INTRODUCTION

In the context of the armed conflict in Colombia, active and retired military officers have been criminally prosecuted for being linked to armed confrontations between state forces and outlaw armed groups in which civilians were killed in. The treatment of these cases is a function of the military criminal justice system when it comes to acts carried out as part of military service, and in other cases, they are judged within the civilian justice system. The latter unfolds when they fail to demonstrate that the deaths of civilians in military operations are due to clashes with outlaw armed forces and are judged within the state justice system as human rights violations.

Personal and non-institutional justifications characterize the extrajudicial executions in which members of the security forces are involved. Those operations sought to achieve the results demanded by superiors and resulted in the so-called "false positives" (Reveles, 2012). "False positives" were produced by military units under pressure to apprehend guerrilla fighters, so when they failed to obtain results, they decided to carry out operations to cook up weapons and victims, who were civilians identified as members of armed groups who had been deployed in military assaults. Those outstanding results meant rewards for those soldiers involved. Later, some crimes were corroborated through testimonies of people who lived the conflict zones, the rest were confirmed by soldiers and their commanders to obtain a reduction in their prison sentence, then the intensification of the conflict and the delegitimization of state actions provoked the armed forces to be considered as an actor in the conflict and, therefore, to be required in the Transitional Justice System (TJ).

At present, there are still debates about the effects at the state and individual level of the TJ, since there are opposing statements about their consequences and exact mechanisms. A review of recent TJ studies reveals that empirical evidence is diverse. In this regard, Thoms, Ron and Paris (2010) argue that a more systematic and comparative analysis of the TJ record is needed to move from discussions based on faith to arguments based on facts, understanding that in many cases the individual subjectivity can generate biased understandings of the global perspective.

In most cases, the evaluation of the TJ effects is based on aggregate groups which do not allow for an objective assessment of individual actors in the conflict. In consequence, unless each case is treated separately, it is not possible to weigh the impacts accurately. According to David (2017), justice is understood as a sociopolitical category rather than a legal category, a deployment of the concept that leads to different results. For this reason, this document deals with the detained soldiers as individuals and not as part of an institution or an aggregate.

Through the information collected via a survey, this document analyzes the perceptions that the military officers in Colombia have of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP in its Spanish acronym) in the wake of the armed conflict. In total, 333 inquiries were made of active and inactive personnel of the National Army who at the time of the study were being deprived of their freedom in prisons and penitentiaries for members of the Public Force of High and Medium Security (CPAMS). The survey contained socio-economic, family, and legal questions, and also an open response module that sought to account for the perception of the military about different aspects of the JEP: time of incarceration, trust in justice, experience (if any), state capacity to absorb failures of the JEP, post-conflict and reintegration. This information was processed through a mixed method. It was found that although the advantages of participating in the JEP are evident, at least in terms of sentencing time, there is not a generalized feeling of optimism since there are no sufficient legal guarantees and they feel that they are at a disadvantage compared to FARC combatants in terms of judicial processing.

This document is divided into six sections. After this introduction, section two exposes an exploratory analysis of the historical experiences of TJ elsewhere in the world and an account of the Colombian case. Section three outlines the current judging system for the military forces. The fourth section describes the methodology used for the analysis. The fifth section provides the corresponding interpretation of the data and the results. Finally, the sixth section summarizes and concludes.

THE TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE EXPERIENCE

According to the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ, in its acronym in English), "transitional justice is the set of judicial and political measures that various countries have used as reparations for the massive violations of human rights" (ICTJ, n.d, p.1). To this end, different criminal actions, truth commissions, victims' compensation and institutional variations will be included, depending on the specific situation of the country or nation to which it applies. This justice will then seek a transition towards democracy or a solution to internal conflicts, although there are cases where these conditions are not necessary, as in the case of Mexico. There, Cantú (2014) reveals a de facto type of TJ within the authoritarian governments that in their recent fight against drugs have violated human rights and have co-opted extreme amounts of power, for which a specific jurisdiction was created to consolidate peace. However, not only should it constitute a set of measures aimed at punishing the perpetrators and reparations for the victims, but it should also focus on a reconciliation avoiding social division (Rojas-Páez & Guzmán-Rincón, 2016). As Teitel (2000) states, the application is not satisfactory for all those involved since the traditional concept of justice derived from the consensus must be discarded to make way to achieve the social goal of moving towards a more liberal democratic system.

Although each TJ process has unique features, the United Nations (UN) through the Human Rights Council generates a broad explanation where it argues that TJ covers the full range of judicial and non-judicial measures, such as individual prosecution, reparation, truth-seeking, institutional reform, background checks on public officials, or an appropriate combination of these measures, in order to guarantee justice, provide remedies to victims, promote the recovery of normalcy and reconciliation, establish independent entities that supervise security systems, restore confidence in state institutions and promote the rule of law in accordance with the law from the human rights (ONU, 2012).

In line with the above, Valderrama and Ortiz (2017) conclude that, although there are supranational organizations such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights that provide non-amnesty for crimes against humanity, the TJ has the flexibility to achieve the objectives that will foster peace. Wolfgang (2012) shows an example of this in the international context where TJ claims the right to truth and memory, however painful it may be, in cases like the Eichmann trial in Israel, the South African Commission of the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) after Apartheid and the National Truth Commission of Brazil (CNT) after the military regime. State agents are often actively involved, sometimes directly, sometimes through omission and other times under alliances with certain outlaw groups, in the different events and conflicts that trigger the subsequent need for a TJ. Armed forces become a crucial element in these processes since, in addition to its military capacity, it is generally one of the institutions with the highest presence at the region level.

Colombian Context

Jaramillo (2014), underlining the fact that Colombia has suffered more than five decades of armed conflict, where different actors have maintained constant struggles against the social order, the state and other outlaw groups, stresses that, throughout this period, the country has tried to uncover the facts that have surrounded all these events and has had twelve national study commissions and extrajudicial investigations regarding the violence. This effort for the clarification of the truth and the construction of historical memory has been fundamental to the peace process and has created the foundation for the truth commissions that will later meet the aforementioned characteristics of an effective commission (Hayner, 2008).

Antecedents

Diverse actors have contributed to the formation and the dynamics of this context throughout the country, each of them with different idiosyncratic genesis. Many of those actors have transformed to become smaller operational cells over time, known as the Bacrim (Quintero, 2017). In a brief outline of some TJ processes experienced in Colombian history, the one known as "Forgiveness and Forget-fulness" is highlighted. This process was born to demobilize the leftist insurgent group April 19th Movement (M-19), that was born after dissatisfaction with the fraud in the presidential elections of April 19, 1970, where General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, despite having broad popular support and favorable polling ended up losing to the conservative candidate Misael Pastrana (Ayala, 2006). This group began as an urban insurgent organization in 1971, but by 1974, it had consolidated into a guerrilla group and expanded into rural territories (Narváez, 2012).

Aguilera (2009) acknowledges that the group took advantage of the widespread discontent to promote its rise in the nation through populist actions and dissemination of information through the infiltration of radio and television channels. Although initially, they began with symbolic acts such as the robbery of the sword of the liberator Simón Bolívar in 1974, later the group utilized kidnapping for extortion and pressure to finance their operations and achieve political objectives. Finally, the seizure of the Palace of Justice in November 1985 is the point of decline of the organization (Gómez Gallego, Herrera Vergara & Pinilla Pinilla, 2010). Albeit, on principle, the ordinary justice system took the cases of the commanders and participants of the seizure, it was by Law 77 of 1989 that the Government granted them a pardon and the outstanding debts of the M-19 were waived by Colombian law.

The armed forces clearly demonstrated their dissatisfaction with the eventual truce between the members of the M-19 and the EPL as well as other efforts extended to the guerrillas of the FARC and the Quintin Lame. For example, an interview for the commission of truth with General (r) Rafael Samudio referred to the armed forces as an organization forgotten by the government of President Betancur which had a complacent attitude towards the insurgency (Gómez et al., 2010).

The federal military forces were disappointed because they thought that the peace accord was signed only to satisfy the whims of the guerrilla group and the generals were not heard, they were never heard, and instead a truce with the rebels was agreed upon. Nor will it be more than an instrument of pressure manufactured by international subversion (Landazábal, 1985, p. 265).

The amnesty would end up weakening the authority of the armed forces as it would undermine efforts to imprison militants of these groups by removing them from prisons. There was also public derision for those active military members accused of belonging to the movement Death to Kidnappers -MAS- which was created by drug traffickers to avenge the abduction of Martha Nieves Ochoa, the sister of members of the Medellín cartel leadership, although this charge was eventually passed down to the Military Criminal Justice system (Ramírez & Restrepo, 1988).

The excessive use of force and the efforts of the authorities to regain control when the Palace of Justice was seized by M-19 (called the resumption) put the military in the eye of the hurricane, as the public became aware of actions committed by agents that involved serious human rights violations (Tribunal Especial de Instrucción , 1986). In addition to the tasteless pardon granted to M-19, in 2005 the case against the military forces was reopened through Resolution 3954 of 25 November 2005, which generated indictments against several members of the FFMM, increasing military mistrust of the judicial process.

Another broad TJ process is known as "Justice and Peace", in which the paramilitary groups, which were born from a series of events such as guerrilla growth, increase in drug trafficking, and uncertain peace under the government of Betancur (Cubides, 2007) became central. However, the Historical Memory Group-GMH- (2013) indicates that the milestone of the birth of paramilitaries is the MAS movement that, as previously mentioned, was a group created by drug traffickers to avenge the abduction of Martha Ochoa.

Soon these paramilitary groups began to offer landowners "security service" protection in exchange for payments, which caused their numbers and the zones of influence in which they operated to increase alarmingly (Romero, 2003). In addition to this, Betancur's approach to peace increased the forgetfulness of the state towards the armed forces, which led some of its men to swell the ranks of their self-defense groups (CNMH, 2013). In the paramilitaries' first ten years, the number of men increased by almost 1000% (Sánchez, Díaz, & Formisano, 2003). This condition, along with a newly established democratic regime of regional elections in 1982, resulted in a dispute over the territories becoming entrenched in violence which, accompanied by state abandonment, facilitated the coopting of regional governments and the deepening of conflicts, according to the thesis of Goldstone and Ulfelder (2004).

Through Decree 356 of 1994, the government allowed the creation of armed surveillance cooperatives for those rural areas where the state could not be present; such as groups were in legal limbo for prolonged periods. Among the criminal actions of the paramilitaries were all types of human rights crimes and violations of international humanitarian law, as well as crimes impacting public health such as drug trafficking. These armed surveillance cooperatives climbed to power, even infiltrating the local and national government (Pulido & Martínez, 2018).

In 2002, dialogues began with the national government that sought the demobilization of these groups. In 2003 the Pact of Ralito, between the government and the Self-Defense Groups, and finally in 2005 with Law 975 of 2005, the milestone of establishing a TJ, the "Law of Justice and Peace", was achieved. This law sought to emphasize the importance of punishment, although minimal, since such punitive measures ranged from 5 to 8 years, and it also clarified the truth and reparations that would be due to the victims.

As the process for obtaining the truth progressed, the relationship between state agents and paramilitaries was increasingly evident, being the armed forces one of the critical pieces in this relationship (Uprimny & Saffon, 2008).

Special Jurisdiction for Peace

Quintero (2017) tried to explain the genesis of the FARC throughout a hostile halfcentury that saw a high concentration of power and land among the wealthy few which subsequently gave birth to guerrillas, whose principal objective was a social struggle for more equity in access to power and land. The FARC was born under this name in 1966; they boast the achievement of being the longest-lived guerrilla organization in the world (Pécaut, 2008). The FARC is the insurgent armed group that has left more victims in Colombia than any other group. According to the GMH (2013), there are 20,000 documented deaths, 5.7 million people displaced in rural areas, more than 25,000 disappeared and almost 30,000 kidnapped. This group committed numerous human rights violations, as well as violations of international humanitarian law and coordinating with drug cartels. Villalobos (2008) criticizes the actions of the group that, disguised as a struggle for justice, developed an extensive network of drug trafficking linked to some of the most powerful cartels in the world and generated substantial revenues.

The attempt of the Colombian state to achieve peace with this subversive group is not new. Since the 1980s, different governments have tried to generate approaches without success. It was not until the government of President Andrés Pastrana (1998-2002) that the first peace dialogues were initiated, with permanent international accompaniment, and a broad agenda for discussion and public hearings. Unfortunately, they were not successful (Leguízamo, 2002).

Finally, a new hope for peace came with the government of Juan Manuel Santos in 2012, when a negotiation table was announced in Havana, Cuba and work was carried out on a "general agreement for the termination of the conflict and the construction of a stable and lasting peace", which was the protocol for the talks (González, 2015). After four years of negotiations and several suspensions for breaches of the ceasefire between participants, the signing of the peace accords was finally announced.

A framework of TJ called "Special Jurisdiction for Peace" (JEP, in its Spanish acronym) was established by Decree 1592 of 2017, which along with some complementary laws such as Law 1448 of 2011 or the "Law of Victims", sought to generate an environment conducive to the achievement of peace. To this, the JEP adopted the four premises that the UN promulgates as fundamental for peace's success: a) the obligation of the state to investigate, prosecute and convict perpetrators of different crimes, especially against human rights, b) truth, c) reparations and d) the prevention of repetition of criminal acts (UN, 2014).

Concerning the public force, this peace process had a particular focus compared to those before it: the active participation of the armed forces at the negotiating table, as well as the recognition of the state as a perpetrating actor within the conflict, for which the JEP could evaluate crimes committed by agents of the state that are directly or indirectly related to the conflict. The JEP could "adopt decisions that grant full legal security to those who participated directly or indirectly in the internal armed conflict through the commission of the mentioned conducts"(Law 1592 of 2017).

Taking into account that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights -IACHR ordered Colombia in 2015 not to include crimes against human rights committed by members of the security forces in the Military Criminal Justice System (Agencia EFE, 2015), the new jurisdiction became an attractive legal alternative for all crimes committed in acts of service and whose relationship with the conflict is evident. Although Benitez, Quintero, Márquez, & Ortiz (2015) identified the recognition of the rights granted to members of the military forces in TJ processes, from a review of countries that have gone from dictatorship to democracy and from war to peace, in order to expose which could be the rights and guarantees granted to the members of these forces during the transitional justice process in Colombia, how they will approach this transition is still underexplored.

Thus, the framework of action for the JEP is the broadest within the TJ processes Colombia has experienced since all kinds of actors could potentially be included within it. Thus, included are not only combatants but also politicians and even civilians who have committed crimes motivated by the armed conflict. In addition to this, the statute of the JEP establishes the creation of a court that will analyze all the cases that enter it as new, without considering previous convictions for the same events.

The participation of the armed forces at the negotiating table allowed them to receive benefits similar to the insurgent groups. Some authors such as Gómez (2016) highlight the new TJ system according to modern trends of law and justice, and freedom from ideological biases and individualizations.

Although the current transitional justice process has made an effort to include the military forces as an actor in the armed conflict. Within the military forces, there are high levels of dissatisfaction with unequal treatment with groups outside the conflict that are also part of the process. Also, it is not common to obtain individual statements from the institution or from personnel hosted by TJ

International Context

The results in society derived from the TJ can be varied. Bakiner (2010) analyzes the progress and limitations of TJ's efforts in Chile through the examination of a key political actor: the armed forces. The former attitude of the military of denial and non-cooperation concerning the human rights violations of the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990) was slowly replaced by dialogue with civilians, institutional recognition of violations and limited cooperation with the courts. Although the strategic interactions with other political actors and the generational /personal changes stand out as variables that explain the behavioral and ideological transformation of the army, the article highlights a third crucial factor: the pluralization of truth and justice mechanisms, both national and international, that legally opened social and political fields of challenge against impunity and oblivion. Finally, and before an arduous process, a paradigmatic change was achieved in the armed forces that included repentance and non-repetition.

None of the main political actors in Chile, including the military, could exert total control over these multiple channels of truth and justice. The result was the adoption of new legitimizing strategies and discourses in accord with human rights. The army reoriented its position on human rights in the context of Pinochet's arrest in London in 1998, a changing political environment and the legal battle for amnesties for the abuses of the dictators.

Another case where the tate was responsible for a very high percentage of crimes against human rights was Brazil after the coup d'état of 1964, where the significant repression made the military and police forces directly responsible for abuses. A subsequent adjudication was omitted due to the Amnesty Law enacted in 1979. This omission allowed gaps in an ultimate reconciliation to be perpetuated in the transitional regimes and it is for this reason that since the beginning of the 1980s, the Brazilian state has made efforts to compensate the victims of the dictatorship. Even though many continue to cry out for the truth, the Truth Commission, created in 2012, focuses on clarifying the facts of this era without enacting punitive consequences (Leão, 2013).

Another emblematic case that includes systematic violations of human rights by state agents and insurgents is that of Sierra Leone, where Ginifer (2003) carries out an analysis of the reintegration of ex-combatants, emphasizing that the principal role of the military forces was a reactive one before the rebellion of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). However, there was a systematic violation of human rights by the different actors, formally ending in 2002. Their first obstacle when it came to returning to civilian life was a prevailing fear within the society of the acts of the past, taking into account the innumerable atrocities. Additionally, the limited capacity of the state to educate and create jobs was conducive of a high rate of recidivism, which the support of entities external to the government was essential in combating. This outside support allowed an adequate transition towards normalcy, accompanied by a process within communities to facilitate acceptance of ex-combatants. This is particularly difficult since there is resistance to giving opportunities to these people, who can be considered "rewards" for their actions in addition to many ex-combatants fearing for their lives.

Something similar happened with the ex-combatants of the civil war in Mozambique, where Wiegink (2013) describes the particular case of those belonging to the RENAMO and finds that reincorporation into civilian life was especially difficult for both the ruling party and the rebel forces. In addition to being a process with shallow involvement, it was further complicated by deep identity-based hatreds within the society and fear of "witchcraft" or traditions that were perceived to threaten life. In this type of context, ex-soldiers show widespread disdain for international institutions and organizations such as the UN.

But not all of TJ's attempts have been satisfactory despite the existence of supranational bodies such as the IACHR (1997) that in theory, regulate amnesty in cases of crimes against humanity or serious human rights violations. For example, Umukoro (2018) refers to the "attempt" of TJ in Nigeria as a sample of a co-opted state because after its failed commissions, especially the 1999 Commission of Investigation of violations of Human Rights, failed to consolidate a regime of transition after the military governments that had committed sevear human rights violations, mainly against the communities of the Niger Delta. The armed forces had a fundamental role in these processes as they were in charge of occupying territories for the extraction of crude oil. In this instance, a weak state apparatus combined with corrupt governors showed little initiative in bringing the accused to hearings to obtain the truth.

The Iraqi case is not far behind and has had broad international visibility. Iraqi TJ was widely criticized because it was a "justice of the victors" thanks to the latent influence of the United States where entities that assumed the judgments like the Iraqi Special Court (IST), later High Iraqi Court (IHCC) and the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) ended up emptying the state apparatus in its eagerness to eliminate any residual Baathism. About 500,000 soldiers were discharged from the force, many of whom had to be reinstated to their work, not only because it was merited, but also because it was not possible to prove any culpability under the official legal structure.

Algeria is a case of forgiveness and forgetfulness, where amnesty was granted in a first attempt to stop the violence. Subsequently, immunity was granted, and finally, in 2005, President Bouteflika called for a referendum to also grant clemency to Islamic fighters and state agents and military forces. That was done in combination with the disbursement of monetary compensation to victims. However, the insurgency continues to grow, and human rights organizations have been increasingly demonstrative in their claims to the government for the thousands of disappeared persons (Wiebelhaus-Brahm, 2016).

The TJ and its correct application constitute a fundamental pillar for the cessation of hostilities. Its absence can lead to spirals of violence and corruption on a large scale, such as the Afghan case where Saeed and Parmentier (2017) show that after the attack on the twin towers, post-Taliban Afghanistan initiated what was called the "Plan of Action for Peace and Reconciliation" in 2006. This element was initially weak and later omitted as a strategy to maintain order in the short term since the current political system would falter if its application became effective. Finally, continued impunity and inequality in land tenure generated new outbreaks of discord between different groups in the society and, eventually, new conflicts.

These arguments are consistent with the findings of Castel (2009) who, through the experience of Rwanda and Burundi, shows that traditional justice is, in general, biased or at the service of the most important political force of countries with weak institutions. This prevalence is even more profound when nations recover from complex events such as the genocide in these two African nations that used traditional courts like the Gacacas in Rwanda and the Bushingantahe in Burundi, resulting in high rates and lengths of sentences in the absence of comprehensive reparations to society and favoring the Tutsis in both cases.

Although in the literature the focal analysis of agents of the state is very superficial or non-existent, Sokoli (2016), through an investigation with focus groups for the case of the independence of Croatia, studied the judicial narrative versus the narrative of war in order to understand the role of TJ and its sentences. Three groups were chosen: pensioners, middle and high school teachers, and war veterans. They all agreed with very clear positions about the actions of Serbia against Croatia, generally extolling their heroic actions and justifying them as a legitimate defense against the Serbian invasion. The administration of the TJ, in this case, was imperative since it was awarded to the Croatian authorities through the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) whose trials proceeded in line with the popular beliefs mentioned above. Additionally, factors such as having been a policeman or military officer were excluding factors so that the success of this system was very satisfactory and tended to achieve the long-term objectives of TJ.

As previously observed, international literature affirms that the treatment that has been given to agents of the state is still very superficial; the process lacks a systematic investigation of behavioral patterns. An obvious reason for this is that these state actors are perhaps some of the most marginalized in the society after this process because they have been shown to have broken oaths and defrauded the trust that their nations had put in them.

CURRENT JUDGEMENT OF THE MILITARY FORCES

At present, military forces can be tried in three-justice schemes: i) Military Criminal Justice, ii) Civilian Justice, iii) Special Justice for Peace. The application of each depends on the conduct in question. Conduct deemed to be an act in violation of military regulations is judged within the military justice system. The ordinary courts will judge conducts that represent violations of human rights or civil law and which cannot be justified within the actions of an institution. The Special Justice for Peace will include all those crimes that would otherwise be judged in the ordinary courts but have a direct or indirect relationship with the armed conflict. The legal framework for the application of each justice framework is as follows:

Military Criminal Justice: Regulated by law 1410 of 2010, this system judges all those crimes committed during military service that derive from official orders given by superiors with the exceptions of "torture, genocide, enforced disappearance, against humanity or those that Attempt against IHL ... or conduct that is openly contrary to the constitutional function"(Military Penal Code, 2010)

Civilian Justice: Judges individuals who have committed some of the behaviors excluded from the previous category crimes against humanity and crimes against international humanitarian law. For this jurisdiction, there are basically two laws under which any individual can be tried depending on the date of occurrence of the conduct in question. The first is Law 600 of 2000, "Inquisitorial Criminal System", and the second is Law 906 of 2004 or "Accusatory Criminal System". The main difference between these laws lies in the form of judgment. As applies to Law 600, the judge accuses and makes the final judgment. Under Law 906, this function is decentralized.

Special Justice for Peace (JEP): Through Law 1820 of December 30, 2017, the Colombian State defines the benefits and conditions for insurgents and agents of the State (including members of the security forces). In the case of the public force, all those accused or convicted of actions that are directly or indirectly related to the armed conflict are subject to this justice system. The benefits offered are:

Transitory and conditioned freedom

Suspension of arrest warrants

Responsibility of command

Legal security

Waiver of criminal prosecution

Prevalence of the JEP over any other criminal, disciplinary, fiscal or administrative action.

Additionally, those members who have been deprived of their liberty and who subsequently receive a sentence with the JEP will obtain an effective discount in their late penalty equivalent to the real time of imprisonment to which they have already been subjected. In other words, a person who receives a condemnation having already been incarcerated will receive recognition for this time and will only have to serve the prescribed sentence time dating from their first day of imprisonment prior to sentencing. An significant advance in this process is that there will be no preventive assurance measure1.

DATA USED

In this research, a questionnaire was used as a collection instrument, consisting of 53 questions, of which 70% are quantitative, and 30% are qualitative. The survey applied to the staff had an initial pilot test of fifteen individuals where additions and corrections of some questions were made, but the structure of the questionnaire was not affected. The final survey was comprised of four modules divided as follows:

Module I General Information: Seeks to identify the individual through his age group, rank, education and health status.

Module II About the process: Investigates the causes of imprisonment, types of crimes, convictions, and defense expenses, among others.

Module III Economic and family: Examines the individual's economic conditions after the process, as well as the dynamics in the family nucleus.

Module IV Open questions: Seeks to understand how the Special Jurisdiction for Peace views the defendant.

These modules are intended to investigate how the individual has generated an understanding of the JEP that has allowed him to make value judgments about his own process and the general process. The closed questions facilitate the creation of scales that quantitatively indicate these perceptions, while the open questions yield insight into the social constructs that, in part, determine how respondents perceive the JEP.

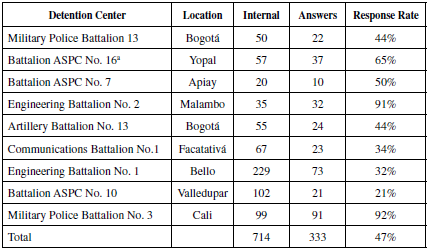

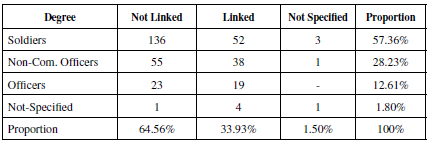

The data used correspond to active and inactive personnel of the National Army of Colombia, deprived of freedom during November 2017. A survey was conducted in each of the CPAMS, where each of the inmates could decide to participate or not in the exercise. Ultimately, 333 inmates of 714 participated at the beginning of the study2. Non-participation was due to several factors. The first was that a significant number of them, at the time of the visit, was in the midst of legal proceedings. Second, in some centers, there was paid work and many of the prisoners were working at the time of the visit (as in the case of the Engineers Battalion No. 4). Another reason was that some inmates were being prosecuted for actions unrelated to the conflict and therefore, did not make up a relevant part of the sample. Finally, individuals refused to participate in the exercise due to fear or merely lacking interest in the subject. However, the latter corresponds to a small minority proportion of the population as the surveys were conducted during training first thing in the morning and were usually ordered by the officer in charge. Therefore, it is not likely that the collected sample contains a major bias. Table 1 and Table 2 show the former military participation in the survey by degree and by connection to the institution.

The participation rate adjusted to the data at the beginning of the survey cycle is as follows: For the interpretation of results two modules were generated, the questions of the quantitative type are analyzed by the SPSS software. For the qualitative module, the plausible theory of Strauss and Corbin (2012) is used. In this study, the data were systematically collected and coded through AtlasTI qualitative analysis software.

Table 1 Participation of personnel according to detention center

a Combat and services report

Source: author's format based on the survey results

Table 2 Responses by degree and by connection to the institution

Source: author’s format based on the survey results

It should be noted that there are only men in detention. Among the participants of the survey, the most significant volume of interviewees is concentrated in the soldier rank with 191 responses, corresponding to 57.35%, followed by NCOs occupying 28.22% and, finally, officers representing 12.61%, in addition to the remaining 1.8% that is not specified. Of the total, only 34% remain active within the armed forces, while the rest were discharged or are in retirement.

METHODOLOGICAL DESIGN

The research utilizes a mixed methods approach since it integrates quantitative and qualitative elements that allow a comprehensive analysis of the perceptions of the military involved in criminalized acts and that are currently undergoing the process of the JEP. Thereby, the unit of analysis corresponds to individuals held in military prisons who meet those characteristics.

According to Hernández, Fernández and Baptista (2010), mixed methods represent a set of systematic, empirical and critical research processes that involve the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, as well as their integration and joint discussion, to make inferences from all the information collected (Hernández et al., 2010, pp. 546). That is why the process heretofore undertaken is an adequate way to understand the phenomenon under study.

On the one hand, the qualitative element of the mixed approach used for this work is justified insofar as it allows the authors to understand and analyze the perceptions of the participants, as well as the textual descriptions of their feelings in relation to how they are being or will be judged by the JEP. This qualitative element of the methodology used is also justified because it allows a registering of the data provided by the interviewees in their own language since it is assumed that the real expressions of the military are transcendental in the process of converting them into results of the investigative work Likewise, It allows a study of the group of soldiers in the process of trying to understand the context and the current circumstances in which they find themselves.

On the other hand, the quantitative element is justified because, due to the collection mechanisms, it was possible to obtain numerical data expressed on the basis of their quantifiable properties. This being the case, this quantitative element of the mixed approach makes it possible to test hypotheses that complement or allow a better understanding of the perceptions of the members of the army who agreed to be interviewed, and allow for synthetic descriptions of the numerical data obtained.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

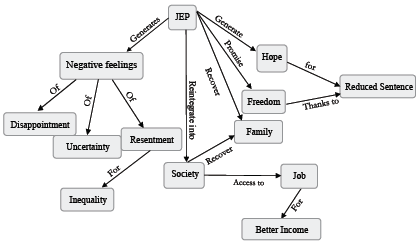

Figure 3 presents the semantic network in which it is observed that the JEP generates negative feelings in the respondents such as disappointment due to institutional abandonment, uncertainty in their processes and resentment at feeling inequality in the way JEP deals with outlaw groups. However, the implementation of the JEP also generates positive expectations related to the recovery of the family, the feeling of hope and freedom when their sentence is reduced and the possibility of reintegrating into society, which would allow them to improve their income.

By deconstructing the analysis of the network in Figure 3 by ranks, it can be confirmed that the soldiers perceive that JEP allows them to reduce time in jail and obtain their freedom more promptly; at an aggregate level, they consider it part of the process that will allow the country to move towards the end of the conflict. NCOs feel that JEP applies asymmetric treatment to themselves when compared to outlaw groups, as expressed by the following opinion "it is a situation that serves the military and is a benefit obtained by the guerrilla"(Suboficial 307). As far as the officers are concerned, their perceptions of the JEP are framed by the objective pursued by the peace process, as evidenced by the expressions of Officer 159: "[this is a] transcendental moment and opportunity for those who have made mistakes in the war". Officer 911 said, this "is something excellent, since it serves to end this silly war where we Colombians have been killed for 52 years".

The words of one of them confirm that statement when saying that he would welcome the JEP because he believes "that after God, the only hope of seeing freedom is the JEP, although there are not many guarantees, there is a light of relief (Official 913). Only 13% of the officers would not accept the JEP because the process seems unfair and unequal concerning the treatment of the insurgent groups. In this sense, regarding the process, one testimony stated: "it is a hoax. It is designed to clean up the guerrillas and assign responsibilities to members of the military force"(Official 168).

Likewise, as regards non-commissioned officers, 91.5% (86) declared that they would benefit from the JEP for reasons similar to those expressed by the officers, in fact, Petty Officer 726 stated that, "although one is not guilty, there are benefits and more importantly, decreases in the sentence which we did not obtain with the ordinary justice". This declaration provides a good example of the feeling of distrust for the institutions of traditional justice.

Finally, in the case of the soldiers surveyed, 95% would take advantage of the JEP for reasons such as guarantees in the process, being able to prove their innocence and reach their freedom more quickly. It is observed that, regardless of military rank, more than 87% of the respondents would benefit from the JEP for similar reasons.

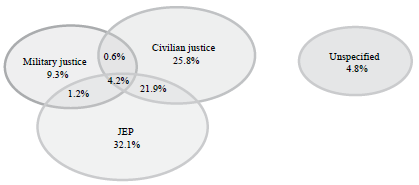

These high percentages (87% for officers, 91.5% for non-commissioned officers and 95% for soldiers) of military personnel who opted in to participate in the JEP process are the product of near-unanimous desire among inmates to benefit from its guarantees and sentence reductions. In fact, about 87.1% have already taken refuge or are in the process of receiving it, while the rest would not be given the opportunity either because the crime committed does not qualify, or because they prefer to continue under civilian justice as a personal decision based on their negative feelings towards the JEP.

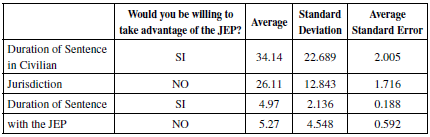

From an analysis of how the military personnel interviewed perceive the possibility of taking advantage of the JEP, it is evident that there is great hope for a reduction in sentencing for those who opt for transitional justice. This expectation is not unfounded, because when doing the statistical analysis, it is to be noted that the group of soldiers who wish to benefit from the JEP has a mean sentence time of 34.1 years. The group that does not want to use the JEP process has an average of 26.1 years if they remain in the Civilian Justice system. On the other hand, if one compares the average time of the expected sentence if they join the JEP for the two groups, the average is close to 5 years (Table 3).

Table 3 Statistics of the military that are willing to take advantage of the JEP and those who do not

Source: author's format based on the survey results

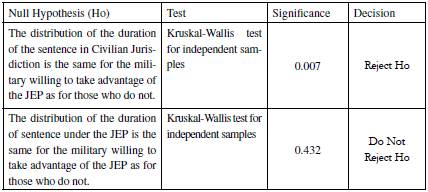

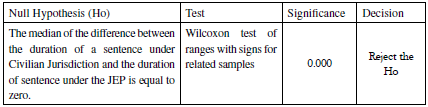

When comparing the distributions of sentencing times with the Kruskal-Wallis test, the null hypothesis is also rejected. This means that the military's perspective of taking advantage of JEP to reduce its sentence time is statistically validated (Table 4).

Additionally, the results of the Wilcoxon test corroborate the median difference between the duration of the sentence under Civilian Jurisdiction and the duration of the sentence under the JEP is not zero (0) (Table 5), which means that the sentence received for taking part in this process would be less than the sentence imposed under Civilian Jurisdiction.

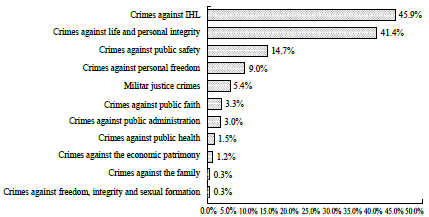

If the analysis is made considering the crimes in particular, the expectation of a shorter conviction is maintained. For example, for those who have committed crimes against International Humanitarian Law experienced an average reduction from 34.7 years to 4.9 years, a similar reduction occurs with crimes against life, which go from 29.2 years to 5.5 years. Likewise, crimes against life and freedom personnel would3 go from serving 21.7 years, on average, to 4.5 years. Other types of crimes, such as those that threaten public safety, would go from 11.9 to 6.3 years. It is important to bear in mind that about 62% of respondents are convicted, so for those who did not have a firm conviction at the time of the survey, they inquired about the possible sentence time. There are also some differences in penalties between legally similar individuals since 28.3% assumed an early sentence and those who have not done so have an average of 3.63 years as court-martialed. It is observed that 81% of the crimes committed by the individuals under study were during the period between 2002 and 2010.

Continuing with the deconstruction of the issues presented in Figure 3, for 86% of the respondents, being in the current situation elicits an emotional reaction due to family problems such as separation, the growth of children without the presence of the father and the increase in psychological burdens on family members.

82% of the respondents consider the events for which they began their process were typical of the internal armed conflict and clarify that they were in compliance with their duty and developing some operation. Besides, 52% accused the NGOs of intervening during their trials through different measures, mainly as representatives of victims, arguing that false witnesses are often introduced in order to obtain a significant compensation from the state, even when the victims were combatants from outlaw groups. These irregularities lead them, in some cases, to feel disappointment and resentment toward the military forces and, in other cases, the desire for freedom and hope. However, there is a degree of uncertainty, since they cannot be certain of the outcome of their process.

When analyzing by rank the perception of the military about the preparation of the state to guarantee them an appropriate reinsertion into society after the process, it is found that 92% of the officers, 74% of the soldiers and 68% of the non-commissioned officers consider the state to be unprepared. In some cases, this is because they feel that "the benefits for the members of the FFMM are very few compared with those of the FARC" (Soldier 709), and in other cases because "it is a slow process and we must work hard on the conscience of the people to accept us into society again"(Official 720).

In the case of perspectives on their future with conditional or definitive freedom, regardless of the military rank, in general, the desire is to recover their family life and seek employment alternatives to military service, in many cases of an independent nature. Another outcome they have expressed a desire for is an opportunity for studies that would lead to other employment, allowing them to integrate into society and receive an income to satisfy their basic needs. Nevertheless, it is found that 10 soldiers, 3 noncommissioned officers and 5 officers wish to resume their activities in the army, either for the love of the country or because they do not feel that they have opportunities outside the military. This is corroborated by the words of soldier 767 who said, "at this moment I do not know what I would do since I do not know anything other than military life. I am not really trained in any other area because I devoted my whole life to the army".

CONCLUSIONS

The of the interviews' assessment demonstrates that the benefits and the drawbacks of the JEP vary according to the military rank of the soldier being interviewed. For officers and soldiers, the JEP tends to be interpreted as a mechanism for ending the conflict and moving to a new historical era in Colombia. However, for non-commissioned officers, there is a generalized feeling of asymmetry in the treatment of soldiers and outlaw groups involved in the conflict, as well as the feeling of betrayal by the state and in particular by the FFMM.

Although a majority of soldiers within each of the ranks (officer, non-commissioned officer and soldier) are willing to join the JEP, the feelings and qualifiers towards it vary between ranks for several reasons. The first of these is that as the rank within the institution increases, the percentage of participants in irregular operations that are syndicated or convicted is less, which may give the impression that ordinary justice for these cases is more inflexible among the lower ranks. Therefore, there is more acceptance in this group. On the other hand, expenses for legal representation are lower in the lower ranks so the failure of legal battles of this scope can occur quickly in the face of financial insolvency, for which the JEP constitutes a viable and hopeful alternative.

As for the future that the military await, they generally hope that the JEP will reduce their time of incarceration and thus allow them to reintegrate into society, rebuild their family and complete their life goals. There is evidence of the need for a disruptive strategy by the state considering the difficulty of relocating to find work, as this is a point of recurring concern among the respondents.

These observations allow an understanding of the impact of the application of the JEP from the perspective of the military involved in the process. Based on this understanding, the judicial operators in charge of these processes have this tool to assess and understand the context in which these actors are immersed.

In short, the JEP is welcomed by the active and inactive members of the National Army, despite the obvious outlier of what they call unequal treatment between themselves and the FARC guerrillas, as well as a deep concern about what will come after: damages to the society, their role in work and family life, and the general uncertainty which poses challenges for future governments that must guarantee the socialization process together with an educational component for a healthy society.