plan Colombia in Bogotá and in the Congress of the United States, the Department of State became one of the most important institutions to support Plan Colombia.

Collen Powell was also in favor of supporting Plan Colombia. As Secretary of State at 11 September 2001, he was in Lime and made some pronouncements at that time on FARC and AUC. Nonetheless, he had to face criticisms of Plan Colombia's effectiveness from some American congressmen and he admitted that much more had to be done in order to reduce the high demand for drugs and to improve respect for human rights.

Condoleezza Rice was a faithful defender of Plan Colombia, during the period analyzed in this essay. Under her, the international priorities for the United States were focused on the Middle East and on relations with Russia. In the Western Hemisphere, however, Colombia had an important priority status. Even when Plan Colombia's five-year term came to an end in 2006, for Rice, the commitment to Colombia was not over (26).

The Department of Justiceplays a prominent part in the international strategy of Washington against narcotics, since the Department includes the DEA in its organization. The DEA is in charge of the coordination of all repressive efforts against narco-traffic, and it has numerous agents in Colombia (27). The strengthening of the DEA's action in Colombia can be seen from 2003 onwards: the DEA and the Ministry of Defense committed themselves to make the expropriation of assets more rigorous and transparent (28).

Even Plan Colombia increased the role of these three American agencies in relations with Colombia, other actors, however, strengthened their role as well.

The increased role of other US agencies

Southern Command became more involved. This was made clear by the presence of an expanded military group in the American Embassy in Colombia, which started to fulfill a number of missions and responsibilities. After 11 September 2001 U.S. military aid to Colombia ceased to be restrictive to counter-narcotics operations.

Although the Board of National Security (BNS) re-designed Colombia's strategy from 2001 on, the U.S. also acquired new priorities in the Middle East and against other enemies announced under Bush government according to the National Security Strategy of 2002. However, the United States let the world see the importance still assigned to Colombia. The document stated that "in the Western Hemisphere we have formed flexible coalitions with countries that share our priorities, particularly Mexico, Brazil, Canada, Chile, and Colombia" (29). The two paragraphs which concerned the Western Hemisphere were devoted to Colombia and the Andean Community.

The National Security Strategy was the document in which Washington clarified the idea of developing an active strategy to help the Andean nations in economic and judicial matters, and, in their fight against terrorist organizations. It was in this document that the United States recognized the link between the war on terrorism and the extremist groups in Colombia.

The Anti-drug Czar, General Barry McCaffrey, who held office until 2001, took an active and sometimes controversial part. John Walters's performance was, different. For the former, American action in the fight against drugs should be in Colombia, not in the U.S. The main goal of such action should be focused on attacking cocaine and poppy crops. His activism in Colombia was on some occasions exaggerated (30).

Walters played a role marked by contradictions and a growing general questioning. "Durante su periodo, incluyendo datos oficiales e independientes, el área de cultivo de la hoja de coca se expandió de tres departamentos a casi todo el territorio colombiano. (...) En abril de 2001, el mismo zar antidrogas reconoció que en el último año el cultivo había aumentado en cerca de un 30%"(31).

The importance of the office, created in 1988, increased with the implementation of Plan Colombia. The anti-drugs Czar came to be one of the most important of the President's advisers on relations with Colombia. He "advises the President regarding changes in the organization, management, budgeting, and personnel of Federal Agencies that could affect the Nation's anti-drug efforts; and regarding Federal agency compliance with their obligations under the Strategy"(32).

Finally, among the institutions which increased their degree of participation in relations with Colombia from 1998, was the Congress of the United States. Congress's role in budget appropriations gave it great influence from the start: financial approval for Plan Colombia depended on Congress. Once Thomas Pickering and the Colombian Ambassador Luis Alberto Moreno and their respective teams had agreed the find version of Plan Colombia, they sought financial support from Congress, not only for one year but for a three-year term.

Plan Colombia and its continuous renewals thus became the subject not only of debate in Congress, between Republicans and Democrats, but also to the differences between the Legislative and Executive. During the times that the leading party in Congress was not that of the President, as in December 1999 and the following months, Plan Colombia faced difficulties for its approval.

Later on, with the Republicans controlling Congress and with a Republican President, the leader of the House of Representative, J. Dennis Hastert, emerged on "a solid leader in the creation of a bipartisan consensus in the Congress of the United States for the assistance of that country to Colombia." (33) During this period, the bipartisan consensus was shown with Robert Menéndez's declaration: a renown Democrat and critic of the Plan, he said that it was necessary to maintain the goals achieved in the Andean Regional Initiative, and stressed the opportunity to "permanently interrupt all drug dealers' moves, as well as to improve security, stability, respect for human rights and real opportunities for Colombia"(34).

The importance in U.S politics of the drug issue, and its relation with the internal conflict in Colombia, enabled Pastrana to re-establish good relations with Washington. Plan Colombia was instrument and the result. Although this diplomacy worked well with the United States, it unfortunately failed to achieve the same success with the European Union and most of its member states.

In fact, the support given to Plan Colombia in Washington after August 1999 affected the relationships between Colombia and many European states. First, it produced a negative response on the part of many Europeans, who viewed the Plan as excessively centered on drugs and coca eradication. Only Spain and England showed some support for it. Secondly, especially after the ending of Pastrana's peace process in February 2002, it appeared to reduce the importance of Europe's role in Colombia. Their participation in Colombia was reduced to a barely developed and vague policy of cooperation.

With European Union a negative view was emphasize so as proposals for alternative strategies

The European Parliament in its statement about Plan Colombia in February 2001 rejected Plan Colombia. It takes the view that, in addition to their military dimension, the prevailing situation and conflict in Colombia have a social and political dimension whose roots lie in economic, political, cultural and social exclusion. For that it believes that stepping up military involvement in the fight against drugs involves the risk of sparking off an escalation of the conflict in the region, and that military solutions cannot bring about lasting peace. Additionally, stresses that "European Union action should pursue its own, non-military strategy combining neutrality, transparency, the participation of civil society and undertakings from the parties involved in the negotiations"(35).

Several factors account for this negative reaction. From the European perspective, the Plan did not emphasize enough peace-making and social justice. Additionally, the Europeans were naturally indifferent to the military dimension, despite its obvious importance to the U.S.

This decision of the Parliament affected bilateral relations. They went through a period of confusion and instability, before this was revoked with some Europeans participation in Pastrana's peace process, and a moderate programme of assistance.

Despite this cooperation policy, Colombia was hardly important to the EU and the EU was not the most important donor to Colombia. West Balkans, Central and East Europe, the Mediterranean countries, Middle East, the African, Caribbean and Pacific countries were over any Latin American countries.

During 2000-2006, the Assistance for Reconstruction, Development and Stabilisation (CARDS) allocated to Albania amounted to EUR 282.1 million (36) and for Bosnia and Herzegovina amounted EUR 502.8 million (37). EC aid to Colombia amounted up to EUR 105 million. This assistance consisted in Humanitarian aid, Human Rights protection, NGO projects, environmental projects, the fight against AIDS, specific action against land mines, decentralized cooperation, rapid reaction mechanism projects and migration issues (38).

United States through USAID was far the largest donors. European Union, taking together the Commission's amount allocated to Colombia and that of each European country, was the second donor (39).

There was much confusion in the statistical data on EU cooperation to Colombia. Planeación Nacional, the International Cooperation Agency, the Commission Delegation for Colombia and Ecuador and the individual European country's agencies for cooperation with Colombia give different statistical results.

This confusing scene, give the EU some visibility. In Colombia and overseas, the Europeans sought to show their altruistic profile, demonstrated their actions in this distant country. This was part of the EU's search to find an identity, as a cooperative actor, different from the US.

Europe: a second rank actor in Colombia once again.

Despite President Pastrana's stated hopes, Plan Colombia had met with a disappointing response in the EU and most of its member states.

At first, it was naively thought that Europe might balance US military support and American influence in Colombia, with an emphasis on development and social aid. Such thought showed, from the start, the slight knowledge that the Colombian government had about the European Union. Europe was then composed of sixteen members, fifteen states and a supranational structure, all of them holding different initiatives and interests.

Relations between Colombia and Europe, can also be studied in the light of two other factors. The first of these was the change applied in the Colombian Foreign Ministry structure in 2000, under Guillermo Fernández de Soto (40). This lowered the degree of priority of certain important regions, and this was the case of Europe. The second factor was some mistaken decisions made by the Colombian government which, whether though ignorance or lack of interest damaged relations with Europe.

The changes in the Ministry structure in 2000 lowered the level of importance given to the relations between Colombia and Europe. The new structure altered the balance in the foreign ministry which in 1992 had placed the United States, Europe, Asia, and Africa, Vice-Ministers. A reform re-structured the Ministry into two main divisions, bilateral and multilateral relations. With the removal of the Vice-Ministry for European affairs and, later on, of the General Direction for Europe, Europe was brought down from second to fourth place in the level of priorities in Colombia's foreign policy (41). This situation was worsened by further changes introduced in 2002 under President Uribe. The influence of Ministry of Defense in Colombian foreign affairs was a new factor that had the effect of lessening interest in most of Europe.

Through ignorance about or lack of interest in Europe, Presidents Pastrana and Uribe clearly made some mistakes. Focused on domestic and security matters, the Uribe government paid no sufficient attention to Europe.

An outstanding example was the decision made to close for reasons of economy the Colombian embassies in Denmark and Greece during the second half of 2002. The Colombian government was not aware that Denmark was to be President of the EU during that term, and that Greece, apart from being Denmark's successor, was the country in charge of the revision of the Generalized Preference System GPS-drugs, granted to the ACN (Andean Community of Nations) for their products in the European market (42).

President Uribe's first tour of Europe, in February 2004 was not as successful as it might have been. Even though his performance in Brussels can be considered positive - he presented his Democratic Security Policy and set out its results and the country's economic recovery - his visit to the European Parliament should have been omitted. Uribe found generous interlocutors in Javier Solana, High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Common Security, as well as in Chris Patten, Commissioner for Foreign Affairs. He also had a bilateral encounter with Gerard Schröeder who approved EUR 14 million for Colombia for the following two years. But in his visit to the European Parliament, he met with opposition from members of Social Democrat parties and ONG representatives, who greeted him with street demonstrations.

The general weaknesses of Colombian diplomacy in Europe came from defects in the formulation of Colombian foreign policy, inadequately staffed embassies, frequent changes of Ambassador, countries where Colombia has no representation, ignorance of the effects of the expansion the of number of countries in the European Union and lack of Colombian representation in those countries, inadequate coordination between Colombian ministries and agencies in charge of relations with Europe, lack of skill in relation with NGOs, weak coordination of European policy with other Latin American nations, weak coordination between Colombian policy towards Europe and towards the US. The firs of weaknesses could be made longer. Colombia is also unaware of the diplomatic resources of enemies and rivals, for example of the resources of President Hugo Chavez.

COLOMBIA AND NON-GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATIONS

In Colombia a vibrant national and international civil society - NGOs and international community- was engaged in a search for peace from 1998. It became more prominent with the internationalization of the conflict and the implementation of Plan Colombia. Although, the aim of most writings has been on "evaluating the effects of the internal armed conflict on Colombian civil society and the consolidation of democratic institutions, to examine civil society initiatives that could contribute to the resolution of the conflict, and to explore ways that the international community might support peace efforts in Colombia" (43), what is important here is to understand that the external lobbying by NGOs created a parallel diplomacy which affected the image of the country and of the government internationally, and posed an additional problem for Colombian foreign relations (44).

As a middle level developing country, Colombia would have attracted little NGO attention had it not been for the intensity conflict. The Colombian government's claim for cooperation was the armed conflict situation. With the request for aid and cooperation the role of national and international NGOs became more significant. Light was shed around the world on the humanitarian crisis and the human rights situation in Colombia.

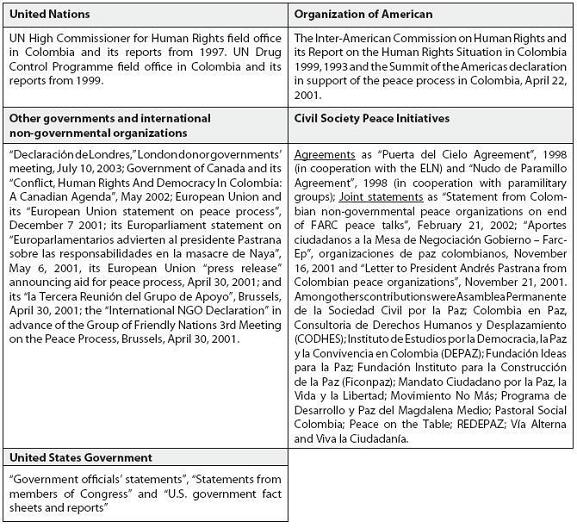

It is a complex task to measure the impact of NGOs, other civil society actors and in general, the international community, particularly their capacity to influence other countries' and agencies' decision-making in their relations with Colombia. However, this section will study the actions of the human rights NGOs. In figure 1 we can see the large number of actions from civil society and international community.

The effects of a parallel diplomacy

Civil society has used multiple methods to express its rejection of violence and to contribute to peace-building. It can be argued that the principal motivation for social mobilization in Colombia in the 1990s was the rejection of violence and support for the search for peace. Nevertheless, with internationalization of Colombian conflict and implementation of Plan Colombia many of those focused on the defense and protection of human rights, intensified and made more efficient their diplomacy parallel to that of the Colombian government. It was few in the Andrés Pastrana's Government as the dynamics of the process with the guerrillas had a significant impact on the dynamics of the peace organizations at a national level, given that these organizations focused their attention on what was happening in the negotiations between the government and the FARC, but huge in the Alvaro Uribe's first mandate, because with the end of the peace process, those NGOs entered into a period of crisis and flux so found in the conflict's internationalization and the implementation of Plan Colombia between Bogotá and Washington the field for their functioning abroad.

The parallel diplomacy of the NGOs during the governments of Andrés Pastrana and more intensified, during of the Álvaro Uribe affected Colombian foreign relations in three ways. They affected the international image of Colombia and created confusion as regards the country's internal problems. They undermined the role of the government overseas, before some of the United Nations organizations, the European Union, some specific member states, other international agencies and sectors of American government and society. Finally, Colombian and international NGOs managed to introduce themselves, with recognized rights, into the decision-making process and into the agenda of cooperation established at the European "mesa de donantes".

Deterioration of the image of Colombia and its government

In general Colombians and non Colombians NGOs' networking provides the benefit, of course, of information sharing and increased access to expertise. There is also the inspirational value from knowing that the struggle to protect human rights is not a solitary one. Moreover, those networks and alliances provide protection to organizations and individuals struggling in repressive environments. However, the parallel diplomacy used by those Colombian and non Colombian human rights NGOs to strengthen their instruments of influence in the diplomatic field also affected the international image of the country and created confusion about its internal realities.

Most of their work consisted of showing the rough, brutal and inhumane side of the Colombian conflict. This affected the strategy shared by the two governments - Pastrana's and Uribe's - of making the internal conflict an international issue, showing first the progress obtained in the peace process and, later, the achievements in the matter of security and the economic growth. The intention of the two governments was to present Colombia to acknowledge the conflictive reality but also to show government effort at peace-making, achievements in economic growth and improvements in security, while the NGOs stressed the negative aspects of the country, ignoring or criticizing the positive side (45).

This positive and negative introduction of the Colombian conflict, most positive since governmental introduction and most negative since NGOs vision, created multiple economic and political costs. In the economic and investment field, this dual internationalization generated uncertainties among entrepreneurs and foreign investors, who, without a clear understanding of Colombian reality, induced in many instances to avoid or postpone investment in the country. In the political field, Colombia came to be seen as a country with an everlasting internal conflict, with an indefensible humanitarian situation and widespread poverty, but also as a state incapable of providing a solution, and one of the main actors responsible for the human rights violations.

Additionally, policy-makers, the academic community and civil society in the United States and in Europe had their own confused perception of Colombia reality, which determined their recommendations and, in certain circumstances led them to apply sanctions. In general, the variety of sources from which resources were to be acquired generated confusion in the international community, since the grounds for appeal to different channels, were at times contradictory. Whereas the government's position was to link international cooperation with the argument of shared responsibility for the drug problem and then to the terrorist as a threat to Colombian social development, the position of NGOs linked cooperation to social themes (46). Bearing in mind the importance of these civil society organizations and of social themes in Europe, in multilateral organizations and even in the US, this last position had a major influence.

Undermining the role of the government overseas

Deterioration of the image of Colombia and its government was not the unique bad consequence. The parallel diplomacy between non-governmental and inter-governmental sectors in Colombia, Europe and the US, also undermined the role of the Colombian government overseas.

In the US WOLA, the Washington Office on Latin America, and the US Office on Colombia are the two platforms that support Colombian NGOs parallel diplomacy. Both focused their attention on the violation of human rights and blamed the Colombian Government as an actor responsible. For WOLA Colombia is still the country with the greatest number of human rights violations and highest number of politically motivated murders per year in the Western Hemisphere (47). For the US Office on Colombia the emphasis is on the continuing human rights crisis in Colombia, and it seeks to educate US policymakers, the media and the US public about the impact of US policy on Colombia (48). Connecting members of Colombian civil society with US policy makers, and by involving US citizens in the policy-making process, this organization not only affected US perception on Colombia's reality but also, the Colombian government's relations with Washington.

In Europe and in the multilateral the Human Rights Commission of Geneva (HRCG) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) were the two scenes where these NGOs played an important role. In the Commission of Human Rights in Geneva, NGOs argued the deterioration of human rights in Colombia (49). In the ILO, the "Comisión Colombiana de Juristas" and the "Escuela Nacional Sindical" deployed transnational networks to argue the deterioration of situation of trade unionists. The High Commissioner for Human Rights had opened a permanent office in Colombian from 1995, and from 1997 the yearly reports of this Commission stated that the situation in Colombia continued to deteriorate. Additionally, from 2003 they increased the intensity of their survey once of the situation of human rights in Colombia, and made more severe the tone of their declarations (50). From 1987, yearly, the Colombian government was called on by the ILO to answer for the recurrent violation of Colombian workers' fundamental rights, and from 1998 "por no observar las recomendaciones del comité de libertad sindical y de la comisión de expertos en aplicación de normas frente a la adecuación de la legislación interna a los compromisos adquiridos con la ratificación de convenios, en especial el 87 y 98, sobre derechos de asociación y negociación colectiva" (51). In sum, Colombian NGOs work with both organizations, confused European and multilateral perception on Colombia, on its government and on Colombian foreign policy.

In general, although, Colombian governments did not plenty fulfilled stability, security, democracy and human rights, "peace organizations have often demonstrated ambivalence towards formal politics, including a distant relationship from political parties, and a critical and confrontational stance with regard to state institutions, inherited from the social struggles of the previous decades" (52). In fact, many NGOs found their space, arguments and financial support from abroad rejecting the traditional practices of the political system and showing necessity of emerging new national actors with international impact.

Affecting the Colombian international cooperation management and its decision-making foreign process

Confusion and space that Colombian and international NGOs achieved abroad and, particularly in Europe, also allowed them to introduce themselves, with recognized rights, into the decision-making process and into the agenda of cooperation established at the European "mesa de donantes".

In practice, this introduction was good since strategy of international cooperation become building between donors and local civil society. However, that introduction affected the international cooperation management of the Colombian government in two ways. First, it ceased to be directed exclusively by the government and came to be shared by organized civil society. As a result, the development of international cooperation policy emerged with two formal actors, two different formal visions and management routes (53). Second, all of those non-governmental and inter-governmental sectors in US and European highlighted the big gap between some maximalist requests dealing with the comprehensive conceptualization of peace ranged over many topics and the reduced capacity of the Colombian state in meeting them. Colombia being a country in conflict, victims were supported in their right to make themselves heard both within the country and abroad.

Regarding the first consequence, whereas the government sought dialogue at a national government level, the NGOs had direct dialogues with their international counterparts, which in many cases was more effective. The revolution in the field of this new activism has meant the end of the nation-state monopoly of its international affairs and made the "Global Civil Society" a reality (54). This added further complexity to the international relations of the country.

NGO activity at "las mesas de donantes" was an example of this. NGOs managed to move from a mere right to participation and discussion to a right of participation in decisions affecting the formulation, execution and evaluation of European cooperation policy. While in "la mesa de Madrid" in 2000 the NGOs only had participation, in "la mesa de Londres" in 2003 they intervened more directly, and in "la mesa de Cartagena" in 2005 they virtually shared responsibility with government for the new declaration of the "mesa de donantes". In London, they organized a group of 32 Colombian organizations, "la Alianza", supported by European NGOs and with the recognition of the British Foreign and Commonwell Office, and managed formalize a parallel meeting a day before the intergovernmental event. At the end, some paragraphs of the Official Declaration concerned the position of such organizations (55). In Cartagena, they together with the group of 24 (G-24) managed to consolidate a formal tripartite dialogue between the Government, the International Community and the Civil Society, and to formalize their status as actors in the discussions with the Colombian government. "La Alianza" came to be a new policy maker in the international cooperation affairs.

Regarding the second consequence, US, European and multilateral social visions in Colombia increased civil expectations and made perceptions of the Colombian state weaker than before. Within Colombia and abroad discussion began about the Colombia state: a collapsed state, a failed state, a shadow state or a weak state (56). The Journal Foreign Policy in its number May-June 2006, published for a second time the "failed states list" in which Colombia took the 27th place among 148 states analyzed. The government lost legitimacy in the eyes of a growing number of foreign readers (57).

Management of international cooperation was disorganized and full of attacks, counter-attacks and improvisation. It confused Colombia's image abroad, and deteriorated external governmental legitimacy. That situation was made more problematic by the weakness of the Colombian Foreign Ministry. In sum, it can be said that the parallel diplomacy between non-governmental and inter-governmental sectors in Colombia, Europe and the US, created, over the studied period, a panorama of relationships more political and economical than altruist. After the end of the peace process, most NGOs needed to strengthen their instruments of influence and used the diplomatic field in order to make a genuine impact among the international actors involved in the peace dynamics in Colombia.

CONCLUSIONS

The internationalization of the Colombian conflict and the execution of Plan Colombia changed the parameters and the conduct of Colombia's foreign relations. As was exposed in the previous three chapters, Plan Colombia intensified presidential diplomacy, increased the fragmentation of Colombian foreign policy-making and weakened the Foreign Minister and the Foreign Ministry. It made relations with the United States more complex, and placed more difficulties in the way of, and to some extend, weakened relations with the European Union and most of its members. Finally, as was shown in the third section, the Plan also stimulated the participation of non-government actors, principally the human rights NGO's, both nationally and internationally.

Despite some negative effects, Plan Colombia was a rational strategy which, undoubtedly, had as one of its main goals the strengthening of military aid and its military resources. Although for President Pastrana this Plan was subordinated to his peace policy, for Uribe it was to be the means to recover the national territory, weaken insurgent groups and achieve a monopoly of military force. The continuity of Plan Colombia during the two administrations shows that Uribe's policy was in important respects the continuation of that of Pastrana. To be more precise, it should be sufficient to notice that many of Pastrana's military team survived into Uribe's administration and that a good part of Uribe's civilian team had also served under Pastrana. Examples are Juan Manuel Santos, Marta Lucía Ramírez, Fernando Araujo, Mauricio González, Fabio Valencia Cosio, Luis Guillermo Giraldo, Alfonso López Caballero and Guillermo Fernández de Soto.

Plan Colombia achieved rapprochement with the US and a very substantial increasing US assistance, which the Colombian government undoubtedly needed. That this has to be recognized, but at the same time to achieve this end with the maximum of efficacy and the minimum of friction, Colombia should have paid attention to restructuring the management of the country's foreign relations, that is, more efficient Ministry, more coordination between ministries and less presidential action. The country needs a strategic plan that has a better chance of not alienating the Europe. This means, reorganizing the Foreign Ministry and giving more priority to Europe; more, not less, expenditure on foreign relations, not closing embassies for reasons of economy; more capacity to anticipate European reactions, again, more professionalism in foreign relations, better service to Embassies, more professional Ambassadors and more professional press agencies, and an urgent strategy for opinion forming. NGOs exist, and have to be taken into consideration and this implies a proper strategy. The government needs to be more aware of the difference between what goes down well in Colombia and what goes down well abroad. It means coordinating Colombia's relations with Europe and with Latin America, as Colombia also has neglected the good management of relations with neighbors, whose are also interlocutors with the European Union

Certainly, Plan Colombia gained the country essential U.S. support, and has had a high degree of success in the field of security. But its implementation, also reveled great weaknesses in the country's management of its foreign relations. In general, that weakness has been revealed as the internal security situation has improved and it surely must now be addressed.

Figure 1

COMMENTARIES

1. "La política exterior ha cambiado en sus conceptos: primero, porque incluye una multiplicidad de temas antes no considerados; segundo, porque implica diversidad de instrumentos y no solo los políticos-diplomáticos tradicionales; tercero, porque requiere de una aproximación interméstica a la realidad, que no olvide los condicionamientos y oportunidades externas, pero que tampoco haga caso omiso de las condiciones de factibilidad y las presiones de la política interna. Tal dinámica lleva a disminuir en algún grado las fronteras entre la política exterior, las políticas comparadas y la política internacional propiamente dicha". CARDONA Diego and ARDILA Martha, "Colombia y su mundo externo: dinámicas y tendencias", in ARDILA Martha and others, Colombia y su política exterior en el siglo XXI, Bogotá, Fescol, 2005, p.xvi.

2. Formally, the director of Colombian foreign policy is the President and the Foreign Ministry is the executor. The Foreign Ministry does the day-to-day work in multilateral and bilateral relations.

3. "La Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional es la entidad creada por el Gobierno Nacional con el fin de canalizar los recursos nacionales e internacionales para ejecutar todos los programas sociales que dependen de la Presidencia de la República y que atienden a poblaciones vulnerables afectadas por la pobreza, el narcotráfico y la violencia. De esta manera, se integran la Red de Solidaridad Social (RSS) y la Agencia Colombiana de Cooperación Internacional (ACCI)", in web page of

http://www.acci.gov.co/contenido/contenido.aspx?catID=3&conID=544&pagID=820, viewed on 27 October 2007.

4. "The reason is as follows: since small states are more preoccupied with survival than are the great powers, the international system will be the most relevant level of analysis for explaining their foreign-policy choices. Because weak states are typically faced with external threats to national survival, foreign policy will reflect an attentiveness to the constrains of the international environment and foreign-policy goals will be less constrained by the domestic political process. By contrast, domestic politics will necessarily play a greater role in an explanation of great power foreign policy. Generally speaking, great powers are faced with a lower level of external threat in comparison to small states and thus have more options for action. This increased range of choice will tend to make foreign policy formation more susceptible to domestic political influence. Consequently, unit level variables cannot be ignored when explaining great power foreign policy", FENDIUS Elman Miriam, "The Foreign Policies of Small States: Challenging Neorealism in its Own Backyard, in British Journal of Political Science,Vol. 25, No. 2. April 1999, p. 175.

5. GARCIA Andelfo, "Plan Colombia y ayuda estadounidense", in RESTREPO Luís and others, El Plan Colombia y la internacionalización del conflicto, Bogotá, IEPRI-Edt. Planeta,2001,p. 194.

6. The U.S. support to Colombia was arranged at mids 2000. It had important military support in equipment and training.

7. A "Plan Marshall" for Colombia was proposed during Pastrana's electoral campaign and presented to the Clinton government on 3 August 1998.

8. "En 1998 prácticamente ningún candidato se apartaba de buscar una negociación con la guerrilla, cuando cuatro años atrás casi nadie se planteaba esa posibilidad", PASTRANA Andrés, La palabra bajo fuego, Bogota, Planeta, 2005. p. 149.

9. One of the main worries for that time was the increase of guerrillas attacks. It was clear that Colombian Armed Forces needed to be strengthened in terms of profesionalization, intelligence and technology. In fact "entre 1994 y 1998, el Ejército se había consolidado, como un actor más de la violencia al perder parcialmente su rol protagónico como encargado del monopolio del uso de la fuerza". Andrés DÁVILA and others, "El Ejército Colombiano durante el período Samper: Paradojas de un proceso tendencialmente crítico", en Revista Colombia Internacional, número 49/50, in page web of http://www.lablaa.org/blaavirtual/revistas/colinter/davila.htm, viewed on 8 March 2008.

10. "Los problemas de fondo estaban ahí: la pobreza, el conflicto armado, la debilidad de las relaciones internacionales y el narcotráfico. Todo ello conformaba el núcleo de nuestras dificultades.", PASTRANA Andrés and GÓMEZ Camilo, La palabra bajo fuego, Bogota, Planeta, 1995, p. 41.

11. PASTRANA Andrés and GÓMEZ Camilo, La Palabra bajo Fuego, Bogotá, Planeta, 2005, pp. 48-51.

12. Andelfo GARCÍA, "Plan Colombia y ayuda estadounidense", in RESTREPO Luís and others, El Plan Colombia y la internacionalización del conflicto, Bogotá, IEPRI-Edt. Planeta, 2002,p. 200.

13. Although the U.S. had begun to consider how to revise its Colombia policy should Serpa be elected, they naturally preferred Pastrana, who represented a complete break with the Samper administration.

14. PASTRANA Andrés and GÓMEZ Camilo, La palabra bajo el fuego, Bogota, Planeta, 2005, p. 118.

15. It is important to consider that originally in terms of security "el Plan Colombia solo consistió en el apoyo y mantenimiento con dinero de EU a una brigada antinarcóticos del ejercito en entrenamiento armamento y recursos para movilización. Esa brigada fue compuesta de tres batallones, 30 helicópteros pesados y 30 medianos. La policía recibe financiación en su programa anti narcoticos que incluye el mantenimiento y operación de helicópteros y el de aviones de fumigación. El impacto en el resto del ejercito, que son mas o menos treinta brigadas, o sea cien o mas batallones es limitada o nula", Online Interview with Rafael Pardo, member of Pastrana's team in 1998, 26 March 2007.

16. "Si bien es cierto que el Ministerio de Defensa de Colombia mantuvo un bajo perfil en el proceso de formulación del Plan Colombia, su participación no fue menos efectiva al quedar incorporada la aparte substancial de la estrategia antidrogas promovida por las Fuerzas Militares, que implicaba un cambio importante al colocar un nuevo hincapié en su propia participación en la lucha antinarcóticos", PASTRANA Andrés and GÓMEZ Camilo, La palabra bajo el fuego, Bogota, Planeta, 2005, pp. 203-204.

17. "En la última década, las relaciones de Estados Unidos con Colombia, habían sido lideradas por el Departamento de Estado, seguido por el de Justicia, la DEA, el CSN y la Oficina de Política Nacional de Control del Narcotráfico (ONDCP). Un menor protagonismo había tenido otros Departamentos como los de Defensa, Comercio y Tesoro. Sin embargo, esta situación tuvo algunos cambios, especialmente (...) por un mayor protagonismo del zar Antidrogas, quien ha asumido crecientemente un papel más político y hasta diplomático".A. GARCIA, "Plan Colombia y ayuda estadounidense", in RESTREPO Luís and others, El Plan Colombia y la internacionalización del conflicto, p. 220.

18. "Creado por la Ley 487 del 24 de diciembre de 1998 y reorganizado por el Decreto 1813 del 18 de septiembre de 2000 y por el Decreto 1003 del 29 de mayo de 2001, como principal instrumento de financiación de programas y proyectos estructurados para la obtención de la Paz". in web page of Acción Social, http://www.accionsocial.gov.co/contenido/contenido.aspx?catID=3&conID=544&pagID=825, viewed on 27 October 2007.

19. "Creada porel Gobierno Nacional con el fin de canalizar los recursos nacionales e internacionales para ejecutar todos los programas sociales que dependen de la Presidencia y que atienden a poblaciones vulnerables afectadas por la pobreza, el narcotráfico y la violencia". in web page of Acción Social, http://www.accionsocial.gov.co/contenido/contenido.aspx?catID=3&conID=544&pagID=825, viewed on 27 October 2007.

20. Personal interview with Bruce Bagley, Quito, 30 October 2007.

21. Personal interview with Bruce Bagley, Quito, 30 October 2007.

22. MITCHELL Christopher, "¿Una espiral descendente? Sobre cómo se elabora la política de los Estados Unidos hacia Colombia", in RESTREPO Luís, Estados Unidos Potencia y prepotencia, Bogotá, TM Editores, 1998, p. 4.

23. Presidency of Colombian Republic, "Bush brinda total respaldo a Colombia", November 2004, in web page of http://noticias.presidencia.gov.co/prensa_new/sne/2004/noviembre/22/06222004.htm, viewed on 27 October 2007.

24. REYNOLDS Paul, "Las batallas de poder en Washington", in BBC Mundo, Wednesday 17 November 2004, in web page of http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/spanish/international/newsid_4017000/4017965.stm, viewed on 27 October 2007.

25. Telephonic interview with Michael Shifter, Vice President-Policy Inter-American Dialogue, 2 November 2007.

26. RICE Condoleezza, "Aunque el plan Colombia termine, el compromiso de Colombia con EU sigue", Monday 23 September 2006, Colombian Presidency, in web page of http://www.presidencia.gov.co/sne/2005/abril/27/14272005.htm, viewed on 27 October 2007.

27. MITCHELL Christopher, "¿Una espiral descendente? Sobre cómo se elabora la política de los Estados Unidos hacia Colombia, in RESTREPO Luís, Estados Unidos potencia y prepotencia, Bogotá, 1998,p. 27.

28. "La DEA y Colombia se unen contra el tráfico de drogas", in Voanews, Wednesday 5 November 2003, in web page of http://www.voanews.com/spanish/archive/2003-11/a-2003-11-05-12-1.cfm, viewed on 28 October 2007.

29. The White House, "The National Security Strategy, September 2002", in web page of http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/nss/2002/nss4.html, viewed on 28 October 2007.

30. Personal interview with Bruce Bagley, Quito, 30 October 2007.

31. LIZARZABURU Javier, "EE.UU. reducirá ayuda a Colombia", in BBC Mundo, Thursday 10 August 2006, in web page of http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/spanish/latin_america/newsid_4778000/4778865.stm, viewed on 28 October 2007.

32. The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), a component of the Executive Office of the President, was established by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. See web page of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), in web page of http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/about/index.html, viewed on 28 October 2007.

33. Colombian Presidency, "Congreso y Gobierno de EU definen éxito del Plan Colombia", 11 May 2005, in web page of http://noticias.presidencia.gov.co/prensa_new/sne/2005/mayo/11/19112005.htm, viewed on 28 October 2007.

34. HERSMAN Rebecca, Friends and Foes: How Congreso and the Presidente really make Foreign Policy, Washington, The Brooking Institutions, 2000.

35. European Parliament Resolution on Plan Colombia and the support to peace process in Colombia, Paul-Emile Dupret, European Parliament resolution on Plan Colombia and support for the peace process in Colombia, 1 February 2001.

36. European Commission, "Albania - EU-Albania relations", in web page of http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/albania/eu_albania_relations_en.htm, viewed on 8 Mars 2008

37. European Commission, "Relaciones con terceros países", in web page of http://europa.eu/scadplus/leg/es/s05050.htm, viewed on 8 Mars 2008.

38. European Commisión, "The EU's relations with Colombia", in web page of http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/colombia/intro/index.htm#4, viewed on 8 Mars 2008.

39. Social Action, "2007 Cooperation map's statistics", in page web of http://www.accionsocial.gov.co/acci/web_acci/nuevomapa/bienvenida.html, viewed on 3 November 2007.

40. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, "Decreto Numero 19 de 1992, Decreto Numero1295 de 2000, Decreto Numero 2105 de 2001", Bogotá.

41. PACHON Rocío, "la gestión y la negociación de Colombia ante la UE frente a un caso de estudio como es el Sistema Generalizado de Preferencias / SGP Régimen droga y SGP Plus", Working Paper, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, No. 15, 2006.

42. "Durante el primer semestre de 2003, la Comisión Europea analizó la nueva cláusula de graduación puesta al SGP-droga y por razones de competitividad, empezó a preparar su informe para que Colombia perdiera las preferencias arancelarias concedidas al sector cinco de su producción hacia Europa -flores, frutas y hortalizas-". See PACHON Rocío, "La gestión y la negociación de Colombia ante la UE frente a un caso de estudio como es el Sistema Generalizado de Preferencias / SGP Régimen droga y SGP Plus", Working Paper, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, No. 15, 2006.

43. Virginia M. Bouvier, "Civil Society under Siege in Colombia", Special Report 114, 2003.

44. Those NGOs voices and activities also created internal confusion, affected the governmental legitimacy and the civil-militar cooperation, and created many unfinished projects.

45. Several explanations can contribute to understand that the NGOs' behavior, and among these, one is their interest in obtaining resources, and that these resources depended greatly on the degree of sensitiveness aroused in donors. Video projections, photographic exhibitions, and other more activities in which the effects of the Colombian conflict were shown, can be party understood as fund-raising.

46. Many scholars consider Uribe's arguments to the EU a mistake. It was clear that many in the EU considered the military option to counter terrorism was not the way.

47. WOLA, "Colombian programme", in web page of http://www.wola.org/?&option=com_content&task=blogsection&id=6&Itemid=&topic=Colombi, viewed on 8 March 2008.

48. US Office on Colombia, "About Colombia", in web page of http://www.usofficeoncolombia.com/Mission%20and%20Strategic%20Vision/, viewed on 8 March 2008.

49. This Commission was created in 1946 in the UN. It can take individual demands and to study a country situation if it was demanded either by particulars or non governmental organizations.

50. It resulted of the Colombian President speech where it said that "las ONG estaban divididas en tres categorías básicas: (1) las ONG teóricos, que él dice respetar pero con los que en gran parte no

concuerda; (2) 'organizaciones serias de derechos humanos', con las que el está dispuesto a dialogar; y (3) 'organizaciones politiqueras que están

al servicio del terrorismo y que esconden sus ideas políticas detrás del discurso de los derechos humanos'. Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano 2003, Boletín Incidencia y Compromiso "Se deterioran las relaciones entre el Presidente Uribe y las ONG colombianas", in web page of http://indh.pnud.org.co/articuloImprimir.plx?id=159&t=informePrensa, viewed on 8 November 2007. See also "Declaración conjunta de organizaciones no gubernamentales y sectores sociales colombianos con motivo del 54º período de sesiones de la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de Naciones Unidas (16 de marzo a 24 de abril de 1998)"in web page of http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/colombia/doc/conjun.html, viewed on 28 October 2007.

51. RIOS Noe Navarro, "OIT nombra observador especial en materia de libertad sindical y seguridad de los sindicalistas colombianos", Escuela Nacional Sindical, Bogotá, 2000, in web page of http://www.oit.org.pe/sindi/general/documentos/inforoit.html, viewed on 28 October 2007.

52. FERNÁNDEZ Carlos and others, "Peace mobilization in Colombia 1978-2002", Conciliation Resources, 2004, in web page of http://www.c-r.org/our-work/accord/colombia/peace-mobilization.php, viewed on 11 September 2008.

53. Ibid. "It is important not to forget that there are tensions and differences amongst NGOs perspectives, not only because of different concepts of peace (peace as the military defeat of the enemy, peace as demobilization, peace implying greater democracy, and peace as social justice), but also because some topics generate serious debate and controversy: the legitimacy of the armed struggle, the parameters of negotiations, and the issue of security".

54. IGNATIEFF Michael, Los derechos humanos como política e idolatría, España, Paidos, 2003, p. 35.

55. "Otros dos párrafos se refirieron al tema de la cooperación y catorce más a las distintas acciones que tenía que tomar el gobierno colombiano, entre ellas una lista de condiciones referentes a derechos humanos, paramilitarismo y al cumplimiento de las recomendaciones de la oficina del Alto Comisionado". Personal Interview with Antonio Madariaga, Director of Viva la Ciudadanía, Bogotá, 23 October 2007.

56. PIZARRO Eduardo and BEJARANO Ana, "Beyond Armed Actors: A Look at Civil Society",Harvard University's Magazine, Spring 2003, in web page of http://www.drclas.harvard.edu/revista/articles/view_spanish/235, viewed on 8 Mars 2008.

57. PIZARRO Eduardo and BEJARANO Ana, "Beyond Armed Actors: A Look at Civil Society".

REFERENCES

1. "Declaración conjunta de organizaciones no gubernamentales y sectores sociales colombianos con motivo del 54º período de sesiones de la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de Naciones Unidas (16 de marzo a 24 de abril de 1998)"in web page http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/colombia/doc/conjun.html, viewed on 3 October 2007. [ Links ]

2. Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional, "Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional" in web page of http://www.acci.gov.co/contenido/contenido.aspx?catID=3& conID=544& pagID=82, viewed on 2 October 2007. [ Links ]

3. Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional, "Fondo de Inversión Para la Paz" in web page of http://www.accionsocial.gov.co/contenido/contenido.aspx?catID=3& conID=544&pagID=825, viewed on 2 October 2007. [ Links ]

4. Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional, "2007 Cooperation map's statistics", in page web of http://www.accionsocial.gov.co/acci/web_acci/nuevomapa/bienvenida.html, viewed on 3 November 2007. [ Links ]

5. Contraloría General de la Republica e Colombia, "Plan Colombia: tercer informe de evaluación", Bogota, Julio de 2002. [ Links ]

6. Contraloría General de la Republica de Colombia, "Plan Colombia, primer informe de evaluación", 30 Agosto 2001. [ Links ]

7. European Commission, "Albania - EU-Albania relations", in web page of http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/albania/eu_albania_relations_en.htm, viewed on 8 March 2008. [ Links ]

8. European Commission, "Relaciones con terceros países", in web page of http://europa.eu/scadplus/leg/es/s05050.htm, viewed on 8 March 2008. [ Links ]

9. European Commission, "The EU's relations with Colombia", in web page of http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/colombia/intro/index.htm#4, viewed on 8 March 2008. [ Links ]

10. European Parliament, "Resolution on Plan Colombia and the support to peace process in Colombia", European Parliament resolution on Plan Colombia and support for the peace process in Colombia, 1 February 2001. [ Links ]

11. Pastoral Social - Cáritas Panamá, "Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano 2003 se deterioran las relaciones entre el Presidente Uribe y las ONG colombianas", in web page of http://indh.pnud.org.co/articuloImprimir.plx?id=159& t=informePrensa, viewed on 8 November 2007. [ Links ]

12. The White House, "Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP)" in web page of http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/about/index.html, viewed on 2 October 2007. [ Links ]

13. The White House, "The National Security Strategy, September 2002", in web page of http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/nss/2002/nss4.html, viewed on 2 October 2007. [ Links ]

14. US Office on Colombia, "About Colombia", in web page of http://www.usofficeoncolombia.com/Mission%20and%20Strategic%20Vision/, viewed on 8 Mars 2008. [ Links ]

15. WOLA, "Colombian programme", in web page of http://www.wola.org/?& option=com_content& task=blogsection& id=6& Itemid=& topic=Colombia, viewed on 8 Mars 2008. [ Links ]

16. AYOOB Mohamed, "Security in the third world: the worm about to turn?, in International Affairs, Vol. 60, No. 1, Winter, 1983-1984. [ Links ]

17. AYOOB Mohamed, "The third world in the system of states: Acute schizopherenia or growing pains?, in International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 1, Mars, 1998. [ Links ]

18. BUENO DE MESQUITA Bruce and Other, War and Reason: Domestic and international imperatives, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1992. [ Links ]

19. CARAJAL Leonardo and other, "La política exterior de la administración Uribe (2002-2004), Alineación y Securitización", Bogotá, 2005. [ Links ]

20. CARDONA Diego and ARDILA Martha, "Colombia y su mundo externo: dinámicas y tendencias", in ARDILA Martha and others, Colombia y su política exterior en el siglo XXI, Bogotá, Fescol, 2005. [ Links ]

21. CARVAJAL Leonardo, "Tres años del gobierno Uribe (2002-2005): Un análisis con base en conceptos dicotómicos de política exterior", in OASIS, N.11, Bogotá, Universidad Externado, 2006. [ Links ]

22. CEPEDA Fernando and others, "El Plan Colombia", September 2000, in web page of http://www.idl.org.pe/idlrev/revistas/131/pag67.htm, viewed on 25 march 2007. [ Links ]

23. CEPEDA Fernando, "Avaro Uribe:Dissident", Inter American Dialogue, Working Paper, August 2003. [ Links ]

24. CLAPHAM Christopher (ed.), Foreign Policy Making in Developing States, Saxon House,1977 [ Links ]

25. DÁVILA Andrés and others, "El Ejército Colombiano durante el período Samper: Paradojas de un proceso tendencialmente crítico", en Revista Colombia Internacional, número 49/50, in page web of http://www.lablaa.org/blaavirtual/revistas/colinter/davila.htm, viewed on 8 March 2008. [ Links ]

26. FENDIUS Elman Miriam, "The Foreign Policies of Small States: Challenging Neorealism in its Own Backyard, in British Journal of Political Science,Vol. 25, No. 2. April, 1999. [ Links ]

27. GARCIA Andelfo, "Plan Colombia y ayuda estadounidense", in RESTREPO Luis and others, El Plan Colombia y la internacionalización del conflicto, Bogotá, IEPRI-Edt. Planeta, 2001. [ Links ]

28. HARDEN Sheila, Small is dangerous: Micro-States in a Macro World, London, Cambridge University Press, 1985 [ Links ]

29. HERSMAN Rebecca, Friends and Foes: How Congreso and the Presidente really make Foreign Policy, Washington, The Brooking Institutions, 2000. [ Links ]

30. HILL Christopher, The Changing Politics of Foreign Policy, London, Palgrave Macmillan 2003, p. 35. [ Links ]

31. HOLBRAAD Carsten, Middle Powers in International politics, London, St. Martin's Press, 1984. [ Links ]

32. IGNATIEFF Michael, Los derechos humanos como política e idolatría, España, Paidos, 2003. [ Links ]

33. KEOHANE Robert and Nye JOSEPH, "Complex interdependence and the role of force", in R. Art and R. Jervis (comp.), International Politics: Enduring Concepts and Contemporany Issues, New York, Longman. [ Links ]

34. KISSINGER Henry, Does the Americas need a Foreign Policy? Toward Diplomacy for the 21st Century, New York, 2000. [ Links ]

35. LEAL Francisco, "Crisis de la Region Andina: Fragilidad democratica, Inestabilidad social y Plan Colombia", in K. Bodemer, (ed), El Nuevo Escenario de (In)seguridad en America Latina, amenazas para la democracia?, Santiago, 2003. [ Links ]

36. MASSON Ana, "Colombia's Democratic security agenda: public order in the security tripod", Oslo, Security Dialogue, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2003. [ Links ]

37. MITCHELL Christopher, "¿Una espiral descendente? Sobre cómo se elabora la política de los Estados Unidos hacia Colombia", in RESTREPO Luis, Estados Unidos Potencia y prepotencia, Bogotá, TM Editores, 1998. [ Links ]

38. PACHÓN Rocío, "la gestión y la negociación de Colombia ante la UE frente a un caso de estudio como es el Sistema Generalizado de Preferencias / SGP Régimen droga y SGP Plus", Working Paper, No. 15, Bogotá, 2006. [ Links ]

39. PASTRANA Andrés, La palabra bajo fuego, Bogota, Planeta, 2005. [ Links ]

40. PIZARRO Eduardo and BEJARANO Ana, "Beyond Armed Actors: A Look at Civil Society",Harvard University's Magazine, Spring 2003, in web page of http://www.drclas.harvard.edu/revista/articles/view_spanish/235, viewed on 8 Mars 2008. [ Links ]

41. RAMIRÉZ Socorro, El Plan Colombia y la internacionalización del conflicto, Bogota, 2001. [ Links ]

42. ROJAS Diana, "La política internacional del Gobierno de Pastrana en tres actos", in Análisis Político, No. 46, Bogota, IEPRI, 2005. [ Links ]

43. ROJAS Diana, "La política internacional del Gobierno de Pastrana en tres actos", in Análisis Político, No. 46, Bogota, IEPRI, 2005. [ Links ]

44. ROJAS Diana, A. León, and A. García, El Plan Colombia y la paz: la internacionalización del conflicto, Bogota, IEPRI, 2001. [ Links ]

45. SINGER J. D., "The level of analysis problem in International Relations, in World Politics, No. 14, 1961. [ Links ]

46. WALTZ Kenneth, The State and War: A theoretical analisis, New Cork, Columbia University Press, 1959. [ Links ]

47. "La DEA y Colombia se unen contra el tráfico de drogas", in Voanews, Wednesday 5 November 2003, in web page of http://www.voanews.com/spanish/archive/2003-11/a-2003-11-05-12-1.cfm, viewed on 28 October 2007. [ Links ]

48. LIZARZABURU Javier, "EE.UU. reducirá ayuda a Colombia", in BBC Mundo, Thursday 10 August 2006, in web page of http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/spanish/latin_america/newsid_4778000/4778865.stm, viewed on 28 October 2007. [ Links ]