Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Innovar

Print version ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar vol.25 no.57 Bogotá July/Sep. 2015

Marketing

Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v25n57.50356.

The Influence of Social and Environmental Labels on Purchasing: An Information and Systematic-Heuristic Processing Approach

La influencia de las etiquetas sociales y ecológicas (SE) en la decisión de compra: análisis de un enfoque sistemático-heurístico para el procesamiento de información

L'influence des labels sociaux et environnementaux (SE) dans la décision d'achat: analyse d'une approche systématique-heuristique pour le traitement de l'information

A influência dos rótulos sociais e ambientais sobre a compra: informação e processamento sistemático de abordagem heurística

Raquel Redondo PalomoI, Carmen Valor MartínezII, Isabel Carrero BoschIII

I Ph.D. en Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid, Madrid, España. Correo electrónico: rredondo@icade.comillas.edu

II Ph.D. en Marketing, Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid, Madrid, España. Grupo de Investigación E-SOST. Correo electrónico: cvalor@comillas.edu

III Ph.D. en Administración de Empresas Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid, Madrid, España. Grupo de Investigación E-SOST. Correo electrónico: icarrero@icade.comillas.edu

Correspondencia: Raquel Redondo Palomo. ICADE. Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid. c/ Alberto Aguilera 23, 28015 Madrid, España.

Citación: Redondo Palomo, R., Valor Martínez, C., & Carrero Bosch, I. (2015). The Influence of Social and Environmental Labels on Purchasing: An Information and Systematic-heuristic Processing Approach. Innovar, 25(57), 121-132. Doi: 10.15446/innovar.v25n57.50356.

Clasificación JEL: M30, M31, M14.

Recibido: septiembre 2012, Aprobado: mayo 2014

Abstract

This paper aims at exploring how social and environmental (SE) labels influence purchasing. By drawing on the information processing and the systematic-heuristic models, this study tests the process followed by consumers when purchasing SE labeled-products. Information was gathered through a structured questionnaire in personal interviews with 400 consumers responsible for household shopping of Fast-moving Consumer Goods (FMCG), who were randomly approached at shopping mails in four areas of Madrid, Spain. They were asked about recognition, knowledge, credibility, perceived utility and purchases on 12 different labels; the influence of these variables on purchase is modeled and tested by path analysis. This study suggests that a systematic-heuristic information processing occurs when consumers buy SE-labeled FMCG products, as the purchase of this type of goods depends on the recognition of a label, knowledge of the issue/issuer, as well as the credibility and the perceived utility of SE labels. Motivation for being informed influences the process, being an antecedent of awareness, comprehension and perceived utility. This model shows a dual processing mode: systematic and heuristic, where the lack of cognitive capacity could explain why these two processing modes co-occur. This paper adds value to existing literature on SE labels and consumption by applying the information processing model, which has not been used before in the field of responsible consumption, in addition to open a promising avenue for research, by offering complementary theories to the existing ones, based on attitudes.

Keywords: Responsible consumption, SE labels, dual processing, information processing model, systematic processing, heuristic processing.

Resumen

Este documento tiene como objetivo analizar la influencia de las etiquetas sociales y ecológicas (SE) en la decisión de compra de productos que portan esta marca distintiva. Con base en las teorías propuestas por el information processing model y el systematic-heuristic model, este trabajo analiza el proceso de compra de productos con etiquetas SE. Para la recolección de datos se empleó un cuestionario estructurado en entrevistas individuales que fue aplicado a 400 consumidores responsables de la compra de productos de consumo masivo en sus hogares, los cuales fueron seleccionados aleatoriamente mientras se encontraban en centros comerciales de cuatro puntos de la ciudad de Madrid, España. El instrumento preguntó a los consumidores sobre el reconocimiento del producto, conocimiento del contenido, la credibilidad, y la utilidad percibida para 12 marcas diferentes. El análisis de la influencia de las etiquetas en la decisión de compra se llevó a cabo usando el modelo de análisis de ruta (path analysis). Los resultados sugieren que la compra de productos social y ambientalmente sostenibles, es el resultado de la co-ocurrencia del procesamiento de información sistemático y heurístico dentro del consumidor, puesto que la decisión de compra de este tipo de productos se ve influenciada por el proceso de reconocimiento del producto, el conocimiento de su contenido, del ente emisor de la etiqueta y su credibilidad, y la utilidad percibida del producto. La motivación a estar informado se cuenta como un factor determinante dentro del proceso, al ser un antecedente de la conciencia, la comprensión y la utilidad percibida. El modelo propuesto muestra la existencia de un modo de procesamiento dual: sistemático y heurístico, en el que una limitada capacidad cognitiva podría explicar la co-existencia de estos dos modos de procesamiento de la información. En conclusión, el presente documento añade valor a la literatura sobre etiquetas sociales y ambientales y el consumo de los productos etiquetados, en cuanto aplica el modelo de procesamiento de información, el cual no había sido empleado en el análisis del consumo responsable. Adicionalmente, este trabajo abre las puertas a la investigación en el área estableciendo una teorización complementaria a las ya existentes, que se basan mayoritariamente en las actitudes del consumidor y no en el procesamiento de la información percibida.

Palabras clave: Consumo responsable, etiquetas sociales y ecológicas (SE), procesamiento dual, modelo de procesamiento de la información, modelo sistemático, procesamiento heurístico.

Résumé

Ce document vise à analyser l'influence des labels sociaux et environnementaux (SE) dans la décision d'achat de produits portant cette marque distinctive Basé sur les théories proposées par l'information processing model et le systematic-heuristic model, cet article analyse le processus de l'achat de produits avec des la-beis SE. Pour collecter les données on a employé un questionnaire structuré, au cours d'entretiens individuels, qui a été appliqué à 400 consommateurs responsables pour l'achat de produits de consommation destinés à leurs foyers. Ils ont été choisis au hasard alors qu'ils se trouvaient dans les centres commerciaux, en quatre points de la Ville de Madrid, en Espagne. L'instrument a interrogé les consommateurs à propos de la reconnaissance du produit, la connaissance du contenu, la crédibilité et l'utilité perçue de 12 marques différentes. L'analyse de l'influence des labels dans la décision d'achat a été réalisée en utilisant le modèle d'analyse de trajectoire (path analysis) Les résultats suggèrent que l'achat de produits socialement et écologiquement sou-tenabies est le résultat de la convergence du traitement systématique et heuristique des données par le consommateur, puisque la décision d'achat de ce type de produits est influencée par le processus de reconnaissance du produit, la connaissance de son contenu, de l'identité de l'émetteur du label et de sa crédibilité, et de l'utilité perçue du produit. La motivation d'être informé compte comme un facteur déterminant dans le processus, étant un précédent de la conscience, la compréhension et l'utilité perçue. Le modèle proposé montre l'existence d'un traitement bi-mode: systématique et heuristique, dans lequel une capacité cognitive limitée pourrait expliquer la coexistence de ces deux modes de traitement de l'information. En conclusion, ce document ajoute de la valeur à la littérature sur les labels sociaux et environnementaux et la consommation de produits ainsi marqués, en tant qu'il applique le modèle de traitement de l'information, qui n'avait pas été utilisé dans l'analyse de la consommation responsable. Par ailleurs, ce travail ouvre la porte à la recherche dans ce domaine, en éta-biissant une théorisation complémentaire à celles que existaient déjà, qui se basent pour la plupart sur les attitudes des consommateurs, mais pas sur Ie traitement de l'information perçue.

Mots-clés: Consommation responsable, labels sociaux et écologiques (SE), traitement dual, modèle de traitement de données, modèle systématique, traitement heuristique.

Resumo

Este trabalho tem por objetivo estudar a forma como os rótulos sociais e ambientais (SA) influenciam as compras. De acordo com o processamento de informações e a sistemática de modelos heurísticos, este estudo testa o processo seguido pelos consumidores quando compram produtos SA rotulados. As informações foram coletadas por meio de um questionário estruturado em entrevistas pessoais com 400 consumidores domésticos responsáveis por compras de produtos de consumo rápido (Fast Moving Consumer Goods - FMCG), os quais foram abordados de forma aleatória nos shopping centers de quatro áreas de Madri, Espanha. Eies foram questionados sobre o seu reconhecimento, conhecimento, credibilidade e utilidade de 12 diferentes rótulos, a influência dessas variáveis sobre a compra é modelada e testada por uma análise de percurso. Este estudo sugere que um processamento de informação heurística sistemática ocorre quando os consumidores compram os produtos FMCG SA rotulados, porquanto a compra destes depende do reconhecimento de um rótulo, o conhecimento da emissão ou o emitente e da credibilidade e utilidade percebida dos rótulos SA. A motivação para ser informado influencia o processo, sendo uma história de tomada de consciência, compreensão e utilidade percebidas. Esse modelo apresenta um modo de processamento duplo: a sistemática e a heurística, em que a falta de capacidade cognitiva poderia explicar por que razão esses dois modos de processamento ocorrem paraleiemente. Este trabalho contribui para a literatura existente sobre os produtos rotulados como SA e o consumo por meio da aplicação do modelo de processamento de informações que não tenham sido utilizadas antes no campo do consumo responsável. Aiém disso, abre uma via promissora para a pesquisa, a qual oferece teorias complementares para as já existentes, baseadas em atitudes.

Palavras-chave: Consumo responsável, rótulos SA, processamento duplo, mo-deio de processamento de informação, processamento sistemático, processamento heurístico.

Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR hereafter) is globally considered a source of competitive advantages as in the case of a higher customer loyalty or company reputation (Calabrese et al, 2013; European Commission, 2002; Webb et al., 2008). Putting into practice their CSR commitment, in the last few years, there are more firms offering responsible products and/or brands, including social and environmental (SE) attributes such as respect for workers' rights or the environment.

On the demand side, western consumers have gradually been including these SE attributes in their definition of ideal products (Cetelem, 2010; Forética, 2008; Manget et al, 2009; National Geographic & Giobescan, 2009). Following Roberts (1995) we define this type of consumers, also known as responsible or ethical consumers, as those "who purchase products and services which he/she perceives to have a positive (or less negative) impact on the environment or uses his/her purchasing power to express current social concerns".

Several authors have pointed out that given that social and environmental attributes are credence attributes that cannot be assessed before, during or after the purchase/ use of the product (Lupton, 2009), consumers need some aid to identify the responsible brands lying on the shelves. Social and environmental labels (hereafter SE labels), also called CSR labels, are considered the best way to signal that a product/brand matches the social and environ -mental expectations of consumers (De Peismacker et al., 2005; Fliess et al., 2007; Grail Research, 2009; Howard & Alien, 2006; Uusitaio & Oksanen, 2004). Labeled products/brands are also referred as ethical, responsible, social or environmental products/brands. To our knowledge, only two published papers have tried to build theories about this matter (De Peismacker & Janssens, 2007; McEachern & Warnaby, 2008). Both have applied the Theory of Planned Behavior in order to explain the influence of labels on purchasing behavior. In these models, attitudes are at the core being the key variables to explain behavior; however, research suggests that the impact of labels depends mostly on comprehension and trust (De Peismacker et al., 2005). Therefore, it seems that other theories, where information processing is at the core could well explain this issue.

In this paper, we apply the information processing and the systematic-heuristic processing models to explain how SE labels influence purchasing. We draw on the theoretical models developed to explain the efficacy of warning labels (in particular on the studies by Conzola & Wogalter, 2001; Wogalter & Laughery, 1996; Wogalter & Young, 1998) and on the Heuristic Systematic Modes (HSM) of information processing theory (Zuckerman & Chaiken, 1998). The HSM theory is applied here rather than the alternative, being very similar to the likelihood model elaboration (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), for two reasons: first, because only the HSM theory accepts that the two modes for information processing can coexist; and second, because this theory has been adapted to explain the influence on warning labels on consumers (Zuckerman & Chaiken, 1998). We posit that consumers must go through different stages, from awareness to understanding and acceptance, considering that if the process is interrupted at any of these stages, that is, if gaps occur, labels will not be effective as an information aid.

Previous research focused heavily on organic and fair trade labels, however, there is still a need for evaluating different types of SE labels (De Peismacker et al., 2005). Accord-ingly, this paper contributes to this research agenda by examining 12 SE labels found on FMCGs, which are among the products whose responsible purchasing is more likely to happen (Grail Research, 2009).

Background

The Information Processing Model

The information processing models, developed in the consumer psychology area and developed by advertising practitioners (Fennis & Stroebe, 2010), predict that a message has an impact on receivers' behavior if the information goes through different and sequential stages in the receivers' mind: attention or awareness, comprehension, acceptance, retention and behavior. Only if the information is correctly processed at each phase, will the message result in a behavioral change.

Theories on the influence of warning labels on consumers have suggested a systematic processing mode, based on a five-step model with three different stages: the cognitive stage, the affective stage and the behavioral stage. The cognitive stage comprises two steps: attention and comprehension.

For labels to influence a purchasing decision, consumers must notice them; if the label does not capture the attention of consumers, the process will stop. Some authors have highlighted the difficulties that consumers have when noticing labels, given that the penetration of labels is limited. "Labeled-CSR products typically represent niche markets accounting often for no more than 2% of consumption of the relevant category of products" (Fliess et al., 2007). This study found that even though label penetration among categories is increasing, their businesses' adoption is slow, and that penetration of standards among European countries varies greatly; for instance, the Ecolabel has 359 holders in Italy and 34 in UK (Ciroth & Franze, 2011).

Meanwhile, comprehension means that the consumer is able to understand label meaning. In SE labels, comprehension implies knowledge of issue and issuer, that is, knowledge of the issue or attribute protected by the label (e.g., animal welfare) and knowledge of the issuer of the label. Unless a search is run before purchasing, for a regular consumer it is difficult to know information such as the label-awarding body, the demands required to obtain them, or the differences among similar schemes.

Empirical research has shown that consumers are unsure as to what labels mean (Aspers, 2008; D'Souza et al., 2007; Iwanow et al, 2005; St0 & Strandbakken, 2005; Uusitaio & Oksanen, 2004), and despite the differences found across segments and types of labels, the high number of labels is seen as the main reason for consumer confusion (Langer et al., 2008), with more than one label for the same issue. Additionally, there are not any good label inventories (Fliess et al., 2007), but it is estimated that there are more than 200 only in Europe (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005).

Label design may also help increase (or decrease) the awareness and understanding on the product. No previous study has analyzed what kind of cues consumers use in order to build their knowledge, or what kind of label features could help increase their attention and comprehension. In relation to awareness, noticeable designs or large labels may attract consumer attention more than small or inconspicuous labels. Regarding comprehension, those labels whose design provide information about the awarding body or the issue covered will help consumers to understand its meaning and go on to the next phase of the information processing model.

As for the affective stage, it comprises two steps: trust and perceived utility. Receivers evaluate the credibility of the label and assess whether or not this information is useful for them (Wogalter & Young, 1998). This stage is affected by the consumers' beliefs and attitudes: labels must be coherent with consumers' attitudes; on this matter, surveys on Spanish consumers have found they demonstrate good attitudes toward responsible buying (CECU, 2008; Ce-teiem, 2010; Forética, 2008; Gallup Organization, 2009).

In the case of SE labels, believability depends on trust, that is, the credibility of the label for the consumer, which, in turn, is influenced by the credibility of the awarding body: when a label is backed up by an independent party (e.g., NGO or government), the credibility increases (Bonroy & Lemarie, 2008; De Peismacker et al, 2005; D'Souza et al, 2007; Langer et al, 2008).

It is worth mentioning that no published paper has identified the cues that consumers use to make a judgment about the credibility and the perceive utility of the label. Cliath (2007) analyzed the visual cues (of labels, among others) used by coffee brands to convey social and environmental information and compared them with the credibility of the standard used by the brand. She concluded that items other than the label were indicative of the manufacturer's honesty: the inclusion of realistic images of the production process, detailed contact information, country of origin, name of parent company or producer, panels with educational content, the inclusion of farmers' voices, among others. However, she did not test whether these are actually the cues employed by consumers to infer the quality of a label scheme.

Finally, even if consumers understand and trust labels, the purchase of SE labeled-products depends on perceived utility. If consumers find labels useful, it is more likely that they will buy this type of products.

Then, if consumers are aware of SE labels, understand their meaning, trust them, and are useful for them, they will purchase the labeled product. Therefore, we theorized that systematic information processing occurs when purchasing SE labeled products, reflecting this situation in the following hypotheses related to the information processing model:

H1a: There is a positive and direct relationship between awareness and label comprehension.

H1b: There is a positive and direct relationship between comprehension and trust.

H1c: There is a positive and direct relationship between trust and label utility.

H1d: There is a positive and direct relationship between utility and purchase.

However, there is a well-documented gap between the previous steps and actual behavior, a gap referred to in the literature as the attitude-behavior gap: consumers appreciate social and environmental labels but do not choose labeled products at the selling point. Different reasons have been provided for explaining why this gap occurs: higher prices, quality levels, sociai pressures, availability issues or just a desire for variety. All these factors explain why even highly ethical motivated consumers do not always buy brands with superior SE performance (Bennett & Williams, 2011; Carrigan et al., 2004; De Peismacker & Janssens, 2007; Iwanow et al., 2005; Mobley et al, 2010; Nicholls & Lee, 2006; Sampedro, 2003; Szmigin et al, 2009; Uusitalo & Oksanen, 2004).

The Systematic-heuristic Processing Model

The systematic information processing model needs to be complemented with the heuristic processing model, as suggested by Zuckerman and Chaiken (1998). The systematic-heuristic processing model establishes that there are two modes of information processing: systematic, linked to the information processing model explained above, where consumers seek, access, evaluate and integrate ail available information before making a judgment; and heuristic, where consumers use simple decision rules to make such a judgment.

The Systematic Process and the Motivation

Only when consumers recognize, understand and trust labels, they can produce simpler purchase decision rules. Then, the systematic processing mode applies to consumers that have the motivation and the cognitive ability to locate, process and integrate the information. Therefore, motivation becomes a key variable to explain the occurring of a systematic processing mode of purchasing. In the case of SE labels we posit that those consumers, for whom social and environmental attributes of a product/brand are key when making a purchase decision, will be more prone to doing the systematic processing mode.

Motivated consumers will be more aware of SE labels, as the selective attention theory suggests, their attention is guided by their concerns. If they are interested in SE attributes, they will notice them more than non-motivated consumers. Besides, it is plausible that they will have a deeper knowledge about SE labels: their motivation leads them to seek information about labels, read it, understand it and store it for later use. In addition, motivated consumers will find SE labels more useful: if they want to buy responsibly, SE labels will possibly be the only means to differentiate the brands on store shelves.

Therefore, we make the following hypotheses:

H2a: There is a positive and direct relationship between motivation and label awareness.

H2b: There is a positive and direct relationship between motivation and label comprehension.

H2c: There is a positive and direct relationship between motivation and label utility.

The Systematic Process and the Cognitive Ability

Consumers, even those strongly motivated, may lack the necessary cognitive ability for purchasing decision. This lack of cognitive ability is the main reason why one resorts to the heuristic processing mode. Two conditions may diminish this ability: lack of time and confusion. When consumers have limited time to do their shopping (Spanish consumers devote 3.3 hours per week to their grocery shopping) (MARM, 2010), their ability to process information, among other aspects, is curtailed. Confusion also reduces the cognitive ability to process information. As we explained before, confusion is prevalent in SE labels, due to the high number of labels, the difficulties in differentiating them and the obscure criteria and conditions to obtain each label. Involvement or motivation to buy responsibly does not reduce confusion (Langer et al, 2008). Moreover, consumers acknowledge being confused about other types of label1.

When consumers lack the cognitive ability, they will use heuristics, which involves simple cognitive decision rules to make judgments. In the case of SE labels, heuristics could be "if I see the logo of this NGO, I will buy it" or "if the label is green, it must be environmentally friendly". Then, an individual using heuristics will not sequentially go through every stage predicted in the information processing model; rather, once they understand an SE label, they will go directly/not to purchase the SE-labeled product, that is, they will directly link the cognitive and the behavioral stages, skipping the affective one.

Therefore, we posit that the heuristic processing model occurs and is reflected in the following hypothesis (Figure 1):

H3: There is a positive and direct relationship between comprehension and purchase.

Methodology

Study Design, Universe and Sample

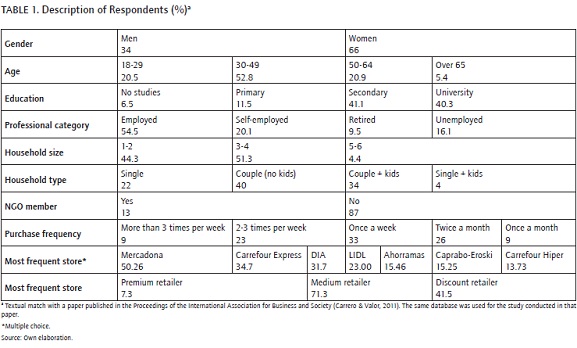

Information was gathered from a sample of main household buyers of FMCGs over 18 years old through structured personal interviews. Consumers were randomly approached at shopping mails in four areas of Madrid; these areas represent different economic strata. Out of the total, 400 valid interviews were obtained (sample error of 5.5% for p = q = 50%). A description of respondents is presented in Table 1.

Variables Used

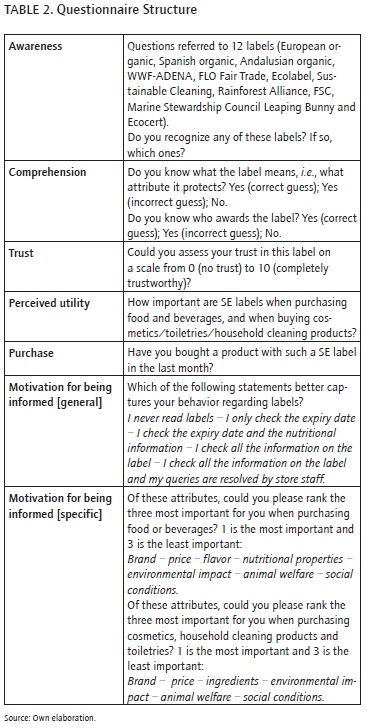

One of the main problems in studies of responsible consumption is the bias in seif-reported attitudes (Marchand & Walker, 2008; Newholm & Shaw, 2007; Van Doorn et al., 2007), which tend to be overrated. In this study, we tried to minimize the social desirability bias by formulating questions about past behavior (last month) and using projected questions, while avoiding questions about attitudes.

Attention/Awareness. Consumers were given a card with 12 SE graphic labels found in mainstream retailers in Ma-drid2. Then, they were asked whether they remembered seeing any of them.

Comprehension. For each label consumers recognized, they were asked if they knew the meaning of the label (or issue, for short) and the awarding body (or issuer). Interviewers were briefed about these labels and instructed to note down whether the consumer correctly guessed or not each of the answers, therefore differentiating between claimed knowledge and actual knowledge (following McEachern & Warnaby, 2008), which will allow us to infer confusion.

Trust. They were also asked to evaluate their trust in the recognized labels, by using a 10-point Likert scale.

Perceived utility. Consumers were asked to rate the influence of SE labels on purchasing decisions. In order to minimize the social desirability bias, respondents were asked first about the influence of these labels on an average consumer (projected question) and then about the perceived influence on their own purchasing decisions. We used the projected question in subsequent analyses, given that previous studies have highlighted the limited validity of self-reported behavior (Chao & Lam, 2011).

Purchase. Respondents were finally asked whether they had bought a product with such a label in the last month.

Studies in Spain (CEACCU, 2008) have shown that consumers are not able to understand the information on labels. Their ability to understand labels was evaluated as 3.9 over 10. Only 25% of buyers responded correctly to four questions on labels.

Motivation for being informed. First, we assessed the motivation to obtain information from labels creating an ordinal scale ranging from "I never read labels" to "I always read all the information and my queries are resolved by store staff. Second, we assessed the motivation to take into account social and environmental attributes when purchasing. Consumers were asked to rank the three most important attributes when buying products. Then, they were given a list of SE and non-SE attributes, following the suggestions by De Pelsmacker et al. (2005) to avoid the desirability bias. The order of attributes was rotated to avoid biases.

The summarized version of the questionnaire is shown in Table 2.

Analysis

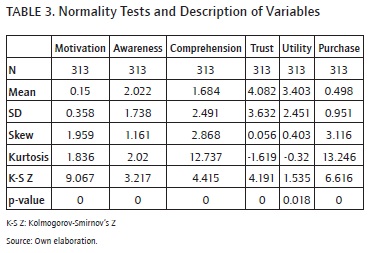

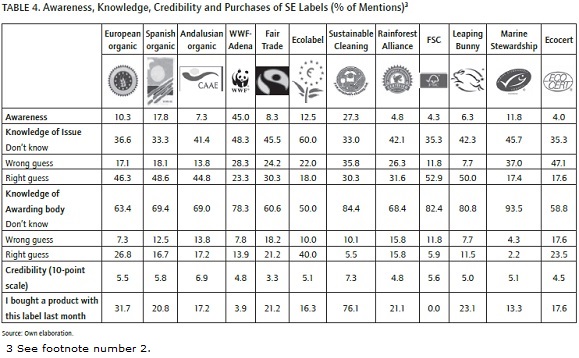

Path analysis was used to test the model. Initially, we tried model A for each of the specific labels. However, the reduced acknowledgement levels for certain labels (see Table 4) did not allow to estimate the model. Therefore, we calculated new variables aggregating the results for all labels, in order to obtain a parsimonious model (Batista-Foget & Coenders, 2000), as follows:

Awareness. Number of labels recognized (ranging from 0 to 12).

Comprehension. Mean of the variables Knowledge of Issue (number of labels whose issue is known - ranging from 0 to 12) and Knowledge of Issuer (number of labels whose issuer is known - ranging from 0 to 12).

Trust. Mean of credibility for the labels that each individual recognizes (ranging from 0 to 10).

Perceived utility of SE labels. Mean of the perceived utility of SE labels (ranging from 0 to 10).

Purchase. Number of labeled-products bought in the last month.

Motivation for being informed. T-tests and chi-square analyses showed that there is a relationship between motivation to read the labels, motivation to include social and environmental attributes in purchase decision, and NGO membership. NGO members tend to consult labels to a larger extent compared to non-NGO members (p-value < 0.05). For food/beverages and cosmetics/household cleaning products, members of NGOs include to a greater extent the three ethical attributes among their priorities (p-value < 0.05). Considering these results, we used NGO membership as a proxy for Motivation. Supporting this decision, other studies of Spanish consumers have also found that being an NGO member was a significant predictor of responsible consumption, more than gender, age or income (CECU, 2008).

The model was tested using the Generalized Least Squares (GLS) algorithm, which is considered more appropriate when variables are non-normal (Table 3) and when samples are small (Boomsma & Hoogland, 2001).

Given that is the first time that the information processing theory has been applied for explaining the purchase of SE labels, we have used path analysis with an exploratory and confirmatory purposes, by following the model development strategy (Hair et al., 1999; Kline, 1998). This strategy involves making adjustments on a baseline model, depending on the goodness-of-fit statistics. It entails a combination of inductive and deductive stages (Bollen, 1989).

We tested a first model (model A), analyzed the model fit measures, and used modification indexes and residual covariances to find modifications that could improve the model fit. This strategy, that was followed by other researchers in the field (e.g., McEachern & Warnaby, 2008), is valid as long as researchers provide the modification history and include changes supported by the theory (Hair et al., 1999).

Results

In model A, all estimates were significant (Figure 2), though this model fit was acceptable, but not good. Absolute fit (GFI) was 0.958 higher than the cut-off point of 0.9 (Hair et al., 1999; Levy & Varela; 2006) but RMSEA (0.121) was higher than 0.05-0.06 (Hair et al., 1999; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The indicators of incremental fit and parsimonious fit were lower than 0.9 (AGFI = 0.874, CFI = 0.842, NNFI = 0.662, and IFI = 0.848). However, R2 was relatively good (0.609), lower than the one obtained by McEachern and Warnaby (2008) in their study of responsible meat labels, but higher than other models developed to explain responsible behavior consumption (Shaw & Shiu, 2003; Kim & Damhorst, 1998).

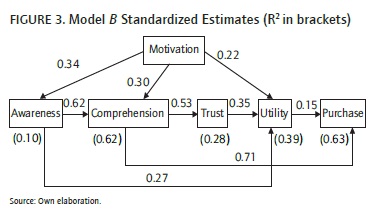

In order to improve the model fit, modification indices and standardized residual covariances were analyzed. They suggested the inclusion of a direct causal link from Awareness to Utility. This path is consistent with the theory, since it should be understood as a manifestation of the heuristic processing mode: noticing a label increases the perceived utility for the consumer, which will in turn influence purchase. Consequently, the new model (model B) was estimated (Figure 3).

The chi-square value for 6 degrees of freedom (13.352) and its significance (0.038) reveal that the data fit the model, and discrepancies are not significant at the 1% level. However, it is important to realize that this indicator demands normality, whereas the variables used are not normal.

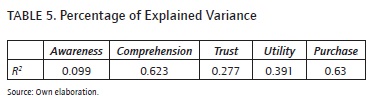

Absolute fit, incremental fit and parsimonious fit index values have notably improved. absolute fit (GFI) is now 0.986 and RMsEA (0.063) close to the good fit interval 0.05-0.06. However, some authors (e.g., Hu & Bentler, 1999) have found that RMsEA tend to over-reject true-population models with small sample sizes, so that this threshold must be understood as indicative (Batista & Co-enders, 2000). The incremental fit and parsimonious fit indices (AGFI = 0.950, CFI = 0.964, NNFI = 0.910, and IFI = 0.966) reveal very good fit, all of which are higher than 0.9. additionally, R2 is higher than in model A (0.630).

All the estimates in the model are statistically significant at the 99% cut-off value and the model is statistically acceptable as well. The estimates support the theoretical model proposed and hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d: purchase of SE-labeled FMCG goods depends on Awareness, Comprehension, Trust and Perceived utility. The strong and positive estimate linking Awareness and Comprehension (0.645) shows that Awareness is the antecedent of Comprehension (H1a). In addition, there is a positive and strong relationship between Comprehension and Trust (0.526) (H1b), between Trust and Utility (0.349) (H1c), and between Utility and Purchase (0,153) (H1d). However, the estimate linking Utility with Purchase, though significant, is yet weak. The reason for this low correlation will be explained in the Discussion section below.

A moderate and positive relationship was found between Motivation and Awareness (0.314): motivation positively influences Awareness (H2a). The direct effect of Motivation on Comprehension (H2b) and Perceived utility (H2c) is also significant (0.295 and 0.219, respectively). Motivation is, thus, an antecedent of the cognitive and the affective stage in the systematic process.

In addition, there is a direct and strong relationship between Comprehension and Purchase (0.712) and a direct link between Awareness and Utility (0.269), which supports H3 and suggests that both processing modes cooccur. Actually, the first relation has the strongest estimate in the path, and the second one, although it has a moderate regression weight, is critical for the model as it establishes the only difference with model A. This suggests that the heuristic processing mode is important in order to explain a purchase decision.

Additionally, the model's explanation for variances (Table 5) is acceptable (R2 is especially high for Comprehension and Utility).

Discussion

Findings presented in this research show that the information processing and the systematic-heuristic processing models could well explain the influence of SE labels on purchase. When processing information about SE labels, consumers follow a dual mode: a systematic mode (captured here in the information processing model) and a heuristic mode.

Consumers need to recognize, understand, trust and consider useful SE labels. This path is strongly influenced by motivation, that is, concern about the social and environmental attributes of a brand that triggers a systematic processing mode. Taking into account the limited information provided by the label, obtaining this knowledge probably entails seeking information outside the selling point (e.g., running online searches, asking friends, reading shopping guides, etc.). This information guides consumers' decisions about purchasing SE labeled products.

Nevertheless, a heuristic processing mode emerges whereby the mere recognition of a symbol leads to include the information conveyed in the label in the purchase decision, via a heightened perceived utility. Therefore, we presume that this path (awareness leads to purchase via perceived utility) would better fit those with incomplete knowledge, who would have not engaged in prior systematic information processing for decision-making.

This paper was not intended to find out why this dual processing occurs; yet, based on the systematic-heuristic processing theory, we posit that confusion about labels diminishes the cognitive ability of consumers and leads them to use heuristics.

Several signs of confusion can be identified in the data obtained. First, the percentage of consumers that correctly identified the meaning of the label (issue) and the awarding body (issuer) was significantly lower than those who recognized the logo; second, the relatively high percentages of claimed knowledge compared to actual knowledge. Consumers think they know, but they actually do not know the meaning or the awarding body, being this confusion more prevalent in certain labels (e.g., WWF, Fair Trade, and Sustainable Cleaning); third, although credibility is higher in labeling schemes backed up by government (e.g., Organic or Ecolabel) or social organizations (e.g., FSC or Leaping Bunny), the highest trust is placed on labels that are not issued by these institutions, but widespread in an industry (e.g., Sustainable Cleaning). There is no relationship between credibility and quality of the label.

Another key finding of this research, in line with theories of information processing, is the influence of motivation on the cognitive and affective stages, and consequently, on behavior; motivation is measured here with a proxy (membership of social organizations). Other studies have found that members of NGOs are cognitively empowered to a larger extent than non-members (Valor, 2008), and may provide consumers with information about labels. Besides, they exhibit a greater concern for buying ethical brands; yet, they will also use heuristics, as they also exhibit confusion.

In conclusion, this paper has found a gap between the cognitive and affective stages and behavior, that other previous studies have identified (Bennett & Williams, 2011; Carrigan et al., 2004; De Pelsmacker & Janssens, 2007; Iwanow et al., 2005; Mobley et al., 2010; Nicholls & Lee, 2006; Sampedro, 2003; Szmigin et al., 2009; Uusitalo & Oksanen, 2004). The sequence proposed by the information processing model is interrupted at the last step: the influence of perceived utility on purchase is limited. This leads us to think that other factors may influence purchase.

conclusions

This study has found that information processing theories and, more specifically, the systematic-heuristic processing theory could explain the purchase of SE labels. The model proposed here is parsimonious: it explains a large percentage of variance with a reduced number of variables. Likewise, the resulting model is very useful for practitioners: it shows the gaps, that is, on which variables to act upon in order to increase the effectiveness of labels.

In addition, this paper has found that a dual processing mode occurs, influencing the purchase of SE labeled-goods. Consumers engage in some systematic processing, whereby they seek, integrate and store information about labels. This process results in the recognition and comprehension of labels. However, for purchase to occur, consumers must also trust labels and regard them as useful for making purchase decisions. It is important to add that not all consumers will engage in the systematic processing mode, as motivation is a necessary condition. Heuristics, however, are based on the mere recognition of the label, as the recognition of a label leads to purchase indirectly via its positive influence on the perceived utility.

Moreover, this paper paves the way for a promising area of research in the field and builds up a research agenda to further examine this phenomenon. Future contributions should focus on three main issues: clarifying the processing modes, identifying the determinants of the variables used in the model, and merging them with other theories to include new variables in the model in order to better explain the phenomenon.

First, further studies should clarify the processing modes. It should be examined whether there are differences in the information processing label-wise and/or individual-wise. This should be oriented toward clarifying whether the same individual engages in different processing modes, and therefore, both modes coexist, and/or whether the same individual conducts different processing modes for different labels, or even for different product categories, issues of concern, or purchasing context. This would be useful as a basis for clustering consumers and labels. Second, future research should aim to unveil the determinants of the key steps in the information processing model. In particular, questions such as what builds awareness, what improves comprehension, how consumers infer the credibility of a label, and what creates and reduces confusion, should be directly addressed. Third, the information processing theories could be merged with other responsible consumer theories to better explain the phenomenon. In particular, the model used here could be improved by taking variables from the Theory of Planned Behavior, outlined by Ajzen (1985, 1991), which is the dominant theoretical framework to explain responsible consumption.

Pie de página

1 Studies in Spain (CEA CCU, 2008) have shown that consumers are not able to understand the information on labels. Their ability to understand labels was evaluated as 3.9 over 10. Only 25% of buyers responded correctly to four questions on labels.

2 Information taken from the inventory conducted by Valor and Calvo (2009). All the labels were certified by an independent body (NGO, government or industry association).

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: J. Kuhl, & J. Beckman (Eds.). Action-control: From cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Special Issue: Theories of Cognitive Self-Regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. [ Links ]

Aspers, P. (2008). Labeling fashion markets. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(6), 633-638. [ Links ]

Batista, J.M., & Coenders, G. (2000). Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales: modelos para el análisis de relaciones causales. Madrid: La Muralla. [ Links ]

Bennett, G., & Williams, F. (2011). Mainstream green. New York: Ogilvy & Mather. [ Links ]

Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Bonroy, O., & Lemarie, S. (2008). Downstream Labeling and Upstream Competition. Working Paper GAEL 2008-06. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Université Pierre Mendès, France. [ Links ]

Boomsma, A., & Hoogland, J.J. (2001). The robustness of LISREL modeling revisited. In: Cudeck, R., du Toit, S., & Sõrbom, D. (Eds.). Structural equation modeling: Present and future: A Festschrift in honor of Karl Jõreskog. Chicago: Scientific Software International. [ Links ]

Calabrese, A., Costa, R., Menichini, T., Rosati, F., & Sanfelice, G. (2013). Turning CSR-Driven Opportunities in Competitive Advantages: a Two-Dimensional Model. Knowledge and Process Management, 20(1), 50-58. [ Links ]

Carrero, I., & Valor, C. (2011). Slaves of Market Information: The Relationship Between Spanish Consumers and CSR Labels. Proceedings of the International Association for Business and Society 2011. [ Links ]

Carrigan, M., Szmigin, I., & Wright, J. (2004). Shopping for a better world? An interpretive study of the potential for ethical consumption within the older market. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(6), 401-417. [ Links ]

CEACCU (2008). ¿Sabemos lo que comemos? Available at: http://www.ceaccuorg/component/docman/doc.../174-sabemos-lo-que-comemos-. [accessed 1 June 2011] [ Links ].

CECU (2008). La opinión y valoración de los ciudadanos sobre la Responsabilidad Social de la Empresa en España. Madrid: ROELMA S.L. Available at: http://www.cecu.es/GuiaRSE3.pdf [accessed 1 June 2011] [ Links ].

Cetelem (2010). L'Observatoire Cetelem 2010: Consommer en 2010. Pas moins, mais mieux. Available at: http://observatoirecetelem.com/medias/pdf/france/2010/observatoire_cetelem_2010_les_marches_francais.pdf [accessed 4 March 2010] [ Links ].

Chao, Y.L., & Lam, S.P. (2011). Measuring responsible environmental Wogalter, M.S. (2001). A communication-human information processing (C-HIP) approach to warning effectiveness in the workplace. Journal of Risk Research, 4(4), 309-322. [ Links ]

D'Souza, C., Taghian, M., Lamb, P., & Peritatko, R. (2007). Green Decisions: Demographics and Consumer Understanding of Environmental Labels. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(4), 371-376. [ Links ]

De Pelsmacker, P., Janssens, W., Sterckx, E., & Mielants, C. (2005). Consumer preferences for the marketing of ethically labelled coffee. International Marketing Review, 22(5), 512-530. [ Links ]

De Pelsmacker, P., & Janssens, W. (2007). A model for fair trade buying behaviour: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 361-380. [ Links ]

European Commission (2002). CSR: a Business Contribution to Sustainable Development. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/soc-dial/csr/index.htm [accessed 21 March 2010] [ Links ].

Fennis, B.M., & Stroebe, W.S. (2010). The psychology of advertising. New York: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Fliess, B., Lee, H.J., Dubreuil, O.L., & Agatiello, O. (Eds.) (2007). CSR and Trade: Informing Consumers about Social and Environmental Conditions of Globalised Production. OECD Trade Policy Working Paper No. 47. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/tad. [ Links ]

Forética (2008). Informe Forética 2008. Evolución de la responsabilidad social de las empresas en España. Available at: http://www.foretica.es/recursos/doc/Biblioteca/Informes/36900_16121612200821230.pdf [accessed 20 April 2010] [ Links ].

Gallup Organization (2009). Eurobarometer: Europeans attitudes towards the issue of sustainable consumption and production. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_256_en.pdf [accessed 1 April 2010] [ Links ].

Grail Research (2009). The Green revolution. Available at: http://www.grailresearch.com/pdf/ContenPodsPdf/The_Green_Revolution.pdf [accessed 9 June 2011] [ Links ].

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black, W.C. (1999). Análisis Multivariante. Madrid: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Howard, P.H., & Allen, P. (2006). Beyond organic: consumer interest in new labelling schemes in the Central Coast of California. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(5), 439-451. [ Links ]

Hu, L., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55. [ Links ]

Iwanow, H., McEachern, M.G., & Jeffrey, A. (2005). The Influence of Ethical Trading Policies on Consumer Apparel Purchase Decisions. A Focus on the Gap Inc. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 3(5), 371-387. [ Links ]

Kim, H.S., & Damhorst, M.L. (1998). Environmental concern and apparel consumption. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 16(3), 126-133. [ Links ]

Kline, R.B. (1998). Principles and practice of Structural Equation Modelling. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Langer, A., Eisend, M., & KuB, A. (2008). The Impact of Eco-Labels on Consumers: Less Information, More Confusion? European Advances in Consumer Research, 8, 334-335. [ Links ]

Levy, J.P., & Varela, J. (2006). Modelización con estructuras de covarianzas en ciencias sociales. Madrid: Netbiblo. [ Links ]

Lupton, S. (2009). Fair trade and signaling: information and illusion. Working Paper MPRA No. 14560, Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Available at: http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/14560. [ Links ]

Manget, J., Roche, C., & Münnich, F. (2009). Capturing the Green Advantage for Consumer Companies. BCG. Available at: http://www.bcg.com/documents/file15407.pdf [accessed 22 December 2009] [ Links ].

Marchand, A., & Walker, S. (2008). Product development and responsible consumption: Designing alternatives for sustainable lifestyles. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(11), 1163-1169. [ Links ]

MARM- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Medio Rural y Marino (2010). Estudio de mercado Observatorio del Consumo y la Distribución Alimentaria. Available at: http://www.marm.es/es/alimentacion/temas/consumo-y-comercializacion-y-distribucion-alimentaria/informe_10_tcm7-8051.pdf [accessed 18 December 2011] [ Links ].

McEachern, M.G., & Warnaby, G. (2008). Exploring the relationship between consumer knowledge and purchase behaviour of value-based labels. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(5), 414-426. [ Links ]

Mobley, C., Vagias, W.M., & DeWard, S.L. (2010). Exploring additional determinants of environmentally responsible behavior: The influence of environmental literature and environmental attitudes. Environment and Behavior, 42(4), 420-447. [ Links ]

National Geographic and Globescan (2009). Greendex 2009: Consumer Choice and the Environment- A Worldwide Tracking Survey. Available at: http://www.nationalgeographic.co.in/greendex/assets/GS_NGS_Full_Report_May09.pdf [accessed 23 November 2009] [ Links ].

Newholm, T., & Shaw, D. (2007). Studying the ethical consumer: A review of research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 6(5), 253-270. [ Links ]

Nicholls, A., & Lee, N. (2006). Purchase decision-making in fair trade and the ethical purchase gap: is there a fair trade twix? Journal of Strategic Marketing, 14(4), 369-386. [ Links ]

Petty, R.E., & Cacioppo, J.T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag. [ Links ]

Roberts, J.A. (1995). Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer http://webs.uvigo.es/consumoetico/textos/archivos_pdf/consumoetico.pdf [accessed 3 May 2011] [ Links ].

Shaw, D., & Shiu, E. (2003). Ethics in consumer choice: a multivariate modeling approach. European Journal of Marketing, 37(10), 1485-1498. [ Links ]

St0, E., & Strandbakken, P. (2005). Ecolabels and Consumers. In: Rubik, F., & Frankl, P. (Eds.). The future of Ecolabeling. Making Environmental Product Information Systems Effective. London: Greenleaf Publishing. [ Links ]

Szmigin, I., Carrigan, M., & McEachern, M.G. (2009). The conscious consumer: Taking a flexible approach to ethical behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(2), 224-231. [ Links ]

Uusitalo, O., & Oksanen, R. (2004). Ethical Consumerism: A View from Finland. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 28(3), 214-221. [ Links ]

Valor, C. (2008), Can consumers buy responsibly? Analysis and solutions of market failures. Journal of Consumer Policy, 31(3), 315-326. [ Links ]

Valor, C., & Calvo, G. (2009). Compra responsable en España. Comunicación de atributos sociales y ecológicos. Distribución y Consumo, Boletín Económico 2971, 33-50. [ Links ]

Van Doorn, J., Verhoef, P.C., & Bijmolt, T.H.A. (2007). The importance of non-linear relationships between attitude and behaviour in policy research. Journal of Consumer Policy, 30(2), 75-90. [ Links ]

Webb, D.J., Mohr, L.A., & Harris, K.E. (2008). A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. Journal of Business Research, 61 (2), 91-98. [ Links ]

Wolgater, M.S., & Laughery, K. (1996). Warning! Sign and label effectiveness. Current Decisions in psychology, 5, 33-7. [ Links ]

Wogalter, M.S., & Young, S.L. (1998). Using a hybrid communication/ human information processing model to evaluate beverage alcohol warning effectiveness. Applied Behavioral Science Review, 6(1), 17-37. [ Links ]

Zuckerman, A., & Chaiken, S. (1998). A heuristic-systematic processing analysis of the effectiveness of product warning labels. Psychology and Marketing, 15(7), 621-642. [ Links ]