Introduction

The rapid and abrupt behavioral changes that occurred during the international health contingency due to COVID-19 meant different challenges for higher education (HE), since all face-to-face classes and activities migrated to an emerging methodology of online or hybrid education (Dubey & Pandey, 2020). Both methods have represented not only an academic challenge for all the actors involved -including students, teachers, and HE managers- but also market challenges for the universities due to the competition among HEIS to attract and retain as many students as possible (Musselin, 2018). As a result, the implementation of generic marketing strategies to achieve market participation objectives has grown significantly, opting for favoring student satisfaction over academic priorities (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, 2012).

Some of the actions deployed by HEIS to maintain and increase their enrollment is to attend and manage student complaint behavior (SCB), favoring students' immediate satisfaction and, with it, their permanence, just like tourism or entertainment companies do. However, the nature of the HE service is far from resembling these industries. Therefore, understanding and managing SCB continues to attract the attention of scholars, marketing experts, and HEIS managers due to its relevance and the crossroads being faced in achieving student satisfaction in a context of global changes that demands ensuring HE sustainability.

In an attempt to enhance the understanding of the service experience, the literature has generated studies on customer complaint behavior (CCB) mainly focused on deterministic intentions and customer service evaluations (e.g., Blodgett et al., 1997; Singh & Pandya, 1991; Tax et al., 1998; Zeithaml et al, 1996) as a complaint style (Hart & Coates, 2010; Su & Bao, 2001). Specifically addressing SCB within SDL, Tronvoll (2008, p. 610) presented a dynamic complaint behavior model resembling SCB alongside CCB.

Nevertheless, various authors agree that HE service cannot be standardized and, consequently, its management must be different. Few studies have focused on visualizing the student differently from a customer and thus manage their complaint behavior accordingly (Bunce et al., 2017; Díaz-Méndez et al, 2019; Senior et al., 2017). So far, no research focused on SCB has been addressed in a specific environment such as the Latin America region, also considering the HE service complex ecosystem in terms of value co-creation, especially during the rapid and forced migration from face-to-face to virtual and hybrid education modalities (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, 2012; Gupta, 2018). In this context, the following question arises: Why should SCB be managed differently from CCB?

To ensure HE service sustainability, especially when the ecosystem faces global challenges, new theories, approaches, and perspectives on services have emerged; that is the case of Service Science (IfM & IBM, 2008; Spohrer & Maglio, 2008), many-to-many marketing (Gummesson, 2006, 2014), the Viable Systems Approach (Barile et al, 2012), or the Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) proposed by Vargo and Lusch (2004, 2008, 2016, 2017). These approaches are suitable to improve SCB management since they make possible to consider both the service ecosystem complexity and the student value co-creation behavior (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, 2012; Vargo & Lusch, 2008, 2016, 2017).

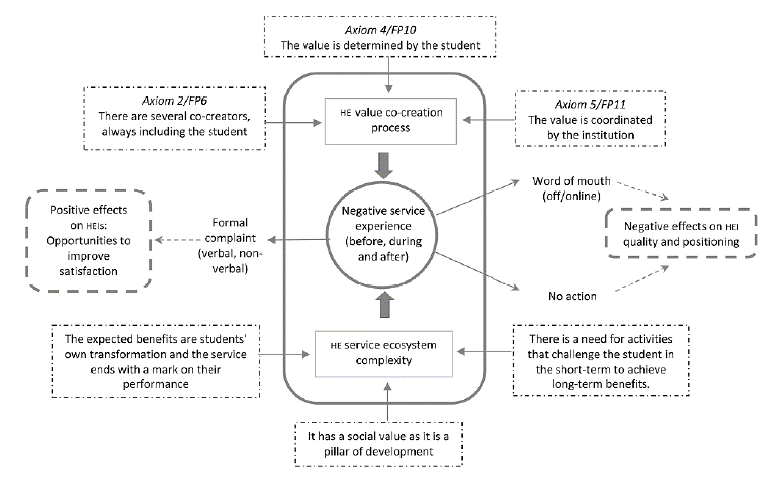

Using the SDL lexicon, specifically the premise of value co-creation, which is explained by three of its axioms -axiom 2/FP6 (value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary), axiom 4/FP10 (value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary, and axiom 5/fp11 (value co-creation is coordinated through institutions and institutional arrangements generated by the actors)-, it is possible to understand that the achievement of the benefits sought within a university depends on the efficient integration of the institutional arrangements, infrastructure and technology implemented by the university (operational resources) with the student's prior knowledge and personal skills (operant resources). Therefore, it is possible to consider a co-responsibility for the satisfaction, dissatisfaction or non-satisfaction of the actors involved.

This reflection paper aims to integrate into the SCB framework a different perspective of the value co-creation process, considering the complexity of the HE service ecosystem. Through a critical analysis of the implications of applying the customer/student analogy in complaint management, this works seeks to facilitate HEIS to ensure students' satisfaction and, at the same time, safeguard the HE social value managing student complaint behavior. This reflection makes it possible to strengthen the HE framework in the context of recent service developments, a contribution hitherto unavailable in the literature.

This paper is structured as follows. First, the literature review protocol is presented. Secondly, the student-customer analogy debate and the most relevant CCB and SCB models are exposed. Then, the HE service complexity is analyzed to better understand the differences between HE and other service ecosystems, emphasizing the expected long-term value through students' personal and professional transformation. Next, and along with the Service Ecosystem theory, the three SDL axioms that explain the value co-creation premise are highlighted, involving participating actors' implicit responsibility in the service experience and the expected outcomes. Finally, a conceptual framework for the SCB proposal is presented, considering the main repercussions over current HE management, which requires facing market challenges without putting HE sustainability at risk.

Literature review

An in-depth review of the most representative previous research works on the subject problem of this research is presented for the period 1994-2021. Using databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, Emerald Insight, EBSCO Information Services, and Google Scholar, a number of scientific articles were obtained from public access platforms and licenses granted by HEIS. The literature search and review revolved around the research keywords CCB, SDL, service ecosystem complexity, SCB, and value co-creation. The works addressed are of scientific and academic nature, published in English, and indexed in journals focused on HE service from the perspective of marketing and pedagogy, as well as on the analysis and management of customer behavior. Bibliographic material published in non-indexed journals and whose disciplinary content had no clear relationship with the objective of this study were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 35 publications.

Student-customer analogy debate

There is a polarized debate in the literature regarding the appropriateness of considering students as customers, starting from whether universities should adopt the student-customer analogy to manage HE (Koris & Nokelainen, 2015). In favor of the mentioned analogy, Guilbault (2016) urges us to stop denying students are customers and instead recommends responding to their needs and opinions. Other authors have supported this idea, highlighting that universities face the challenges of a competitive market, such as the decrease in funding and student enrollment, so they must apply marketing strategies to achieve greater market share, just like any other organization (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, 2006; Su & Bao, 2001), considering students as the main customer and recognizing them as actors in achieving service quality, being HEIS the main responsible for generating strategies that enable student loyalty and retention (Hill, 1995).

In addition to the above, Petruzzellis et al. (2006) consider that universities should adopt the customer-student analogy due to the need to measure their performance through specific metrics, such as student satisfaction. Supporting the idea, Seeman and O'Hara (2006) proposed an information system focusing on the student as a customer and managing the interaction with all traditional issues -admissions, enrollment, and financial aid-, considering the importance of ensuring student satisfaction based on students' perception as an indicator of quality.

Even though several researchers advocate the practicality of the systematization of treating the student as a customer and some studies tend to point to education in terms of customer service -in key factors such as the satisfaction of students' needs and the development of innovative forms of education in the field of HE ecosystem-, it has also been mentioned that applying the same customer-business model in universities can severely damage education. For instance, and contradicting the student/customer treatment, several authors have mentioned that HE should not be seen from the general marketing perspective. Supporting this counter position, Driscoll and Wicks (1998) suggested that applying the customer-business marketing analogy to universities, comparing the educational experience to the commercial exchange of value, is dangerous for HEIS and opens the door to questioning their true purpose. Besides, Svensson and Wood (2007) emphasize that comparing students to customers when describing their relationship with universities is highly inappropriate, asserting that the student-university relationship is not limited to the purchase of a product and its use, as occurs in a customer-supplier relationship.

Supporting the approach that seeks to separate customer-business treatment from university management, Wueste and Fishman (2010) forcefully reject the use of customer service practice as applied to students, arguing that in most service areas customers can only determine their needs and pay for goods or services to satisfy them, which systematically contradicts the service nature of education, thus alerting HEIS of its adoption, since given the similarity of certain characteristics of HE with other services it could be very attractive to try to satisfy students' needs in the same way customers' satisfaction is sought. In this sense, Díaz-Méndez et al. (2019, p. 6) go further and argue that "the designation of students-as-customers is subject to problematic interpretations and may jeopardize the HE quality by directly affecting students' attitudes, understanding and motivations and distorting or impairing the quality of their learning experience, resulting in detrimental consequences for social development and educational sustainability due to the quality decrease training professionals at the university."

More recent evidence that identifies the negative consequences of said analogy can be found in the work by Bunce et al. (2017), who demonstrated the relationship between consumer orientation, student identity, and academic performance, which highly alerts that students who identify themselves as customers are often less likely to actively participate in the development of their educational training, since by assuming themselves as customers they expect positive academic results without participation, making professors responsible for their learning. Table 1 shows a summary of the major studies involved in this debate.

Table 1 Student-customer analogy debate.

| Research | Main concept | Author(s) | Year | Country | Journal | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The customer-driven approach in Business education: A possible danger? | Against student-customer and university-company analogy | Driscoll and Wicks | 1998 | Canada | Journal of Education for Business | 168 |

| Student satisfaction and quality of service in Italian universities | Universities need a customer-centric approach | Petruzzellis et al. | 2006 | Italy | Managing Service Quality: An International Journal | 504 |

| Customer relationship management in higher education | The student-centric focus improves customer data process management | Seeman and O'Hara | 2006 | USA | Campus-Wide Information Systems | 281 |

| Are university students really customers? When illusion may lead to delusion for all! | The indiscriminate use of the student/client treatment is inappropriate | Svensson and Wood | 2007 | Norway and Australia | International Journal of Educational Management | 280 |

| The customer isn't always right: Limitations of 'customer service' approaches to education or why Higher Ed is not Burger King | Customer service does not consider collaboration, participation, and reciprocity during the teaching-learning process | Wueste and Fishman | 2010 | USA | International Journal for Educational Integrity | 20 |

| The student-customer orientation questionnaire (SCOQ). Application of customer metaphor to higher education | Student/customer as customers in service activities, but not during academic activities | Koris and Nokelainen | 2015 | Finland and Estonia | International Journal of Educational Management | 68 |

| Students as customers in higher education: Reframing the debate | The student is the customer of the university but from the new conceptualizations of the customer role | Guilbault | 2016 | USA | Journal of Marketing for Higher Education | 163 |

| I can't get no satisfaction: Measuring student satisfaction in the age of a consumerist higher education | Student satisfaction is a key concept in the modern consumerist | Senior et al. | 2017 | U.K. | Frontiers in Psychology | 43 |

| The student-as-consumer approach in higher education and its effects on academic performance | Students who identify themselves as customers tend to perform less well academically | Bunce et al. | 2017 | U.K. | Studies in Higher Education | 483 |

| Improving society by improving education through Service-Dominant Logic: Reframing the role of students in higher education | Traditional management practices simplify the complexity of the educational service | Díaz-Méndez et al. | 2019 | Spain, Colombia, and U.K. | Sustainability | 9 |

| The student as customer and quality in higher education | The application of traditional management concepts represents a problem for educational quality | Calma and Dickson-Deane | 2020 | Australia | International Journal of Educational Management | 25 |

| Higher education's marketization impact on EFL instructor moral stress, identity, and agency | HE marketization limits professors from performing their tasks efficiently | Scott | 2021 | Thailand | ERIC Journal | 2 |

Source: authors.

There is a more equanimity analysis that has emerged, in which one seeks the clear identification of learners through a specific criterion of the different treatments they may be subject to during service experience. In this regard, Koris and Nokelainen (2015), after conducting a study of how students expect to be treated, conclude that the student-customer analogy is appropriate for specific facets of the university-student relationship, such as feedback, classroom studies, and staff communication, but not suitable for other processes, such as curricular design, rigor, classroom behavior, and graduation.

Towards the maturity of differentiating the debate, Senior et al. (2017) propose a hybrid model for the growth of HEIS based on a consumer approach, in which positioning HEIS in a market environment is fundamental, but without neglecting the aspects of regulatory oversight, among which the essential regulations of university behavior and rigor stand out. In this way, the authors emphasize the importance of avoiding generating a strict market relationship with students, considering them exclusively as a customer, understanding that this could be detrimental to their learning process. Furthermore, this hybrid model seeks a balance between the performance indicators expected from the market and students' natural position in the university.

Consistent with academic efforts to separate the management of students from that of customers, during the COVID-19 pandemic the limited or non-existing relationship between a customer and a student, as well as the management that both should be given, was highlighted with greater force. For instance, Calma and Dickson-Deane (2020) emphasize that students are different from customers, mentioning that the first are learners within the teaching-learning process and not buyers of an educational experience, so students' participation cannot be reduced to the purchase of education, but to explore, co-create and be co-responsible for the results obtained.

Finally, and within the context of HE marketization, as various authors refer to the business approach to educational management (Banwait, 2021; Gupta, 2018; Hurt, 2012; Judson & Taylor, 2014) that alludes to the customer/student analogy as a practice that seeks commercial benefits over the fulfillment of academic objectives, Scott (2021) points out that when students are assimilated as customers they want to be satisfied and not challenged, and hence they passively participate in an "entertaining" class discussion but without academic rigor.

Customer complaint behavior

When organizations identify and understand CCB they obtain information about their customers' perceptions, which is valuable for managing service quality (Goodman & Newman, 2003). For decades, CCB was largely defined under the perspective of goods-dominant logic (e.g., Gilly & Gelb, 1982; Singh, 1988), understood as a post-purchase activity whose study was focused on identifying and understanding the factors that motivate compliant behavior. However, from the SDL approach it has been understood that the complaint is not a specific moment but a dynamic process that takes place based on different factors such as the customer, service, situations, macro elements, attitudes and experience on complaint behavior, industry structure, and the vendor/product (Mousavi & Esfidani, 2013; Tronvoll, 2007).

Other research streams have focused on determining CCB types through various models (e.g., Crie, 2003; Singh, 1990). But for this study, Tronvoll (2007, 2012) research on CCB is particularly relevant, as it presents a CCB framework based on the SDL approach, contrasting the conventional CCB view as a static activity that takes place after the purchase with a different proposal claiming that CCB in which the exchange of goods is absent can be understood as a dynamic process that continuously adjusts and occurs during the interaction with the service. The author does this by presenting four narratives that show distinct types and interaction levels between the actors and the consumer's evaluation.

The narratives include shoes purchasing, a car rental, and cellphone purchasing, services in which there is a good that materializes the exchange temporarily or indefinitely, where the service is evaluated by a short human interaction or during the time of use. These services are marked by the "control" of the buyer and the limited level of relationship between the staff and the customer, with the most active relationship being that between the good and the consumer, thus leaving human relations in second place. However, the author presents a fourth service, HE, in which several actors are considered to participate in value co-creation during the interaction. In this type of service, the relationships between students and technologies are presented as secondary, placing the most relevant human relationships between students and professors. The narrative corresponding to the HE student -called customer by the author- underlines the high relationship between the university employees and the student in the service provision, in which students' participation is essential for the exchange and the result lies in students themselves and not in an exchanged or rented product.

The absence of goods exchange is a key element for the study of SCB, since this type of service involves a dynamic and highly interactive process throughout interaction. The study by Tronvoll (2012) shows that each service area has different levels of interaction, so the complaint should not be considered only as a post-purchase activity. In other words, Tronvoll (2012) mentions that the level of interaction and the actors involved during service processes are crucial for CCB treatment, applying the SDL approach, which is described as an interactive exchange process that starts after the value proposition from the service provider to the customer.

Therefore, CCB in a service where the interaction between actors and customers is high and property exchange is absent, is characterized by a dynamic and interactive complaint process resulting from consumer dissatisfaction during the period of the service provider's value proposition, service interaction, and usage evaluation. This contributes to identifying that the complaining behavior of the user (learner) of a service (teaching-learning process) does not happen at a specific point and does not occur for a particular reason, but integrally develops during the experience, of which students are co-creators and their level and quality of interaction are required.

Student complaint behavior in the literature

Unlike conventional customer service, students do not usually engage in formal complaint behavior when they experience dissatisfaction. This poses a challenge for HEIS, as it is more difficult for them to improve value propositions, adopt quality measures (Mukherjee et al., 2009; Su & Bao, 2001), and simply manage dissatisfaction. However, the fact that the tendency of students to formally complain is not significant does not mean they do not demonstrate their dissatisfaction using negative word-of-mouth actions (online/offline) through other instruments, such as anonymous student teaching evaluation surveys (Díaz-Méndez et al., 2017). This complaint has been potentiated within the digital and hybrid environment to which HEIS had to migrate during COVID-19. Given the above, the understanding of SCB is an element that impacts beyond student satisfaction (Su & Bao, 2001).

In the literature, the study of SCB has not been as comprehensive as that of CCB and has developed a rather limited theoretical framework. For example, Dolinsky (1994) applied an SCB framework exemplifying the value of the intensity of complaining behavior in a new study setting. The work considered variations in the complaint attributes, incidence components, the importance respondents attributed to their complaints, and their satisfaction with the outcome of the complaint. In a similar vein, Su and Bao (2001) presented a research on students' complaining styles, grouping them into three categories: passive receivers, private complainers, and vociferous complainers.

The result indicated that HE students do not tend to show their dissatisfaction through complaints, as there is a significant difference between the power and voice of the actors involved.

Beyond identifying key SCB elements, Hart and Coates (2010) developed an instrument to assess SCB, presenting a specific typology that they consider a taxonomy of complaint behavior oriented to the consumer, not precisely to the student. Their study explores the attitudes shown by East Asian students when they exhibit SCB towards HEIS. The authors conclude that students are not entirely comfortable with the customer label but are more likely to coin this concept when they require quick responses to their requests. Besides, they tend to complain through informal conversations rather than formal means.

There are other specific studies on SCB. For example, FitzPatrick et al. (2012) investigated Chinese international students, demonstrating that non-action responses can constitute a significant mode of complaining among this population. However, this is a reaction considered in a limited way by HEIS -even by those with established grievance processes. To identify the characteristics of emotions and the intensity of dissatisfaction experienced by students in "non-action," the authors argue the importance of an international education market and the deepening of "non-action" as a reaction to students' complaint behavior.

Another example is the research conducted by Ferguson and Phau (2012), which aimed to identify the attitudes and complaint behaviors that arise in students in response to a specific service in which they believe there is a failure. As a novelty, these authors provide elements that address various actions that students perform externally as complaining behaviors, such as web pages created to express their disagreement, online complaints, legal actions, and even changes in the university. These external actions are described as the third dimension of grievance behavior. Adding to the previous approach is the research developed by Chahal and Devi (2015), who developed a study to explore complaint attitudes of students towards service failures and the recovery strategies carried out by HEIS. Identifying service failure issues, whether by administrative or academic areas, emphasizes that when HEIS employ recovery efforts after a service failure they obtain significant results.

Recently, in building a deeper understanding of SCB, Yoke (2018) introduces another element based on the natural power of academics: the authority to influence student behavior is added to the HE compliant behavior. The relationship between a professor's perceived power, student dissatisfaction, and the way of complaining is demonstrated, pointing out a greater tendency to show a private or third-party complaining behavior in function of the perception of a professor's use and management of power.

Finally, and under the customer-student approach, Msosa (2021) analyzes students' perception of service failures and the CCB management system in the HE sector -specifically in South Africa-, highlighting the primary areas of service where students show complaints when faced with a situation of dissatisfaction. This author concluded that HEIS should pay special attention to students' needs, holding universities accountable for the use of value. Table 2 summarizes the studies described above.

Table 2 Studies on student complaint behavior (SCB)

| Research | Main concept | Researcher | Year | Country | Journal | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A consumer complaint framework with resulting strategies. An application to higher education | Academic reasons are the most common reasons for complaint | Dolinsky | 1994 | USA | Journal of Services Marketing | 152 |

| Student complaint behavior based on power perception: A taxonomy | Three types of complaining students are identified: passive, private, and vociferous | Su and Bao | 2001 | Canada | Services Marketing Quarterly | 26 |

| International student complaint behavior: How do East Asian students complain to their university? | Students often discuss their complaints among themselves, rather than to the university | Hart and Coates | 2010 | U.K. | Journal of Further and Higher Education | 25 |

| Chinese students' complaining behavior: Hearing the silence | The SCB responses and that these non-action responses had an affective dimension | Fitz-Patrick et al. | 2012 | New Zealand | Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics | 41 |

| A cross-national investigation of university students' complaining behavior and attitudes to complaining | The negative attitudes to complaining are positively related to remaining loyal | Ferguson and Phau | 2012 | Australia | Journal of International Education in Business | 21 |

| Consumer attitude towards service failure and recovery in higher education | All recovery efforts are significant in overcoming the respective service failures | Chahal and Devi | 2015 | India | Quality Assurance in Education | 30 |

| The interrelationship between perceived instructor power, student dissatisfaction, and complaint behaviors in the context of higher education | There is a relation between private complaining and third-party complaining with professors' legitimate power | Yoke | 2018 | Malaysia | International Education Studies | 2 |

| Service failure and complaints management in higher education institutions | Most of the students were generally satisfied with a complaints management system | Msosa | 2021 | South Africa | International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science | 2 |

Source: authors.

Higher education service ecosystem complexity

Several experts on marketing and pedagogy have agreed on the enormous difference between a university and companies, due to their complex structure and nature (Altbach et al., 2019; Díaz-Méndez et al., 2019). The complexity of HEIS management became more evident during the forced migration of activities to virtual and hybrid models due to the health emergency worldwide, given the difficulty involved in achieving a balance between students' needs and HEIS objectives, which created a dynamic and competitive scenario. Considering this phenomenon, Shupe (1999) highlights the challenge of managing the organizational context of HE, since among universities there is a diverse understanding of who the producer is, what the process is about, what the product is, and even who the customer is. Douglas et al. (2008) analyzed student satisfaction and considered HE a complex entity due to its intangible nature, added to the challenge posed by the multiple relationships between actors such as students, parents, government, industry, and alumni.

The multiple relationships involved in the HE service creates several challenges. In this regard, some authors have emphasized the high potential for failure in this service, since what universities provide to their students is a complex service that includes a wide range of outcomes and different perspectives for evaluation (Iyer & Muncy, 2008; Pucciarelli & Kaplan, 2016). Adding to the previous idea, Wueste and Fishman (2010) emphasized the complexity and the existing differences between HE and other services, presenting a study that explains why HE cannot resemble a restaurant, strongly pointing out that acquiring knowledge and skills cannot be equated to buying a hamburger.

The complexity of HE and its proper management is not limited to the aforesaid but there are other aspects to consider, for instance, the singular disparities in the relationship university-student and customer-company. In this regard, Díaz-Méndez and Gummesson (2012) describe relevant differences between HE service and others, such as the fact that in most services customers do not expect that the supplier evaluates them with a test, or that in no other service the relationship finalizes with the assignment of a mark based on customer performance, as it occurs in HE. These authors add to the discussion on HE service complexity how in a common commercial relationship customers expect a result in exchange for the money they have paid, whereas students who have paid for an educational service and those who have not -for various reasons- also expect a result, in this case, knowledge and skills.

Strengthening the arguments of educational complexity, Díaz-Méndez et al. (2017) expose that, unlike other services, HE is by nature a pillar of social development, so its value is not related to the payment given for the service, since the perception of payment is influenced by different variables -such as the nature of universities, which may be public or private, as well as scholarships and other funding programs obtained by students, university fees established by each country, etc.- that can distort the perception of payment and, therefore, the perceived value of a service.

The complexity described above highlights the need to find management approachable to deal with it so that all factors and actors interacting in the service may be harmoniously involved in a service system designed to create value for all parties. This reflection study agrees on the complexity of HE due to the role it plays in human development, a complexity that increased when its traditional inperson methodology migrated to virtual or hybrid models, so that HEIS faced the behavior of student complaints in the way organizations and companies do, following marketing perspectives that do not necessarily result suitable to HE. Such strategies could help to ensure the permanence of students, but not their learning, which does not meet the primary objective of HE and thus undermines its sustainability.

Value co-creation in the higher education service ecosystem

This work argues that SCB treatment should be better addressed through the value co-creation perspective from the SDL approach, as several academics and marketing experts have supported, but in a different way than the CCB framework, considering the service ecosystem's complex nature, as this approach considers the interaction among actors and acknowledges that HEIS propose a value, where students have the primary role in achieving the expected value. The value co-creation perspective goes beyond the consumer orientation of marketing and implies a constant collaboration between HEIS and the student so that universities learn from their students and their needs, suggesting that this value is ultimately defined by all actors and resources in the ecosystem (Smørvik & Vespestad, 2020; Vargo & Lusch, 2017).

The value co-creation axioms applied to the HE context allow us to understand that value is achieved only when it is in use and co-created by students together with HEIS, hence, the study of SCB based on the co-creation process should be perceived as a dynamic process of joint involvement (Tronvoll, 2007; Vargo & Lusch, 2017). In addition, in this dynamic SCB the quality and depth of the interaction between the actors is the essence of the service exchange, since the expected result (learning) is reflected in the transformation of students themselves, through the achievement of professional and disciplinary skills. However, when students experience dissatisfaction due to a situation that -from their judgment and perspective- they consider is not adequate, it gives way to a complaint behavior that must be managed considering that their participation and contribution to the collegiate work have a direct influence on the result obtained, i.e., students are co-responsible for the results obtained during HE-related activities.

The development of this research focuses on the applicability of the value co-creation axioms of the SDL approach (Vargo & Lusch, 2017; Vargo et al., 2020) specifically suitable for understanding the dynamic process of SCB: axiom 2/FP6, value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary; axiom 4/FP10, value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary; and axiom 5/FP11, value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements. These axioms are appropriate to consider the complexity of HE service and the difference between the nature of a student and that of a customer.

Axiom 2/FP6: Value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary

There are few services in which the beneficiary acts as co-creator of most of the expected outcomes -before, during, and even years beyond the service is over-, and HE service is one of them (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, 2012; Dollinger et al., 2018; Golooba & Ahlan, 2013; Judson & Taylor, 2014).

Just as insofar a hospital patient follows a doctor's recommendations to achieve a favorable outcome, it is the learner who largely determines the knowledge acquired (Lala & Priluck, 2011; McCabe & O'Connor, 2014). Hence, is possible to affirm that HE service is co-created in its nature, which means that there is no remote possibility for students to obtain a degree without showing their active participation.

In the emergent e-learning or hybrid methodology applied by many HEIS due to the health emergency, students should be assumed as active actors that dynamize the teaching-learning process through their constant participation as co-creators, co-designers, and co-producers of the academic sessions (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, 2018; Bovill & Bulley, 2011; Haraldseid-Driftland et al., 2019), which demands a self-taught act and the development of applied critical thinking within the professional context of their discipline to appropriate knowledge that will lead to acquiring professional skills (Meyer & Norman, 2020; OECD, 2008). However, when the results for which the student is responsible are not as expected and generate a complaint behavior regarding not achieving the objectives, unlike the customer of a service, its treatment and management should be based on their participation as a student, not only in the performance of faculty members or the other actors of the ecosystem.

Axiom 4/FP10: Value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary

Learning as a value is the result of the integration of the ecosystem's resources, thus allowing students to achieve their academic and disciplinary objectives. This value is phenomenologically determined by each actor in their social context and tells us that students' quality perception of the teaching-learning process will be based on their experience and will be different from the professor's perspective and even from their classmates' perception (Tomlinson, 2018; Vargo et al,, 2020).

In addition, this axiom highlights that the achievement of academic goals through the implementation of teaching strategies by professors mostly familiar with face-to-face teaching, who had to adapt their work to a digital/hybrid methodology, also depends on the joint participation of the actors involved and is achieved by co-creating value based on the student, the professor and, in general, HEIS social context, so that value co-creation will have different and various valuations (Leem, 2021; Perla et al., 2019). In this sense, when students experience a negative experience in the teaching-learning process, social context plays a significant role, and not only faculty performance (Lei & So, 2021; Vargo et al,, 2017).

Axiom 5/FP11: Value cocreation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements

The SDL argues that in addition to HEIS social structure, value co-creation will also be achieved as the complex system of institutional agreements converges and manages to permeate all the actors involved, so that the contingent nature of the value can be identified based on the integration of resources (infrastructure, technology, knowledge) and actors (students, teachers, managers, support staff, etc.) (Gaebel et al,, 2018; T0mte et al., 2019).

Institutions and their arrangements play a relevant role in value co-creation during the service exchange, since it is precisely these institutions, through the coordination of all the actors, who allow these actors to achieve increasing returns through interrelationships, even more so in turbulent periods such as the COVID-19 international contingency, in which each actor required precise guidelines regarding their participation (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Marinoni et al., 2020). Then, according to Vargo and Lusch (2016), the arrangements that universities as institutions offer should be materialized into a value proposition through educational services that meet the expectations of university students.

A conceptual framework proposal to student complaint behavior (SCB)

The uncertainty and unprecedented period lived by humanity required the implementation of theoretical approaches that contribute to addressing the changes in students' habits and behaviors, promoting better management practices and service sustainability. In this scenario, value co-creation from the SDL approach is a strategic theory for understanding SCB. Therefore, and given that universities are the ones that generate the value proposition during the training of human capital, this approach has been adopted for their management processes (Gummesson et al., 2010; Stimac & Simic, 2012). However, even though the SDL has been widely implicated in educational services, academic training and research (Ford & Bowen, 2008; Gummesson et al., 2010; Smørvik & Vespestad, 2020), few studies have adopted this perspective to understand SCB (Gillespie & Zachary, 2010; Tronvoll, 2007).

In addition to emphasizing the nature and elements of the HE service ecosystem and the value co-creation process, the authors of this paper agree with Tronvoll (2012), who identifies SCB as a dynamic behavior that occurs during value-in-use, not just post-value-in-use, and that simultaneously or separately results in a set of value-in-use experiences for the learner. Such an experience perceived as unfortunate, within the HE dynamics, happens mostly in the short term, possibly following a teaching-learning process that has been designed to achieve value co-creation in the long term, but in immediacy may generate some discomfort. Exemplifying the above, it is possible to find certain similarity when a doctor injects the patient, "generating discomfort at the moment" to achieve a benefit in the long term, so that if the service experience is only evaluated based on the static moment of the injection, the patient will surely describe it as an unfavorable experience.

Just like in the previous example, throughout the HE service experience the student first goes through a natural process of "discomfort" in the short term, due to the development of unfamiliar or challenging academic activities (Diaz-Mendez & Gummesson 2012). Nevertheless, without student participation there is no professional training, since students construct their learning and are responsible for their education through feedback, opinions, and their intellectual skills exposed during the teaching-learning process (Dollinger et al., 2018). In other words, students are precisely who phenomenologically determine their learning and the development of professional competencies, whose results will be observed mostly in the long term. As a result, we understand that the student is partially responsible for the negative experience that leads to a possible complaint.

During the time-of-service provision (years), especially during the virtual/hybrid methodology learning curve, the student may live one or several negative experiences, depicting a passive or active complaint behavior towards a third party (Hart & Coates 2010). This negative experience maybe a teaching strategy that was not understood by the student or an element of the ecosystem that is not in the hands of the professor, for example, educational platforms, internet connection, content, or HEIS administrative and management policies (Karunathilake & Galdolage, 2021). As analyzed from the value co-creation perspective, specifically from the SDL axiom 5/FP11, HEIS, as a set of human resources and capabilities, coordinate the service experience through various actors and institutional arrangements. Therefore, when understanding and managing SCB, the intervention and regulation of institutional arrangements and agreements that dictate the guidelines to check on the performance of students (beneficiaries) should not be neglected.

In line with the previous insights, axioms 2/FP6 and 4/FP10 help to understand that value co-creation in a complex ecosystem such as that of HE implies an intellectual effort by students so that they can co-create value, an effort much more complex than that made by a customer when buying a pair of shoes or acquiring a telephone service. The co-creator student needs self-preparation before the sessions, a level of information analysis, and an understanding of academic and scientific texts, as well as the application of theoretical knowledge in practical situations. In any other type of service, the beneficiary is not expected to bring this level of depth and commitment to achieve the expected value. HE students are, therefore, co-responsible for the experience that triggers or conditions the dissatisfaction or non-satisfaction causing their complaint.

SCB is an essential element in identifying areas of opportunity for universities as providers of educational services and managing student satisfaction. Consequently, an appropriate way to manage SCB seems to be the value co-creation perspective from the SDL approach, considering the dynamism of the educational service, the complexity inherent to this, the roles, characteristics, and interests of the interacting actors, and especially valuing the unique role of the student. Figure 1 represents the SCB process based on this value co-creation perspective and the service complexity.

Discussion and conclusions

This reflection article critically analyzes the problem of the increasing standardized treatment of SCB within HEIS by reviewing relevant literature that addresses the debate on the student-customer analogy and the complex process of value co-creation that represents the nature of the higher education service, highlighting that, unlike other service ecosystems, in universities, students must contribute their intellect, disciplinary skills, and specialized knowledge to achieve the expected benefits and therefore become co-responsible for the efficiency of teaching-learning activities and their outcome, whether satisfactory or not.

Although there is an academic effort to consider students' participation in the results obtained during the service experience, HEIS continue to exclude the student from such responsibility. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the tendency to HE marketization strengthened a practice that indiscriminately applies the student/customer analogy, simplifying the processes of attention through a quick response that dissociates students from the causes or reasons that could cause dissatisfaction or non-satisfaction. This educational marketization has been strongly criticized by academics, generating rejection towards the use of service strategies in the management of SCB by various experts in education and teaching, even calling on HEIS not to consider marketing in HE. However, this position distances SCB management from the marketing sphere and omits the fact that HEIS are also immersed in a competitive market in which it is essential to create important competitive and differentiating advantages, especially when trying to attract and keep students and even more so in a turbulent time such as the pandemic period.

Faced with the crossroads between managing the SCB considering students' performance or disassociating it from their role as co-creators to ensure their immediate satisfaction, and possibly their permanence, this paper contributes to the development of the synergy between marketing and its involvement in HE management, seeking an innovative perspective that leaves behind the idea of understanding students' complaints separated from their performance, for an application perspective in which the complaint may be understood as a dynamic process in which the student is the main actor and, therefore, co-responsible for the results, without leaving aside the interference that HEIS, their policies and regulations have on service efficiency. To manage the SCB within the marketing framework, but in a different way from that of customers, the authors of this work integrate the model of complaint behavior and the perspective of value co-creation that is explained by three fundamental premises of the SDL, highlighting the complexity of the HE service and its social value, to achieve student satisfaction without undermining the sustainability of universities in the long term.

Although SCB has been studied within the framework of SDL, it has not been done separately from CCB, hence several authors have considered the immense disparities between SCB and CCB, focusing SCB management on the adaptation of CCB models in other service areas. Because of this, and even though scholars have developed some specific research and a limited number of models especially for students, as unique users of the service, this field of study is still broad. Another factor that HEIS must consider when managing their students' complaints, besides the differences between the client and the student, is the complex and multifactorial system of interaction and co-creation of value in the teaching-learning process. This co-creation process is different and unique because of the social value it represents, as it is through this pillar of development that societies seek to improve their economic, technological, and scientific conditions.

Considering that a student's complaint is multifactorial and arises from a co-responsibility between the institution and the complainant, this behavior becomes intrinsically complex, as so is its treatment. However, the effective management of SCB brings multiple benefits to organizations, since, from a verbal or non-verbal complaint, it is possible to obtain important information to improve the service experience and pursue student satisfaction both in the short and long term, when the pursued HE value is mostly achieved. In other words, if HEIS manage to efficiently incorporate students and their participation as co-creators, the treatment given to complaints will be focused on improving the experience in which they are participants.

Our work is consistent with Tronvoll's (2012) in situating SCB within the SDL perspective, specifically within the three axioms that explain value co-creation as a dynamic process in which different actors interact through their skills and knowledge to generate synergies with material resources such as technology and processes. However, our findings are expanded by separating the student from the standardization of the customer in other services, as followed by researchers such as Bunce et al. (2017) and Calma and Dickson-Deane, (2020), but without leaving aside the relevance of marketing strategies in the management of education, as suggested by studies focused on value co-creation within the higher education service ecosystem, such as the works by Dollinger et al. (2018) and Msosa (2021).

The reflection presented in this paper is circumscribed to specific Latin American educational contexts and their structures, as well as its preliminary conclusions. Accordingly, future studies are required to follow up on the management of SCB under the perspective of value co-creation in post-pandemic times. As an example, a future line of research can delve into the generation of a SCB model that combines some specific elements of CCB with those of SCB, considering the educational ecosystem and the new post-pandemic scenario, in order to improve the management of university complaints by avoiding quick and standardized responses that privilege the fulfillment of student recruitment objectives but not academic goals, which would trigger the generation of satisfied students in the short term, but professionally incompetent in the long term, thus leading to questioning the reason for the existence of universities.