INTRODUCTION

How is Colombian economic history taught in Economics Departments? Is the teaching of this course impaired by gender bias? Following the definition of Nelson (1995), we define gender bias as differentiating the role, actions, and participation of people as male and female based on gender-based functions and treating them unjustly in distributing burdens and benefits in society. In class and in teaching, we understand gender bias as an unequal or differentiated treatment between men and women in the topics addressed in class, the methodology used, and the readings listed in the syllabus. This unequal treatment privileges the male's perspective of a field -economic history-, it favors the role of men in historical events, it mainly relies on male-authored literature, and hence, it derives into bias in teaching and analyzing history. Moreover, fewer women's works, and books are cited, read, and analysed. Also, fewer discussions referring to women in history are included and pedagogic activities do not encourage a gender perspective which leads to the persistence of a cultural bias towards certain types of socially defined activities for women.

The idea of gender bias in classrooms is not new. The teaching of Economics is not free of gender stereotypes or discrimination. The seminal work of Ferber and Nelson (1993) underscores the discipline as masculine in its assumptions, examples, and the voices used to present its method and hypothesis. Indeed, in their review of introductory economics texts, they find that women and feminist concerns are neglected. Other works, such as Kuiper and Sap (1995), Lawson (2006) and Kuiper (2008), set forth some of the epistemological difficulties that orthodox economics faces when taking gender adequately into account. In particular when it comes to the language of an economic theory that assesses the individual as a man whose behavior is analysed and that assumes a woman is invisible in economic decisions. This view is presented in class and reinforces gender bias in economics. This literature has also set forth different ways in which feminist economics could complement orthodox economics by addressing new questions, using innovative research methods, or even by questioning and changing the ways in which economics is taught. Yet, pedagogy in economics, and in particular ways of including the gender debate in an economists' education are topics that remain marginal in the profession.

This paper aims to respond to the existence of a gender bias participation of women in teaching Colombian Economic History (CEH). We want to understand the potential breach in teaching CEH considering two categories: relevance and participation. These categories allow us to address whether gender bias is explicit and visible in the way the course is taught and in the way research in economic history in presented in the syllabi.

To address the potential existence of gender bias in terms of relevance and participation in CEH, we construct a database of the syllabi of the CEH courses at twelve universities to analyse compulsory and complementary readings, topics, and methodologies. We complement this analysis with interviews of scholars that either teach CEH or carry out research in this field. This analysis is not intended to be a generalization of the presence of gender bias in economic history. Instead, we seek to contribute to the debate on teaching biases based on the case of CEH.

The paper is divided into five parts, including this introduction. In the second part, we present the review of the literature. The third part gives an overview of CEH in undergraduate programs in Colombia. Subsequently, we present our empirical analysis of syllabi and interviews. Finally, we conclude that while female professors include more female-authored readings revealing a gender gap, women's participation is still weak in the readings assigned and in discussions in-class. We conclude that research and the teaching of Colombian Economic History reveal gender biases similar to those present in the economy, as well as a slowness to change these biases despite a growing awareness of gender discrimination among CEH scholars.

LITERATURE REVIEW

There is a growing literature on gender bias, gender stereotypes in science and in teaching focusing on female representation, and on the presence and results of a hidden curriculum. To our concern, there are no works on gender bias and female representation in the field of Economics in Colombia much less in Colombian Economic History.

Gender Stereotypes in Education and Teaching

For Bailey and Graves (2016) androcentric and gender stereotypes are present and reproduced by education and teaching through the notion of a hidden curriculum, everything that is taught in addition to the contents of the course (attitudes, values, among others), loaded with gender stereotypes. For Barrera (2001) and Ramírez et al. (2019), the hidden curriculum affects women's decisions regarding desertion and professional choice orientation, thereby limiting women's inclusion in nontraditional activities or disciplinary areas. Brown (2000) analyses the educational programs of fifty American universities, finding no courses focused on gender matters. Brown (2000) also finds that gender issues do not appear in the curricula and syllabi of specific courses in the fundamentals of education, social studies, English language and arts, or else these issues are mentioned in class for just a few minutes, but never as a central theme. Furthermore, Brown (2000) describes how teachers include gender-fair classroom practices (such as engaging both women and men), as if that would include a gender perspective on the topic taught. O'Reilly and Borman (1986) and Macedo et al. (2015) consider that education still continues to reinforce gender roles and stereotypes such as men are better for math, science and engineering and women do well in language, health care and social studies, even though women have achieved massive access to education.

As Colgan (2017) suggests, readings and instructors in charge of the courses affect the students' perception of the field's top scholars and the principal topics of debate. Recent studies find that female-authored readings are significantly less represented than male-authored readings; suggesting that a lower proportion of women as faculty members is correlated with this outcome. In fact, they observe that women appear to be more reluctant than men with regards to assessing their investigations as compulsory readings which may indicate that even with a lower proportion of women in departments, an additional effort could be made to include more women-authored readings (Colgan, 2017; Diament et al., 2018; Hardt et al., 2019; Phull et al., 2018). The readings for a course are not only a matter of distribution of authors but are referents of a "canon" and a role model as the authors that students must read can significantly impact the diversity (or the lack thereof) of viewpoints represented in these courses.

Gender Stereotypes in History and Economics

In both economics and history as separate disciplines, the debate points to the gender stereotypes that appear in the literature used in courses, in the cases and examples used to illustrate a topic, in the generalization towards a masculine view, and in the bias of the instructors who teach the courses. This debate has not reached economic history as an area, but the joint analysis of both fields might explain how gender bias works.

Analyses of gender stereotypes appear to be more extensive in history compared to economics, possibly because history is a discipline that is taught starting from elementary school and the type of readings and the masculine view of history might illustrate an early gender bias. On the contrary, economics is a professional field that is taught mainly at the undergraduate level and is not part of any potential biases in early education (school). Subirats (1999) and Gómez and Gallego (2016), analyse gender bias in history teaching based on the information found in schoolbooks and on the perception of students regarding the participation of women in history. The authors note male predominance in the images of history textbooks and, therefore, the persistence of gender and androcentric bias. The presence of women in textbooks may influence the understanding of the social and historical roles of men and women, not only in their traditional roles but in the major political and economic decision-making activities (Chiponda & Wassermann, 2011; Gómez et al., 2015; Grant & Sleeter, 1986).

There is a growing awareness to include absent voices, yet the way history is taught has not changed in decades, suggesting the persistence of an androcentric view in class. Despite the consolidation of women's history as a historiographic trend, women's contributions have little influence in the educational field (Dalton & Rotundo, 2000; Riley, 1979; Sánchez & Miralles, 2014).

In economics, the analysis of gender bias includes the role and participation of women in the discipline as well as bias in method, language, and teaching. Concerning the gender gap in the economics field, Perona (2009) and Stevenson and Zlotnik (2018), argue that the discipline is male-dominated. Indeed, men outnumber women at every level of study from undergraduate to PhD and from high school economics teacher to full professor at university. The authors explain this is partly because of the limited role women play as "role models" that encourage girls to study and be part of the field and also the analogy of economics as a difficult discipline traditionally undertaken by men. For Bayer and Rouse (2016), the lack of diversity in economics is due to implicit attitudes and institutional practices that include stereotypes at the moment of choosing one's career, and also in hiring and promotion processes, among others. Paredes et al. (2020) wonder whether an unequal treatment of women in economics arises because of a persistent gender bias in the discipline and in students. Their results suggest that economics students have a sexist bias compared to students of other fields and, in economics, this gender gap becomes more pronounced in upper-class students.

Concerning gender bias in language, method, and teaching, Nelson (1995) and Gustafsson (2000), argue that androcentrism is part of the language and the mainstream economic approach from economic research to the construction and evaluation of economic policies. She points out that while many women have entered the world of economics and have incorporated discussions concerning gender, the economic mainstream is still reluctant to include this approach. Nelson (2016) explains that a gender approach goes far beyond analysing what women economists have contributed to the discipline and has to do with the destruction of gender stereotypes that influence it, in the topics studied, in the methodologies used, and in the relevance given to research and theories. For Frank et al. (1993), economists behave in a self-interested way rather than a cooperative one and the exposition of self-interested models used in economics altered the way economists behave.

As for the teaching gender bias, Stevenson and Zlotnik (2018) show that women are underrepresented in principles of economics textbooks affecting the students' views regarding discrimination and gender diversity. They point out that economic textbooks live in a past time, where women barely appear in examples and the choice of pronouns privileged men.

We propose two categories from the literature review to analyze gender bias in teaching: relevance and participation. The former, relevance refers to whether the gender issues are visible in economic history, either in the syllabi, explicitly, and/or in discussions in-class. We associate relevance with three main elements: the notion of the hidden curriculum (Bailey & Graves, 2016; Barrera, 2001; Ramírez et al., 2019) current stereotypes in the field of economic history (Colgan, 2017; Diament et al., 2018; Hardt et al., 2019; Phull et al., 2018; Stevenson & Zlotnik, 2018); and the self-awareness of women in economic history (Ferber & Nelson, 1993; Gómez et al., 2015; Grant & Sleeter, 1986; Nelson, 1995; 2016). The latter, gender bias in terms of participation refers to the relative weight of women in the field as teachers, in academic production, and as researchers, as a great part of the literature refers to an unbalanced participation in the field, in accord with the contributions of Perona (2008, 2012), Bayer and Rouse (2016), Colgan (2017), Diament et al. (2017), Phull et al. (2018), Stevenson and Zlotnik (2018) and Hardt et al. (2019).

ECONOMIC HISTORY IN COLOMBIA AND ECONOMICS

As in many other countries, students in Colombia choose a college-major and are enrolled in a specific major from the first day they enter college. Students initiate economic studies (mainstream), beginning with the first year and continue for around five years. From the beginning, economic studies include four disciplinary areas: microeconomics, macroeconomics, econometrics and history, as well as economic thought.

In Colombia, there is a strong commitment to the themes imparted in university level economics training. This consensus has been reached mainly because economics is a regulated career that requires a professional ID to validate the diploma in order to work with the state (for private institutions it is not a must).1 Also, the Ministry of Education requires that all students take a professional examination designed by the ICFES2 to certify the abilities and competencies acquired as an economist3. The economics departments reached an accord defining four areas required for graduation in economics: microeconomics, macroeconomics, econometrics, and history as well as economic thought. This agreement led to a minimum of topics for teaching in the history and economic thought area, including CEH. Indeed, CEH has a long presence in economic studies reinforced by the State Examination.4

CEH is a compulsory course in almost all economic degree programmes. It has a different design from other economic studies where "national" economic history and world economic history are elective courses. This fact differentiates economics degrees in Colombia from those of other countries, mainly those with Anglo-Saxon education. As part of the debate in economics regarding the 2008 crisis, a growing literature has debated the relevance of teaching economic history as a response to the failure to "predict" the global financial crisis. Docherty (2014) analyses the relevance of re-introducing economic history which was removed long ago from the curricula. He suggests that by doing so, macroeconomists might provide better responses in times of crisis, not necessarily in predicting them but in having a long-term view of the crises and economic policies. viewing history and financial history as necessary for understanding discontinuities in economic performance and different economic policy regimes and results at other moments.

In Colombia, the debate has pointed out the need for a more in-depth view of economic history. In the last 15 years, many economic degrees have included the traditional course of CEH, as a complementing course on general economic history. Hence, the economic history field has been strengthened as part of the training of future economists. Further, several graduate programs in economics (master's degrees and PhD programs) include economic history as a field to delve deeper into during the studies but only as elective courses.5

In terms of academic production, the tradition of CEH has been long, initiating in the middle of the 20th century with the first books on economic history.6 Since then, an extensive tradition of economic historians has arisen, first from the field of history, switching in the 80s to the economics field, in accord with the international path of economists analyzing historical facts, historical performance, and development view (Meisel, 2007). Male economists have written the bulk of CEH's literature on various topics, including the colonial economy, industrialization, coffee and agriculture, the path of development, the monetary economy, the labour market, land distribution, and fiscal policy, among others. The development of the economic history field in Colombia follows the path of the discipline being predominantly masculine in enrollment, academic positions, and in participation in research groups and with horizontal and vertical segregation7 that represents inequalities and mechanisms of entry into the field and promotion (Daza & Pérez, 2008; Liz, 2012).

Economic history in Colombia is not an autonomous field. Instead, economists with different approaches proceed based on their approaches to the economic history area, according to their interests or research agendas. Few economists call themselves an "economic historian"8 on their CV. Being a versatile field that draws on other economic areas according to the object and temporality of the research, it is expected to include several academic products, mainly when it refers to recent times in economic history.

FROM THE SYLLABUS TO THE DATA

Our findings derive from a two-stage analysis. In the first stage, we construct a dataset containing the readings of twelve Economics Departments ranked among the top 25%9 in the institutions of Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) ranking. This ranking allows us to have some regional variety as it covers five main cities in Colombia: Bogotá (the capital city), Medellín, Cali, Cartagena, and Barran-quilla (Table 1). We analyse the syllabi for two years (2019 and 2020). In the second stage, we implement interviews with scholars, both professors and researchers in CEH to validate our analytical findings from the first stage.

Table 1 Top 25% Universities with Economic Departments According to RePEc*

| University | City |

|---|---|

| Universidad del Norte | Barranquilla |

| Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano | Bogotá |

| Universidad de Los Andes | Bogotá |

| Universidad del Rosario | Bogotá |

| Universidad Externado de Colombia | Bogotá |

| Universidad Nacional de Colombia | Bogotá |

| Pontificia Universidad Javeriana | Bogotá |

| Universidad del Valle | Cali |

| Universidad ICESI | Cali |

| Universidad Tecnológica de Bolívar | Cartagena |

| Universidad de Antioquia | Medellín |

| Universidad EAFIT | Medellín |

*not in any order - grouped by city.

Source: RePEc-Colombia (2020).

We build two databases from the syllabus information. The first database is a general overview of each course. We collected data related to methodology, objectives, compulsory and complementary readings, including the percentage of female authors in the bibliography. The second analyses each reference author and variables such as gender, academic career, places where they studied, among others. We gathered 444 observations, and the methodology used here is in line with the works of Colgan (2017), Diament et al. (2018) and Hardt et al. (2019), who implement a syllabus analysis to address the participation of women in other fields. While we are aware this is an initial outlook of the situation in CEH, it gives an overview of the area of Economic History and the discipline of Economics.

Empirical Analysis

The typical syllabus of CEH covers the long-run economic development of Colombia from the colonial period to the end of the 20th century (roughly from 1550 to 1999). Topics included in all syllabi are fairly homogeneous including Colonial economic institutions, institutional change with the Independence, the agrarian-export growth model, and the main changes and economic cycles of the 20th century. This course is an opportunity to relate economic theories and methods with historical facts. It is one of the few courses that motivate large in class discussions among students.

CEH courses are exceptional within the economics curriculum. Class discussions, group projects, oral presentations, and class participation are part of the courses' final grade. This criterion for grading is infrequent in other compulsory courses such as econometrics, microeconomics, or macroeconomics. These activities allow for developing other essential skills, different from analytical thinking and for fostering critical analysis and argumentation to associate economic theory with its historical development (Rody & Borg, 2001).

In terms of the methodology used in class, we find that all syllabi highlight the need for oral participation and debate in class as part of the final grade. Besides, half of the courses establish a final written assignment with a large spectrum of topics but none explicitly including a female or gender perspective. We also find that 15% of the syllabi have a session dedicated to gender economics, mainly relating to labour discrimination and women's participation in the labour market.10

In terms of gender participation, 50% of CEH instructors are female, presenting equal gender participation as instructors. Regarding women's presence in the syllabi, 91% include female authors or coauthors in their compulsory references. However, female-authored literature is still minimal; on average, only 18.6% of syllabus references are female-authored. The highest participation of female-authored references found in a syllabus is 32%. We are aware that this is associated with female participation in the economic history field. While CEH has been researched and written by men since the mid-20th century, women initiate their inclusion in graduate studies in the late 1930s. In economics, female participation has been low and is in accord with the international trend of about 30% of women that are admitted to economic undergraduate programs. Even though this situation might explain the lower participation of compulsory female readings, it is insufficient to explain why a syllabus does not include women's references or why the average is still low when it might reach 32%. Following the results of Colgan (2017), Diament et al. (2018) and Hardt et al. (2019), we found that female professors tend to include more female authors than male professors do, since they include, on average, 25.9% of female authors, in contrast to men who only include 10.3%, on average.

From this analysis, we can say that CEH is mainly written and researched by men, and this pattern may contribute to reinforcing a "masculine perception" of CEH in terms of believing that predominately men are writers and researchers in the field. From our database of compulsory and complementary11 readings, we tally up 235 unique observations, of which 78.3% are men authored (by a single man or coauthoring with other men). By contrast, only 9.8% are female-authored readings (by a single woman or coauthoring with another woman). The rest, 8.4% are of mixed authorship.

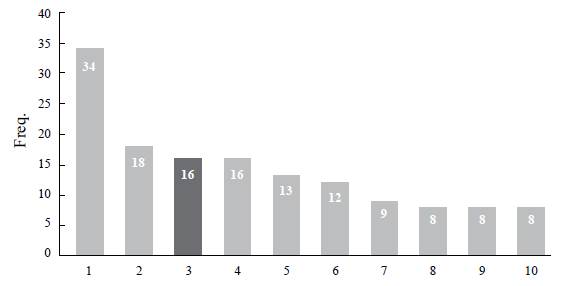

As seen in Figure 1, in the top 10 most widely read authors there is only one woman -Maria Teresa Ramirez-, evidencing the great concentration, not only in the entire syllabi but also that the top authors are mainly men. This reinforces the field's masculine view and can be interpreted in terms of Lawson (2003) and Kuiper (2008), as the implicit perception that predominately men write economic history.

Note: grey color is for men and black color for women. Source: Author's elaboration based on the syllabus.

Figure 1 Top 10 Most Widely Read Authors by Frequency of Readings and by Gender

We divide the syllabi into 22 topics, and organize them into four categories: micro-historical processes, macro-historical processes, historiography and political economy. This distribution's logic addresses the weight of the macro-historical process of the readings as those are less likely to include women and gender concerns in economic history (Libecap, 1997). Macro-historical processes are long-term trends in economic history that aim to determine the roots of change and the developmental path of an economy (Galor, 2011; Supple, 2011). By contrast, micro-historical processes analyse small research units such as communities, settlers, minorities, or groups attempting to respond to economic history concerns but focusing on small places or populations (Burke, 1991). Historiography refers to the literature that addresses the methods and development of the field of economic history and the extension of the body of economic history works. Finally, political economy includes works that address economic theories which explain capitalism and its changes associated with historical factors (Coatsworth, 2005).

In terms of the theoretical approach to CEH, 74.5% of the readings focus on macro-historical processes. By contrast, 23.4% of the references are related to micro-historical processes and, only 1.7% are readings which address gender gaps in economic history, particularly in the labour market, in line with the idea that economic history is about macro rather than micro-historical processes as suggested by Landes (1998), Lie (2007). Historiography accounts for 1.3% of the references, and political economy is marginal with less than 1% (Table 2).

Table 2 Readings According to the Categories of Economic History

| Economic history approach | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Macro processes | 175 | 74.5% |

| Micro processes | 55 | 23.4% |

| Historiography | 3 | 1.3% |

| Political Economy | 2 | 0.9% |

| Total | 235 | 100.0% |

Source: Author's own elaboration based on the syllabi.

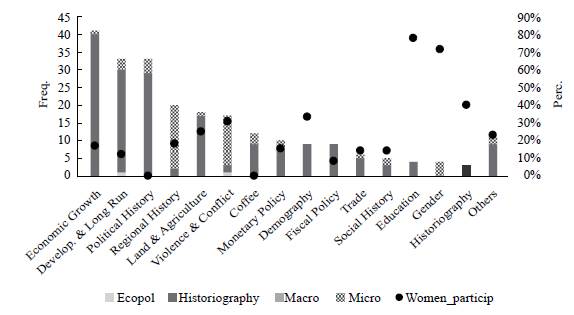

In Figure 2, we observe that 44.7% of the readings focus on macro processes such as economic growth, long-term development, and political history. This result is consistent with the objectives of the course that focus on long-term economic growth. In addition, other social and economic processes such as the participation of minorities (women, afro-Colombian, and native people) in economic history, have minimal not to say null coverage in the syllabus.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on the syllabus.

Figure 2 Readings and Female-Authored Readings According to CEH Topics and Categories

We estimate the participation of women authors in each category and find that female-authored references by topics are not homogeneous, there being a larger participation in topics such as gender 71.4% and education 77.8% and other categories in which there is no participation (coffee and political history).

According to the period of analysis, we disaggregate the readings to address whether female-authored literature is distributed homogeneously during those periods or if it follows a particular path (Table 3). In general, female-authored literature does not reach 30% of the readings per period. The greater participation of female-authored readings is for XXI century topics, followed by the XX century. Also, we found that the lowest participation of female-authored readings corresponds to the introductory section (8%), which includes works on the method and relevance of studying economic processes in the long-term and in historiographical debates. Furthermore, in the colonial period and in the 19th-century, readings written by women are below 20%. We interpret this distribution and participation of female-authored readings to a greater extent in the 20th century associated with two paths: on the one hand, the consolidation and consensus among scholars of traditional long-term history books that already have a long tradition in historiography, entirely written by men, at a time when male participation in the discipline prevailed. On the other hand, participation in readings regarding the 20th and 21st century's economic history can be interpreted by readings having to do with long-term economic development, whose focus is more recent in the discipline and more prone to women's participation.

Table 3 Participation of Men and Women in the Readings, According to Period

| Period/topic | Men (No.) | Men (%) | Women (No.) | Women (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction* | 23 | 92.0% | 2 | 8.0% | 25 |

| Colonial period** | 44 | 88.0% | 6 | 12.0% | 50 |

| 19th Century | 107 | 82.3% | 23 | 17.7% | 130 |

| 20th Century | 164 | 77.0% | 49 | 23.0% | 213 |

| 21st Century | 14 | 73.7% | 5 | 26.3% | 19 |

Note: * Introduction contains readings that introduce the course on topics such as historiography or methodology. ** Colonial period: 16th to early 19th centuries

Source: Author's own elaboration based on the syllabi.

The syllabi analysis shows an imbalanced participation of female-authored literature and a greater interest of women in the teaching field in including female-authored literature. We also find that gender issues are minimal in the syllabus, and the macro-historical approach fosters the invisibility of women in the course. Based on the two categories to assess gender bias, we can conclude that relevance is still marginal. The inclusion of gender topics is present in 15% of the syllabi, where labour discrimination stands out as a topic. Furthermore, this topic is the one with the greatest participation in female-authored literature. We suggest that part of the relevance has to do with the prevalence of a macro-historical perspective (74.5% of the topics). As for gender-bias in terms of participation, the proportion of female-authored literature remains marginal, from 0% to 32%. It is striking that there is still a syllabus with not a single female-authored work, accentuating the need for change. Gender equality is observed in terms of course instructors, with the same percentage of participation. Besides, CEH adheres to the concourse that female-instructors are more inclined to include female-authored literature than male instructors, which can implicitly affect the students' perception regarding who writes CEH. Moreover, the participation of female-authored readings is greater in the 20th and 21st-century analysis, suggesting an increase in women's participation in economic history and development. This approach has been dominant in economic history since the late 1990s and coincides with the greater participation of women in the discipline who are completing Master's and PhD degrees. The subsequent section aims to attend to the insight of economic historians in addressing their perception of potential gender bias in the subfield.

Insight of Economic Historians

We interviewed fourteen12 scholars either researching or teaching CEH to inquire on their perception concerning the question: is there any gender bias in the methodological approach, the topics analyzed, or the pedagogy both in researching and in teaching CEH? We present the results in accord with the two categories proposed above: relevance, participation, and perception.

Relevance: A Male Macro-Historical Process of Economics

As defined before, gender bias by relevance seeks to address how gender issues or topics are considered in the sub-field of economic history. In the interviews, the idea of relevance arose when most interviewees agreed that CEH is about macro-historical processes and a general overview of the past. Thus, they express a consensus on the importance of what they called the "traditional literature"13 leaving aside a micro-historical view that is more aware of and open to including gender issues. In other words, if the objectives of economic history are macro, then the historical process that surveys women's role in history will only appear when women have become part of a macro process. Women should not appear explicitly in the analysis and teaching of economic history since other population groups, including men, do not appear explicitly. As we observe, there is a dominance of the macro-historical vision that, as some suggest, is gender and social neutral but, taking into account how macro-history has been constructed, it follows a masculine vision. In short, the macro-history of economics is masculinized and reveals a gender bias in terms of relevance.

In general, men are receptive to the need for inclusion of gender topics in class in three ways: in including more compulsory readings written by women; in including specific topics having to do with women in CEH such as female participation in the independence period and the role of women in the early industry; and in promoting research activities that include topics with a gender approach.

For women scholars, the female perspective in the field and in class needs to be explicit, including examples but mainly including discussions on why women are invisible in some aspects of CEH, with the conviction that talking about it will provoke curiosity and before long new research issues. Almost all acknowledge that economic history with a female perspective is at the frontier of knowledge.

Therefore, if the syllabi and the assigned readings make women invisible, there is a clear need to transform this situation. How? First, by asking novel questions on development, poverty, inequality, and political economy, as those topics are broader in covering different actors, groups, and realities, including women. In this sense, this transformation must affect the CEH syllabus, including the macro-history approach, a micro viewpoint which includes women's history and women in CEH. In the same perspective, in some courses, professors are committed to quantitatively presenting the situation of women by means of historical series (school coverage and attendance, human development, labour access, among others). To present women in history is challenging as there is no historical data for the 19th century and before that. However, this is not a sufficiently strong reason to ignore women in CEH. Economic historians should take advantage of other disciplines (history, anthropology, sociology) to bring in women into the scene of history's events and processes thereby avoiding a gender bias relevance.

Yet, in terms of the CEH research topics, some researchers suggest the relevance of research in economic history, including a gendered outlook. As economic development presents profound structural processes that address women's changing conditions, the inclusion of a gender perspective is needed. For instance, demography contributes to a better understanding of women's participation in long-run economic performance and, as far as the statistics allow, the standard of life and anthropometry include a female perspective.

All interviewees, women and men, agree that the effort to attain a gender perspective and a feminist view in CEH both in research and in teaching must come from women and cannot be assumed by men in the initial steps. Men are in a position where gender issues are not their relevant concerns. There is a perception that efforts are also biased and must come from women interested in change.

In general, men interviewees say that it is misleading to avoid a gender view in class just because the female has had fewer leading roles in economic processes (Ministers, Governors, CEOs, among others). The opposite view suggests that it is not just a matter of being "relevant", but it is a matter of uncovering the different roles of women even in the private milieu (in the household, as mothers, wives, etc.).

Some suggest the standard approach of "objective science" (Haraway, 1988), is necessary and maintaining neutrality implies not taking any affirmative action towards any group, including women. The argument put forth here is that any affirmative action is idiosyncratic and might introduce a defect in academic analysis. One interviewee suggests that a gender perspective is in itself a bias, and as scholars, one should avoid it, making gender analysis unnecessary or irrelevant. By contrast, others suggest an active approach with affirmative actions toward any sources of discrimination, providing space for gender statements and favouring the construction of economic history with a female perspective (Nelson, 1995; Stromquist, 2003).

Therefore, part of the gender bias of relevance is associated with the prevalence of a macro-historical process in economic history, which generates the need for a debate within the field of economic history to discuss its objectives and broaden the perspective of economic history micro issues, including women's topics. In addition, gender bias in terms of relevance prevails through subtle issues such as the idea of science as "objective" or by justifying that given the low participation of women in economic decision-making positions, it is not relevant to include their history. Both arguments of "objective" science must be discussed within the discipline and the relevant activities of women.

Gender Bias in the CEH Field: Participation

Gender bias by participation attempts to address women and men's participation and if there are restrictions or stereotypes to foster balanced participation. All scholars interviewed say they hadn't thought about the need for participation of female readings in their classes. Men considered that the visibility of women in economic history will occur in a matter of time. As women increase their participation in education, changes will occur in academic production and faculty distribution. In synopsis, inertia might correct the gap between women and men, and there is no need to specifically "help" change the natural process. By contrast, for the younger generation of men and women, the debate on feminism and gender discrimination has been part of their formation. However, not all directly commit to a position on gender issues and even less so in class.

Conversation with scholars suggests two patterns: on one hand, the participation of female-authored literature when historiography decides that the work deserves a privileged space in the debate. On the other hand, some suggest no need to include readings from female authors deliberately, since this would be paternalistic behavior that runs contrary to academia. Both views are related and treat academia as impersonal, neutral, and objective. As Haraway (1988) suggests, knowledge is the struggle for an objective science above all when objectivity does not exist and depends upon where we are situated as researchers. Therefore, in a traditionally masculine discipline, the established knowledge gives men advantages, including in historiographic debate. To be part of the historiographic debate depends on who chooses the importance of the contribution and the participation of its course readings.

Interviewees suggest that the prevalence of macro-processes in CEH mainly refers to the participation of individuals in those processes (Public Servants, Ministers, Central Bank Directors), which in Colombia has mainly been a participation dominated by men with a low female inclusion. This view seems to legitimize the absence of women in CEH. Moreover, as Colombian macro-historical processes rely on macro-data, this might hide all the particularities of participating subjects (women, men, and other groups). For some of the interviewees, this was not an issue, as the data are objective, there is no need to question the nature of the data or the "realities" behind them.

The participation gender gap is also visible when referring to the economic field. All women interviewed agree that they are privileged as women (in the sense that they had education, work, family opportunities, and a voice). At the same time, they acknowledge the persistence of masculine culture in both economics and Colombian society. In their view, economics is still a male-dominated field in its composition reflecting the type of concerns the discipline is analysing and responding to as well as the low interest regarding gender issues (around 70% of undergraduate students are male and among scholars only around 17% are female professors).

On the other hand, the men interviewed agree that they have normalized the way CEH is taught or written and they have been in a position of privilege that might "blind and hide reality". They say that the privileges result from a culture where men are still at the center. However, transformation has a female voice. Some say "mea culpa; I was unaware of the necessity of including women in readings, examples, or anything else". For men, the awareness with regards to gender topics occurs at a slower pace; this view is associated with Brown's affirmations (2000).

All the interviewees agreed that in the field of history more female-historians are incorporating economics analysis in their research, consequently history is more open to female-researchers including researchers in economic history. When asked about what might explain this vast difference between economic historians and historians who include the economics viewpoint, they suggest that it is a matter of tradition in history degree programmes rather than in economics programmes because history has had a longer tradition in Colombia. However, this view is misconstrued since history as professional education arises almost simultaneously as economics. We believe that the vast gap in the participation of females in history and economics started with the enrollment in economics (around 30% women), then deciding to choose an academic and research career (less than 20% of faculty members are women) in accord with Bayer and Rouse (2016) and their explanation of diversity barriers in economics. And even before, as the stereotype of "math as the appropriate field for men" and "language as that for women" could bias and restrict women's choice of economics because of its high quantitative content.

One woman interviewee perceives a gender imbalance in academic jobs. In fact, she explains that women in academia are tasked with more academic-administrative duties compared to their male peers. These tasks result from the stereotype that "women are good managers, are more responsible, and their discipline is beneficial for the organization".

To sum up, there seems to be a consensus regarding the idea that correcting gender bias of participation is a matter of time. This bias responds to the existing imbalance in the discipline of Economic History and might be corrected by time and by the explicit inclusion of readings of female authorship and topics concerning women in the courses and by, at least, becoming aware of the unbalanced gender participation by discussing it in class.

FINAL REMARKS

This paper addresses gender bias in CEH from two perspectives: relevance and participation. In terms of relevance, we find that women teaching CEH include gender economics and gender discussions in their syllabi, patterns not observed in the syllabi written by men. Based on the interviews, we confirm that this may be associated with a particular interest of female professors in gender issues and discussions. However, the gap between women's and men's readings, the almost absence of topics on gender issues, and the general idea that economic history is about macro-processes, reveals that CEH is taught with women conserving a very passive almost invisible voice. This, according to the literature, outlines the hidden curriculum that unconsciously preserves gender biases and stereotypes.

Furthermore, the preponderance of macro-historical process analysis in CEH makes it difficult to include gender or women's issues in the analysis. Therefore, economic history in Colombia, at least, needs an epistemological discussion to debate regarding the inclusion of micro-historical process analysis as a relevant part of economic history analysis. This discussion may broaden CEH to not only include women but also other minorities and traditional outsiders of economic history (peasants, native communities, afro-Colombians, among others). We observed gender bias in the unseen situations that preserve stereotypes or scholars' positions regarding the field. We find that, although there is an idea that the field should be neutral and objective without any affirmative actions towards women, there is room to discuss the relevance of including women topics and perspectives in CEH. This is not a closed debate, on the contrary, it is an ongoing discussion that should be fostered in order to achieve favorable changes toward the reduction of biases. Despite a majority pointing out that women should lead this change, several men indicate that they would align with this process and favorable changes in teaching need to be promoted by both men and women.

In terms of a gender bias in participation, we find that female-authored readings are assigned more frequently by female professors (25.9%) than by male professors (11.3%). We confirmed that this occurs because female instructors are more apprehensive of including their peers' academic production and make them more visible, although not all women share this option. Besides, CEH has a macro-process seal that has also silenced the voice of female participation in history. The proportion of female-authored literature is marginal (9.4%) compared to male-authored literature (77.5%), showing the need to include more readings and references of female-authored works. Examining CEH syllabi, we find that not only women are underrepresented but also unvoiced. Participation also requires changes in the working environmental conditions of women in academics. As women suggest, there are more pressures for women to be fully dedicated to their research agenda which is a restraint to their academic production. Transformation of the field should as well rethink not only how to include more female authored literature in the syllabus but also how to provide the same conditions for men and women who dedicate themselves to this academic field.