Introduction

Digital technology has democratized the power to share stories. Although social networking sites (SNS) offer simple ways for brands to communicate with consumers, the number of messages and other stimuli makes it challenging to effectively get the message across. Storytelling is one of the strategies used to increase the efficacy of communication and encourage consumer involvement with brands, particularly in SNS, and thus to overcome information overload and negative attitude towards advertising (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019). As defined by Serrat (2017), storytelling is:

The vivid description of ideas, beliefs, personal experiences, and life-lessons through stories or narratives that evoke powerful emotions and insights. It refers to the use of stories or narratives as a communication tool to value, share, and capitalize on the knowledge of individuals. (p. 839)

Stories help to connect and remember. Across centuries, people enjoy telling stories and listening to storytelling (Bassano et al., 2019). When adopted by brands, storytelling can help developing customer relationships, providing topic and meaning to conversations (Gensler et al., 2013; Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010). Serrat (2017) suggests that the advantages of this digital communication strategy include: (i) enabling articulation of emotional aspects as well as factual content, hence allowing expression of tacit knowledge (which is particularly difficult to convey); (ii) providing a broader context in which knowledge arises, increasing the potential for meaningful knowledge-sharing; and (iii) increasing the likelihood that learning will take place and will be passed on. Some authors add that storytelling reinforces the construction of emotional ties, recognition, memorability, and personal identification with the brand (e.g., Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010; Zollo et al, 2020).

It is therefore no wonder that storytelling deserves increasing attention from marketers, being used by brands to communicate value propositions, personality, identity, and to increase brand awareness. The phenomenon itself is not new. What is new is that the contribution of the digital age has amplified, facilitated, and made this phenomenon more notorious (Copeland & de-Moor, 2018; Escalas, 2004; Escalas & Stern, 2003; Gensler et al., 2013; Hollebeek & Macky, 2019; Pera & Viglia, 2016; van-Laer et al, 2019) to the benefit of brands.

One of the reasons for the popularity of digital storytelling campaigns through SNS is the fact that it offers mechanisms for the development and management of customer relationships (de-Vries et al., 2012). Digital storytelling not only helps connect brands with customers and prospects but also plays a crucial role in transforming experiences and developing advocacy (Chronis, 2005; McCabe & Foster, 2006). The branding literature has long recognized the power of storytelling to provide brand meaning, while practitioners have used storytelling to enhance consumers' connections with brands (Brown et al., 2003; Escalas, 2004; Megehee & Woodside, 2010; Singh & Sonnenburg, 2012; Woodside et al, 2008).

Nevertheless, the existing literature, particularly on digital level, is still scarce. A search by the keywords "digital storytelling" and "brand" in Scopus database showed only 16 results between 2010 and 2019. The last year (2019) showed a clear increase (6 articles published), despite the numbers continuing low. At Web of Science database the scenario is similar, with only 5 results from the same query ("digital storytelling and "brand"), ranging from 2012 to 2019. Consequently, there is a clear research gap regarding the factors that explain the impacts of digital storytelling strategies on brands. In order to help practitioners developing effective digital storytelling strategies, there is a need to better understand the impact of digital storytelling campaigns, namely regarding attitudes and perceptions towards brands and on the behavior of consumers, in general, and young consumers, in particular.

Indeed, the generations that use SNS more intensively are the younger. Generation Y (born 1978-1994) is known as the generation of Facebook, and Generation Z (born 1995 onwards) is known as "Net Gen," the generation that fully integrated the Internet into their daily lives (Williams & Page, 2011). The impact of communication campaigns on SNS over millennials is widely acknowledged. Members of these two generations were born, grew up, and currently live in the digital age, where the internet and the SNS are an integral part of their lives. As such, their digital interaction with brands is a very important field of study, which was also considered by this article.

This article focuses on digital storytelling as brand content strategy (Escalas, 2004), aiming to contribute to a greater understanding of the outcomes shared in the SNS, and thus highlight the factors that increase its effectiveness amongst young consumers. For the purpose of this article, customer interaction with branded content in SNS comprises liking, commenting, and sharing. The article also focus on the development of brand-customer relationships, from emotional bonding to brand loyalty.

Overall, this article provides several contributions. First, an updated reflection on the use of storytelling in social media marketing and communication strategies. Despite the popularity of the topic among practitioners, its literature is scattered, and the focus provided in this article regarding consumer behavior and the impact on brands offers an interesting framework that can be used by other researchers. The article also provides anecdotal evidence of in-depth first-hand views of consumers related to examples of digital storytelling campaigns, offering support to points made by extant literature but also providing new insights on how storytelling campaigns are perceived and their expected impacts on brands and consumer behavior. Combining both the contributions in extant literature and the findings of the qualitative study, this article presents a synthesis of the factors that explain interaction with digital storytelling campaigns and the outcomes for their associated brands. In general, this article demonstrates the relevance of further studying digital storytelling and provides valuable cues for managers considering adopting this strategy, including alerts regarding risks related to possible lack of consistency between the issues approached in the campaign and the characteristics of the brand.

The following pages present the main contributions of the literature on digital storytelling, which served as the basis for proposing two research questions as presented in the method: (RQ1) What are the determinants of users' interaction with storytelling campaigns on SNS?, and (RQ2) How do storytelling campaigns on SNS affect brands? In order to tackle the two research questions, the authors conducted a qualitative empirical study, comprising 8 focus groups with a total of 40 Portuguese consumers aged 19 to 37. Results provide anecdotal evidence of the impacts of digital storytelling campaigns in young consumers' behavior and interesting cues particularly for marketing and communication practitioners.

Background

Throughout the ages, the art of storytelling has been used as a method for creating emotional connections. From our ancestors to present days, the popular tradition of telling stories has never been lost, and there is a reason for these to continue to be told and remembered. A story is a description of an event (or a series of events) which will lead to a transition from the initial state to the later state or outcome (Bennett & Royle, 2016). Generally, narratives are the most powerful and lasting strategies for sharing information, knowledge and values, passed down through generations. The emergence of the internet and the latest advances in information and communication technologies have brought new ways of being socially and professionally connected, leading to the emergence of digital marketing and digital content strategies. And this gave rise to brand usage of digital storytelling tools to capture consumers' attention.

Storytelling as a marketing and communication strategy

The power of stories in marketing and communication has long been recognized by managers (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019; Gensler et al., 2013), who adapt storytelling strategies to convey marketing messages and branded content in order to influence customers' perceptions, feelings and behavior (Escalas, 2004; van-Laer et al, 2014). As explained by Dessart and Pitardi (2019), the storytelling narrative structure has two essential strategic components: chronology and causality. While chronology conveys a temporal dimension to the story (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019), helping the public to clearly identify its stages (beginning, middle, and end), causality adds causal inferences to the events presented in the story, enabling the establishment of causal relationships among its elements (Escalas, 1998). In addition, storytelling often uses emotional appeals designed to stimulate listeners and to trigger higher levels of emotional involvement with the story (Brechman & Purvis, 2015). As noted by Pera and Viglia (2016), moral gist is particularly important, as stories that focus on a "lesson learned" are deemed more impactful to the audience. Furthermore, autenticity is also an essential feature, as it fosters audience trust and story acceptance (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019), and thus increase audience involvement and engagement.

Brand content strategies, such as brand storytelling, are increasingly used in an attempt to get the attention of customers and prospects (Maslowska et al., 2016). Brand content has been studied in how it is deployed and broadcasted, using parameters such as the timing of the broadcast, its interactivity, and the type of information it conveys (Lee et al., 2018; Schultz, 2017). Yet, beyond these practical aspects, the digital strategies used to foster long-term customer relationship and brand loyalty are complex. Effective digital campaigns require high degree of creativity (Ashley & Tuten, 2015) and often involve the development of a storyline around the brand (Pera & Viglia, 2016). Hollebeek and Macky (2019) go as far as to suggest that true brand content inherently tells a brand's story, hence suggesting that storytelling is ineherent to all brand communication. Moreover, Dias and Dias (2018) found that product narratives can be regarded as a new level of product extension -an inspirational layer. It creates an identification with the product, and leads customers and potential customers to appropriate the products for their own self-expression (Kornberger, 2010).

Brand storytelling corresponds to the moment of producing stories and storylistening corresponds to the moment of consumption of the stories, which nourishes the virtuous circle of place identity definition for positioning or repositioning the brand (Bassano et al., 2019). Digital storytelling is a feature of storytelling that differs essentially by how it is shared and by the media used (Dias & Dias, 2018; Zollo et al., 2020). Miller (2004) describes digital storytelling as narrative entertainment that reaches its audience via digital technology and media -microprocessors, wireless signals, the web, and so on-, which can support interactivity. Burgess (2006) and Zollo et al. (2020) highlight the importance of the collaborative social interaction, which arguably is what truly defines digital storytelling.

As a result of the above, digital storytelling is a strategy to share experiences, recognition, emotions, and values (Dias & Dias, 2018) that has long been applied as a core method for brands to achieve expected marketing effects such as attracting and retaining customers. Telling a story can influence attitudes, intentions, and behaviors (Baldwin & Ching, 2017; Escalas, 2004; Spiller, 2018). Hence, digital brand storytelling is related to the processes for increasing the communicative value of brand, as well as brand identity, over the internet technologies.

Expected impacts on consumer behavior

When storytelling campaigns are used in SNS they have certain effects for the brand, such as the impact on their awareness or facilitating the development of the relationship with the customer. Brand awareness can then be understood as the level of recognition of a brand by potential consumers (Bassano et al., 2019; Dias & Dias, 2018; Li et al, 2019). SNS represent a way of exposing consumers to the brand, thus creating awareness for the brand. It is known that the more actively consumers interact with a brand's SNS activities, the greater the brand awareness (Hutter et al., 2013). So, the value of digital storytelling as a central tool for communicating the experiential value of a brand should be given greater recognition (Bassano et al., 2019).

Several authors (e.g., Li et al., 2019; Schembri & Latimer, 2016) show that storytelling can effectively build customer trust. One of the aspects that have been deserving attention by these authors is which the characteristics of "storytelling" are especially important to build trust. Li et al. (2019) found that storytelling could increase consumer trust if the story is made relevant to consumers, offers concrete details and eye-catching videos or audios, and promotes positive values.

Overall, the literature points out that persuasiveness is higher in the case of storytelling advertising as compared to traditional argument-based advertising, due to its ability to generate positive feelings, trigger imagery, and holding the attention of the audiences (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019, Escalas, 2004; van-Laer et al, 2014). Others suggest that digital storytelling enhances engagement with the brand, loyalty, and recommendations (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019; Dias & Dias, 2018; Faraoni et al, 2019). In general, digital storytelling advertising is expected to have a better performance in influencing the desired consumer (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019, Escalas, 2004; van-Laer et al, 2014). The emotional responses generated by digital storytelling include positive feelings and emotions (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019) and empathy (Escalas, 2004; Escalas & Stern, 2003). On this regard, Escalas (2004) suggests that the emotional bonding may result from connections between storytelling narratives and personal experiences. In fact, the audience tends to use personal experiences to interpret, understand, and judge the the story conveyed in the ad (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019).

De-Vries et al. (2012) demonstrated that customer interaction with brand posts on SNS depends on the characteristics of a post (e.g., message vividness and interactive nature) but also on its popularity (e.g., number of likes, number of comments). In fact, Hinz et al. (2011) found that popular posts in terms of the number of likes are the ones users share the most. Some authors point out altruism, social interaction, economic incentives, and self-worth and personal growth enhancement as the reasons for sharing posts online (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004; Ho & Dempsey, 2010). The resulting word-of-mouth communication may be considered a manifestation of customer engagement and brand promotion (Cheung & Thadani, 2012; Chu & Kim, 2011; Dessart & Pitardi, 2019; Farace et al, 2017; Hennig-Thurau et al, 2004; Hennig-Thurau & Walsh, 2003; Rialti et al, 2017).

In conclusion, the studied found in the literature indicate that digital brand storytelling enables a strategic communication process and contributes to building sustainable competitive advantage and long-term relationships with customers.

Method

Based on the contributions to the literature on the field, two research questions were proposed for this study.

RQ1: What are the determinants of users' interaction with storytelling campaigns on sns?

The literature points out that interaction will depend on the characteristics of the content, such as creativity (Ashley & Tuten, 2015), the ability to trigger emotions (Brechman & Purvis, 2015) and perceived authenticity (Pera & Viglia, 2016). Post popularity on SNS is also expected to increase content interaction (de-Vries et al., 2012; Hinz et al, 2011).

RQ2: How do storytelling campaigns on sns affect brands?

Digital storytelling campaigns are expected to have a strong impact on consumers, namely on their emotions (Dias & Dias, 2018; Escalas, 2004), thus building customer trust (Li et al., 2019; Schembri & Latimer, 2016), affecting their perceptions, attitudes, intentions and behaviors (Baldwin & Ching, 2017; Escalas, 2004; Spiller, 2018; van-Laer et al., 2014), and increasing brand loyalty and e-loyalty (Brechman & Purvis, 2015; Faraoni et al., 2019; Rialti et al, 2017). As such, the impacts on brands include increase brand recognition and awareness (Dias & Dias, 2018), attracting and retaining customers (Dias & Dias, 2018; Maslowska et al., 2016), and increasing brand engagement and interaction (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019; Dias & Dias, 2018; Zollo et al, 2020). Therefore, digital storytelling is particularly recommended for brand positioning (Bassano et al, 2019) and differentiation strategies (Dias & Dias, 2018), being expected to provide competitive advantages.

In order to tackle the two research questions proposed by this study, a qualitative and exploratory approach was adopted, using focus groups to collect data. To initiate the discussion, the videos of three digital storytelling campaigns were watched by participants. Chosen campaigns had been recently disseminated on SNS, corresponding to a cause, a service, and a product.

The first campaign shown is called "A storybook wedding,"1 launched by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) in 2016. This campaign contains a slight plot twist, showing the preparations for a wedding while giving tips for its final resolution. It addresses the theme of child marriage, showing that the bride is a child. At the end, it shows an informative text on the number of female children who get married each year and asks viewers to share the campaign.

The second campaign was "Christmas Vodafone 2017,"2 launched by Vodafone before Christmas 2017. The theme addressed in the campaign is bullying, which is shown to the viewer through a boy who walks in the school choir and when rehearsing reveals his skills as a singer, although his classmates laugh and make fun of him. The story develops showing the difficulties that the teenager goes through, while his colleagues keep harassing him, until one of them sees the boy crying in the bathroom. The story ends with the choir recital, in which other choir members let the teenager shine and show his talent, and for that, they use smartphones. The video ends with the female voice-over saying "The best you have, will inspire the world. Merry Christmas! Vodafone."

The third campaign watched by participants was "A man like you,"3 released by Harry's in 2018. This campaign has a slight plot twist, presenting the adventure of a young boy who meets an extraterrestrial in the field and is asked what it means to be a man. Several situations arise, some of humorous content, others that denounce that something might be going wrong in the boy's life. During these situations, the boy explains the extraterrestrial what it is like to be a man after all, using examples such as "A man likes cars and sports," stereotypes used frequently when addressing gender issues. The campaign continues with the reflection that a man can be who and what he wants, and almost at the end shows the viewer that the extraterrestrial never existed and was just a child's mental creation. The boy had lost his father and was trying to deal with this loss while trying to understand his role and giving emotional support to his mother. The campaign ends by introducing Harry's brand and identifying it as a brand for all men.

Participants in this research consisted of young Portuguese adults, aged 18 to 37, who were SNS active users. The focus groups were based on purposive samples (Morgan, 1996), carrying out a total of 8 focus groups, which enabled reaching data saturation. The constitution of the groups is shown in table 1.

Table 1 Focus groups' participants.

| Group | Age range | Gender | Education | Marital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21-37 | Female: 4 Male: 1 | 12th year: 2 Bachelor: 3 | Single: 4 Married: 1 |

| 2 | 21-37 | Female: 3 Male: 2 | 12th year: 4 Bachelor: 1 | Single: 4 Married: 1 |

| 3 | 19-20 | Male: 5 | 6th year: 1 11th year: 1 12th year: 3 | Single: 5 |

| 4 | 19-32 | Female: 4 Male: 1 | 6th year: 1 12th year: 4 | Single: 5 |

| 5 | 21-36 | Female: 3 Male: 2 | 6th year: 2 9th year: 3 | Single: 4 Divorced: 1 |

| 6 | 22-26 | Female: 4 Male: 1 | Bachelor: 2 Master: 3 | Single: 5 |

| 7 | 22-37 | Female: 4 Male: 1 | Bachelor: 3 Master's degree: 2 | Single: 4 Married: 1 |

| 8 | 19-21 | Female: 5 | 12th year: 4 Bachelor: 1 | Single: 5 |

Source: authors.

The focus groups were conducted following the same outline composed of three questions: (i) What do you think about these campaigns? Can you please talk about them, share your opinions?; (ii) What were your reactions when you saw these campaigns on your feeds in SNS?; (iii) Can we further discuss the brands in the campaigns? What do you think of them?

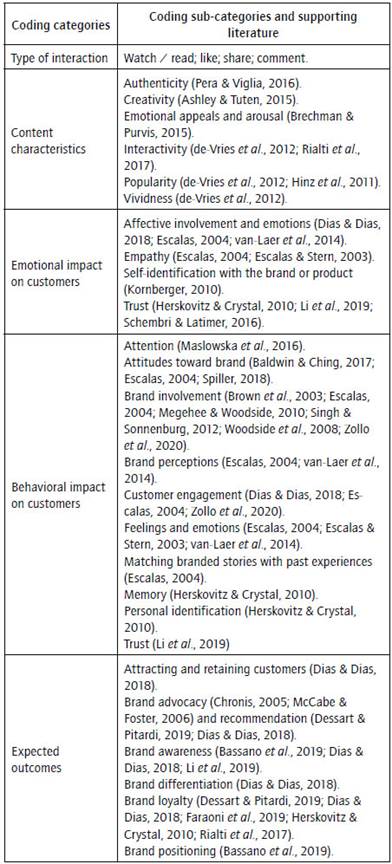

The sessions lasted an average of 1 hour and 8 minutes. Ethical procedures generally applicable to research in social sciences were adopted, including voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymous participation, and confidentiality. Prior authorization of participants, the sessions were audio recorded in order to enable transcription for data analysis. These recordings were immediately destroyed after being transcribed. Transcripts had a total of 31,985 words and were subject to theory-driven content analysis. The list of first order and second order codes is presented in table 2.

According to Bardin (2009), content analysis comprises three phases: (i) pre-analysis, focusing on an initial systematization that assists successive analysis operations, (ii) coding and data processing, and (iii) inference and interpretation, in which results are completed that condense and highlight the information obtained by the analysis.

Results

Results of the empirical study with young adults comprise two main topics: the determinants of interaction with digital storytelling campaigns and the reported impacts, considering both consumer behavior and outcomes for brands. Citations incorporated in this section offer anecdotal evidence provided by the study and should be regarded as illustrations of common points of view shared by participants across focus groups, unless otherwise stated. Information about the participants includes age, gender (M for male and F for female), participant's number, and the focus group in which they were engaged. As such, participant noted as (M1G3) would be male participant 1 of focus group 3.

Interaction with digital storytelling campaigns

Looking at how the different digital platforms enable users' interaction with brands' content and campaigns, one can generally define four categories of participation: users may watch or read the content without interaction, and they may like, share or comment if they decide to interact with it. The participants agreed that storytelling campaigns are much more captivating, and often led them to overcome their tendency to avoid interacting with brand content, as explained by one of them:

I avoid giving like to posts, because I dislike start getting notifications and be shown ads related to something you have liked. (...) But I would click on the like button for these [...]. (F3G7, 31 years)

In general, this study provides empirical support to the literature that indicates that this type of campaigns foster engagement (Dias & Dias, 2018; Escalas, 2004), confirming that digital storytelling campaigns earn more attention by consumers than commercial ones (Maslowska et al, 2016).

According to the participants, one essential factor for them to pay attention to a storytelling campaign is who posted it. In fact, it was unanimous among focus groups that both attention and any type of interaction is more dependent on who posted it than on the content characteristics, as participants stressed they only pay attention when campaigns are shared by someone they know, especially if it includes explicit recommendations:

[...] if it is a close friend who puts a description like 'Top!', 'It's worth watching!', 'It makes you think!,' or something like that, one watches it. (F1G7, 22)

Still, participants acknowledged also paying particular attention to some brands: "I think we are more attentive to certain people and brands because of the credibility that their content has and that they make us see things" (F3G8, 21). Additionally, the number of shares, likes and comments a post receives were also associated with users' attention and interaction, providing additional empirical support to extant literature (de-Vries et al, 2012; Hinz et al, 2011). Participants get curious about popular posts, and if they are surprised by the content they eventually end up contributing to the post's popularity by providing one additional share:

Sometimes I don't have a clue of what the video is about, but I'll end up watching it. I can't resist. I end up sharing. But only if I have no idea of what I will watch. Because if I can guess, I won't even open the link. (F2F4, 32)

Interestingly, participants stressed that liking is more probable on a friends' post and not directly on a brand post, in line with the findings by Hinz et al. (2011). This is expressed, for instance, by one of the participants: "I would like it but only if someone shared it. If it was the brand [posting] I wouldn't" (F3G7, 31).

The groups generally expressed that the least likely activities would be to comment and to share brand campaigns in their SNS feeds, in order to avoid discussion and keep the subject to themselves, as explained by one of the participants:

I don't comment, I don't share my opinion. If everyone starts giving opinions, people will argue. A lot may happen [.] So, what I do is watch. Of course it touches me, but I keep my opinion to myself and nothing else. (F2F2, 21)

However, they mentioned that it is common to share branded content with others by private message or in closed groups, especially if the content is interesting and useful for their peers. Citing one participant, "If I see something interesting like that, I won't share it [on my feed], I'll send it to friends via chat" (F3G5, 21).

As shown in several participants' dialogues, these results are also in line with the literature that points out helping others and social interaction (Hennig-Thurau et al, 2004) as two main motivations to share branded content with peers. So, looking at the characteristics of the storytelling campaigns, the ability to help stood out as a determinant for sharing content with others: "I usually share a lot, mostly something that raises awareness [on important topics]" (F4F4, 19); "I would share it at say 'We have to think about this. It's unbelievable'" (F2F7, 37). Popularity (de-Vries et al, 2012; Hinz et al, 2011) was also pointed out by the participants as one important characteristic that attracts their attention, as already mentioned. Yet, humor was recognized as an important determinant for tagging friends in comments as the following sentence confirm that "If it is a humorous thing, I will quickly tag someone" (M5G7, 29).

Also worth stressing that one determinant for sharing this type of content is the belief that it will have an impact on others and in solving the issue being presented in the campaign. As explained in detail, for instance, in the following transcript:

I would not share it simply because I would not make any difference [...]. This had to be shared by an enormous number of people and by celebrities and well known people that can convey the message to a lot of people. I don't think I have that ability. (M3F1, 21)

Hence, high levels of popularity, virality, and celebrity endorsement can be important to lead some consumers, like M3F1, to overcome their skepticism regarding the impacts of their interaction.

Impacts of digital storytelling campaigns

The participants generally associated the use of storytelling strategies to positive feelings, that is, the recognition and admiration for the brands that create them. In fact, storytelling campaigns led most participants to have a much more positive image for their brands, particularly valuing the fact that they talk about relevant and exciting issues, trying to contribute to a better world:

I think it's very positive that brands take advantage of their fame to launch these kind of topics and to create an impact [in society]. (F4G8, 19)

This study confirms that affective involvement and positive emotions can arise when brands launch storytelling campaigns, as suggested by extant literature (Dias & Dias, 2018; Escalas, 2004; van-Laer et al, 2014). Also, attitudes toward these brands were found to be more positive, as suggested by previous studies (Baldwin & Ching, 2017; Escalas, 2004; Spiller, 2018), and was pointed out for several participants, including the following:

I think these are good initiatives, because in addition to linking brands to this type of social concerns, it touches me [...]. It demonstrates that [brands] want to convey this image of [social responsibility]. Even if they don't have that culture, at least they have the concern to raise awareness on social issues. Which is clearly a positive point. (M5F6, 22)

Still, one interesting finding relates to content perceived authenticity (Pera & Viglia, 2016), particularly related to the association between the topic of the campaign and the brand itself. In fact, it should be noted that the participants did not always understand the choice of themes for brands' storytelling campaigns, showing higher acceptance levels when the theme addressed had some connection with the brand itself, as it was clearly the case of UNICEF. For the other brands discussed, participants frequently had doubts on the objectives of the campaign:

I still don't understand why [the brand] did that campaign. [...] I cannot see any connection between the topic and the brand. (F5F1, 25)

I cannot stop thinking that this is just an opportunity to draw attention to the brand itself. (F4F8, 19)

It's like soft marketing, still just raising attention to the brand. In my opinion, it's just "Be my customer so I can profit a lot. Believe we are good people and that we will make a difference. But just believe in it. Because we just care about money." (F2F4, 32)

They are indirectly advertising their products; they just don't want us to think that they only care about their products. (F4F4, 19)

Indeed, for several participants, the fact that more commercial brands use social themes can have an adverse effect on brand image, leading consumers to suspect that the brand is exploiting social themes for self-advantage. This fact can generate distrust among some consumers, contrary to the expected positive impact on trust suggested by several authors (Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010; Li et al., 2019; Schembri & Latimer, 2016).

Still, other participants stressed the positive impact on trust, as in the following case:

In confidence, yes. Because we are talking about values [.] because we revise ourselves or not in the values that the brands defend. And it is this type of communication, in storytelling format, that reveals these values (F3G7, 31 years old).

As suggested by Kornberger (2010), this also promotes self-identification with the brand, through the shared values.

Overall, participants in this study suggested that investing in something other than a typical commercial campaign can contribute to improving the brand image and increasing its notoriety. Storytelling campaigns were seen as more relevant than commercial campaigns, suggesting that brands should communicate their values and not only their products. Several participants pointed out that communication campaigns with a focus on values increase brand awareness and trigger curiosity, which could lead them to seek more information about the brand. Participants suggested that it can also facilitate word-of-mouth communication:

It is also a way to talk more about the brand. Because there it is, you go on commenting with others and sharing, and people will all know more about the brand. (F1G6, 24)

In view of the above, this study confirms that storytelling campaigns contribute to attract and retain customers, as suggested by Dias and Dias (2018). However, participants noted that in many cases the benefits may not be capitalized by the brand. Indeed, in some storytelling campaigns participants did not retain the brand, as they admitted being unable to identify the brand associated with some storytelling campaigns they remembered watching: "We pay more attention to the story itself, not the brand" (F2G4, 32). In such cases, the impact on the brand is absent, and consequently the campaign would be totally ineffective for branding purposes.

Regarding customer behaviors, this study indicates that the positive emotional impacts derived from storytelling campaigns could have an impact on purchase decisions, both in terms of loyalty toward such brands, as suggested by several authors (e.g., Dessart & Pitardi, 2019; Dias & Dias, 2018; Faraoni et al., 2019; Herskovitz & Crystal, 2010; Rialti et al, 2017), and as an additional selection criteria when alternatives are similar to the eyes of the consumer:

If [a brand] has a better offer, ok, I'll choose it. But if I was in doubt, for instance, two brand have the same service at the same price, then I would choose the brand with the storytelling campaigns. (F5G1, 25)

If a video touches me, I certainly won't forget it in a moment of decision. Brands make the difference. The brand makes me change. (F2G7, 37)

Moreover, some participants suggested that the impact on purchase decisions depends on the type of product and its price. It was stressed that even if these communication strategies do not result in loyalty, they create curiosity and make consumers want to know more about the brand and its products, being particularly relevant for the experimentation of unknown brands. As mentioned by one of the participants, "I may even buy it and try it. I can even like it and change [my usual brand]" (M3G2, 22).

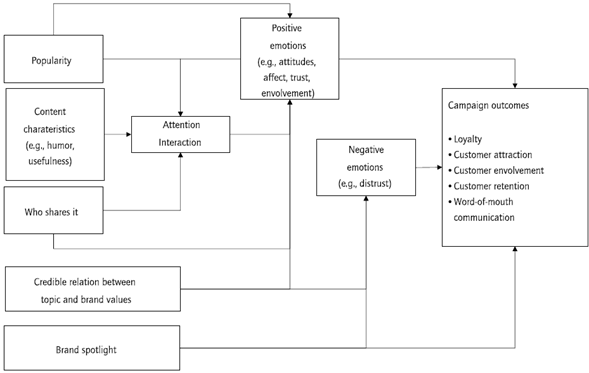

Generally, impacts on consumers' emotions toward brands were particularly evident in the discussions, confirming expected positive emotions (e.g., positive attitudes, trust), but also stressing the possibility of negative emotions (e.g., distrust) in case the audiences consider that the brand is taking advantage of a sensitive social topic. Positive emotional impacts are seen as affecting both customer acquisition and retention. Clearly, both the connection between the topic chosen for the storytelling campaign and how the brand is publicized and spotlighted during the campaign are critical factors for the campaign's branding effectiveness.

Conclusion

Storytelling campaigns emerge as a solution for strengthening relationships with customers. They aim to improve brand awareness, affect decision-making, and, ultimately, customers' choice and purchases. SNS provide the perfect platform to promote these campaigns, facilitating both its reach and interaction.

The main findings of this study are outlined in figure 1. Our results suggest that one main determinant of both attention and interaction is the person who originally shared the content. In line with the existing literature, other determinants are popularity (e.g., number of likes and comments) and content characteristics such as humor, and its usefulness for the person's network.

Although confirming that digital storytelling campaigns tend to generate positive emotions on its audience, this study points out that the lack of a credible relation between the topic (e.g., social problem) featured in the campaign and the brand itself could generate negative emotions, particularly distrust. This is one of the important contributions made by this article, which complements the indications provided so far in the literature. In general, campaign outcomes and hence its effectiveness will depend not only on the emotions generated among target audiences, but also on how the campaign draws attention to the brand.

In fact, although this study suggests that the brand should not be the spotlight in storytelling campaigns to afford interaction and strong emotional arousal, the audience often disregards and does not detect the brand creating the campaign, which would result in total lack of positive impacts on the brand, and therefore campaign ineffectiveness. As such, the balance between branded content and storytelling seems particularly challenging for practitioners. Moreover, the complexity of the determinants of consumer interaction with storytelling campaigns and, particularly, the positive and negative emotions generated, that ultimately will determine campaign's outcomes, is one important contribution of this study, and is expected to be valuable for both researchers and practitioners.

This article contributes with valuable clues that could boost the effectiveness of digital storytelling campaigns targeted at young consumers. As a decisive success factor, brands can focus either on expected impacts in long-term customer relationship management and loyalty levels or on short-term customer acquisition by arousing curiosity for a new product or different service. Clearly, digital storytelling campaigns seem powerful tools for branding, as well as a valid alternative for traditional advertising strategies.

A final note regarding research limitations and suggestions for future research. One main limitation of this study refers to the sampling method and dimension. The sample used is non-probabilistic and limited in size. Despite being adequate for the purpose of this study, and enabling data saturation, our sample does not allow the generalization of results. Therefore, we recommend replicating and continuing this study in future research initiatives aimed at validating the results presented. The study was conducted with Portuguese consumers, members of a particular cultural context that should also be considered when interpreting the results. For this reason, future research studies should consider consumers from other regions and cultural backgrounds. Cross-cultural comparisons could also be considered. In addition, other age groups could be taken into consideration in future research initiatives, including comparisons between individuals of various generations.

As evidenced throughout these pages, this is a particularly relevant topic for marketing communication, with very interesting potential impacts on customer behavior and relationships with brands, thus deserving increased attention by academics. Future research may consider other methodological approaches, namely quantitative, which could provide additional insights to better understand the effectiveness and impacts of digital storytelling campaigns. Some suggestions for future research include comparing campaigns from well-known and new brands or analyzing digital storytelling campaigns from the point of view of the semiotics of communication and neuromarketing, namely by exploring how the campaigns' characteristics can influence the consumer behavior.