INTRODUCTION

The peace negotiations were resolved between representatives of the national government and the delegates of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia - People's Army (FARC-EP, in its Spanish acronym) command. For both sides, the centrality of the accords was a pledge of commitment between the parties and the coherence of what has been agreed. In the other hand, it was proclaimed that the implementation of the accords would require the support of all levels of the State, of civil society, as well as the active support of international cooperation and the countries guaranteeing the process. In this way, the accords were presented as a first step to open the door to a considerable period of reforms during a score of at least twenty years, with the desire to build a stable and lasting peace.

In the spirit of the accords, it is clear there is a need for institutional coverage and an extension of welfare policies, the public administration, the political system and also opportunities for economic development. Overcoming the "causes" or "factors"1 that fuelled the internal armed confrontation for more than five decades implies the integration of the war territories into national life. How can this extension and integration be achieved? This question is one of the main dilemmas of public action in the coming decades. Public action can "take the State to the territory" as many affirm; or rather "build the State from the territory", as others defend; or, at long last, seek a right combination between the two ways of State construction, top-down and bottom-top.

The purpose of this text is to present the main vision of the territorial-based and equity-based approach enshrined in the accords signed at the Colón theatre since it answers the question of how to build the State in war territories characterised by its absence or notorious precariousness.2 The response given at the Colón to the dilemma of the integration of post-conflict regions into the nation must be assessed concerning the Colombian institutional environment. The institutional dimension is critical because although the Colón peace agreements were the result of a purely political exercise, the implementation of what has been signed will also have a strong institutional conditioning factor. That is why the dilemma of how to build the State in post-conflict regions must consider the tradition of programmes, institutions and customary practices within the public administration.

The answer given by the Colón agreements to this predicament is analysed regarding two institutional realities.3 On the one hand, concerning the main characteristics of previous national programmes formulated for targeted territories and populations (sections 2 and 3). On the other side, from the perspective of the general features of the decentralisation process and the functioning of the regional administration plan (section 4). In each case, it is examined whether the agreements continue with the 'centralist tradition' of bringing the State into the territory or if they intend to innovate and grant greater protagonism to local forces in order to build a local State, one that integrates better into the nation. The answer is complex.

As a national programme, the peace agreement continues the centralised trend. It seeks to achieve the goal of peace based on the old administrative scaffolding and previous institutional practices. On the other hand, in terms of the local implementation model, the agreement proposes to break several institutional traditions and formulates essential innovations to the decentralisation process. However, several characteristics of spatial planning will be an obstacle to the decentralised implementation of the accords (section 4).

How to facilitate the implementation of the territorial-based and equity-based approach of the accords is the question addressed in section 5. One option may be to group the 170 post-conflict municipalities into sub-intervention groups, based on specific common characteristics. The other option is to formulate strategies for each important post-conflict objective and its programmes, valid for all municipalities. A simple statistical exercise recommends not forming sub-groups of townships because the characteristics of them do not allow significant groupings. Finally, in section 6, a set of institutional challenges that should be subject to reforms are pointed out to smooth the path of the execution of the agreements from a territorial-based and equity-based approach

PROGRAMMES, STRUCTURES AND PROCESSES OF A TERRITORIAL-BASED AND EQUITY-BASED APPROACH TO PUBLIC POLICY

The end of the conflict will herald a new Chapter in our nation's history. It will be an opportunity to initiate a phase of transition that will contribute to greater territorial integration, greater social inclusion - especially of those who have existed on the fringes of development and have suffered from the conflict - and to strengthening our democracy, bringing it to all corners of the country and ensuring that social conflicts can be resolved through institutional channels, with full guarantees for those taking part in politics. (Gobierno Nacional & FARC-EP, 2016, pág. 6).

The preamble of the agreement announces the founding objective of peace: a territorial-based and equity-based approach that integrates the war territories, characterised by institutional abandonment, lacking in economic and social development, and with low political representation. Then, when reviewing the specific programmes agreed upon, the general commitment is they require a regional vocation, that is, to adjust to the characteristics of the population, the economy and the local social fabric.

To evaluate the importance of the territorial-based approach in the peace agreements, this section (2) analyses characteristics of previous national programmes and public administration practices while executing projects that target specific beneficiaries and regions. Three variables are taken into account: the formulation of the programmes, the structure that implements them and the characteristics of the implementation processes, particularly concerning the incidence of local beneficiaries. The subsequent section (3) contrasts these characteristics with what was agreed in the Havana agreements. The purpose of this is to find out whether the implementation is part of the State's tradition of intervention in the regions 'from top to bottom', or whether, on the contrary, for the sake of peace, it tries to build intervention programmes from the regions, or at least with their decisive participation.

Programmes

Programmes can be elaborated nationally and in a uniform way for all the territories, otherwise characterised as specific and of priority intervention. Programmatic centralism, through which consistent solutions are brought to targeted beneficiaries, is a deep-rooted tradition of almost all national programmes, destined to regions in a situation of economic crisis, severe disturbances of public order or that have suffered some natural catastrophe.

At the other end, there are programmes built locally by any combination of regional governments, social stakeholders, grassroots movements and the general population. There is no precedent for a national programme that, with funding and institutional and central political support, yields local institutions and communities the decision-making on the general orientation of the programmes and investments to be executed. However, some degrees of impact on projects, or at least some influence on priorities and specific characteristics of the goods and services offered by programmes with central guidelines, have not been alien to governmental interventions in selected territories. Since the National Rehabilitation Plan (Plan Nacional de Rehabilitación) in the eighties and some programmes and projects of the Social Solidarity Network (Red de Solidaridad Social) in the nineties,4 experiments have been done with such partial delegations (Barberena & Barros, 2014). Between normative and standardising centralism on one extreme and, on the other, total flexibility and programmatic autonomy, there is the cumulation of experiences of Colombian public policy, which inclines towards the central standardisation of programmes more than to the particularism of local solutions.

In this regard, the general tone of the Colón agreements, without any doubt, claims to tilt the scale towards greater local interference in the programmes of the Comprehensive Rural Reform (Reforma Rural Integral), the Development Programmes with a Territorial-Based Focus (PDET, in its Spanish acronym), and those for the substitution of crops used for illicit purposes.

Implementation Structure

The implementation structure is usually set by the highest levels of government, attached to the Office of the President or in the orbit of direct influence of the central executive power. The national programme for the territories is generally lead by an entity created for the occasion or ascribed to a ministry with some degree of autonomy and specialisation. From this occasional institutional and programmatic creation, the central power is deployed over the regions through the construction of a structure and a bureaucracy parallel to the structure of the customary public administration. Most of the time, the national fabric is organised by regions, whose directorates delegated from the centre cover several departments. From the thus created "regions of intervention", the parallel governmental bureaucracies make a roughly permanent presence, which floats intermittently over departments and municipalities.

In other cases, the central structure can also be directly anchored in the departments, and from there it deploys actions of municipal presence. The national programmes and structures for specific regions, although having its landing location at the municipalities, do not have the budgetary and institutional strength to guarantee robust local arrangements. These characteristics are recurrent in centralist programmes and structures with the intention of portraying a territorial-based and equity-based approach.

The alternative to the centralist tradition of the national programmes would be a decentralised structure, in which the regional administrations would have control over the bureaucracy and its processes, and over the state deployment in the territories. In this case, the packages of services offered can be determined in a centralised manner or concerted between levels of government or be part of the autonomous sphere of the local governments. In any case, the local bureaucracy and politicians would have the power to intermediate programmes and resource management between the nation and local beneficiaries. Undoubtedly, the decentralisation process, initiated in the 1980s, strengthened the decentralisation of the regional administrative structure.5

At the beginning of the process, many areas and functions for which budgets were assigned were part of a general package. Regional authorities had power to grant them degrees of priority and relative freedom in terms of management models for carrying out decentralised policies. However, since the first five years of the nineties, the momentum of decentralisation gradually began to decrease in two ways: a strictly regulated devolution of specific competencies declared as priorities and miriad central conditions on the management models of the local public administration. Thus, the decentralised public administration regained a strong bias from the regional arm of the central government, in terms of purposes, competencies, functions, processes and programmes locally executed (Restrepo, 2015).

The Colón agreements do not have the will to reverse the tendency of the territorial expansion from the Central State outwards, particularly in the early phases and years of institutional and programmatic creation. On the one hand, the peace agreement programmes are national, assigned to state authorities at the central level, where the "Agencies" are multiplied, many of which are attached to the Office of the President. Each agency is deployed over the territories based on a national programmatic and hierarchical command and tries to float6 over towns, municipalities and rural settlements (veredas),7 to undertake its specific policies: the protection of victims and the restitution of their rights (Victims Unit), territorial development programmes (Agency for the Renewal of the Territory), the protection and reincorporation of those who had formerly taken up arms (Agency for Reincorporation and Normalization) and land restitution (Land Restitution Unit). Even the coordination of the different agencies, programmes, ministries and entities of the national order in the territories is the responsibility of a central agency that, itself, glides across the departmental and municipal administrative structures (the Agency for the Renewal of the Territory).

Implementation Processes

The processes to implement the policies are found beyond the definition of the programmes and the leadership over the structures. The execution of public policies may be the power of bureaucracies at any national level. It can also be delegated to the civil society, in the form of the private business sector, or ethnic, peasant community organisations, or social organisations of any kind.8

Since the Comprehensive Rural Development programme in the 1970s, the State has invoked the participation of the beneficiaries (back then, the rural population) in the implementation of public policies. Subsequently, in the 1980s, the Plan Nacional de Rehabilitación, the Social Solidarity Network and the health sector, the call for "social participation" has been a central feature of the public policy implementation models. In the nineties, the hegemony of the neoliberal ideology enhanced the role of businesspeople and consumers, while criticising the intervention and the monopolies of the State and bureaucracies. The offer for participation did not diminish but spread even more. Social programmes targeting multiple vulnerable groups became the hook to involve beneficiaries in the execution of the programmes. At the same time, the private sector grew more involved in the implementation of anti-poverty policies, making the miserable and vulnerable a large expanding market, from the management of subsidised health insurance, through food policy, up to the education sector (Hurtado Mosquera, Hinestroza Cuesta, 2016).

The Colón agreements invoke the right and goodness of social participation in the many programmes announced, with several characteristics. Apropos of the first, the power of different social sectors to participate in the decision-making of the programmes to be implemented and the execution of works and the monitoring and control of the administration, resources and projects are defended. Concerning the second, the participation of the social sectors is mentioned in a generic way, but the social organisations that represent them are scarcely mentioned. Regarding the third, assistance is invoked in the instances and processes of the different programmes, but any strategy to promote the permanent participation of social organisations in the structures of local powers or in the administrative structures of the programmes and national agencies that implement the policies is omitted.

A fourth characteristic of the offered participation may become relevant to the general trends of recent decades: participatory planning. This one is a right enshrined in the Constitution of 1991, which also contemplates a National Planning System and the creation of Territorial Planning Councils at national, departmental and municipal levels, with the participation of representatives from different sectors of the society, to influence directly in the development plans. These councils suffer from multiple problems. First, as they have a representative nature, they limit the active participation of the population as a whole. Second, they do not always represent all sectors of society. Third, they do not necessarily function during the four-year term of government. And fourth, at the municipal level, they are not always created independently from the local government (Velásquez, 2010), (Velásquez & Gonzales, n.d.), (Fundación Foro Nacional por Colombia, 2016), and their very existence is a rarity, as their impact on public policies is scarce with a tendency to be null. These instances of participation, having a representative nature, have been extended to more and more numerous sectors: education, young people, the elderly, food, etc., bringing with them the same problems as those the Territorial Planning Councils have.

In the Colón agreements, the programmes of the Comprehensive Rural Reform and, particularly, the PDET and the programmes for the substitution of crops used for illicit purposes are based on effective participatory planning exercises. At least as agreed in the peace process, in the section dedicated to the recognition of the regions affected by violence, abandonment and precariousness, these territories are called to be definitive participants in the development agreements for their rural settlements, as well as in the implementation of the national programmes. The way this type of participation occurs, and the impact that it may have on the course of the policies, will be decisive for the success of these programmes.

THE TERRITORIAL-BASED AND EQUITY-BASED APPROACH IN THE COLÓN AGREEMENTS

In section 2, we analysed the general tendencies of national programmes that focus on territories and people, to contrast with the provisions of the Colón agreements in terms of programme formulation, the administrative structure and the implementation process. In this section (3), we complete the analysis of the Colón agreements as a national programme for peace, to know whether it will "bring the State to the territory", as has generally been done, or it strengthen the local construction of the State.

It is not surprising that different tensions, emphasis and nuances traverse an agreement as complex as that reached by the national government and the leadership of the FARC insurgency. However, a general tonality cuts across the whole of what has been agreed in terms of the territorial-based and equity-based approach of the policies to be carried out in the territories chosen to be intervened. In general terms, the "State will be brought to the territories" through sixteen basic programmes. These are national, as are the administrative and political command structures. Regional governments, especially Departments, are rarely mentioned, the mention of municipalities is slight, and there is no mention of a decentralisation process. Most references to territorial state materiality are made using the words vereda (rural settlement), town, territory or regional entity.

The relevant regional actors invoked are the different social groups, occasionally their organisations and not at all the social and organisational networks grouped by topics, regions or both. This amorphous and dispersed civil society is called to the instances and moments in which the projects are defined, within the mechanisms of the occasional and floating programmes and structures of the central level on the territories. The culminating exercise of an encounter between the State and the society is based on participatory planning, the founding process of the signed agreements that must be able to channel social demands and aspirations. Regional entities, specifically the municipalities more than the departments, are called to participate in the exercises of planning and discussing programmes, as one more actor, as part of the relatively undifferentiated landscape of multiple social sectors with local administrations. A more real call to the municipalities is accepted in the execution of decisions, and it is recognised as an acknowledgement to the ethnic communities and their organisations in the planning and implementation processes. On the other hand, the regional entities are called upon to participate actively in the co-financing of post-conflict costs.9 A conflictive situation is, thus, foreseen in which territorial authorities are subordinated parts in the structures and decisions of the post-conflict programmes, but they must contribute a good share of "their resources" to the financing of the programmes.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INSTITUTIONAL TERRITORIAL INTERWEAVING

The implementation of the peace agreement will also be conditioned by three characteristics of the architecture of the territorial structure: 1- Decentralisation, 2- Separation of the departmental and municipal level as regional self-contained areas, 3- Precariousness of the intermediate level (departments) and its inability to coordinate the policy sectors in its territory.

Decentralisation

The processes of political, fiscal and administrative decentralisation generated a significant inflexion in the centralist architecture of the political system, the intergovernmental finances and the regional architecture of public administration since 1986. On the positive side, the creation of a more pluralistic political system,10 a greater territorial extension of public expenditure and a recognised increase in the socio-territorial coverage of fundamental social policy, especially on health and education (both with 95% of coverage in 2016) and basic sanitation and drinking water (which coverage have grown to 90% and 77% respectively) (Velásquez, 1995; Bonnet, Pérez, Ayala, 2014). Also, noteworthy are the limitations of the scope of decentralisation, which acquire particular relevance in the face of the challenges posed by the implementation of the peace agreements. In different ways, what has been settled exceeds the limits of decentralisation, as well as poses challenges that are announced as necessary to face.

The thematic limit of the decentralisation is the social policy; however, the programmes announced in the Colón theatre intervene in the regions through decentralisation of economic development opportunities. In particular, the Comprehensive Rural Reform and the alternative programmes for the substitution of crops used for illicit purposes emphasise on communication and connectivity infrastructures, land allocation, credit, food production and marketing, farmers' markets, rural and urban progress, as well as on incentives to the associativity of the producers.

The second limit of decentralisation that is to be exceeded is the predominantly urban bias of the spatial reforms undertaken so far. Indeed, transfers, services coverage and social policies are concentrated in the town centres and their immediate surrounding areas (López and Núñez, 2007). While decentralisation has an anti-peasant bias, the peace agreement programmes are primarily oriented towards the countryside and its dispersed population, which was agreed to be supported through improved food production, commercialisation, credit, access to land, agricultural equipment procuracy, as well as in physical and electronic connectivity.

The third expected innovation of the peace accords to decentralisation is about the long-term participatory socio-territorial planning processes. Both the PDET's and the programmes for the substitution of crops used for illicit purposes would be agreed through popular assemblies with the inhabitants and the organisations of rural producers.

In contrast, until now, the decentralisation of social policy has been mainly present in the health and education sectors, each of which is subject to an abundant and strict central sectoral regulation. Even though mayors and governors must formulate development plans, which should be subject to participatory territorial planning, the rigidity of the primary sectoral conditions makes plans to become a list of specific executions of the General Transfer System (Sistema General de Participaciones). Thus, participatory planning in decentralised social sectors is practically non-existent. The second resource pool that finances the territorial policy comes from taxes levied on the exploitation of natural resources that feed a General System of Royalties. These funds are assigned to specific projects, presented by regional entities, in such a way that they have no obligation whatsoever to be part of a development plan, nor are they obliged to go through a participatory planning process, in which policies, programmes and projects are decided to be subject to citizen vigilance and control.

The fourth innovation of the peace agreements to decentralisation is the multi-scale dynamics of planning to establish with citizen participation the priorities of development. The planning takes place first in 11.000 rural settlements (not recognised as an administrative entity by the time) going through a cluster of 170 municipalities, and finished in 16 subregions across 19 departments. These subregions, characterised by common and dynamic problems that relate territories, their people and their administrations, are not part of the current political and administrative structure.

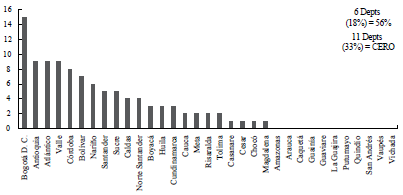

The fifth innovation is political, the representation of sixteen particular electoral constituencies from 167 municipalities would allow the inhabitants of the areas most affected by the armed confrontation to access the Congress of the Republic for two consecutive periods. In this way, an enormous limitation of political decentralisation, the under-representation of vast territories in the nation,11 is partially overcome. For example, on average, 11 departments lack senators, and six departments concentrate more than half of the country's congresspeople.

These five innovations of the Colón agreements complete the limitations of the decentralisation process and pose two significant difficulties. On the one hand, the whole of the conventional territorial structure (administrative, fiscal and political) remains intact, making it easy to foreshadow clashes of competencies between authorities and the typical processes customarily functioning within the State, including the specific programmes, instances and mechanisms set by the peace agreement. Secondly, while the regular structure of the State is maintained, the programmes and their parallel structures are highly dependent on future and uncertain regulations, the attainment of resources and a painful institutional construction.

On the other hand, it is to be expected that, in the eventuality that the implementation of the programmes advances positively, there will be increased pressure from many rural settlements and municipalities to be part of the post-conflict territories. After all, the four characteristics of the 170 towns are shared by an immense number of other places: poverty, violence, institutional precariousness and illegal economies. In this case, it can happen as it happened with the municipalities part of the National Rehabilitation Plan, whose list grew considerably with the passing of months and years.

Enormous parallel structures of intervention that extend into space and time end up creating mechanisms for transferring learnt lessons and models of public management from one side to the other. Since the nineties, special programmes to combat poverty, vulnerability, natural disasters and public order disturbances have been the seedbeds for innovation in general management. It is advisable to be attentive to the changes achieved by the PDET's and to the management models, structures and exceptional mechanisms that could be transferred to the regular administrative structure.

The peace agreements bring several more general enquiries about the decentralisation process. First, why not complete the decentralisation of the social policy with the devolution of economic development opportunities benefiting all the regions in the country? Second, why not reinforce effective citizen participation and assembly democracy, in terms of decentralised public spending? Third, why not condition transfers and royalties to real exercises of participatory planning? Fourth, why not consider the supra-municipal (rural settlements, veredas, provinces), sub-departmental (sub-regions) and supra-departmental (regions) scales as appropriate spheres for development planning? And, finally, why not extend the political representation of peasants in their municipalities and provinces; as well as improve the representation of the municipalities in the departments and latter in Congress? The deficit of political representation is not confined to the 16 selected sub-regions, but it is a general phenomenon of the electoral political system at the municipal, departmental and national levels.

Territorial Self-Contained Areas

A characteristic so generally criticised refers to laws that establish standard rights and duties for all territorial entities despite the different capacities, characteristics, needs and potentials of each municipality (Maldonado, 2018). The process of decentralisation of resources, competencies and political power has not managed to overcome this ancestral normative and institutional rigidity. Institutional uniformity is accompanied by the rigidity in the interaction of the State with its entities, and that is why we frequently resort to exceptional intervention mechanisms. Exceptionality becomes the rule to address the territory particularities creating a crisis, due to the incapacity of the administrative system to incorporate flexibility in its regular functioning12.

Departments and municipalities which are undifferentiated, in terms of rights and duties, end up being treated as self-contained and isolated areas, that is, as abstract entities. Concerning them, the mechanisms of coordination between national levels and the concurrence in processes and competitions are complicated to achieve. Each level is separated from the other, in such a way that it hardly concurs with the superior or inferior degree in constructive systemic relations. Paradoxically, the combination of institutional, programmatic and normative inflexibility with undifferentiated models of territorial intervention ends up isolating each territorial entity from its relationships with its peers and with the other levels.

There is nothing in the Colón accords that allows us to reflect on the importance of this difficulty and to innovate in this matter. The agreements do not deem permanent and systemic relations between the three levels of the State to be necessary for the design, administration and execution of the programmes. Rather, coordination is invoked so that the departments and municipalities do not come into conflict with the implementation of national post-conflict programmes.

The transfer of lessons learned from parallel and exceptional peace programmes to conventional territorial structures will find a more significant obstacle in this void: How to achieve a permanent strengthening of the capacities of local institutions and bureaucracies in this manifest absence of consideration for the specific reality of territorial entities in the post-conflict? The difficulty of strengthening local institutional capacities is greater since these entities are not called to participate organically in the programmes but are evoked as potential causes of conflict against the national peace programmes in their regions.

The Precariousness of the Intermediate Level and the Absence of Horizontal Interventions

The weakness of the departmental level in the decentralisation process has been widely studied (Estupiñán, 2012; Moreno Ospina, 2014). Departmental leaders have been claiming for tax reform for decades, denouncing the tax system is outdated since the end of the colonial period and the nineteenth century. The decentralisation process has privileged the municipalities and abandoned the pretension of building provinces and regions as full territorial entities, that is, with elected representatives, subjects of receiving funds from the national budget, with their resources and administrative autonomy.13 As a result of the above, there is a mainly municipal decentralisation, in which each municipality assumes its rights and duties in isolation, and accounts in different ways for national information and evaluation systems. In this institutional panorama, national decentralisation initiatives are scarce, although meritorious, in the quest for joining efforts among municipalities, between departments, or both to undertake multi-level public policies (Bustamante, 2014).

The Colón agreements do not address the issue of horizontal cooperation between territorial entities, nor do they consider the departmental level to be of any importance, although they mention the municipalities a little more. What is announced are programmes directed towards primary rural-level communities, over which the municipalities could exert some accompaniment, but the departments will not. To the extent that a good part of the programmes has an economic vocation, it is foreseen that the scope of eventual systems of territorial, economic development will be reached at a micro-territorial scale.

Thus, the beginning of the peace process has as its horizon an integration of small communities in micro territories into the State, in which they would be the beneficiaries and participants of social and economic programmes. The inclusion of large regions to the nation, to its political system, infrastructures and markets, would have to have other economic and institutional development programmes with greater coverage than those foreseen in the peace agreements. If this were to be considered, the provincial, departmental and regional levels would be required to have a predominant place in the planning and execution of projects, absent in the Colón agreements.

POST-CONFLICT TERRITORIES

The concern addressed in this section has to do with the nature of the implementation of the Colón agreements in the prioritised territories, in such a way that we wonder whether the post-conflict programmes should be implemented in the same way across the 170 municipalities prioritised for intervention on the peace agreement. There are two options: the first, 3 or 4 municipal categories could be established that would guide the specific integration of the sixteen programmes agreed upon in the territories thus differentiated. The second option is to recognise specific essential features that distinguish, in each case, clusters of municipalities. For this second option, it is not a matter of identifying single municipal subgroups of intervention, but of establishing intervention strategies with enough flexibility to be adapted to the territorial specificities. The exercise explained below concludes in favour of the second option.

The Selected Municipalities

"The peace agreements contemplate the creation of Development Plans with a Territorial Approach with the objective of achieving "the structural transformation of the countryside and the rural environment and to promote an equitable relationship between rural and urban areas" (Gobierno Nacional & FARC-EP, 2016, page 22). The agreement defines four criteria for prioritising post-conflict territories: poverty levels, the degree of affectation derived from the conflict, institutional weakness and management capacity, and the presence of illegal economies.

Development Programmes with a Territorial-Based Focus are one of the most ambitious bets of the peace agreements, as they seek the economic and social transformation of those areas that have been most affected by violence and abandoned by the State. It is expected that they will become instruments for long-term planning, that they will be built based on local and municipal visions, with the aim of generating sub-regional development visions. In addition to the PDETs, post-conflict municipalities will be the centre of many programmes created by national authorities and international cooperation organisations, aimed at the strengthening of municipal institutions and their social and producer organisations.

Following the Decree 893 of 2017, which creates the PDET, a series of variables that represent the dimensions described by the agreement were defined. First, to measure poverty, the multidimensional poverty index was used. In the case of violence, two components were used: the first considers the variables of armed confrontation (actions of criminal groups and Military Forces), while the second refers to the variables of victimisation (homicide, kidnapping, massacres, dispossessions, displacement, anti-personnel landmine victims, forced disappearance and assassinations of trade unionists, local authorities, journalists and land claimants). For the variable of illegal economies, there were used the hectares of coca crops, a vulnerability index and the illicit exploitation of minerals, as well as smuggling. The fourth variable is the institutional weakness, for which the gap methodology of the National Planning Department -DNP- was used.

By crisscrossing the four previous variables, it was possible to identify the municipalities most affected by the armed conflict. Then, to create the 16 sub-regions, some municipalities contiguous to the previous ones were included, thus creating geographically continuous sub-regions. In total, 170 municipalities were chosen and distributed in 16 sub-regions, where the PDETs will be implemented.

Possible Variables to Distinguish Differentiated Strategies

The municipalities most affected by the conflict share a series of characteristics and complexities relevant to the implementation of the peace agreement policies and programmes. In this section, we are going to examine the aspects of the 170 PDET municipalities to identify the best way to implement in them the post conflict policies.

As explained in section 2.a, the implementation of the Peace Agreement can follow the Programmatic centralism, i.e. it can be designed from the centre to be applied to a set of territories that are presumed to be similar. Or, programmes can be built locally by any combination of regional governments, institutions and territorial entities, social stakeholders, grassroots movements and the general population. The analysis of the characterisation of the 170 municipalities will allow us to respond to this dilemma14.

To achieve this objective, six variables that are key to determining the homogeneity, or not, of such territories will be analysed. These variables were chosen based on the availability of information (it is difficult to obtain statistics at the municipal level) and because of their relationship with the public policies that will be implemented in the post-agreement and that will be aimed at strengthening municipalities, boosting local economies, especially the rural sector, and improving the provision of public services.

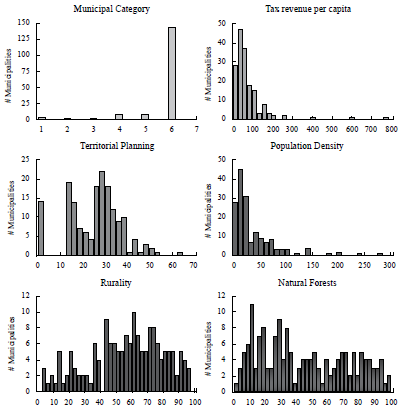

In the first place, we review the tax categories that classify municipalities in Colombia according to their population and tax revenues. In general terms, this category is not very useful insofar as 89% of the country's municipalities are in class 6; that is, they have a tiny population or very few resources, or both. In the case of PDETs, it should be noted that most of the municipalities (146 in total) belong to the sixth category, according to the traditional division. Thus, the conventional classification of municipalities is not very useful for reviewing the characteristics of PDET's municipalities.

In the second place, we are going to review the average tax income per capita of post-conflict municipalities, this variable is an indicator of institutional development of every single town, to the extent that municipal tax collection depends on the capacity of municipalities to collect them (taxes and their rates are the same in all municipalities). The per capita tax income of post-conflict municipalities is 76 Colombian pesos, which is much lower than the national municipal average of 129.4. However, according to Annex 1, a few municipalities, 25 in total, have a high tax collection, above the national average, while the majority, in total 97, have a meagre tax collection, equivalent to 63 Colombian pesos or less, and 45 municipalities have a low tax collection, lower than the national average. Thus, in general terms, post-conflict municipalities are characterised by low per capita income. However, about 15% of them will not require help to improve their tax collection.

In third place, spatial planning is revised by the variable of the same name provided by the new Municipal Performance Measurement from the DNP, which includes the efficiency of property tax collection (effective collection rate) and the number of instruments used in it (DNP, 2017). This variable gives us an idea of the Development of the municipalities in issues of spatial and land-use planning.

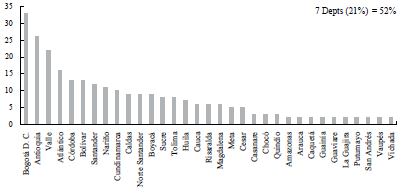

On average, the municipalities of the country have a spatial planning indicator of 31.1 points, while post-conflict municipalities obtain a score of 25 points, so that, in general terms, these municipalities have low cadastral management in contrast to the rest of the country. In this indicator, it is possible to differentiate three groups within post-conflict municipalities: 55 territories have a low spatial planning indicator (from 23 to 31 points), 63 have a shallow index (from 0 to 23 points), and 48 have an average rating (more than 31 points). Which shows a great diversity in terms of municipal territorial ordering (see Annexe 1).

In fourth place, we consider the population density. This variable gives us an idea of the structure of the municipality and its needs since those municipalities with the most dispersed population will require more significant financial and institutional efforts to cover their entire community in post-conflict programmes. Post-conflict municipalities have a (low) concentration of 39 people per square kilometre on average, while the national average is 149 (Annex 1). Only one group, mainly small cities, do not present limitations in terms of population density. So, in general terms, the postconflict municipalities have a low population density.

In fifth place, we examined rurality, approximated by the percentage of the population that does not live in the town centres. In general terms, the behaviour is similar for the post-conflict territories and the national aggregate. However, in post-conflict municipalities, the distribution of this variable allows the formation of three groups: 1- Urban, which corresponds to 25% of the towns where 43% of the population or less does not live in the town centre. 2- Intermediate, equivalent to 42% of the municipalities, where between 43% and 70% of the population does not live in the town centre. 3- Rural, which represent 33% of the municipalities, where more than 70% of its population does not live in the town centre. In this case, the second and third groups should have programmes and structures for rural development, especially in agriculture.

Finally, we consider the natural forest like a proxy to environmental conditions, a variable that is key to sustainable development. The diversity of post-conflict municipalities is also evident in this variable, as 44% of municipalities have a natural forest cover lower than 34% of their territory; while 28% have a layer that covers between 34% and 66% of their areas. In 28% of the remaining municipalities, the natural forest cover represents more than 66% of their territory.

In the five variables considered (tax revenues, territorial ordering, population density, rurality and natural forests), the distribution of the municipalities does not allow them to be treated as a homogeneous group15, i.e., despite the fact that post-conflict municipalities share the same definition (violence, poverty, illicit economies and institutional weakness), the main characteristic of these regions is their internal diversity.

The five variables presented do not have a strong correlation with each other (the correlation coefficients are less than 0.5, see Annex 2), so it is not possible to generate groups of municipalities that share the same characteristics. What is suggested to do, on the contrary, is to respect the heterogeneity of the post-conflict territories, with the generation of particular policies with enough flexibility to adapt them to these specificities. This exercise is an example of the need to break with the traditional territorial self-contained areas and the necessity to legislate on heterogeneity.

For example, in the case of natural forests, those municipalities that have higher coverage and greater biological diversity could be identified with the objective of prioritising those strategies that will not destroy nature (ecological tourism or sustainable agriculture), in an attempt to close the agricultural frontier.

In terms of per capita tax revenue and spatial planning, priority should be given to strengthening the institutional tax framework of the municipalities that have shown the worst results in these variables, which would allow improving their institutionality by providing them with greater free income.

Finally, rurality and the dispersion of the population are critical factors for the elaboration of the visions and objectives of the PDET. The possibility of generating divisions within more extensive, more rural and more dispersed municipalities could be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

This document has reviewed the territorial content of the Colón Accords in search of the innovations they entail for decentralisation and relations between government levels. The characteristics of the Colombian State were reviewed in territorial terms, in such a way that the type of programmes, their structure and their implementation processes were investigated. The construction of programmes from the national level and executed from national governmental structures, but with citizen participation for their design, is the main character that has exhibited the intervention in the territories so far. The Colón Accords mostly follow this characteristic.

However, the Peace Accords contain five innovations related to decentralisation: economic decentralisation, pro-rural bias, long-term participatory socio-territorial planning processes, multi-scale dynamics, political devolution (with the allocation of seats in the Congress to post-conflict territories). The concerns generated by the agreement given the precariousness of the middle level of government and the coordination between levels of government are highlighted.

To conclude, an exercise on the 170 PDETs municipalities, which will be the primary recipients of the implementation of the Agreement, shows their heterogeneity that contrast with the traditional forms of territorial intervention of the State.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The to-do list in public policy for the implementation of the peace agreements is enormous and contains many fronts, of which here we have privileged some critical aspects referred to the territorial construction of peace. The analysis of the trends detected in the Colón agreements and at the beginning of the implementation was complemented with considerations on the practices of large programmes for territories, populations and specific problems, in addition to evaluating the state of the decentralisation in the face of what was agreed.

In politics, everything cannot be done at the same time, nor must it be done at the same time. In peacebuilding, the first thing to do was agree on disarmament and political rights to ex-combatants, transitional justice, programmes for the regions most affected by violence and establish principles for the substitution of illegal crops. What follows, among other priority issues, is the construction of strategies for the implementation of special programmes for priority intervention territories. Here, we point out six reform challenges that would support the implementation of the peace agreements and are not foreseen in the signed peace accord.

Strengthening Local Institutional Capacities

The strengthening of local institutional capacities is an irreplaceable possibility for the construction of a "stable and lasting" peace. If territorial governments and their institutions are marginalised from the calls, the direction of the processes, participatory planning and the execution of projects, the desired strengthening of local capacities will not materialize. Who is responsible for this decision? Without a doubt, the best option would be a general orientation in this regard from the sources of financing and the formulation of the programmes. Later, much will be defined in the design of the structures and processes of execution of programmes and projects, which will blur the responsibility in the different policy sectors that will intervene.

In this regard, the Territorial Renewal Agency (ART, in Spanish) will have primary responsibility in promoting or omitting a strategy to strengthen local institutional capacities. The ART is the agency designated to coordinate the different national sectors in the territories and to accompany the PDETs. The agency can deliberately incorporate the institutional strengthening of municipalities into its objectives and processes, which would require financial resources and a precise and concrete political mandate. It would be convenient if each sector that intervenes in the execution of programmes and projects is legally compelled to submit to the ART management model, in the sense of promoting regional coordination and participatory planning. In practical terms, and as an example, the obligation could be created by conditioning the funds received by national sectoral entities to their engagement in spatial planning processes. To the same end, the ART management model could indicate the components of local institutional strengthening that correspond to each sector and programme that is executed.

Creation of Community Institutions

The characteristics of the municipalities prioritised in the post-conflict are poverty, violence, institutional precariousness, illegal economies, illegal mining, coca production and smuggling, low population density and dispersion, the devastation of nature, lower incomes for people and municipalities, and the primacy of rura-lity. None of these factors can be overcome in a "stable and lasting" manner with foreign interventions that do not build approachable institutions. The rural settlement (vereda) figure must be exalted and strengthened from the legal, economic and political point of view. On the other hand, grassroots social organisations must be recognised to agree on projects and guidelines for territorial planning. Besides, administrative and political functions could be assigned to the social spokespersons, thus, building a local administration from the grassroots social fabric.

The Strengthening of Local Bureaucracies

There are no strong institutions without enough officials, subjects of continuous training in skills and competencies, who enjoy stability. Job flexibility and instability in public administration is a permanent source of wasted skills and know-ledge. It is the responsibility of the Ministry of Labour to move towards greater stability of public employees and the Public Function, in association with the School of Public Administration, to implement a long-term programme in the training of civil officers and social leaders of prioritised municipalities. Needless to say, human rights training for civil officers is imperative in these regions, but also in the entire national public administration, as well as in social organisations and foundations implementing public policies on behalf of the State.

Building a Web of Intergovernmental Relations

Intergovernmental relations are very weakly stated in the Colón agreements to the point that it is not an exaggeration to highlight the total lack of foresight about how the ties between the nation, the departments and the municipalities will work during the implementation of the programmes. Every void tends to be filled in some way or another, and this will be done based on the practices that each sector is accustomed to implementing, that is to say, centralised, dispersed and discontinuous practices without a regional approach.

It is therefore urgent in the post-conflict to build a strategic and normative framework to encourage and regulate intergovernmental relations. Also, national programmes should be implemented with the participation of local administrations; in such a way that their capacities for policy execution are strengthened. The responsibility of such an initiative lies, as long as it exists, in the Presidential High Advisory for the Post-Conflict, which should agree on the strengthening of intergovernmental relations for the coming years with the territorial guilds, as well as with governors and mayors from those regions.

Relationships between rural and Municipal Participatory Planning

In post-conflict territories, rural and municipal planning, special sectoral programmes with a territorial vocation and customary sectorial interventions will coincide. Coordination among sectors and agreement among all levels of government will then be an unavoidable necessity that will bring frictions and contradictions requiring great leadership and processing mechanisms to be solved. Until now, the Territorial Renewal Agency has the "technical" responsibility in this matter, but as strong as the agency will become, it will require the political protagonism of territorial leaders. A Round-table for Territorial Articulation is planned as an instance of articulation between regional entities and elected representatives. It will have to formulate policies, follow up and recommend adjustments for the territorial articulation between rural and municipal processes and of these with the departmental ones.

Definition of the Intermediate Level Functions

The departments are the 'missing link' of the articulation between the nation and the municipalities, so that, in the absence of a strategic departmental function, the initiative that each public sector performs on its own in the territories, without coordinating with other areas in each department, prevails. The Colón agreements do not surpass this situation at all. The National Federation of Departments should take the initiative to gather agencies, entities and think tanks to formulate policies that define the functions of the departments during the post-conflict times.