INTRODUCTION

In the last two years Ecuador's economic policy has been characterized by erratic management, resulting in an economic slowdown and even a change in the population's initial positive economic expectations of the Moreno government (King & Samaniego, 2019). In fact, the government, accompanied by a good part of the mass media using politically aligned economic analysts as cheerleaders, has created an environment similar to that described by Klein (2008), in which the population is convinced that there is no alternative other than to accept the contraction of public spending as a solution to a 'crisis' and to ask multilateral organizations for help with economic management.

This is precisely what the Ecuadorian government did at the beginning of 2019 when it delegated the solution of the Ecuadorian economy's problems to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). However, the government's principal objective -attacking the fiscal deficit- was based on a dubious diagnosis that did not account for the economy's structural problems, especially the external sector deficit.

By focusing exclusively on the fiscal aspect, not only was a comprehensive macroeconomic overview neglected, but a message was sent to the public that fiscal policy was responsible for all the economy's ills, including the need to promote austerity, concessions, monetization or privatization of public assets, and a possible reduction in the provision of public services (Vasquéz & Silva, 2019).

There have been several contradictions in economic management: for instance, the approval of a Law of Productive Promotion (LPP) in 2018 that both increased tax incentives for companies and provided a tax amnesty, at the very time the government was emphasising the need for increased budget revenues.

This article analyses the nineteenth agreement signed between Ecuador and the IMF. The objective is to provide an understanding of the implications the proposed economic reforms will have for a fully and officially dollarized economy such as the Ecuadorian one. The hypothesis is that if the agreement is implemented, the economy will be hit by a major recession that is coupled with a major setback for any plans to transform the productive structure.

The article is arranged into six sections. In the first, we introduce the issue; in the second, we present the state of art of the structural programmes and describe the methodology; in the third, we analyse the scope of the agreement and discuss the origins of the agreement and its justifications; in the fourth we reveal and explain, by sector, the commitments assumed in the arrangement; in the fifth, we examine the implications for the planning and financing of structural change; and in the sixth, we offer our conclusions.

STATE OF ART AND METHODOLOGY

Structural adjustment policies imply austerity, privatization, and financial and trade liberalization, and they had been examined in many scopes. One of the main effects had been to "shrink policy space", which reduces public policies' possibility for development (Chang, 2006; Griffiths & Todoulos, 2014; Kentikelenis, Stubbs, & King, 2016; Stiglitz, 2017), the recovery of growth (Weisbrot, Ray, Johnston, & Cordero, 2009), and consumption and poverty (Ugarteche, 2016).

Another point is that there is no policy flexibility, and governments use the IMF conditionally to disguise proposals, which can coincide with pressure groups' interests because they would otherwise not have been put into practice by the opposition (Kentikelenis et al., 2016).

It is often assumed that agreements with the IMF are well designed and the Greek structural adjustment programme is the worst example of design as well as political and economic mismanagement both in Greece and at the European level (Moschella, 2016). These agreements include conditionalities to ensure states' servicing debt, "as well as setting the economic climate for growth ... [but] adjustment comes at a high social cost" (Thomson, Kentikelenis, & Stubbs, 2017, p. 2) because it limits resources for education, health, and social protection (Ortiz, Chai, & Cummins, 2011).

On the other hand, one of the arguments in favour of signing agreements with the IMF is that they act as a catalyst for other aid because they convey good signals. Stubbs, Kentikelenis, and King (2016) found that IMF aid varies in relation to the kind of aid and is stronger in "debt-related relief and general budget support.. .and non-existent for health and education" (2016, p. 513).

In terms of its effects on social variables, Thomson et al. (2017) have compiled the empirical literature since 2000 regarding the aggregate effect of structural adjustment programmes administered by the IMF and other multilateral institutions on maternal and child health outcome variables. They found "unanimous. detrimental association between structural adjustment and child and maternal health outcomes" (2017, p. 9).

The government's alignment in foreign policy, which has led to the signing of an agreement with the IMF, usually means less strict conditionality. This is reflected in non-improving financing conditions (Chapman, Fang, Li, & Stone, 2017). Similarly, Dreher, Sturm, and Vreeland (2013) consider that politically important countries are more softly treated by the IMF. In fact, Chapman et al. (2017, p. 348) said that "when the informal influence is at its peak, (...) the announcement of a new IMF program leads to capital flight". We must remember that the United States has a veto right (Kruger, Lavigne, & McKay, 2016) and the U.S. together with the European countries' (that use the Euro) voting powers "exceeds the corresponding voting shares" (Brandner, Grech, & Paterson, 2009, p. 24).

The methodology we use in this paper is explanatory. As observed in the state of the art, there are no structural adjustment policy studies for a fully dollarized economy. Therefore, this article is based on the context in which the agreement was made. It is explanatory in terms of the content of the agreement in how it reveals these policies influence on structural changes.

In addition, this article uses a mixed approach through the collection and analysis of the agreement's qualitative information as well as interviews and editorials to examine its origins in foreign policy and justification discourses. In the quantitative section, it uses macroeconomic information mainly from the Central Bank of Ecuador, as well as the tables presented in the agreement, to infer the effects of structural adjustment policies in the monetary, financial, external, fiscal, labour, and real sectors.

SCOPE OF THE AGREEMENT, DISCUSSION OF THE ORIGINS, AND PRINCIPAL JUSTIFICATIONS

Beginning in 2015, a number of analysts and media outlets began to promote the idea of the urgent and indispensable need for an agreement with the IMF;1 the government of the time also opened the door when it allowed the IMF to evaluate the economy (IMF, 2015). At the time, it was stated categorically that this was the way public sector indebtedness could be improved, and that accepting the Fund's conditions was essential due to economic policy mistakes made during the past ten years.

After four years of negotiating and a change of government, we returned to the style of economic policy dominant during the so-called lost decade, 19902000, when the country faced the most important crisis of the twentieth century (Martinez, 2006). The government talked about and promoted the benefits of returning to an orthodox economic policy, one based on the benefits provided by the backing of the multilateral organizations, until quite recently.

Scope of the Agreement

Given the discourse, it might have been imagined that the country would receive an amount of resources at least proportional to those initially requested by Argentina.

Table 1 displays a comparison of the two agreements, the Argentinian Stand By and the Ecuadorian Extended Fund Facility Arrangement or Extended Fund Arrangement (EFA).

Table 1 Scope of the Argentinian and Ecuadorian Agreements (in billions of U.S. dollars, as a Percentage of GDP and a Percentage of the IMF Quota)

| Argentina | Ecuador | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of agreement with IMF | 57 | 4.2 |

| GDP for year of Agreement | 518.1 | 106.3 |

| Percentage of GDP | 11 | 4 |

| Percentage of the quota with the IMF | 1,277 | 435 |

Elaboration: Authors.

Source: Dujovne and Sandleris (2018), IMF (2019b), Martínez and Artola (2019).

In fact, Ecuador received a little more than a third of the Argentinian loan. If it had obtained a similar percentage of its IMF quota, the EFA would have provided USD 11 billion. However, to justify the smaller amount, the EFA was disseminated together with the loan quotas from other multilaterals (Table 2).

Table 2 Financial Scope of the Agreement (in millions of U.S. dollars)

| Multilateral Organization | Amount | Increase in amount |

|---|---|---|

| International Monetary Fund | 4,209 | 3,845 |

| World Bank | 1,744 | 1,190 |

| Interamerican Development Bank - IDB | 1,717 | 601 |

| CAF - Latin American Development Bank | 1,800 | 450 |

| European Investment Bank | 379 | - |

| Latin American Reserve Fund | 280 | - |

| French Development Agency | 150 | - |

| Total | 10,279 | 6,086 |

Elaboration: Authors.

Source: Finanzas and Gobierno, 2019 (p. 12).

It is worth noting that the real increase in the quota of the other multilaterals is USD 2,241 million, as the remaining amount is simply the renewal of existing credits, except the USD 364 million IMF emergency loan made after the 2016 earthquake (Grigoli & IMF, 2016).

It is also important to take into account that the funds provided by the EFA (USD 4,209 million) will be received over three years, and are equivalent to 1.35% of the country's estimated GDP for 2019.

One of the present regime's major criticisms of its predecessor was related to the methodology, consolidated or aggregated, used to calculate the debt. During the last few years of its mandate, the previous Government used the consolidated methodology in order to avoid falling foul of legal provisions requiring public debt to not exceed 40% of the GDP. The current government, however, has repeatedly claimed that Ecuador maintained a level of indebtedness close to 60% of GDP although this was based on an aggregated analysis.

In April 2019, the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) presented their new debt calculation methodology, which was similar to the aggregated one; however, the IMF Agreement uses the consolidated methodology despite the fact that the Seventeenth Transitional Provision of the LPP established that the public debt limit of 40% of GDP does not apply for the 2018-2021 period.

The IMF's use of a consolidated methodology can be read as accommodating the government's political weakness, given that, according to IMF projections (2019a, p. 7), the limit of 40% of GDP could only be possibly reached in "2023". If the aggregate debt definition were used, the percentages would be higher and the timeline longer. This confusion in the presentation of borrowing limits and financing needs is a disguised form of accepting the use of the consolidated methodology and concealing the inability to reach the goals set by the MEF as part of the LPP.

Beyond just presenting the debt data, it is also possible to compare how much the amounts received under the EFA represent with respect to the policy measures undertaken before the EFA was signed (Table 3).

Table 3 Agreement Compared to the Policy Measures Implemented in 2019 (in millions of USD and percentage of GDP)

| Millions of USD | % of GDP | |

|---|---|---|

| Financing Needs for 2018 | 8,889 | |

| Amount of Agreement for one year | 1,403 | 1.30% |

| Total losses due to Law of Productive Promotion (LPP): | -1.20% | |

| - Tax amnesty LPP 2018 | -1.00% | |

| - Tax incentives LPP 2018 | -0.20% | |

| Difference | 0.10% |

Elaboration: Authors.

Source: IMF, 2019b (p. 16, 38).

Table 3 shows that the LPP has negative implications for the 2019 fiscal year (1.2% of GDP). In other words, the money provided in one year by the EFA merely compensates for the allowances the government had provided in the previous year. For 2017, the last year on record, tax expenditures represented 4.7% of GDP (Chiliquinga & Ocampo, 2018).

With the new incentives, tax expenditures on incentives are now equivalent to 2.9% of GDP, to which should be added the reduction of 3 points in corporate income tax established by the Production Code of 2010. This reduced the rate to 22%, with a consequent impact on tax revenues of USD 300 million per year.

When comparing what has been received from the IMF against the impact of the latest approved tax measures, we can see that the agreement represents 0.1% of GDP compared to what was lost by the LPP. However, due to political considerations, the agreement had to be marketed positively. The IMF contribution was presented together with USD 2,241 million quota increases from three multilat eral organizations, and the credits these organizations had already provided to the country were omitted.

Origins of the Agreement

Interestingly, the negotiations that led to the agreement with the IMF coincided with a drastic change in Ecuadorian foreign policy.

To demonstrate that Ecuador was relocating its international relations policy within the "acceptable" Western Hemisphere field, at the same time as reaching out to the IMF, the Ecuadorian Foreign Ministry aligned itself with the interests of the United States. The Ecuadorian ambassador to Washington, Francisco Carrion, admitted that "We are well aware of the influence of the United States within multilateral organizations, and that has benefited our country" (Vaca, 2019).

The national government began by requesting assistance from the U.S. in anti-narcotics operations, and consequently granted permission for "observation" flights over our national territory by U.S. armed forces. Julian Assange's political asylum was then withdrawn. The operation of U.S. ships in national waters was authorized on the grounds of combating drug trafficking. The non-intervention in the internal affairs of other nations policy (a basic principle maintained for decades by Ecuadorian diplomacy) was abandoned, with consequent pronouncements on Venezuela. Ecuador moved closer towards relations with the Lima Group, while the dissolution of UNASUR was also proposed.

There is a major concurrence between the changes in foreign policy and the EFA. It can be assumed that the Government ceded to U.S. demands as part of a different foreign policy from the previous government's one, the purpose of which was to obtain the support needed. In the words of the aforementioned Ambassador Carrion, "countries function according to their interests" (Vaca, 2019), which have a quid pro quo logic.

The withdrawal of Julian Assange's political asylum, who was lodged at the Ecuadorian embassy in London, was unprecedented in International Law. The arguments used to justify it were shameful, appealing to base instincts or false alarms about the presence of Russian hackers in the country. This could only be understood as a way of obtaining support from the United States in relation to the EFA.

Assange is undoubtedly controversial, but no less controversial is the way Ecuador allowed the British police to enter its embassy, or the consequent actions of the Foreign Ministry in delivering Assange's belongings to the country requesting his extradition.2 Carrion acknowledges that "there was informal interest on the part of some United States authorities" (Vaca, 2019).

However, the EFA negotiation does not end there. The U.S is now authorised to use Baltra airport on the Galapagos Islands, which hosts refuelling facilities for the US fleet: an unthinkable act, even as part of the most submissive of bilateral relationships.

To conclude with regards to the support received, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence visited Ecuador in July of 2019, offering 'major' support for migration issues. This amounted to USD 35 million. For years Ecuador had assumed major responsibility for the displacement resulting from the armed conflict in Colombia, which had globally totalled seven million people by 2016 (Unhcr, 2018). It is worth noting that Plan Colombia was signed at the end of 1999, and, as a result, the neighbouring country received U.S. aid of approximately USD 5,000 million over five years (Veillette, 2005).

The Moreno government also withdrew from spheres of regional integration that had previously been promoted by Alianza País. The most controversial, even for Bello (2019), was the announcement that the country would leave Unasur, the headquarters of which were located in Quito, and is now in talks regarding the country's incorporation into the Pacific Alliance.

All this generated euphoria on the part of economists linked to influential groups and international organizations. However, after subtracting what was lost due to the LPP, the "support of the international community" (Finanzas & Gobierno, 2019) from the IMF amounted to only one tenth of one point of GDP, or 15.8% of the financing needs in 2018. This was much less than the tax incentives Ecuador provided, which represent fiscal sacrifices. In other words, we are content to receive nothing after handing over everything.

Debt, Country, and Risk as Justifications for the Agreement

After the electoral campaign and the assumption of control by the new government, the major issue of debate was the recurring public deficit that had assumed particular importance in the last three years of the Correa regime.

A discourse was constructed, and widely disseminated by the official and private media, regarding the unworkable nature of the public sector. Its role in the economy was seriously questioned.

One of the central elements in the construction of the discourse was the amount of public sector debt. According to those narrators, it had exceeded the legal limit of 40% of GDP that was stipulated in the Public Planning and Finance Code. The result was not only a legal problem, but also represented possible problems relating to fiscal sustainability.

At a press conference on March 14, 2018, the acting State Comptroller General, referred to a report written by the institution over which he presided, that indicated that the ratio of debt to GDP had reached 52.54% between 2012 and May 2017, thus exceeding the limit of legal indebtedness (Comptroller General, 2018). A few months later, the current Minister of Economy, Richard Martinez, was even more pessimistic when he stated that the amount was USD 58,980 million, or 57% of GDP, adding that: "Citizens need to know how their resources are being managed" (Reuters, 2018).

The surprise came a few months later when the agreement with the IMF was announced. Without so much as a blush, the national government and its control agencies accepted the multilateral agency's version, which showed a public debt to GDP ratio of 44.6% (IMF, 2019b). This was close to 13 percentage points less than what was publicly stated by the Minister of the Economy, who was signatory to the agreement. That value also included debt assumed during the Moreno government, which, between May and December, increased debt stock by 2.4% of GDP (BCE, 2019c).

One could be excused for asking who was exaggerating or who was underestimating the amount of debt, and for what reason? Whatever the answer, the way these events unfolded exposes the use of measurable issues for constructing political discourse. If the principle of transparency that Minister Martinez apparently defends is not evident in this case, what credibility can the word of government spokespeople have with regard to other aspects of the economy, such as the necessary scope of fiscal adjustment, or the situation of public companies? The same questions are pertinent with respect to the Comptroller General of the State and the economic analysts who joined in the chorus of political pronouncements.

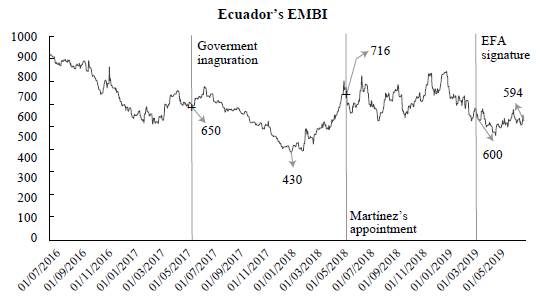

It would be useful to look at the country risk indicator in order to see Ecuador's position in capital markets when it was planning to contract external debt (Graph 1).

Elaboration: Authors. Source: BCE (2019b).

Graph 1 Evolution of the Emerging Market Bond Indicator for Ecuador - EMBI (in points)

The country risk at the time the Moreno government assumed power was approximately 650 basis points, and this subsequently fell to 430 during Carlos de la Torre's tenure as Minister of Economy, although it rebounded when he left on March 6, 2018. Maria Elsa Viteri's time as Minister was very short and led to an increase in the indicator, while during Richard Martinez's time, who announced his desire to sign an agreement with the IMF, there has been no reduction in the external perception of risk.

The signing of the Letter of Intent (LOI) with the IMF led to a fall in the country risk for a very short period, without this translating into improved credit conditions. Based on calls for an agreement with the IMF, it had been assumed that the mere fact of resorting to that institution would mean improving financing conditions (Marchesi, 2003), but so far this has not been the case for Ecuador.

On June 10, 2019, with the signed EFA, the government carried out a 2015-2020 Bond repurchasing operation. The reduction in the amount of the debt was USD 50.4 million in bonds listed above 100% of their nominal value. This amount is minimal compared to what is being paid in excess for the bonds at 10.75% coupon rate, issued in January 2019: at least USD 9 million, or USD 90 million over ten years. They have postponed the rest of the capital payment to 2029, i.e. USD 1,125 million, while in the following year USD 324.6 million will have to be spent on capital that was not repurchased.

If the country risk decreases, the interest on debt is also supposed to fall, but this did not happen. The average rate of the 2020 bonds was 9.5%. It is now 9.85% with a lower country risk, and the debt service will now last until 2029 (King, 2019).

It was a deceptive, unsuccessful, and finally detrimental operation, and although the LOI with the Fund is a type of guarantee for the bond buyers, which according to the government reduces the country risk, this has not translated into an improvement in financial conditions.

In other words, the economy was presented to be the core of the problem, and it became part of a submissive discourse that served the political needs of the government in the internal sphere. This is not exactly rare in current times and in international politics.

SECTORIAL ANALYSIS OF THE COMMITMENTS OF THE EFA

The following subsection presents an analysis of Ecuador's commitments in four sectors that are part of the EFA (monetary-financial-banking, external, fiscal-taxation and real-labour) in order to evaluate the direction of the policies established and their possible effects.

Monetary - Financial - Banking

The fundamental requirement introduced by the EFA in this sector is the independence of the Central Bank of Ecuador (CBE), something initially envisaged for the end of May 2019.

Yet modifying the independence of the Central Bank makes little sense in a fully dollarized economic system, given that the country does not issue money. The Central Bank only circulates a limited amount of tokens, which are fractions of a dollar placed in the hands of the public to prevent prices from having a dollar as the minimum reference. The other important functions of the CBE include acting as a repository for public sector funds and national reserves or bank reserves. And although almost 20 years have passed since dollarization, the CBE also has assets of various kinds -financial and non-financial- resulting from the 1999 banking crisis.

The independence of the ECB, a topic widely discussed during the 1990s (see for example, Alesina & Summers, 1993), is part of the neoclassical logic that assumes that in order to contain inflation, stabilize prices and promote growth, the CBE must decide on monetary policy independently of the government. The objective of this approach is to ensure that the executive exerts no influence over monetary, financial, and credit policy.

An analysis of the EFA shows that with an independent CBE a new State-Banking sector relationship will be constructed, which appears to be characterized by having the State watch over the private banking system based on the argument of possible systemic risk. The financial system is unstable by nature, so granting independence to the CBE would not change this, but it could open the doors for banks, especially the largest, to regulate themselves, which was what happened in the United States in 2008 (Hudson, 2018) or during the 1999 crisis in Ecuador (Salgado, 2000).

In addition to this obligation, the EFA stipulated the following requirements. Their objective was to consolidate the position of the private banks in the financial market:

Eliminate the possibility that a portion of the liquidity be injected into the economy through public banks and the National Corporation of Popular and Solidarity Finances (CONAFIPS). CONAFIPS operates as a second-floor public bank, whose clients are credit unions, mutual funds, savings, and community banks. In this way, financing alternatives are limited by excluding public banks and cooperatives (except for exporters) from receiving excess liquidity resources.

Eliminate the ceiling on interest rates. This will make it likely that these will increase; thus, the cost of investment and consumption projects will also increase, and, in turn, increase the probability of a deeper and longer recession, especially considering the multiplier effects of investment.

Eliminate the domestic liquidity coefficient (DLC) that establishes 60% of the banks' liquidity must be lodged within the country (Resolution 028-2012); this will facilitate capital flight and weaken the domestic monetary system. Ocampo (2015) considers that an administrative regulation is preferable to price regulation. In the LOI, currency exit tax is reduced and the domestic liquidity coefficient (administrative regulation) is eliminated.

With regards to financial resilience, reference is made to capital requirements and other regulations from Basel 3; these could potentially affect credit unions by allowing private banks to expand their market share and, in the worst-case scenario, to even absorb credit unions.

In addition to the above, the major economic policy change that could result from the creation of an independent Central Bank is the accumulation of international reserves, as foreseen by the EFA. The importance of this lies in the effects the measure would have on a fully dollarized economy.

Although there is no consensus (De la Torre, 2019 and Villalba, 2019 have an opposite view), we argue that in a dollarized economy it is not necessary for the Central Bank to hold international reserves in order to guarantee the exchange of goods and services with other countries. While people, businesses, government, and financial system entities use the U.S. dollar as a currency, international reserves are superfluous as they exist primarily to convert national currency into foreign currency.

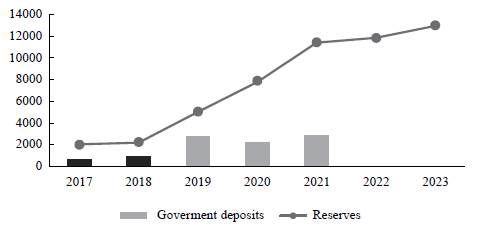

Elaboration: Authors. Source: IMF, 2019b (p. 13).

Graph 2 International Reserves and Government Deposits, Present and Projected (millions of USD)

However, in the EFA agreement, Ecuador has committed itself to substantially increasing international reserves, and the CBE will be the custodian. As is well known, international reserves or freely available international reserves, as they are commonly known in Ecuador, are made up of public sector deposits and bank reserves.

The IMF demands that these international reserves either more than double between 2018 and 2019 or maintain a significant rate of accumulation until reaching approximately USD 12,000 million. This resource accumulation plan has profound implications for fiscal and monetary policy, and contradicts the need for less external indebtedness.

First, and as previously mentioned, there are two major sources available to achieve this accumulation of resources: non-financial public sector deposits and bank reserves or reserve requirements. The EFA (IMF, 2019b) establishes that most of the variation or growth in international reserves will come from the accumulation of resources by the central government: USD 7,647 million between 2019 and 2021. This implies creating collateral for the debt programmed with multilateral organizations that is equivalent to 74.4% of the loans provided. The ability to finance the estimated budget is, therefore, severely limited and therein lays the need to spend, sell state businesses, and contract more debt. In other words, Ecuador is facing a perverse plan focused on weakening the public sector by granting independence to the CBE and giving it the capacity to sterilize a large amount of resources. Second, the agreement will also have repercussions on the money supply. As we know, in a fully dollarized economy such as that of Ecuador, the money supply is largely endogenous, depending on the outcome of all external operations. It follows that the main exogenous element available to increase the amount of money is repatriation of capital or government and private sector external borrowing. If the role of the CBE within the EFA is to sterilize a significant amount of public sector resources, it can be concluded that the IMF has found a way to create a typical structural adjustment programme by contracting the money supply through the retention of public sector funds. Comparing the sum of on demand and quasi-money deposits as of June 2019 (BCE, 2019a),3 the accumulation of funds in international reserves for that year is equivalent to 7.1%.

Why diminish the money supply in this way? In light of what has been said, and given that the country does not have an inflation problem associated with public spending, the most plausible answer is to suffocate the public sector and ensure the destruction of the type of society that was promoted in the 2008 Constitution. Moreover, in the last few years, the presence of significant fiscal deficits accompanied by a reduction in inflation have been observed. We can then return to one of this research's conclusions: that the IMF and governmental economic authorities' diagnoses are biased and have a mediocre understanding of the macroeconomic functioning of a fully dollarized economy.

It is also possible, however, that the accumulation of reserves is intended to mitigate the effects of a possible banking crisis, given that the recession induced by the EFA will be difficult for some financial institutions.4 If this is true, the State-Banking relationship indicated at the beginning of this section could be more fully understood.

There is no doubt that a collateral effect of the policy will lead to a significant reduction in imports and a fall in the trade deficit. A surplus could, therefore, be achieved in the external sector, which is something that would expand the money supply, but at the cost of a tremendous recession.

External

In this section, the aim is to gradually eliminate the currency exit tax (CET) that is applied on currency that leaves the country and currency from exports that are not repatriated (Echeverria Villafuerte, 2018). According to the LPP, this tax does not apply to new investments, which could encourage the return of some capital flight, and would be a gift for those who do not comply with fiscal obligations by keeping resources abroad.

With this measure, it is quite likely that capital flight, a chronic problem in Ecuador, will be further encouraged. Together with the accumulation of international reserves, this could lead to a monetary contraction so severe that the recession and consequent destruction of employment and the fabric of business would entail a serious setback for the country.

Financial Action Task Force (FATF) rules, such as anti-corruption legislation, are to be promoted at the end of September 2019. However, in relation to the country's needs, the legislation largely amounts to saluting the flag, as it does not deal with tax evasion and avoidance through commercial operations: one of the economy's fundamental problems. Within the country, 70% of imports have unit prices of less than one dollar, which provides strong indications of a weak customs system: one that encourages undervaluation as a way of paying less tax. Importers want no safeguards at all, and to be able to bring in whatever they like. Abusive transfer pricing is also used in exports and for currencies that are not repatriated. Hong, Cabrini, and Simon (2014) find that the undervaluation of Ecuadorian banana exports to the United States over a period of ten years represented 82% of the fiscal deficit accumulated between 2000 and 2009.

The assumptions about the external sector's performance are based on the trajectory of oil exports, as this occupies first place in external sales and, in addition, is an important source of fiscal revenue. Surprisingly, the IMF assumes that in 2019 the average price per barrel will be USD 47.8. This is a reduction of 21% compared to the previous year, and is a price that implies maintaining both the value of exports and the fiscal income when, in fact, a 15% increase in export volumes is expected due to the incorporation of production from the Yasuni protected area.

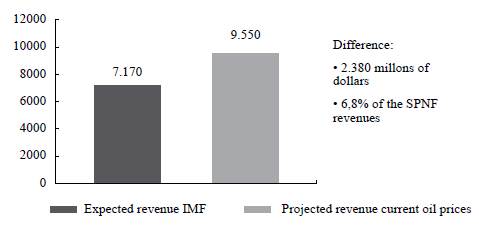

Elaboration: Authors. Source: IMF, 2019c (p. 13).

Graph 3 Oil Revenues of the Non-Financial Public Sector, Expected by the IMF and Projected at Current Prices (in millions of USD)

If this case is analysed using the average price between January and June 2019 of USD 57.05 dollars per barrel, it is likely that the non-financial public sector oil revenues will be 6.8% higher than estimated - some 2,380 million dollars: a figure that almost doubles the annual IMF disbursement. Likewise, the external deficit estimated by the Fund will fall. According to the EFA, oil exports will fall by 8.7%, which is equivalent to 765 million dollars, despite the fact that up to June this year exports have grown by 3.7% due to a 9% increase in the amount of oil sold (BCE, 2019a).

Fiscal - Taxation

The Ecuadorian Constitution guarantees rights, and tax collection must, therefore, finance the provision of social services, regardless of whether we use them or not. The General State Budget has increased in recent years with respect to GDP, as the State now has the obligation to provide health, education, social security, housing and infrastructure to the entire population.5

However, as was previously mentioned, public sector financing became part of an alarmist strategy. When it was incessantly repeated that the fiscal issue was the big problem, what in reality was being questioned was the type of society the Constitution should protect.

The objective is clearly to present austerity and taxation as a strictly "technical" issue. Adjustment was inevitable, something for which there is no alternative, and, as a result, privatizations could be easily sold. However, privatization only finances temporarily the fiscal deficit but does not reduces it and is detrimental to comprehensive coverage of social services, unless the government establishes a regulatory institution that has sufficient power to control the provision and quality of concessioned public services (Kikeri & Nellis, 2004). However, this has not been discussed.

Together with privatizations, a strategy inherited from the previous government that has been extended by the current one, the aim is to generate more income by exploiting natural resources: a sector that is used as an adjustment variable (Samaniego, Vallejo, & Martinez-Alier, 2017) rather than establishing a more equitable and redistributive tax system. The EFA insists on a tax reform (by the end of August 2019) based on indirect rather than direct taxes, explicitly contradicting Article 300 in the Constitution (Asamblea, 2008), which establishes that the tax regime will prioritize direct and progressive taxes. Such a decision will have recessive (Carrillo, 2015) and inflationary effects, and will lead to a poorer distribution of income, explicitly contradicting the supposed benefits of the programme developed in Washington as well as the explicit principles of the "Prosperity Plan" (Finanzas & Gobierno, 2019). This is the misleading name given by the government to the set of policies contained in the EFA.

Despite government and IMF rhetoric, there is another way to finance the budget without these types of damaging and inequitable policies. Using measures including the control of import sub-invoicing, export transfer prices, a progressive income tax, the expansion of tax controls in all orders, and an adequate projection of oil revenues, the financing needed to sustain public spending in accordance with the constitutional principles would be much less, and much more manageable. It would, consequently, be unnecessary to ask an international organization to design a recession using fiscal, monetary, and financial policy.

Real Sector and Labour Market

The labour reforms are part of the neoclassical logic which affirms that in order to increase growth, it is necessary to boost supply through structural "labour market reform" (IMF, 2019b, p. 76). As a result, the authorities have included tax expenditures as tax incentives that do not guarantee the creation of more jobs, and, in terms of growth, have even been questioned by the Fund itself (Orozco, 2019).

Reducing labour rights in the public sector will be achieved by laying off workers and offering new contracts with lower salaries, a process that is already under way. Public officials' salaries are being questioned to match those in the private sector.

This idea is based on a flawed analysis, given that a large number of public sector employees have a higher level of education than workers in the private sector, which would explain the difference in light of the neoclassical theory of human capital (Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2004). In other words, the plan is to compare doctors, nurses, teachers, etc., with workers in the private sector. While in the public sector 73% of employees have university education, the figure is 48% in the private sector according to the Enemdhu in December 2018 (Inec, 2018).

The labour reform legislation has not yet been tabled and could include an increase in probationary periods as well as the facilitation of dismissal. The reform could also include instruments that would make workers' employment situation more precarious, in contrast to the subsidies or tax benefits that capital receives. The latter could even provide an incentive for companies to declare themselves bankrupt without assuming their worker liabilities, which would then return as new investment, even as 'foreign' investment.

The promotion and consolidation of privatizations will also involve an increase in public service tariffs, a tactic that failed when an attempt was made to increase the public electricity rate and some consumers bills rose. Such increases will clearly affect the household purchasing power and reduce overall demand in the economy, thus further aggravating the recessive cycle.

Finally, it is repeatdly heard in the labour sphere that the social security system is broken, and voices are speaking in favour of instituting individual accounts: something that will only weaken the solidarity of the current distribution system.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE EFA FOR STRUCTURAL CHANGE AND FINANCING IN A FULLY DOLLARIZED ECONOMY

With the adoption of the EFA as the principal economic policy instrument, and in the absence of a programme or strategy to change the productive structure (King & Samaniego, 2019), the other major economic imbalance not dealt with is the external sector trade deficit.

In the 2007-17 presidential period, the various versions of the National Development Plan all had the revitalization of the productive sectors as their principal objective, and moving from an economy based on the extraction of natural resources to one in which goods with high-value-added content were produced as a priority. Despite the limited results, there was an effort to relect on and design policies and to point out the difficulties.

What we wish to highlight in referring to these public policy instruments, is that in the current period of government not only are free trade agreements privileged as the only strategy, but also that planning has been completely abandoned.

What we have witnessed is a regression, a fundamental setback due to the fact that 'macroeconomic stability' is now considered to be equivalent to the control of public spending: i.e. the mechanism necessary for the proper functioning of the other sectors of the economy. Stated another way, as part of the policy of transferring economic planning to the IMF, the notion that the best industrialization policy is the lack of one, has once again become current, which Grabel (2011) has also pointed out.

Consequently, the only concrete action, in terms of production and investment, has been the LPP. Through this legal instrument, exemptions from the original legislation were increased, and, as noted above, tax expense was extended, and interest payments and fines for tax debtors were forgiven. In other words, at a time when the economic authorities were arguing that the main problem for the country's economy was the fiscal deficit, public revenues were actually being reduced.

The other mechanism to promote production is the deterioration of the conditions of employment, the so-called flexibility, which is also indicated in the EFA as being necessary for promoting future growth. With the government's complicity, the EFA has, therefore, obliged the country to adopt the demands of business sectors that have been talking about the need to increase productivity since dollarization was introduced. After almost 20 years, these sectors are once again speaking of labour costs as the main, almost exclusive cause of the competitiveness problems faced by country's exports, and of the increasingly difficult task of competing with imported products in the local market.

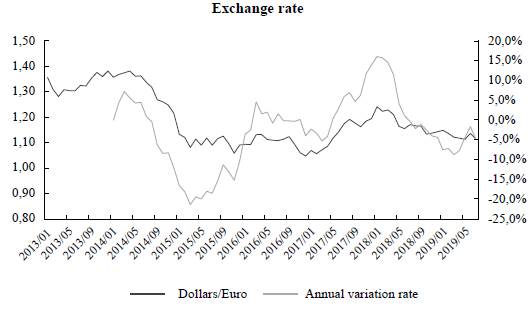

The U.S. dollar has gone through a phase of appreciation since the collapse of primary product prices during the last months of 2014, and there has been a clear phase of depreciation between May 2017 and May 2018. As a consequence, the real Ecuadorian exchange rate suffered the same fate, that is, it gained in value, and exports subsequently became more expensive while imports fell in price. If wages become the adjustment variable for changes in the nominal and/or real exchange rate, as the EFA intends, then the economy is clearly not viable as this implies that domestic consumption will be as volatile as the exchange rate. It is therefore necessary to confront the problem and design a production policy appropriate for dealing with these external shocks, which are compounded by the fact that the country does not have its own currency.

In this context, it is clear that production policy will be exclusively based on the fiscal balance. While the possible signing of more trade agreements could have some impact on foreign direct investment, these would further hinder the competitiveness of domestic production: the entry of cheaper imports in a scenario of domestic demand, compressed by the economic policy contained in the EFA, will make the reactivation of productive activity impossible. The adopted decisions are clearly aligned with the powerful importing sectors' demands that consider these the only way to reactivate the economy.

Elaboration: Authors. Source: BCE, 2019a, Monthly Statistical information.

Graph 4 Evolution of the Price of the U.S. Dollar Against the Euro (in dollars per euro and percentage of variation)

Another implication of the EFA for financing a structural production change strategy is related to the small fiscal space it provides for any future policy of change. The EFA could, therefore, be understood as a way to guarantee both resources for the payment of bondholders and liquid resources in case there are problems in the financial system deriving from the application of the policies set forth in the previous section.

As part of the discussion about which debt methodology to use, and above and beyond the political implications of each one, it is important to note that a consolidated debt definition implies differential treatment of internal debt related to social security (King, 2015). While this could naively be understood as a way to meet the maximum debt ceiling or portray lower amounts of debt, in practice it generates a distortion in savings. If the external debt is guaranteed and the internal debt is not, capital holders will withdraw resources and lend them from abroad, an operation known as 'capital roundtripping' (Beja, 2005). This is even clearer when the debt holders are the banks themselves.

If the LOI with the IMF, the country risk, and what is mentioned above regarding the public sector external debt are taken together, it can be seen that these could provide fertile ground for collusion. On the one hand, a smaller amount of debt is acknowledged, which should have led the markets to provide Ecuador with less punishing credits, and, on the other, the signing of the LOI should have acted in the same way, as it is assumed that the multilateral agency will monitor the payment of new emissions to reduce public sector spending and the accumulation of reserves in the ECB.

The debt re-profiling operation increases the payment of interest over time, and signals a lack of direction in economic policy, clearly benefitting bondholders.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the efforts made by the Ecuadorian government to integrate the country into traditional international financial circuits, it has received very little for its efforts in relative terms, compared, for example, to Argentina. Likewise, despite signing the EFA, the issuing of new bonds has not involved a reduction in interest. This could indicate that the external sector's problems, the country's most problematic economic imbalances, are not considered by the EFA in any way. As a result, neither the country risk nor bond interest has been reduced, as was announced by the IMF's pro bono advocates in Ecuador before the agreement was signed.

It seems that Ecuador has been obliged to align its international policy with the interests of the U.S., and completely abandoning its historical independence in the process. As the Ambassador of Ecuador in the United States has said, the influence that country has on multilateral organizations is extremely important.

If that is serious, more so is the path taken as a result of commitments assumed in the EFA. If stabilization funds were created after the 1999 economic crisis, in reality their purpose was to establish collateral for the payment of the external debt (Suárez, 2003). This time, an effort has been made to confuse public opinion with a project for the independence of the Ecuadorian Central Bank, whose main objective is to establish reserves or maintain a disproportionate amount of deposits in relation to the economy, perhaps with the purpose of anticipating problems in the financial system associated with the economic slowdown and the already-mentioned problems in the external sector. The creation of this new fund to guarantee payment of the external debt will be at the cost of sterilizing the resources provided by the international financial organizations. In addition to the effects such a policy will have on public spending, which will be stifled, there will be a significant monetary contraction, implying an exceedingly stern test for the viability of the dollarization.

Without doubt, another serious effect is the flexibility of the labour market. The precariousness of working conditions will multiply the hours dedicated to unpaid work within the lower middle class and for the most vulnerable and poorest households. This is work carried out mainly by women, as can be concluded from the analysis that feminist economics makes up the care economy (Rodríguez, 2015). In the same vein, while an adjustment to the public sector has been proposed, another major 'adjustment' will be applied to environmental systems, as the extraction of more natural resources in order to export metallic minerals and petroleum is to partially circumvent the appreciation of the exchange rate and the lack of competitiveness of a fully dollarized economy.

The central theme of the EFA appears to be the asphyxiation of government and the possible deterioration of the services provided by both public sector companies and entities. The current government, together with the opposition to the previous administration and the help of almost the entire media, continues to assert, repeatedly, that the only problem with the Ecuadorian economy is excessive public sector expenditure. While there are many alternative ways to reduce this, the most important and fundamental aspect of the present economic plan is that it will lead to a restriction of access to the rights enshrined in the Constitution, which are tightly focused on the notion on a holistic view of human wellbeing (Max-Neef, 1993; Sen, 2000).

The LPP reduces tax burdens at a time of shortages, and, together with other projects designed to reduce labour costs, will leave some businessmen as the reforms' major beneficiaries. What seems to have been forgotten is that what is beneficial for everyone is an internal market with adequate purchasing power and a growing economy, not the macroeconomics of recession that the government and the IMF seem to have in mind.