INTRODUCTION

The debate over the homogeneity or heterogeneity of savings is closely linked to the debate on the nature of capital, which first began with Böhm-Bawerk and Clark (Cohen, 2008) and was later developed by Knight and Hayek (Cohen, 2003). Following these contentions, the consideration of capital has followed one of two opposing views: the first defined capital as a homogenous and self-reproducing monetary fund and the second as a structure or pattern of combinations of heterogeneous and consumable goods.

Years later, Joan Robinson (1953) started the so-called "Cambridge Controversy on Capital Theory" (Cohen & Harcourt, 2003) with the publication of a provocative paper attacking one of the core assumptions of mainstream, as well as Austrian, economic theory of capital and interest: the inverse relationship between savings and interest rates. Besides the implications for the general equilibrium approach and neoclassical growth theory, this proposition represented a direct attack on the foundations of the Austrian school of economics' conception of secular sustainable growth. After at least two decades of bitter debate, the controversy came to an end with an "implicit" surrender of the neoclassical economists and the isolation of the Austrians.

This paper follows the lead of Bagus and Howden (2010) regarding the implementation of a disaggregated monetary savings framework by the Austrian School of Economics. The main ideas behind growth constraints caused by savings' embodiments were established in Hayek (1937) 1, stressing the complexity of capital good caused by the complementarity relationships between the supply of saved capital goods and the investment demand for capital goods. A similar problem arises when savings are treated as homogeneous within the credit markets, as in the mac-roeconomic identity S = I.

This paper contributes to the existing literature in two main aspects. First, defining and including the subset of cash-built savings based on the desired availability. Secondly, with respect to the focus presented regarding how an increase in aggregated savings can generate different growth paths, this paper is a first step toward enriching the study of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory through the capital-based macroeconomic framework

However, instead of basing the analysis on the time structure of savings, this paper focuses on the market signals of the pure/genuine savings and cash-built savings. To present the results and their implications a 100% reserve banking system able to mismatch savings maturities is assumed to showcase the initial equilibrium and sustainable growth in capital-based macroeconomics,

SAVINGS AND ITS EMBODIMENTS. DEFINITIONS AND SOME PARTICULAR CASES

The literature on the conceptual framework of savings can be divided into two radically opposed views, despite the taxonomy proposed by classical schools of economic thought: a) authors identifying saving as a precondition for investment, and b) those defining saving as a residual of consumption decisions.

The first of these two positions is partially shared by both Neoclassical-synthesis and Austrian economists, given that both begin by stating that saving is a necessary pre-condition for investment (and thus the capitalisation of the economy). Solow (1956, p. 66) illustrates the formal definition of saving proposed by the Neoclassical-synthesis school and its connection to investment: "Part of each instant's output is consumed and the rest is saved and invested. The fraction of output saved is a constant s, so that the rate of saving is s Y(t)..."; However, Modigliani's (1944, p. 49) definition stresses the roles of time and the individual decision to save:

In his endeavor to reach the highest level of satisfaction he is confronted with two sets of decisions: (a) he must decide what part of his income he will spend on consumption and what part he will save, (b) he must determine how to dispose of his assets.

In the tradition of the Austrian School of Economics, authors such as Rothbard (1962) or Huerta de Soto (1998) illustrate the connection between savings, capital structure and time by means of a Robinson Crusoe example2:

He must restrict his consumption [...] and transfer his labour for that period from producing immediately satisfying consumers' goods into the production of capital goods, which will prove their usefulness only in the future. The restriction of consumption is called saving, and the transfer of labour and land to the formation of capital goods is called investment. (Rothbard, 1962, p. 42)

The second of these positions is typically defended by the Keynesian authors. According to John Maynard Keynes, "[...] saving means a surplus of income on consumption expenditure" (Keynes, 1936, p. 46). This definition considers saving as a sub-product of consumption planning, i.e., for a given income level, agents consume what they want and, by definition, savings would be overrun. This implies that there is no explicit motive for saving because there is no individual process to determine the level of expenditure on saving. This position is based on two different points. Firstly, Keynes elevates the role of consumption, or rather expenditure, to the foremost position in economic analysis and, secondly, his analysis assumes a static perspective rather than a more realistic dynamic one.

As the working definition of saving used in this paper: "People do not just save (S); they save-up-for-something (SUFS). Their abstaining from present consumption serves a purpose; saving implies the intent to consume later" (Garrison, 2001, p. 40). This definition highlights the two most important features of the concept: the existence of a clear goal and the existence of a determined time duration in saving.

To explain the process by which the available stock of savings in each society varies. Huerta de Soto provides an illustrative explanation on how to verify an increase in savings (Huerta de Soto, 1998, pp. 313-315):

An increase in the rate of reinvestment of firms' profits,

A decrease in consumption by the owners of the original means of production,

The allocation of a part of income (by both the owners of the original means of production and capitalists) to production-oriented loans.

Following Garrison's definition of saving and its connection with investment, the decision of saving can be conceived as an individual's means to achieve their goals. Defining the goals pursued by the individual in terms of their future access to a given quantity of consumer goods, it is possible to analyse the various conceptions of this type of saving (See Table 1).

Table 1 Types of saving, by individual's goals and economic phenomena

| Maintain future consumption at present levels | Increase future consumption in comparison to present levels | |

| Stability of the monetary unit's purchasing power | - Saving cash. - Saving by purchasing assets that are perceived as low-risk | - Saving by purchasing assets whose expected returns allow for increases in future consumption. |

| Inflation/Deflation | - Saving by purchasing assets whose expected return compensates any change in the monetary unit's purchasing power | - Saving by purchasing assets whose expected return increases future consumption despite changes in a monetary unit's purchasing power. |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Cash-Built savings

The recent debate between Professors Bagus and P tru i has refocused attention on the role of cash-built savings, or money demand, in the Austrian school of economics framework. Comparing Keynesian and Austrian3 theory on the connection between cash-built savings4 and money demand might help understand the particularities of cash-built savings.

Liquidity preference in the Keynesian theory

In the General Theory (Keynes 1936 pp. 125-133), Keynes outlines his considerations with regard to the fundamental psychological motives that determined an economy's money demand. The first of these is the transaction-motive (income-motive for families and business-motive for firms), the second is the precautionary-motive and the third is the speculative-motive. The transaction-motive is given by the amount of time that separates an agent's receipt of income and its disbursements. The precautionary-motive arises from an agents' need to settle possible contingencies. The speculation-motive depends on the changes in expectations regarding the value of assets.

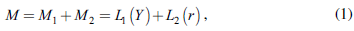

Following Keynes, the analysis of money demand should begin with the function

where M 1 contains all money, demand derived from the transaction- and precautionary-motives. The functional form of this first type of money demand, L 1 (Y ) = Y / V, depends on the economy's total output (Y) and total volume of transactions (V). M 2 is the money demand which is related to the speculative-motive and is given by the function L 2 (r) = f (r e ),where r e is the expected interest rate.

The Austrian perspective on money demand

Murray Rothbard's view of money demand adds a new axis to the traditional analysis of money motives, extending it to include dynamic aspects. Thus, he segments the analysis into that of pre-income demand (or exchange demand) and post-income demand (or reservation demand) versus that of total money demand and its stock.

Pre-income demand (Rothbard, 1962, pp. 367-452) is the made up of the suppliers' demand to exchange their goods and services for cash and is characterised as being, on the aggregate, decreasing in the purchasing power of a given monetary unit. Post-income demand (Rothbard, 1962, pp. 755-874) is the result of the discretionary use of income and is assumed to be decreasing in the monetary unit's purchasing power. Following this characterisation, variations in the available stock of money (which provoke changes in its purchasing power) cause opposite variations in its demand, as with any other good.

Cash-built savings can be a subset of savings that has a specific goal: using the accumulated purchasing power without limiting, or losing, the capacity to use these means of payment in the period between receiving income and consumption5. Accepting the early Keynesian categorisation and dividing money demand into precautionary, transaction and speculation motives, it is possible to integrate various subtleties into this analysis:

Precautionary saving. Relates money demand to the precautionary motive with the subjective cost category, which is given by the existence of uncertainty.

Transaction motive. It depends on the amount of time that must pass in between an individual's actions of collecting income and spending it, as well as the total volume of said transactions.

Speculative motive. This motive is tied to the subjective categories of profits and losses and is explained by the agent's expectations on asset price fluctuations.

In other terms6, the money demand or cash savings function can be expressed as

where aggregate money demand is defined to be a function of uncertainty (σ), expected inflation (π e)and the expected rate of return on investments and assets (re). While the first two are directly related to money demand (an increase in either implies an increase in demand), the third is inversely related.

Before concluding this subsection, it is necessary to briefly address the role of uncertainty in this model. Although its positive relation to money demand has been established, it is possible to make the mistake of using uncertainty as a sort of "catch-all" tool to further the model's analysis. To respond to this, uncertainty is composed of four specific components:

Permanent uncertainty. Since the future is not predetermined, all human action is subject to a certain degree of uncertainty.

Economic uncertainty. This concept should be understood as the uncertainty associated with an agent's sources of income, the volume of said income and its temporal distribution.

Regime uncertainty7. This subset expresses the uncertainty that surrounds the political and administrative organisation of a territory.

Legislative uncertainty8. Simply stated, this type exists because of the lack of legal certainty.

Hoarding and forced savings

Hoarding, as defined in the General Theory, is a type of restriction on consumption and accumulation of monetary units used to describe the extreme case of Keynesian liquidity preference theory (Keynes, 1936, pp. 110-111).

The fact that a rise in saving, understood in terms of Keynesian hoarding, leads to under-consumption is intimately tied to the theory of the circular flow of income and the analysis of the economy from a static point of view. Considering the macroeconomic identities9:

implies that any restriction on consumption, while not fully compensated by investment10, would reduce both output and income. This leads to the "Keynesian paradox of thrift": an increase in saving has the effect of reducing the aggregate level of available income. Without a detailed critique of the concept11, the inclusion of time into the analysis radically changes its outcome.

Considering the restrictions in terms of intertemporal consumption12 and introducing the proposed definition of saving, the desire to accumulate present-day purchasing power is fundamentally connected to being able to exercise this power in the future. Accepting the mechanics of the system of equations stated above (3), future available income implies higher future output. Therefore, by framing this process within a dynamic maximisation of income and output scope, the implications of the Keynesian under-consumption framework can be avoided.

Forced saving

As opposed to voluntary or true saving, forced saving would be an imposed reduction in an individual's desired consumption. The involuntary reduction in consumption can have many causes (Huerta de Soto 1998, pp. 409-413), which can be summarised in two broad categories: those induced by distortions in the productive process, and those induced by inflationary processes. Although both appear during expansionary credit processes, their nature differs, as does the process through which they develop.

In the first case, the process of credit expansion distorts a firm's productive structures and pushes it toward the production of future goods. However, consumers' time-preferences do not change, and the situation devolves into a tug-of-war over available resources between those industries closest to consumers and those furthest away. Therefore, the gap in time between the consumers' time-preferences and a firm's productive structure constrains individual consumption by limiting their choice of goods.

The second case is caused by the Cantillon effect that is associated with processes of credit expansion. The first agents to receive the newly created money face a price system which has yet to feel the effects of the expansion and, by purchasing goods and services with this new money, their increased demand begins to push prices upwards. As the newly created means of payments move away from the credit expansion's origin, in both space and time, its purchasing power begins to decrease. The result is that the last consumers to receive the credit expansion's "benefits" will witness a fall in their real income, which in turn forces them to reduce their consumption.

THE DIFFERENTIAL MARKET SIGNALS OF SAVINGS. RETHINKING THE LOANABLE FUNDS MARKET

Having defined saving, it's time to analyse the market signals generated by variations in an economy's rate of saving. When agents modify their time preference rate, they are changing the relative price of present and future goods. This modification, which manifests itself in various ways13, sends a signal to producers indicating that the existing productive structure does not satisfy current consumer preferences.

The manifestation of this lack of coordination between supply and demand is caused by the consumer giving greater value to future goods in detriment of present ones. Resolving this situation requires entrepreneurs to properly assess the quantity and quality of goods demanded by society.

However, this signal may not be complete, so for now it will be considered a partial signal. This raises the following questions: How can firms know what is causing the excess supply? Is it caused by the present supply of goods not satisfying consumer preferences? Or could it be a sign of a future increase in demand?

If the cause is the first of these two possibilities, a sufficient solution would be to redirect the firm's productive structure towards fulfiling consumer needs. However, if increased future demand is the cause, then the firm must become more capital-intensive, as this will allow it to fully supply consumers.

In accord with Garrison (2001, pp. 36-40), the supply of loanable funds, whether it be by the owners of the original means of production or by entrepreneurs, provides clarity to the framework within which firms choose their actions. Therefore, any variation in the amount of loanable funds works as a reinforced signal since these monetary savings are "that part of total income not spent on consumer goods but put to work instead earning interest (or dividends)" (Garrison, 2001, p. 36).

This concept allows the distinction between the two possible causes of excess supply in the example presented earlier. Should there be a variation in the amount of savings accompanied by a simultaneous variation in the amount of loanable funds in the same direction, the signal would be complete. Considering this reinforced signal, firms would begin to redirect their efforts towards more productive projects with longer maturities. On the contrary, if the variation in savings were not followed by a variation in loanable funds, a partial signal is given to the market and firms would not modify their productive processes. This analysis should also consider the production of goods and services while simultaneously including a dynamic conception of the saving process. An increase in savings does not only lead to a fall in output caused by the so-called derived-demand effect, but, if there is an equal increase in loanable funds supply, it is also followed by a time-discount effect improving the expected yield of new investments.

Once established the division between cash-built savings and loanable funds, the dynamics within the credit market need to be studied. First, the credit market needs to be compartmentalised according to its time-structure, dividing it between short- and longer-term markets14. This division also allows to analyse the different effects of cash-built savings and other monetary savings embodiments.

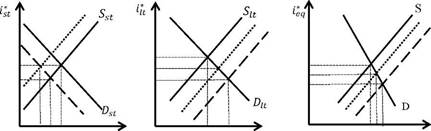

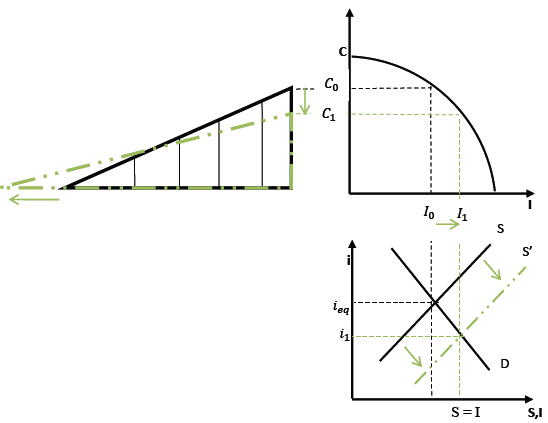

In static terms, an increase in money demand implies a contraction of the supply of loanable funds and a decrease in their demand in the short-term market. As the availability of an agent's liquidity begins to rise, their demand for short-term credit will tend to fall15. On the contrary, the long-term credit market will suffer the opposite effect: as the desired investment's term rises, there will be fewer incentives to finance it with cash balances. This explains why the reduced supply of loanable funds is not accompanied by an equal decrease in demand. In general, the share of long-term credit in aggregate credit will grow16. Figure 1 shows the aforementioned effect.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 1 The effect of an increase of money demand on disaggregated credit markets

To study the dynamics of a disaggregated credit market under a 100% reserve banking fystem, lei us analyse the case of an increase in pari pasu savings and an increase in liquidity preference, showing some complexities that may arise. A decreafe in the average intereft rates still can be expected, butthe short-teim credit market would experience a greaier decreafe than the longer-term market. This imbalance between market segments drivesthe banking system to exchange the credit supply from short-term to longer-term credit markets to aximize the expected value of Shieir balances.

This arbitrage by banks (Bagus & Howden, 2010) will push to close the gap between maturity segments, lowering interest rates for longer-term loans while raisin-* them foe short-term loan markets.

REASSESSING GARRISON'S ANALYSIS

This study began under the assumption that savings, in analytical terms, were composed of cash-built savings and loanable funds. Given the definitions presented so far, considering savings to be the part of the available income that agents explicitly decide not to use for present consumption, the connections and differences between both categories can be drafted.

Loanable funds are trie fraction of savings which agents willingly decide not to use during a certain period, so that in the future fhey may have a greater quantity (or ereater quality) of goods. Cashbuitt saving* shares the goal of satisfying future demand, but in this case the Serm is not defined with the samelevel of precision17 or the agent is unwilling to relinquish Iiis right to use these funds18. Although Garrison recognises the existence of cash balances that are not directly transformed into loanable funds (Garrison, 2001, p. 37), he limits his analysis to the study of liquidity preferences and static money itemand.

Implications for the model in its initial equilibrium

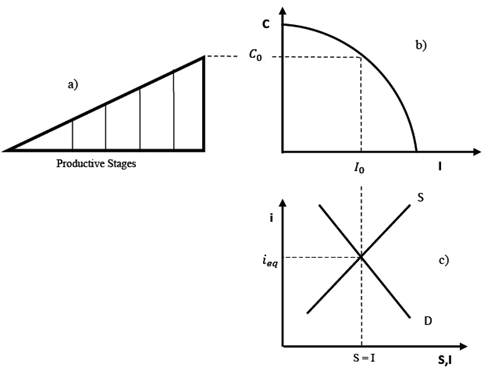

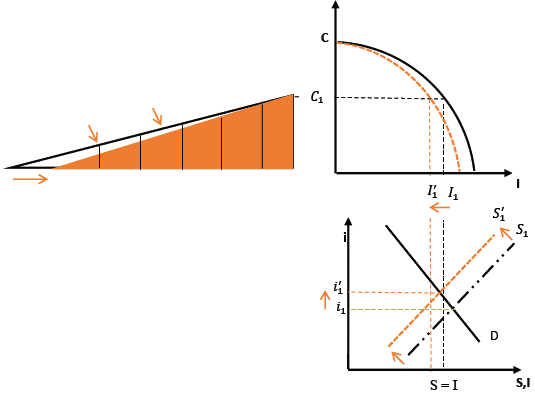

Figure 3 shows the graphical foundation of Garrison's analysis and presents an initial situation in which, gieen agents' time-preference, there is a productif structure ta) that is capable of satisfying present and future demand (represented as a possibility production frontier b)) and the market for loanable funds is in equilibrium at the natural interest rate (c).

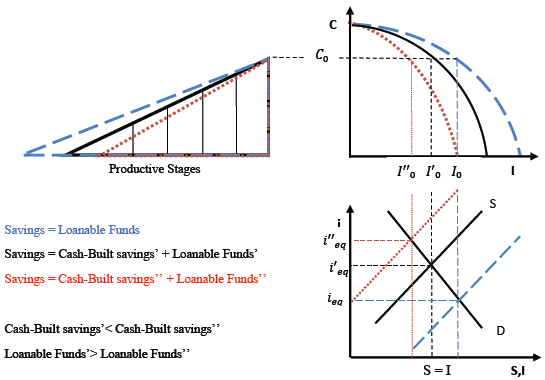

Despite referring to the loanable funds market and the interest rate in general terms, thisanalysis highlights the differential effect created by introducing money demand asanexus between short- and longer- term credit .Inthecircular flow of income frame-work, aggregate loanable lunds and savings would always be equal,following the dashrdline shown in figure 4. This absrract equivalence is urually implied in neoclassical models that assum e a perfect con-elation between the economy's savings rate19.

The solid lines in figure 4 show a much more descriptive case where savings are made up of money demand andloanable funds, following the hypothesis laid out sn this paper. It shows how the production-possibility frontier pivots around consumption because both supply and demand for present goods remain unchanged. This leads to the economy having fewer investment possibilities, hence the contraction in figure 4. This effect is also reflected in the market for loanable funds: if agents are unwilling to lose access to a given portion of a fixed stock of savings, an increase in the demand for loanable funds will cause the economy's natural interest rate to rise. The higher interest rate, which represents agents' new time preferences, will lead to a capital structure with fewer stages.

Implications for sustainable growth

ln trie capital-based macroeconomics iramework there are three possiblg sources of sustainable growth: i) cdvances in technology; ii) increases in available resourœs; and iii) changes in intertemporal preferences Given the aim of this paper, the focus will be on the scenario of changing intertemporal preferences to show the impact of cash-built savings on the growth pattern.

A change in social lime preferences that trans latef in-o cons umerf becoming thriftier will drive an increase in savings and a decrease in the demand for final goods. Thvs change in consumer behaviour willpush down the preces of final goods, triggering three microeconomic effects (Huerta de Soto, 1998, pp. 317-332):

1st. The disparity in profits between the different production stages. Firms closer to final consumers will begin to observe the effects of falling sales, reducing their profitability relative to firms located higher up on the supply chain.

2nd. The decrea f e in the mtenst rate on the market price of capital goods. The increase in savings, caeteris paribus, drives a reduction in the market interest rate. Given that capital goods are priced in terms of the discounted value of their cash flows, a decrease in interest rates increases the present market value of capital goods.

3rd. The Ricardo effect. The decrease in the prices of final goods causes a rise in real wages, which makes less labour-intensive productive processes relatively cheaper.

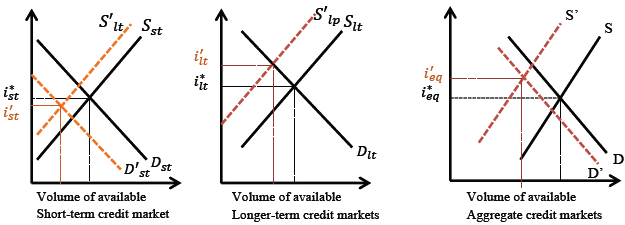

The combination of these three effects will lead to a new and more capital-intensive productive structure such as the one shown in figure 5.

As in the initial equilibrium presented earlier, savings in the forni ofcash balances noticeably reduces the impact of an increase in saving's in loanable fund0 markets, which translates into a smaller reduction in the interest rates. The outcome is a lower yield for investments in capitel goods. This consequence was identified by Pätruti (2016) as a decrease in the potential growth rate.

Assuming that this change in time preference is caused by one of the factors with a positive impact; on money demand (uncertainty or expected inflation). This can change the composition of saving s by increasing cash-build savings instead of other savings embodiments. Two important forces operate against the conclusion that an increase in savings will lead to a more lengthened and sustainable productive structure:

I. An incomplete signal market produced by a smaller reduction in interest rates following the decrease in demand for consumer goods. The allocation of new savings in cash balances makes it more difficult for entrepreneurs to identify whether the reduction in consumption implies greater future demand or the need to redirect their present production lines to other consumer goods. As a result, the production structure should start to contract.

II. The mismatching in the time structure of credit markets makes the new production structure more fragile. As shown in the analysis of a segmented credit market, an increase in cash-built savings reduces short-term interest rates, lowering trie profitability of bank loans in that market. In a 1 00% reserve banking system, banks will toke short-term savings and inject them into longer-term loans, which are relatively more profitable. The resultof this practice is a mismatch in the time structure of production.

The effects of this phenomena on the productive structure of the 0conomy are shown in figure 6.

CONCLUSIONS

Disaggregating the signals that entrepreneurs receive through the variations of demand and changes in interest rates into partial and reinforced signals offers the chance to explain why investment becomes so intensely biased during credit expansions. At the same time, combining this division with the analysis of savings as a set composed of cash-build savings and loanable funds it is possible to add a new dimension to the analysis of credit contraction processes.

Through a deeper study of the definitions economists use on a daily basis when designing or drafting economic policies, it might be possible to achieve a better understanding of the deviations between means, goals, and economic policy instead of claiming against unexpected consequences. The denaturalisation of savings witnessed in the evolution of modern economics is one of those consequences; and maybe one of the reasons for the continuous challenges developed economies suffer in the design of their monetary policy and financial regulations

Although the study of these two subsets is still only a first approximation, it might enable future studies into the institutional aspects and the effects of intervention of the market process' dynamics.