INTRODUCTION

Maria da Conceição de Almeida Tavares is one of the brightest minds in Brazilian and Latin American critical thinking. A "rebellious, restless and creative mind," Bielschowsky would say (2011, p. 24). Possas (2001, p. 389) states that: "she has been one of the most influential economists in Brazilian economic thought since the 1960s, especially the heterodox". Her contributions extend to a wide variety of fields, including the inauguration of an economic theory at the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC); her role as a professor and mentor to great Brazilian intellectuals and politicians at the Institute of Economics of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP); and her insertion into Brazilian politics as a congresswoman from the state of Rio de Janeiro from 1995 to1999.

Maria da Conceição Tavares, born in Anadia, Portugal, on April 24, 1930, has reached her 90th birthday. These lines are proposed as a tribute to her professional career and her vast contribution as a critical intellectual with a permanent commitment to the development of Brazil and the Latin American region. Letting her clear, precise and contemporary voice be heard to diagnose the main problem that today still determines (and has done so structurally) the development of Brazil and Latin America, namely: "the distribution of income and property".

In May 2019, I interviewed1 Maria da Conceição Tavares at her residence in Rio de Janeiro. Getting to know her, getting to meet her face to face and talk with her was one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. Maria da Conceição Tavares has been my source of inspiration in the field of Latin American political economics since I first heard her provocative and enlightening lecture on the future of Brazil on the Praia Vermelha university campus at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, on my first visit to Brazil, back in 2003. The impact she had on me impelled me to find an opportunity to meet, talk and have a coffee together. There she was in front of me about to converse and share some coffee.

The meeting was held on the occasion of the VII Latin American Conference on the History of Economic Thought, held at the Federal University of Paraná in Curitiba in November 2019. I invited her to come, as we organized a special session on ECLAC's 70 years of economic thought, and she would be the present time memory of this history. However, such a long journey was difficult due to her advanced age, so I decided to travel to chat with her and convey her message. What follows is an excerpt from that conversation on that warm autumn afternoon in Rio.

The purpose of the full interview was to explore, in Tavares' experience, how ideas and proposals of economic policy (associated with Latin American structuralists) penetrated each institution in which she participated (ECLAC, UFRJ - UNICAMP and the Legislative Branch) and whether the interaction between such institutions favoured greater adherence to these ideas. Gender was addressed in our conversation as we explored her professional career and personal experience, given that Maria da Conceição has been a "female reference" in a predominantly male economic professional environment.

DIALOGUES WITH MARIA DA CONCEIÇÃO TAVARES

The interview focused on ECLAC to delve into Tavares' perspectives on its main contributions to Latin American and world economic thought, the main theoretical aspects of the structuralist school, Tavares' main legacy within that school, and the region's major present development challenge from a structuralist perspective. Tavares set forth that this challenge continues to be chronic structural heterogeneity, fueled by inequality in the distribution of income and wealth. We discussed ECLAC's adherence since the 1960s to economic policy recommendations to overcome structural heterogeneity and improve income and wealth distribution in Brazil and in the region proposed.

Along these lines, in an official ECLAC document from 1963, it was stated that:

Political leaders and social science specialists in the region have never been more in agreement on the general policy needed for sustainable development [...] Agrarian reform, diversified industrialization and the reduction of extreme inequalities in income distribution are accepted today as essential elements of a coordinated national policy. (ECLAC, 1963, p. 3)

Bielschowsky (2000) had already defined the 1960s as the decade in which the concern with distribution gained importance in ECLAC's thought. Furtado (1961, 1968) and Prebisch (1963) argued that the distribution problem caused by the concentration of income in Brazil and the countries of the region was the main factor hindering development. Recently, Curado and Fernández (2019) briefly periodized the relevance of the distributive issue in ECLAC's thought and highlighted the 1960s, in step with Bielschowsky. They also claim that in the last decade, which began in 2010, the distributive issue has become the focus of the debate for two reasons. The first, because it provides policies with a rights-based approach; and the second, because equality is a condition for setting forth a development model focused on innovation and learning, with positive effects on productivity, environmental sustainability, the spread of the information society and the strengthening of democracy and full citizenship. In this sense, the improvement in distribution would become an essential aspect of development. Or to put it another way, the concentration of income and wealth are considered obstacles to economic growth and development.

Below are some extracts from the interview, which was carried out in Portuguese2:

VLF: Maria, what is ECLAC's main contribution to the history of Latin American economic thought and also to the history of world economic thought?

MCT: ECLAC's contribution to economic thought in general, both for Latin America and the world, was the introduction of the "centre-periphery3" idea. And it was Prebisch who introduced it. He used the expression. Before him it was not usual for someone to talk about a centre and a periphery. And he included Latin America in the periphery at that time.

VLF:.Could you expand on some other elements of that idea of duality?

MCL: ECLAC basically introduced the idea of structural heterogeneity. And it was Aníbal Pinto who introduced it. That is an important idea. But duality is not his idea, duality is an English idea4. Structural heterogeneity is Aníbal Pinto's5, because he thinks that there is no duality in our case, that Latin America is characterized by structural heterogeneity.

VLF: I understand, but this idea of a "centre-periphery" has an element of duality, that was more remarkable especially for Prebisch and Furtado.

MCT: Yes, that idea of "centre-periphery" was introduced by Prebisch and Celso Furtado developed it. It's based on the ECLAC school in general, let's say.

VLF: ECLAC incorporates elements of the classical economists, of Keynes, of Marx, some Schumpeterian elements. It is nourished by the classics and uses them to understand the processes in Latin America. But what do you think its main contribution to the history of economic thought could be? Including your contribution to analysing the case of Latin America... Furtado's ideas linked to the amount of low-skilled labour, or that this would lead to stagnation.

MCT: I'm against the idea of stagnation and I wrote against Furtado. I'm in favour of the idea of import substitution, which is my crop. It's just that the idea of stagnation is meaningless. Brazil has never been a stagnant country. And Furtado was born here, he worked here. So it's fantastic that he invented the idea of stagnation for a country that has never had stagnation.

VLF: And you get to illustrate afterwards that there won't be any stagnation, but then you make an incorporation. And you wrote an article, with Serra.

MCT: I wrote an article called "Beyond Stagnation6" with Serra.

VLF: There you express a stronger disagreement with master Celso Furtado.

MCT: That's true, in fact it's one of the strongest, let's say. Because his stagna-tionism never convinced me. And I made a point of stating my position in this article. I even wrote to him afterwards, apologizing. And he went... "That's okay." It's not, because you are my master... and he said, "No, your master is long dead." He thought my master was Marx (laughs).

VLF: And was he not?

MCT: Marx, Keynes, no doubt... The classics.

VLF: You precisely incorporate this rather Marxist question into Latin American thought. Because what was most compelling were the Keynesian and Schumpet-erian ideas. But the Marxist question of the cycle, was it you who introduced it?

MCT: That's right. I was the one who introduced it.

VLF: These contributions were made to analyse the case of Latin America and incorporate into the history of ECLAC's economic thought of these 70 years. This idea of "centre-periphery". Is that what you believe to be the main contribution?

MCT: "That's the relationship that was maintained. One that continues. The centres are there and we're still on the periphery. Until proven otherwise, there is no central country in Latin America."

VLF: What about the new centre? The question of new perspectives with the current reality with developing Asia, with China? How should we think about this?

MCT: But that's a new centre right there. In the previous case first it was England, the centre of the world economy, then the United States and now China has entered the dance too. I think its going to be... It (China) is already the centre of Asia, no doubt. And it is a nearly capitalist centre. It hasn't yet become capitalist because it has a lot of state intervention. But it's the most important centre of Asia.

VLF: This new centre (China) is changing the international scenario.

MCT: It has had a powerful influence.

VLF: There are authors who say that patterns of consumption have changed with the rise of China and Developing Asia because they produce consumer goods that are accessible to the poorest population.

MCT: This is a change because previously consumerism was only for the middle classes and now it is also for the masses.

VLF: Maria, what was your contribution to ECLAC here in Brazil and Chile?

MCT: It was "Import Substitution7", that was my first contribution. Then in Chile it was "Beyond Stagnation" (1971), at ECLAC. In Chile I analysed the other Latin American countries, including Peru. And I worked with the monetary element, I included this when I was over there, in Chile. And I lectured at Escolatina.

VLF: If you could, explain in a few words what these contributions are, what are these "Import Substitution" and "Beyond Stagnation" texts.

MCT: "Beyond Stagnation" is basically rejecting Furtado's thesis that we were heading for stagnation. That is Furtado's thesis8.

...Because we were not heading for any stagnation, we were always a dynamic economy, so I don't know where he got stagnation from9.

VLF: And what was your reasoning in supporting that there would be no stagnation?

MCT: There was no stagnation, there never was, we were always a dynamic economy. I don't know where he got stagnation from. How he invented stagnation is what I don't know. We were never a stagnant economy.

VLF: But the idea that stagnation could come from the fact that the consumer market, or the exploitation of the working class, would not allow the expansion of consumption...

MCT: No, that's silly. It is simply not possible to include the consumption of the middle class, but the consumption of the popular classes has expanded brutally. Mass consumption is a fact in Brazil. And it's totally expanded.

[...] "My explanation is that there is a cycle, but not stagnation. And the cycle is not about marginal capital efficiency, it is about the cyclical trends of capitalist economies in general. So the idea of stagnation is an incorrect idea in Furtado. If there is a country where there is no tradition of stagnation it is Brazil. I don't know where he got stagnation from. I think he thought it would happen, but he thought it was a fait accompli that it was coming. He didn't say maybe, he said it was going to happen, and it never did".

VLF: If you had to leave a message for people, researchers, who are thinking about the History of Latin American Economic Thought... What's the main challenge?

MCT: The biggest problem in Latin America is not stagnation, but income distribution, which is very bad. That's the problem. That gives way to structural heterogeneity. This poor income distribution creates a structural heterogeneity based on the point of view of consumption and production.

That is our problem, the problem of heterogeneity, not the problem of stagnation. VLF: That element is from Aníbal Pinto...

MCT: Yeah, that' s where it comes from. He was my master. All my heretical thinking I inherited from him. (laughs)

Aníbal Pinto's thought was very rich. It's true that I later contributed to spreading it, but he had a big fan base here too. He spent several years in Brazil, he was Director of the ECLAC-BNDE Center and liked Brazil very much, so he was interested. He was very important to me. ECLAC alone would not have made me so heretical. I owe that to Aníbal Pinto. He was a heretic, he was a heterodox.

VLF: And this idea of structural heterogeneity was later rescued and synthesized by Octavio Rodríguez...

MCT: Yes, but that was because of Aníbal Pinto.

VLF: And then something comes up where the causality is unknown. Because you talked about income distribution and heterogeneity... And this idea that income distribution is the central problem, is the key to structural heterogeneity. For whom should we produce?

MCT: That's right.

VLF: And the Chinese, it seems that they would have consumated the idea of producing for everyone. For the lower income classes.

MCT: That's right. It's mass consumption there right from the start. They don't seem to have a serious problem with income distribution, maybe wealth, but that I don't know, there's no data. I don't have data on China regarding the distribution of wealth. But the (distribution) of income was not a problem. They are a country of mass consumption from the beginning. We're not.

VLF: And is that the key question for you? The main challenge, the main element to think about the Latin American reality?

MCT: It's this income distribution thing, which is bad. It's the main one and it has to do with the concentration of the property.

VLF: What would be your message for researchers working on the history of economic thought? What would the main challenge be for Latin America in this national and international scenario, along with the presence of China, given Brazil's stage of development?

MCT: I think that as far as the presence of China is concerned there is no problem, because we are not competing with China nor are we doing import substitution of Chinese products because they were never exporters for us. They are more of a direct investment. They're not direct exporters to us. They do not export Chinese products. Is that clear?

VLF: Are you talking about what is produced here with Chinese Foreign Investment?

MCT: That' s right.

Which is completely different. This is not import substitution, it's investment substitution.

VLF: ...But even if it is growing? Because China is the main investor and the main importer in Brazil today.

MCT: Yeah, it's growing.

VLF: And what is the main problem or challenge to be considered in Brazil and Latin America?

MCT: It's income distribution. That's what's difficult. Because the problem of income distribution is on one hand the salary, because wages are very heterogeneous. Poor people's wages are one thing, middle class wages are another, rich people's wages are something else. The same as property. We have a great concentration of property. And that worsens the income distribution.

VLF: And this concentration of income is totally linked to Aníbal Pinto's idea of structural heterogeneity, which you also spent a lot of time working on at ECLAC.

MCL: Right. Quite so.

VLF: So the main challenge to think about in Latin America and Brazil today would be...

MCL: It's still income distribution... More than growth. Growth, some countries have managed to grow, others have not, but for different reasons let's say. Now, with respect to improving income distribution I have no news that any country in Latin America has improved anything. That is the worst. And therefore, heterogeneity will continue.

VLF: And why have the most progressive Latin American countries in recent years, the governments of the early 21st century (Lula, Néstor Kirchner in Argentina) failed to improve income and wealth distribution?

MCT: They tried, but imagine. It's just that messing with property is no joke. People can mess with anything, but not with property. Property is sacred, "to them."

They've never been able to redistribute property, or make laws that promote equality. The dominant spaces here don't toast to that service. In Latin America as a whole, including Mexico which has made a popular revolution, and yet income distribution also stinks. That's the main problem in Latin America. It has a very unequal distribution of income and property. And it doesn't develop because you can't equalize the situation of the bottom with those at the top.

VLF: And in Brazil it's been getting worse. And this concentration of the richest one percent...

MCT: Of course, it's still the same misfortune and the ones underneath the same misfortune.

VLF: Do you have a proposition in which you would say... It would have to be done this way in order to solve the situation...

MCT: Yeah, but everything would have to be undertaken, land reform, property reform, anyway.

VLF: What about the reforms implemented at the original ECLAC to change the production structure?

MCT: Right. But it turns out that ECLAC proposed reforms that were never made. It's one thing to propose and another for the ruling class to push it through. And the dominant class has never taken up the ideas of ECLAC reformers. When it did, it was conservative, not reformist.

VLF: And at some point you say that the Brazilian development program is a modernization10...

MCT: Yes. Because it is, a conservative modernization. VLF: So you don't think this is real development?

MCT: No, it's not that it's not a real development, it's that the development is not egalitarian, it's a heterogeneous development. But it's development anyway. You can't say it's not because it is. It's not just growth, it's productive development as well. But it's unequal, it's heterogeneous.

VLF: And do you think it's possible to reform the distribution of income and wealth in capitalism?

MCT: Not in underdeveloped capitalism. I don't know of any cases, at least. In developed capitalism, yes, because they made reforms. But they had active unions, left-wing political parties. Not here. Here we never had that. We had left-wing minorities and minorities in the unions, but they were never active or dominant on the political scene. While in Europe and the United States they were.

VLF: One last question. As a woman, throughout your professional life, as a teacher, at CEPAL, at the university... did you feel that anything was different because you were a woman? Facing all these men at CEPAL...

MCT: No. But I am very aggressive, so they respected me. I'm intelligent, I'm aggressive, combative.... So, it's not easy to curb me, you know. It's not easy for them curb me, like this. They never managed to curb me... (laughs)

VLF: What about other women? Why aren't there many women in those spheres...

MCT: There is no reason why there aren't, you know. They are not aggressive, but I am!

VLF: But then, in order for a woman to be heard, one has to be aggressive?

MCT: Ahhh, you have to be aggressive. I think...Here in this country, those who are soft can't survive. You have to have a combative approach, otherwise you won't make it. Think about it.

VLF: And at CEPAL?

MCT: But then it is not important because there is no executive...it was different. And I was the only female economist at CEPAL. So, I had sympathy in general. And Aníbal Pinto, who voted me into CEPAL, as he was a progressive...And I worked with him...

VLF: And he defended you?

MCT: He always defended me, from that point on. I went there at his invitation, of course. I owe everything to Aníbal Pinto. If it wasn't for old Aníbal I would be in school, teaching. He was the one who launched me into the world. Old friend. He took me to CEPAL in Chile. He is my master.

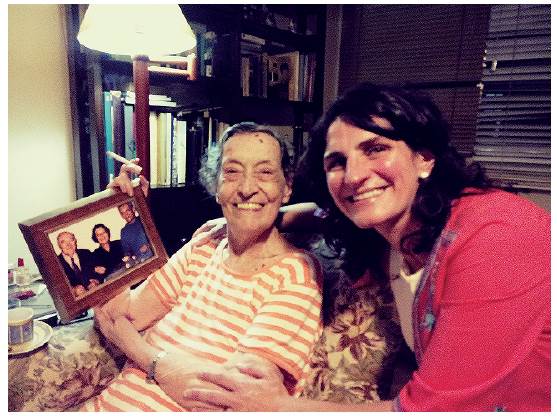

... Look at my two masters here (in the photo), Aníbal Pinto and Celso Furtado (see Figure 1).

THE BASES OF ECLAC STRUCTURALIST THOUGHT

The Centre-Periphery System, Terms of Trade Deterioration and Structural Heterogeneity

At the historical moment when the founding document of CEPAL11 was drafted in 1949, ideas on international trade based on David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage prevailed (Bielschowsky, 2000) This theory asserted that through trade, exchange, via productive specialization in sectors where economies have lower relative labour costs, countries could reduce or eliminate unequal income distribution and thus achieve greater productive and trade efficiency.

However, Prebisch, analysing the reality of Latin America - as a member of the periphery - criticizes this theory, suggesting that the "slow and uneven" diffusion of technical progress on an international scale gives rise to differences in the degrees of development of countries. Prebisch (1949) expresses it as follows:

The flaw in this assumption is that of generalizing from the particular. If by "the community" only the great industrial countries are meant, it is indeed true that the benefits of technical progress are gradually distributed among all social groups and classes. If, however, the concept of the community is extended to include the periphery of the world economy, a serious error is implicit in the generalization. The enormous benefits that derive from the increased productivity have not reached the periphery in a measure comparable to that obtained by the peoples of the great industrial countries. Hence, the outstanding differences between the standards of living of the masses of the former and the latter and the manifest discrepancies between their respective abilities to accumulate capital, since the margin of saving depends primarily on increased productivity. (in ECLAC, 2016, p. 46)

The conclusion that there is a technological gap between central and peripheral countries is accompanied by the observation that this is closely related to productivity and the terms of trade. For Prebisch there is an uneven penetration of technical progress among sectors of the periphery, which generates within peripheral countries persistent differences in their productivities. Thus, given that technology only penetrates in the raw material exporting sectors and not in the other (underdeveloped) sectors, dual systems are generated in the periphery, which hinder the industrialization process in the periphery. This is what he observed when analyzing the evolution of world economy between 1876 and 1947:

Speaking generally, technical progress seems to have been greater in industry than in the primary production of peripheral countries, as was pointed out in a recent study on price relations (of The Board of Trade). Consequently, if prices had been reduced in proportion to increasing productivity, the reduction should have been less in the case of primary products than in that of manufactures, so that as the disparity between productivities increased, the price relationship between the two should have shown a steady improvement in favour of the countries of the periphery. (Prebisch, 1949, in ECLAC, 2016, p. 51)

Prebisch demonstrates that the drop in the international prices of primary products is not accompanied by a similar dynamic in the prices of industrial products. This fact contradicts the traditional theory, which is unable to explain why the improvement in industrial productivity does not translate into a reduction in the prices of industrial products.

Therefore, countries that have an external insertion based on the export of primary goods would find an obstacle to their growth, since the foreign exchange derived from exports loses relative to their purchasing power. This imbalance (to the periphery's disadvantage) between the price relation of exports and imports, which ends up obstructing the growth and development potential of peripheral countries, is known as deterioration of the terms of trade. Prebisch, when analysing the evolution of the Argentine economy and dealing with the development problems of Latin American countries, concludes:

First: Prices have not fallen concomitantly with technical progress, since, while on the one hand, costs tended to decrease as a result of higher productivity, on the other, the income of entrepreneurs and productive factors increased. When income increased more than productivity, prices rose instead of falling.

Second: Had the rise in income, in the industrial centres and the periphery, been proportionate to the increase in their respective productivity, the price relation between primary and manufactured products would have been the same as if prices had fallen in strict proportion to productivity. Given the higher productivity of industry, the price relation would have moved in favour of the primary products.

Third: Since, as we have seen, the ratio actually moved against primary products in the period between the 1870's and the 1930's, it is evident that in the centre the income of entrepreneurs and of productive factors increased relatively more than productivity, whereas in the periphery the increase in income was less than that in productivity.

In other words, while the centres kept the whole benefit of the technical development of their industries, the peripheral countries transferred to them a share of the fruits of their own technical progress. (Prebisch 1949, in ECLAC, 2016, p. 53)

The above excerpt challenges the traditional theory of international trade based on Ricardian comparative advantages and states that there is no "spillover effect" resulting from the technical progress of capitalist economies by means of productive improvements and reduction of prices of industrial products. Moreover, if there is a spillover effect or transfer of the fruition of technical progress, it will be in the opposite direction, from the periphery to the centre, as expressed in the preceeding paragraph. These postulates confirm a relationship between economic growth and the external restriction generated by the asymmetry in income elasticity of exports and imports in countries exporting raw materials and industrial products, which is also reflected in the relationship between central and peripheral countries.

The centre-periphery system is established based on the insertion of countries in the international division of labour in which those who were the first to enter the industrialization process, such as England, the European countries, the United States and Japan, present a dominion in terms of the creation and diffusion of technical progress. Technical progress that reaches the other countries, which remain inserted in the world economy through the primary economy (production of food and raw materials), in a "slow and uneven" manner. The former, countries considered to be large industrial centers because of their predominance in controlling the advances of technical progress and the improvement of productivity, are the central countries. The latter, that vast set of countries that produce primary goods, supplies and food which are useful to the central economies, guarantee their food and industrial production at a lower cost, these are the peripheral economies. In this last group, clearly, were the Latin American countries, the focus of Prebisch's diagnosis.

The key point is that this "slow and uneven" dissemination of technical progress between central and peripheral countries conditions so that such a relationship is maintained over time. That is, as long as the peripheral countries remain inserted in the international division of labour, producing food, raw materials and commodities and implementing in these sectors the advances in technical progress developed by the central countries, there will be an increase in productivity, an increase in production and a reduction in the prices of food, raw materials and commodities that will benefit the purchasing countries (central countries, large industrial centers). However, the rewards of the implementation of technical progress generated in the peripheral economies in terms of increased production and price reductions remain in the central countries and not in the peripheral economies.

Gurrieri summarizes that Prebisch considers that the centre-periphery system operated to satisfy the needs and interests of the industrial centres (where technical progress originated and was rapidly diffused); that the peripheral countries insert themselves in the system according to the extent that they can serve those interests and needs, supplying raw materials or food and receiving manufactured products and capital; and that this insertion (of the periphery) is insufficient to equalize the income level of the periphery with that of the centres. This insertion "imposes two negative features on the peripheral productive structure -structural heterogeneity and specialization- as a consequence of the slow and irregular12 penetration of technical progress.

Hence, three inequalities emerge between the centres and the peripheries. The first, in the position and function they occupy within the world system, the centre being the provider and the periphery the absorber of technical progress. The second, in their productive structures, with the centre having a diversified and homogeneous productive structure, while the periphery is specialized and heterogeneous. The third, in their average levels of productivity and income, being high in the centres and low in the peripheries13. (Gurrieri, 2011, p. 21)

Structural heterogeneity, understood as the vicious circle that creates and reinforces divergences between central and peripheral countries in productive structure, labor market structure, growth potential, per-capita income and wages, had already been present in the foundational writings of Prebisch and Furtado when the agrarian-exporting economies were analysed. However, Aníbal Pinto incorporates an analysis of internal heterogeneities in the regions of the countries and following the beginning of the industrialization process. Pinto begins based on the observation that the fruits of technical progress tend to be concentrated in only a few sectors, both in terms of income distribution among social classes and in terms of distribution among sectors (strata) and among regions of the same country.

Thus, structural heterogeneity derives from the existence of a heterogeneous productive structure, in which a few high productivity sectors (linked to the exploitation of natural comparative advantages) coexist with many low productivity sectors (intensive in low-skill labour).

Additionally, after analysing the results of the impact of industrialization on the structural heterogeneity of the countries in the region, he strengthens his argument concerning the reproduction of the old structural heterogeneity that prevailed in the agrarian-export period. The central problem would derive from the existing difficulty in the industrial centres of the periphery to interact with the traditional obsolete sectors. "The main aspect is not that they are distinguished areas, but that the "irradiation" from the exporting locus to the "interior" [hinterland]14 is null or minimal. The first (the export complex) grows from and outward, while the second "vegetates" without other stimuli, except the "endogenous" ones. (Pinto, 1970, p. 1). The main problem is that, from this perspective, industrialization would not eliminate structural heterogeneity, but only modify its shape15 . This point was central: although there was economic growth, the underdevelopment of the region would persist. This question led Pinto to inquire about new styles of development, with greater social justice and aimed at reducing structural heterogeneity.

Stagnation versus Dynamism: "Beyond Stagnation"

Maria da Conceição Tavares first contributed to the structuralist thought of CEPAL in 1964, with "The Growth and Decline of Import Substitution in Brazil". In the article, she argues that industrialization would not solve per se the problem of scarcity of foreign exchange in the peripheral countries and in Brazil in particular, because the import substitution process, although it transformed the productive structure for some more qualified sectors, would fall into a balance of payments strangulation, since production for the internal market (inward) implied the demand for foreign capital goods, which ended up sustaining the inequality in the balance of payments, which is structural in the case of the countries of the region.

Prebisch, in the foundational documents, already expressed this concern, and affirmed that this situation would be maintained until the process of industrialization by import substitution was completed. However, Tavares' formulation is precise in explaining that there was a particular substitution dynamic, specific to the countries of the region, due to the way they react to the successive balance of payments bottlenecks throughout this process. In other words, the import substitution process, which would progressively evolve from the easiest to install sectors (not very demanding in terms of technology, capital and scale) to the most sophisticated and demanding sectors, would lead to a process of growth, labour absorption and consumption that would accompany the process and, therefore, would imply an alteration in the composition of imports, but not a reduction. (Bielschowsky, 2000, p. 29). It is also worth noting that this process would not be harmful to the centre, since it would maintain a dynamic cycle of external demand and lower equilibrium prices.

Although this initial contribution was relevant, the text that placed her at the center of the debate in CEPAL was "Beyond stagnation: a discussion on the nature of recent development in Brazil". The text was developed at CEPAL's own office in Chile, coauthored with José Serra and was presented at an international seminar in November 1970 and published in December 1971.

"Beyond stagnation" is central because it helped in formulating arguments to interpret the possible "styles" of development in the countries of the region, CEPAL's analytical axis in the 1970s. It is also central because it attacks on solid ground the stagnationist theses that spread during the 1960s regarding the exhaustion of the substitute model in the region, in particular Celso Furtado's thesis published in 1969 on "Development and stagnation in Latin America: a structuralist approach".

The thesis "Beyond stagnation" analyses and interprets the process of crisis and recovery of the Brazilian economy in the mid-1960s and, based on this, evidences that there are particular aspects of the Brazilian economic development style, from which derive specific ways of functioning of a capitalist economy in which there occur: processes of expansion, diffusion and incorporation of technical progress and, simultaneously, economic reconcentration. (Tavares & Serra, 1971, pp. 591-592). That is, for Tavares and Serra (1971):

In the Brazilian case, in particular, despite the fact that the economy has developed in an extremely unequal way, deepening a set of differences related to consumption and productivity, it has been possible to establish a scheme that allows the generation of internal sources of stimulus and expansion, which confers dynamism to the system. In this sense, it can be said that while Brazilian capitalism develops in a satisfactory way, the nation, the majority of the population, remains in conditions of great economic deprivation, and this, to a large extent, due to the dynamism of the system, or even to the type of dynamism that animates it. (p. 593)

Therefore, the Brazilian economy is a particular and possible case in Latin America in which a period of economic dynamism occurs, with high rates of economic growth and high investment that characterizes the import substituting advance in more sophisticated sectors, but with great social injustices, that for the authors (Tavares and Serra) were generated by wage compression.

The main difference between Furtado (stagnationism) and Tavares and Serra (concentrating "perverse" dynamism) concerns the perception of the crisis of the early 1960s in Brazil. While Furtado links economic stagnation to the loss of dynamism in the industrialization process supported by import substitution and therefore is concerned with the evolution and behaviour of the demand structure, which is dependent, in its turn, on income distribution. Tavares and Serra consider that the crisis that accompanies the exhaustion of the substitution process represents for some countries, among which Brazil is included, a transition situation to a new scheme of capitalist development. This new scheme could present "dynamic characteristics and at the same time reinforce some aspects of the substitutive growth "model" in its more advanced stages, such as social exclusion, space concentration and the stalling of certain economic subsectors in terms of productivity levels" (Tavares & Serra, 1971 p. 592). Additionally, it is possible to argue that Furtado's analysis is based on the idea that there would be a low product/capital ratio due to the substitutive process, which would discourage investment and contribute to maintaining the economy's stagnation. However, Tavares and Serra consider that the product/capital ratio is a result of the productive process and that the relevant variable to encourage investment is the surplus value rate (or the rate of exploitation).

Finally, it is important to note that in Ricardo Bielschowsky's presentation of the text "Beyond Stagnation", he sets forth that the article was written "at the CEPAL headquarters in Chile under the direct influence of her master Aníbal Pinto, who in his already influential thesis of structural heterogeneity, had helped to pave the way for the idea". (Bieschowsky, 2000, p. 49). As we have previously outlined, the idea of structural heterogeneity perfected by Pinto, made it possible to understand the coexistence of a process of import substituting industrialization without improving the structural heterogeneity of the economies of the region. Pinto in 1976 would write one of the fundamental texts on "styles" of development of ECLAC thought in "Notes on styles of development in Latin America".

FINAL REFLECTIONS ON THE INTERVIEW

The dialogue with Maria da Conceição Tavares was a transforming and provocative experience. Because of the knowledge she shared, because of her long-term vision, because she defined in a few words what is still the main obstacle to the development of the Latin American region: the terrible distribution of wealth and property. And for realizing that the structural reforms historically suggested by ECLAC are still necessary: agrarian, property, financial, tax, educational, and technological reforms, as well as those that reduce the structural heterogeneity of the countries in the region.

Although the above suggests a certain thematic similarity to the problem of Latin American underdevelopment over the decades, the perception of gender issues seems to have had a more notable evolution and this shows a generational shift that is expressed in the interview.

One of the main contradictions that emerged during the interview was that when asked about the gender issue Maria da Conceição replied that she never felt belittled, because as she was "aggressive" (an expression she used several times throughout the interview) everyone respected her.

The perception that Maria da Conceição had of herself and of the economists that were her contemporaries seemed to have a negative gender connotation - speaking in a subtle way, let's remember the expression: "to be heard a woman has to be aggressive". Or another response, when she argues that her proximity to Aníbal Pinto kept her protected, from which it can be inferred that, with a reference man in the professional ambit, it is more difficult to be attacked.

Regarding the use of the adjective "aggressive" I want to make clear the delimitation that was given to the concept, to avoid any misinterpretation. The Houaiss dictionary of synonyms and antonyms gives three meanings for aggressive, that of "combative", "provocative" and "violent". Clearly, Maria da Conceição called herself aggressive in the sense of "combative" and "provocative" when presenting and defending her ideas in favour of making Brazil a more developed and just country. It is underscored that at no time did she refer to aggressive as violent.

Hence, it is possible to state that Tavares' answer clearly exposes a gender issue and her role or her search for a way to relate in a historically male environment. A generational aspect of the gender issue also emerges from the interview, since she does not see it as a gender issue, but as a "condition" for any woman of her time.

Tavares' lack of perception regarding the treatment she received for being a woman is also evident in a part of the interview, which was not presented in this article, when she is questioned about why she never occupied a relevant position in the executive branch (Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Planning, National Bank of Economic and Social Development, Central Bank, Institute of Applied Economic Research). Although she expresses that she has never felt a difference in treatment, it is striking that most men of her intellectual greatness, including many who were her students, have reached these positions.

Lastly, it is important to highlight the value of using this type of source in economic science. Oral history records rescue some spontaneous nuances that are very difficult to capture in another type of written record, in which there is more time to reflect, but also to construct more standardized answers or that adhere to a more logical approach.