Introduction

The demand for food delivery services in Mexico has increased in the last decade, particularly for fast food franchises, constituting a significant change in the food industry and turning this service modality into an opportunity to innovate the way businesses in the sector offer their products. This growth was boosted at the beginning of 2020 for franchises and independent establishments in Mexico. As in several countries, the sanitary emergency caused by the spread of COVID-19 led to the imposition of lockdown measures, resulting in severe restrictions on mobility and access to public places, such as restaurants and food establishments, thus forcing franchises to significantly increase the offer of delivery services and independent restaurants to venture into this service modality to continue operating.

This food delivery service ecosystem has specific relevance in countries such as Mexico due to what it represents for its economy. The food sector has maintained stable participation in the gross domestic product (CDP) range by generating approximately 247.4 billion Mexican pesos, representing 1.1% of the country's total CDP in the last decade. According to data provided by the 2019 Economic Censuses in Mexico, home delivery services account for 15.2% of the activities performed by companies (INEGI, 2019).

Additionally, Mexican consumers' habits changed due to the pandemic. Food service delivery sites experienced a stable and growing behavior caused by the second wave of infections in April, with 5% of online purchases rising to 11°% by October 2020 as Internet users adopted these services for frequent use (Mexican Association of Online Sales [AMVO], 2020). This change derived from the lockdown imposed as a public health measure hastened opening opportunities for food businesses to venture into food delivery services (De la Cruz & May, 2021; INECI, 2019). Nevertheless, organizations should know how to drive co-creation behavior among their consumers to improve the quality of the service and create value together.

As a result, food establishments had to offer a new service, bringing challenges in terms of understanding new customer's consumption habits. They also had to discover this modality, previously unknown or little explored by many. This situation attracted the attention of restaurateurs, entrepreneurs in the food sector, and marketing academics, who seek to understand the customers' role and the implications of their participation during the food delivery service experience. In this context, innovative and applicable marketing theories and approaches help respond to the current challenges of consumer behavior and the changing habits brought about by confinement. These marketing theories include the Service-Dominant logic (SD-logic) and the Service Ecosystem theory (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, 2008a, 2016).

The core concept of SD-logic is that the customer is always a co-creator of value (Vargo & Lusch, 2004), whereby value co-creation occurs between active participants and collaborative partners in relational exchanges. Furthermore, customers co-create value with the establishment by participating in the entire service value process (Tommasetti et al., 2017; Yi & Gong, 2013). Applying these innovative marketing theories lays the groundwork for possible responses and options for the food delivery service establishment ecosystem value and the customer behavior required to co-create value.

While several authors have highlighted the importance of understanding and managing traditional customer behavior towards co-creative behavior, the research that identifies the customer co-creation behavior in emerging environments and services is limited (Delpechitre et al., 2018; Tommasetti et al., 2017). For example, Yi and Gong (2013) developed a CVCB scale that integrates both active and citizen customer behavior, proposing that such a scale be implemented to evaluate and reward customer performance since, if a company regularly evaluates and rewards activities, customers will be more willing to engage in value co-creation activities.

However, although value co-creation is often considered an important process that companies use to maintain a competitive advantage in various service ecosystems, the literature contains little information on the role of customers during the value exchange in providing food delivery services. Most research on CVCB has focused on determining the relationship of its variables (customer engagement and citizenship behavior) with those of employee behavior (performance, satisfaction, and commitment) and identifying key drivers of employee behavior towards customers (Delpechitre et al., 2018; Yi et al., 2011).

The literature contains several empirical investigations regarding CVCB in areas such as the provision of educational services (Encinas & Cavazos, 2016; Foroudi et al., 2018; Moreno & Calderón, 2017), lodging services (Farrukh & Ansari, 2021; Liu & Jo, 2020; Solakis et al., 2022), among customers of personal care companies (Cossío-Silva et al., 2016; Vega-Vazquez et al., 2013), in the provision of public services (Ida, 2017; Luu et al., 2018), in supermarkets (Shamim et al., 2016), the communications sector (Delpechitre et al., 2018), and hospitals (Samsa & Yüce, 2022). Hitherto, there is no empirical evidence that positively and significantly relates CPB and CCB to CVCB within the emerging and little-known food delivery services industry in Mexico during the COVID-19, considering its social, cultural, and technological particularities as a developing country. Therefore, this research aims to verify if CPB and CCB are related to the generation of CVCB in the Mexican food delivery services ecosystem.

This study has the following structure: starting with a literature review of the inclusion of food delivery services in theories such as the SD-logic and service ecosystems theory, continuing with the approach to customer co-creation behavior, including participatory behavior and citizenship. Then, we present the methodology and results of the quantitative approach work to give way to the discussions and conclusions of the research.

Literature review

Involving food service delivery into SD-logic and service ecosystem approach

Due to the changes in consumer habits resulting from the mobility restrictions caused by the pandemic, independent food businesses, primarily local, had to move into food delivery services, just like franchises do (Goddard, 2020; Hobbs, 2020). In response to these global challenges, both food business sector experts and service academics seek to develop and identify best practices that will enable them to sustain the organizations over time. In this context, innovative and applicable marketing theories such as SD-logic and service ecosystem approach increasingly emphasize that value arises from the reciprocal interaction between customers and suppliers and not only from the use of the good or service (Grönroos, 2008; Vargo & Lusch, 2004).

The SD-logic theory has its background in the 80s when service marketing was born as an underestimated discipline. However, nowadays, it is no longer only considered a branch of marketing but has become a perspective widely applied in various disciplines (Vargo & Lusch, 2017) because it considers integrally and innovatively all the actors and resources that are part of the service. At the same time, it allows including the particularities of each and their cultural, social and circumstantial particularities. Therefore, the SD-logic is consolidated in the marketing discipline as one of the main answers to the current complex scenario, considering that the service is fundamental for the economic exchange and the generation of value without focusing on the product as it has traditionally been done, but also not replacing its essential role within the exchange (Vargo & Akaka, 2009).

One of the main foundations of the SD-logic is that the exchange is based on service and is produced through a dynamic co-creation process (mutual benefits jointly achieved) that involves all actors and resources, identifying two types of resources: operative (behaviors, skills, and attitudes) and operant resources, on which an action is exerted to achieve the benefit (platforms, facilities, processes) (Kotler et al, 2021; Vargo & Lusch, 2004), and which emphasize that value co-creation is achieved through the efficient integration of resources and actors in the global environment between organizations and customers. Therefore, the co-production of multiple actors generates value during the service, leaving behind the traditional conceptualization of the division between service and product determined by its tangibility and intangibility, evolving to an approach that argues that the service can be provided directly or indirectly, through a good, as an intangible product (Grönroos, 2011).

Coupled and very closely with the above, SD-logic integrates the service ecosystems approach, a concept taken from biology to understand better the interactions between actors (living components) and factors (non-living components) as members of a whole, generated by their interaction and cooperation, a co-created value (Lusch & Vargo, 2014). These ecosystems have been defined by Lusch and Vargo (2014, p. 24) as a "relatively autonomous and self-adjusting system of agents that integrate resources and are connected by shared organizational arrangements and mutual value creation through the exchange of services." Food delivery services are framed within this definition since the commercial activity integrates both the connections and links between food establishments and customers but also the flow and exchange that takes place before, during, and after the interaction (Grõnroos, 2011; Lusch & Vargo, 2014; Meynhardt et al,, 2016).

The service ecosystem perspective is firmly rooted in the general theory of service-based exchange, which focuses on organizations' strategies and actions to attract and retain customers. Regarding food delivery services, primarily developed currently in digital environments, the technology turns out to be the resource that allows impersonal and remote interaction between the company and its customers, being the means of interaction, even an interaction in which the customer does with just technological platforms (Goddard, 2020; Siaw & Okorie, 2022; Vargo et al,, 2015). This approach integrates SD-logic premises, pointing out that innovation is an emergent property of the ecosystem, and technology is a resource on which this innovation is supported (Akaka et al, 2019; Chi et al, 2020).

To innovate the management of food delivery services, businesses must move in line with the literature advances, from basing the exchange of value on goods, in which the seller offers value through a good, to an approach focused on the service as the primary means to co-create value, considering that the exchange in the market is the process in which the actors integrate their knowledge for mutual benefit (Lusch & Vargo, 2006; Vargo & Lusch, 2008a, 2017; Vargo et al, 2020). Hence, food delivery services are very dynamic, and their functioning is based on the participation of all its actors, including the customer, under the business' policies and arrangements (Chai & Yat, 2019). In this sense, the entire process of food delivery services can be understood from the participation of its actors and their interactions through a synergy that co-creates the expected value.

Food delivery services value co-creation

Market management continues to evolve towards a service-based exchange logic, advocating a systemic understanding of value co-creation and the influence of the context in which the value of use is developed. Consequently, value co-creation is currently understood as a marketing and management strategy that focuses on engaging the customer to generate value in an innovative way (Perks et al, 2012), changing the traditional view of the producer-customer relationship, which privileges customer expectation for a value based on tangibility and classic exchange.

The food delivery services ecosystem poses a challenge more significant than this classic approach, as it is developed remotely through the organization's capabilities and competencies and the customer's knowledge and skills through impersonal or digital communication. In addition to the above, value co-creation requires organizations not to assume that they know customers' needs in an ideal way and therefore "offer value," but to co-create this value since it is the customer who knows their needs and how to satisfy them. Organizations consequently not only need to know consumption factors, but to involve the customer with greater participation and interaction during production, marketing, and value in use, achieving a more comprehensive result, which is not limited to generating a value offer but obtaining it jointly (Dollinger et al, 2018; Vargo et al., 2008a).

Vargo et al. (2017) conceptualize value from the perspective of the service ecosystem, considering specific characteristics. First, they mention that value is phenomenological, which implies that what is valuable for one actor in one place and time may not be so for another actor or that same actor at another time and place. Furthermore, the authors emphasize that value is multidimensional as it is co-created through multiple coordination between actors and institutional arrangements so that elements such as social context and culture determine the concept of the value and its co-creation in each market. Finally, the authors mention that value is emergent as all actors must exchange resources within an ecosystem, causing the self-organization of the ecosystem through the interactions between its multiple actors and the various institutional arrangements.

Considering that value is not a benefit that can be transmitted from the establishment to the customer but is achieved jointly among all the actors that are part of the exchange (Edvardsson et al, 2011), three of the 6 SD-logic axioms (Axiom 2/FP6, Axiom 4/FP10, and Axiom 5/FP11) strongly emphasize the joint generation of value, stressing that value is always co-created with the customer's participation, who phenomenologically determines real value through the coordination and organizational arrangements of the business. Applying these axioms in the food delivery services process allows considering the specific characteristics of both the resources -operating and operational- as well as the actors and their interaction during the service delivery, as considered below.

Axiom 2/FP6 value is co-created by multiple actors, including the beneficiary. The expected value within the home service is not transferable that the business can deliver to the customer but can only be achieved jointly by the service ecosystem actors. Because value is always co-created, its achievement cannot be solely attributed to the establishment since its role as a co-creating actor consists mainly in making a value proposition. No actor can deliver value to the rest of the ecosystem alone, but they can contribute through their skills, capabilities, and resources to obtain the intended benefits (Vargo & Lusch, 2016).

Axiom 4/FP10 value is always uniquely and phenomeno-logically determined by the beneficiary. The food delivery services ecosystem faces more marketing and management challenges than the rest of the delivery services, which focus on the enhanced service by speed and efficiency with which customers receive their orders. However, this service efficiency, from the SD-logic perspective, is the result of joint participation between the business and the customer, being the customer who determines it phenom-enologically, which means it will depend on each customer, as their characteristics, skills, resources, and environment, in general, determine their acceptable role as value co-creator, in addition to the fact that for each customer the value will be different from their perspective, experience, and context (Ncube & Nesamvuni, 2019).

Axiom 5/FP11 value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements. This value is multidimensional, which means that its achievement, in addition to the active participation of all actors, requires the synergy generated by the establishment's corporate management policies and strategies. However, even with the standardization of service policies, the social context and the local culture will determine the concept of value in each market segment. Therefore, and given that the customer will determine what valuable based on their perspective, which will be influenced by their specific context and may change over time is, it is relevant to identify and understand the CVCB in the food delivery services ecosystem since it is through their participation and the establishment's offer that value can be co-created or co-destructed.

Customer value co-creation behavior

With the paradigm shift from the product exchange to the service exchange (Lusch & Vargo, 2008a), the role of customers has also changed from passive customers waiting for benefits to co-creators of value, who, together with the establishment, achieve those benefits. In the quest to delimit what is expected from the customer as a co-creator, approaches such as CVCB are integrated, as it involves a commitment during the service process since the process will not be successful without the customer's participation, involvement, and commitment to collaborate with the seller as well as is related to purchase intention (Bu et al, 2022; Delpechitre et al, 2018; Luk et al, 2018; Yi et al., 2011). Another integrated approach is consumer citizenship behavior, which is voluntary and provides extraordinary value to the firm but is not forcibly for value co-creation (Yi & Gong, 2013).

In this way, Yi and Gong (2013) define CVCB as the joint creation of value by the company and the customer. This term is used to describe the actual participation of the customer in the value creation process (Delpechitre et al, 2018). Yi and Gong (2013) explore the hierarchical dimensionality of CVCB with the validation of a scale that identifies and measures customer co-creation behavior. The scale considers CPB, which refers to the required behavior necessary for successful value co-creation, and CCB, voluntary behavior that provides extraordinary value to the firm for value co-creation. The co-creation process requires collaborative activities of employees and customers to successfully create value (Yi et al, 2011), which demands that all its actors are willing and ready to share complementary experience, skills, and knowledge to develop win-win situations for all participants (Delpechitre et al, 2018).

Customer citizenship behavior

Within the context of value co-creation, organizations seek to understand the current customer role during the exchange, so they start by studying and understanding their behavior before, during, and after service provision (Jung & Yoo, 2017). In service marketing, different approaches to consumer behavior have emerged, such as Customer Voluntary Performance (Bettencourt, 1997) and Customer Helping Behavior (Johnson, 2010), both considering the customer as a human resource of the organization or even as a partial employee. Specifically, Bettencourt (1997) identifies three dimensions that constitute this helping behavior: loyalty, cooperation, and participation, stressing that customers that tend to become advisors and promoters of the brand for other customers provide valuable support to improve customer service.

The CCB emerges as part of this approach that seeks a positive voluntary behavior of the consumer towards the company. CCB is defined as "voluntary and discretionary behaviors that are not necessary for the success of the production and/or provision of the service but that, as a whole, help the service organization in general" (Groth, 2005, p. 11). In addition, the author points out that due to CCB being the result of repeated satisfactory service experiences, the customer tends to generate business loyalty, thus making it easier for them to show greater willingness to provide feedback and recommend the service to others.

In addition to the above, Yi and Gong (2008) argue that CCB is integrated by the dimensions of feedback, advocacy, help, and tolerance, stating that customers may become service citizens if they consider that the value exchange has been fair. Presenting a CCB scale based on this perceived fair value, the authors stress that both the distributive, procedural and interpersonal justice perceived by customers leads to a more significant positive effect, which is directly related to the level of consumer citizenship towards the organization. Finally, adding to the conceptualization, measurement and understanding of CCB, Bartikowski and Walsh (2011) relate "Customer-based Corporate Reputation" (CBR) with CCB, analyzing the implications of commitment and loyalty as variables that mediate the existing CBR-CCB relationship. As a result, while CCB has a more significant relationship with helping other customers, CBR directly impacts the organization's commercial and positioning objectives.

Another element that has been associated with the CCB is the affective commitment that the customer develops towards the business, identifying a positive relationship between the CCB and this element, stressing that the level of customer commitment as a citizen of the brand will be a function of the service provided and the satisfaction of the value in use (Curth et al, 2014). Regarding measuring CCB within specific service contexts, Bove et al. (2003) use a scale of 8 dimensions to empirically prove that CCB is not necessarily part of customer engagement during the service provided. However, it does generate greater efficiency, identifying that the business's commitment towards its users is the most important predictor for CCB to be generated.

Another example of application in specific environments is the study developed by Encinas and Cavazos (2016). Based on the scale developed by Bove et al. (2003), Encinas and Cavazos measured CCB in the higher education service, stressing that benevolent acts are the variable that most influences the generation of CCB, while affiliation relationships are the variable that contributes the least in this service ecosystem.

In the food business sector, Kim and Tang (2020) recently related CCB with creating perceived value in restaurants. The authors show that CCB has a more significant impact on customers' perceived value than participation behavior, another approach to customer behavior that has recently become more relevant due to the increasing participation of customers in service ecosystems. As part of this research, theoretical content on CPB is presented, being a construct that constitutes cvcp. This line of discussion leads to the following hypothesis:

H1. CPB is positively and significantly related to CVCB in the Mexican food delivery service ecosystem.

Customer participation behavior

Considering that value exchange is based on the interaction of the actors involved in the service, several studies identify CPB as the basis of co-creation and the permanence of customers in the long term (Luk et al, 2018; Revilla-Camacho et al, 2015; Yi et al, 2011) as it recognizes the essential role of the customer during the value exchange, making them an active co-producer of value. This approach is paired with co-creation premises (Lusch & Vargo, 2008b), and its adoption has been the basis for several types of research that seek to identify how customers participate in the service delivery process and achieve the expected benefits.

For instance, Delpechitre et al. (2018) stress that CPB includes the physical, virtual, and mental processes that integrate the service experience, identifying that customer participation is naturally multidimensional. This means it is integrated by different dimensions (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, psychological, resource, relational and global processes). In addition to the foregoing, organizations are aware that the effectiveness of their value proposition is in measure of the joint participation for the achievement of the benefits expected by the organization, such as customer loyalty, a business objective that CPB helps achieve since when a customer is active, the customer-establishment relationship is consolidated, decreasing the risk that the customer eventually leaves (Revilla-Camacho et al, 2015).

However, dynamic behavior not only adds to customer loyalty but is also directly related to employee behavior and service innovation, especially during the interaction through digital and/or remote media, since when the customer is active, an interpersonal mediation between the customer and the employee is strengthened (Li & Hsu, 2018). Therefore, given that the exchange's success depends largely on the customer's commitment to co-create, companies consider their customers the leading actor in the service operation. As a result, they look for their customers to have the expected and required behaviors necessary for the successful production and delivery of the service, since, unlike citizen behavior, CPB is required for the successful production and delivery of the service (Yi et al, 2011). Following the arguments mentioned above, the following hypothesis can be made:

H2. CCB is positively and significantly related to CVCB in the Mexican food delivery service ecosystem.

Methodology

This is a quantitative, cross-sectional, and explanatory research (Hernández et al., 2010). Fieldwork was conducted using the survey technique through non-probabilistic convenience sampling, carried out for four months, starting in August 2021, with a total sample of 434 valid surveys. The questionnaire adopted was proposed by Yi and Gong (2013) and consists of 29 items on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always; it also contains a section that helps to know the informant's profile. The study population was individuals over 18 years who reported having made at least one purchase of food and/or beverages through the home delivery service modality. The informant profile was as follows: 66% were women, 83% of individuals were between 18 and 32 years, and 37% said they requested their service by telephone (table 1).

Table 1 Informant profile and communication means with the company.

| Variable | Category | Share |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 66% |

| Male | 34% | |

| Age | 18 to 32 years | 83% |

| 33 to 47 years | 12% | |

| Over 48 years | 5% | |

| Means of communication | Phone call | 37% |

| Social media | 21% | |

| Mobile application | 36% | |

| Website | 6% | |

| Type of restaurant | Franchise | 67% |

| Independent | 33% |

Source: authors, based on Stata Software results.

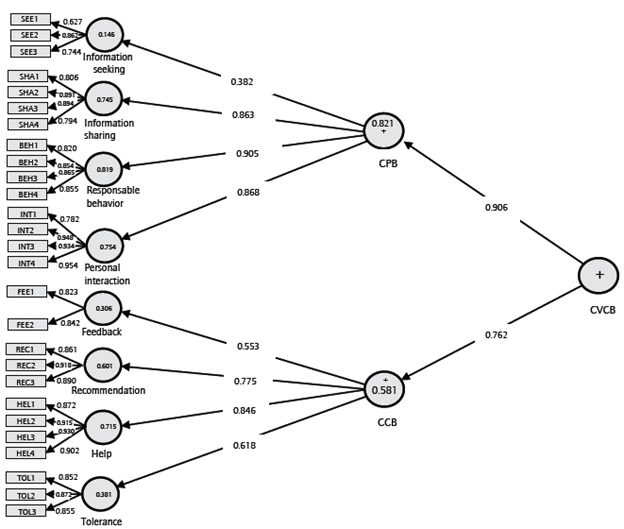

Structural equation modeling -based on partial least squares (PLS) using third-order hierarchical component modeling- was used to validate the model proposed by Yi and Gong (2013). In that model, the manifest variables determine the eight first-order constructs, i.e., information seeking, information sharing, responsible behavior and personal interaction, feedback, recommendation, help, and tolerance. Subsequently, these variables shape the second-order constructs. i.e., participatory behavior and citizenship behavior, and finally, these last ones shape the third-order construct, i.e., value creation, as methodologically determined by the literature consulted (Hair et al., 2021; Wetzels et al., 2009).

Following Hair et al. (2021), the measurement model was evaluated through composite reliability (CR) to verify the internal consistency of the constructs. As shown in table 2, the indicators obtained show a value higher than 0.7, which covers the reliability requirement. Additionally, it is observed that the constructs experienced a level greater than 0.5 concerning the average variance extracted (AVE), which fulfills the characteristic of convergent validity.

Table 2 Reliability and validity indicators of the first-order model construct.

| First order construct | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|

| Information seeking | 0.79 | 0.56 |

| Information sharing | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| Responsible behavior | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| Personal interaction | 0.94 | 0.82 |

| Feedback | 0.82 | 0.69 |

| Recommendation | 0.92 | 0.79 |

| Help | 0.94 | 0.82 |

| Tolerance | 0.90 | 0.74 |

Source: authors, based on results obtained from Smart PLS Software.

Additionally, the discriminant validity of the first-order constructs was verified employing the Fornell and Larcker test (1981), observing that the square root of the AVE is greater than the correlations between constructs (table 3). Table 4 shows the CR and AVE levels of the second and third-order constructs, which are higher than the levels recommended by the literature (Hair et al., 2021). Thus, higher-order constructs provide evidence of reliability.

Table 3 Fornell-Lacker test.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Help | 00.905 | |||||||

| 2. Information seeking | 0.256 | 0.751 | ||||||

| 3. Information sharing | 0.158 | 0.303 | 0.847 | |||||

| 4. Responsible behavior | 0.179 | 0.281 | 0.709 | 0.849 | ||||

| 5. Personal interaction | 0.230 | 0.198 | 0.599 | 0.699 | 0.907 | |||

| 6. Recommendation | 0.435 | 0.320 | 0.362 | 0.384 | 0.377 | 0.890 | ||

| 7. Feedback | 0.364 | 0.247 | 0.201 | 0.177 | 0.162 | 0.427 | 0.832 | |

| 8. Tolerance | 0.367 | 0.14 | 0.255 | 0.252 | 0.300 | 0.334 | 0.116 | 0.860 |

Source: Smart PLS Software.

Results and discussion

Structural equation modeling, based on partial least squares (PLS) using third-order hierarchical component modeling, was used to validate the model proposed by Yi and Gong (2013). In that model, the manifest variables determine the eight first-order constructs, i.e., information seeking, information sharing, responsible behavior, personal interaction, feedback, recommendation, help and tolerance; second-order constructs, i.e., CPB and customer citizen behavior (CCB); and the third-order construct, i.e., value co-creation behavior (CVCB).

The model proposed by Yi and Gong (2013) and implemented in the Mexican context was validated using structural equation modeling. First, the reflexive model based on hierarchical and third-order components was verified (Hair et al, 2021). Then, after performing the bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples, the factor loadings of first-order constructs were evaluated and, following Hair et al. (2010), items with factor loadings above 0.5 were kept in the model. Consequently, two items, INT5 and FEE2, were discarded. Subsequently, all factor loadings experienced higher values than 0.60 and were statistically significant (P < 0.001). This confirms that the scale proposed by Yi and Gond (2013) is reliable for measuring value co-creation behavior in the food service delivery ecosystem.

The overall model fit (GoF) was verified using the indicator suggested by Tenenhaus et al. (2005), which establishes a GoF level between 0 and 1, determined using the geometric mean of the AVE (Wetzels et al., 2009) and the average of the R2, as follows: GoF = √((AVEP)- (Rˆ2)-). In addition, the literature proposes the following thresholds to determine a model's level of fit: GoFsmall = 0.1, GoFmedium = 0.25, GoFlarge = 0.36 (Wetzels et al, 2009). Thus, the model under study yields a GoF of 0.64, representing a significant fit, so its results can be generalized.

The results show that the four dimensions that explain the CPB (information seeking, information sharing, responsible behavior, and personal interaction) show factor loadings greater than 0.8, except for information seeking (β = 0.39), all being statistically significant (P < 0.001). The same occurs with the four dimensions (feedback, recommendation, help, and tolerance) that determine CCB, with loadings greater than 0.5 and statistical significance. These results demonstrate that the eight first-order dimensions help explain the second-order constructs, CPB and CCB, respectively, as shown in figure 1.

After meeting the assumptions of the measurement model, we performed a structural model to test the hypothesis. The structural equation model's path coefficients were used to evaluate the hypotheses. CPB influences positively and is statistically significant for CVCB (β = 0.906; P < 0.001), whereby H1 is strongly supported (table 5). The results are consistent with other research conducted in different service ecosystems, such as in hospitality (Bouchriha et al., 2021; Liu & Jo, 2020), health care services (Hau et al., 2017; Samsa & Yüce, 2022), and retail services (Shamim & Ghazali, 2014; Tran & Vu, 2021), stressing that CPB as in-role behavior performance is strongly present during the service exchange, denoting those activities such as information sharing, responsible behavior, and interaction occur significantly in the Mexican food delivery service ecosystem.

Additionally, it is observed that the CCB has a positive and significant influence (P < 0.001) on CVCB, in this case, with a path coefficient of 0.762, thus supporting H2 (table 5). This result is in line with what Yi and Gong (2013) reported. They consider that CCB is voluntary behavior. Therefore, although significant, it is not strictly necessary for the value co-creation process. In the same sense, these results are related to what was exposed in previous research (Ida, 2017), where the author concludes that help, feedback, tolerance, and recommendation are positively and significantly related to citizen behavior in turn with the CVCB.

Table 5 Hypothesis results.

| Hypothesis | Path | Path coefficient | T statistics | P values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CPB-> CVCB | 0.906 | 52.6 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | CCB -> CVCB | 0.762 | 29.15 | 0.000 | Supported |

Source: authors, based on results obtained from Smart PLS Software.

Along the same lines, the results obtained support the findings reported by Shamim et al. (2016) in the research carried out among supermarket customers in Malaysia, who found that both the CPB and the CCB determine the CVCB, being the first the one that is more closely related with the co-creation of value. This shows that CCB as extra-role behavior during the service interaction is less likely to be present than the required behavior during the service exchange, denoting those activities such as seeking information about the service and giving feedback, occurs less frequently in the food service delivery ecosystem (table 5).

In accordance with the findings obtained by previous service ecosystem research (Delpechitre et al, 2018; Luk et al, 2018; Revilla-Camacho et al, 2015; Yi et al, 2011), this research also notes that the CPB component has a more significant impact on CVCB than CCB, denoting the relevance of consumer participation to be an active co-producer of value, an approach paired with the value co-creation premises (Lusch & Vargo, 2008b).

Considering the study results, it is possible to offer some suggestions to restaurant owners and managers that participate in a consolidated way or begin to explore the Mexican food delivery service. First, CVCB is crucial to the success of restaurants within the growing food delivery service ecosystem due to co-creation behavior being driven in line with CPB and CCB. Second, sharing customer's information with front-line employees is essential, so it is suggested that the organization develops strategies for the customer to explain in detail and provide the employee with all the necessary information about their order. Third, it is valuable for the restaurant to encourage responsible customer behavior through actions that help customers to comply with business policies and the employee instructions, as well as to consider specific actions to generate a personal interaction based on friendly and polite between the establishment's employees. Finally, it is recommended that managers promote the participation of customers in virtual platforms, in which they express their experience of having requested food service delivery, recommend the company's services, and where the most experienced can guide new customers about the best way to order food to obtain a better experience.

Conclusions

This research aimed to verify if CPB and CCB are related to the generation of CVCB in the Mexican food delivery service ecosystem. For this reason, a questionnaire adapted for customers of this economic activity was provided, totaling 434 valid surveys. In addition, the structural equation modeling technique was followed, i.e., third-order hierarchical component modeling, employing the partial least squares (PLS) method, using the Smart PLS v3 software.

Our findings show that the measurement model meets the reliability and construct validity requirements. In contrast, convergent and discriminant validity was verified through the AVE levels and the Fornell and Larcker test, respectively. Additionally, the model's overall fit was met by exceeding the threshold established by Wetzels et al. (2009) so that the model results are amenable to analysis. In the structural model, the results manifest that the factor loadings of the eight first-order latent variables exceed 0.5, except for the information seeking construct (β= 0.38). Similarly, the loadings of the second-order constructs on the third-order variable are greater than 0.7, all these loadings being statistically significant (P < 0.001). It is concluded that CPB has the most significant influence (β = 0.91) on value co-creation between consumers and food service provider companies, thus supporting both hypotheses. This CPB includes the variables that the literature considers necessary actions by customers to co-create value during the consumption experience, information search, information exchange, responsible behavior, and personal interaction, thus empirically verifying the importance of these activities by the customer at the time of purchase and the interaction with the establishment as well as with other customers.

Our results could help restaurants managers identify the importance of sharing customer information with front-line employees, making it easier for establishments to develop strategies for the customer to explain their order in detail, sharing all necessary information with the employee.

In addition, managers can promote customer participation in virtual platforms to share their food service delivery experience, generating strategies for customers to recommend the restaurant, and where the most experienced can guide new customers on the best way to order food delivery.

Among the limitations of this research, it should be noted that it was based on a non-probabilistic sampling, called convenience sampling. In addition, more than 80% of informants were young people between 18 and 32 years in a particular region of the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. Hence, future research should focus on analyzing customer behavior, not only in other regions of Mexico but also among customers of other generations and compare whether there are considerable differences in customer behavior between them for value co-creation.