We find ourselves, as so often happens in these ugly police cases, having to prove that acts of discrimination are exactly that - discrimination.

-Bill Spriggs (2020)

INTRODUCTION

In June 2020 -in the middle of the Black Lives Matters (BLM) Movement- the American Economic Association (AEA) issued a statement claiming that racism and discrimination are in force in the United States, and that "its impact on the profession and economic discipline is only beginning to be understood" (American Economic Association, 2020, para. 3). Likewise, economists such as Bill Spriggs (2020) and Lisa Cook (Cook & Opoku-Agyeman, 2019; Cook & Gerson, 2019) have joined the voices that point out that this problem is systemic and that it should not continue to be invisible. With an open letter, Spriggs signalled that many economists have remained silent after witnessing evident acts of discrimination against minorities in U.S. departments of economics, even though they claim to be in favour of a more inclusive discipline (Spriggs, 2020). In the same vein, Lisa Cook has denounced in multiple interviews and journal articles that there are major hurdles for African American -and especially for female African Americans- who want to study economics or pursue an applied or academic career in the field (Cook & Opoku-Agyeman, 2019; Cook & Gerson, 2019).

In contrast, renowned economists such as Harald Uhling,1 who is currently co-editor of the Journal of Political Economy and Professor at the University of Chicago, have criticized the growing importance of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Larry Kudlow, who served as director of the White House National Economic Council, took a strong position on the debate, asserting that he "does not believe that systematic racism exists in the United States" (Casselman & Tanker-sley, 2020, para. 4). These declarations do not mention the economics profession explicitly, but are probably a good reflection of the way some economists disparage the debate about discrimination in the field. For example, in the final AEA Professional Climate Survey report, most of those surveyed considered that there are discrimination problems in economics, but a smaller group believed that the climate in the profession is good and unproblematic (Allgood et al., 2019). A few white and, interestingly, Asian economists voiced opposition to initiatives such as special scholarships and programmes made to incentivize minorities to pursue a career in economics: they consider that these efforts have negative consequences for other groups of students who want to be part of the field, as they cannot access these benefits because of their race (Allgood et al., 2019).

In this context, I analyse the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) to evaluate if the data allows inferring the existence of systematic discrimination against Hispanic and African American people at U.S. universities, and (particularly in economics departments). According to the Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession (CSMGEP), since the IPEDS is conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), data have revealed that the proportion of Hispanic and African American students within the U.S. postsecondary education system is below its relative weight in the total population (CSMGEP, 2019b). In this document, I show that this trend has continued and that it may indicate the persistence of social, cultural, and economic obstacles. Those obstacles probably hinder access to careers in economics or obstruct the link to labour markets associated with the economics discipline for non-white people (Goldsmith et al., 2007).

I am aware that there is a large amount of research about discrimination in economics in the U.S. concerning not only African Americans and Hispanics but also the situation for women and other underrepresented minorities. Those analyses go beyond the objective of this paper; nevertheless, I recognise they are very important, and the discussion would be incomplete without them. Hopefully, this investigation will be another small contribution to a universe of new analyses attempting to draw attention to the importance of inclusion and diversification into the economics profession.

However, an issue I do discuss is how the centralization of the discipline in the U.S. has led to some contempt for professionals trained outside the main educational centres in that country. Economics mostly appears as a standardized discipline with a clear centre in the U.S., which serves as a reference for practice, research, and methods for economists around the world. Many economics departments in regions such as Latin America use similar processes for job applications, giving tenure, or publishing an article as those followed by U.S. institutions. Consequently, it is probable that many of the obstacles to access the economics profession in Latin America are similar to those in the U.S.: minority groups in Latin America might be going through processes comparable to those described by African American and Hispanic students in the U.S. This might also indicate that more research on the topic is necessary if we were to understand the specificities of the experience and trajectories of minority economists in the Global South and how their professional development in the field may be dependent on factors including networks or nepotism.

I draw attention to the importance of using new approaches in the research about discrimination in economics in Latin America, which to my knowledge, are very scarce. Encouraging the study of this topic could open the door to further discussion in Latin American economics departments about underrepresentation of minorities and make the exchange of ideas between economists formed in the U.S. and in Latin America more feasible.

In the first part of this paper, I analyse the IPEDS data about the representation of African Americans and Hispanics in economics and provide some stylized facts. In the second section, I relate my findings to the existing literature and examine the consequences of the existence of racial discrimination in economics. In the third section, I discuss some of the advances that have been made in economics to address the problem and some of the models that try to explain why it exists. In the fourth section, I present some ways in which each member of the economics community could help to alleviate the underrepresentation of minorities in the field. In the fifth section, I relate some of the possible effects of this problem over the peripheral institutions that teach economics, such as universities in Latin America. Finally, I discuss why addressing underrepresentation and discrimination in economics is important and present some conclusions.

THE IPEDS DATA AND SOME STYLIZED FACTS

The change in the representation of Hispanic and African Americans within economics was assessed by the construction of an integrated database including information from 1995 to 2019, and the information was taken from the IPEDS (NCES, 2020), as carried out by CSMGEP until 2017 (CSMGEP, 2019a). All the degree-granting institutions participated in the survey,2 although students who were not permanent residents in the U.S. were excluded. Some data used for the comparative analysis is presented from 2003 onwards due to IPEDS availability. The categorization is based on the analysis of inscription forms in which each student can categorize himself or herself as "white, black or African origin, Indigenous Origin, Asian Origin, or some other race" and indicate if he or she is from a "Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin" (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019).

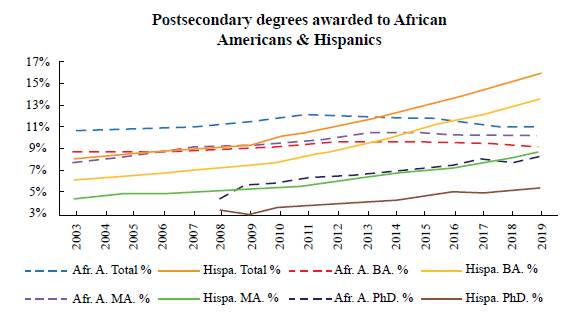

Figure 1 shows all the degrees awarded to Hispanics and African Americans according to IPEDS data between 2003 and 2019. Hispanics have significantly increased their representation in all higher education programmes since 2003, increasing from 8% to 15.24% in 2019. African Americans reached a peak number of graduates in 2012 with 12.14%, but since then their participation stalled and even decreased to 11.16% in 2019.

Source: Own elaboration with data taken from The IPEDS (NCES, 2020).

Figure 1 Degrees Awarded to African Americans and Hispanics in All Subjects Between 2003 and 2019

The proportion of African Americans and Hispanics within the U.S. population was estimated at 12.8%3 and 18.45%,4 respectively, in 2019 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). In contrast, the participation of these groups was 9.40% and 13.64% at undergraduate level. At master's level, the proportion was 10.38% for African Americans and 8.81% for Hispanics. For PhDs, the participation of both groups has been increasing, but it remains low, at 8.38% and 5.44%, respectively.

The participation of Hispanics in undergraduate degrees doubled between 2002 and 2019. However, their underrepresentation in graduate schools would indicate that -even though some of the barriers that limit their entry to higher education in the U.S. have gradually been mitigated- the changes are so recent that they are not significantly reflected at the masters and doctoral levels.

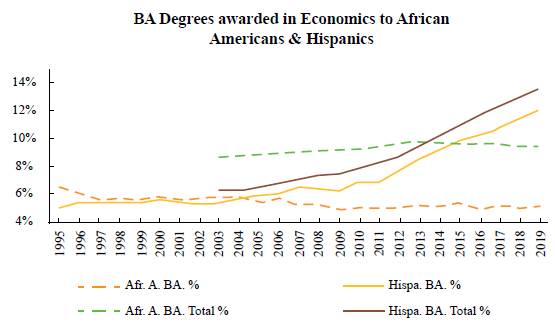

Figure 2 shows the dynamics of undergraduate degrees awarded to Hispanics and African Americans in economics and all subjects between 1995 and 2019. The participation of both groups in undergraduate degrees in economics is below the all-subjects proportion. Although Hispanics follow a very similar trend to that of the total and reached 11.53% in 2019, the outlook is concerning for African Americans. Their representation among economics graduates at the bachelor's level has fallen since 1995 and remained at around 5% since 2009. These facts may reflect the hardening of hurdles and obstacles they must face to aspire to a career in economics.

Source: Own elaboration with data taken from The IPEDS (NCES, 2020).

Figure 2 Degrees Awarded to African Americans and Hispanics in Economics BA Between 1995 and 2019

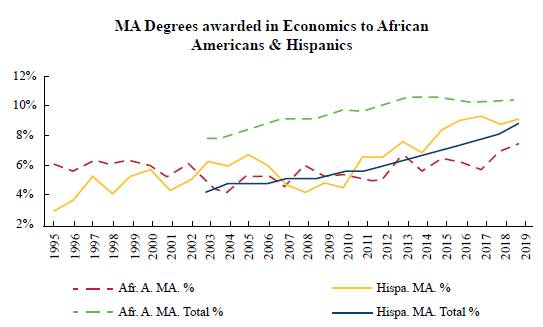

Figure 3 presents the historical proportion of African American and Hispanic master's graduates in economics and all subjects. At the master's level, the general participation of African Americans is higher, but there was a decline from 2012, reaching a low of 10.38% in 2019. Although their participation in economics master's programmes peaked at 7.09% in 2018, the behaviour of the variable has been erratic and does not seem to reflect a growing trend. In contrast, Hispanics reached a maximum participation of 8.81% in all masters, but the variable is growing steadily. Additionally, their participation in economics master's programs has been higher than for the average master's degree since 2011, but it is still well below their share of the U.S. population.

Source: Own elaboration with data taken from The IPEDS (NCES, 2020).

Figure 3 MA Degrees Awarded to African Americans and Hispanics in Economics Between 1995 and 2019

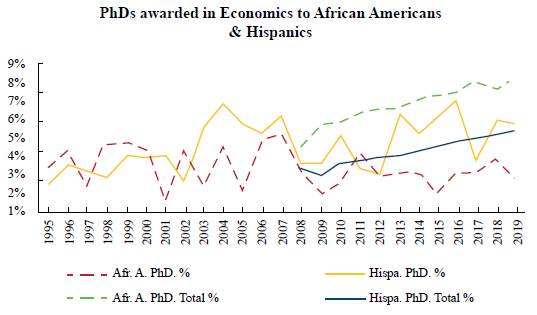

The total participation of African Americans and Hispanics in doctoral programmes has increased since 2002. However, as shown in figure 4, the representation of African Americans in economics Ph.D. programs was low and very volatile in the same period. For Hispanics, representation in economics Ph.D. programs has also been variable, but there has been a better performance when compared to the representation of African Americans. As I will address later in this paper, the low proportion of minorities in Ph.D. programmes could be attributed to two main factors. The first is the probable existence of obstacles that hinder access to higher levels of education for African Americans and Hispanics (Allgood et al., 2019). The second is the existence of a collective imaginary that makes minorities believe that a Ph.D. in economics will not significantly improve their employment perspectives in the field (Goldsmith et al., 2004).

Source: Own elaboration with data taken from The IPEDS (NCES, 2020).

Figure 4 PhDs Awarded to African Americans and Hispanics in Economics Between 1995 and 2019.

Table 1 shows the representation of African Americans and Hispanics in the departments of economics for the 2018-2019 academic year. In most cases, faculty members who identified themselves with any of these racial groups did not represent more than 5% of the total at a given degree level or type of association with the educational institution. The presence of Hispanic or African American professors in economics departments is far below their proportion in the U.S. population, which, in turn, makes it difficult to adequately study and address the specific problems that affect these communities. The AEA reports that "only 3% of the profession identifies as Black (...) and almost half (47%) of Black respondents reported experiences of discrimination in economics" (American Economic Association, 2020, par. 3), contrasted with 16% of Hispanics who report experiencing discrimination or unfair treatment.

Table 1 African American and Hispanic Professors in Economics Faculties for Academic Year 2018-2019

| Level | Full Prof. | Associate Prof. | Assistant Prof. | Other | Total Full Time | Total Part. Time |

| African American | ||||||

| BA. | 2.30% | 3.30% | 3.50% | 4.80% | 3.00% | 2.50% |

| MA. | 3.20% | 3.80% | 2.40% | 3.10% | 3.10% | 2.30% |

| PhD. | 1.70% | 2.40% | 1.80% | 4.90% | 2.00% | 4.10% |

| Total | 2.00% | 2.90% | 2.50% | 4.50% | 2.40% | 3.20% |

| Hispanic | ||||||

| BA. | 2.10% | 4.00% | 3.90% | 4.80% | 3.00% | 1.60% |

| MA. | 2.70% | 4.60% | 5.60% | 9.40% | 4.20% | 3.90% |

| PhD. | 4.80% | 7.30% | 7.40% | 3.70% | 6.20% | 1.40% |

| Total | 3.80% | 5.70% | 5.90% | 5.10% | 4.90% | 1.90% |

Source: Own elaboration with data taken from CSMGEP (2019).

EXCLUSION AND PSYCHOLOGICAL BARRIERS

It cannot be denied that the participation of African Americans and Hispanics in the economic discipline is greater than half a century ago, and even 20 years ago. Incentives to integrate these populations into the community have increased, and many institutions have become aware of the underrepresentation problem. For example, the AEA5 and the American Society of Hispanic Economists (ASHE)6 have implemented a series of courses such as The Summer Training Program, The Mentoring Program, and The Summer Fellows Program, which focus on encouraging minority representation in economics (CSMGEP, 2019b). The Summer Training Program is meant to prepare undergraduate students from underrepresented minorities for Ph.D. programmes in economics: it runs for about 7 to 8 weeks and undergraduates take classes in maths, microeconomic theory, econometrics, and writing research papers (American Economic Association, 2021). The Mentoring Program matches underrepresented minority graduate students with Ph.D. economists for one-on-one mentoring. The Economics Fellows Program places junior professors and graduate students in research communities of government organizations, and they are allowed to work on their own research projects (Bayer et al., 2020).

There are other important recent developments in this matter, as the establishment of the AEA's Code of Professional Conduct, Committee on Equity, Diversity, and Professional Conduct, Policy on Harassment and Discrimination, and Task Force on Best Practices, which signals an increase in the awareness of the problem in terms of obstacles on the demand side (Bayer et al., 2020). Besides, in April 2018, the AEA established a new standing Committee on Equity, Diversity, and Professional Conduct (CEDPC) (American Economic Association, 2018). The code states that the goal is to "create a professional environment with equal opportunity and fair treatment for all economists." CEDPC aims to implement initiatives to address the professional climate in economics, including those recommended in the final report of the AEA Professional Climate Survey. I agree with Bayer et al. (2020) that those steps alone are necessary and welcome, but they are not sufficient.

Discrimination against minorities persists in more subtle ways than it did in the past. However, it still has significant effects on the quality of life of minorities, their ability to exercise civil and political rights, and, consequently, their ability to pursue a career in economics. Hamilton (2017) found evidence that rhetoric emphasizing that "hard work, individual agency, and personal responsibility are enough to close the job gaps" (p. 5) has had a disheartening effect: the pressure on socially stigmatized groups to achieve their goals imposes physical and psychological costs on their health. "They are required to exert considerable energy on a daily basis to cope with conditions of high anxiety or uncertainty" (Hamilton, 2017, p. 14). In consequence, the individuals belonging to these groups tend to have worse health than an average white individual with the same income or degree of professional achievement, and it is probably even worse in severely hierarchical professions such as economics.

Many African Americans have done everything society has asked of them, but they have rarely reached the top of their careers' leading institutions. Goldsmith et al. (2007) explain that these populations sometimes change their job or field of preference to avoid the psychological discomfort produced by participating in hostile work and educational environments in which they feel discriminated against.

Exclusion can generate cognitive dissonances, which leads to internalizing the belief that they have negative or inferior characteristics, which are attributed to them from the dominant circles of society (Aronson et al., 1998). In economics, not only do minorities find it difficult to access the academic and work environments, but their classification as "different" individuals has induced many of them to change their aspirations, habits, and objectives (Allgood et al., 2019). Of the Hispanic, African American, and Native American respondents to the American Economic Association Climate Survey in 2018-2019, 28% reported having been discriminated against or treated unfairly based on ethnicity or race by someone in the field of economics (Allgood et al., 2019). Many others reported starting a career in economics, but then having dropped out, or said they were unsatisfied in their current position for the same reasons (Allgood et al., 2019).7

Research shows that "performance in academic contexts can be harmed by the awareness that one's behaviour might be viewed through the lens of racial stereotypes" (Steele & Aronson, 1995). For example, Allgood et al. (2019) found that among Hispanics there was a greater tendency to decide to not present an idea, view, or question at school or place of work (6% gap with respect to the other groups). Among African Americans, the tendency was not to attend a social event or take a particular job: "32% of Black respondents report not having applied for or taken a particular employment position to avoid harassment, discrimination, or unfair treatment, compared to 15% of non-Black respondents; 41% of Black respondents report not having attended social events, compared to 25% of non-Black respondents" (Allgood et al., 2019, p. 17).

Additionally, 26% of African American and 24% of Hispanic respondents reported having suffered personal experiences of unfair treatment in promotion decisions in academia compared to 15% of white respondents, and there was a frequent reference to elitism in economics: There is a sense that the NBER, the AEA, and the top journals are controlled by economists from the top institutions. There is evidence that the obstacles for Hispanics and African Americans to access and success in the economics discipline go beyond the institutional structure and have become embedded in the imagination not only of the discriminators but also in the minds of many of those who are discriminated against.

IS THE GLASS HALF EMPTY OR HALF FULL?

There are many encouraging facts concerning actions against racial discrimination in the U.S. Every year, more and more white young men and women support and are galvanized by racial equality movements such as BLM, e.g., in several historically "white cities", more posters were supporting the movement than there were African American residents (The Economist, 2020). Hispanics are making their way into the American workforce and academic field. The trend seems to indicate that the growth in their representation in the study of economics is proportional to their increasing share in the population. However, both groups are still underrepresented in all areas of the economics profession. The stagnation of the proportion of African American graduates in economics is worrying, given that their representation in the population is expected to continue growing and reach 13.4% in 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

As shown in section two, many public and private agents try to provide support to these groups that are discriminated against. However, more times than expected, these efforts end up re-victimizing them. Many programs and models have tended to focus on minority male youths' motivations and behaviours, rather than addressing the labour market conditions that they confront, which is consistent with the economic orthodoxy of market primacy in distribution and allocation (Aja et al., 2014). A common -well-founded- criticism of research on the economics of race is that it is largely based on trying to model the behaviour of minority communities, rather than describing structural racism as an explanation for differences in outcomes between racial and ethnic groups (Darity et al., 2015).

Most theories in economics about discrimination can be classified into two categories: statistical and taste-based discrimination models. In Becker's taste-based discrimination models, some individuals act as if they were willing to pay something or assume a non-monetary cost, either to be associated with a certain group of people rather than others or to avoid transactions with persons belonging to the group that is being discriminated against (Becker, 1971, p. 14). In statistical discrimination models, discrimination takes place because of the stereotypes based on group membership, which is a result of the lack of information to make decisions. In these models, economic agents attempt to assess certain abilities or characteristics of persons based on limited information (Phelps, 1972). In other words, employers, professors, editors, or student groups are supposed to try to predict the possible behaviour -or another unobservable characteristic- of a person using an observable signal as their race or skin colour (Arrow, 1971).

In the 1970s, many economists criticized Becker's model. Arrow signalled that perfect competition would drive discriminatory agents "out of the market", arguing that the model predicted the elimination of the phenomenon it was created to explain (Arrow, 1998). In Becker's 1957 taste-based discrimination model, if enough non-discriminating employers or jobs exist then discrimination would not persist in the job market and discriminated workers would not work for discriminating employers, so there would be segregation (Autor, 2003, p. 4). Moreover, other extensions of this model show that customer discrimination could persist in equilibrium because customers could be willing to pay higher prices for goods that would allow them not to interact with those who they discriminate against (Autor, 2003, p. 6). This is a troublesome result that shows discrimination and segregation are compatible with competitive equilibria or that, contrary to evidence, market competition would solve the problem by itself. In consequence, statistical discrimination models became the new standard in economics literature about discrimination (Guryan & Charles, 2013).

Nevertheless, those models struggle to explain several real situations. For example, "the added credentials should lead to a larger update for African-Americans and hence greater returns to skills for that group" (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004, p. 10-10), which has been largely contradicted by several empirical experiments (Bertrand et al., 2005). A second type of statistical discrimination model indicates that the discriminators believe that the same observable characteristic is more precise for white men than for African Americans or other minorities (Guryan & Charles, 2013), and consequently, these populations receive fewer attributions - in multiple dimensions- in exchange for observable skills because people pay less importance to those skills (Guryan & Charles, 2013).

In 1998, Arrow claimed that there is enough evidence that marked-based theories are inadequate to explain the motivations and effects of racial discrimination on the economic system and proposed paying more attention to models that include social segregation through network referrals. In this case, there is no cost of discrimination for the discriminator; instead, they receive social rewards (Arrow, 1998). In an attempt to address this liability, Akerlof and Kranton (2000) incorporated identity into a model of behaviour and tried to identify how individuals' identities can influence economic outcomes. They argue that the focus on identity is prominent in psychology and that economists should consider it as an argument in utility functions. Concerning Professional and Graduate Schools, they claim that programmes are meant to mould students' behaviour through a change in identity, which is revealed when "a title is added to a graduate's name, suggesting the change in person" (Akerlof & Kranton, 2000). The researchers explain that the sense of self is associated with specific social categories and the idea of how these categories should behave, so the identity affects the payoffs from each person's actions and the actions of others (Akerlof & Kranton, 2000). As a result, behavioural prescriptions can be altered, affecting preferences based on identity relating to multiple aspects of each person's life, including their desire to enter a career in economics or the way they treat their fellow economists who belong to a minority.

Finally, another alternative is the Implicit Discrimination model, which is currently largely accepted and has been studied over the last two decades. Theory on implicit discrimination signals that the differential treatment of some minorities by the dominant groups -or even themselves- is not always intentional and can be outside the range of the things they perceive. That is, they make "unconscious mental associations between a target and a given attribute" (Bertrand et al., 2005).

These theoretical approaches in mainstream economics have allowed discrimination and segregation to be studied and better understood, especially in the job market. However, to my knowledge, little has been done to use these models to approach discriminatory practices in economics, including those reported in the AEA Professional Climate Survey (Allgood et al., 2019). It is as if economists focus on behaviours and phenomena they do not seem to extend to their own practices and scholarly community. Although tackling discriminatory practices within the profession has received attention, especially in the U.S., this is still an understudied dimension of the economics profession. Evidence has been gathered and statements have been issued. The AEA -as one of the main governing bodies of the profession worldwide- has expressed concern and the will to avoid and condemn discriminatory practices, but this has not been followed by a systematic study on taste-based or statistical discrimination in economics and the effects this type of behaviour may have on the interaction between economists themselves.

Explicitly discriminatory behaviour may occur less than in the past, but it does not mean it no longer exists (Bayer & Rouse, 2016). Nevertheless, researchers have studied implicit bias since the mid-90s because it has been useful to identify ways in which we can address the problem, despite not providing an exact quantification of the magnitude and effects of discrimination. Research suggests that interactions at all stages of the academic pipeline are influenced by implicit bias, including admission, promotion, and other formal decisions (Bayer & Rouse, 2016). The same operates for informal interactions, such as responding to questions and ideas of colleagues or advising students (Bayer & Rouse, 2016). For example, Milkman et al. (2015) conducted a study across 259 U.S. universities in which 6500 professors in 89 disciplines received an email from a fictional student, asking for a 10-minute meeting to talk about research opportunities before applying to a doctoral program. "The student's name was randomly assigned to signal gender and race" (Bayer & Rouse, 2016), but the messages were identical. In almost all disciplines, faculty ignored the emails from minorities and women at higher rates than requests from white males, with large statistically significant discriminatory gaps. In the social sciences, which pools economics with 18 other disciplines, 75% of white males received an answer, compared with 68% of women and minorities.

Implicit and explicit bias models have been a useful tool in trying to explain many of the "hurts" minority students of economics have denounced during the enrolment, pre-application, or selection processes (Bayer et al., 2020). In the AEA Climate Survey, many respondents expressed feeling unheard in seminars, classes, and conversations or said their scholarship was disesteemed in most of the important journals (Allgood et al., 2019). One of the respondents wrote: "The economics profession is brutal. Colleagues and students can be disrespectful, have implicit biases, and [do] not understand the stress that being a minority economist entails. My senior colleagues also didn't help me with my tenure process, and they didn't help me when stressful situations arose" (Bayer et al., 2020, p. 199). The results of the same survey indicate that African American responders and women -especially African American women- are more likely to have experienced discrimination within economics and to have taken actions such as leaving a job or job opportunity to avoid unjust treatment (Bayer et al., 2020).

Allgood et al. (2019) describe economics as endogenous to whoever is practicing it: "the papers that are published in the most prominent journals, the individuals who are tenured at the most prestigious institutions, and the policy options that are developed and implemented all plausibly depend on the identity and characteristics of those who are driving each of these actions" (Bayer & Wilcox, 2019, p. 307). In consequence, the question should not be if there is still racism and discrimination but how we can help to address this problem and make it visible to find effective solutions.

HOW CAN WE HELP?

Moved by concern about the low diversity entailing further homogenization of the field (Fourcade et al., 2015), Bayer et al. (2020) conducted 75 surveys and interviews with Black, Hispanic, and Native American economists to find out "what helps and hurts minority group members to succeed in economics" (Bayer et al. 2020, p. 194). Based on these testimonies, the authors analysed a set of recommendations that do not seem difficult to follow but that would need institutional incentives to be largely implemented. The interviewees' recommendations included making bias and hostile climates visible and unacceptable and providing more information and mentoring for minority groups, as well as establishing more effective communication channels to make their voices heard.

These recommendations tackle the three main hurdles mentioned by respondents in the AEA Climate Survey to their careers in economics: the lack of mentoring, the lack of adequate information, and the existence of implicit bias. Besides, there were recurrent allusions to elitism, institutional inaction about discrimination, a lack of listening by colleagues or professors, and the field's lack of openness to new questions and methods (Allgood et al., 2019).

Bayer et al. (2020) propose focusing efforts on three main areas to increase the representation of minorities in economics: inform, mentor, and welcome. Informing students about programmes that help them transit from a BA to an economics Ph.D. could have a big impact, as noted by one individual surveyed: "I did not know this A[E]A [Summer] Program existed at all. No one ever mentioned its existence to me... [H]aving this be known to all economists would be very beneficial so that they can then just tell their students" (Allgood et al., 2019). In an experiment involving 2710 students from nine U.S. colleges, Bayer et al. (2019) showed that just emailing information about a diverse array of topics and researchers within economics to new women and minority college students increases their likelihood of completing an economics course in the first semester by nearly 20% of the base rate.

Mentoring can also be very effective, e.g., Lusher et al. (2018) find that the academic performance of undergraduates is improved when they are matched with the same-race graduate student teaching assistants in economics courses, or they are continuously informed about the offices or faculty members they can turn to for advice. Finally, some experiments showed that interventions can make a career in economics more welcoming for minorities by altering implicit attitudes. Devine et al. (2012) found that, after a 4-month course to raise awareness of the existence and effects of implicit bias -and an array of proven strategies to reduce bias-, the students in the treated group changed their scores on implicit bias tests about African American-White associations in a significant and enduring way compared to those in the control group.

THE DISCIPLINE'S HIERARCHIZATION AND ITS IMPORTANCE ON "PERIFERICAL" INSTITUTIONS

As a student of economics at the National University of Colombia, I was impressed about how much I identified with some statements made by some of those surveyed in the AEA Climate Survey when they denounced the lack of information in their courses about the specifics of where economists work, or when they complained about the lack of real examples on the relationship between economics and public policy work in and out of government (Bayer et al., 2020). In several conversations with other students from my university and other institutions such as the University of Los Andes, I have identified that many of us would like faculty members to take more time to share information about economic research and the different things economists do outside the classroom. Additionally, it is worrying that many of us take for granted that professional development in the field is strongly dependent on networks or nepotism, and that the chances of success are greatly diminished if you are not part of one of these networks -within which decisions are made on the curriculum of economics programs, on the objectives of funded investigations, and on the macroeconomic policies of our countries-. Those networks are also very likely to have a large influence on prestigious "think tanks" that advise conglomerates and companies in the private sector.

It is clear that my impressions may not be a representative description of what is happening in the field of economics in Colombia or in any other Latin American country, but it might be a signal that Colombian and Latin American economics students might be going through comparable processes to those described by African American and Hispanic students in the U.S. This might also indicate that more research on the topic is necessary if we want to understand the specificities of the experience and trajectories of minority economists in the region. To the best of my knowledge, there is not much research on racism, elitism, and exclusion in economics in Latin America, and there is not much easily accessible data on the representation of minority groups -such as Indigenous or Afro-descendants- in the field. However, many of the hindrances to access the economics profession in Latin America are probably similar to the ones in many U.S. institutions, given that our top educational institutions -especially in economics- tend or seem to follow the teaching methods, theoretical approaches, and applied techniques that are used in the U.S. Economics appears as a mostly standardized discipline with a clear centre in the U.S. acting as an attraction pole for practice, research, and methods for economists worldwide. Many economics departments in Latin America use similar processes to apply for a job, gain tenure, or publish an article as those followed in U.S. institutions.

This centralization of the discipline is also connected with the last problem I would like to address. The rise of U.S. as the centre of the profession has led to a certain contempt for professionals trained outside the main educational centres in that country: "As an economist from a Latin American country, we are required to have more years of education to apply for a Ph.D. (most students who apply have a MA in economics). So Latin American students apply to a U.S. program by their mid/late 20s" (Bayer et al., 2020, p. 204). In general, there is a feeling that those who obtained their degree, or work, outside the U.S. "are not given the appropriate level of respect" (Allgood et al., 2019, p. 99).

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO ADDRESS SUB-REPRESENTATION OF MINORITIES IN ECONOMICS?

The work published by economists has paid little attention to racism and discrimination, "just 1 percent of economics articles mention the phenomenon, while other social science disciplines discuss it at two to five times that rate" (Bayer & Rouse, 2016). The lack of more systematic research on racism and discriminatory practices within the discipline might hinder tackling this issue in a more systematic and informed way, which obstructs the formation of a more pluralistic and diverse community.

The lack of diversity in economics can lead to a myopic view of multiple economic problems and many of their potential solutions, especially if they affect minority populations to a greater extent. Following Bayer et al. (2020) it is possible to state that economics is losing out on diverse perspectives and that the capacities and talent of many marginalized economists are being employed inefficiently because many of them alter their research, participation, or workplaces to avoid unfair treatment, which endangers our capacity to build and produce relevant and robust knowledge. In an experiment with 216 business students, Phillips et al. (2006) showed that racially diverse groups perform better than other groups in addressing and solving complex problems because more homogeneous groups spend less time on the activity as they perceive their opinions as less different. Levine et al. (2014) found that traders in heterogenous marketplaces are less likely to give undue confidence to others' decisions, leading to fewer price bubbles. Freeman and Huang (2015) found that among 2.5 million papers written between 1985 and 2008, the ones that had been written by more diverse teams had more citations and impact than those with authors from the same ethnic group.

Government policies are clearly influenced by the experiences and identities of those who study economics, and as a result, when these experiences are representative, more people are benefited (Bayer & Wilcox, 2019). Policy suggestions and opinions are not equal across different groups of economists, as May et al. (2014) found in a survey of AEA doctoral members. Then, the approaches and views in economics are likely to be biased by the relative absence of minority and female economists, which affects policies and decisions from institutions such as the central banks or Finance ministries.

CONCLUSIONS

Although there is an increase in efforts by certain institutions, such as the AEA and the ASHE, to provide programmes and scholarships that encourage the representation of ethnic and racial minorities in the economic discipline, there are still socioeconomic, political, and cultural barriers that discourage access to studies in economics for African Americans and Hispanics. These barriers are prevalent and usually manifest themselves after individuals have started their training in the discipline. This situation causes dropouts from academic programmes or truncates the educational and employment achievement of graduates.

The IPEDS data reveal that the representation of Hispanics in economics has grown during the 21st century; however, this is still lower than their percentage of the total U.S. population. The landscape for African Americans is more concerning, their participation in economics has notably stalled and even declined. This could worsen their involvement in the identification of socioeconomic problems and in the formulation of policies and solutions that consider the needs of stigmatized minorities. There are many studies and papers about the social obstacles that have affected the participation of Hispanics and African Americans in economics, the labour market, and the educational environment in general. These kinds of research should not only continue to be encouraged but should be used to propose new policies that help give a voice and agency to those who have been systematically ignored.

Faculty members, researchers, and heads of important institutions in economics -such as academic journals, multilateral financial agencies, and central banks- should work actively to inform, mentor, and welcome minorities in the field, given that the whole society can benefit from their participation. Increasing inclusion in our discipline is possible, and there is evidence that the patterns in the choice of career from minorities are not only the result of students' preferences. That is the reason to develop programmes and strategies to change institutional practices that alienate minorities from the economics discipline. The identity of participants in economic policy affects the problems seen as urgent and the ideas and solutions that are believed to be most promising.

Hopefully, we are on the way to changing the perception that economists are competing in a pit with each other, in which, in the end, only the best students or professors from the best universities "take it all". Instead, we should start to support each other, to call out sexism, racism, and any kind of harassment. We should seek to improve the environment of the profession -going beyond the appearances, rankings, and grades- to develop studies, proposals, and economic policies that aim to improve the well-being of all members of our communities, which is probably the main reason we choose to study this field.