Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Innovar

Print version ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar vol.21 no.42 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2011

Claudia Mellado* & Claudia Lagos**

Associate professor at the School of Journalism, University of Santiago (Chile). Prof. Mellado completed her Ph.D. at the Pontificia Universidad de Salamanca, Spain. During 2007-2008 she did her postdoctoral work at School of Journalism, Indiana University. E-mail: claudia.mellado@usach.cl

Assistant professor at the School of Journalism, University of Chile (Chile). Prof. Lagos completed her master degree at the University of Chile, Chile. E-mail: cllagos@uchile.cl

Submitted: January 2011 Accepted: August 2011

Abstract :

On the basis of survey responses of 570 journalists from 114 newspapers, radio, newswires, television, and internet news organizations, this paper describes the role conceptions, epistemological underpinning, and ethical values of the Chilean news media workers, comparing the differences that exist among media types and between the capital and the rest of the country. The findings show territorial cultures of journalism, with differences between the capital and provincial regions, mostly classifiable, because of the country's centralization and sociocultural characteristics. Likewise, the results indicate that the Chilean journalists' professional culture is not a substantial function of the type of media in which they work, and that the effects that "region" and "media type" factors have on journalism culture are independent from each other.

Keywords:

Journalism cultures, institutional roles, epistemological orientations, ethical values, journalists, Chile.

Resumen:

A través de una encuesta online aplicada a una muestra representativa de periodistas provenientes de 114 periódicos, radios, agencias de noticias, televisión e Internet, este artículo describe los roles profesionales, las orientaciones epistemológicas y los valores éticos de los periodistas chilenos, comparando las diferencias que existen en los ámbitos organizacional y geopolítico. Los resultados muestran culturas territoriales de periodismo, mayormente clasificables como producto de la centralización del país y sus características socioculturales. Asimismo, los resultados indican que la cultura profesional de los periodistas no es una función substancial del tipo de medio en el cual ellos trabajan, y que el efecto que tienen los factores "región" y el "tipo de medio" sobre la cultura de periodismo son independientes el uno del otro.

Palabras clave:

culturas de periodismo, roles institucionales, orientaciones epistemológicas, valores éticos, periodistas, Chile.

Résumé :

Au moyen d'une enquête appliquée sur un échantillon représentatif de journalistes provenant de 114 journaux, radios, agences d'information, télévision et Internet, cet article décrit les rôles professionnels, les orientations épistémologiques et les valeurs éthiques des journalistes chiliens, comparant les différences qui existent au niveau organisationnel y géopolitique. Les résultats montrent des cultures territoriales de journalisme, principalement classifiables, produit de la centralisation du pays et leurs caractéristiques socioculturelles. De plus, les résultats indiquent que la culture professionnelle des journalistes n'est pas en rapport substantiel avec le genre de media dans lequel ils travaillent, et que l'effet du facteur "région" et du facteur "genre de media" sur la culture de journalisme est indépendant.

Mots-clefs :

cultures de journalisme, rôles institutionnels, orientations épistémologiques, valeurs éthiques, journalistes, Chili.

Resumo:

Através de uma enquete online aplicada a uma amostra representativa de jornalistas provenientes de 114 periódicos, rádios, agências de notícias, televisão e Internet, este artigo descreve os papéis profissionais, as orientações epistemológicas e os valores éticos dos periodistas chilenos, comparando as diferenças que existem em nível organizacional e geopolítico. Os resultados mostram culturas territoriais de jornalismo, principalmente classificáveis produto da centralização do país e suas características sócio-culturais. Da mesma forma, os resultados indicam que a cultura profissional dos jornalistas não é uma função substancial do tipo de meio no qual eles trabalham, e que o efeito que têm os fatores "região" e o "tipo de meio" sobre a cultura de jornalismo, são independentes um do outro.

Palavras chave:

culturas de periodismo, papéis institucionais, orientações epistemológicas, valores éticos, jornalistas, Chile.

As journalism has become one of the most important institutions for understanding the political, economic and cultural processes of democratic societies (Cook, 1998), scholars have not only had to focus on the study of what is news for the media, but also understand how news content is developed, in which context and under which professional cultures (Mellado, 2009).

In the image of professional journalism, there are five ideal values that have given legitimacy and credibility to the activity throughout decades: Public service, objectivity, autonomy, immediacy and ethics (Deuze, 2005). However, many of these values have been put into doubt, challenged all of them by new technology, as well as the global economy and politics (Christians et al., 2009).

Specifically in Chile, since the beginning of the 1990s, journalism has faced different structural and productive changes. After 17 years of dictatorship, the press has had to gradually recover its freedom, losing the fear it had gotten used to under military repression. In turn, the consolidation of the free market, as well as the incorporation of new technology into everyday life, have driven the appearance of new platforms of social interaction, forcing the traditional media to increase their scope and reconsider their relationship with the audiences.

But although on a global scale Chile is a democratic country with relatively strong levels of freedom of speech (Freedom House, 2009), neither this freedom- established by the Constitution-nor democracy guarantee that the media will move forward in the promotion and defense of public interest.

The concentration of media ownership (Becerra and Mastrini, 2009), as well as their political-ideological interests (Mönckeberg, 2009), have been strongly associated to low levels of pluralism in the news, homogenization of the agenda, a condescending attitude towards official powers, and the journalists' loss of power as independent professionals (Dermota, 2002; Gronemeyer, 2002; Santander, 2007).

In the case of the press, the country faces a duopoly structure made up of the El Mercurio and Copesa, both strongly linked to the country's political right. Television is a mix of public and private undertakings. The national television networks include the public TV station Televisión Nacional de Chile (TVN); the Canal 13, that used to belong to the Catholic Church, today is in hands of the Luksic group; Megavisión, a private channel owned by the Claro group and the Mexican consortium Televisa; Chilevisión, owned by Time Warner; and La Red, which is owned by the Mexican businessman Ángel González.

Radio is dominated by a small number of consortiums, such as the Spanish Prisa group and the Grupo Dial, which belongs to Copesa. Among the national networks, the Cooperativa and Radio Bío-Bío networks stand out, owning 48 and 51 radio stations, respectively. The Bío-Bío group also controls a regional television channel, and is associated with CNN Chile, a cable news TV station.

This current state of journalism is rooted in its origin and development. The first impulses made by the press after Chile's Independence (1810) were timid and irregular. Only at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century did the press attain a new vigor, thanks to its relationship with the so-called "social question".

Many newspapers came about during the political struggle, from the mancomunales (unions formed by leftist workers, very common at the end oh the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries), as well as from the more conservative sectors. During this time, the more professional press was born, looking more like what we today understand as a newspaper. On of the first examples was El Ferrocarril, which disappeared with the new century, and later, El Mercurio, which is still in circulation. At that time, the popular press also began to appear, consolidated in the second half of the 20th century with El Clarín, which had an enormous circulation until its closure with the Military coup in 1973.

After the coup, newspapers, magazines, and radio stations were shut down, and television stations were intervened. This period was characterized by censorship and self-censorship. Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, independent journalistic projects began to appear, pushing the limits and imposing topic and points of view that until that time had been silenced. That press, key in recovering democracy, slowly disappeared during the 1990s because of lack of financing, among other reasons (Dermota, 2002). Since then, the practice of journalism has experienced two relevant phenomena: The first is its sensationalism, where the agenda has been predominantly focused on television; and the second, the circulation, readership and public investment crisis, especially in the press, which has been also experienced in the rest of the world. In this context, professional projection, as well as the work conditions of those who work in written press, television and radio have been very uneven (Mellado, 2011).

Meanwhile, although regionalization has become a priority topic in the re-democratization process of the social and political system, the country is still marked for its high level of centralization in decision making and marginal participation of its regions (PNUD, 2009). Chile is divided into 15 regions. Santiago, the capital, is located in the Metropolitana Region, and contains more than 40% of the nation's population. All of the media with national coverage are located in the capital, as well as the government and the corporate offices of the majority of companies operating in the country -both national and international. Only the legislative power is located in another region, 120 kilometers west of Santiago.

Despite all of these circumstances, scholars have not made systematic efforts to study the Chilean journalists' professional cultures. Considering this shortcoming, the objective of this study is to map the different domains that outline both organizational and territorial journalism culture among Chilean news media workers.

Journalism culture, as a concept of inquiry, has gained space in the global academic circuit, especially because of its capacity to integrate the journalists' diversity of professional norms, orientations and practices under one concept, in a more intuitive and orderly manner (Hanitzsch, 2007). Authors like Schudson (2001), Deuze (2002), Campbell (2004), and Zelizer (2005), among many others, have used the concept of journalism culture to address the identity of journalism around the globe.

However, most of the empirical research comes from Western countries and has been limited to studying specific aspects within the phenomenon (Weaver and Wilhoit, 1986, 1996; Weaver et al., 2007, Patterson and Donsbach, 1996; Berkowitz et al., 2004; Cuillier, 2009; Ettema and Glasser, 1984; Donsbach and Klett, 1993, among others).

In Latin America, and specifically in Chile, the scarce research on journalists has been linked to the study of their sociodemographic, work, and educative profile, and very little has been done on the analysis of the ways journalists make sense of their work and profession (Mellado, 2010). One of the studies that can be classified within the last orientation was developed by Wilke (1998), who carried out a comparative analysis among Chilean, Mexican and Ecuadorian journalists. In the Chilean case, Wilke describes the journalists as "neutral" reporters and "public entertainers". At the beginning of the 21st century, Gronemeyer (2002) analyzed the Chilean journalist's autonomy and levels of independence, based on a survey applied to reporters and editors. The study found that both groups gave great importance to characteristics like veracity, critical thought, and independence within the practice of journalism.

Mapping journalism culture

With the objective of integrating the different approaches used by scholars to study journalism culture, Hanitzsch (2007) suggested a heuristic model -designed to identify areas of disagreement among journalists regarding their attitudes, beliefs and role conceptions.

Specifically, the model argues that there are three central domains in which journalism cultures materialize: The first domain is institutional roles -also called journalistic or media roles-and refers to the normative and real functions of journalism in society; a set of expectations, values, norms, and standards defining how news people and organizations should and do work (Norris and Odugbemi, 2008, p. 28). The second domain is epistemological orientations, and deals with the justification of knowledge and the validity criterion used by journalists to distinguish what is true from what is false. Finally, ethical values point to the question of how journalists respond to ethical dilemmas.

The model recognizes the existence of three fundamental divisions when measuring institutional roles (interventionism, power distance and market orientation), two relevant aspects within the epistemologies orientation domain (objectivism and empiricism), and two fundamental categories within the ethical values domain (relativism and idealism). Each one of these divisions spans two ideal-typical poles, along a continuum.

Interventionism reflects the extent to which journalists follow a particular mission and promote certain values. The distinction is made between two types of journalists: one active, socially committed, and the other passive and distant. The level of power distance refers to the journalist's position towards loci of power in society. The adversary pole of the continuum captures a type of journalism that denounces wrongdoings and challenges those in power. The 'loyal and opportunist' journalism, on the other hand, tends to defend authorities, and serves as a messenger for the political and economic elite. Market orientation accounts for the journalists' viewpoint of the audience as either citizens or consumers. In the latter perspective, journalism cultures strongly submit to the market logic -consumer oriented approach- as opposed to the citizen oriented approach, that gives priority to what journalists think the public should know.

The objectivism dimension marks the distinction between two fundamental beliefs: The existence of a truth that can be portrayed 'just as it is', and the belief that news is just a representation of the world that requires interpretation. Empiricism refers to the relative weight given to an empirical justification of truth. Journalism cultures close to the active pole of the continuum emphasize observation, measurement and experience, while the journalism closer to the pasive pole accentuates reason, opinion, and analysis.

Relativism refers to the way in which journalists confront ethical decisions. While some base their personal moral philosophies on universal ethical rules, others believe that ethical decisions are very dependent on the situational context. Finally, the idealism dimension measures the importance that journalists give to the consequences of their actions, when they deal with ethical dilemmas. While some journalists are more means-oriented and believe that desirable consequences should always be obtained with the 'right' action, others are more goal-oriented and admit that harm will sometimes be necessary to produce a greater public good.

Through the Worlds of Journalism project (2008-2009), the model was used to describe journalism cultures in 18 countries, among them Chile (Hanitzsch et al., 2011; Mellado et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the project's design was originally planned for cross-national comparison, and not analyzing the differences and similarities that could take place within each one of the countries, even though variances within cultures may sometimes be greater than variations across cultural boundaries (Øyen, 1990). Also, it used non-probabilistic/matched samples of 100 journalists per country: Each one of the samples were similar in terms of their internal structure-allowing for comparison across countries (Hofstede, 2001)-but it is difficult to generalize the results, and limit the statistical possibilities to the analysis of just one nation.

This work uses the general conceptualization proposed by Hanitzsch, but will go into depth on the organizational and territorial variations of journalism culture within a single country, using a representative sample of Chilean news media workers.

Although Hanitzsch's model mentions the existence of "dimensions", the way that the items are measured in the survey designed for these purposes-on the basis of positive and negative statements within each dimension-makes any statistical analysis tend to treat both poles on the continuum as different factors, without possibility of reliably testing the model's statistical validity. Because of this, and considering that our study uses the survey designed by Worlds of Journalism project as a baseline, no reference will be made to dimensions, rather to divisions or relevant concepts, with a mainly descriptive goal within each analyzed domain.

RQ1: How do Chilean news workers evaluate journalism's institutional roles, epistemological orientations and ethical values?

RQ2: How do different news media types shape Chilean journalists's role perceptions, epistemological orientations and ethical values?

RQ3: How does the capital region differ from the provincial regions in terms of journalists' role perceptions, epistemological orientations and ethical values?

RQ4: Is there any effect of the interaction between media type and region, in the way journalists evaluate their professional culture?

Research design and population

The data reported in this article comes from an on-line survey of Chilean news media people conducted in the Antofagasta, Biobío, Araucanía, and Metropolitana regions. These territorial zones represent the north, center, and south of Chile, as well as 70% of the nation's population.

Following Weaver and Wilhoit's classic definition (1986, p. 168), a news media journalist was considered as someone who has "editorial responsibility for the preparation or transmission of news stories or other information [...] rather than those who created fiction, drama, art, or other media content". The sampling population comprised not only full-time, but also part-time news media people who worked for any daily and weekly newspapers, news magazines, radio stations, television channels, newswires and professional Internet media. Journalists surveyed included reporters, news writers, commentators, columnists, copy editors, editors, publishers, news anchors and producers of news. Photographers and cameramen were excluded, as were graphic designers, librarians, and audio technicians because they do not usually have direct responsibility for news content.

Data collection

The self-administered questionnaire was distributed to the entire journalist population under study (N=1979). The emails addresses, as well as the population's basic parameters, were available because of the first census of Chilean journalists and journalism educators carried out between August 2008 and April 2009, in the frame of the larger research project to which this study belongs (Mellado et al., 2010).

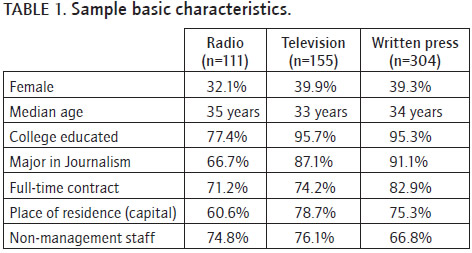

The online survey was carried out during a 5-week period in the Chilean spring of 2009 (November-December). The research team invited the population to participate in the study. Four days later, the survey link was sent to the email of each journalist, instructing them to respond to the questionnaire at the time of their convenience by using any computer with Internet access. Before beginning with the questions, the surveyed were asked to give their informed consent by clicking on a particular button on their computer screen. The survey's instructions established that in the case of having more than one job, journalists should answer considering their most important workplace, so the response rate could be monitored through the census's database. After four follow-up email reminders, a total of 570 usable surveys were completed, yielding a response rate of 29% (See Table 1). Although this percentage is low, it is slightly higher than those obtained by other on-line surveys (Kwak and Radler, 2002).

With the objective of controlling non-response error, sociodemographic, geographical and work related variables -sex, age, level of education, place of residence, media type, and full-time/part-time contract- were checked against the results of the census. According to the analysis, respondents and non-respondents were quite homogeneous, with no significant differences among the groups in terms of gender, education level, media type, or full-time/part-time positions. The age variable presented significant differences between the sample and the population, but only in the 31-35 age group. Another significant difference was observed in the sample's geographic distribution. Although the representation of journalists from Santiago was almost perfect, journalists from the Biobío and Araucanía regions were slightly over-represented, while journalists from the Antofagasta Region were underrepresented. During the analysis, the totals from the three provincial regions were combined, as no significant differences were observed between them.

Measurement

The set of scales used for this study was adapted to the three domains proposed by Hanitzsh (2007) and operationalized by Worlds of Journalism project (2007-2009). Specifically, when designing the items that measure institutional roles, work by Weaver and Wilhoit (1986, 1996), Weaver et al. (2007), and Ramaprasad and Kelly (2003) was also used. Nevertheless, due to cultural and social characteristics specific to Chile, some of the questions were eliminated, others were added, and still others were reworded, in order to explore important local issues. Twenty eight items were asked in order to measure the journalist's selfperceptions regarding the importance of different institutional roles, on a 5-point scale where one corresponded to "not important at all", and five corresponded to "extremely important". In the case of epistemological beliefs and ethical values, eight and six items were used to measure the journalists' agreement or disagreement, respectively, on a 5-point scale where the response options were from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree".

In order to answer the research's questions of this study, a general characterization of the three culture domains among Chilean journalists is described by means of scores and standard deviations of the journalists' responses.

Differences according to media type (written press, radio and television) and geographic location (region/capital), as well as possibles interaction terms between them, were calculated through analysis of variance.

For reasons of parsimony, and because of the small sample size that on-line newspaper, news agency and magazine journalists represent, they were grouped together with newspaper journalists in the written press category.

Different statistical tests were previously done in order to investigate possible discrepancies inside this group, and no significant differences were found in any of the measured items.

Institutional roles

Regarding the level of interventionism, the results show that the classic professional values of detachment and noninvolvement are not very important characteristics of Chilean journalism. This pattern is consistent with the three media types under study, with no significant differences found between the capital and the provincial regions, nor important effects of interaction between the variables (see Table 2).

Chilean journalists tend to favor a more committed stance with society, ranking high in most of the items corresponding to the active pole of the division. The data show significant differences among media type and region, although non significant interaction term between both factors.

Television journalists significantly differ from radio journalists, and give more support to influencing public opinion (F=4.075, d.f=2; p<.05). Written press journalists move away from radio journalists and television journalists, caring less for cultivating patriotism and nationalism (F=8.176, d.f=2; p<.001).

Meanwhile, promoting ethical or moral values (F=26.138, d.f=1; p<.001), and cultivating nationalism and patriotism (F=70.705, d.f=1; p<.001), are functions more valued by journalists from the provincial regions than from the capital -the latter able to explain 11.4% of the overall variance. This result could be related to the cultural characteristics that differentiate the capital with the rest of the country. Provincial cities are much smaller than Santiago, and they tend to have a more conservative and traditional population. A good part of the production and consumption of cultural goods and services is concentrated in the capital. In this vein, this finding may reflect a strategy for the construction of regional identity as opposed to the metropolitan/central identity.

In terms of power distance, journalists were found to be supportive of "acting as a watchdog" of the facto powers, although significant differences are observed among journalists from the provincial regions and those from the capital, the latter giving less importance to the vigilance of the citizens (F=20.969, d.f=1; p<.001) (see Table 3).

The country's high centralization causes the capital to be the place where the economic and political power is concentrated, as well as its cultural production. This situation could generate more opportunities for keeping watch on the facto powers among the journalists who work there. In addition, the same powers being "watched" have made their impact on public space more professional (Tironi and Cavallo, 2001) having communication teams, generally located in the capital, with the purpose of facilitate their influence in the media's agenda. The regional press, meanwhile, has a more limited agenda of official news, forcing it to develop its own news guideline, more focused on its citizens.

According to region, there are no significant differences, nor important interaction effects among the variables.

On the other pole of the continuum, Chilean journalists tend to reject the functions linked to the propagandistic role. The items that measure this position are the worst evaluated within the domain of institutional roles, especially by journalists from the capital, give greater support to highlighting the country's advances and triumphs in relation to the rest of the world (F=33.525, d.f=1; p<.001); actively support government policy on national development (F=9.530, d.f=1; p<.01); highlight the benefits of the current economic model (F=14.121, d.f=1; p<.001); convey a positive image of political leadership (F=9.485, d.f=1; p<.01); and convey a positive image of business leadership (F=30.736, d.f=1; p<.001). Again, the country's centralization may have something to do with this result. Journalists from the regions have less access to the information and the circles of power, making it more difficult for them to challenge official sources and generate their own informative agendas. Likewise, the local press tends to have a closer relationship with regional authorities, because of the small size of the cities and their populations.

Within media types, meanwhile, there are no significant differences, nor are important effects of interaction among the variables.

The functions that measure the both poles of market orientation received the highest percentages of acceptance and mean scores, showed a convergence of functions where important support is given to the press's civic role, as well as the individual needs of the public.

Specifically, the items that were associated with a citizen- orientation caused a transversal agreement among television, radio, and written press journalists. However, journalists from the provincial regions give significantly more importance to providing information that public needs to make political decisions (F=4.913, d.f=1; p<.05), motivate participation in civic activities (F=10.303, d.f=1; p<.001), promote social changes (.F=6.371, d.f=1; p<.05), and assure coverage of local news (F=105. 535, d.f=1; p<.001). Cross-regional differences in this last item are the most important of all of the functions analyzed, accounting for 20% of the overall variance. One reason might be the simple fact that "local news" for media in the capital is actually national news, because of the country's geopolitical centralization. In this sense, it is possible to think that the territorial proximity to national news sources makes them consider it as local, even when they are dealing with aspects of national interest (see Table 4).

A similar situation occurs with the functions more oriented towards the public as a consumer, where journalists from the provincial regions give significantly more importance to helping people with their everyday problems (F= 12.433; d.f=1; p<.001), providing information quickly (F=5.742, d.f=1; p<.00), and producing news that interests a larger number of people (F=11. 667, d.f=1; p<.000), than journalists in the capital. It is not surprising that regional journalists are more concerned with their specific audience's needs, because of Chile's territorial structure. However, considering that audience's ratings have become an important topic in the media's editorial decisions, and also that it has only been institutionalized in the country's capital, it is noteworthy that journalists who work there give less importance to reaching larger audiences. A possible explanation has to do with the greater segmentation that gradually capital media have had in terms of its target audience, in comparison with the more general offer observed in the regional press.

Again, the data does not reveal any significant interaction between media type and region, regarding the level of importance the journalists give both poles of the market orientation approach.

Epistemological orientations

In general, the Chilean journalists tend to disapprove subjectivity in journalism, supporting the study done by Wilke (1998) more than a decade ago in Chile. They consider that impartiality should be a norm, and that their beliefs and convictions cannot influence their reporting.

Levels of empiricism in news making are also a largely valued element by the Chilean professionals, who mostly support the factualness and reliability of information, as well as the separation of facts and opinion.

In territorial terms, significant differences are observed in the positive poles of both epistemological orientations, as can be seen in tables 5 and 6. Journalists from the capital claim greater impartiality (F=13.313, d.f=1; p<.000) and neutrality (F=10.056, d.f=1; p<.01), and agree with separating their personal beliefs from their everyday work (F=14.839, d.f=1; p<.000), more than journalists in provincial regions. At the same time, they give greater support to the use of empirical evidence as a way of facing the news (F=8.327, d.f=1; p<.01) and the idea that the facts speak for themselves (F=7.009, d.f=1; p<.01). It is possible that the differences are partially caused by greater levels of professionalization that exist among journalists working in capital media. Likewise, it is also possible that the capital media outlets' greater competence motivates stronger demands regarding the press's normative standards.

According to media type, significant differences are seen on the other pole of both orientations. Radio journalists claim to be more subjective than written press and television journalists, in terms of making it clear which of the parties in a dispute is right (F=3.625, d.f=2; p<.05). Also, radio journalists tend to create more news content based on their reasoning and analysis, and not through empirical evidence (F=3.750, d.f=2; p<.05). In this last item, an interaction effect can be observed among the variables, indicating that while differences are observed between radio and written press in the capital, in provincial regions they appear between radio and television journalists (F=3.483, d.f.=2; p=.05). According to this result, the journalism that is farthest away from the negative pole of empiricism is developed by the written press in the capital, and television journalists in the provincial regions (see Table 6). Regional journalists that work in television are often correspondents from national channels, and therefore, are influenced by the guidelines and interests of the media located in the capital.

Ethical values

Chilean journalists do not give much support to formulating their own codes of conduct. On the contrary, they strongly defend the existence of universal ethical principles that should be followed regardless the situation and context. This position is not very different among journalists from the written press, radio, and television, although the professionals from the provincial regions are those who give more support to the possibility of reasoning what is ethical or not in determined contexts (F=5.820, d.f=1; p<.05). The small amount of variance explained (1%), however, supports the idea of general consensus regarding the journalists' stance of this aspect (see Table 7).

In terms of levels of idealism, neither percentages of agreement nor the general average of the scores show a clear tendency regarding the importance that journalists give to the active and passive pole of this division. The majority agree with rejecting any questionable reporting method, even if this means not getting the story, but they also tend to support the idea that facing certain situations the damage could be justifiable if the results produce a greater good.

Although no important interaction effects between media type and region were detected, the specific analysis of differences among the groups gives a clearer interpretation of the data (see Table 8). Radio journalists give significantly more support to avoid questionable methods of reporting (F=3.459, d.f=2; p<.05.), and to the idea that reporting and publishing a story that can potentially harm others is always wrong (F=3.628, d.f=2; p<.05). Meanwhile, journalists working in provincial regions are those who give significantly more importance to both aspects (F=7.386, d.f=1; p<.01, for avoid questionable methods of reporting, and F=5.335, d.f=1; p<.05, for harm others is always wrong).

The data, however, appear to be only slightly conclusive and indicate the need for going into depth on more personal factors that identify the journalists, especially if we consider that the journalist's media type and region of origin can only explain 4% of the total variance. Even so, it is possible to venture some elements that could explain this result. The process of news making in capital media, especially television, is based on a highly competitive environment. In provincial regions, in contrast, the competition is less pronounced. In many of their cities there is only one newspaper with regional circulation, and one or a few television channels.

This work described the journalists' roles conception, their epistemological stance towards the search for truth, and their ethical values, with the purpose of understanding the relationship that exists between media type, the geopolitical factor (central/periphery) and journalism culture. The country's high centralization, as well as the particular characteristics and constraints of news reporting that differentiate Chilean media, caused us to suspect a possible clash of cultures among Chilean news media journalists.

In general terms, Chilean journalists distance themselves from the classic professional values of detachment and non-involvement, having a greater proximity with the functions of interpreter, participator and intervener. Likewise, journalists give a strong support to the adversary role, and generally reject positions that are loyal to power. This last result, however, causes certain contradictions considering the current media system in Chile, where a large part of the media outlets (national and regional) are in hands of the political-economic elite. Since the study is based on the journalists' perceptions and not on their real practice, future studies should design methodological strategies able to model not only the perceived journalism cultures, but also those assumed by national and international journalism.

Regarding the way that journalists address their audience, the results showed an important support of the civic role of the press, but at the same time, to the consumer-oriented approach. Indeed, functions coming from both poles end up being the best evaluated. The question that emerges is if the conception of the public as a consumer has become more important because of the productive and structural changes that Chilean media have gone through in the last decades, or if this function has always been present in the journalists' ideology. The lack of national studies hinders a reliable answer to this question, although the first suspect appears to have greater support, since corporate values are becoming more and more important to editorial process.

Parallel to this, the epistemological orientations of the Chilean journalist crystallize in low levels of subjectivism and general high levels of empiricism, while in terms of ethical values, a high consensus exists in terms of general behavior norms that should be followed, although there is less clarity regarding the levels of idealism present in the national press.

Specifically, although the amount of variance that can be explained by the geopolitical factor is only moderate, the results of this study indicate that there are different territorial cultures of journalism, mostly classifiable, because of the country's centralization and sociocultural characteristics.

Another relevant finding of this work indicates that the Chilean journalists' professional culture is not a function of the media type. In fact, very few differences are detected among the institutional roles, epistemological orientations, and ethical values of journalists from the written press, radio, and television. One possibility is that the globalization process, media ownership concentration, as well as a more pronounced newsroom convergence are homogenizing the journalists' ideologies, beliefs and attitudes (Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Deuze, 2007). Another option, however, is that media culture is more linked to job routines, the journalist's socialization in the newsroom, specific editorial structures, and systemic/cross-national variables -regardless of the media type they deal with.

The last result of this study is related to the high independence found between "territorial" and "organizational" factors, in terms of the effect that both produce on Chilean journalism culture. The only significant interaction was concerned with the press's level of empiricism. This finding indicates that the significant differences seen between journalists from the peripheral regions and the capital do not depend, at least on an added level, on media type. Likewise, they show that the strength of the differences existing between the different media types analyzed does not significantly depend of the regional level.

[1] Research for this paper received funding from FONDE CYT Grant No. 1080066.

Becerra, M. & Mastrini, G. (2009). Los dueños de la palabra. Acceso, estructura y concentración de los medios en la América Latina del siglo XXI. Buenos Aires: Editorial Prometeo. [ Links ]

Berkowitz, D., Limor, Y. & Singer, J. (2004). A cross-cultural look at serving the public interest: American and Israeli journalists consider ethical scenarios. Journalism, 5(2), 159-181. [ Links ]

Campbell, V. (2004). Information age journalism. Journalism in an international context. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Christians, C., Glasser, T., McQuail, D., Nordenstreng, K. & White, R. (2009). Normative theories of the media. Journalism in democratic societies. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Cook, T. (1998). Governing with the news: The news media as a political institution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Cuillier, D. (2009). Mortality morality: Effect of death thoughts on journalism students' attitudes toward relativism, idealism, and ethics. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 24(4), 40-58. [ Links ]

Dermota, K. (2002). Chile inédito: el periodismo bajo democracia. Santiago: Ediciones B. [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2002). National news cultures: A comparison of Dutch, German, British, Australian and U.S. journalists. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(1), 134-149. [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2005). What is journalism? Professional identity and ideology of journalists reconsidered. Journalism, 6(4), 442-464. [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2007). Media work. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Donsbach, W. & Klett, B. (1993). Subjective objectivity: How journalists in four countries define a key term of their profession. Gazette, 51(1), 53-83. [ Links ]

Ettema, J. & Glasser, T. (1984). On the epistemology of investigative journalism. Paper presented at the 67th Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Florida (United States). [ Links ]

Freedom House. (2009). Annual survey of press freedom 2009. Retrived from http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=16. [ Links ]

Gronemeyer, M. E. (2002). Periodistas chilenos: el reto de formar profesionales autónomos e independientes. Cuadernos de Información, 15, 53-70. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hanitzsch, T. (2007). Deconstructing journalism culture: Towards a universal theory. Communication Theory, 17(4), 367-385. [ Links ]

Hanitzsch, T., Hanusch, F., Mellado, C., et al. (2011). Mapping journalism cultures across nations: A comparative study of 18 countries. Journalism Studies, 12(3), 273-293. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences. Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Kwak, N. & Radler, B. (2002). A comparison between mail and web surveys: Response pattern, respondent profile, and data quality. Journal of Official Statistics, 18(2), 257-274. [ Links ]

Mellado, C. (2009). Periodismo en Latinoamérica: revisión histórica y propuesta de un modelo de análisis. Comunicar, 33, 193-201. [ Links ]

Mellado, C. (2010). Análisis estructural de la investigación empírica sobre el periodista latinoamericano. Comunicación y Sociedad, 13, 125-147. [ Links ]

Mellado, C. (2012). The Chilean journalist. In D. Weaver & L. Wilnat (eds.), The global journalist in the 21st century: News people around the world. New York: Routledge (in press). [ Links ]

Mellado, C., Moreira, S., Lagos, C. & Hernández, M. E. (2012). Comparing journalism cultures in Latin America: The case of Chile, Brazil and Mexico. Gazette (accepted for publication). [ Links ]

Mellado, C., Salinas, P., Del Valle, C. & González, G. (2010). Mercado laboral y perfil del periodista y educador de periodismo en Chile: estudio comparativo de las regiones de Antofagasta, Biobío, Araucanía y Metropolitana. Cuadernos de información, 26(1), 45-64. [ Links ]

Mönckeberg, M. (2009). Los magnates de la prensa. Concentración de los medios de comunicación en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Random House Mondadori. [ Links ]

Norris, P. & Odugbemi, S. (2008, May). The roles of the news media in the governance agenda: Watch-dogs, agenda-setters. Paper presented at the Harvard-World Bank Workshop The roles of the news media in the Governance Reform Agenda, Cambrigde, MA. [ Links ]

Øyen, E. (1990). Comparative methodology: Theory and practice in international social research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Patterson, T. & Donsbach, W. (1996). News decisions: Journalists as partisan actors. Political Communication, 13(4), 455-468. [ Links ]

PNUD. (2009). Desarrollo humano en Chile. Santiago: PNUD. [ Links ]

Ramaprasad, J. & Kelly, J. (2003). Reporting the news from the world's rooftop: A survey of Nepalese journalists. International Communication Gazette, 65(3), 291-315. [ Links ]

Santander, P. (2007). Medios en Chile 2002-2005. Entre la lucha por el poder y la sumisión al espectáculo. In P. Santander (ed.). Los medios en chile: voces y contextos (pp. 11-37). Valparaíso: Ediciones Universitarias, PUCV. [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (2001). The objectivity norm in American journalism. Journalism, 2(2), 149-170. [ Links ]

Tironi, E. & Cavallo, A. (2001). Comunicación estratégica. Santiago: Taurus. [ Links ]

Weaver, D. & Wilhoit, C. (1986). The American journalist. A portrait of U.S. news people and their work. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Weaver, D. & Wilhoit, C. (1996). The American journalist in the 1990s: U.S. news people and the end of an era. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Weaver, D., Beam, R., Brownlee, B., Voakes, P. & Wilhoit, C. (2007). The American Journalist in the 21st Century: U.S. news people at the dawn of a new millenium. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Wilke, J. (1998). Journalists in Chile, Ecuador and México. In D. Weaver (ed.), The global journalist (pp. 433-452). New Jersey: Hampton Press. [ Links ]

Zelizer, B. (2005). The culture of journalism. In J. Curran & M. Gurevitch (eds.), Mass media and society (pp. 198-214). London: Arnold. [ Links ]