Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Innovar

Print version ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar vol.24 no.53 Bogotá July/Sept. 2014

https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v24n53.43944

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v24n53.43944

The impact of a Paternalistic Style of Management and Delegation of Authority on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Chile and the US

El impacto de un estilo gerencial paternalista y de la delegación de autoridad sobre la satisfacción laboral y el compromiso organizacional en Chile y los EE.UU.

L'impact d'un style de gérance paternaliste et de la délégation d'autorité sur la satisfaction professionnelle et l'engagement organisationnel au chili et aux états-unis.

O Impacto De Um Estilo Gerencial Paternalista E Da Delegação De Autoridade Sobre A Satisfação Trabalhista E O Compromisso Organizacional No Chile E Nos Estados Unidos

Leonardo LibermanI

I PIID, associate professor at the Business Faculty at Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile. E-mail: leonardo.liberman@gmail.com

Correspondencia Universidad de los andes, Mons Álvaro del Portillo 12455, las Condes, santiago (Chile).

Citación: Überman, L (2014). the impact of a Paternalistic style of management and delegation of authority on Job satisfaction and organizational Commitment in Chile and the Us. Innovar, 24(53), 187-196.

Clasificación Jel: M16.

Recibido: agosto 2012; Aprobado: noviembre 2013.

Abstract:

Although the use of a paternalistic style of management is widespread in the non-Western context, it has only recently received attention from Western scholars. in this study, we compare the presence of a paternalistic style of management and delegation practices across two culturally different organizational contexts, namely Chile and the Us. We also examine the effects of these management practices on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in both contexts. Results suggest that delegation of authority was more common in the Us than in Chile, whereas paternalism was higher in Chile than in the Us. Furthermore, delegation and paternalism were positively related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment in both countries. Unexpectedly, delegation had a stronger effect on job satisfaction and organizational commitment than a paternalistic style of management in the Chilean context, whereas the opposite was found in the Us sample. moreover, the effect of a paternalistic management style on both job satisfaction and organizational commitment seemed to be fully mediated by delegation in Chile. We discuss both the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

keywords: Paternalism, delegation, management, Job satisfaction, Job Commitment.

Resumen:

Si bien el estilo gerencia! paternalista está generalizado en el contexto no occidental, fue solo recientemente que recibió atención por parte de académicos occidentales. En este estudio, comparamos la presencia de un estilo gerencial paternalista y de las prácticas de delegación en dos contextos organizacionales culturalmente diferentes, a saber, Chile y los estados Unidos. También examinamos los efectos de estas prácticas gerenciales sobre la satisfacción laboral y el compromiso organizacional en ambos contextos. Los resultados sugieren que la delegación de autoridad es más común en estados Unidos que en Chile, mientras que el paternalismo es mayor en Chile que estados Unidos. Además, la delegación y el paternalismo están relacionados positivamente con la satisfacción laboral y el compromiso organizacional en ambos países. Inesperadamente, la delegación tiene un mayor efecto sobre la satisfacción laboral y el compromiso organizacional que un estilo gerencial paternalista en el contexto chileno, mientras que lo contrario ocurre en la muestra de estados Unidos. Adicionalmente, el efecto de un estilo gerencial paternalista, tanto sobre la satisfacción laboral como sobre el compromiso organizacional, parece estar completamente mediado por la delegación en el caso chileno. Discutimos las implicaciones teóricas y prácticas de estos hallazgos.

Palabras Clave: paternalismo, delegación, gestión, satisfacción laboral, compromiso laboral.

Résumé:

Bien que le type de gérance paternaliste soit généralisé dans le contexte non occidental, elle n'a retenu que récemment l'attention des spécialistes occidentaux. Dans cette étude, nous comparons la présence d'un style de gérance paternaliste et les pratiques de délégation dans deux contextes d'organisation culturellement différents, à savoir le Chili et les États-Unis. Nous examinons également les effets de ces pratiques de gérance sur la satisfaction professionnelle et l'engagement organisationnel dans ces deux contextes. Les résultats suggèrent que la délégation d'autorité est plus fréquente aux États-Unis qu'au Chili tandis que le paternalisme est plus important au Chili qu'aux États-Unis. En outre, la délégation et le paternalisme sont liés positivement à la satisfaction professionnelle et à l'engagement organisationnel dans les deux pays. D'une manière inattendue, dans le contexte chilien, la délégation a plus d'effet sur la satisfaction professionnelle et l'engagement organisationnel qu'un style de gérance paternaliste alors que c'est le contraire dans notre échantillon des États-Unis. En outre, l'effet d'un style de gérance paternaliste, tant sur la satisfaction professionnelle que sur l'engagement organisationnel, semble être totalement modéré par la délégation dans le cas chilien. Nous discutons des implications théoriques et pratiques de ces constatations.

Mots-Clés: paternalisme, la délégation, la gestion, la satisfaction professionnelle, l'engagement de l'emploi.

Resumo:

Embora o estilo gerencial paternalista esteja generalizado no contexto não ocidental, foi só recentemente que recebeu atenção por parte de académicos ocidentais. Neste estudo, comparamos a presença de um estilo gerencial paternalista e das práticas de delegação em dois contextos organizacionais culturalmente diferentes, que são o Chile e os estados Unidos. Também examinamos os efeitos destas práticas gerenciais sobre a satisfação trabalhista e o compromisso organizacional em ambos os contextos. Os resultados sugerem que a delegação de autoridade é mais comum nos estados Unidos do que no Chile, enquanto o paternalismo é maior no Chile do que nos estados Unidos. Além disso, a delegação e o paternalismo estão relacionados positivamente com a satisfação trabalhista e o compromisso organizacional em ambos os países. Inesperadamente, a delegação tem maior efeito sobre a satisfação trabalhista e o compromisso organizacional do que um estilo gerencial paternalista no contexto chileno, enquanto na amostra dos estados Unidos acontece o contrário. Adicionalmente, o efeito de um estilo gerencial paternalista, tanto sobre a satisfação trabalhista como sobre o compromisso organizacional, parece estar completamente intermediado pela delegação no caso chileno. Discutimos as implicações teóricas e práticas destes achados.

Palavras-Chave: paternalismo, delegação, gestão, satisfação no trabalho, comprometimento com o trabalho.

Introduction

Although there is a body of literature within different disciplines and perspectives that deals with paternalism, few empirical studies have been published about paternalism from a comparative perspective. there is also a lack of consensus as to whether or not having a paternalistic style of management (PSM) is an effective approach (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006), and there are contending views regarding whether it is a positive or negative approach, according to contextual and cultural factors (Martinez, 2005). Certainly, there is ongoing controversy about the impact of PSM on organizations and management and much of this debate is based on judgments with little empirical basis.

Given that business today is, almost by default, international and companies deal with workforces from multiple countries and cultures on a daily basis, companies and executives need to learn about the best ways to approach and manage foreign workforces (Gelfand, Erez & Aycan, 2007). in this line, a better understanding of how and where PSM is effective might enlighten managers and organizations on how to behave appropriately offshore.

This study examines two aspects: a) the relationship between PSM and delegation, and b) job satisfaction and organizational commitment in Chile and the Us. Our purpose is to establish whether samples coming from these two countries differ significantly in how they consider that paternalism and delegation are exercised in their workplaces, and if these practices contribute to a greater overall job satisfaction and organizational commitment in staff from these two countries.

PSM is the consequence of a complex mix of fatherly benevolence, stringent discipline and moral leadership behavior (Cheng, Chou, & Farh, 2000). Lee (2001, p. 858) characterized PSM as a "warm and genuine human bond", involving a careful balance between authority and benevolence. PSM, thus, is based on a hierarchical relationship in which an authority figure guides both the professional and personal lives of employees in a way resembling that of a parent. The employees, in turn, reciprocate this support and guidance with loyalty and deference (Gelfand, Erez & Aycan, 2007).

PSM entails a closer personal bond between managers and employees, as managers are expected to be concerned not only with the employees' professional lives, but also with their personal lives, going beyond the boundaries of the workplace (Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang, & Farh, 2004). Under PSM, managers are expected to be present at non-work related activities that are important for employees such as weddings and funerals (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006). PSM, thus, involves a social exchange, where what managers offer employees goes beyond short-term monetary rewards, including extended consideration of employees' wellbeing and careers within the organization. Employees, in exchange for this care, put in extra effort at work, including long-term sacrifices, and undertaking tasks beyond their duties, feeling personally engaged with the goals of the organization (Tsui, Pearce, Porter, & Tripoli, 1997). Nevertheless, much of the discussion about PSM has been characterized by controversy, and several authors consider PSM a poor way to lead employees. some have described paternalism as a "benevolent dictatorship" or as a subtle form of discrimination (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2008). It is a well-known fact that PSM is partially based on the idea that a manager has a large amount of discretion over employees' activities and behavior, and while some researchers consider this disparity normal or even constructive, others see it as outdated and undesirable. For instance, Rodriguez and Rios (2007) believe that a central feature of PSM is the low or absent delegation of authority due to the limited trust in the decision-making capacity and performance of employees. Such a lack of delegation can cause paternalistic managers to experience strain and exhaustion as it discourages competent employees. PSM also prevents employees from taking initiatives, and risks leaving them in a comfortable position in which they avoid being held accountable for errors and outcomes (Rodriguez & Rios, 2007).

Internationally speaking, it has been suggested that PSM is one of the most prominent features of the Pacific Asian managerial systems (Dorfman & Howell, 1988). Indeed PSM, has been empirically studied in Korea (Pu, Huang, & Kuo, 1990), China (Cheng et al., 2004, Cheng, Chou, & Farh; 2000), Taiwan (Chao & Kao, 2005; Hsieh, 2004), Indonesia (Irawanto, 2008), Vietman (Hoang, 2008) and India (Sinha, 1990). In general, PSM tends to be valued rather differently across countries and it has been suggested that the positive or negative outcomes within a country depend on its prevalent contextual and cultural values that would moderate the relationship between the management style and its consequences (Gelfand et al., 2007).

An example of an Asian country in which PSM has been recognized as successful in the workplace is Korea. Lee (2001) has suggested that businesses in Korea have greatly benefited when moving towards a PSM. This approach has been found to increase productivity and reduce job-related accidents, separation rates and job attrition in Korean organizations. PSM appears to be rooted in the Confucian heritage, extended family system, and rice-agricultural production system (Lee, 2001). Other studies have shown that firms from China, Pakistan, India, Turkey and Mexico show higher paternalistic practices than firms in countries such as Canada, Germany and Israel (Aycan et al., 2000). Employees in China and Taiwan have also been found to highly value PSM (Cheng et al., 2004; Liang, Ling & Hsieh, 2007). Yetim and Yetim (2006) found that PSM, power distance and collectivism was significantly associated to employees' job satisfaction. According to Aycan (2001), PSM has been found to be a socio-cultural characteristic of Asian, Middle-eastern, and Latin American cultures, where PSM is commonplace and widespread and it is considered to humanize workplaces.

In sum, the use, meanings and consequences of PSM seem to differ across countries and cultural contexts. In some countries, PSM may be seen as a violation of privacy and deemed as a disqualifying mechanism to the advantage of managers, whereas in others, it might be considered as the only viable option to lead employees. In their study, Aycan and colleagues (2000) found that in seven out of ten countries that they studied, PSM had a positive effect on obligations towards others, but also a negative effect on employee pro-activity. Only half of the countries showed a positive relationship between paternalism and employee participation.

Prior studies in the Latin-American context also described PSM as a prevalent approach in the region. Harbison and Myers (1959) found, early on, that in some countries (e.g. Chile), managers tended to take a paternalistic role towards employees leaving very little room for them to make decisions. In other countries, in contrast, this approach towards employees was not present at all or even deemed as counterproductive. In their 23-country study, these authors concluded that the cultural and institutional particularities of countries explained and sustained these diverse managerial approaches. PSM has been recognized as a distinctive facet of the managerial culture in regions where social and working patterns are rooted in a context of large farms ("haciendas") and landlords ("terratenientes") from colonial times, where these patterns still exist Elvira & Davila, 2005; Martinez, 2005; Romero, 2004).

Further, Mexican workers have been found to score high on paternalistic values (Martinez, 2003; 2005), something that has been understood as an expression of the country's cultural orientation, with much respect for hierarchical relationships and strong family values. In a more recent study, Rodríguez and Ríos (2007) compared the managerial approaches of two prominent Chilean banks and found that both banks had a PSM, without this having a negative effect on the banks' productivity. This study came to the conclusion that paternalism did not in any way hinder the productivity of the organizations and suggested that this kind of approach might be perfectly compatible with certain developed countries and those on their way to becoming one (Rodríguez & Ríos, 2007). Beside, in an exploratory study, Romero (2004) established that the "patron" management style is the most common way of managing people in Latin America, and many other studies have found paternalism to be a relevant part of labor relations in different Latin American countries (Gomez, 2001; Tanure, 2005). Although these studies are in no way representative of the countries studied, and there is a general shortage of empirical studies in this field in Latin America, they do suggest that PSM might have a positive impact on job satisfaction in the Latin-American context (Osland, Franco & Osland, 1999). Although the majority of the management studies that have historically been carried out have been performed in the United states by North American researchers (Clark, Gospel & Montgomery, 1999; Dickson, DenHartog & Mitchelson, 2003; Elahee & Vaidya, 2001), only a few have looked at PSM there (Pellegrini, Scandura & Jayaraman, 2010).

When it comes to delegation of authority, several studies have compared delegation in the Us with the delegation of authority in other countries, generally concluding that this is a management practice that is significantly more common in the Us than in many other countries, such as Japan, Mexico, Spain, and Italy (Lincoln, Hanada & Mc-Bride, 1986; Pavett & Morris, 1995; Van de Vliert & smith, 2004). Few empirical studies have looked at delegation in the Chilean work context, but in their analysis of the literature and interview data, Abarca, Majluf and Rodriguez (1998) found a low participation that was limited to information sharing on topics such as norms, benefits, safety, objectives, and values. However, Abarca and colleagues (1998) found that educated people and individuals at higher positions in the organization showed greater autonomy, without being afraid to take risks, and were happy to assume the responsibilities that come with decision making. These findings are in accordance with those by Bassa, who, in a dissertation written in 1996, found that the willingness to participate in decision-making and initiatives within Chilean organizations was clearly related to educational and hierarchical level. In this study, 80% of workers who had gone to elementary school and 52% of workers with a high-school education expected their superiors to always make the decisions about difficult situations. In contrast, only 8% of workers with a graduate degree and 15% of those with undergraduate studies, agreed with these statements.

Job satisfaction and organizational commitment are two concepts that have been widely studied internationally. Job satisfaction is one of the most amply studied organizational variables. It is often referred to as employees' global response to their job both in terms of attitudes and affections. Makanjee, Hartzer and Uys (2006) defined job satisfaction as the way in which individuals think and feel about their work experience. Loui (1995) studied the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment among 109 workers at a juvenile detention center and found a positive relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. There are many aspects of employee commitment: commitment to the manager, occupation, profession, career and organization (Meyer & Allen, 1997). According to this view, organizational commitment focuses on employees' commitment to the organization. Moreover, Meyer and Allen (1997) have reported that organizational commitment is related to organizational performance.

A great number of comparative studies have examined management practices or expectations towards management styles, according to cultural values. One of the most commonly used systems to describe cultural values across countries is that of Hofstede (1980). In countries with higher power distance, employees accept that authority is unequally distributed in society, and they tend to be more compliant and would expect a PSM (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Some studies have shown a positive effect of PSM in higher power distance cultures (Aycan et al., 2000), whereas the same approach is perceived negatively in low power-distance countries due to its intrinsic authority and parental role taking. Another dimension that has been related to PSM is collectivism. In collectivistic cultures, people tend to identify themselves with the groups that they are affiliated to, rather than with their personal individual achievements. In contrast, people in individualistic societies value autonomy, self-determination and independence (Perez Arrau, Eades & Wilson, 2012). Given that Chilean employees come from a collectivistic and high power distance culture, it is not unreasonable to expect that Chilean managers will exhibit higher levels of PSM and lower levels of delegation practices. It is also expected that PSM will lead to higher levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in a collectivistic and higher power distance country such as Chile. At the same time, we expect that delegation would be related to higher levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the US, given that it has been described as having an individualistic and low power distance value orientation. According to these arguments, we pose the following four hypotheses for our study:

Hypothesis 1: A significantly more paternalistic management style will be reported for Chile as compared to the US.

Hypothesis 2: significantly more delegation will be reported in the Us than in Chile.

Hypothesis 3: PSM will be associated with a higher level of job satisfaction in Chile, whereas delegation will be associated with a higher level of job satisfaction in the US.

Hypothesis 4: PSM will be associated with a higher level of organizational commitment in Chile, whereas delegation will be associated with a higher level of organizational commitment in the US.

Methodology

Sample

Data was collected from 469 managerial and non-managerial employees from Chile and the US. The samples in both countries were collected by Faculty members and master's students, and organizations were chosen according to their accessibility and willingness to take part in the study. The respondents came from a variety of business sectors, such as Manufacturing, Marketing, Finance, Government and education.

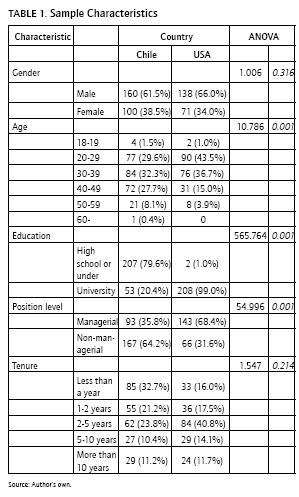

As can be seen in Table 1, the background of the respondents was relatively varied, with 66% of the Us sample being male and 34% female. The distribution for the Chilean sample was 61.5% males and 38.5% females. The respondents came from a variety of educational backgrounds, with a majority (80%) of the Chilean sample having completed a technical trade at the most, whereas 99% of the Us sample had at least a Bachelor's degree. For the case of the Chilean sample, 64% of the participants were supervised, whereas 68% of the Us participants had supervisory functions. Regarding the age of the respondents, the mean age of the US sample was 32.6 years, whereas for the Chilean sample it was 35.4 years. The demographic data of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Instrument

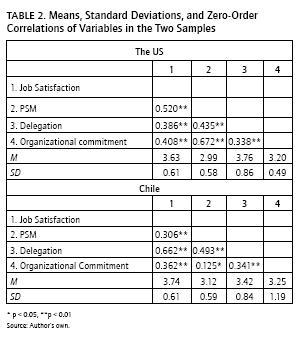

A questionnaire with a total of 51 items was assembled based on four scales measuring paternalism (Aycan, 2006), job satisfaction (Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, 1967), delegation (Yukl, Wall, & Lepsinger, 1990) and organizational commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990). These scales consisted of 15, 21, 7 and 8 items, respectively. Each item was presented as a statement to be rated according to the respondent's relative agreement or disagreement, on a 5-point scale. The four scales have been previously used and tested and have been found to have adequate psychometric properties (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2008). In the case of the Chilean sample, the scales were translated into Spanish, checked by two bilingual researchers, and later back-translated by a third researcher, to ensure the instrument's comparability across languages. In order to assess the reliability of the scales, an internal consistency analysis was carried out with Cronbach's alpha (Cronbach, 1951). The internal consistency coefficients were good for all four scales in both samples (a>0.6). The mean scores of both countries on the four scales are presented in Table 2.

Results

In order to test the two hypotheses, that PSM would be significantly higher in Chile than in the Us and that the opposite would be found for delegation (i.e. significantly higher in the Us than in Chile), two one-way ANOVAs were carried out, with country and managerial level as independent variables, and PSM and delegation as dependent variables. According to these analyses, PSM was found to be significantly higher in Chile than in the Us, F(1,465) = 6.22, p<0.05, confirming the first hypothesis. The second hypothesis was also confirmed as delegation was found to be significantly higher in the Us than in Chile, F(1,465) = 7.05, p<0.01. Apart from a main effect per country, a significant difference was also found between managers and non-managers, with managers reporting significantly more delegation than non-managers across the two samples, F(1,465) = 18.73, p<0.001.

Hypotheses 3 and 4, concerning the effects of PSM and delegation on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in Chile and the Us, were tested through multiple regression analyses for both countries. A look at the bi-variate correlations in Table 2, reveals significant positive correlations between both PSM and delegation and job satisfaction in the Chilean sample (r=0.31, p<0.01; r=0.66, p<0.01) and the Us sample (r=0.52, p<0.01; r=0.39, p<0.01). significant positive correlations were also found between both PSM and delegation, and organizational commitment in Chile (r = 0.13, p<0.05; r=0.34, p<0.01) and the Us (r=0.67, p<0.001; r=0.34, p<0.01).

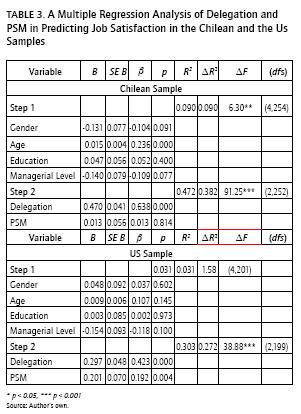

In order to test hypothesis 3, gender, age, education and managerial level of the participants were entered as control variables at step 1 of the analysis, whereas PSM and delegation were entered at step 2, to examine the effect of these two practices on job satisfaction in both countries. In the regression analysis of the Chilean sample, the demographic variables were found to significantly predict job satisfaction, F(4, 254) = 6.30, p < 0.001, explaining 9.0% of the variance. However, the only demographic variable to contribute significant variance was age of the participants. In step 2, the two management practices contributed a further 38.2%, delta F(2, 252) = 91.25, p < 0.001, although the only managerial practice to contribute significant, unique variance was delegation. For the Us sample, the demographic variables in step 1 did not predict job satisfaction, F(4, 201) = 1.58, p = 0.18, (see Table 4). In step 2, PSM and delegation accounted for 30.3% of the variance in job satisfaction, delta F(2, 199) = 38.88, p< 0.001, with both predictor variables statistically predicting job satisfaction.

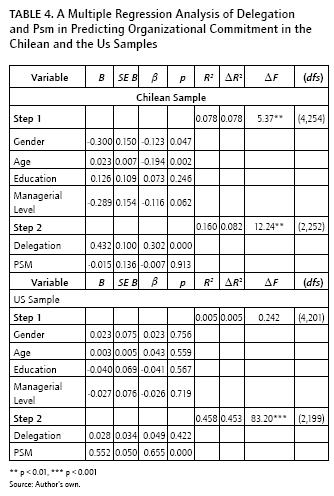

Hypothesis 4, stating that organizational commitment would be related to PSM in Chile, and delegation in the Us was also tested using multiple regression analyses. Gender, age, education and managerial level of the participants were again entered as control variables at step 1 of the analysis, whereas PSM and delegation were entered at step 2, to examine the effect of these two practices on organizational commitment in both countries.

In the regression analysis of the Chilean sample, the demographic variables were found to significantly predict organizational commitment, F(2, 255) = 5.93, p = 0.001, explaining 6.5% of the variance. The two demographic variables that significantly explained the variance were participant age and gender. In step 2, the two management practices contributed a further 9%, AF(2, 253) = 13.45, p < 0.001, although when entered together into the analysis, only delegation contributed significant, unique variance. For the Us sample, the demographic variables in step 1 did not predict organizational commitment, ΔF(4, 201) = 0.24, p = 0.91, (see Table 4). In step 2, PSM and delegation accounted for 45.3% of the variance in organizational commitment, ΔF(2, 199) = 83.20, p < 0.001, with only PSM contributing significant, unique variance.

As these findings might indicate the presence of mediator variables, we carried out mediation analyses based on the recommendations by Baron and Kenny (1986). To meet the criteria for mediation, a predictor must be associated with the mediator, the mediator must predict the outcome, and the effect of the predictor on the outcome must be reduced when the mediator is included in the analysis. There is full mediation if a predictor has no effect once the mediator is included in the equation and partial mediation occurs if there is a significant reduction in the effect of the predictor when the mediator is included. For the Chilean sample we explored the existence of a mediating effect of delegation on the relationship between paternalism and job satisfaction, and on the relationship between paternalism and organizational commitment, as previously found significant correlations disappeared when delegation was entered into the equations. When we carried out the three steps recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986), we found that (1) delegation significantly predicted paternalism &β = 0.350, p<0.001); that (2) paternalism significantly predicted job satisfaction (β = 0.306, p<0.001) and organizational commitment (β = 0.125, p<0.001); and finally that (3) when regressing job satisfaction and organizational commitment on paternalism and delegation simultaneously, the correlation between paternalism and job satisfaction and between paternalism and organizational commitment disappeared (see Table 3 and 4, respectively). According to Baron and Kenny (1986), this would indicate a perfect mediation. Moreover, for the US sample, we explored whether there was a mediating effect of paternalism on the relationship between delegation and organizational commitment, as the delegation variable also failed to reach significance when entered into the equation together with paternalism. We confirmed this mediation, as the following steps were significant: (1) delegation significantly predicted paternalism (β = 0.435, p<0.001); (2) delegation significantly predicted organizational commitment (β = 0.192, p<0.001); and (3) when delegation and paternalism were entered into the equation together, the relationship between delegation and organizational commitment decreased [see Table 4).

Discussion

The purpose of our study was to examine the level of PSM and delegation perceived by staff working across different organizations in Chile and the Us and to measure the effect of paternalism and delegation of authority on job satisfaction and organizational commitment across two samples coming from these two countries. PSM is a particularly interesting area of study, as it is a managerial approach that has been found to be widespread in different regions of the world, even though it is still surrounded by controversies regarding its effectiveness. In this line, we compared the levels of PSM and delegation practices between two samples from culturally different countries, and we also looked at the relationship between these two management styles and job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

The first hypothesis in this study stating that PSM would be significantly higher in Chile than in Us was supported. This means that managers in the Chilean exhibited more paternalistic behaviors when dealing with employees than their counterparts in the Us. Managers from Chile were considered to show more interest in their employees' personal lives than their counterparts in the US. They were also more prone to create a family environment in the workplace and to give advice to employees on different matters.

The second hypothesis of this study posed that delegation practices would be significantly higher in the Us than in Chile, and this was also supported, indicating that managers from the Us encouraged employees to define, by themselves, the best ways to carry out assignments and to take the initiative to solve job related problems to a larger degree than their Chilean counterparts. Us managers also transferred authority to employees in significant decisions and allowed them to execute these without managerial support to a larger extent than the Chilean managers.

Hypotheses 3 and 4 were formulated to examine the relationship between PSM and delegation on the one hand, and job satisfaction and organizational commitment on the other. extant international studies suggest that PSM has a positive impact on job satisfaction in more collectivistic and high power distance cultures (Aycan et al., 2000; Aycan, 2006; Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006), which is why we expected that this management style would increase job satisfaction and commitment in Chile. However, less was known about the effect of this management style in the US context, and the effect of delegation has been much more amply studied in the US than in Chile (Lincoln, Hanada & McBride, 1986; Pavett & Morris, 1995; Van de Vliert & Smith, 2004).

Interestingly, although significant correlations were found between both delegation and job satisfaction, and PSM and job satisfaction, respectively, PSM failed to reach significance in the Chilean sample when entered together with delegation practices into the hierarchical regression analysis to explain job satisfaction. Only a small partial correlation over and above that of delegation was found between PSM and job satisfaction, suggesting that this correlation might be mediated by delegation. However, when looking at the US sample, both PSM and delegation were found to be positively related with job satisfaction. This suggests that both PSM and delegation have a significant effect on the satisfaction of the respondents in the US sample.

The fourth hypothesis looked at the effect of PSM and delegation on the organizational commitment in Chile and the US. One could expect that PSM would influence the way in which employees become emotionally attached to the organization and personally engaged in their work. However, although PSM was found to be significantly related with organizational commitment in Chile, this correlation was not very high, with PSM only explaining 1.6% of the variance of organizational commitment. Moreover, when entered together with delegation into the equation, only delegation obtained significance. For the Us, the opposite was found, with only PSM reaching significance when entered together with delegation into the equation to explain organizational commitment. These findings lead us to carry out mediation analyses which were confirmed for both job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the case of Chile, indicating that the correlation between PSM and job satisfaction and between PSM and organizational commitment would actually be explained by the effect of delegation on these two variables. In contrast, mediation was found between delegation and organizational commitment in the US sample, with this correlation actually being partially mediated by the effect between PSM and organizational commitment.

An important strength of the current study, which is part of the early findings of an international joint project investigating PSM across countries, is that it looks at PSM from a cross-cultural perspective, comparing two Western cultures that differ across two cultural dimensions: individualism-collectivism and high-versus low-power distance. Collectivistic and high power-distance values have been found to be congruent with paternalism in earlier studies (Aycan, 2006).

There are a couple of weaknesses of the current study that relate to the two samples. The first weakness is related to the comparability of the two samples. A significant proportion of the participants in the Us sample had at least a Bachelor's degree, whereas only 20% of the Chilean sample had a University degree and a larger proportion of employees had supervisory functions in the Us sample. There was also a significant age difference between both groups, with the Chilean sample having older participants than the Us sample. This might have generated a generational effect on the perception of PSM and delegation. Different generations might regard delegation and/or PSM differently. Despite these demographic differences found between the two samples, when performing the two-way analysis of variance, a main effect for managerial level was found for delegation but not for PSM, indicating that the managers across both countries reported more delegation than non-managers, whereas no difference was found regarding PSM. In contrast, when education level and managerial level were entered together with the other demographic variables into the regression analyses, no significant effect of these two variables was found in either of the analyses. In any case, in a future study, it would be interesting to investigate whether PSM and delegation are related to age or the educational level of professionals. Also important to note is that 26.3% of the Us sample were of Latin American background, which might explain the positive correlations found between paternalism and job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the Us sample, something that has not been found in earlier studies carried out with participants from this country (Pellegrini, Scandura, & Jayaraman, 2010).

In brief, the results of this study showed that Chilean managers are perceived as more paternalistic and less prone to delegate authority than their US counterparts. At the same time, the job satisfaction and organizational commitment in Chilean employees were more positively related to delegation than paternalism, whereas the opposite was found in US employees. In the Us sample, both delegation and paternalism were associated with job satisfaction, whereas only paternalism was associated with organizational commitment when examined together with delegation. A feasible explanation of this finding could reside in the fact that in the Chilean context, delegation practices are not as widespread as in the industrialized Western world. Delegation is scarce and by no means taken for granted by employees. Hence when present, it is valued and appreciated as an extra expression of trust and recognition. Simultaneously, for Us employees, delegation of authority is taken for granted within the working relationship adding little to their current levels of satisfaction and/or commitment in their positions. Could it be that management practices that are culturally unexpected, but positively evaluated, have a stronger effect on employees' job satisfaction and/ or organizational commitment?

A second alternative explanation for this finding could be a cultural one. Chilean respondents might not have been as collectivistic as predicted by cultural value orientation models (Hofstede, 2001). The dataset on which Hofstede based his value orientation was collected in 1968 and 1972. In more recent studies, Chilean workers have been described as individualistic (Abarca, Majluf & Rodríguez, 1998; Martinez, 2005; Perez Arrau et al., 2012). Because of this, the two samples might be more similar than originally expected at the outset of this project. Therefore, as this project continues, it would be necessary to assess the value orientations of participants at an individual level. This issue should be further explored, as it is also of interest to explore whether this finding is related to a culture or positional effect. It would be necessary to distinguish whether participants are exposed to PSM and/or delegation or if they are actually the ones exercising these behaviors (e.g. managers themselves).

Finally, in a future study, it would be interesting to explore whether, apart from cultural values, there are other factors, such as institutional ones, that might contribute to explaining the effects of PSM and delegation on job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

References

Abarca, N., Majluf, N., & Rodríguez, D. (1998). Identifying Management in Chile, International Studies of Management and Organization, 28(2), 18-37. [ Links ]

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 63, 18-38. [ Links ]

Aycan, Z. (2001). Human Resource Management in Turkey-Current Issues and Future Challenges. International Journal of Manpower, 22(3), 252-258. [ Links ]

Aycan, Z. (2006). Paternalism: Towards Conceptual Refinement and Operationalization. In U. Kim, K. S. Yang, & K. K. Hwang (eds.), Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context (pp. 445-466). New York: Springer Science. [ Links ]

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., Mendoca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., & Stahl, G. (2000). Impact of Culture on Human Resource Management Practices: A 10-Country Comparison. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49, 192-221. [ Links ]

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. [ Links ]

Bassa, I. A. (1996). Bases culturales para la formulacion de un modelo de gestion estrategica. Dissertation. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago. [ Links ]

Chao, A. A., & Kao, S. R.(2005), Paternalistic Leadership and subordinated stress in Taiwanese enterprises, Research in Applied Psychology, 27, 111-131. [ Links ]

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., & Farh, J. L. (2000). A Triad Model of Paternalistic Leadership: Constructs and measurement. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 14, 3-64. [ Links ]

Cheng, B., Chou, L., Wu, T., Huang, M., & Farh J. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 7, 89-117. [ Links ]

Clark, T., Gospel, H., & Montgomery, J. (1999). Running on the spot? A review of twenty years of research on the management of human resources in comparative and international perspective. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 10(3), 520-544. [ Links ]

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. [ Links ]

Dickson, M. W., Den Hartog, D. N., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2003). Research on leadership in a cross-cultural context: Making progress, and raising new questions. Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 729-769. [ Links ]

Dorfman, P.W. & Howell, J.P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture & effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. In E.G. McGoun (ed.), Advances in international comparative management, 3, 127-149, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Elahee, M. N., & Vaidya, S. P. (2001). Coverage of Latin American business and management issues in cross-cultural research: An analysis of JIBS and MIR 1987-1997. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, 4(12), 21-32. [ Links ]

Gelfand, M.J., Erez, M., & Aycan, Z. (2007). Cross-Cultural Organizational Behavior. Annual Review of Psycology, 58, 479-514. [ Links ]

Gomez, C. F. (2001). Chilean culture: entrepreneurs and workers, The Asian Journal of Latin American Studies, 14(2), 113-160. [ Links ]

Harbison, F., & Myers, C.A. (1959). Management in the Industrial world: An international analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G.H. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, Ca.: Springer. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Hsieh, K. C. (2004). Development and argument of the measurement scale for paternalistic leadership style. Taiwan: National science Council. (NsC93-2413-H-134-007). [ Links ]

Irawanto, D. (2008). The applicability of paternalistic leadership in Indonesia. Journal of Human Capital, 1(1), 67-80. [ Links ]

Lee, H.-S. (2001). Paternalistic human resource practices: Their emergence and characteristics. Journal of Economic Issues, 35(4), 841-869. [ Links ]

Liang, S., Ling, H., & Hsieh, S. (2007). The mediating effects of Leader-member exchange quality to influence the relationships between paternalistic leadership and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Business, 10(2), 127-137. [ Links ]

Lincoln, J., Hanada, M., & McBride, K, (1986). Organizational structures in Japanese and Us manufacturing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31, 338-364. [ Links ]

Loui, K. (1995). Understanding employee commitment in the public organization: A study of the juvenile detention center. International Journal of Public Administration, 18(8), 1269-1295. [ Links ]

Makanjee, R.C., Hartzer, Y., & Uys, I. (2006). The effect of perceived organizational support on organizational commitment of diagnostic imaging radiographers. Radiography, 12(2), 118-126. [ Links ]

Martinez, P.G. (2003). Paternalism as a positive form of leader-subordinate exchange: evidence from Mexico. Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, L, 227-242. [ Links ]

Martinez, P. G. (2005). Paternalism as a positive form of leadership in the Latin American context: Leader benevolence, decision-making control and human resource management practices. In M. Elvira & A. Davila (Eds.), Managing Human Resources in Latin America: An Agenda for International Leaders (pp. 75-93). Oxford, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Meyer, J., P., & Allen, N. J., (1997). Commitment in the Workplace: Theory Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing. [ Links ]

Osland, J. S., Franco, S., & Osland, A. (1999). Organizational implications of Latin American culture: Lessons for the expatriate manager. Journal of Management Inquiry, 8, 219-234. [ Links ]

Pavett, C. & Morris, T. (1995). Management styles within a multinational corporation: A five-country comparative study. Human Relations, 48, 1171-1191. [ Links ]

Pellegrini, E. K., & Scandura, T. A. (2006). Leader-member exchange (LM/), paternalism and delegation in the Turkish business culture: An empirical investigation. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(2), 264-279. [ Links ]

Pellegrini, E. K., & Scandura, T. A. (2008). Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 34, 566-592. [ Links ]

Pellegrini, E. K., Scandura, T. A., & Jayaraman, V. (2010). Cross-cultural generalizability of paternalistic leadership: An expansion of leader-member exchange theory (LMX). Group and Organization Management, 35(4), 391-420. [ Links ]

Perez Arrau, G., Eades, E., & Wilson, J. (2012). Managing human resources in the Latin American context: the case of Chile. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(15), 3133-3150. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M. D., & Ríos, F. R. (2007). Latent premises of labor contracts: paternalism and productivity: Two cases from banking industry in Chile. International Journal of Manpower, 28(5), 354-368. [ Links ]

Romero, E. J. (2004). Latin American Leadership: El Patron and El Lider Moderno. Cross Cultural Management, 11(3), 25-37. [ Links ]

Sinha, J. B. P. (1990). Work culture in Indian context. New Delhi, India: Sage. [ Links ]

Tanure, B. (2005). Human Resource Management in Brazil. In M. Elvira & A. Davila (Eds.), Managing human resources in Latin America: An agenda for international leaders (pp. 111-127). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tsui, A., Pearce, J.L., Porter, L., & Tripoli, A.M. (1997). Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: Does investment in employees pay off? Academy of Management Journal, 40(5), 1089-1121. [ Links ]

Van de Vliert, E., & Smith, P. B. (2004). Leader reliance on subordinates across nations that differ in development and climate. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 381-403. [ Links ]

Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., England, G. W., & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minneapolis: Industrial relations center, University of Minnesota. [ Links ]

Yetim, N., & Yetim, U. (2006). The cultural orientations of entrepreneurs and employees' job satisfaction: The Turkish small and medium sized enterprises (SMES) case. Social Indicators Research, 77, 257-286. [ Links ]

Yukl, G., Wall, S., & Lepsinger, R. (1990). Preliminary report on the validation of the management practices survey. In K. E. Clark and M. B. Clark (Eds.) Measures of Leadership (pp. 223-238). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America. [ Links ]