INTRODUCTION

This is an essay, the thing and the action. In this article I attempt to bring together several different ideas into a single picture. My goal is to propose, and try to explain, a simple puzzle: despite the enormous costs and human suffering it creates, violence is often irresistible and many countries exhibit episodes of civil war or protracted internal conflict. In the process, I propose a political economy of conflict and state building, with messages that apply beyond Colombia. The ideas come mostly from my own research projects (with several collaborators!).1

To begin, consider some numbers from this conflict-ridden country, with a population of about 48 million. Over the last 37 years, the national registry of victims counts almost 8 million direct victims from the conflict. Of these, almost 11,000 have suffered from landmine explosions and close to 6.9 million have been forcefully displaced. Estimates of minors recruited by armed groups reach about 8,000.2 From 1958 to 2012, the Grupo de MemoriaHistórica (2013, pg. 50), an autonomous group commissioned by the government to compile the history of victims of violence in Colombia, estimates that 220,000 died as a result of armed conflict, 81% of them civilians. It also reports: 27,023 cases of kidnappings (including 318 municipal mayors, 332 local councilors, 52 departmental assembly members and 54 congressmen), 16,000 of them occurring between 1996 and 2002; 8.3 million hectares (20.5 million acres) and 350,000 plots abandoned or stolen; about 300,000 people displaced each year from 1996 to 2002. A partial list identifies close to 1,600 members of a single political party killed (Ospina, 2012).

You would think that a country suffering this much from violence would try really hard to solve it. Not necessarily. The main argument I propose is that there are many reasons why several politically relevant sectors in Colombia encouraged, embraced, or at least did little to change this violence.

At a superficial level, this argument may be almost evident to some. One could say that the Colombian conflict was for years "elite friendly". Politically powerful groups in Colombia have been able to cope quite well with the conflict, and it is the relatively poor and under-represented who have carried the burden of the costs. An old common saying in Colombia is el país va mal, pero la economía va bien (the country is doing poorly, but the economy is doing well). For decades, the country faced a low, intensity war that was not too disruptive of the main economic activities and investments of the economic elites, and for big parts of urban Colombia conflict represented a nuance, serious at times, but not a catastrophic problem. Consistent with this idea, when the problems have become more serious the country has gotten its act together (to some extent) and found solutions. For instance, the first large peace process with left-wing guerillas occurred with the M-19, a guerilla group more closely related to urban areas, more visible and therefore possibly more threatening to elites. The 'false positives' phenomenon which I discuss below only became truly problematic when it occurred near the capital city of Bogotá. Even the large military investments in military action against the guerilla initiated by the Pastrana administration and followed by Uribe's Seguridad Democrática (Democratic Security) policy started only when the guerilla groups became so powerful that they were a true threat to average citizens and urban centers.

But this essay will argue that the problem with Colombia (and other conflict-ridden countries) is that conflict can be elite friendly in a more fundamental way. Persistent conflict is hard to solve because there are politically strong groups that benefit from it directly, or at least from an organization of society in which violence is a side effect. I will discuss three broad sets of problems. I will call them: the public goods trap, rents from disorder and the many dimensions problem, and the vicious circle of clientelism and state weakness. To get there, I first briefly define the twin problem of persistent conflict: state weakness. I then offer my main set of arguments. Finally, I conclude with some ways forward and searching reasons for optimism.

THE STATE

A political economy of state-building is the flip side of the coin of a political economy of conflict. This claim pushes us to define what a capable state is.3 The discussion (especially among academics) could take us very far from the purpose of this essay. However, I only need the reader to agree on the following.

First, a capable state ideally should provide public goods to broad cross sections of the population. Particularly salient is the provision of security and order. In fact, more than salient it is defining for many scholars at least since Max Weber famously described the state as "a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory" (Weber, 1919[1946 edition]).

Second, "legitimate" is an important word here. While there may be several sources and definitions of legitimacy (that discussion would be even longer!), in democracies one can think of legitimacy as stemming from the ability of ordinary citizens to control the state and prevent it from abusing its power. As Levinson (2014) puts it, this ideal type of state solves the fundamental dilemma of state power (that "a state that is powerful enough to deliver valuable goods is also powerful enough to inflict great harms" (p. 183)) by making power and control complements: because citizens can control the state, they are willing to vest it with more power. Following Acemoglu (2005) one can also call this a "consensually strong state", simply because it becomes stronger with the consent of citizens.4

If we can agree on this, then we can also make progress on our original question (who wants violence?) with the following: who opposes a consensually strong state? In certain contexts, many people do. I will now suggest three broad groups of inter-related "mechanisms". These three sets of reasons help explain why a consensually weak state and persistent conflict are so prevalent, not just in Colombia, but also in other societies. In fact, when discussing each mechanism, we will observe the types of social features that help these mechanisms flourish.

THREE PROBLEMS

The public goods trap

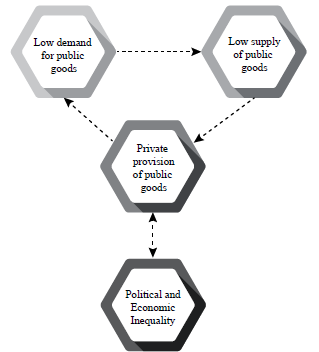

The public goods trap is illustrated in Figure 1. Start in any box in the cycle. For instance, with low supply of public goods. Whenever public goods are poorly provided in a society, people find ways to satisfy their needs. If they have the resources, they will try to privately provide for themselves what the government fails to offer. This explains the arrow connecting "Low supply of public goods" with "Private provision of public goods". But now think of the implications. If people have their needs satisfied privately, if they have solved the problem, they do not need to demand public goods. Hence the arrow connecting "Private provision of public goods" with "Low demand of public goods". The final step in this feedback loop simply recognizes that when people do not demand public goods from the state, the state will not provide as many of them: from "Low demand of public goods" to "Low supply of public goods". Full circle.5 These connections reinforce themselves and prevent the state from doing one essential thing it ought to do: provide public goods to broad cross sections of society.

Notice also how this rests on, and reinforces, economic and political inequality. It reinforces economic inequality because when some essential goods are not publicly provided and citizens must make up for these shortages, the well-off can do it but many poor individuals may just have to do without them. This widens the gap in access to essential services. The rich, who are often the more influential and could arguably more effectively demand action from the state to solve the problem, are not really that preoccupied. Moreover, in unequal societies with cheap labor, it will be particularly easy for the rich to get these essential goods, and particularly difficult for the poor to obtain them. Economic inequality therefore sustains, and is a by-product, of the public goods trap.

In addition to economic inequality, political inequality more fundamentally feeds into and reproduces the public goods trap. It is more fundamental because the trap would collapse if one imagines a situation of extreme economic inequality, but with perfect political equality. If all voices are heard equally loudly by the political system (in other words, if there is political equality) excluded groups who cannot privately provide for the essential services will be heard. Public goods will be provided to them, and the negative feedback loop will turn into a positive one. Otherwise, political inequality is reproduced by the public goods trap: the large gaps in access to essential services, and resulting gaps in economic conditions, weakens the poorer individuals on many dimensions, among them their political clout to achieve change.

This view resonates with that in Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2005), which not only emphasizes the role of institutions as fundamental determinants of the economic and social performance of societies, but gives political power and institutions an even more fundamental role than economic power and institutions. Indeed, and as some of the mechanisms discussed below will reveal further, the distribution of political power is a more important determinant of the organization of society and can have larger and more persistent effects.

It is easier to think of the public goods trap with some concrete examples. In Colombia, public schooling is widely available in the basic levels, but it is on average of very poor quality. There is a poor provision of this public good. Families who can afford it therefore opt out of the system and provide a private education for their children. Data from a large panel survey conducted by Universidad de los Andes (Encuesta Longitudinal Colombiana de la Universidad de los Andes,Bernal et al. (2014)) indicates that in the poorest households about 9 out of every 10 children attending school go to a public institution.6 For the relatively well-off, the ratio is reversed, and 9 out of 10 are in private schools.7 This tends to decrease the sense of urgency, especially among the richest sectors of society who often have a stronger political influence, in improving the quality of public education.

A more essential example is of course security. Security guards in apartment buildings are the rule in Colombia. Gated communities are also common. But people living on slums depend on whatever public security the city provides (or fails to provide). More perniciously, part of the reason for the emergence of paramilitary groups in Colombia was the failure of the state to provide law and order in various areas of the country. Groups of landowners, many of them also drug traffickers, decided to provide that for themselves by forming private armies. But this left others vulnerable to violence in general and to paramilitaries in particular, reinforcing the disparities and the state's failure at monopolizing legitimate violence.

Paramilitaries are perhaps the most extreme manifestation of the public goods trap. But the public good trap permeates other dimensions, even creating a "paramilitary culture" with negative consequences for the consolidation of peace and a capable state. This could be another reason, together with the clientelistic nature of politics that I discuss below, for the very fragmented nature of Colombian society where individuals compete against one another, lack a common purpose, and instead try to fend for themselves as best as they can. Some, like Thoumi (2002) attribute that phenomenon to the geographic characteristics of the country, which creates obstacles to the state's capacity to control the territory as well as obstructs the creation of national community and solidarity. Others claim that part of the origin for this individualistic tendency is our Spanish heritage (García-Villegas, 2017). The public goods trap can also create, or exacerbate, a set of social norms consistent with these views.

The public goods trap also offers a simple conjecture for one of the most commented features of Colombia's macroeconomic history: its exceptional stability (Robinson, 2007). We can think of "macroeconomic stability" as the one public good that Colombia has provided quite effectively, at least compared to its neighbors and compared to other public goods in the country. And there is indeed one special aspect of this public good: it cannot be provided privately. Setting up a high quality private school is one thing elites can do without the state functioning properly. Avoiding a volatile exchange rate, hyperinflation, or unsustainable fiscal policies, not. Elites are thus more naturally preoccupied with making sure the economy is handled responsibly than with public schools providing high-quality education. They can substitute the latter privately, not the former. And this may be, in addition, another reason why some may oppose peace building efforts. These efforts typically require important social transformations, that may produce a fiscal burden and times of uncertainty. Elites may dislike this more than the casual discomfort from violence and insecurity, from which they can largely protect themselves. But also conversely, perhaps if and when the weak state becomes incompatible with macroeconomic stability, Colombia might also consolidate some minimal state capacities. Consistent with this, the history of the "wealth tax" in Colombia reveals that the elites agreed to be taxed only when they perceived high risk of "losing it all" with a severe security crisis (Rodriguez-Franco, 2016).

The public goods trap, therefore, present in countries with poor economic and political institutions, is part of the reason why internal conflict may be so persistent and the efforts to build more capable states so shy and unsuccessful.

RENTS FROM DISORDER AND THE MANY DIMENSIONS PROBLEM

The trouble with rents, especially political

Perhaps an easier explanation to why people want violence is that there are groups that derive economic rents from war. Some are obvious, like the arms industry. Or the leaders of illegal economies (drugs, illegal mining, smuggling), who enforce contracts with brute force, prefer a weak and corruptible state, and are better off when violence dictates who gets what. Others are less so. Even legal companies may prefer a conflict-ridden country to operate, if this provides barriers to entry to competitors or a lax regulatory environment in terms of regulation. Guidolin and La Ferrara (2007) show this persuasively for the diamond industry in Angola, and it is not hard to recognize similar dynamics in other countries, including Colombia.

This is indeed one important reason. But it is not the whole story, and I would argue not the most important. Just like political inequality is more fundamental than economic inequality in the public goods trap, political rents are more fundamental in explaining who wants violence. One reason has been noted already: politically powerful people shape society more directly than economically powerful people. A complementary argument is that economic elites, whose rents depend on the profitability of their investments, often suffer directly from the disorder and inefficiencies that a poor provision of public goods entails. They may therefore promote efficiency-enhancing reforms, including strengthening the capacity of the state to provide public goods; at the very least, there might be a limit in the extent of disorder that they would like to tolerate even when it brings other benefits like barriers to entry or weak regulation and little oversight. Instead, political elites may be less interested in efficiency-enhancing reforms if these reforms can weaken their control of political power (Acemoglu, 2003).

Of course, economically powerful people tend to have political power too, but the coincidence is not perfect (and at least conceptually the distinction can be made). In fact, for early XXth Century Colombia, we show in Chaves, Fergusson, and Robinson (2015) that the prevalence of electoral fraud is particularly high where economic and political elites coincide or overlap. Moreover, the strength of economic elites as captured by asset inequality is associated with less, not more fraud. These correlations are consistent with economic elites suffering from the disorder of a weak state and prevalent fraud around elections (often turning violent), whereas political elites are more willing to embrace the disorder because it allows them to retain power.

Acemoglu, Robinson, and Santos (2013) study the case of "parapoliticians" in Colombia, a perfect illustration of this problem. Parapoliticians are politicians who made deals with paramilitaries to influence elections. These authors show that since the paramilitary groups formed an umbrella organization (the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, AUC) and got more actively involved in politics, the presence of paramilitaries in a municipality is correlated with the rise of parties associated with the paramilitaries. Their data also reveals that when a senator's list receives more votes in areas with high paramilitary presence, the senator is more likely to support policies benefitting the paramilitaries (specifically, key favorable legislation in the context of a peace process with these groups). Moreover, paramilitaries tend to persist where they appear to have delivered votes to their preferred (and ultimately winning) Presidential candidate. All of these findings are consistent with a simple theory where politicians have very limited incentives to consolidate the monopoly of violence in some areas of the country because this displaces the paramilitaries who influence elections in their favor.

The case of parapoliticians, similar in other countries where crime and politics gets intertwined,8 shows one way in which some may oppose ending conflict for fear of losing an electoral advantage and political power. Another reason is that politicians often like "enemies" in conflict, and therefore have a vested interest in not ending the conflict. In an article titled "The need for enemies" (Fergusson, Robinson, Torvik, & Vargas, 2016) we develop and test such an argument. Our theory goes beyond the well-known "rally around the flag" effects that occur when a country is facing an external threat (US presidential ratings, for instance, typically go up after terrorist attacks). Instead, we emphasize the urge of politicians to make themselves needed. This phenomenon is familiar outside politics. If you hire someone to work until a particular task is completed (say, you hire an auto mechanic to solve some annoying noise in your car's engine), then by completing the task the person is putting himself out of a job. The same can happen in politics when some politicians are elected because "they are the person for the job". Winston Churchill, for instance, was thought to be the one for the job to lead Britain to victory in the Second World War. As soon as the war was won, British voters removed him from offce.

Perhaps nothing explains better the essence of our argument than this unusually candid declaration of former US congressman Newt Gringrich in 2008:9

This is, by the way, the great... one of the great tragedies of the Bush administration: the more successful they've been at intercepting and stopping bad guys, the less proof there is that we're in danger. And therefore the better they have done at making sure that there is not an attack, the easier it is to say 'well there was not going to be an attack anyway.' It's almost like they should every once in a while have allowed an attack to get through just to remind us.

In Fergusson et al. (2016) we develop a theoretical model capturing this logic: when some politicians are perceived as having an advantage in the military fight against insurgents, they want the fight to persist. The main prediction is that large defeats for the insurgents reduce the probability that these politicians fight them, especially in electorally salient places. Consistent with this, we find that after the largest victories against Farc rebels in Colombia, the government reduced its counterinsurgency efforts, especially in politically important municipalities. These patterns suggest that politicians sometimes need to keep enemies alive in order to maintain their political advantage. They behave like the auto mechanic who refuses to end the task once and for all. This, of course, is not good news for peace and state building.

The need for enemies and the case of parapoliticians highlight how protecting political power can be a strong determinant of persistent conflict and failure to build a functioning state. A further problem arises when certain groups can exert violence as a result of political developments that hurt their interests. This is an issue we examine in "The real winner's curse" (Fergusson, Querubín, Ruiz, & Vargas, in press).10

In many countries, despite the presence of nominally democratic institutions that should provide the type of citizen control that a consensually strong state needs, some political groups remain largely excluded from formal political power. De facto barriers can take different forms and, in the extreme, outright violence is used. In the case of Colombia, following a legacy of power-sharing agreements between the Liberal and Conservative parties, local elections were introduced in the late 1980s to open up the political system and broaden access to power to formerly excluded groups. A new constitution enacted in 1991 further opened the political arena. Noteworthy among the new entrants was the left, poorly represented by traditional parties, and opposing some established powerful groups like the landowning elites with ties to the paramilitaries. Indeed, these new political actors began advocating different policies than those of traditional parties, including a stronger emphasis on redistribution, communal property rights, land reform, and vindication of peasant rights. Some were able to win local offce.

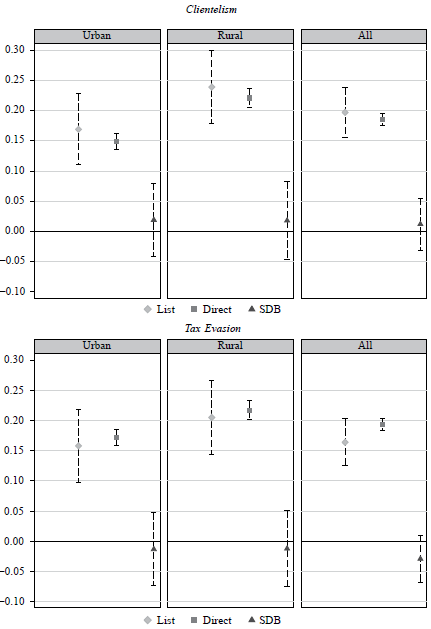

To study the effect of left-wing victories, we use a regression discontinuity design (RDD) based on close elections and compare municipalities in which the left narrowly won versus narrowly lost the mayoral race. Our results, illustrated in Figure 2, show that a narrow left-wing victory increases right-wing paramilitary violence during the subsequent government term. Also, these effects are concentrated at the beginning of the term and close to the subsequent election. These patterns, together with a comprehensive analysis of all the perpetrated attacks and the evaluation of the left's subsequent performance in elections, points at a concerted effort to intimidate left-wing political leaders to limit their actions in office, disincentivize them from running again, and coercing voters to vote for other options.

Source: Fergusson, Querubín, et al. (in press).

Figure 2 Effect of electing a left-leaning mayor on paramilitary attacks

In the same spirit of these findings that the introduction of democratic reforms produced unexpected consequences, Steele (2011, 2017) shows that elections in Colombia have helped armed groups identify local cleavages and "disloyal" residents, provoking violence against them.

A curse of dimensionality?

The real winner's curse highlights other difficulties to build a (consensual) state. Indeed, the reforms introduced in the late 1980s and early 1990s to increase political representation of outsiders and strengthen local democracy at first sight constitute real efforts to build a consensual democratic state, and they may have played this role too. But a capable state must be strong on many dimensions. When one dimension becomes stronger (in this case, local democracy) but others remain weak (security and order was not yet guaranteed in the territory), politically powerful groups can take advantage of the weak spots to accommodate and counteract the state-building efforts.11 In this instance, it is clear that the politically powerful took advantage of the weak spot to undo the improvement the central government had achieved and to establish something more closely resembling a local authoritarian regime than a local democracy.

This discussion underlines that one of the reasons why it is so difficult to build a capable, consensual state, is that many things have to work well at the same time. Many dimensions have to be strong or else the whole apparatus may be as resilient as its weakest spot. Another example of this comes from parapoliticians and their exposure in the media, an issue we study in Fergusson, Vargas, and Vela (2013). The most optimistic view of the media give it an almost determinant capacity to ensure accountability in democracies. Thomas Jefferson went so far as to say:

The functionaries of every government have propensities to command at will the liberty and property of their constituents. There is no safe deposit for these but with the people themselves, nor can they be safe with them without information. Where the press is free, and every man able to read, all is safe. (Thomas Jefferson to Charles Yancey, 6 January 1816. Emphasis added).12

Yet, our work on media exposure of Colombian parapoliticians suggests that unless free media operate in a sufficiently strong institutional environment, provision of information about politicians' misdoings may not increase political accountability and may even have unintended negative consequences. In particular, exposure of misdeeds can lead politicians to double-down on misdoings where they have that option still available. A simple theory in which corrupt politicians can decide how much effort to invest in coercion (with paramilitaries' help) predicts that media exposure, while decreasing average popularity relative to his opponent across all districts, increases incentives to invest in coercion. Hence, the media scandal may increase the vote share of the exposed politician in places where, by increasing coercion, he fully compensates for the popularity loss. If this effect is strong enough, the media scandal may not hurt the overall electoral success of the exposed politician.

The data fit these predictions. Parapoliticians exposed by the press before the elections shift their distribution of votes to areas in which coercion is easier to exert (areas with more paramilitary presence and less presence and efficiency of state institutions). This reshuffling of support is sufficient to compensate the media scandal, and their total vote share does not significantly diffier from that of unexposed candidates. The media scandal had clear negative unintended consequences: it increased coercion and did not stop corrupt politicians from being elected. This again highlights the complementarity between different dimensions of well functioning state. A free and active media needs, also, the existence of free and fair elections.

Eaton (2006) studies another case where an otherwise positive reform for consolidating a more responsive state created unintended negative results given the absence of complementary institutions. Namely, he argues that fiscal decentralization (which could help bring policy closer to the interested constituents) exacerbated internal conflict because it in fact financed the expansion of "armed" clientelism by illegal groups. That is, given the weakness of the armed forces in much of the territory, guerrillas and paramilitaries used decentralized resources to destabilize the state, limiting even further its monopoly over the use of force.

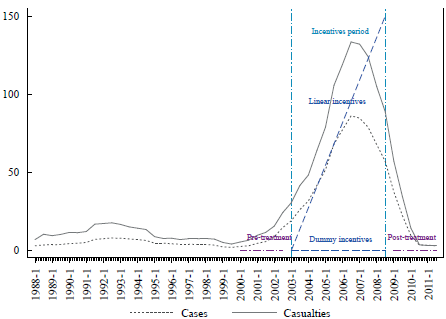

Another example comes from the (very inaptly named) phenomenon of "false positives" in Colombia: the killing of civilians by the armed forces to present them as if they were guerilla members killed in combat. In Acemoglu, Fergusson, Robinson, Romero, and Vargas (in press) we study this problem. The dramatic increase in these cases is illustrated in Figure 3. The increase occurred following a policy of stren-gthening the military and its incentives to combat the guerilla after President Uribe came to office in 2002. In an effort to regain the monopoly of violence, the army was given more resources to fight insurgents and a system pushing for results, involving both formal and informal incentives, was introduced. A special UN commission investigating the case after a scandal broke in 2008, concluded that:

Source: Acemoglu et al. (in press).

Figure 3 False Positives. by Semester Cases and casualties 1988 -2011

There were incentives: an informal incentive system for soldiers to kill, and a formal one for civilians who provided information leading to the capture or killing of guerillas. The ... system lacked oversight and accountability. (Alston, 2008, p. 2)

The data we present in Acemoglu et al. (in press) reveals, not just that a large upsurge in illegal murders of civilians coincided with the policy, but that this happened more where military units were headed by colonels, who have stronger promotion incentives, and where local judicial institutions were less capable of investigating killings of innocent civilians. We also found that, during this period, the efficiency of judicial institutions further deteriorated where brigades were led by colonels. Finally, the policy does not even appear to have contained guerilla and paramilitary attacks.

In short, an effort to regain the state's monopoly of violence again backfired and had limited success because the appropriate checks on military misconduct were not correspondingly robust. A key explanation for the (unintended) consequences of the effort was the failure to understand the fundamental complementarity of state institutions and the importance of investing in the many dimensions of the state.

The many dimensions problem (exemplified by the real winner's curse, the parapoliticians' media scandal, the false positives, and decentralization) reveals that, often, the problem is not simply that the state is not strong or capable enough. Rather, that it is unevenly strong or unevenly capable. The dimensions along which the capacity of the state may vary are many, as these examples have revealed. A crucial one is the regional or territorial dimension. This dimension is implicit in some of the phenomena already examined (for example, left-wing candidates and sympathizers are disproportionally targeted in some areas of the country, paramilitary coercion occurs in some municipalities more than others). But I have not discussed some of the more direct consequences of an uneven capacity of the state in the territory.

In Fergusson, Molina, Robinson, and Vargas (2017) we focus on this dimension, by examining long-run regional patterns of development in Colombia. There, we argue that the diverging patterns of economic prosperity within regions in the country reflects correspondingly diverging qualities of economic and political institutions. More fundamentally, the areas with better-functioning economic and political institutions are the same places where the state has been more present and capable, with a remarkable persistence. Why has this (uneven) weakness been so persistent? We advance some hypotheses. Some are related to the interests of local post-colonial elites. Building a modern state may be advantageous from a social point of view, but the weak state allowed them to go untaxed and unregulated, and to manipulate the legal system to their advantage. Also, historically regional elites were worried about potential state-building projects, so much so that in the federal period laws were passed (Law 20 of 1867) to almost codify this by forbidding the national state to intervene in armed conflicts in its constituent states (thus legislating away the monopoly of violence). To enforce the equilibrium, rebellion was treated very softly (Fergusson, Mejíia, & Robinson, 2017).

There are further consequences of the territorial dimension: a weaker state in some areas than others, and the resulting relationship between national and local elites. This only exacerbates the set of obstacles to building a capable state. I do not delve into these issues in detail because Robinson (2013, 2015) offers an excellent discussion of a number of mechanisms along these lines. González (2014) also proposes an interesting perspective on the uneven strength of the state within the territory. Several other researchers have emphasized the importance of the territorial dimension, in particular the idea that the unevenness in the territorial reach and capacity of the state is a feature, not a bug (O'Donnell, 1993; Boone, 2012; Giraudy & Luna, 2017; Steinberg, 2018). That is, it is not that states cannot reach certain areas of a territory with their capacity to deliver public goods and order, but that they do not want to do it. Prominent among the reasons why they may choose this are different political incentives of the involved actors (citizens, local power-holders, and national politicians and the state). This is also a common topic in the "subnational authoritarianism" literature (e.g. Gibson, 2005, 2014; Giraudy, 2010; Sidel, 2014).

The uneven strength of the Colombian state also facilitated a very clientelistic form of politics. I turn to this issue in the next section, addressing the interplay between clientelism and state weakness.

THE VICIOUS CIRCLE OF CLIENTELISM AND STATE WEAKNESS

Clientelism, or the exchange of targeted benefits for political support, is another key reason for the persistence of a weak state. In fact, in Fergusson, Molina, and Robinson (2017) we argue, and show evidence from Colombia and other countries, that clientelism and state weakness are trapped in a vicious circle: clientelism weakens the state, and a weak state is the perfect environment for clientelism to flourish.

To explain this circle, we first clarify what clientelism is (and is not). First, we emphasize the particularistic and targeted nature of benefits: they are delivered to a political supporter or his inner circle, and can be given to supporters and withdrawn from opponents. Second, there is a clear quid-pro-quo: transfers and benefits are given in exchange for political support.13 Third, clientelistic political transactions occur at many levels: when a voter receives a gift in exchange for his vote, or when a contractor supports a politician and is then favored in exchange with a public contract awarded irregularly, or when the executive buys a senator's vote to pass some legislation by giving him some targeted benefit. Often these levels of exchange are interconnected (for example, the corrupt politician giving out contracts in a clientelistic fashion also buys votes in the election).

In our work, we capture clientelism by measuring clientelistic vote-buying. But this discussion helps emphasize that we do it not because it is the only relevant level nor the most damaging, as clientelistic transactions "higher up in the food chain" may in fact be the more crucial origins of the network of transactions. The motivation is that vote-buying is comparatively easier to measure than other types of clientelism. Specifically, it can be measured in surveys, it is a very concrete form of exchange, and it is likely to be interpreted equally by all respondents.

To measure the (consensual) weakness of the state, we rely on tax evasion.14 Tax evasion is a good indicator of the state's enforcement ability and its capacity to mobilize resources. But more importantly for us, it is also influenced by citizen trust in the state and their consent with the implicit social contract.

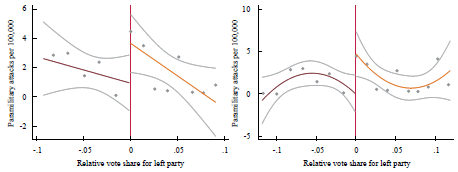

Yet measuring clientelistic vote buying and tax evasion presents several important challenges. Most notably, people may be ashamed to admit to these behaviors. To overcome these issues, we implement a survey method known as "list experiments" in the Politics Module (Fergusson & Riaño, 2014) of the Encuesta Longitudinal Colombiana de la Universidad de los Andes (Bernal et al., 2014).15

Intuitively, the method works by asking respondents about their behaviors indirectly, avoiding feelings of shame contaminating the responses. Respondents are divided randomly into groups, and some (the treatment group) are asked for how many factors, yet not which, they have taken into account when deciding who to vote for. Included in the list of factors are the benefits that the candidate offered in exchange for the vote (i.e., vote buying). Since the respondent is not revealing his specific behavior with his answer, shame should not bias his responses.

How does the researcher infer, however, the incidence of vote buying? Because another group of randomly selected respondents (the control group) are asked exactly the same question except that vote buying is no longer in the list of relevant factors. Since the two questions and respondents are otherwise ex-ante identical, any difference between the answers must be the incidence of vote buying.16

To infer tax evasion, a similar procedure is followed. Households are asked for how many actions they follow to save money when shopping. A treatment group gets evading the VAT tax as one of the options, and a control group not. The difference in average incidence for each group is the average incidence of evasion.

In addition to doing the list experiments to infer clientelism and tax evasion, we also asked directly to a third randomly selected group of respondents about these behaviors. Doing so provides an interesting contrast, as it allows us to compare citizen responses when confronted directly and when their response does not expose them. Any difference in the answers therefore captures how ashamed they are to honestly admit to clientelistic vote buying and tax evasion.

Figure 4 shows that there is no significant difference between the answers to these direct questions and the list-based estimates. This is the case both for clientelism (upper panel) and tax evasion (lower panel), and for rural or urban areas considered independently. This result is important and underscores how widely accepted clientelism and tax evasion are as part of the normal state of things, consistent with our view that the practices mutually reinforce each other and get deeply embedded in society.

A second key result in Fergusson, Molina, and Robinson (2017) consistent with the vicious circle is the existence of a very robust positive correlation between the two phenomena: people more likely to report evading taxes are also more likely to sell their vote. Indeed, while based on questions not dealing with potential reporting biases, the same correlation is also apparent in a sample of African and Asian countries included in the Afro-and Asianbarometer surveys.

So far this tells us that both phenomena, clientelism and tax evasion, are broadly considered normal and seem to be interrelated. But why? Which mechanisms tie the two behaviors together? We posit seven mechanisms or "sins". I now briefly discuss each one in turn, without delving into complementary empirical evidence provided in Fergusson, Molina, and Robinson (2017):

1. Preserving clientelistic parties comparative advantage.

A consensually strong state must provide public goods effectively to the population. Clientelistic politicians oppose this because it erodes their electoral advantage, which is delivering targeted, particularistic goods. Evidence from this comes not only from Colombia. With Horacio Larreguy and Juan Felipe Riaño, we study perhaps one of the most stereotypical cli-entelistic parties in Latin America: the PRI in Mexico (Fergusson, Larreguy, & Riaño, 2015). We find that when the PRI first got challenged by opposition groups in the 1960s, it reacted by manipulating the location of agrarian communities, sending them to distant locations (especially in municipalities where it faced more competition) to strategically increase the future cost of public good delivery. This compromised future local state capacity to provide public goods and services, and reinforced the equilibrium by leaving voters poor and dependent of the clientelistic relationship.

2. Personal over institutional links: displacing formal relationships with the state.

Clientelism relies on personal interactions, informal pacts and deals that can displace potential formal relationships with the state to demand rights and services. In an extreme case, the state does not exist as an apparatus to be controlled by citizens as in the ideal complementary relation between control and power. And to the extent that clientelism is effective at displacing formal connections, voters become more dependent on the clientelistic network for benefits, producing the vicious circle of more clientelism, less state capacity, and more clientelism, and so on.

The displacement of institutional connections with the state is therefore another threat to building a consensually strong state. Personalistic relationships of this sort are sustained by feelings of reciprocity. This is also problematic because they make clientelism very resilient. Specifically, cli-entelism will not necessarily disappear with simple institutional innovations as the secret ballot (e.g. Wantchekon, 2003; Vicente, 2014). As Lawson and Greene (2014) put it, "curbing clientelism requires a normative component-specifically, that citizens must reject clientelist exchanges on principle because they feel a greater obligation to vote in accordance with their conscience, obey the law, and support democratic institutions."

3. Personal over institutional links: fragmenting society.

Clientelism also contributes to society's fragmentation: each fragmented voter seeks some specific benefit from politicians or their brokers. A fragmented society of this kind, in turn, may also be more easily captured with targeted transfers, and fragmentation weakens collective action and political control over the state. Rather than control and capacity increasing in a symbiotic relationship, we see the opposite: citizens have less control over the state and therefore grant it less power. Each one minds its own business, a culture we had already encountered when discussing the public goods trap.

4. Breaking the social contract: mutual justification on defaulting.

When the politician pays for the citizen's vote, the voter infers that the politician is breaking his part of the deal and deriving personal rents from power. In turn, the politician's default might justify the citizen's decision to break his obligations, like paying taxes. Moreover, when citizens do not pay taxes and break the law, they have no stakes in defending the social contract and controlling politicians and the state. This again consolidates the consensually weak state and prevalent clientelism.

García-Villegas (2009, 2017) argues that this is particularly the case in Latin America, where following a Hispanic heritage the law is interpreted as stemming from a "pact" between "equals". According to this "pactist" tradition, when one side defaults the other has the right to default as well. The law (unlike religion or morals) does not hold a higher status than the individual. These mutual justification between politicians and citizens can also have negative spillovers between citizens. Indeed, a law-abiding citizen may be discouraged from obeying the law if he observes that others instead take advantage of it. Instead, a culture of being astute and taking advantage of others emerges. García-Villegas (2017, p. 93-93) writes (own translation):

The astute is a character that all Latin-Americans are acquainted with, not to say we carry it within. It is found from the Cañon del Río Grande to the Patagonia (...) In the southern-cone countries, "the astute lives of the silly, and the silly of his work" and in the Andean region "the world belongs to the astute" (...) In Venezuela, "the shrimp that falls asleep is washed away by the tide" (...) Pedro Nuñez de Cáceres, a Dominican lawyer living in Caracas in the late XIXth century, was surprised with the many expressions in Venezuela to describe someone who had been tricked by someone else's deceipt or cleverness.

In Fergusson, Molina, and Robinson (2017) we provide empirical results consistent with this mutual justification, but perhaps an anecdote is more revealing. In a televised debate for mayoral elections in Bogotá, candidate Antanas Mockus asked candidate Samuel Moreno the following question: "If you could buy 50 votes and thus avoid victory from a candidate who buys 50,000 votes, would you do it?" Samuel Moreno response was: "Yes, no doubt". Moreno won, not surprisingly! And he became the champion of clientelism with government contractors, in the so-called Cartel de la Contratación. He is currently in jail.

5. Breaking the social contract: undermining the role of elections and other oversight institutions.

Clientelistic vote buying also undermines the ideal role of elections and other oversight tools. Ideally, voters should vote and then control the winner, make sure promises are fulfilled, and complain and withdraw future support if they are not. But with clientelism voters give their vote, get their money or direct benefit, and the deal is over. Thus an essential oversight incentive in democracies is hurt. And this problem goes beyond voters. All other clientelistic exchanges benefit from opacity, since they are either illegal or sit in uncomfortable gray areas. Thus, those involved have every incentive to dismantle transparency.

6. Powerful groups, not citizens, control the state.

If citizens at large do not control the state, someone else will. With prevailing clienlelism, politicians or specific interest groups participating in the clientelistic relationship capture the state. This may include mafias capturing resources from the state, and who in turn may provide funds to buy votes and continue receiving benefits and diverting resources. It can also be public employees whose employment is a reward for political support, and not based on merit.

7. Controlling with a small budget.

Finally, even ignoring its consensual nature, clientelism is also detrimental to the sheer magnitude of state capacity because it is a very cheap form of social control. By relying on small transfers, social networks and other traditional forms of control, it does not even require a large state. Robinson (2007) explores this idea and proposes that the emphasis in clientelism, rather than populism, therefore differentiates Colombia from other countries in the region only on form, not so much on substance.

In short, the very prevalent clientelistic nature of political exchange is a key cause of the weak state, and vice versa. Fostering change is therefore very challenging, an issue I now address to conclude.

Notes: Incidence of clientelism (upper panel) or tax evasion (lower panel) as implied by the list experiment (diamond), direct question (square), and the difference between these two measures, capturing the extent of Social Desirability Bias (SDB, triangle). Lines mark 95% confidence bounds. Source: Fergusson, Molina, and Riaño (2018); Fergusson et al. (2019).

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

I have painted a very grim picture. Many people do not particularly dislike or disavow violence. They may either directly support it or indirectly perpetuate it through the support of a weak state, with violence as one of the side effects. I have emphasized "vicious circles" and, "curses", and "traps". A weak state and its mirror image of persistent violence are in place for powerful reasons. They are part of a deeply embedded political equilibrium, with many reinforcing feedback loops. They are so ingrained in society that, beyond material incentives, an accompanying set of norms emerge and, also, reinforce the status quo. Escaping such a system is not simple. Many things must fall into place simultaneously; efforts must intend to make progress on many dimensions at the same time.

Therefore, one should probably not expect miracles. But there are also reasons for hope. First, typically there is a virtuous version of the vicious circles and mechanisms that I have studied. Just as a low supply of public goods tends to depress the demand for them, a drive to increase public good provision can plant the seeds for a revived demand for them that keeps the state responsive. Also, while clientelism engenders a weak state, entrenching clientelism and so on, the rise of non-clientelistic politicians can strengthen the state, which further opens the way for less clientelistic forms of political exchange.

Second, the research I have reviewed produces a few lessons that may be useful for reformers and leaders. In several instances I have emphasized that remedying political disparities is even more fundamental than just correcting economic ones. Giving people a voice and true political power may therefore be a more effective path for change than just seeking to solve their material scarcities. Of course, in the midst of a very clientelistic environment, one has to worry about any such initiative being captured by clientelism. A telling example comes from the set of social reforms embedded in the Colombian 1991 Constitution. The Constitution granted citizens with basic rights to access education and health services, among others. Citizen's demands and legislative reform implementing the Constitutional changes have greatly increased public goods in health and education. Yepes, Ramirez, Sanchez, Ramirez, and Jaramillo (2010) (see also Robinson, 2015) highlight the dramatic increase in health expenditure and coverage in the 1990s.17 This appears to be a bold and real move towards a consensually strong state. At the same time, health services are also plagued with clientelistic relationships, as the "Hemophilia Cartel" scandal recently illustrated. Fake hemophilic patients were created out of thin air to capture resources, and one former governor and other politicians are involved in the investigations.18 A similar scheme involving fake or so-called "ghosts" students was introduced to capture resources transferred to schools (Fergusson, Harker, & Molina, 2018).

Third, tax reform can also be very important to change the equilibrium. Colombian elites have been notoriously difficult to tax (Alvaredo & Londoño, 2013). Consistent with the public goods trap and the mutual justification in defaulting, a common rationale of tax evaders and those opposing tax increases is that, unlike other states, the Colombian state offers no public goods. Without "skin in the game", and without benefitting from taxation, those with more economic resources have little motivation to contribute. Yet perhaps, to build a state, the proposition must be turned on its head: tax capacity must increase first so that politically powerful groups feel the burden of taxation and are enticed to make the state responsive, to promote the complementarity between control and power. Martínez (2016) finds that money from national transfers translates into less public goods than money from local taxes in Colombian municipalities. One of the mechanisms that may be behind the findings is that when citizens pay taxes, rather than receiving transfers, they are more willing to invest time to be informed about the way in which the money is spent. This can increase the quality of governance and the provision of public goods by enhancing accountability. This is easier said than done, of course. Recent efforts to impose reasonable income taxation and Pigouvian taxes on some goods has faced strong resistance.19 But it should be a fundamental part of the agenda to build a modern Colombia. Evidence from the work of Weigel (2017) in the Democratic Republic of Congo indicates that increased tax collection increases citizen political engagement.

Also, while I have emphasized the elites who intentionally want to prevent change, there surely are many that want change but are trapped in a collective action problem. Taxation is again a good example. The weakness of the state reflects a complicated tax code full of exceptions and special treatments that businesses and individuals have received (not surprisingly, in a clientelistic fashion). But perhaps many of these beneficiaries would in fact prefer a more rational tax code, without unjustified exemptions and targeted subsidies, that could raise more resources with fewer distortions. If this strengthens public finance and allows the government to provide better public goods for productivity, like a highly qualified labor force, good road and port infrastructure, technical assistance, etc., everyone would be better off. But of course no one wants to be the first to surrender the special benefits. In this case, good leadership as a coordination device can make a difference.

Of course, I left aside a number of topics that are also important to think about the best way forward. One particularly important yet unexplored issue in this essay is that, especially in contexts of persistent civil war as the one I discussed, one frequently observes the emergence of some sort of social order in conflict-prone areas (Arjona, 2014, 2016). That is, a set of formal and informal institutions shape the way society is organized, creating some "predictability", in particular in the interaction between civilians and armed actors. Most of my analysis focused instead on the more macro-level interaction between the state and insurgents, or the state and citizens. But a clearly relevant area of research is understanding how the stability of these wartime orders feedbacks into the persistence of civil war and the challenges to building consensually strong states. Undoubtedly the difficulties in altering these orders (and the way they blend with state institutions and rules) is likely another powerful obstacle to building something closer to the ideal type I have described.

Perhaps nothing illustrates better the mix of opportunities and difficulties for state building than the recent peace process with the Farc. Returning to the initial portrait of Colombia I painted in the introduction, the recent years suggest a different trend. Partly as a result of this major peace process, several violence indicators decreased. The ministry of defense reported (Ministerio de Defensa, 2017) that the number of military killed in combat has decreased steadily since 2011, from about 480 per year to 113 in 2016. Guerilla members too, from a peak of more than a thousand in 2008, to a bit under 600 in 2009, and then a roughly linear decrease all the way to 59 in 2016. Victims of landmines and other explosives have fallen from 859 in 2008 to 84 in 2016. The list could go on.

Despite these developments, a referendum to ratify the initial terms of the peace agreement with the FARC was rejected at the polls, animated by a powerful opposition. Juan Manuel Santos, the president who pushed this remarkable historical achievement, left office as perhaps the most unpopular president of recent times. This apparently paradoxical situation becomes probably less so after considering all the vested interests in maintaining some aspects of the status quo, which could be shattered by the commitments the government made in the peace process (which was finally modified after the plebiscite and ratified in Congress). Some of these commitments have at least the potential to contribute in the direction of building a more capable state: regional inequities in access to public services are supposed to be tackled, under-represented areas of the country are meant to have privileged political representation, social movements will be strengthened, land acquired illegally must be returned to the rightful owners.

In the process of implementing the accords, the nature of the challenges ahead have been clearly revealed. First, the state has been very slow in the implementation. A limited political capital and sheer incapacity (an incapacity to build state capacity trap!) are two likely reasons. Second, members in Congress delayed the implementation and blocked some of the proposed reforms by voicing concerns. There were several motivations. On the one hand, pure clientelism: "legislative extortion" to get bureaucratic quotas in exchange for supporting the government.20 On the other hand, fear about the effects of some of the proposals. For example, one of the points of debate is the role of "third persons", namely wealthy individuals taking part in the conflict by financing and supporting paramilitaries. The peace agreement stipulated that they too had to respond to a new transitional justice system. But prominent political leaders (including Santos' own former vice-president) opposed, arguing that there would be a witch-hunt against innocent victims of paramilitary extortion.21 The concerns may be legitimate, or may (more realistically, perhaps) also reflect a fear of losing a historically privileged treatment that elites enjoy in the status quo I described in this essay. Finally, security challenges abound. Delayed implementation is a perfect recipe for dissidences of reintegrated rebels going back to arms, on their own or recruited by the strengthened armed groups that have filled spaces left by the Farc and not covered by a sluggish state. Social and political leaders, as well as Farc members, have been assassinated at alarming rates. Colombia is in a true critical juncture that could turn things for the better, or change many things only to remain the same.