INTRODUCTION: POLITICAL POLARIZATION IN THE DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM

The political forces of the so-called international far-right-wing populism use a simple and polarized discursive strategy (Fernández-Villanueva & Bayarri, 2021). Actors and social forces are divided into good and bad, exaggerating the importance of the opposites and denying any semantic space between the polarized categories. As Burdett (2003) argues, the construction of antagonists based on videos, texts, and images was also characteristic of the period of twentieth-century fascism. Exaggeration and simplification are not seen as inadequate or disturbing strategies of political discourse but are normalized and extended (Gallardo, 2018; Bizberge & Segura, 2020). This discursive polarization has clearly emerged in recent far-right communication (Bakir & McStay, 2018; Ardèvol-Abreu, 2022; Canavilhas et al., 2019; Canavilhas & Colussi, 2022).1

In recent electoral campaigns, especially since the Trump era, political communication has found in the digital sphere a strong ally for the rapid and effective dissemination of messages (Gomes-Franco & Colussi, 2016; Dader, 2020). Moreover, social networks have become a propitious scenario for the creation of symbolic realities entrenched in the subjective tendency of post-truth and the viralisation of contents disseminated without prior contrast (Arias-Maldonado, 2016; Berrocal Gonzalo, 2017; Bayarri, 2022).

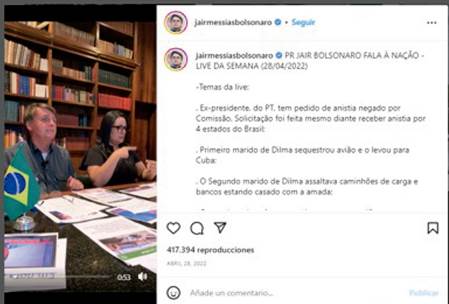

This study is based on monitoring the online communication strategies of Jair Bolsonaro, who was in charge of the Brazilian government until the end of 2022. One of his main political communication actions consisted of transmitting a weekly Live broadcast from his Instagram profile (@jairmessiasbolsonaro). The former president employed a self-legitimized scenario to consolidate himself as the sole representative of the federal government’s communication and the bearer of truth over the media and other political forces.

In this sense, political content published on social networks is characterized by speed and excess (Zafra, 2017). Both the images and videos disseminated promote a rapid expansion of political content, whether informative or of an opinion nature, while, at the same time, slowing down the in-depth reproduction of reasoned argumentation (Campos, 2020). These characteristics reinforce the role of political and social polarization in this format, where the audience tends to pay more attention to the aesthetic, communicative, and compositional elements of the environment. This is what Freidin et al. (2022) call a form of “affective polarization.” This affective polarization has increased in asymmetrical terms in recent years, impacting most strongly on far-right supporters. Thus, social networks are transformed into a vehicle that facilitates the processes of political radicalisation, not only on the far-right but mainly affecting the latter (Fuks & Marques, 2022; Jiménez & Sánchez-Mora, 2021).

This direct and disintermediated communication was also used by Jair Bolsonaro during the 2022 election campaign as part of his strategy to win re-election (Gomes-Franco et al., 2022). Eventually, the Workers’ Party (PT, for its acronym in Portuguese) candidate, Lula da Silva, won in a close contest with Bolsonaro, receiving 50.9% of the votes (Galarraga, 2022).

Lula assumed the driving seat in a divided and highly polarized country in which violence took center stage in the attacks that occurred a few days after the current president’s inauguration:

For about four hours, thousands of far-right supporters of former president Jair Bolsonaro assaulted Brazil’s three powers of the state—the Congress, the Supreme Court, and the presidential palace—calling for a military coup and demanding the destitution of the current president Lula (Polglase et al., 2023).

Political adversaries are transformed into enemies and can therefore be attacked (Hodson et al., 2014; Zlobina & Andujar, 2021). In this line, both “digital populism” (Cesarino, 2020) and “pop far-right” (Goldstein, 2019) have become highly relevant objects of study in the field of political communication.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Subjectivity and Symbolism: The Construction of the “Bolsonarist Folk”

In the last decade, studies on personalism, supremacy, populism, and their relations to the far-right phenomenon in Latin America have deepened. These studies have focused on problematising the concept of populism, aiming to understand its regional particularities in their specific historical, social, and political contexts (Gidron & Hall, 2017; Mansbridge & Macedo, 2019). Studies on personalism and supremacism have sought to understand the weaknesses of public institutions and presidentialist constitutionalism in the emergence of different forms of authoritarianism in Latin America (Hawkins, 2010; Horowitz, 1999; Landau, 2020). According to Moffitt (2016), populism is a political style, the essence of which lies primarily in the mediated performances of leaders rather than in the content or ideology of the political system.

For some academics (e.g., Laclau & Mouffe, 2004; Mouffe, 2005), moments of high dramatization and personalistic exaltation, such as the period before elections, would be cataloged as populist moments. In this exceptional time, political identification occurs in two ways: the leader embodies values and ideas among society, while sympathisers embody the leader (Weber, 1992; Da Matta, 1983). In this period, ideas and proposals are ordered through elements that facilitate an understanding, elements society identifies with, and that mobilize emotionally towards a new stage, channelled through these political hero-leaders (Errejón & Mouffe, 2015; Christofoletti, 2022).

Drawing on Ernesto Laclau’s conception of populism (2005), three foundational strategies organize the identity of the Bolsonarist phenomenon: chain of equivalence, empty signifier, and antagonistic frontier. Bolsonarism arranges its political module of collective mobilization via these three Laclauian notions. We use these concepts as analytical categories to study some of the main symbolic constructions of Bolsonaro’s Live broadcasts.

The first one, a “chain of equivalence,” allows for chaining multitudes of demands from different social forces and factions to be channelled to create inertia against the status quo. Every social force—point of the chain—has its own distinct position, position-taking, and relation to existing hegemony.

Laclau is explicit here; for him, “equivalent” does not equate to “being identical.” They are not exploited or alienated in the same way. Each point of the chain remains singular, yet they collectively operate in unison (Soares et al., 2018). Here, the symbol becomes the key unifying and mobilizing emblem that aggregates and concretises sectional particularism into a mass demand (Mendonça & Caetano, 2021).

An empirical example is the political crisis in Brazil that started in 2013. Chronologically, the key public events that shaped this shift were economic demonstrations in June 2013, protests during the 2014 World Cup, public demonstrations demanding the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2015, and military intervention in Rio de Janeiro in 2018. What began in 2013 as a pluralist expression of disaffection by various sectors acquired a distorted form until the discontent of the conservative sectors was gradually channelled into the Bolsonarist project. Through symbols, Bolsonarism acquired the character of a political phenomenon, capable of channelling and representing the country’s conservative demands. All these demands were organized in chains of equivalence, which gained meaning and order by using symbols that acted as “empty signifiers” (Bayarri, 2022).

The second concept, linked to the first, is “empty signifier,” which allows for conjoining disparate social energies and demands via creating a link between equivalence and representation apropos the one unique empty signifier (the leader, the slogan, imagery, or symbolism). At this historical moment that we can call a “Window of Opportunity” (readapting Gramsci’s concept of the crisis of hegemony (Gramsci, 1971; Gramsci, 1978)), Bolsonarism began to signify such chains of equivalence through various symbolic strategies and symbolism (Umpierrez de Reguero et al., 2022).

Symbolism is the vehicle and the strategy of organizing the new (Pérez-Curiel & Limón-Naharro, 2019). In this sense, we see the crisis of subjectivity in our world as the crisis of renaming the already named against the inertia of the historical count.

The third concept, “antagonistic frontier,” allows inverting existing hierarchies via restructuring the binary in favour of “good citizens” against “bandits.” In the construction of a collective subject called the “folk,” Bolsonarism, following Laclau and Mouffe (2004), attempts to redefine the frontier of political identification by strengthening the rhetoric of political polarization: we against them. The Bolsonarist folk is the mass chain of equivalence beyond a specific ideological identity. For the organization of this chain of equivalence, it is fundamental that there would be an enemy, an identified culprit, who would group all demands into a common field (Ruiz, 2021).

The telos of this strategy is “transversality,” which is the re-conceptualisation, renaming, and valorisation of certain symbolisms in service of the Bolsonarist exclusionary political project (Serrano, 2019).

Digital Populism: A President as an Influencer Figure

Brazil is a country with a growing number of social media users (Nasir et al., 2018; Da Silveira, 2017; 2019), who have become a relevant target audience for far-right actors to exploit communications technology to advance their ideology and diverse economic interests (De Gregorio & Goanta, 2022). Although the use of online platforms for the dissemination of political propaganda, collective mobilization, and discursive construction of the far-right has been widely studied in Western countries (Gheorghe, 2019; Conway et al., 2019), a gap exists in terms of how the far-right operates in the Global South, especially in Brazil.

The country presents a growing group of political influencers with a presence on various social networks, where they build audiences and sell far-right ideology through intimate and accessible relationships with the audiences of their content (Lewis, 2018). Influencers are authentic communicators on social media and can be defined as opinion leaders active on social networks (Lewis, 2018). These users have a high number of followers, are admired, followed by the public, and heard by the crowd (Romero et al., 2011). In the case of political influencers, they are often celebrities who are very effective in fusing political content with personal branding communication techniques to gain audience and followers (Casero-Ripollés, 2020; Berrocal Gonzalo, 2017; Leidig & Bayarri, 2022).

Regarding the phenomenon of “Instafame,” Marwick (2015) argues that it is a “variety of celebrity” who manages a mentality and a set of self-presentation practices endemic to social media. As for political influencers, they strategically design a profile, target followers, and reveal personal information about their habits and non-verbal forms of expression to increase attention and thus enhance their online status (Senft, 2013).

Previous studies indicate that political influencers in Brazil begin by focusing their attention on fashion and aesthetic issues and then turn toward strategic elements to establish a political brand (Da Silva & Tessarolo, 2016). Political influencers are mainly characterized by the following aspects that determine whether they enjoy celebrity traits: reach, resonance, and relevance (Time Influency.me, 2019; Arias-Maldonado, 2016). They are usually bearers of authority on social networks, as they have become opinion leaders and stand out for their testimonials and for having legitimacy to validate the content they transmit via Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube (Maly, 2020).

This figure of the political influencer is often legitimized and supported by the dynamics surrounding influencer marketing, specifically by what is known as micro-influencers. In the case of politicians, they tend to take advantage of the supporters of their parties without the need to create them from scratch (Fullana, 2022).

One of the techniques most used by Jair Bolsonaro, in which he acted as a political influencer and celebrity, was decontextualisation. The former president took advantage of different online platforms to construct new meanings through concrete objects, such as the construction of a discourse around reducing violence in Brazil after the release of licenses for the use of firearms.

In this scenario of information bubbles and disorder in which the political consolidation of far-right movements occurs, the production of truths has passed into the hands of political influencers. These truths, issued through comments and testimonies, substantiate and validate the content they transmit in a dynamic that potentiates disinformation and political polarization (Colussi, 2020; Beraba, 2022). Also, the digital spaces maintained by these influencers can constitute a new kind of third space where the emergence of political topics can have a greater impact on the political behavior of the influencers’ followers (Suuronen et al., 2022).

In this way, influencers act as gurus, self-proclaiming their authority base and rejecting the validation of their knowledge by scholarly institutions and empirical demonstration (Peres-Neto, 2022). This production of truths in social networks related to the communicative strategies of far-right parties has been referred to as “pop far-right” (Goldstein, 2019) or “digital populism” (Cesarino, 2020; Gerbaudo, 2018).

METHODOLOGY

This research is based on the analysis of ten Lives emitted by Jair Bolsonaro in February-May 2022, during the pre-electoral period of the presidential elections of October 2022 in Brazil. The audiovisual sample analyzed, reaching a total of 8 hours, 3 minutes, and 11 seconds, is available in its entirety on the former president’s Instagram profile (@jairmessiasbolsonaro), an account followed by more than 25.2 million users, which represents around 12% of Brazil’s current population.

The mentioned analytical period is considered fitting given the strategic relevance of political communication in pre-electoral periods. In this sense, the general objective of the study is to identify the main discursive elements that operate in the construction of the image of an influencer candidate based on the authority granted by the position that Bolsonaro then held as President of the Republic.

The research question that guided the analysis is set out below:

RQ: How does Bolsonaro use populist techniques to address his audiences?

The methodology used in this analysis consists of a qualitative approach based on the study of the scenarios and use of verbal and non-verbal language in these videos. The exploration of the phenomenon through qualitative techniques promotes an inductive approach to the object of study, allowing it to be characterized and understood from its own dynamics and can offer significant findings (Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

The approach to RQ has, therefore, a triangular perspective, which contemplates pragmatics, visual studies, and grounded theory:

The proposal of the pragmatic analysis of language developed by Escandell (2013) problematises the conventional meaning of words, favouring a reading of what the subject has meant to say based on what they have actually said. In this analytical system, we consider the following elements of discourse: the context, the intentionality of the speaker, and the social relationship between the speaker and their interlocutors. In this sense, pragmatics transcends the use of language, purely rooted in the grammatical elements that support it, to understand the multiple dimensions of the statement

Audiovisual language is another fundamental element in this study, approached from the methodology of visual studies (Serrano, 2008; Serrano & Zurdo, 2012; Ballesteros, 2015; García et al., 2016). This methodological approach considers the image, fixed and dynamic, to be the central component of the analytical process proposed by visual sociology. From this perspective, the imagistic object is recognised for its potential for influence, generating force fields that interact with the discourse and establish hotspots according to communicative intentionality

Finally, grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1994) supports the pillars of this methodological triangulation based on the extraction and analysis of textual data, the selection of representative quotes from the discourse analyzed, and their subsequent coding. This process of interpretative analysis systematises qualitative research and generates correlations that could be concretised in the gradual elaboration of hypotheses derived from the results obtained. Grounded theory is considered to offer relevant tools for the study of novel phenomena that lack previous categories

RESULTS: STRATEGIES OF THE INFLUENCER BOLSONARO

Homemade videos and the transmission of Lives through social networks were the contents that most mobilised voters in terms of views and interactions during Bolsonaro’s electoral campaign in 2018 (Brandão Júnior, 2022). These types of videos continued to support the actions carried out during the four years of his government and the 2022 presidential campaign.

The results point to the use of some of the typical elements of populism and unreferenced opinion, as well as attacks on the press and journalists, as the main resources employed by Bolsonaro as an influencer to obtain his political achievements. These resources are reflected not only in his speech but also in the video scenario and non-verbal communication, which combine 1) the dichotomy of good—his government and supporters—and evil, represented by the opposition and the press; 2) conservatism anchored in the values of family, fatherland, and God; 3) aggressiveness; and 4) the dissemination of fake news.

This political strategy of the influencer Bolsonaro is based on disintermediated communication (Gomes-Franco et al., 2022; Abdulmajeed & El-Ibiary, 2020) that favours disinformation and political polarization, as can be confirmed from the description and analysis of the results presented below.

Elements Regarding Populism

Bolsonarism has formed and matured hand in hand with the emergence of a set of symbolisms that aggregates fragmented and disjointed multiples into unified majorities—albeit an ephemeral unity in struggle and motion (Ortiz, 2022). Some of the main symbols that have accompanied and reinforced the movement’s narrative are the reinterpretation of the idea of “patriotism,” the redefinition of the flag, the national anthem, and the concept of “citizenship.”

In the Lives broadcasted on Thursdays at 7 pm (local time in Brasilia), Bolsonaro assumes the role of a presenter and political leader who informs his followers on social networks. The video scenarios alternate between an office with a library full of books and a supposedly improvised space with the Brazilian flag in the background, elements that, respectively, refer to knowledge and the fatherland. The clothing worn by the president in these live performances varies between a suit with a tie and casual short-sleeved shirts (see Figure 1), one of the elements that make him look like an ordinary citizen.

These videos, characterized by a homemade production using a mobile device, favour the informality of Bolsonaro’s gestures and speech. In front of the camera and in the foreground, the president looks at his Casio watch—an inexpensive, plastic watch with which he tries to identify himself as a man of the people, without showing habits of excess, as opposed to the corruption and waste of public money that characterise the political class—to announce the time and start each Live. He moves his hand to pick up his glasses and read notes published by the press, which are also part of the stage. At this point, he introduces the guests—ministers or secretaries of his government—who support him in the construction of his speech. There is a limited and controlled interactivity, which departs from the social networks’ commitment to a conversational, horizontal, and spontaneous environment.

As he comments on the agenda items selected by his team of advisors, we are struck by the characteristics of Bolsonaro’s non-verbal communication: he moves his hands frequently towards the camera, bringing them closer to the viewer and pointing his right index finger to defend an idea or argument; when making criticisms or verbal aggression, he opens his eyes and mouth exaggeratedly, and moves his head forward. These movements are synchronised with his tone of voice, which alters according to the subject matter. When it comes, for example, to attacks on the press or criticism of the left, the political leader raises his tone of voice while, at the same time, calming down and speaking more softly as he reports on positive actions carried out by his government. Laughter is also present, especially when he is ironic or praises his ministers.

The use of vulgar and informal language stands out, which is another element that brings Bolsonaro closer to the common citizen. Examples include shortening words and verbs and employing slang or colloquial expressions. In Video 2, when using an aggressive tone to accuse the PT of corruption, the president confesses that he uses swear words: “Then I said a swear word. There is no way!” (26’27”). In another context, to discredit the press, he says, “This here is a shot in the water! It’s embarrassing! Shame!” (Video 6, 29’18”).

Populism also differs from traditional political ideologies in that the leader does not represent but actually embodies “the people” (Moffit, 2016). In this sense, the vulgarity expressed by Bolsonaro is a central element of representation of the common man, with all the virtues that this would imply (sincerity, honesty, spontaneity, and a series of other moral values with respect to the professional politician).

“Brazil Above Everything, God Above Everyone”

In Brazilian social thought, the significance of relationships is like in countless other cultures. Messages, frequently used in the content disseminated on social networks by the far-right, often employ resources such as metaphors, which, according to Musolff (2016), provide an added pragmatic value to descriptions. Thus, complex ideas about human relationships are ordered as metaphorical narratives (Lakoff, 2002; Dekoninck & Schmuck, 2022).

Nevertheless, conservatism, a characteristic of the far-right, has different cultural expressions in the international context. In the case of Bolsonaro’s Lives, this is represented through religion, family, and the fatherland, embodied in the slogan used during his 2018 and 2022 election campaign: “Brazil above everything, God above everyone.” In this way, he manages to attract evangelical and Christian followers who “defend” the family and the fatherland.

The manifestation of the religious in his speech appears when he mentions the statements of PT senator Roberto Requião, who, according to Bolsonaro, mocked the name of God. The PT senator claimed that the land titles demanded by the Landless Workers Movement should only be granted if they were signed by God. To this, Bolsonaro responded: “A citizen like that, a guy like that is still mocking religions. He still uses the name of God in vain. There are humble people who need a piece of land to survive” (Video 7, 25’03”).

Religiosity is also associated with the defense of the family when criticizing the approval of abortion in Colombia, stating: “In other words, abortion now in Colombia was a Supreme Court decision. Colombia borders Venezuela up there. So, until the sixth month. We have information that it seems that there are people who are born at six months and survive. It is difficult, but they survive. So, here we have a crime” (Video 3, 10’37’’). In the same vein, Bolsonaro judges the PT’s family pattern as “crap” in Video 8, linking it to the liberation of abortion and the deconstruction of heteronormativity.

The discourse around God and the family, which underpins Bolsonaro’s conservatism, also draws on patriotism. In “Our Brazil is always above everything. Let us swear to lay down our lives for our fatherland and, if necessary, also for our freedom” (Video 7, 3’25”), the president links the idea that “Brazil is always above everything” with “swearing to lay down our life for the fatherland and our freedom.” It is worth noting that the defense of the homeland, in addition to being part of the speech, is present on the stage of the videos through the Brazilian flag positioned in the background or on the desk. This scenario is framed in an innovative digital environment, yet steeped in tradition and conventionalism to emulate the institutional.

From the perspective of the populist theory studied, this metaphor would be an example of how signifiers, such as the flag, the fatherland, or God, can be renamed and resignified. This process requires the construction of a collective subjectivity (Fischer et al., 2022), as in the case of Bolsonarism, which exceeds and transcends the current encyclopedia compendium of names (myths, narratives, symbolism, ideology).

Attacks Against Journalists and Political Opposition

Both the press and groups considered the opposition are seen as Bolsonaro’s enemies. As part of his performance in the Lives, he emphasizes his aversion towards the media and journalists. He tends to use press publications with two specific objectives: 1) to highlight the positive actions of his government and 2) to refute the news and attack the media and journalists when the content refers to investigations that question some aspect related to his administration. In this latter case, the accusations refer to the production of fake news by the press and criticism of journalistic work, like in the following statements: “(There’s) a bit of mistaken news here” (Video 5’, 6’25”) and “Fruit of investigative journalism? Investigative, not at all. A bunch of shameless journalists. They don’t investigate anything’ It’s fake news all the time” (Video 8, 21’53’’).

Criticism of the press also continues when discussing issues related to religiosity. In Video 6, the president reinforces the rejection of Christians and evangelicals towards the main Brazilian television channel that questioned the actions of the Bolsonaro government: “Some televisions like Globo, which always feels resentment towards evangelicals, towards Christ, and takes advantage of it to potentiate” (23’10”). In the same Live, he expresses his wish that the Public Ministry would investigate the publications of Folha de S.Paulo. After characterizing the journalistic work of this newspaper as “cowardly,” he states that: “I wanted the Public Ministry to investigate all the newspaper stories that are going around” (Video 6, 28’59”).

The Brazilian press is constantly under attack and only stops being so when it reports on positive aspects of the Bolsonaro administration. For example, the Jovem Pan channel was not attacked at all. This channel broadcasted Bolsonaro’s Lives and tripled its advertising income during the president’s term in office. This channel became the voice of Bolsonarism (Chaves et al., 2022; Soprana et al., 2022). Furthermore, in early January 2023 (just after the entry of the new Lula administration), the same channel received a complaint from the Public Ministry accusing it of producing and disseminating fake news (Feltrin, 2023).

Similarly, Bolsonaro employs an aggressive discourse toward the opposition represented by politicians affiliated with left-wing parties. Referring to the vote on the fake news legislative proposal in Video 8, the president states that he would not even have read such a proposal because the author is a member of the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB). In the statement: “So, as a rule, any project that comes from the Pt, PCdoB, and PSOL (Socialism and Freedom Party), you can vote against without reading. They rarely present a good project” (Video 8, 4’40’’), he normalizes the attack on the opposition by affirming that their projects of law are not relevant to the citizenry, accusing them, in this case, of “using the weapons of democracy to install socialism in Brazil.” In another fragment, he concludes by accusing the opposition political parties of installing censorship: “That is, they would be starting censorship in our country” (Video 8, 5’05’’).

Criticism of the PT, which has Lula as its greatest representative, is constant in Bolsonaro’s Lives, as seen, for example, in statements like the following: “The PT never cared about the people of the countryside. This talk of agrarian reform was just marketing” (Video 7, 4’45”) and “This is the government of the PT: just projects outside, all concluded and very well done” (Video 2, 31’06”).

By attacking the opposition and the press, Bolsonaro creates an ideal scenario to argue that the best channel for citizens to be well-informed is through his official accounts on social networks, where he can disseminate the information that suits him, without filters or mediation, and make use of populist elements by acting as a political influencer. With this operation, Bolsonaro would strengthen a frontier of political identification between an “us” and “them,” which would outline the identities of collectives and reinforce the concept of the enemy, in this case, the press and political opposition.

From the Use of Opinion Without References to Negationism

By discrediting the press and journalists, Bolsonaro has prepared the ground to express his views without using references. In this context, the president gives his opinion following the most representative ideas of the far-right without any sources or figures from research or studies. This is one of the scenarios propitious for generating political polarization and disinformation.

The speech below illustrates how he deals with topics related to the Covid-19 pandemic without including any scientific data: “I’ll give a tip to the scientists: in sub-Saharan Africa, it’s very common to have a disease called river blindness, and people take a little drug from the river to treat blindness. And there are also many cases of malaria. People take other drugs to fight malaria. These two medicines, which cost a pittance, by coincidence or not, there in Africa, also fought Covid” (Video 7, 15’19”). In this fragment, the president refers to a homemade medicine that, according to him, fought the virus in Africa.

Still on the pandemic, without presenting any scientific data, Bolsonaro states: “For young people, the chances of aggravating the virus is 0.0 or so” (Video 3, 16’27’’), reinforcing the idea that the probability of young people and children dying from the disease is practically nil, even though figures from the Butantan Institute indicate that almost 1,500 children up to the age of 11 died from Covid-19 in Brazil from the start of the pandemic until December 2021 (Portal do Butantan, 2022). On the same topic, in Video 9, the president insisted that vaccines against the virus were scientifically unproven, as were drugs discovered by chance (Video 9, 14’05’’).

It should be noted that assertions and opinions without including data, references, or sources cover other topics, such as corruption. Without presenting evidence, Bolsonaro implies in his Lives that there is only corruption in PT governments. Subsequently, he explains why there is no corruption in his administration—claiming that he is superior to other politicians: “Why is there no corruption in my government? We are one step ahead” (Video 6, 21’13”).

This type of opinion implies negationism, present in a fragment of Video 4, in which, when mentioning the criticism received from the press and international political leaders regarding the fires in Amazonia, he is assertive in denying, without any scientific data, that this area does not burn because it is humid: “Whoever says that the Amazon is on fire is lying. The Amazon is not on fire, the rainforest does not burn” (Video 4, 54’16’’). Something similar is observed when Bolsonaro states that the crisis in the economy is related to preventive isolation during the pandemic: “Why did the economy go down in 2020? Because of the irresponsible policy of staying at home. We’ll see the economy later” (Video 5, 12’22”), denying thus other dimensions in the economic crisis in Brazil.

Bolsonaro’s discourse in his Lives is also characterized by authoritarianism. The president presents himself as the bearer of truth in absolute terms. In the following fragment, he affirms that, despite not being a journalist, he transmits “good information” to the public: “I have no relation to journalism. My background is different: military and physical education. But I try to do my best and always transmit good information to all of you” (Video 5, 40’38”). In line with this statement, in several videos, the president invites his followers to get information through his official accounts on social networks, where they will find the most accurate information. Thus, he seeks to ensure that citizens receive disintermediated and biased information, minimizing the possibilities for them to have access to a plurality of voices and sources.

This case would represent one of the nodes that make up what we have defined in Laclau’s theory as the “chain of equivalence.” For Laclau (2005), each social force not only has its own singular, specific trajectory, social interest, forms of exploitation, and material wants but also its own point of difference. Bolsonaro could appeal to a negationist discourse that would not necessarily be endorsed by all his sympathisers but would build one more piece in the puzzle of ideas, ultimately consumed as a specific worldview capable of articulating apparently contradictory views. Under the chain of equivalence, these differences are retained and respected, given that they are organised to gravitate around the agenda of equivalence.

The chain of equivalence creates an intersection between these social forces and factions only through the points being interpellated via the emblem or symbol, in this case, the political and journalistic lie, capable of deceiving citizens about the reality of Covid-19 or the “fake deforestation” of the Amazon.

DISCUSSION

The figure of Bolsonaro as a political influencer combines several elements of “digital populism” (Gerbaudo, 2018; Cesarino, 2020) or other subtypes of populism represented by what is called the “pop far-right” (Goldstein, 2019), including the use of vulgar language, the use of informal clothing and accessories, and the presence of the Brazilian flag in the video scenarios (Gallardo, 2018). In this way, he resembles the common man and, consequently, promotes a greater closeness of the political leader to the people who, at times, also identify with his actions and government proposals.

These elements also serve as a basis for constructing a discursive line that relies on conservative values around religion, the fatherland, and the family to promote attacks on the press and the opposition. These attacks on the media and journalism represent the discrediting of the Brazilian press by the president, which weakens the reputation of these institutions in the eyes of public opinion and indirectly influences the democratic process.

In the case of opposition parties, the main objective is to disqualify their actions and favour ideological extremism. The context of the attacks and extremist speeches of the former president, filled with dramatization and exaltation of the character (Laclau, 2005; Mouffe, 2005), contributes to the construction of a scenario in which subjectivity and symbolism sustain the figure of the influencer Bolsonaro.

In addition to disparaging the media, journalists, and opposition figures, Bolsonaro insists on expressing opinions without referencing scientific data or sources. In this case, his negationism on issues such as the Covid-19 pandemic or the economic crisis is one more element that forms part of his strategy as an influencer to generate political polarization (Colussi, 2020). Hence, the figure of the Brazilian president as a political influencer becomes an agent favouring political polarization, which represents a threat to democracy (Pérez, 2022).

CONCLUSIONS

After carrying out this qualitative research based on a methodological triangulation established for the analysis of different elements that constitute Bolsonaro’s discourse in the pre-election period of 2022, it is observed that the then-president relied on the authority of his position to provide truth to what he transmitted in his weekly Lives from his Instagram account. His discourse achieved self-legitimation in a protected environment, in which the president acted as presenter and communicator, trying to impose his truth as the only valid way of understanding the country’s reality.

In this performative universe created by the then-president of Brazil, the stage has been one of the key aspects to consolidating his image as a political leader and influencer. There is a continuous attempt to connect with citizens and seek their identification through a careful choice of clothing, accessories, stage composition, gestures, looks, laughter, eloquent and intentional pauses, and the employment of a much plainer language than what could be expected of a government president.

Considering elements of the populist theory, such as chains of equivalence, the construction of antagonism, and empty signifiers, they are particularly useful for understanding, as demonstrated through the study, how a “Bolsonarist folk” is constructed, born out of the very process of political and social polarization.

These concepts can also be studied from the metaphorical frameworks we have pointed out, given that staging is constructed through symbolic metaphors that accentuate opposing positions: 1) the metaphor of simplicity, which establishes an antagonistic boundary for the common man, who represents the people based on a confidence-inspiring folksiness (the idea of an “us”), and 2) the metaphor of perversion, in a chain of equivalence represented by the left and the media, which seeks to deceive and manipulate (the idea of the other as guilty and enemy). These populist techniques, in line with Laclau (2005) and Laclau & Mouffe (2004), will be a constant in the way in which Bolsonaro addresses the audience.

By supposedly speaking with sincerity, claiming the validity of his opinion over contrasted information or even scientific studies, Bolsonaro is entering emotional grounds that hinder critical thinking and encourage an explosive and thoughtless reaction on the receiver’s part. In this sense, the tension, extremism, and polarization experienced by the Latin American country may have emerged as the effect of a communicative strategy developed according to the symbolic precepts of digital populism.

The above is one of the hypotheses that emerge from the results of this analysis. This premise would reinforce the existence of a probable positive correlation between disintermediated cyberpolitics, constructed based on a subjective and metaphorical narrative, the advance of extreme ideologies, and political polarization, aspects that can undermine democratic processes. The discursive model propagated by the former Brazilian leader promotes a form of communication with authoritarian traits that manage to camouflage it in the interactive properties of the chosen media environment—social networks. This interactivity is never fully established due to two fundamental issues: the configuration of the president as the only reliable source of information, which eliminates in advance any possibility of dialogue, and the authority of his figure as supreme governor, highlighting the asymmetry of power relations.

Finally, it is observed that the circulation of these videos seems to have played a fundamental role not only during the electoral campaign but also in the construction and maintenance of government ideals. The study of the reach of these videos and their effects on the audience could lead to validating a hypothesis based on the influence of a symbolic and ideological discourse on voter decision-making at the polls