Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Innovar

Print version ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar vol.21 no.39 Bogotá Jan./May 2011

Ronald M. Rivas* & David Mayorga**

* Associate Professor of Management. Department of Management and Marketing. Canisius College. Buffalo, New York. E-mail: rivasr@canisius.edu

** Decano. Facultad de Administración y Contabilidad. Universidad del Pacifico. Lima, Perú. E-mail: mayorga_dj@up.edu.pe

Recibido: julio de 2010 Aprobado: noviembre de 2010

Abstract:

We study the multinationalizationâthe decision to establish foreign direct investment (FDI)âof Peruvian restaurants. Despite a long exporting tradition, many Peruvian firms have only recently become multinational enterprises (MNEs). The analysis of eighty-two cases of Peruvian restaurants FDI in the Americas, Europe and Asia, reveals several findings. First, it confirms the received view that Multilatinas take a long time to become MNEs, and they become MNEs after changes in the home country that follow structural reform induce them to upgrade their competitiveness to international levels. However, unlike previous studies, we found that Peruvian restaurants expand to countries with proximate as well as with distant psychic distance. These findings are at odds with the gradual internationalization model and the eclectic paradigm. Second, this study found support for the institutional proposition of internationalization, that is, institutional pro-market reforms benefit domestic firms over foreign MNEs, which facilitate domestic firms' multinationalization. Peru has seen a significant economic recovery during the last decade, which just recently has created opportunities for the emergence of Peruvian Multilatinas. Third, this study found support for the RBV proposition of multinationalization namely, that unique business level strategies have different multinationalization processes.

Keywords:

multinationalization, internationalization, Emerging countries, Multilatinas, Multinational corporation, Peru, Peruvian restaurants.

Resumen:

Esta investigación estudia la multinacionalización -es decir la decisión de establecer inversión extranjera directa (IED)- de los restaurantes peruanos. A pesar de una larga tradición exportadora, muchas empresas peruanas se han convertido recientemente en multinacionales. El análisis de 82 casos de inversión extranjera directa de restaurantes peruanos en América, Europa y Asía revela datos interesantes. El estudio confirmó la percepción que las Multilatinas toman un largo tiempo en llegar a ser multinacionales. A diferencia de estudios anteriores, se encontró que los restaurantes peruanos se expandieron tanto a países próximos como lejanos en términos de la distancia psíquica entre el Perú y el país de la inversión. Estos resultados están en desacuerdo con lo planteado en el modelo gradual de internacionalización y el paradigma ecléctico. Asimismo, el estudio apoya la teoría institucional de internacionalización. Las reformas institucionales y económicas favorecen el crecimiento de empresas locales, facilitando así la multinacionalización de la empresa local. Perú ha experimentado una significativa recuperación económica la última década, que recientemente ha creado oportunidades para la aparición de las multilatinas peruanas. Finalmente, este estudio sugiere que la teoría de crecimiento empresarial desde la perspectiva basada en los recursos da una explicación plausible de la multinacionalización de las empresas Latinoamericanas. En particular esta teoría sugiere que diferentes modelos de negocios conducen a diferente ubicación geográfica de IED de las multilatinas.

Palabras clave:

multinacionalización, internacionalización, economías emergentes, multilatinas, corporación multinacional, Perú, restaurantes peruanos.

Résumé:

Cette recherche étudie la multinationalisation - à savoir la décision d'établir l'investissement étranger direct (IED) - des restaurants péruviens. Malgré une longue tradition d'exportation, de nombreuses entreprises péruviennes sont récemment devenues des multinationales. L'analyse de 82 cas d'investissements directs étrangers de restaurants du Pérou en Amérique, en Europe et en Asie révèle des faits intéressants. L'étude a confirmé l'impression que les Multilatinas prennent un certain temps pour devenir des multinationales. Contrairement aux études antérieures, nous avons constaté que l'expansion des restaurants péruviens est à la fois proche et lointaine en termes de distance psychique entre le Pérou et le pays d'investissement. Ces résultats sont en désaccord avec les déclarations contenues dans le modèle graduel d'internationalisation et le paradigme éclectique. L'étude prend également en charge la théorie institutionnelle de l'internationalisation. Les réformes institutionnelles et économiques favorisent la multinationalisation des entreprises locales. Le Pérou a connu une reprise économique significative au cours de la dernière décennie, ce qui a récemment créé des opportunités pour l'émergence de multinationales au Pérou. Finalement, cette étude suggère que la théorie de la croissance des entreprises en ce qui concerne les ressources fournit une explication plausible de la multinationalisation des entreprises latinoaméricaines. En particulier, cette théorie suggère que les modèles d'affaires différents entraînent une localisation géographique différente de l'IED par des multinationales.

Mots-clefs:

multinationalisation, internationalisation, économies émergentes, multilatinas, entreprise multinationale, Pérou, restaurants péruviens.

Resumo:

Este trabalho estuda a multinacionalização - ou seja, a decisão de estabelecer o investimento direto estrangeiro (IDE) - dos restaurantes peruanos. Apesar da longa tradição de exportação, muitas empresas peruanas recentemente se tornaram multinacionais. A análise de 82 casos de investimento direto estrangeiro dos restaurantes peruanos na América, Europa e ásia revela fatos interessantes. O estudo confirmou a percepção de que as Multilatinas demorar muito tempo para tornarem-se multinacionais Ao contrário de estudos anteriores, verificamos que os restaurantes peruanos investiram no exterior em países próximos e distantes em termos de distância psíquica entre o Peru e o país de investimento. Estes resultados estão em desacordo com as declarações do modelo de internacionalização gradual e do paradigma eclético. O estudo também apóia a teoria institucional de internacionalização. As reformas econômicas incentivaram o crescimento das empresas locais, facilitando assim a internacionalização das mesmas. O Peru tem experimentado uma recuperação econômica significativa na última década, que recentemente criou oportunidades para o surgimento de multinacionais no Peru. Finalmente, este estudo sugere que a teoria do crescimento dos negócios a partir da perspectiva baseada em recursos fornece uma explicação plausível para a internacionalização das empresas latino-americanas. Em particular, esta teoria sugere que os modelos de negócios diferentes levam a diferente localização geográfica do IDE por multinacionais.

Palavras chave:

multinacionalização, internacionalização, economias emergentes, multilatinas, empresa multinacional, Peru, restaurantes peruanos.

Introduction

How different is the multinationalization process of companies from small emerging economies and what are the more prevalently strategies that such multinationals use? The rise of multinational corporations from emerging countries is reshaping the global competitive landscape. The value of outward FDI stock from developing countries rose from $130 billion in 1990 to $860 billion in 2003, South-South FDI represents one third of all FDI going to developing countries. These flows increased from 15 USD billion in 1995 to 50 USD billion in 2003 (Aykut & Goldstein, 2006; Santiso, 2007). In particular, emerging corporations from Latin America, or Multilatinas, have attracted interest of researchers (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; da Silva et al., 2009; Santiso, 2008) and practitioners alike (Martinez et al., 2003; Toledo, 2008). Companies from Argentina, Mexico and Brazil that were dominant multilatinas in the 1990s, were joined by emerging multilatinas from Chile, Colombia, Venezuela and Peru in the last two decades (AméricaEconomía, 2008).

The study of multinationalization, which is the process of international expansion via foreign direct investment (FDI), is explained by two main theoretical streams, namely, the incremental internationalization model and the eclectic paradigm. The incremental internationalization model originally proposed that liability foreignness, the relative psychic distance between the home country and the FDI host country, acted as a dampening of multinationalization speed. The liability of foreignness restrained the direction of FDI from closer to gradually expanding to further psychic distance (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). Firms have recently revised this model to include liability of Outsidership, in relation to the relevant global network. In this revised perspective, liability of Outsidership more than psychic distance is the root of uncertainty associated to multinationalization (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). The eclectic paradigm proposed that multinationalization is the result of firms exploiting ownership, location, and internalization advantages (Dunning, 1979, 1980). These models emerged and were tested mainly in the context of multinational from developed countries. Recent studies have raised the issue of extending (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; Cuervo- Cazurra & Dau, 2009) or altogether developing a new theory that address the peculiarities of multinationals from emerging economies (Guillén & García-Canal, 2009).

These extensions address the multinationalization process or large multinationals from the largest countries in the Latin America, such as Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. However, there few little empirical evidence revealing the multinationalization process of multilatinas from small emerging countries. In addition, studies addressing multilatinas use large diversified multinationals with operations in multiple industries. Such research design is intended to generalize multinationalization practices at the corporate strategy level of analysis. However, a multiple industry research design lends itself to confound firm strategies at the business unit level of analysis.

Therefore, in this paper we analyze the multinationalization of developing country MNEs. In particular, we study the multinationalization strategies at the business level of analysis. We use a sample of Peruvian restaurants to illustrate the process. Peruvian restaurants present perhaps the most remarkable example of multinationalization of small companies, based on individual skills, ownership advantage, and organizational capabilities. Restaurants require a small investment in comparison to the FDI necessary to expand large technology (e.g., Embraer), natural resources exploitation (e.g., PetroBras), industrial manufacturing (e.g., Cemex), or packaged food distribution (i.e., Grupo Bimbo). In addition, restaurants face stiff competition from already established large foreign fast food multinationals (e.g., McDonalds, Yum! Brands, or Burger King).

The analysis confirms previous findings that multilatinas take a long time to become MNEs, and they become MNEs after changes in the home country that follow structural reform induce them to upgrade their competitiveness to international levels. Peru has seen a significant economic recovery during the last decade, which just recently has created opportunities for the emergence of Peruvian multilatinas. Second, this study compares eight factors affecting multinationalization, namely, 1) time of FDI, 2) geographic, 3) cultural, 4) development distance, 5) market integration in products, 6) market integration of factors of production, 7) growth of domestic market, and 8) business models. We found that Peruvian restaurant's multinationalization speeded up after the implementation of economic reforms. Their domestic growth and international expansion is relatively faster that the growth of foreign fast food multinationals in Peru. In addition, we found that all Peruvian restaurants FDI occurred in countries that had high market integration. Both findings lend additional support to the institutional hypothesis of expansion of domestic firms, namely, that domestic firms rather than foreign multinational firms are the main beneficiaries of local and regional institutional premarket reforms.

Finally, this paper introduces a RBV analysis of business model of multinationalization strategies. We found that Low Cost leaders' restaurants grew faster in the domestic market and had higher levels of FDI than Premium Niche restaurants. In addition, the direction of multinationalization varied by business model. Low Cost leaders' restaurants concentrated their FDI in Central America. A RBV explanation of that behavior is the search to increase their organizational capabilities via close observation and learning of multinational competitors. For instance, Guatemala has almost all the franchises in the world in their domestic market. Peruvian restaurants could see such markets as a relatively safe learning ground on how to learn to compete with multinational franchises operations (e.g., Bembos). In contrast, Premium Niche restaurants expanded simultaneously to both psychic-proximate markets in the Southern Cone of South America, and psychic-distant markets such as North America, Europe and Asia (e.g., Astrid y Gastón). A RBV explanation of this behavior suggests that Premium Niche companies expanded based on the acceptance of a business model designed to please global customers with an innovative cuisine that uniquely fused Peruvian and European culinary traditions.

The paper is organized as follow. In the next section, we present the research design to analyze the case studies. A discussion of insights obtained from the analysis follows their description. We conclude with a summary of contributions and future research.

Research design

To establish external validity of the findings, this paper replicated findings with the use of variables employed in previous studies (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008). Cuervo-Cazurra (2008) used cultural and development distance in addition to time of FDI as measures psychic distance and gradual internationalization. This paper also analyzes growth of domestic firms vis a vis foreign multinationals. This is to address new theorizing on the impact of the economic deregulation on domestic firms (Cuervo-Cazurra & Dau, 2009). In addition, this paper introduces measures of market integration, namely, products-market and factorsmarket integration (Rivas et al., 2006). Recent theorizing on semiglobalization suggests that incomplete market integration constrains multinationals expansion behavior (Ghemawat, 2003). Third, based on the resource Based View of the firm (RBV) this paper introduces archetypical business strategies to explain multinationalization strategies of small restaurants.

We followed the general guidelines for case analysis (Maanen, 1983; Miles & Huberman, 1984 [1990]; Yin, 1989). This study performs a literal replication of previous case research of multilatinas (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008), an expands the analysis to a theoretical replication following the design recommended by Yin (1989).

We selected the cases from secondary data sources in Peru. Arellano Marketing, a Peruvian consulting company, estimated 18,144 restaurants in Lima in 2002, a number that grew to approximately 31,450 by 2009. We crossreferenced two local databases, namely, the directorio de datos categorizados (June 2009), and the directorio de empresas (DIME), and we obtained 86 top restaurants. The directorio de datos categorizados (directory of categorized data) was developed by the Ministry of Commerce and Tourism (MINCETUR). The DDC database has information on restaurants registered in the roster of MINCETUR. The directorio de empresas (DIME) was elaborated by a consulting company namely, IPSOS APOYO Opinion y Mercado. The DIME database has information on companies located in Lima and surrounding provinces categorized by the Peruvian industry code (CIIU). We used the CIIU 5520 corresponding to restaurants and bars.

From cross-referencing the DDC and DIME databases, we selected the 86 restaurants from Lima that were listed on both databases. From these 86 restaurants, we selected those that had at least one instance of FDI, and excluded any foreign multinational fast food restaurant. The resulting sample had 16 restaurants. Most of these restaurants opened various locales in different countries per year after 2000. We recorded 38 company/year events of investment abroad resulting from 1989 to 2009 for 82 FDIs.

Table 1 shows a description of our final sample, in comparison to the top foreign multinational fast food franchises (Pizza Hut, Burger King, KFC, and McDonalds). The sample has a limitation of size, but presents a very interesting set of rising stars. Recognizing the economic potential for this business segment, the Peruvian government has designated the culinary industry as "producto bandera", which is a category designating eight business segments deemed of national marketing efforts. Restaurants like Astrid y Gastón have received much international notoriety for their culinary innovations such as the Fusion cuisine, yielding dishes with an intriguing blend of European and native flavors and spices. Founder and entrepreneur Gastón Acurio has achieved the status of a local hero. Acurio along with other entrepreneurs founded the Asociación Peruana de Gastronomía (APEGA) to promote Peruvian cuisine at domestic and international markets.

Insights from the case studies

We performed an analysis of time to start multinationalization and location of first multinationalization to replicate findings of previous research on multinationalization of multilatinas (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008).

Time to start multinationalization

We coded the year of the first FDI and compared this to the year when they were created. On the y-axis, we have the year when the firms first established FDI. On the x-axis, we have the year when the firms were created.

Figure 1 findings are in line with previous research of internationalization of multilatinas (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008). Figure 1 confirms that Latin American firms started multinationalization much later than they were created, with an average of 12 years lapsing between their foundation and the start of multinationalization. In addition, these findings lend support to the institutional hypothesis of internationalization, namely, that pro-market reforms in Latin America benefited internationalization of domestic firms(Cuervo-Cazurra & Dau, 2009).

Structural pro-market reforms started in 1990 with the first government of President Alberto Fujimori. Economic reforms were implemented in response to a crisis that erupted in the mid eighties, during President Alan García's first term in office. President Alan Garcia served a first term as President from 1985 to 1990. A severe economic crisis, social unrest and violence marked his first term. After the default foreign debt and debt crisis of 1983, Peru plunged in a hyperinflationary spiral and saw the onset of insurgency led by two terrorist groups, namely, Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) and the MRTA (Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amarú). By 1990, the country was isolated from the international trade and investment community. During the early 1990s, Fujimori implemented macroeconomic economic reforms that set Peru on a recovery path. He also defeated the two main guerrilla movements that were rampaging Peru amidst a civil war restoring a sense of stability to the nation. His methods were drastic and later will bring him dramatically to his downfall. In 1992, President Fujimori closed Congress to retain control. When Congress was reopened, it approved an unconstitutional third period for the president. During his second term 1995-1999, he pushed aggressive pro-market reforms and conducted the privatization of state owned corporations. His third term ended abruptly in 2000 amidst corruption charges and with President Fujimori resigning to his commission and fleeing to Japan. The president of Congress, Valentín Paniagua, formed government of transition charged with organizing general elections that led to the election of Alejandro Toledo as president of Peru. Alejandro Toledo came to international prominence after leading the opposition against President Alberto Fujimori, who held the presidency from 1990 to 2000. President Alejandro Toledo (2001-2006) pushed aggressively the implementation of pro-market reforms and pushed for regional integration. Alan García won the 2006 elections in a run-off against Union for Peru candidate Ollanta Humala. Unlike his first disastrous presidential term, President Alan García (2006- 2011) continued with the pro-market reforms and regional integration efforts of his two predecessors. During Alan Garcia second term, former President Fujimori was captured in 2005 during a visit to Chile. He was tried, convicted in 2007 for crimes against Humanity, and sentenced to a 25-year prison term. The court also added a 7 and 1/2 year term for embezzlement of state funds.

Remarkably, Figure 1 shows that restaurants speeded-up their multinationalization after the onset of pro-market reforms in 1990. Restaurants that started before 1990 had an average of 12 years of delay from founded to multinationalization. Besides, restaurants that were founded after 1990 had an average of 4 years of delay from founded to multinationalization. The latter restaurants started multinationalization three times faster that the former did. Hence, these findings contradict the gradual internationalization model and support the institutional preposition of internationalization.

Location to start multinationalization

Figure 2 findings are in line with previous research on first FDI of multilatinas (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008). Figure 2 shows the location of the restaurants first FDI. These results are hard to explain by either of the two theoretical model of internationalization. The gradual internationalization proposes that firms expand first to countries with proximate psychic distance, such the Southern region of South America. A cluster of restaurants follows this pattern. However, other group of restaurants follows the opposite pattern by internationalizing first to countries with remote psychic distance such as the US or India. Even if we consider liability of Outsidership instead of psychic distance, it seems apparent that USA and India would score high in Outsidership relative to global network based in Peru. In addition, no apparent location advantage explains both close FDI and distant FDI.

Market integration to start multinationalization

After performing a literal replication of previous findings (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008), we expanded the theory by adding a comparison of other institutional factors, such as market integration with other countries. We include this variable to build support in favor of the institutional proposition of internationalization of multilatinas (Cuervo-Cazurra & Dau, 2009).

An important institutional phenomenon in Latin America was the spread of domestic pro-market policies across the region. Most Latin American countries realized that they had lost a decade or two since the debt crisis of 1983 and launched aggressive regional and global integration trade policies. Consequently, the region joined the world after 1990 on a race towards economic globalization.

From an economic globalization perspective there are two types of market integration: product-market integration and factor-market integration (Ghemawat, 2003). Ghemawat defined product-market-integration as the incomplete integration among countries achieved by global trade, foreign direct investment, and convergence of prices. Factor-market-integration refers to the (uneven) pooling of country's resource endowments such as capital, labor, and knowledge across borders.

We measured the above-mentioned two aspects of market integration (i.e., integration of markets of products, and integration of markets of factors of production) using the following items: trade integration, foreign direct investment integration, price integration, capital integration, labor integration, and knowledge integration. These items are the most relevant measures suggested by the emerging IB literature in globalization (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004; Ghemawat, 2003; Ricart et al., 2004).

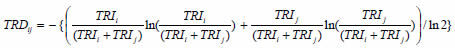

Our measures captured "how similarly countries are integrated to the world" as indicators of market integration between countries. Our market integration measures are based on Balassa's inequality indices. The international trade literature use extensively Balassa's indices (Balassa, 1986; Balassa & Bauwens, 1987; Bergstrand, 1990). The following expression is the similarity index of trade intensity or "Trade integration" (TRD):

Trade-integration between countries (TRDij) is equal to 1 when both countries i and j have equal values of trade intensity (TRDi and TRDj), and TRDij is equal to 0 when trade intensity of one country is very small in comparison to the other. We also calculated each of the items. To calculate FDI integration we used FDI inflows; for Price integration, consumer prices indices; for Capital integration, capital intensity; for Labor integration, wages; and for knowledge integration, average years of higher schooling in the total population.

A recent study of the above-mentioned measures of market integration (Rivas et al., 2006) revealed a slightly different definition from the one proposed by Ghemawat (2003). Rivas et al. (2006) performed a factor analysis between 1970 and 2000 on these items. The authors found that integration of trade and FDI loaded on one factor, whereas integration of prices, capital, wages, and education loaded on a different factor. Based on this insight, we calculated product market integration as the average of measures of trade integration and FDI integration. We calculated factor market integration as the average of measures of integration of prices, capital, wages, and schooling.

We then calculated the product-market and factors-market integration indices for every event of FDI made by Peruvian restaurants. These indices were calculated between Perú and the FDI target country. We had indices available from 1970 to 2000. However, with the exception of two instances, most of the FDI events occurred after 2000. Given this limitation, we used the indices for 2000 for all instances of FDI occurred between 2000 and 2009.

Figure 3 shows that all restaurants started multinationalization to countries with high market integration. The earliest restaurant to internationalize was, in 1989, El Otro Sitio. This restaurant is positioned in high factor-market integration (high integration of prices, capital stock, wages, and schooling). However, it is positioned close to the threshold for low product-market integration (low integration of trade and FDI). This indicates that this restaurant had its first FDI when markets where fairly closed to trade and investment, nevertheless they were similar in other institutional aspects. These findings lend additional support to the institutional proposition of internationalization of multilatinas.

Business level multinationalization strategies

We used a resource based view (RBV) to analyze the impact of business model and multimatinalization. The resource based view states that the resource profile controlled by firms determine their performance (Barney, 1991; Barney, 1996; Penrose, 1959; Wernerfelt, 1984). We classified the business models by using a price versus quality map. The two authors and two research assistansts ranked the top Peruvian restaurants by price and quality. Data for price was obtained from websites and menu cartes obtained for each reataurant. Data for quality was obtained from the "directorio de restaurantes categorizados y calificados", a local directory of restaurants. Once everybody had a chance to review the categories, we discussed the corresponding restaurant positions on the map. In addition, the main authors visited most of the restaurants in the sample to verify the quality classification.

Figure 4 shows four archetypical business models, namely, Low Cost Leadership, Premium Niche, Low Coast Niche, and Stuck in the Middle. The Premium Niche business model represents restaurants that have created culinary innovations fusing or mixing elements of European or Asian food with the traditions of Peruvian cuisine (e.g., Astrid and Gastón). They are higher in price and quality than their competitors are. Low Cost leaders are restaurants that offer a reduced variety of fast food, but at a high quality and similar or lower price than competitors (Bembos). Low Cost Niche restaurants focus on rotisserie chicken at lower price than competitors do. Peruvian rotisserie chicken or "pollo a la brasa" has levels of devotion and national pride among the vast local population. We coded each restaurant with a dummy variable representing each business model.

We propose a RBV hypothesis of internationalization of multilatinas; namely, firms learned and developed organizational capabilities that ultimately improved their effectiveness for competing abroad. The institutional proposition of internationalization assigns the gain in competitiveness, on the reduction in transaction costs for domestic firms due to favorable institutional factors. The RBV proposition assigns such gains to learning, accumulation of assets and unique capabilities. The two propositions are complementary: the institutional framework addresses the overall reduction of transaction costs for all domestic firms, whereas the RBV addresses why there is heterogeneity of performance among domestic firms.

Figure 5 shows the average net revue and growth for each business model (average of companies of our sample), compared to foreign fast food multinationals competing in Peru. Growth for US-MNCs decline gradually whereas growth for Low Cost Leaders and Premium Niche increase gradually over the period. In the last year of the trend (2007), growth of both Premium Niche and Low Cost Leaders were substantially larger than the growth of US fast food MNCs.

These findings lend support to both the institutional proposition of internationalization of multilatinas as well as the RBV proposition. Regarding the institutional proposition, pacification of the insurgency, pro-market reforms, and market integration with countries of the region reduced transaction costs for domestic firms creating the conditions for a rapid growth of domestic companies. Domestic restaurants benefit more from economic globalization that foreign multinational companies competing in Peru. Regarding the RBV proposition, domestic restaurants in the two top performing groups were able to accumulate resources and gain organizational capabilities while perfecting their business models. Low cost leaders benefited the most presumably, because the standardization inherent to such business model accelerated their speed of expansion.

Figure 6 shows a logarithmic scale of number of FDI on the y-axis and net revenues on the x-axis. The logarithmic scale facilitates the visualization of elasticity between FDI and domestic revenues, which is the slope of the trend shown in the logarithmic-scale scatter-plot. The findings suggest that the percentage growth of FDI increases with the percentage growth of domestic revenues. Both revenues and FDI were an order of magnitude larger for Low Cost Leaders than for Premium Niche restaurants. We had incomplete data and could not calculate the trend for Low Cost Niche restaurants.

These findings lend support to both the RBV and the institutional propositions of internationalization of multilatinas. Regarding the institutional proposition, pro-market reforms led to international expansion of domestic firms. Regarding the RBV proposition, different business models with unique organizational capabilities and resource profiles yield different internationalization rates.

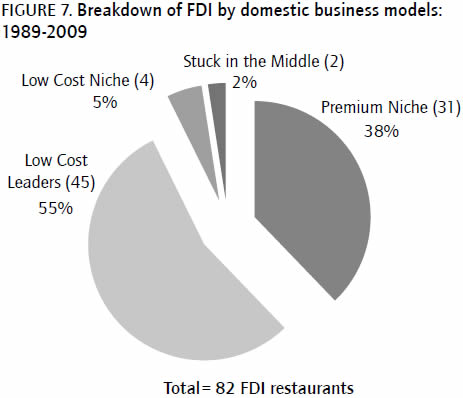

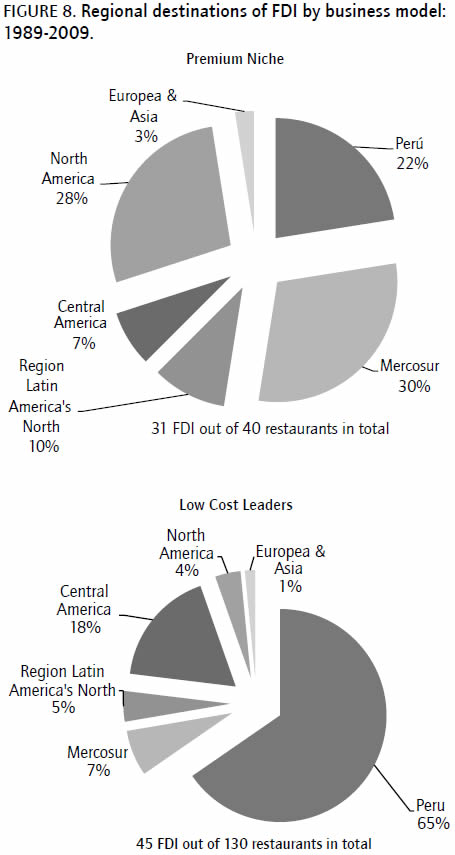

Figure 7 shows the breakdown of FDI by business model over the past two decades. The two dominant business models of multinationalization are Low Cost leaders (55%) and Premium Niche (38%).

Figure 8 reveals each business model has a distinctive and unique multinationalization process. Low Cost leaders focused on Central America, whereas Premium Niche focused both on the Southern region of South America and North America. These findings lend support to the RBV proposition. For instance, Guatemala hosts most of the existing foreign multinational franchises companies. Such a place is an ideal learning ground for Low Cost leader such as Bembos, in their efforts to become a multinational franchise.

Discussion

Received view

To improve the external validity of this study, we replicate the findings of previous research on internationalization of multilatinas (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008). Regarding Time to start multinationalization, we found that multilatinas have a substantial delay between the year funded and the first FDI. However, FDI increased exponentially after the implementation of pro-market reforms in the 1990s. Regarding location to start multinationalization, we found that multilatinas expand to countries with proximate as well to countries with distant psychic distance. These findings are at odds with the gradual internationalization model and the eclectic paradigm, the two predominant theoretical models to explain multinationalization.

Institutional environment to start multinationalization: Pro-market reforms of domestic markets and regional market integration

We found support instead for the institutional propositions of internationalization of multilatinas, namely, that institutional reforms reduced transaction costs for domestic firms, which benefited domestic firms over multinationals competing in the host country. We measured the economic market integration between Perú and the destination country of FDI. These are measures of the spread of institutional reforms in the region and the increasing economic globalization of Latin American countries. We found that all the firms started their first FDI in countries with high market integration; hence, their first FDI was in countries with similarly favorable institutional environments.

Business level multinationalization strategies

We found support for the RBV proposition of internationalization of multilatinas; namely, firms learned and developed organizational capabilities that ultimately improved their effectiveness for competing abroad. The institutional proposition of internationalization explains gains in competitiveness based on the reduction of transaction costs for domestic firms due to institutional reforms. The RBV proposition explains such gains due to learning, accumulation of assets and unique capabilities. The two propositions are complementary: The institutional framework addresses the overall reduction of transaction costs for all domestic firms, whereas the RBV addresses why there is heterogeneity of performance among domestic firms.

The study found three main Peruvian restaurants business strategies namely, premium niche, low cost leader, and low cost niche. Two strategies dominated the Peruvian restaurants industry's multinationalization: premium niche and low cost leaders. The regional destination of FDI varied drastically between these two strategies, where premium niche companies focused on the US and the Southern Cone of South America (Mercosur), whereas lows cost leaders focused on Central America. Premium niche companies created high quality restaurants that introduced products that combined European flavors and Peruvian spices, which captured the imagination of international enthusiasts of the Peruvian cuisine. These restaurants almost simultaneously opened restaurants in neighboring countries (Mercosur) and in the US. These restaurants targeted their FDI to cities in the US with substantial Hispanic markets. Besides, low cost leaders developed fast food franchises that expanded in the local domestic market and became serious competitors of foreign fast food chains. Low cost leaders' pattern of multinationalization was more conservative and sought learning from competitors on high competitive markets. This motive led them to expand to Central America, where there is a substantial presence of foreign fast food franchises.

Conclusion

This study endorses the growing view that there is a need to expand the theorizing on multinationalization of firms from emerging economies. Both institutional model and the Resource based View of the Firm seem promising theories to build a new understanding of multinationalization of firms from emerging economies.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the able research assistance of Claudia Soberón and Sully SiuCho, students at Universidad del Pacífico. This research was possible by support of the Fulbright Commission, the Wehle School of Business from Canisius College, and the Facultad de Administración de la Universidad del Pacífico (Perú). All errors remain ours.

References

AméricaEconomía. (April 2008). Especial multilatinas: Ranking. AméricaEconomía, 26-36. [ Links ]

Aykut, D. & Goldstein, A. (2006). Developing country multinationals: South-south investment comes of age. OECD Papers, 6(13), 1-42. [ Links ]

Balassa, B. (1986). Intra industry trade among exporters of manufactured goods. In D. Greenway & P. K. M. Tharkan (Eds.), Imperfect competition and international trade: The policy aspects of intraindustry trade. Brighton: Wheatsheaf Press. [ Links ]

Balassa, B. & Bauwens, L. (1987). Intra-industry specialization in a multi-country and multi-industry framework. Economic Journal, 97, 923-939. [ Links ]

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. [ Links ]

Barney, J. B. (1996). The resource-based theory of the firm. Organization Science, 7(5), 469-469. [ Links ]

Bergstrand, J. (1990). The heckscher-ohlin-samuelson model, the linder hypothesis and the determinants of bilateral intra-industry trade. The Economic Journal, 100, 1216-1229. [ Links ]

Buckley, P. J. & Ghauri, P. N. (2004). Globalization, economic geography and the strategy of multinational enterprises. (perspective). Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 81-98. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2008). The multinationalization of developing country mnes: The case of multilatinas. Journal of International Management, 14(2), 138-154. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. & Dau, L. A. (2009). Promarket reforms and firm profitability in developing countries. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1348-1368. [ Links ]

da Silva, J. F., da Rocha, A. & Carneiro, J. (2009). The international expansion of firms from emerging markets: Toward a typology of brazilian mnes. Latin American Business Review, 10(2/3), 95-115. [ Links ]

Dunning, J. H. (1979). Explaining changing patterns of international production: In defense of the eclectic theory. Oxford Bulletin of Economics & Statistics, 41(4), 269-295. [ Links ]

Dunning, J. H. (1980). Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies, 11(1), 9-31. [ Links ]

Ghemawat, P. (2003). Semiglobalization and international business strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(2), 138-152. [ Links ]

Guillén, M. F. & García-Canal, E. (2009). The american model of the multinational firm and the "New" Multinationals from emerging economies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(2), 23-35. [ Links ]

Johanson, J. & Vahlne, J.E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm--a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 25-34. [ Links ]

Johanson, J. & Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411-1431. [ Links ]

Maanen, J. V. (Ed.). (1983). Qualitative methodology. (An updated reprint of the december 1979 issue of administrative science quarterly). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Martinez, A., De Souza, I. & Liu, F. (2003). Multinationals vs. Multilatinas: Latin America's great race. Strategy + Business, (Fall), 1-12. [ Links ]

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1984 [1990]). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. London: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Ricart, J. E., Enright, M. J., Ghemawat, P., Hart, S. L., & Khanna, T. (2004). New frontiers in international strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(3), 175-200. [ Links ]

Rivas, R. M., Rakovski, C. C. & Skaletsky, M. (2006). Bilateral measures of globalization 1970-2000. Eruditio de Commercio, Richard J. Wehle School of Business Working Papers Series, WP 2006-01, 1-27. [ Links ]

Santiso, J. (2007). The emergence of multilatinas. In Current issues: Latin America. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Deutsche Bank Research. [ Links ]

Santiso, J. (Agosto 2008). La emergencia de las multilatinas. Revista de la CEPAL, 95, 7-30. [ Links ]

Toledo, R. (2008). The rise of the multilatinas. PM Network, 22(9), 28-29. [ Links ]

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: Design and methods (volume 5). Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]