Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista de Ingeniería

Print version ISSN 0121-4993

rev.ing. no.35 Bogotá July/Dec. 2011

Ten Myths Undermining Latin American Housing Policy

Diez mitos que socavan la política de vivienda de Latinoamérica

Alan Gilbert

Emeritus Professor, Department of Geography, University College London, a.gilbert@ucl.ac.uk

Abstract

Housing policy in Latin America cannot be regarded as having been a huge success. Official figures show that the housing deficit is rising in most countries. Of course, solving the housing problem is difficult and complicated further by rapid urban growth and too much poverty. Nonetheless, there are many failings in current housing policy and the current paper identifies ten myths that have infiltrated the housing policy lexicon. This paper is an invitation to the region's governments to consider whether any or all of the identified myths persist within their own policies and whether those myths are as damaging as will be suggested here.

Key words

Housing, government policy, poverty, subsidy, renting.

Resumen

La política de vivienda de Latinoamérica no puede considerarse como un gran éxito. Las cifras oficiales muestran que el déficit de vivienda está incrementando en la mayoría de países. Por su puesto, resolver el problema de la vivienda es un asunto difícil, y el rápido crecimiento urbano junto con los altos niveles de pobreza hacen que sea aún más complicado. Sin embargo, hay muchas fallas en la política de vivienda actual, y este artículo identifica diez mitos que han infiltrado el léxico de la política de vivienda. Este artículo es una invitación a los gobiernos de la región para que consideren si alguno de los mitos identificados, o todos, aún persisten dentro de sus propias políticas, y si estos mitos son tan nocivos como se sugiere en este artículo.

Palabras claves

Vivienda, política gubernamental, pobreza, subsidio, arriendo.

INTRODUCTION

As in most parts of the world, housing policy in Latin America cannot be regarded as having been a huge success. Official figures suggest that the housing deficit has not been reduced over the years and in many countries has been getting larger. Whatever kind of strategy has been employed (public housing construction, capital housing subsidies, slum upgrading, or delivery of property titles) has seldom managed to dent the problem of providing shelter. It's understood that the task facing every Latin American country is enormous and the housing situation is complicated further by rapid urban growth and too much poverty; nonetheless, there are many failings in the proposed solutions of various housing policies. These weaknesses have been caused in part by certain recurrent myths that have infiltrated the housing policy lexicon. This paper is an invitation to the region's governments to consider whether any or all of these myths persist within their own policies and whether those myths are as damaging as will be suggested here.

MYTH ONE: THE HOUSING DEFICIT CAN BE ELIMINATED

In Latin America, the housing deficit in 1990 was estimated to be 38 million homes; in 2000 the deficit was 52 million and it is currently between 42 and 51 million [1]. However, "at its 16th assembly in October 2007, the Organization of High Ministers of Housing and Urbanization in Latin America and the Caribbean (MINURVI) indicated a higher level of quantitative and qualitative deprivation in the region, estimating that 40% of households in Latin America either lived in dwellings that required improvements (22%) or were living in overcrowded conditions or otherwise lacked a home of their own (18%)." If the estimate of 40% was correct, it would mean that the housing deficit in 2007 was around 60 million homes.

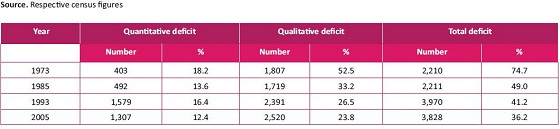

While we should be sceptical about the reliability of these figures because calculating the housing deficit faces so many problems of definition [2], two things are very clear: the deficit is not getting any smaller and Latin America will suffer from a very large housing deficit for many years. Colombia is clearly no exception to this trend, as table one demonstrates.

Table 1. Colombia: Housing deficit 1973-2005. Source. Response census figures

MYTH TWO: A REGION WITHOUT SLUMS

In 1999 the United Nations declared war on the slum'. The global housing situation was disastrous and getting worse: "Although figures vary depending on the definition, hundreds of millions of slum dwellers exist world-wide, and the numbers are growing at unprecedented rates" [3]. Since then, the number of slums' in Latin America has fallen, largely because the UN's definition of that problematic term depends principally on improving the water supply and sewerage services. Furthermore, since Latin America claims to have increased coverage markedly between the first half of the 1990s to the first half of the 2000s (from 84% to 91% and 68% to 78% respectively), the number of so-called slums declined [4].

The United Nations' campaign to improve shelter conditions is commendable, even if use of the term slum' is not [5]. The plain fact is that a slum' cannot be defined in any universally acceptable way. The kind of housing considered to be unfit clearly varies from place to place and from one social class to another. What would be considered to be a frightful slum' in the United Kingdom might be considered perfectly adequate in many parts of the world.

It is possible to identify settlements or individual houses that lack physical infrastructure, and this is broadly how the UN defines a slum'. Nevertheless, it is unwise to classify a whole area as a slum because there is usually so much variation within it, often between one household and the next. Settlements without water may be classified as slums, but what about settlements with water where some of the inhabitants cannot afford to pay for it? What is an improved sanitation facility and do water pipes always carry water? What about gentrifying areas where elegant homes are close to over-crowded rental tenements? What about the need to distinguish between the homes of owners and tenants?

Many years ago, Yelling [6] began his book on Victorian slums by stating that he would treat the word slum' "as a term in the discourse of politics rather than science. It carries a condemnation of existing conditions and, implicitly at least, a call for action." Unfortunately, years of experience show that the slum' will always be with us. Even the most dedicated official action has failed to remedy housing problems in the face of continuing poverty and inequality.

An early test of whether slums could be eliminated was conducted in the United Kingdom during the late 1920s. M'Gonigle and Kirby's [7] famous study compared the health and expenditure of a slum' population in Stockton on Tees with that of a group that had been moved to modern housing. "The results were dramatic. Although the estate to which the families moved was carefully planned and well-built, and the houses were fitted with a bath, kitchen range, ventilated food store, wash boiler and all the most modern sanitary arrangements, the death rate of the families increased by 46 per cent over what it had previously been in the slum area they left behind" [8]. The simple explanation was that in order to pay for their new housing the families were able to spend much less on food. As a result they were less healthy and died earlier.

The truth is that poor people need food and health care more than quality shelter. Hence, many actually need cheap, even rudimentary, accommodation. If cheap shelter is unavailable, they become homeless or they spend too much on housing. There is sometimes a conflict between improving the physical quality of housing and improving the life of poor people.

No city in the world is without bad housing conditions. Moreover, it is impossible to remove slums because the slum is an ideological and relational concept. Even if general housing standards rise, areas that fail to reach the new general standard will be defined as slums. As such, solving the slum problem is impossible. Those misguided governments in China, India, the Philippines and Zimbabwe that evict slum families for political or speculative reasons merely make conditions worse somewhere else.

If slums will always be with us, is the Cities without slums' campaign simply a further example of official rhetoric creating a mythical utopia in an imperfect world? Are Latin American governments being cynical, employing the promise of eliminating slums simply as a useful political slogan?

Mesa Ponentes Foto: Laura Camacho Salgado

MYTH THREE: RICH COUNTRIES ARE EXAMPLES OF GOOD HOUSING PRACTICE

There are of course positive lessons to be learned from the experience of developed countries. In Europe and North America the tragic housing conditions of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were eliminated. Gradually most houses obtained a piped water supply, connection to sewers, and where necessary better heating systems. Extreme overcrowding was also reduced. The development of mortgage markets allowed the more affluent to purchase their own home, and better transport facilities permitted suburban development where many families could live in a house with a garden.

But if the tragic living conditions described by Charles Dickens, Emile Zola or Jacob Reis have been eliminated from most developed countries, it is most certainly not the case that everyone lives in adequate housing. While few OECD governments publish figures on their housing deficits, many people live in poor quality housing and some do not even have a roof over their heads. In the United States, the incidence of homelessness is probably higher than in most parts of Latin America. According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, there were 643,067 sheltered and unsheltered homeless persons nationwide in January 2009, and about 1.56 million people used an emergency shelter or a transitional housing program between October 1, 2008 and September 30, 2009. This number suggests that roughly 1 in every 200 persons in the US used the shelter system at some point in that period.1

Governments in developed countries have tried many different approaches to solve their housing problems, but none have solved the problem of how to house the poor adequately. This has been a particular problem in the bigger cities and in the countryside, and sometimes policy options have produced unfortunate outcomes. Efforts in the UK, France, the Netherlands, and the USA to build public housing for the poor have rarely produced the anticipated results. While the early council house programme in the UK was successful, the accommodation did not always go to the poorest and such housing was often located in places that were distant from work. However, the real problems emerged when governments in the 1950s and 1960s tried to accelerate the programme and build high-rise social housing using pre-fabricated methods of construction. When combined with a lack of maintenance and too little proper management, living conditions on many of these large estates soon deteriorated. Today many are considered to be slums' and local governments are contemplating their demolition.

More recently, government efforts in the United States to turn poor families into private homeowners have proved disastrous. Previously conservative mortgage lenders were transformed into profligate lenders, sometimes lending money to families with poor credit rating and little or no income. We are all now suffering the consequences of the sub-prime crisis. Not only has it led to macro-economic problems and rising unemployment, but it has also led to many of the beneficiaries' of loans losing both their savings and their homes. According to the US firm RealtyTrac, around 3.8 million foreclosures were filed in 2010, and that number could balloon to about 6 million by 2013[9].

The lesson to be drawn from these two examples is that no government is capable of resolving its housing crisis (in whatever form it takes) if the country exhibits widespread poverty and unemployment. If the country is also unequal, and over the past thirty years most developed countries have become more unequal, then the task is even more difficult.

It would be useful to see UN-Habitat supplement its web pages advertising best practice' with an equivalent of worst practice' [10]. Governments across the world have perhaps more to learn from the mistakes of others than from the too often romanticised success stories.

MYTH FOUR: WHEN HOME PRICES FALL THER IS A HOUSING CRISIS

The British press, prompted perhaps by real estate interests and the high proportion of home owners in the UK, regularly complain when house prices fail to rise. If prices fall it seemingly constitutes a housing crisis. I would suggest that the opposite is the case. The more house prices rise relative to average income, the harder it is for young families and poor households to buy a home. As such, a housing crisis is more likely to be caused by rising prices; indeed, this has been case in the UK in recent years when, in response, banks began to offer mortgages of up to the full value of the property.2 Servicing such large mortgage debts was only possible for most households if they contained two income earners. After 2008, when people started to lose their jobs, the true horror of their situation became evident. The only beneficiaries of rising house prices are real-estate agents and those households old enough and fortunate enough to have paid off their mortgage. Older Britons have gained at the expense of the young. Even the building industry suffers when people cannot afford to buy very expensive houses.

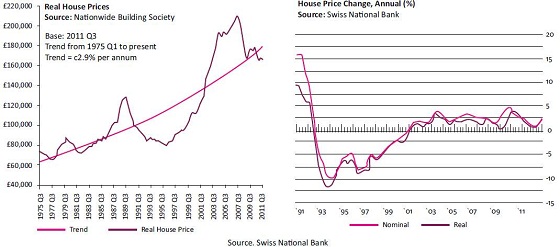

To support the case that well-functioning housing markets are not consistent with rapidly rising real housing prices, consider the trend in house prices in the UK and Switzerland in recent years. The UK has seen rapid increases, Switzerland has not. The reader should be able to guess which country has the fewest households living in inadequate housing!

Figura 1. House price change in UK and Switzerland

MYTH FIVE: IN WEALTHY COUNTRIES, EVERYONE OWNS THEIR OWNHOME

In Europe there is an enormous variation in the proportions of families that own their own home. In Romania 97% of families own their home, but in Germany only 56% do, and in Switzerland a mere 35% do. Given that Romania is the EU's poorest country, and that Germany and Switzerland are among the richest, the automatic assumption that there is a positive correlation between income per capita and ownership comes into question [11].

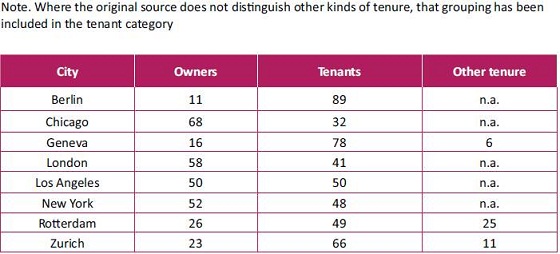

The lack of any real correlation is even more obvious when the tenure structure of very large cities is considered. Table three shows that some of the world's wealthiest cities contain a majority of tenants (New York and Los Angeles) and some of the world's most liveable cities contain even larger majorities, e.g. Geneva and Zurich.

Table 3. Tenure structure of major cities in developed countries.

The ideologically motivated link that is commonly drawn between home ownership and good housing conditions is false. Many families enjoy home ownership in very poor countries, often in rudimentary shelter lacking services. Many households in rich countries rent.

MYTH SIX: A PRINCIPAL AIM OF GOVERNMENT SHOULD BE TO CREATE A NATION OF HOMEOWNERS

Recent governments have promised to turn Colombia into "un país de propietarios", and virtually every other Latin American government has followed a similar line. I am regularly misinformed by housing officials in the region that home ownership is part of Latin Americans' culture. It most certainly is not, any more than it was in the United Kingdom before one government after another gave more substance to the myth. In the UK, around 90% of households rented accommodation in 1918 and a majority still rented as recently as 1970. In Britain, the desire for home ownership has been generated by excessively generous incentives to mortgage holders, a failure to tax imputed rent or capital gains, and a neglect of the rental housing sector. The British population, like that of the US, was bribed to become home owners.

Many households do not need to own and currently are content to rent. Those who do not have permanent jobs, students, new urban arrivals and the recently separated or divorced, all need temporary accommodation. Those who want to set up a business cannot afford to use their limited capital to buy a house. Families without children may wish to take advantage of a central location; they will have years of staying at home once children come along! These households do not need their own home now - even those that dream of eventually becoming home owners [11, 12, 13, 14].

The Colombian constitution declares that every citizen has the right to a decent home' (una vivienda digna). It is not easy to clearly establish the meaning of a decent home', but the sentiment is reasonable. What is not acceptable is that the decent housing has to be provided through full ownership. If that is the case then the majority of Swiss people do not live in decent housing! If Zurich and Geneva, with more than three-quarters of their inhabitants renting accommodation, can offer such an excellent quality of life and in the process avoid a sub-prime crisis, that experience suggests that rental tenure offers a society some advantages.

MYTH SEVEN: POOR FAMILIES HAVE A RIGHT TO HOME OWNERSHIP

In a nation of homeowners, every poor family has the right to ownership. But how is it possible to turn this right into reality?

From the 1920s on, every government in Latin America established housing agencies to build houses for the poor. In Colombia the Instituto de Crédito Territorial (ICT) was established in 1939, and for a long time was regarded as a worthy institution that built and designed good quality homes [15, 16]. The problem was that it could never keep up with demand, and increasingly its homes went not to those most in need but to better off families or those with political connections. Eventually, the combination of too many poor families, too few resources, excessive populism and poor administration killed the institute [17]. Throughout the region, governments found that they could not build enough public housing to satisfy demand. In addition, when they tried to build more units at lower cost they usually produced inadequate accommodation. Public housing projects in the 1960s were: "small in scale, largely unaffordable by the poor, poorly targeted, and largely inefficient" [18]. If that were true of the 1960s little changed during the 1970s and 1980s. In poor countries, it is obvious that too many households need homes and too few governments have the resources to build even a fraction of the homes required.

From the middle 1980s most governments began to adopt a different approach, influenced in no little part by the Chilean experience. In an attempt to sweep away socialism, stimulate the private construction sector and house the poor, the Pinochet government invented the up-front capital subsidy in 1977 [ 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. In the future, social housing would be built by the private sector. Instead of the government specifying what the private sector should produce, builders would be free to compete in providing consumers with the kind of housing that they wanted. The assumption was that private enterprise would produce more cheaply than under the public contracting system as well as provide a wider choice of housing for the poor.

To stimulate demand, housing subsidies would be given to poor families to increase effective demand for social housing. The Chilean government devised a way of allocating subsidies to families who were both poor and prepared to help themselves. The test of the latter was their willingness to accumulate savings; the longer their savings record and the greater their savings, the more likely they were to get a subsidy. The subsidy and savings would not cover the whole cost of the house and the difference would be covered by a mortgage. The new subsidy mechanism was not an immediate success and some years passed before it began to function effectively. Ironically, its best results were achieved under the democratic governments of the 1990s. The governments of Patricio Alywin and Eduardo Frei began to boast that Chile was now the only Latin American country that was managing to cut its housing deficit.3

This ABC package of savings (ahorro), subsidy (bono) and credit was adopted in modified form in numerous Latin American countries including Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama and Peru. The logic behind the scheme is impeccable. Households have to demonstrate that they are worthy of a subsidy by saving for the deposit, their reward is the subsidy which helps them to purchase a privately built home, and because there are so many poor families, the credit element reduces the cost to the state.

Unfortunately, the last ingredient introduces a critical flaw. For a variety of reasons private banks are not keen to lend money to poor families, and the latter often have too low a credit rating to convince the banks otherwise. This problem was discovered very early in Chile and the answer was to insist that the Banco del Estado provide the mortgages. Alas, this was proved an unsatisfactory answer insofar as many of the beneficiaries of the loans were unable or unwilling to pay interest on their loans. This is the reason why the credit element is now missing from Chilean policy.

In Colombia there is an additional problem. According to DANE, 60% of Colombian families in 2008 earned less than two minimum salaries and were therefore too poor to save very much [24]. The consequence of limited savings and credit has been that the government has struggled to deliver the subsidies it has approved. Between 2006 and 2009 the Fondo Nacional de Vivienda assigned subsidies to 172,000 families, but only 63% were taken advantage of.

Of course an obvious answer to the lack of credit and savings is to offer the poor much larger subsidies. While such an approach either increases the cost to the state or reduces the number of subsidies available, it has been tried in Chile and South Africa. However, experience in those countries suggests that larger subsidies only help partially because other problems emerge.

First, subsidised accommodation is often built to very poor standards or is very small in size. In Colombia, some VIP housing has had a floor area of only 36m2 and has been six floors up in a building with no lift. Generally, highly subsidised housing is located in inconvenient locations built where land is cheap. In South Africa, such housing is often tens of kilometres from the main centres of employment.

Second, in South Africa, and to some extent in Colombia, many beneficiaries have given up their heavily subsidised homes because they could not afford to pay for the upkeep of the house, the taxes, service charges and maintenance. Others have given up the house because of the distance between home and work. Their response has been to sell, rent or bequeath the house to another household.

Third, accurate targeting is at the heart of the subsidy system. In Chile, the government has developed a very good system of identifying the poor. Unfortunately, accurate targeting leads to groups of very poor families being allocated housing in the same neighbourhood. These families have too little income to develop businesses or even to maintain their homes. The danger is that these areas of social housing may become ghettos from which no one ever escapes. They run the risk of becoming slums' in the not too distant future.

MYTH EIGHT: INFORMAL HOUSING NEVER PROVIDES A DECENT HOME

In an ideal world poor people would not have to build their own shelter, as so many do in Latin America. The difficulties of living in a shanty while constructing a house, surviving for some years without proper services and with problematic education, health and transport facilities is bad enough; but to envisage doing this while living in a dangerous physical environment, subject to storms, earthquakes or floods, beggars belief. And yet in an environment of poverty there is often little alternative.

Nevertheless, a majority of the Latin American population has done just this, and to the surprise of many, a large number of families have done a fine job.

Figura 2. 'Mi Casita': Evolution of a house in casablanca, Suba

Alas, far too many governments in Latin America recognise this reality, and some (particularly authoritarian regimes) have been wont to evict self-help settlers. Today, most governments have accepted that it is more sensible to upgrade such settlements and remove only those that are located in particularly dangerous places.

But what about the future? It seems that few governments today are willing to accept either that an informal dwelling can ever constitute a proper home or that self-help housing is an inevitable consequence of urban poverty. As such, no government in the region is creating sites and service programmes to accommodate the future growth of self-help housing. Most are pretending that capital subsidies and credit programmes will create enough formal housing to stem the growth of self-help settlement. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that any Latin American government is managing to reduce its housing deficit.4

In that case, it is essential that Latin American governments accept that well-constructed and planned informal housing is a valid supplement to formal social housing. This means that governments should continue with recent efforts to service and upgrade existing settlements. The national government and certain local governments in Colombia have performed a major service in providing water and sewerage to low-income settlements in the country. Between 1985 and 2005 national water coverage improved from 57.8% to 83.2%, and sewerage from 47.1% to 63.4% in 2005. In Bogotá and Medellín virtually the whole population benefits from these essential services.

What is missing is any real effort to plan for the future expansion of informal settlement. As a result, every government in the region is playing a constant game of catch up. What good does it serve to provide infrastructure for existing informal settlements if nothing is done to prevent new ones from being formed? The answer was provided years ago – sites and service projects' [25].

There are two essential ingredients in planning for the future. First, governments must prevent the illegal occupation of land, particularly land that is dangerous for human settlement, expensive to service or is destined for public use. Second, governments should provide alternative areas for informal settlement. Such areas need not have a full range of services, but would be laid out in a way that they can be installed efficiently and cheaply at a later date. Here the poor could build decent homes more cheaply and quickly than they do now, especially if technical advice and micro-credit were available and the cost of building materials could be kept down.

MYTH NINE: THERE ARE TOO FEW RESOURCES

It is obvious from the arguments so far that governments in poor countries cannot solve the housing problem due to the amount of poverty, the size of the problem, and the lack of resources. Nevertheless, if housing really were a priority for Latin American governments many more resources could be dedicated to the task.

First, most Latin American governments spend very little on housing as a proportion of GDP; in 2008-9 only Brazil and Nicaragua spent more than 2% on social housing [4]. In monetary terms, only three Latin American countries spent more than US$125 per capita on social housing, and Colombia's spending between 2002 and 2009 averages out at a mere US$16 (0.5% of GDP). These amounts are trivial when compared to the amounts governments spend in many developed countries.5

Second, Latin American housing budgets are often poorly structured, target the wrong issues and are too often undermined by inefficiency and corruption. The later history of ICT and subsequently that of Inurbe provide ample evidence of that in a Colombian context.

If authorities were prepared to spend more on housing, and indeed social issues in general, the potential for tax generation is considerable. Various sources of revenue that could be used to help improve the housing situation are simply not collected, notably betterment and capital gains taxes. The Colombian national plan of 1971, Las Cuatro Estrategias, embraced the argument that an accelerated process of urbanisation would create wealth that could be used to house and service the growing population [26]. The urban reform acts of 1989 and 1997 decreed how that task could be accomplished: the contribution to develop that is "the responsibility of the owners of those urban or suburban properties or real estate that gain added value as a result of social or state efforts

Unfortunately, as many authors have pointed out, implementation of urban reform in Colombia has been disappointing [27, 28, 29] In Bogotá in 2009 the property tax collected per household was only US$189, and the average added value was US$2.5. In other cities in Latin America the tax yield is even lower. In February 2011, Alfonso Barrera, the mayor of Quito, told me that the property tax collected per household averaged out at a mere US$25.

The lesson is clear. Urbanisation creates wealth for property owners and too little of that wealth is taxed. If governments really wanted to spend more on social housing, they could do so.

MYTH TEN: THERE IS AN ENORMOUS AMOUNT OF DEAD CAPITAL IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

For some, the Peruvian Hernando de Soto has provided the answer to the housing crisis in Latin America as well as its employment and development problems. He explains the current problem facing the poor as follows: "Even in the poorest nations the poor save. The value of savings among the poor is, in fact, immense – forty times all the foreign aid received throughout the world since 1945." "But they hold these resources in defective forms: houses built on land whose ownership rights are not adequately recorded, unincorporated businesses with undefined liability, industries located where financiers and investors cannot adequately see them. Because the rights to these possessions are not adequately documented, these assets cannot readily be turned into capital, cannot be traded outside of narrow local circles where people know and trust each other, cannot be used as collateral for a loan, and cannot be used as a share against an investment" [30].

The priority for government, therefore, is to give the poor title deeds. Titles will give them access to credit and that will improve the functioning of the land and property markets. Of course, there is nothing particularly new or controversial about this policy. De Soto himself pushed this message very hard in his earlier book and he has been actively involved in regularisation and legalisation programmes in Peru for some years [31]. Nor is it a new message in Washington, given that both the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank have been saying something very similar for some time [32].

Property titling has its place, provided it does not come at too high a price and is supported by some kind of enforcement process. However, its defenders are too up-beat. Recently de Soto has claimed that the dead capital of the poor in 12 Latin American countries amounts to US$1.2 trillion [33]. Unfortunately, the method he uses to calculate this staggering sum is less than transparent [34].

Legal titles will not transform Third World housing for one very simple reason: there are too many families too poor to afford decent shelter and are sufficiently wise not to borrow much from banks. In the face of abject poverty, offering to formalise home ownership achieves little for the owners and nothing at all to help hundreds of millions of tenants. Indeed, in the pirate settlements of Bogotá credit seems to be more freely available at the initiation of the settlement than later. Pirate developers offer mortgages to poor people, private banks do not [35, 36].

CONCLUSION

In a poor and very unequal Latin America it is foolish to pretend that the housing problem can be solved. Since there are serious housing problems in Europe and North America, countries which are both much richer and more equal than those in Latin America, governments should stop promising to eliminate the housing deficit.

Yet this is precisely what many Latin American governments pretend. One day, soon, everyone will not only live in a decent home but will own it too! The reality is different.

It is time that governments were more honest. They need to stop pretending that current programmes, some of which are admirable, can do much more than stem the tide of homelessness and informal construction. They should question some of the myths that they currently peddle. If they truly aim to improve housing conditions they need to generate more resources from the very process that is seemingly causing the problems: urbanisation. With those resources they could spend more on shelter, devise better and more equitable housing policies and thereby reduce some of the problems.

Of course they will never solve the problem so long as property markets push up land and housing prices, poor people earn so little and governments are so reluctant to tax capital gains on property. In this respect, we might perhaps argue that Latin America suffers less from a shelter problem than from a governance problem.

FOOT NOTES

1 The baseline, 1.6 million people, is the number of people who were homeless from October 2009 through September 2010, as documented by The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress (AHAR).

2 The most foolish banks offered loans of up to 125% of the value of the property because they assumed that house prices would continue to rise.

3 Most Latin American countries calculate their housing deficit by estimating the difference between the numbers of households in the country and the number of households living in adequate accommodation. The method of calculation varies from country to country and is rarely reliable; the housing deficit is popular among politicians and lobbyists wishing to highlight the need for more investment in the sector. The South Africans also calculate a housing deficit. For criticisms of the concept and an explanation of the ways in which it can be calculated see Fresneda (1997).

4 Even Chile, the undoubted success story of housing in Latin America (along perhaps with Costa Rica), probably now has a larger housing deficit as a result of the 2010 earthquake.

5 The French government in 2007 spent 14.2 billion Euros to help almost six million households to cover their housing costs (http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?ref_id=T10F072). In the UK, "the chancellor, George Osborne, said spending on housing allowances had risen by 50% over the past decade to £21bn a year" (http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/jun/22/budget-housing).

REFERENCES

[1] UN-Habitat. Affordable land and housing in Latin America and the Caribbean, Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Program, 2011. [ Links ]

[2] O. Fresneda. "Magnitud del déficit habitacional en Colombia", Desarrollo Urbano en Cifras. Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 174-245. [ Links ]

[3] World Bank/UNCHS (Habitat). Cities Alliance for Cities Without Slums: action plan for moving slum upgrading to scale, Special Summary Edition. 2000, p. 15. [ Links ]

[4] UN-ECLAC. Social panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago: ECLAC Books, 2010, p. 252. [ Links ]

[5] A.G. Gilbert. "The return of the slum: does language matter?", International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. Vol. 31, 2007, pp. 697-713. [ Links ]

[6] J.A. Yelling. Slums and slum clearance in Victorian London. London: Allen and Unwin, 1986. [ Links ]

[7] G.C.M. M'Gonigle and J.Kirby. Poverty and public health. Left Book Club ed. London: Gollancz, 1936. [ Links ]

[8] P.L. Garside. "«Unhealthy areas»: Town planning, eugenics and the slums, 1890 1945", Planning Perspectives, 3, 1988, pp. 47 58. DOI: 10.1080/02665438808725650 [ Links ]

[9] Reuters. "Once a nation of homeowners, U.S. turns to rentals", 2011. [online]. Fecha de consulta : Septiembre 2011. Disponible en : http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/08/16/us-usa-housing-idUSTRE77943O20110816 [ Links ]

[10] [en línea] Disponible en: http://www.unhabitat.org/bp/bp.list.aspx [ Links ]

[11] UN-Habitat. Rental housing: an essential option for the urban poor in developing countries, Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Program, 2003. [ Links ]

[12] C. Escallón (comp.). Arrendamiento alternativa habitacional y vivienda popular en Colombia, Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes y Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá, 2010. [ Links ]

[13] A.G. Gilbert, O.O. Camacho, R. Coulomb and A. Necochea. In Search of a Home: Rental and Shared Housing in Latin America. London: UCL Press and the University of Arizona Press, 1993. [ Links ]

[14] UN-HABITAT. A policy guide to rental housing in developing countries, Nairobi: UN-HABITAT, 2011. [ Links ]

[15] C. Gutiérrez Cuevas. "ICT: 50 años cumpliendo con Colombia", Revista Camacol, Vol. 39, 1989, pp. 10-22. [ Links ]

[16] J.I. Laun. "El estado y la vivienda en Colombia: análisis de urbanizaciones del Instituto de Crédito Territorial en Bogotá." En: C. Castillo (ed.) Vida urbana y urbanismo, Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, 1977, pp. 295-33. [ Links ]

[17] E. Pacheco. "ICT: hay que actuar para salvarlo", Revista Camacol. Vol. 39, 1989, pp. 23-27. [ Links ]

[18] S. Mayo. "Subsidies in Housing" En: Sustainable Development Department Technical Papers Series SOC-112. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank, Julio 1999. [ Links ]

[19] A.G. Gilbert. "Power, ideology and the Washington Consensus: the development and spread of Chilean housing policy", Housing Studies 17, 2002, pp. 305-24. [ Links ]

[20] G. Held. Políticas de vivienda de interés social orientadas al mercado: experiencias recientes con subsidios a la demanda en Chile, Costa Rica y Colombia. Serie Financiamiento del Desarrollo 96. Santiago, Chile: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), 2000. [ Links ]

[21] A. Pérez-Iñigo González. El factor institucional en los resultados y desafíos de la política de vivienda de interés social en Chile. En: CEPAL Serie Financiamiento del Desarrollo, Santiago: Naciones Unidas, 1999. [ Links ]

[22] E. Rojas. "The long road to housing sector reform: lessons from Chilean housing experience", Housing Studies 16, 2001, pp. 461-83. [ Links ]

[23] J.G. Valdés. Pinochet's economists: the Chicago School in Chile, Cambridge U.P., 1995 [ Links ]

[24] M.E. Pinto, "Propuestas para la nueva política habitacional", II Foro de Vivienda, ASOBANCARIA, 3 de diciembre 2010. [ Links ]

[25] World Bank. Sites and service projects, Washington D.C.: World Bank, 1974. [ Links ]

[26] DNP. Las cuatro estrategias, Bogotá: DNP, 1971. [ Links ]

[27] F. Giraldo (ed.). Reforma urbana y desarrollo social, Camacol, 1989. [ Links ]

[28] F. Giraldo. Ciudad y crisis: hacia un nuevo paradigma?, Bogotá: 1999. CENAC, FEDEVIVIENDA, Tercer Mundo Editores, Ensayo & Error, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 1999. [ Links ]

[29] L.F. Fique Pinto. Vivienda social en Colombia: políticas públicas y habitabilidad en los años noventa, Bogotá: Colección Punto aparte, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2006. [ Links ]

[30] H. De Soto, The mystery of capital, Basic Books, 2000. [ Links ]

[31] E. Panaritis, "Do property rights matter? An urban case study from Peru", Global Outlook: International Urban Research Monitor, April 2001, pp. 20-22. [ Links ]

[32] World Bank, Housing: enabling markets to work, A World Bank Policy Paper, Washington D.C.: 117, 1993. [ Links ]

[33] Building Opportunity for the Majority, Washington D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank, 2006. [ Links ]

[34] A.G. Gilbert. "On the mystery of capital and the myths of Hernando de Soto: what difference does legal title make?" International Development Planning Review 24, 2002, pp. 1-20. [ Links ]

[35] A.G. Gilbert. "¿Una casa es para siempre? Movilidad residencial y propiedad de la vivienda en los asentamientos autoproducidos", Territorios 6, 2001, pp. 51-74. [ Links ]

[36] A.G. Gilbert. "Financing self-help housing: evidence from Bogotá, Colombia", International Planning Studies 5, 2000, pp. 165-90. [ Links ]