Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Innovar

Print version ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar vol.24 no.54 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v24n54.46754

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v24n54.46754

Building Chinese Cars in Mexico: The Grupo Salinas-FAW Alliance

Producir autos chinos en México: la alianza entre el Grupo Salinas y FAW

Produire des voitures chinoises au Mexique: l'alliance entre le groupe Salinas et FAW

Produz ir carros chineses no México: A parceria do Grupo Salinas com a FAW

Álvaro Cuervo-CazurraI, Miguel A. MontoyaII

I PhD from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and University of Salamanca. Professor. Northeastern University. Boston, USA. E-mail: a.cuervocazurra@neu.edu

II PhD from University of Barcelona. Professor. Tecnológico de Monterrey, campus Guadalajara. Mexico. E-mail: mmontoya@itesm.mx

Correspondencia: Miguel Angel Montoya Bayardo; ITESM, Campus Guadalajara; Ave. General Ramón Corona 2514. Col. Nuevo México. Zapopan, Jalisco. 45201. México.Tel: (+52) 3336693037.

Citación: Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Montoya, M. A. (2014). Building Chinese Cars in Mexico: The Grupo Salinas-FAW Alliance. Innovar, 24(54), 219-230.

Clasificación JEL: M16, F23, F14.

Recibido: Agosto 2011; Aprobado: Noviembre 2013.

Abstract:

Ricardo Salinas Pliego was the CEO of Grupo Salinas, one of the largest business groups in Mexico, and in 2009 he faced a challenge. Two years earlier, he had negotiated with the Chinese car company FAW to import Chinese cars into Mexico as an initial step towards their manufacturing. However, the global crisis of 2008 made him question the viability of the project and he had to decide whether to close the operation or continue in the hope of a quick recovery. This was a difficult decision because the group had sold several thousand cars and established a network of car dealers. Closing the operation would mean not only losing the investment in the network while having to continue servicing the cars, but would also result in a blow to the reputation of the group. He was pondering what the best option would be.

Key words: alliances, international joint ventures, developing country multinationals, emerging markets, China, Mexico, failure.

Resumen:

Ricardo salinas Pliego era el CEO del Grupo salinas, uno de los mayores grupos empresariales de méxico, y en 2009 enfrentó un desafio. Dos años antes habia negociado con FAW, la empresa automotriz china, para importar autos chinos a México como un paso inicial hacia su manufactura. Sin embargo, la crisis global de 2008 le hizo cuestionar la viabilidad del proyecto y tuvo que decidir si cerrar la operación o continuar con la esperanza de una recuperación rápida. Fue una decisión difícil porque el grupo habia vendido varios miles de carros y habia establecido una red de concesionarios. Cerrar la operación significaria no sólo perder la inversión en la red y al tiempo tener que continuar prestando mantenimiento a los autos, sino además un golpe para la reputación del grupo. Salinas reflexionaba sobre cuál era la mejor opción.

Palabras clave: alianzas, empresas conjuntas internacionales, multinacionales de paises en desarrollo, mercados emergentes, China, México, fracaso.

Résumé:

Ricardo Salina Pliego était le Directeur général du Groupe Salinas, l'une des plus importantes entreprises du Mexique, et en 2009 il s'est trouvé face à un défi. Deux années auparavant, il avait négocié avec FAW, l'entreprise automobile chinoise, pour importer au Mexique des autos chinoises comme un premier pas vers leur montage. Cependant, la crise globale de 2008 l'avait fait s'interroger sur la viabilité du projet et il s'était demandé s'il devait annuler l'opération ou continuer avec l'espoir d'une récupération rapide. Ce fut une décision difficile car le groupe avait vendu plusieurs milliers de voitures et organisé un réseau de concessionnaires. Annuler l'opération ne signifiait pas seulement perdre l'investissement dans le réseau mais devoir continuer à assurer l'entretien des autos, outre un coup porté à la réputation du groupe. Salinas s'interrogeait sur le choix qui serait le meilleur.

Mots-clés: Alliances, entreprises conjointes internationales, multinationales de pays en développement, marchés émergents, Chine, Mexique, échec.

Resumo:

Ricardo Salinas Pliego era o CEO do Grupo Salinas, um dos maiores grupos empresariais do México e, em 2009, enfrentou um desafio. Dois años antes, havia negociado com a FAW, a empresa automotiva chinesa, para importar carros chineses ao México como um passo inicial para a sua fabricação. No entanto, a crise global de 2008 fez com que ele questionasse a viabilidade do projeto e teve que decidir se fechar a operação ou continuar com a esperança de una recuperação rápida. Foi una decisão dificil porque o grupo havia vendido vários milhares de carros e havia estabelecido uma rede de concessionários. Fechar a operação significaria, não só perder o investimento na rede e, ao mesmo tempo, ter de continuar prestando manutenção aos carros, mas também um golpe para a reputação do grupo. Salinas refletia sobre qual era a melhor opção.

Palavras-chave: Parcerias, empresas conjuntas internacionais, multinacionais de paises em desenvolvimento, mercados emergentes, China, México, fracasso.

Grupo Salinas

Grupo Salinas was one of the largest business groups, or conglomerates, in Mexico. By 2009, it had around 45,000 employees working in Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Peru and the United States, and had sales of 63 billion mexican pesos (approximately US$4.6 billion).

Grupo Salinas was composed of four segments:

- Media. Azteca TV was the second-largest producer of Hispanic television content in the world. It operated two national television networks in Mexico, serving 110 million people through more than 300 stations. In 2001, Azteca America was launched to provide TV Azteca's content to U.S. Affiliates.

- Retail and finance. Grupo Elektra was Latin America's leading mass-market specialty retailer, selling electronics, household appliances, furniture, transportation equipment, telephones, and computers, as well as providing financing to facilitate the purchases. It operated 1,900 points of sale in Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Peru, Panama, and Mexico. Azteca Finance Division included all operations that offered financial services to consumers.

- Telecommunications. Iusacell provided wireless telephony in Mexico. It served 3.4 million subscribers, or approximately 7% of the Mexican wireless telecommunications market.

- Social responsibility. Fundación Azteca and Fundación Azteca America were non-profit organizations dedicated to improving health, nutrition, education, and the environment. Fomento Cultural Grupo Salinas promoted the preservation of Mexico's cultural heritage.

History of Grupo Salinas

Grupo Salinas started operations in 1906 in Monterrey, in the state of Nuevo Leon in Northern Mexico, with a furniture factory that Benjamin Salinas Westrup opened with his brother-in-law Joel Rocha. In the 1920s, they established their first store, called Salinas y Rocha, in downtown Monterrey. Unlike other companies at the time, they not only sold furniture but also provided credit to facilitate purchases, which became the formula for success that enabled the company to become one of the largest business groups in Mexico. In 1950, Hugo Salinas Rocha, son of Benjamin Salinas, started manufacturing radios and televisions. In 1952, Hugo Salinas Price, the grandson of the founder and son of Hugo Salinas Rocha, was appointed general manager of the business. In 1959, he opened the first Elektra store. By 1968, Elektra had 12 stores in Monterrey.

The company faced challenges to its business model. In 1976, the devaluation of the peso against the dollar forced the company to temporarily suspend its credit system. In 1987, Hugo Salinas Price retired and named Ricardo Salinas Pliego, his son, as the new CEO of Grupo Elektra. In the middle of a deep economic crisis and facing the possibility of bankruptcy, Ricardo Salinas restructured Elektra. He established a new business model: Low margins, a policy of cash-only payments, and a basic product line. With this, the firm slowly returned to profitability. In 1989 he resumed the provision of credit to consumers. In 1993, Elektra started quoting in the Mexican Stock Exchange.

The group continued to diversify in the 1990s. In 1993, a group of shareholders led by Mr. Salinas Pliego purchased the state-owned Imevisión, which controlled channels 13 and 7, and changed its name to TV Azteca. In 1996, TV Azteca began to produce soap operas, establishing Digital Azteca and Azteca Music. In 1997, TV Azteca began quoting in the Mexican Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange. In 1996, Elektra created Dinero Express, a money transfer system in Mexico. In 1998, Azteca TV made a strategic investment in Unefon, a wireless telephone services company. In 2000, the Salinas Group was established under a new structure and Azteca TV opened its U.S. Subsidiary to focus on the Hispanic market. In 2002, the group obtained a license to create Azteca Bank, which operated in the Elektra stores and provided credit to customers. A year later, it started operating an Afore (management service retirement fund). That same year, the company acquired the majority of Iusacell, which was the third-largest mobile operator in Mexico. In 2005, the company began to franchise its Elektra brand to expand in Latin America. By 2010 it had 795 stores in Mexico, 50 in Peru, 47 in Guatemala, 23 in Honduras, 12 in Panama, 13 in Argentina, and 7 in Brazil.

The Automobile Industry in Mexico

The role of the automotive industry in Mexico's economy was important. It represented 19% of manufacturing GDP and 3.5% of total GDP; exports of auto parts accounted for 12% of total exports; employment generated by the auto industry represented 13% of manufacturing employment; and flows of foreign direct investment in auto parts were 15% of total FDI flows to the manufacturing sector (CIIAM, 2008). Some 650,000 people worked in the automobile industry directly, and 2.5 million people indirectly once distribution, repair, and supply of parts and gasoline were included (Quadratin, 2008). This industry was the main source of foreign exchange within the manufacturing sector.

By 2007, Mexico produced about 2 million light vehicles. Of these, 1.5 million were exported (see Figure 1). Vehicles produced in Mexico included the Chevrolet HHR, GM crossover, Chrysler pickup trucks, VW Beetle and Jetta, Honda Accord, Nissan Versa and Tsuru, Ford Fusion, and Lincoln MKZ (Greene, 2007). Additionally, about 1.2 million vehicles entered Mexico with temporary permits or were legally imported. Many of them were second-hand high-mileage automobiles from the United States, which were marketed informally.

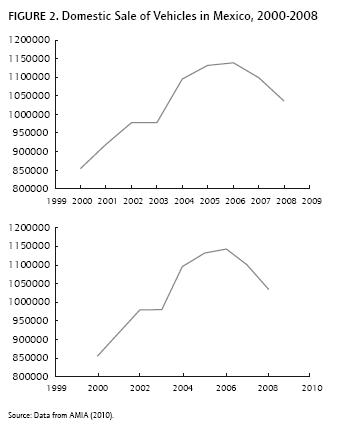

From 2004 to 2007, demand for new cars was over one million units annually (see Figure 2). There was an unmet demand in the middle and lower classes, which represented 63% of the national population. Since three quarters of them did not have a car, there was a potential market of 31 million consumers who needed an inexpensive, reliable, low-consumption, and low-maintenance car (Santana, 2007).

The automobile industry was highly regulated (Prensa de Negocios, 2008). In 1990, the government issued the decree titled Promotion of the Modernization of the Automotive Industry to support exports and improve the international competitiveness of automobile producers. This resulted in a large trade deficit, as the import of materials and components increased. The government tried to reduce the deficit via regulation. According to the Auto Decree 2005, any company wishing to import duty-free vehicles into Mexico would have to make a minimum investment of $100 million in a new plant with an output of 50,000 vehicles per year (Fernández, 2006). Otherwise, an import fee had to be paid for all imported automotive vehicles not manufactured in Mexico (Gobierno de la República, 2003).

Building Chinese Cars in Mexico

Elektra sought to increase the variety of goods in the stores to grow and face competitors. In 2003, it started selling tires and quickly became the third largest dealer in Mexico. The success in selling tires led to the importation of Chinese motorbikes, under the name Italika, which became a very profitable and successful venture. By 2007, italika motorcycles represented 56% of all units sold in mexico. These successes spurred interest in cars. The company had more than 20 years of experience importing products from China to mexico (martínez, 2007).

Grupo salinas wanted to replicate the success of italika and decided to search for a partner with world-class technology that could produce low-priced cars to sell to the low-income market that was not being served by other brands. According to Javier sarro, chairman of the transportation division of Grupo salinas, it took two years of analysis and research (Avilés, 2007).

In 2007, Grupo salinas started a formal search for a Chinese partner to enter the car industry. The major Chinese manufacturers were FAW, Geely, BAW Beijing automobile Works, Beigi Futon Chery automotive, Dongo Feng motor, and Chana. Managers of Grupo salinas had talks with more than 10 Chinese automobile manufacturers, but the talks with Geely were the most promising. Geely was created in 1986 and started producing cars in 1997. It was headquartered in Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang province, and operated six plants with a total production capacity of approximately 300,000 cars per year. Unfortunately, talks with Geely were unsuccessful.

Thus, Group salinas partnered with FAW. Founded in 1953, First automobile Works (FAW) was one of the five major Chinese car manufacturers. The reforms initiated in 1978 saw the growth and transformation of the firm. It incorporated many Japanese production techniques into its manufacturing process to enhance efficiency. In the 1980s, the company moved away from the priorities of a traditional state enterprise to that of a profit-driven organization. In 1991, FAW joined volkswagen in the production of automobiles, and in the period 1991-2001 it formed joint ventures with other foreign firms like toyota, mazda, and Audi. By 2006, it was one the largest vehicle manufacturers in China with 1.4 million cars produced and 140,000 employees. FAW exported cars to 70 countries and, in addition to producing under its own brand; it had joint ventures with toyota, Audi, Hyundai, volkswagen, and mazda (Avilés, 2007; Hoyo, 2007).

Grupo Salinas Motors Business Plan

Grupo salinas and FAW signed a memorandum of understanding in 2007 to start marketing cars in mexico by the first quarter of 2008. They had a long-term project and plans to introduce a new line of automobiles in mexico for low-income consumers, a new market segment that was underserved (Gallegos, 2008).

Initially the vehicles were imported from China, and after three years, they would be produced in mexico. This would enable Grupo salinas to avoid the 50% import duties that Chinese cars would face, which would render them uncom-petitive and unprofitable.

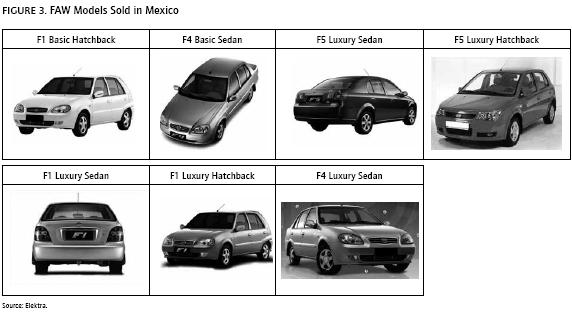

They planned to price imported vehicles below the average of those sold by competitors in mexico. The three models offered by FAW were: the F1 line (1.0-liter engine) in its sedan and hatchback versions; the F4 (1.4-liter engine), which had the same platform and basic versions and equipment; and the F5 in sedan and hatchback (Gallegos, 2008) (see Figure 3). The prices of the cars in mexico were: (1) F1 Basic Hatchback, 69,900 pesos (Us$6,300); (2) F1 Luxury Hatchback, 74,900 pesos (Us$6,850); (3) F1 luxury sedan, 86,900 pesos (Us$7,900); (4) F4 Basic sedan, 89,900 pesos (Us$8,180); (5) F4 luxury sedan, 96,900 pesos (Us$8,815); (6) F5 luxury Hatchback, 104,900 pesos (Us$9,536); (7) F5 luxury sedan, 114,900 pesos (us$10,445).

Cars were sold and financed through a weekly payment system. Azteca Bank provided financing, with a down payment of 10% to 30% and interest rates ranging from 12% to 20%. It had several financing schemes. For example, the F1 hatchback, basic version, was sold with a 30% down payment, 60 months to pay, and payments of 330 pesos per week. Furthermore, it included vehicle maintenance. For an additional 50 pesos more per month, insurance was provided. Seguros Azteca (the insurance company of the Grupo salinas) provided the insurance (Elektra, 2010).

Assembly Plant

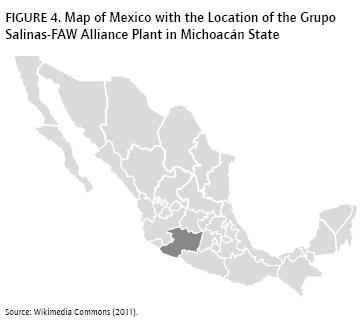

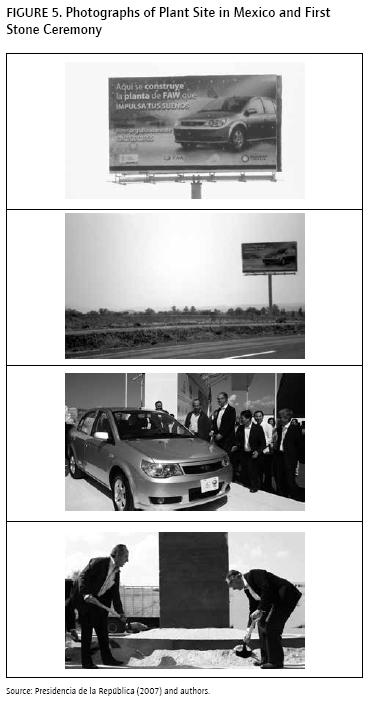

Grupo salinas planned to build a plant in Zinapécuaro in the state of michoacán to manufacture and export compact cars at low prices, using domestic automotive components (see Figure 4 for the location of the plant and Figure 5 for pictures of the site). It would create about 2,000 direct jobs and about 14,000 indirect jobs and was hailed as the largest Chinese investment in mexico. The assembly line was located in the town of Zinapécuaro, with an initial investment of Us$150 million, and with a later investment of Us$100 million to create a distribution and service network (Avilés, 2007). Salinas and FAW Group decided that to be competitive in the segment of inexpensive cars, they needed high production volumes. Therefore, they planned a second phase to increase capacity to 200,000 units per year for the domestic and export markets. The automotive plant had two access paths, one from the mexico-Guadalajara Highway, and the other from the old road to Zinapécuaro, michoacán. The latter was ideal for production and logistics for export markets throughout the Americas from the port of lázaro Cárdenas.

This plant was supposed to begin car production by 2010, so it could meet the rising demand in the country and export to Latin America, beginning with destinations in which Grupo salinas was already present like Brazil, Argentina, Guatemala, Peru, Honduras, and Panama. FAW had a keen interest in exploring the possibility of selling to the Us and Canadian markets from mexico (santana, 2007).

On November 23rd, 2007, the first stone was placed where the FAW automobile assembly plant was supposed to be built, with the presence of the President of the mexican Republic, Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, the director of Grupo salinas, Ricardo salinas Pliego, the President of FAW, CEo Zhu Yanfeng, and the governor of michoacán, lázaro Cárdenas Batel. In the opening ceremony, President Calderón said that the automaker would help social segments with little chance of getting a car acquire one at modest prices. Ricardo salinas Pliego explained that as a first step the vehicles were to come from China and that in three years they would be produced in mexico. once the assembly plant was finished, it would have an annual production capacity of 100,000 cars. Salinas Pliego added: "today is an important day for Grupo salinas. We started a business line that we do not know. We will learn and we will do lots of cars and very well made." salinas Pliego indicated that this was a very important investment for mexico, because a Chinese company saw the country as a very good field for investment. He thanked the General President of FAW Group, Zhu Yanfeng, who took the mexican entrepreneurs into account (Al Volante, 2009).

Additionally, the companies intended to set up R&D laboratories in mexico with an investment of Us$12 million and the objective of designing vehicles and bodies for markets in mexico and Latin America (vera, 2008). on April 7, 2008, as part of the plant project, FAW Group President Wang Gang and the President of Grupo salinas motors, Javier sarro, signed a letter of understanding to create an R&D center.

For michoacán, the plant represented one of its most important investment projects. The government of michoacán projected that it would trigger the industrial development of the state, anchor a new industrial zone, increase the economically active population by more than 5%, create a world-class R&D center, receive China's largest investment in the country, contribute to develop local talent through linkage programs with 12 universities in the state of Mí-choacán, and result in a 5% increase in the GDP of MícIio-acán (Gobierno del Estado de michoacán, 2009).

Importing and selling Chinese Cars

In 2007, Officials from the ministry of Economy authorized the importation of 5,000 F1 and F5 model vehicles from China, which arrived in mexico in october. The cars were disembarked in December, at the port of Lázaro Cárdenas Las truchas, michoacán, on mexico's Pacific coast. However, the cars remained there until they received a release permit and were sold from mid-January of 2008, mainly in the Federal District, the central states of mexico and morelos, the western state of michoacán, and the southeastern state of Guerrero (Estrada & Guzmán, 2007).

The firms built a network of dealers with sales floors and service centers. They did not use franchises so that the process could be completely controlled from the time they assembled the car until it was sold and returned to service, obtaining customer feedback along the way (Hoyo, 2007). The creation of specialized points of sale for the product, brand certified workshops, and access to original spare parts, were part of FAW's strategy (Gobierno del Estado de Michoacán, 2009).

Making decisions in the face of a Crisis

The 2008 Great Contraction that started in the United states and spread globally had a negative impact on the demand for cars in mexico. According to the international organization of Automobile manufacturers (oiCA), world production in 2008 fell by 4.1% over the previous year (AMIA, 2010). The "Asociación mexicana de la industria Automotriz" (mexican Association of the Automotive in-dustry-AmiA) indicated that in the first quarter of 2009, 246,878 vehicles were sold, which was 100,182 fewer than in the same period the previous year. There were various causes for the decline, including the lack of credit, job insecurity, a general rise in prices for cars, as well as the constant increase in gasoline prices, taxes (Vat, isAN, and tenencia, which were annual fees for having a vehicle), and payments for services such as verification, plates, and insurance against theft and accidents. In 2008, automobile credit decreased by 12%. Financial institutions were not only reluctant to provide credit, but also imposed additional restrictions on lending money (CiiAm, 2008a). Fearful consumers stopped buying cars and new vehicle sales in December fell nearly 20%, closing the year with a contraction of 6.8% (Globedia, 2009) (see Figure 1).

Mexico's federal government gave the automobile industry a rescue package to stay afloat during the crisis. "About 60 major companies related to the automotive industry are expected to benefit from technical stoppage Program developed by the mexican government, which is designed to help companies through the third payment of salaries to avoid layoffs" (Cárdenas & Hernández, 2009).

By 2009, FAW found that acceptance of its imported products was low among Mexican consumers, despite the competitive prices, and this compounded the impact of the crisis. The location of the planned plant had been suffering from violence because of the government's war against drug trafficking and organized crime, and subsequent retaliation by drug cartels. Furthermore, FAW received more bad news: their cars did not meet Dot safety and pollution standards in the United states, a market that it wanted to serve from mexico. All these factors led to a delay in the investment in the assembly plant (Frost & sullivan, 2009).

Ricardo salinas Pliego needed to address these challenges. There was lower-than-expected demand for the cars it had already imported and for which it had established a sales and repair network, and the economic crisis and inability to export to the United states threatened the viability of the production plant. As he headed for another meeting, he wondered if there was a future for Grupo salinas in the car industry or whether it would have to stop selling Chinese cars in mexico.

References

Al Volante. (2009, January 07). ¿Quépasó con la nueva planta china de FAW en Michoacán? Retrieved from Al Volante.info: http://www.alvolante.info/nacionales/%C2%BFque-paso-con-la-nueva-planta-china-de-faw-en-michoacan/. [ Links ]

AMIA. (2010, April 15). Estadísticas. Retrieved from Asociación mexicana de la Industria Automotriz: http://www.amia.com.mx/estadisticasvm.html. [ Links ]

Avilés, R. (2007, December 12). Comercializará Elektra autos chinos. Retrieved from Mural.com: http://mural-guadalajara.vlex.com.mx/vid/sarro-comercializara-elektra-chinos-80548140. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, L., & Hernández, U. (2009, February 09). México sufre el rescate automotriz de EU. Retrieved from CNN Expansión: http://www.cnnexpansion.com/negocios/2009/02/06/mexico-sufre-el-rescate-automotriz-de-eu. [ Links ]

CIIAM. (2008a, July). Congreso Internacional de la Industria Automotriz en México. Retrieved from http://www.ciiam.com/graficas/cifras2009.pdf. [ Links ]

CIIAM. (2008b, July). Industria nacional de autopartes. Retrieved from Congreso internacional de la industria Automotriz en México: http://www.ciiam.com/index2.html. [ Links ]

Colaborators of OpenstreetMap. (2013, November 13). OpenSteetMap. Retrieved from openstreetmap.org. [ Links ]

Elektra. (2010, October 06). Grupo Salinasy FAW Group impulsan la industria automotriz mexicana. Retrieved from Elektra FAW: http://www.elektra.com.mx/elektra/UltimasNoticias/Faw.aspx. [ Links ]

Elektra. (n.d.). FAW. Retrieved from Elektra: https://www.elektra.com.mx/Elektra/ArmaConsulta.aspx?menu=true&ICLAS=2709&Ind Gle=Transporte-Faw. [ Links ]

Estrada, A., & Guzmán, E. (2007, January 21). Generará planta automotriz 12 mil empleos: Sedeco. Retrieved from Reporte Digital. Agencia de Noticias de Michoacán: http://www.reportedigitalcom.mx/noticias/negocios/10134.html. [ Links ]

Fernández, A. O. (2006, August). La Industria Automotriz en México y el TLCAN. Un análisis de series de tiempo. Retrieved from Observatorio de la Economía Latinoamericana: http://www.eumed.net/cursecon/ecolat/index.htm. [ Links ]

Frost & Sullivan. (2009, september 22). La industria automotriz mexicana frente a la situación económica actual. Retrieved from Frost & Sullivan: http://www.portalautomotriz.com/content/2/module/news/op/displaystory/story_id/23097/format/html/. [ Links ]

Gallegos, V. A. (2008). Marco referencial capítulo IV. In Innovación disruptiva: análisis del caso Salinas Motors. Cholula: Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Escuela de Negocios y Economía Departamento de Empresas y Mercadotecnia. [ Links ]

Globedia. (2009, May). Cae la venta de automoviles en México. Retrieved from Globedia beta Noticias de México: http://mx.globedia.com/no-existe-noticia/cae-venta-automovil-mexico. [ Links ]

Gobierno de la República. (2003, Decemeber 31). Decreto para el apoyo de la competitividad de la industria automotriz. Retrieved from Diario Oficial de la Federación: http://www.economia.gob.mx/files/transparencia/D25.pdf. [ Links ]

Gobierno del Estado de Michoacán. (2009, march 07). Planta FAW-GS Motors. Retrieved from Agencia Estatal de Atracciones de inversiones y Proyectos Estratégicos: http://www.michoacan.gob.mx/aeaipe/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=281&Itemid=292. [ Links ]

Greene, J. (2007, september 25). México, líder en América Latina en la producción y exportación de vehículos. Retrieved from El siglo de Torreón: http://www.elsiglodetorreon.com.mx/noticia/299738.mexico-lider-en-america-latina-en-la-producci.html. [ Links ]

Hoyo, R. (2007, December 04). Llegaron los autos Chinos FAW de la mano de Grupo Salinas. Retrieved from Autocosmos: http://noticias.autocosmos.com.mx/2007/12/04/llegaron-los-autos-chinos-faw-de-la-mano-de-grupo-salinas. [ Links ]

Martinez, J. M. (2007, November 30). Autos chinos desde 350 pesos semanales. Retrieved from CNN Expansión: www.cnnexpansion.com/negocios/2007/11/29/autos-chinos-desde-350-pesos-semanales. [ Links ]

Prensa de Negocios. (2008, January 23). Ahíla lleva, vende Elektra 800 autos chinos FAW en 3 semanas. Retrieved from El semanario: http://www.elsemanario.com/news. [ Links ]

Presidencia de la República. (2007, November 23). El presidente Calderón en la colocación de la primera piedra de la planta ensambladora de automóviles del Grupo Salinas y Grupo Faw. Retrieved from Presidencia de la República: http://calderon.presidencia.gob.mx/2007/11/el-presidente-calderon-en-la-colocacion-de-la-primera-piedra-de-la-planta-ensambladora-de-automoviles-del-grupo-salinas-y-grupo-faw/. [ Links ]

Quadratín. (2008, April). Quadratín agencis de información y análisis. Retrieved from http://www.quadratin.com.mx/www1/noticia.php?id=34421. [ Links ]

Santana, E. (2007). Prevé Grupo Salinas formar cluster industrial. Retrieved from Énfasis Logística: http://www.logistica.enfasis.com/notas/11416-Prevé-Grupo-Salinas-formar-clúster-industrial. [ Links ]

Vera, P. (2008, November 23). Coloca Calderón primera piedra de FAW Group. Retrieved from Reporte Digital. Agencia de Noticias de Michoacán: http://www.reportedigital.com.mx/noticias/negocios/9213.html. [ Links ]

Wikimedia Commons. (2011, August 04). Michoacan in Mexico (location map scheme). Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michoacan_in_Mexico_(loca-tion_map_scheme).svg. [ Links ]

Teaching notes

Overview

In 2007, Ricardo salinas Pliego, the President of Grupo salinas, one of the largest Mexican business groups, started negotiations with FAW, a leading Chinese car company, to import Chinese cars to Mexico as a first step towards the manufacturing of Chinese automobiles in Mexico to serve the domestic market and export to the United states and Latin America.

The group, which had been selling Chinese-made italika motorcycles through its retailer, Elektra, was hoping to repeat this success by selling Chinese cars, but needed a partner. The search for a partner led to an alliance with the Chinese firm FAW. Planning to produce cars in Mexico enabled the firms to avoid paying the punishing import tariffs of 50%, which would make the imports uncompetitive. At the end of 2007, the company celebrated the first stone ceremony for the assembling plant in Zinapécuaro, Michoacán, with the presence of the President of Mexico, indicating the importance of the alliance for job creation. In 2008, the alliance started selling imported cars in the metropolitan area of Mexico City, attracting customers with low prices and easy credit payments. However, sales suffered due to low acceptance of the models, as well as the 2008 crisis that reduced financing. Additionally, the cars did not comply with U.S. Safety and environmental standards, eliminating the possibility of exporting them to the United states. These factors raised questions about the viability of the assembly plant.

Thus, in 2009, Ricardo salinas found himself facing a dilemma: Whether to continue with the assembly plant or to stop importing and selling Chinese cars in Mexico.

Teaching objectives

The case can be used to cover several topics in strategic management and international business courses, such as business growth, international alliances, and crisis management. In the analysis of business growth, students can discuss the different options for taking advantage of market opportunities and diversifying across industries. In the study of alliance management, students can explore the benefits and difficulties in the creation of an alliance among developing-country firms, the complementarity between partners, and the divergence of objectives. In the analysis of crisis management, students can study the decision to stay with an existing strategic plan, change course and revise the plan, or follow a wait-and-see strategy in the face of an external economic crisis.

Discussion Questions

Business growth strategies:

- Why did Grupo salinas decide to enter the automobile industry? What were the benefits of this strategy? What were the limitations?

- Which alternative business strategy could have been implemented by Grupo salinas to sell automobiles?

- Why did Grupo salinas invest in the plant? What are the benefits and limitations of its location?

- Why did Grupo salinas seek an alliance? What were the benefits? What were the limitations?

- Were Chinese cars the best option? Was FAW the best option? What would you recommend?

- What are the options in the face of low sales levels? What are the benefits of each? What are the costs of each? Which one do you recommend?

International alliances:

Managing a crisis:

Conceptual Background

The main objective is to generate and discuss different perspectives on the process of growing via a strategic alliance for Grupo salinas and FAW amid a global crisis, and the impact that the introduction of Chinese cars could have on Mexico and its automotive industry. A secondary objective is deciding whether to maintain a strategy or change it.

Useful references to provide background concepts for the discussion are Hughes and Weiss (2007), Santora (2008), Williamson and Zeng (2009), and Kale and Singh (2009).

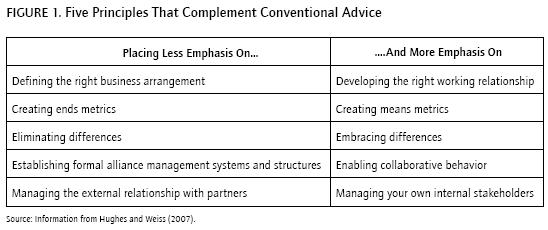

There are several points to discuss in partnerships like that between Grupo salinas and FAW. According to Hughes and Weiss, the conventional advice from the experts is quite consistent: "Focus on defining a business plan" or "Minimize conflict" (Figure 1).

Alliances pose special challenges that make traditional management practices irrelevant. These partnerships require two companies to cooperate with one another while simultaneously competing in the same market, and the participants must navigate often maddening differences in operating styles.

Hughes and Weiss (2007) recommend these practices for managing alliances:

1) Develop the right working relationship. Define exactly how you will work together. For example, clarify what "mutual trust and respect" means to each of you. Articulate how you will make decisions, allocate resources, and share information.

2) Peg metrics to progress. Alliances require time to pay off financially. Supplement "ends" metrics (financial performance indicators) with "means" metrics assessing factors that will affect the alliance's ultimate performance (such as information sharing and new-idea development).

3) Leverage differences. Companies ally to take advantage of partners' different know-how, markets, customers, and suppliers.

4) Encourage collaboration. When a problem arises (such as a missed milestone), replace finger-pointing with dispassionate analysis of how both parties contributed to it and what each can do to improve it.

5) Manage internal stakeholders. Most external alliances depend on cooperation from internal units in each partner company. Ensure that all internal players involved in supporting the alliance are committed to its success.

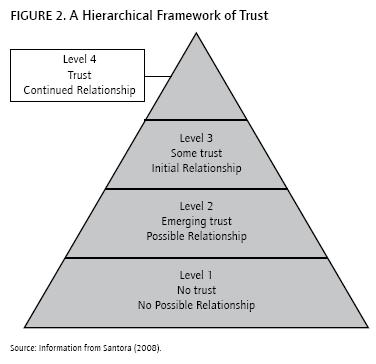

Adding to these ideas, santora's (2008) article mentions that a strategic alliance is a relationship between two or more companies that agree to conduct negotiations on trade, development, and fundraising with mutual relevant benefits. Trust is the initial condition for the development of a strategic alliance and the main point for construction and prosperity. Trust is the reliance of one person on another for his integrity, character, or skill. When trust between companies in not strong, the alliance moves directly towards failure (Figure 2).

Williamson and Zeng (2009) suggest that value for money has again become a strategic imperative, and not just because of the recession. In developing countries, consumers are traditionally value conscious. Many have entered the consuming class recently and have limited disposable Income. In the developing world, therefore, delivering value for money has become critical. What capabilities must companies possess to thrive in this environment? the authors suggest that instead of refining cost-cutting techniques, companies should develop cost-innovation capabilities. They must learn to reengineer their cost structures in novel ways so they can offer customers dramatically more for less. That may not be good news for many U.s., European, and Japanese corporations, which have usually dealt with low-cost competitors by going up-market and creating premium segments, both at home and abroad.

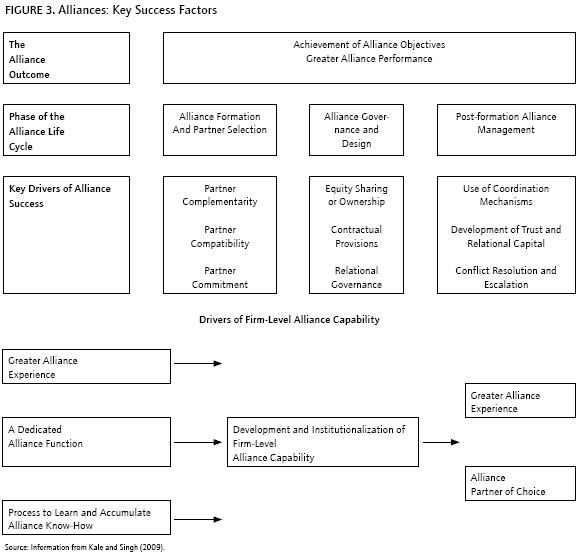

In the face of growing competition, the high rate of technological change, and discontinuities within most industries, firms pursue a large number of alliances to access new resources, enter new markets or arenas, or minimize their risk.

At the level of a single alliance of a firm, certain factors at each stage of the alliance life cycle are critical to alliance success (Figure 3). If a firm selects a complementary, compatible, and committed partner at the time of alliance formation, and makes relevant choices with respect to alliance design in terms of equity or contractual or relational governance, the alliance is more likely to succeed. During the post-formation stage, alliance success depends on the effective use of relevant coordination mechanisms to manage the interdependence between the two firms, and the successful development of trust between partners as the alliance evolves. Alliance capability requires attention to both a dedicated alliance function within a firm, and a set of institutionalized processes to accumulate and leverage alliance management know-how across the firm.

Analysis

This case shows the differences in objectives between the two companies in a strategic alliance. On the one hand, Mexico's Grupo salinas wants to grow its market base in the country's Base of the Pyramid (BoP), and on the other hand, the Chinese FAW group's interest is to expand its market presence in the United states through Mexico. This divergence of objectives is evident in the moment that an event that is exogenous to the business appears (the beginning of the global crisis in 2008). This shows that the commitment of both parties was not strong.

A firm like Grupo salinas needed to learn more about the effectiveness of this partnership and its abilities, as well as how to manage certain new types of alliances in new markets, generate incremental value by taking a portfolio approach to managing alliances, and realize gains by extending its alliance capabilities to become a relational organization that is adept at successfully managing other inter-firm relationships, including acquisitions.

Failure factors highlighted in the alliance between Grupo salinas and FAW:

1) The objectives did not seem consistent amid a global crisis and a market was not ready.

2) The constant communication and interaction between businesses was declining.

3) Neither of the parties had the ability to grow the mutual business.

In other words, alliances are not just fixed negotiations, but rather they require a high degree of independence between the companies, who must identify these differences between partners and ways of operation; these features form the common denominator in the handling of an alliance.

What happened to the Chinese cars? By 2010, Grupo salinas planned to support the Chinese cars sold, while FAW stopped the operations. The company said in its fourth quarter of 2009 report that the cost for the suspension of marketing of FAW cars was $276 million and it suffered the "plight of the global automotive industry".

Teaching plan

The teaching plan can be adjusted depending on the length of the class and the number of students, but the plan below is a suggestion.

Business growth strategies (30 minutes):

Start the discussion by identifying the reasons for diversifying into the automobile industry. The discussion can be organized on two sides of a whiteboard, with the pros on one side and the cons on the other. The decision seems to make little sense because the firm has no experience in automobiles or the infrastructure to sell them. However, the CEO seems to think it is a good opportunity and can use the experience of importing motorcycles from China to serve an underserved market segment. It is a new industry for the firm but the business group is used to managing diverse businesses and sees automobiles as a new growth opportunity. The experience with motorcycles was positive, but this worked well because Elektra already had a distribution infrastructure through which motorcycles could be sold. The problem with automobiles is that the company does not have the distribution in place and has to create a new distribution network, and they are higher priced items for which not only price but also perceptions of safety play a role in the purchase decision. In addition, low-income consumers can easily buy secondhand cars from the United states.

Then discuss the options for implementing the decision. The easiest way is importing Chinese cars; however, this is limited by regulation in Mexico against imports. Hence, the firm needs to consider producing cars. The next decision would be the location. If the objective of FAW is to export to the United states it would make more sense to produce near the U.s. border than in the center of the country. Hence the decision seems to be driven by the salinas Group and its desire to sell in Mexico and the rest of Latin America, as the location is well connected within Mexico, and to a port. This discussion of location can take place here, or later when discussing the alliance.

International alliances (20 minutes):

The second topic is the analysis of the needs of Grupo salinas and how these are met by a Chinese partner. The benefits of the alliance are that there are complementarities between the two firms-one has expertise in the country and the other has expertise in producing cars. Grupo salinas was actually looking for a Chinese partner and ended up with FAW when Geely was not available, thus raising questions about the commitment and interest of FAW to the success of the venture. FAW seems to see the investment as an entry point into the U.s. Market, while Grupo salinas seems to be interested in serving the Mexican and Latin American low-income segments, creating the potential for a conflict.

Managing a crisis (20 minutes):

The third topic is the analysis of decisions during a crisis. The economic crisis challenges the viability of the project, but it was already challenged by the inability to export to the U.s., which reduced the interest of the Chinese partner. Moreover, the low level of acceptance of the cars and the limited distribution network also affected the viability of the project. The "Made in China" label does have a negative connotation in the country, which may not be overcome by a low price since there are secondhand cars from the U.S. Market as alternatives to inexpensive new cars.

The traditional alternatives of continuing as planned, versus adapting to the new conditions, versus exiting, can be coached in terms of the voice, loyalty, and exit framework. The company can continue as planned. It could ask the government for support to bring the plant to success. Alternatively it can decide to wait and see how deep the crisis is and continue importing cars. However, this option is not viable because of the regulation of imports, which only allows for three years of tariff-free imports before beginning local production. The third alternative is to discard the plan of investing in the production plant. This does avoid the loss of the investment but it also limits the ability of the firm to grow in the market while still having to serve the previously sold cars in the future. The service could be outsourced to another company, but Grupo salinas would have to write off the investments in the network. For FAW, in contrast, the decision not to invest is less complicated. It has already benefitted from exporting cars for three years and learned about the Mexican market, while having few investments in the country. This discussion can be placed on the whiteboard in three columns, discussing the benefits and limitations of each. The recommendation depends on the value given to the reputation of the company and the understanding of whether past investments should determine future ones.

Conclusions (10 minutes):

The conclusions of the case can be a discussion of investment decisions under uncertain conditions and the need to analyze the potential of an investment opportunity for a particular company rather than the absolute benefit for any company.

References

Hughes, J., & Weiss, J. (2007). Simple rules for making alliances work. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 122. [ Links ]

Kale, P., & Singh, H. (2009). Managing strategic alliances: What do we know now, and where do we go from here? The Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(3), 45-62. [ Links ]

Santora, J. C. (2008). How to build a framework for strategic alliances. Nonprofit World, 26(6). [ Links ]

Williamson, P. J., & Zeng, M. (2009). Value-for-money strategies for recessionary times. Harvard Business Review, 87(3), 66-74. [ Links ]