INTRODUCTION

In 2012, Enrique Peña Nieto was elected President, which meant the return of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) to power after more than a decade in opposition. Ever since his campaign, he had pointed out the economy's slow long-term growth and the acute poverty as the major challenges -perhaps the greatest- of Mexico's development agenda. On his first day in office, along with the leaders of the three main political parties at that time, the PRI, the Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN), and the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), he launched the Pacto por México (Pacto). This was officially described as "...a new political agreement to boost economic growth and generate quality jobs demanded by Mexicans" (López-Noriega & Velázquez, 2018, p. 46).

The Pacto, Mexico's most relevant political agreement in a long time, identified 108 policy actions to be implemented between 2012-18. It also inaugurated a new wave of market reforms, along the same lines of the first reforms during the mid 1980s that opened domestic markets, reduced the role of the State in the economy, and made exports the engines of economic expansion. Comprising eleven reforms, the Pacto endeavoured to change key areas of the country's economic and social life: education, finance, energy (including oil and electricity), telecommunications, market competition, fiscal reform, transparency, and even the criminal justice and electoral systems. In addition, a liberal labour reform was put into operation in the last months of President Calderón's tenure (2006-12). All eleven reforms were implemented within the next 24 months.

The purpose of this paper is to make an overall assessment of this reform package with regards to its impact on removing -or not- key binding constraints on Mexico's log-term development. It is organized as follows: After the introduction, the next section reflects on the methodological difficulties inherent in assessing the impact of major packages of diverse structural reforms, given their multiple objectives and varied time horizons. Once the analytical underpinnings have been reviewed, a comprehensive assessment is made of the structural reform package as a whole (not of each reform individually) based on what we see as its progress and setbacks in promoting the country's economic growth and development. Subsequently, the paper comments on what we see as the new and the old challenges that the Mexican economy faced at the end of the Peña Nieto administration. This helps to explain the collapse of the PRI in the 2018 Presidential election and its defeat by López Obrador and MORENA, with their campaign focused on the need to fight corruption and to put an end to neoliberalism. We close with a brief analysis of the macroeconomic policies put in place by Andres Manuel during his first year in office.

ON THE IMPACT OF STRUCTURAL REFORMS IN MEXICO: AN OVERVIEW AND METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES

Peña Nieto's market reforms -in compliance with the regulations set by the State's economic planning responsibilities- were designed and launched within the overall framework set by The National Development Plan 2013-2018. The NDP identified five main axes in its development agenda: i) Institutional strength for peace, ii) Social development for inclusion, iii) Human capital for quality education, iv) Equal opportunities, and v) An international role with global responsibility. It included a Programme for Democratic Productivity (PDP) as an across-the-board initiative, arguing that ".. .in order for Mexico to fulfil its maximum potential it is indispensable to raise productivity (Gobierno de la República, 2013, p. 19). Moreover, it stated that:

The dynamism of productivity has been a recurrent feature of international success stories. Countries that have established the conditions for sustained productivity growth have been able to generate greater wealth and wellbe-ing for their people...Productivity in an economy is one of the fundamental determinants of economic growth. Growth is the means that will allow us to achieve a better standard of living for the population, a more equitable society and permanently reduce poverty.

In the negotiation process with Congress, Peña Nieto promised that the Pacto's reforms guaranteed a 5% annual average rate of long-term GDP growth. He warned that, without it, the average annual GDP growth rate would be 3% at most. The reforms defined the economic agenda of his administration. Macro-economic policy, which has been the same since the mid-1980s, focused on the objective of consolidating stabilization, understood as low inflation (around a 3% annual increase rate in consumer prices) and a minimal fiscal deficit. However, this has to deal with major external shocks in the oil international market as well as, and importantly, with the adverse effects of Trump's rise to power. Social policy continued to focus on conditional cash transfers to the poorest members of society.

On the economic and social fronts, Peña Nieto's reforms do not look to have been successful. The average growth of real GDP between 2012-18 was slightly above 2%. Total Factor Productivity actually declined, the incidence of poverty was higher at the end of his mandate than at the beginning, and inequality was not reduced. Formal employment, measured by the number of workers affiliated to Mexico's Social Security (IMSS) rose, but labour market conditions dramatically deteriorated: the unemployed plus underemployment and those who no longer seek work because they do not believe they can find it reached 20% of the working age population. The proportion of workers who receive less than three minimum wages rapid and persistently rose, while the share of those earning more than five minimum wages collapsed (Samaniego, 2018).

To a large extent, the Pacto followed the prescriptions of the pioneering market reforms launched in the mid-1980s by De la Madrid and Salinas de Gortari. However, it now took for granted that, after years of orthodox policies, the country's macroeconomic fundamentals were strongly consolidated. This is because a Pacto that boosted economic growth required a change in the supply conditions to favour the free action of market forces to jumpstart productivity. In its demand management, macroeconomic policy or even State-led industrial policies would and could not strengthen Mexico's long-term growth potential. Through supplying side interventions, this meant that distortions needed to be corrected for key markets to function. This was particularly true for the labour market, which was rigid, had poor training of human resources, was highly informal and, therefore, had a low productivity (Delajara, De la Torre, Díaz-Infante & Velez, 2018). An additional diagnosis was that privatization and deregulation has to be speeded up, mainly in the oil and electricity industries, financial services, and telecommunications industries. Removing the above-mentioned distortions would -the story went- boost productivity and growth. In terms of his individual reforms, in his last months in office Calderon (2006-12) implemented a constitutional change aimed at making the firing and hiring procedures more flexible.1 The following Table 1 summarises the reform package implemented during Peña Nieto's administration.

Table 1 Description of Mexico's Sstructural Reforms: 2013-2018

| Reform | Approval of secondary law | Key objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Labour | 08/2019 | Promote the creation of formal jobs through new and more flexible forms of employment with access to social security. |

| Educational | 09/2013 | Transform the national education system, focusing on teacher evaluation. Regain control by the State of public schools' payroll as well as their hiring capacities. The General Education Act and the Professional Teaching Service Act were enacted. |

| Fiscal | 10/2013 | Increase tax revenues by two and a half GDP points through changes in income tax rates, raise the maximum marginal rate to 35%, reduce investment tax incentives, and approve a 10% tax on capital gains and dividends. |

| Financial | 01/2014 | Strengthen property rights of creditors and empower the regulatory authority to expedite conflict resolution and competition between financial intermediaries. Expand capacity of development banks to provide credit to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). |

| Competition | 05/2014 | Strengthen the capacities and powers of the Federal Economic Competition Commission (COFECE) and give it constitutional autonomy with the power to eliminate barriers to competition and to regulate access to essential inputs. |

| Telecommunications | 06/2014 | Expand competition and create a regulatory body: Federal Telecom Institute (IFETEL) to sanction "dominant operators". |

| Energy | 08/2014 | Open the sector to the participation of the domestic and foreign private sector in terms of exploration, production, and transportation of oil and gas; as well as its refining and marketing, promoting competition, increasing technological efficiency, and the supplying of services. Modify the corporate governance structure of PEMEX and CFE. |

Source: Moreno-Brid, Sánchez and Salat (2018, p. 64).

Interestingly, even though Peña Nieto's discourse was in full favour of reducing the role of the State, the reforms of the educational, fiscal, and financial systems incorporated certain initiatives aimed at strengthening the public's certain regulatory capacities. The fiscal reform was set to raise public revenues by taxing higher socio-economic strata and removing important tax deductions. The financial reform -in theory though much less in practice- aimed to boost the intermediation of funds from the banking sector to be used in entrepreneurial purposes. The purpose of one relating to education was to recover the key role of the State in the administration of all matters related to public education (Granados Roldán, 2018).

A Note on the Methodology to Assess Systemic Reforms

The evaluation of any package of numerous, in-depth, and simultaneously applied structural reforms is a complicated task. This is especially true in this case where very little time has elapsed since their launch, and many of them were drastically interrupted by the new administration. A priori, there is a great diversity of criteria to evaluate them: almost as many as the different economic and social development objectives. The selection of any evaluation metrics is far from trivial. It may be that from the perspective of a particular goal, for example the sustain-ability of public finances, one reform may be seen as most favourable, but under another perspective (boosting public investment in infrastructure) it may appear to be a complete failure. Moreover, the design and implementation of the 2012-2018 structural reforms did not take methodological issues into consideration future impact evaluation.

A further complication is that progress of the different structural reforms towards their goals is not necessarily linear; its success or failure may perhaps only be accurately seen in the medium- or long-term. At the same time, a commensura-tion of the significance of its various effects is additionally complicated by the fact that many reforms were simultaneously applied with ambitious scopes that were not necessarily convergent. They may have impacted different areas of economic activity, heterogeneous populations, regions, or even social, economic, and political groups. The impact of external shocks also needs to be considered.

It should also be kept in mind that progress in achieving some objectives may lead to setbacks in others. These trade-offs can be considerable and policy-makers are not always aware of all of them or of the magnitude of their various effects on different groups. Likewise, any structural reform creates winners and losers. Last but not least, the implementation of structural reforms took place in a weak institutional economic planning framework. This made it more difficult to ensure its coordinated implementation, systematic monitoring, and regular evaluation.2

As López Noriega & Velázquez (2018) pointed out:

The parties in opposition, who shared the authorship of the Pact for Mexico and its reforms, neglected its monitoring and scrutiny. Once the reforms were approved, they forgot about their implementation and assessment... While the preparation of this agreement shone for its political effectiveness, the task of carefully following its execution stood out for its irrelevance. Actually many commitments that made up the Pact were simply ignored in practice (p.32).

An alternative option is through a counterfactual exercise in which the observed evolution of the economy from the implementation of the public policy in question is contrasted with what, it can be assumed, would have been its inertial trajectory in the absence of such policy. This methodology, however, is impossible to apply in the case of a such large-scale package of structural reforms like the Pacto.

Thus, any evaluation of the reforms and the Pacto por Mexico is subject to many caveats/assumptions. We chose to evaluate the joint package of structural reforms from two complementing points of view. The first is to focus on the extent to which the reforms achieved the objectives stated by the Peña Nieto government when they were launched as part of the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2013-18 and the Pacto. Were the goals achieved? The second evaluation is rooted in recent contributions we made with a dear colleague (Jaime Ros) involving the identification of binding constraints on Mexico's long-term growth. In this regard, we assess the degree to which the package of structural reforms weakened, removed, or sharpened key constraints on Mexico's long-term economic expansion.

THE MARKET REFORM PACKAGE 2013-18: AN IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS AND IMPACT EVALUATION

As part of his campaign, Peña Nieto recognised the urgent need to remove the Mexican economy from the trap of slow growth and acute poverty, despite having consolidated a dynamic export sector, a low inflation, and a very moderate fiscal deficit. He announced that his government would implement a set of major market-reforms to boost GDP, productivity, and employment. Some of these reforms, such as the one on telecommunications, had remarkable success, others did not.

Moving fast-forward to our main conclusion: from 2013-18, years during which Pacto's market reform package was intensely applied, the Mexican economy did not manage to get out of the trap of slow expansion. Undeniably, there were improvements in some indicators of well-being, for example, in life expectancy, school coverage, and child health. Likewise, low inflation, a limited fiscal deficit, and a booming manufacturing export sector marked the economy's performance. Moreover, the national elections were held peacefully and opened the door for the arrival of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party -and Andrés Manuel- to the Presidency. However, no significant progress was made in removing key obstacles to the country's development. The average annual rate of growth of real GDP was barely over 2%. Poverty, inequality, and lack of social mobility worsened. The labour market deteriorated with a recomposition of employment towards lower wage scales, and there was a reduction of labour earnings in real terms as well as a share of GDP. Labour productivity was far from dynamic and kept lagging behind that of the USA. Total factor productivity declined, contrary to NDP 2013-18 projections. To add to this poor economic performance, the rise in the perception of corruption, and growing concerns about insecurity and violence, the "remains-of-the-day" after the reforms did not turn out well.

To what extent are the disappointing results of the structural reforms due to errors in their diagnosis of problems with the Mexican economy? To what extent are they rooted in errors of instrumentation? Or are they rooted in, say, the bad-luck of adverse external shocks experienced in this period? To begin to answer this, let us return to the economic history of Mexico. As Moreno-Brid and Ros (2010) point out, the long periods of high and sustained expansion of the Mexican economy (1954-1970 and 1975-1982) were characterized by a strong and legitimate government that had a: i) Correct diagnosis of the binding constraints on the long-term growth of GDP, ii) Public policy tools able to remove or significantly alleviate such constraints and, most relevantly, iii) Capacity to build a consensus among the relevant political and economic actors on the two previous points and a shared and firm commitment to a viable strategy to remove them in order to boost economic growth and development. These conditions were simply not satisfied during Peña Nieto's tenure; thus, his reforms were ultimately doomed. This warrants a closer examination.

The reforms were based on the assumption that the country's macroeconomic fundamentals were solid and, therefore, only needed some adjustments at the micro level to remove market distortions. Based on this view, rising productivity would be a consequence of reduced labour informality and increased competition in local markets. It should be noted that boosting fixed capital formation and implementing an active industrial development policy were not involved in this diagnosis.3 The external sector was still seen as the engine of growth, and the internal market's potential to act as a complementary engine of expansion was assumed away or ignored. Wages were seen more as a cost than as a source of domestic demand. Not surprisingly, neither inequality nor lack of social mobility were social policy concerns.

Official speeches argued in favour of going beyond stabilization and trade liberalization and applying active industrial and financial policies to boost innovation and value-added generation (not low wages) as the basis of Mexico's international competitiveness. However, this discourse was not translated into effective programmes on a national level. Without such policies and in a context in which investment lacked dynamism, the Mexican economy could neither reduce its lags in productivity and sectoral heterogeneities nor trigger an upturn in economic activity.

The emphasis on micro or institutional aspects was, in our view, incorrect. It failed to tackle any of the binding constraints on the Mexican economy's long-term growth: i) insufficient fixed capital formation, especially in the public sector, ii) a productive domestic structure with weak upward or backward linkages. Thus, in spite of or because of the set of market reforms, our international competitiveness came more and more to be based on low wages and on imported intermediate inputs and capital goods, making the balance of payments an even more binding constraint on the long-term expansion, (iii) a financial system that does not provide adequate and sufficient resources for business activity, (iv) acute inequality and low social mobility (in addition to poverty) that undermines the potential of the internal market to act as an engine of growth, and (v) acute fiscal fragility, with insufficient resources, little impact on redistribution, countercyclical policies, and insufficient, and in many cases, inefficient public expenditure. Given that the Pacto failed to address them, these restrictions became more entrenched. To begin to remove them requires a different development agenda: one that is very different from the Pacto's structural reforms

In terms of economic performance, during Peña Nieto's tenure, the average GDP growth rate actually declined, and did not even reach 3%. Mexico was stagnant in terms of expansion. Mexico's gap with the United States in terms of GDP per capita and average labour productivity in these years continued to deteriorate relatively. Today, this GDP per capita gap is as broad as it was in the 1950s (Moreno-Brid & Dutrenit, 2018).

The persistently slow expansion of real GDP, for decades, is cause for alarm. An annual increase of real GDP below 4% per year is insufficient to create jobs for the growing workforce. A virtually stagnant economy, which is the current situation (in 2019 its GDP declined), cannot offer serious jobs and wages.

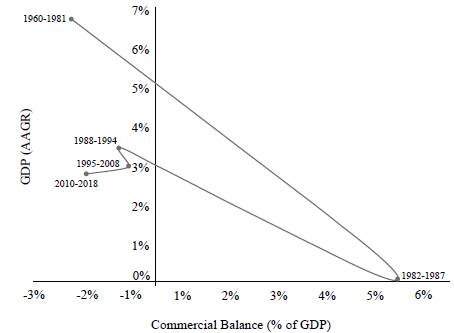

Figure 1 illustrates the weight of external constraint on Mexico's long-term economic growth. Note the deteriorating relationship between the trade deficit (as a percentage of GDP) and GDP growth rates since the debt crisis and the implementation of the first market reforms launched in the 1980s. During 1960-1981, real GDP grew at an average annual rate of 6.6% with a trade deficit equivalent to 1.7% of GDP. The end of the oil boom in 1981-82 and the subsequent crisis caused the economy to stagnate over the next five years and to register a trade surplus (on average 5% of GDP).

Note: TMCA = average annual growth rate, in percentages Source: Own elaboration, based on World Bank, World Development Indicators database.

Figure 1 Mexico's Average Annual GDP Growth and Trade Balance of Goods and Services

With trade liberalization underway from 1988-1994, and in 1995-2008 with NAFTA in operation until the international financial crisis detonated, real GDP growth averaged between 3% and 4% per year with a trade deficit close to 1% of GDP. Leaving aside the contraction in 2009, between 2010-2018 economic growth slowed down even more but the trade deficit increased as a percentage of GDP. In other words, without a change in the productive structure to significantly increase the internal backward and forward linkages, the Mexican economy cannot grow at high and sustained rates for a long period because the trade deficit would rise to unsustainable levels as a proportion of GDP, triggering a balance-of-payments crisis.

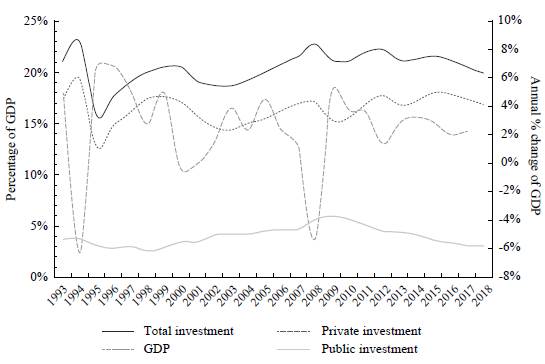

The failure of the export-led growth strategy that was inaugurated in the mid-1980s and continued until 2018 can be explained in several ways. The first is the lack of dynamism of gross fixed capital formation. The second is the acute increase in the income-elasticity of imports due in part to the absence of an industrial policy and in part to the long-term trend of real exchange rate appreciation. As the figure shows, despite structural reforms, in 2012-18 the fixed investment ratio as a share of GDP tended to decline. It remained below 25%, a proportion that the consensus marks as the minimum threshold to achieve GDP annual expansion rates of 5% or more. In addition to the concern about the limited momentum of investment, there is also evidence that its efficiency has fallen, as measured by the evolution of the incremental capital-output radio (ICOR) or by its multiplier impact on GDP (Moreno-Brid, Perez-Benitez, & Villarreal-Paez, 2017).

The trajectory of the investment ratio is explained by the fact that the upturn in its private component has been offset by the retrenchment of public investment. In 2012-18 -as in other presidential periods- any attempts for fiscal adjustment were concentrated on cutting spending on the public sector's fixed capital formation. This was politically much more feasible than cutting employment or wages in the public sector.

Source: Own elaboration, based on INEGI, System of National Accounts database (2019a).

Figure 2 GDP Growth and Gross Fixed Investment Ratios, 1993-2018, Based on 2013 Constant Peso Data

This strategy undermined private investment given the prevalence of crowding-in effects (not crowding-out as previously argued). Private investment has been held back by credit rationing by the private banking system and the lack of public development banks. Financial intermediation to the private entrepreneurial sector has been insufficient; it has a ratio as a proportion of GDP that is among the lowest for a large Latin American economy.

Indeed, in spite of the 2014 financial reform, the objectives of which were to foster competition in the commercial banking sector and strengthen development banks, the performance indicators of the system as a source of funds scantly changed. Domestic credit to the non-financial private sector remained below 18% of GDP. Development bank financing barely rose; thus, it remained very low compared to other international examples.

The lack of long-term venture capital was a strong barrier. Together with the financial reform, the intermediation margin with respect to interest rates (TIIE and CETES at 91 days and 182 days) fell by just two points. This was a likely reflection of the high concentration of the banking sector: 80% of total credit is currently concentrated in seven institutions. As we previously stated, when analysing of the macroeconomic implications of Peña Nieto's financial reform: "...except for very specific issues such as the rise in commercial banks' profits, [the financial reform] can be unambiguously described as a failure" (Moreno-Brid et al., 2018).

Strengthening the functionality of the education system is indispensable, in every aspect, from planning at all levels, administration, training, teaching and learning techniques/skills, materials, and infrastructure. The educational reform sought to take over the State management. Its design, with emphasis on teacher evaluation for personnel selection and, above all, permanence in employment was the cause of conflicts that remain unresolved. The reform was applied in a disorganized manner in what should have been a more time-consuming process, especially because of the magnitude of the challenge to evaluate and incorporate almost one and a half million teachers into a new model. Other problems were programming aspects of infrastructure, administrative organization, and paying attention to problems of equity and quality that had a complex regional diversity without adequate organization and conviction of the actors in the educational process.

López Obrador's government has once again addressed the above-mentioned matters. However, it remains to be seen whether he has been able to rescue what works from Peña Nieto's reform and cancel or change what does not work. The debate is heated and still open, and it is yet to be seen whether his government will move towards better and greater learning capacities, technical knowledge, and skills.

A fiscal reform was implemented during the previous president's tenure; the first significant one in many years. It did help to boost non-oil budget revenues through the elimination of certain exemptions and income-tax deductions, to increase the maximum rate of income tax for individuals to 35%, and to introduce a capital gains tax. These are quite noteworthy achievements that managed to cushion the impact of the collapse in oil revenues. However, public debt soared and, inexplicably, public investment massively declined during these six years. Fiscal space was curtailed. In fact, given the inertial commitments of current expenditure, pensions, and debt service, the "policy space" for discretionary fiscal purposes does not exceed three GDP points. This is an insufficient amount to address the deterioration of infrastructure and begin to meet major social lags in health, education, and social protection.

Prior -and in a certain way parallel- to the fiscal reform of 2013, Peña Nieto implemented an energy sector reform, to liberalize and give much more room to private investment in the oil and energy industries that had, for years, been fully dominated by the two major state owned enterprises (SOE): Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) and the Compañía Federal de Electricidad (CFE). Given Mexico's public finances' crucial dependence on the oil sector, which traditionally provided close to 35% of public revenues, this reform had a key role in the Pacto's agenda. The idea was, on the one hand, that by eliminating virtually all restrictions to private domestic or foreign investment, Mexico's energy sectors would have the necessary financial and technical resources to modernize and strengthen their capacit. Given the tight government budget constraint, it was argued that the private sector's intervention was the only option to carry out a transformation of this kind. On the other hand, the energy reform was accompanied by a change in PEMEX's tax regime to strengthen its finances, human and capital resources. Regarding the electrical sector, the reform set important targets to move forward towards a transition to clean energy. By eliminating regulatory barriers to entry, it created a full private market for energy generation and transmission.

Soon the energy industry was transformed: numerous private companies began to compete with SOEs in all energy and oil related activities from exploration, exploitation, transport, storage, commercialization, etc. Active participation of the private sector was encouraged through auctioning the rights to explore/develop a number of oil fields.

The results of the reforms are somewhat mixed. The fiscal budget drastically reduced its dependence on oil revenues. This was, in part, due to the decline of crude oil prices in the international markets as well as due to the results of the fiscal reform in increasing non-oil tax revenues by more than two percentage points of GDP. However, oil production collapsed as PEMEX's revenues and investment acutely fell in real terms (by 15% and 39%, respectively during these years) and investment by private firms did not gain sufficient momentum. The amount of funds fell well short of the government's expectations. On the other hand, the electrical industry did strengthen its capacity and performance thanks to the reform introducing creative forms of allowing private sector participation. Not surprisingly, Mexico's trade balance in crude oil and oil related products rapidly deteriorated and began to register ever increasing deficit.

One of the Pacto's unquestionable achievements was putting in place a regulatory, legal framework oriented to promote transition to cleaner energy.

Unfortunately, López Obrador was even in his campaign, firmly opposed to the energy reform. After taking office he cancelled (whether permanently or temporarily is unclear) key aspects of the energy reform that allowed more private sector activity in the oil and energy industry. By December 1, 2019, his first year in office, progress in favour of a transition -albeit moderate- to clean energy has been reversed. The new government has fiercely pushed for: i) the construction of a new oil reinery (in Dos Bocas), ii) the use of coal for electric generation, and iii) a move against the green initiative for a more liberal use of clean air certiicates.

Inspite of Lopez Obrador's opposition, there is consensus that an in-depth fiscal reform will have to be soon implemented. It should encompass income, expenditures, financing, and other key aspects in its institutional framework. Clearly, there is scope for raising taxes; the 17.2% as a share of GDP in 2017 represents half of the OECD average revenue coefficient and is more than 10 points below that of Argentina and Brazil (Márquez-Ayala, 2018). There are also many other areas where revenues can be raised: collecting property and inheritance taxes, modifying the VAT rate (perhaps generalizing it and removing exceptions), changing tax rates so they have a progressive impact on income distribution.

The Fiscal Budget and Responsibility Law in place more than a decade ago, with its inherent procyclical character, should be replaced by a rule based on structural balance throughout the business cycle. Also, there is a systematic and acute gap between the amounts approved for different items in the government budget annually approved by Congress and the amounts that actually exercised each year. Most worrying, is that Congress only is informed of this difference a year and a half later, too late to do anything about it. Such institutional context question the essence of budget planning and control (Nuñez-González, 2017). A most welcome change in this area would be to create a Fiscal Council in Mexico, in line with the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, as a technical arm of the legislature for the validation of the Finance Ministry's projections of GDP, which relate to a public debt path and other key variables that have a major role for budget matters.

The contraction of gross ixed capital formation by the public sector in real terms at an average rate of 5% per year throughout Peña Nieto's presidency (2012-2018) is a scandal that conspicuously undercut the growth potential of the economy. In addition, his administration paid no attention to the major flaws that -as all experts recognise- mark the institutional and regulatory framework of public works in Mexico: their design, approval, execution, and monitoring of public projects. As has been argued (Gala-Pacio, 2018; Moreno-Brid et.al, 2018) the National System of Public Investment (SNIP, the regulatory framework, has major deiciencies that severely distort its capacity to act as a policy tool to select projects that are relevant from a common, good perspective for development. As it stands, it fails to guarantee that project selection is consistent with a national development agenda. It seems to be more of a bureaucratic agency used to stamp projects based more on political than socioeconomic criteria. There is ample room to improve its capacity to monitor and ensure that public infrastructure projects are executed in time, are high quality, and have an accountable eficient and transparent use of financial resources.

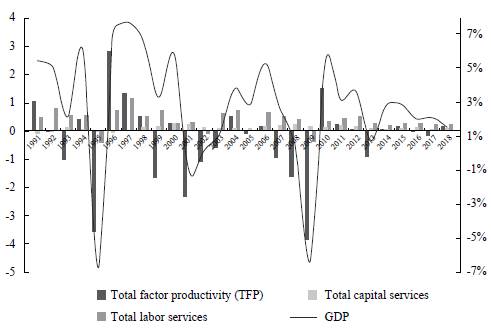

Market reforms failed to induce significant investment to augment and modernize the capital endowment per worker. Without them, any pretence to strengthen labour productivity was illusory (Ros & Ibarra, 2019). The lack of momentum for gross fixed investment (and its virtual stagnation in many industries) made it impossible for capital endowment to signiicantly increase during this period. The persistent lag in labour productivity should not come as a surprise, despite the fact that the NDP placed productivity as the cornerstone of its agenda. As mentioned above, in these years Total Factor Productivity (PTF) actually declined (Moreno-Brid, Dutrenit (coord) 2018).

The evidence points to the fact that, notwithstanding their merit in reorienting output to the external market and in consolidating macroeconomic stabilization, the market reforms (both in their recent version 2012-18 and in previous ones), failed in their quest for high, sustained and inclusive economic growth. They did not succeed in 1994-2008 when world trade and Mexican exports were growing rapidly. Nor have they been able to do so since 2008-09 when, due to the international inancial crisis, the world economy entered into the so-called New Normality, marked by the loss of momentum in international trade. The protectionist tendencies of Trump's government have shrunk even further the odds in favour of Mexico's export-led growth.

Source: Elaborated based on data from INEGI (2019b), Total Factor Productivity (2013=100)

Figure 3 Mexico. GDP Growth Accounting: 1991-2018 (Percentages and Production Value Growth Rate Referenced on the Right Axis)

CONCLUSIONS: GENERAL BALANCE OF THE MARKET REFORMS AND PROPOSAL FOR EQUALITY AND SUSTAINED GROWTH

In December 2018, a new government took office in Mexico, with López Obrador as President. It is too soon to assess whether his agenda will be successful or not. In any case, without cancelling the outward orientation, the export capacity of the Mexican economy, it must place the internal market as an important and complementary engine to boost economic activity and employment.

It is not a question of abandoning the effort to export more and with greater added value, or to reverse the opening up of the country's domestic markets to foreign competition. In order to strengthen the domestic market, the policy agenda must place the reduction of inequality as a priority. This concern was never on the policy radar of the Peña Nieto administration or any of the other presidents over the last three or four decades. As ECLAC stated, the Mexican economy must "grow to equalize, and equalize to grow" (CEPAL, 2010, p.13). The World Bank and the IMF agree that inequality has become a crucial obstacle to economic growth; the institutions provide empirical evidence of international experiences that have succeeded in reducing inequality and promoting growth without jeopardizing macro stability (World Bank, 2016). The OECD and ECLAC have pointed to inequality as major obstacle for Mexico to achieve a higher long-term rate of economic expansion (OECD, 2017; CEPAL, 2010).

The close link between equality and growth was ignored by the structural reforms between 2012-18. This omission, together with the subsequent neglect of the internal market in the Pact's approach, marked the labour reform. In fact, the 2012 labour reform sought greater flexibility in the labour market, without taking into account elements relating to security, quality of employment, and the unbalanced weight between labour and capital in the struggle for the factorial distribution of income. With work being the main source of income, deteriorating conditions undermined the possibilities of reducing inequality and increasing social mobility (El Colegio de México, 2018). This helps explain that during the six-year period unemployment and informality rates fell, but quality work became scarcer, and wages deteriorated, even more among formal than informal workers. Thus, the structural reforms did not reverse the downward trend in the purchasing power of labour income, which had been the case since 2009, in the three occupational categories. From 2010 to 2017, on average and in real terms, the income of employers diminished by 26%, subordinates by 18%, and self-employed by 7%.

Given the evidence, we insist that a new development agenda that changes the dynamics of aggregate demand and, in turn, recomposes supply is required. Policies must be implemented to reduce income concentration and promote social mobility, with full respect for macroeconomic stability and social peace. Fiscal, financial, and monetary policy priorities will have to be reordered to pay more attention to their impacts on inequalities and socio-economic mobility. At the same time, we will have to review social programmes, removing redundancies and inefficiencies in order, hopefully, to move towards a universal social protection system. So far the López Obrador agenda has not centred on these concerns. It has put in place a drastically austere fiscal policy that is extremely procyclical, and the priority is to have a balanced budget and not to incur in additional debt. The president's macroeconomic policies are essentially the same as those of Peña Nieto's in his last years: austerity as a guideline on fiscal matters, and inflation targeting in the context of a floating exchange rate as the core of monetary policy. Trade policy has, at its centre, the ratification of the USMCA agreement that substitutes NAFTA as a regional agreement on managed trade. Industrial policy is, for practical purposes, non-existent, as it takes the back seat to commercial policy. And social policy is now centred on unconditional cash transfers.

Labour policy is the one area in which the López Obrador administration has made major changes. It has approved and put in place a reform along the lines of the reform path announced in 2017 (within the context of Mexico's interest to join the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP)) to modernize key regulations and strengthen trade unions. In particular, it put the minimum wage on a path of sustainable and meaningful recovery towards the levels of dignity that were established as a citizen's right in the 1917 Constitution.

There is an urgent call today for a national agreement to promote fixed investment (public and private) together with an active industrial development policy. Its objectives should be to expand and modernize infrastructure, machinery, and equipment, and to densify the national productive fabric, in order to base competitiveness on innovation and the generation of value added instead of low wages. Such a policy must not neglect the qualitative improvement and diversification of the exportable supply, as well as its capacity to move the rest of the national economy forward. To achieve this, the indispensable instruments required are the strengthening of development banking and the avoidance of a real exchange rate appreciation in the long-term.

As we have previously stated, "in a context of low fiscal revenues, a public policy dilemma arises maintain a small state in terms of public spending, with very limited social rights, or seek sources of income that allow the expansion of those rights. Both options imply fiscal discipline". (Moreno-Brid, Pérez-Benitez, & Villarreal-Paez, 2017, p. 69). The first option is ethically and politically unviable given the long-standing conditions of poverty, inequality, poor economic growth, and low social mobility. Therefore, the second option is the route to follow.

The viability of the development agenda we propose (which differs from the diagnosis and implementation of the 2012-18 structural reforms, and is also not the same as what López Obrador has so far implemented) depends critically on the country's political will to put in place an indepth fiscal reform. Sooner rather than later, long-term budget planning -far beyond the six-year presidential terms will have to be based on an intergenerational social and economic needs perspective. From there, it should proceed to identify the resources needed to fund such initiatives -either through tax or debt- in such a way as to guarantee a pattern of sustainable public sector indebtedness. All of this should include a pressing need for efficiency, transparency, and relevance for the well-being of the population.

In terms of emergencies and their possible consequences on taxation, a major issue is people's security and safety and how to repair the enormous damage that has been caused by internal violence over the last twelve years. Pacifying the country is a prerequisite for long-term productive investment and, more importantly for persistent social peace. However, such pacification has an unavoidable financial cost that will have to be covered by a fiscal reform associated with a fundamental long-term need to create a welfare state that has been perennially absent in this country. One way to do this, as López Obrador has stated, is to reallocate available resources, end corruption, cut duplicate or inefficient programmes, and seek greater efficiency and cost improvements. All these are welcome, but this is not enough to provide fiscal revenues for an amount of, at least, six additional GDP percentage points that are required to adequately address the needs and lags in both social and infrastructure for economic development. Thus, a fiscal reform is unavoidable.

We close with the following assertion: There is no way for the López Obrador government... to avoid fiscal reform. (CIEP, 2017). Will the political capital of Lopez Obrador's government be sufficient to underpin such a fiscal reform and to make a New Social Pact with the private sector to, on the one hand, energize fixed capital formation and, on the other hand, make significant and timely progress in reducing inequality? These are key questions the answers to which will mark the path of development and perhaps the political and social stability of Mexico in the future.