Introduction

The relationship between consumers and brand communications has been widely studied (Kumar & Kaushik, 2020; Laroche et al., 2013). Companies intentionally seek to create cohesive brand messages across online, offline, and mobile communications (Bleier et al., 2019; Jensen, 2007). Brand communications are deployed to obtain sustainable competitive advantage (Majerova & Kliestik, 2015), i.e., by allowing companies to engage customers, inspire loyalty, and earn larger margins (Hoeffler & Keller, 2003). The tone used by a brand influences all those who view the message, which indicates the importance of being strategic when composing a brand tone during a social crisis. Beyond the traditional marketing goals of generating customer delight and enthusiasm, brands are developing communication tactics to support customers in an increasingly uncertain and turbulent world (Hess, 2020; Hus, 2020). This present study is valuable because it investigates consumer preferences for brand tone when they are in a stressful situation (i.e., lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic).

The pandemic created a wide variety of stress concerns for consumers (Pfeifer et al., 2021). Stress is often defined as a state where perceived concerns or demands exceed personal resources, causing an individual to have a neuroendocrine reaction (Lazarus, 1993). After the start of the pandemic, American consumers' stress levels significantly increased (Canady, 2020), and depression rates rose by seven percent (Torales et al., 2020). Recent research has investigated brand communications in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Brands in many industries were applauded when they shifted from emphasizing entertainment and enjoyment to guiding and protecting consumers during a severe pandemic crisis (Pompeu & Sato, 2021). Furthermore,

It has been suggested that change in the traditional role of advertising communication has occurred, where advertisers have become a key support in combatting the disease and a key support for health and psychological management in the Spanish population. In fact, they act as guardians of resilience and promoters for alleviating stress. (Olivares-Delgado et al., 2020, p. 1)

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed how consumers act (Anderson et al., 2020). Hollebeek et al. (2020) found that consumers welcomed using alternate messages and delivery platforms during the pandemic. By broadcasting their protective measures against the virus, physical stores elicited positive consumer attitudes and intentions to purchase, especially for female customers (Untaru & Han, 2021). Clear communication of enhanced cleaning protocols via brand messaging outlets was a critical component. Some sectors, e.g., the travel industry, had the potential and possibly a moral imperative to become a critical source of COVID-19 information for potential travelers and citizens (MacSween & Canziani, 2021).

To further this line of research regarding the viability of specific brand tones in crises, we captured the brand tone preferences of consumers during the initial COVID-19 lock-down period in the U.S. Five mutually exclusive brand tone choices were presented to consumer respondents (informative, comforting, trustworthy, inspiring, and humorous), and consumer preferences for these were inspected.

Following seminal work on coping strategies, this paper adopted the view that coping can be a process consisting of cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage perceived stress from the pandemic (Lazarus, 1993). Thus, consumers' stress levels and coping strategies during the COVID-19 crisis were measured to explore their relationship to brand tone choice. To the extent that consumer preferences for brand tone are diverse within the pandemic situation, companies have the obligation to match their clients' tonal needs. However, individual brand tones are expected to associate differently with the level of pandemic-induced stress reported by respondents in this study. One of our brand tone types represented what we considered a neutral (informative) brand tone and was not expected to interact with stress per se since information search is a common consumer strategy in most situations. Next, we anticipated that stress would have a positive relationship with each of three brand tones meant to ease or reduce consumer-experienced stress during the pandemic (comforting, trustworthy, and inspiring). A fifth option, an incongruous tone choice (humorous), was expected to be inversely associated with consumers' stress levels. Specific research propositions follow:

R1: Pandemic-induced stress will have no significant association with preferences for an informative brand tone.

R2: Pandemic-induced stress will have a positive association with preferences for comforting, inspiring, and trustworthy brand tones.

R3: Pandemic-induced stress will have a negative association with preferences for a humorous brand tone.

Considering behavioral tactics for coping, the authors accessed two other data types: stimulus funds use and voluntary relaxation activities during the lockdown. These were explored in terms of their associations with brand tone selection. Finally, this study considered demographics in the context of brand tone preference. Further research propositions were proposed, designed to reflect the very exploratory nature of our study:

R4: Stimulus expenditures will have an association with brand tone type.

R5: Relaxation preferences will have an association with brand tone type.

R6: Demographics will have an association with brand tone type.

Literature review

Brand tone defined

Various means convey a brand's image: company name, logo, symbol, slogan, character spokesperson, or even a jingle (Grewal & Levy, 2022). Companies have recognized the importance of brand signs and symbols as crucial intangible assets (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). A brand tone encompasses the words chosen and communication of the brand's intentions toward its audience, including all text, images, and audiovisual materials (Jabreel et al., 2017). Multi-channel communications with consumers are strategically managed by brand managers who develop the tone of the messages. Our study defines tone as the alternative emotional characters that a brand intentionally uses to communicate with consumers. The underlying assumption is that the COVID-19 pandemic may influence preferences for alternate brand tones, such as comfort or inspiration. Respondents were asked to identify a single personal preference for one of five unique brand tones that brands could use during the pandemic. We now define each of these brand tones in turn.

Informative brand tone

Some people prefer rational and informative messages and others prefer emotionally loaded or hedonic messages (Freitas & Ribeiro-Cardoso, 2012). Generally, a brand tone can be perceived as informative if it is relatively emotion-free and factual (Janssens & Pelsmacker, 2005). Informative brand messages have been found to increase awareness of brands (Tsai & Honka, 2021). De Keyzer et al. (2017) found that a factual tone positively impacts the brand's attitude in conveying the message and driving purchase intention. An informative tone during the COVID-19 situation might be used to influence purchase intention (i.e., permitting consumers to compare information on and buy cleaning products to kill viruses).

Comforting brand tone

A comforting brand tone is one where consumers feel that businesses are empathic about customer needs (Arief & Pangestu, 2021). Brands that understand the emotions of their customers and respond with empathy are rewarded with a stronger emotional connection (Gupta & Nair, 2021). The use of an empathic and comforting brand tone has evolved to include creative messages and social media communication strategies (Zaharopoulos & Kwok, 2017).

A lack of empathy can negatively impact the company and its customers, while a comforting brand tone can enhance the brand's reputation (Allard et al., 2016; Baker, 2017; Yoon et al., 2018). COVID-19 prompted companies to move towards a more empathetic understanding of their customers (Mocanu, 2020). Comfort has a significant function in reducing stress, which applies to the present study.

Trustworthy brand tone

This brand tone derives from an increasingly important concern in marketing, especially as digital commerce expands across the globe, i.e., establishing a brand worthy of consumer confidence, including all of its operations, formal/informal guarantees, and management of consumer touchpoints. Trust is defined as a customer's willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on an honest, reliable, and open relationship (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2000). Being trustworthy starts with the quality of the core product but extends to staff behavior as well as the safety and security of the purchase process and other encounters involving the consumer/user (Gupta & Nair, 2021). Trust is also built through the quality of the brand message (Velly et al., 2016).

Consumers want to interact with trustworthy brands (Gupta & Nair, 2021). Eberhardt et al. (2020) found a direct impact on purchase intention and a consumer's view of information trustworthiness. Examples of its relevance in the pandemic era are company promises of relaxed refunds and easy schedule changes when the virus impacts consumers' planned travel and event attendance. Food brands intentionally constructed brand messages to encourage trust in their delivery services. Pizza Hut ran an ad stating that their delivery employees washed and sanitized their hands every 30 minutes (Gupta & Nair, 2021).

Inspiring brand tone

This brand tone challenges consumers to look deeper at their goals for affiliating with the brand from a different angle or perspective than they might have initially done. Brands that inspire tend to have a lasting impact on their customers and the greater society. Social marketers have benefited from inspirational content, e.g., in establishing anti-smoking campaigns that inspire smokers to quit (Lupton, 2015). Health service companies seek to develop messages encouraging patients to adhere to medication schedules or wellness behaviors. Petrie et al. (2012) reported the positive impact of text message communications to asthma patients, prompting continued use of a preventive inhaler. Over recent decades, many companies have encouraged their consumer base to be conscientious in adopting principles of sustainability and responsible consumption (Payne, 2012). In the pandemic context, an inspiring brand tone could be exemplified by advocating for activities that protect the health and wellness of society, such as wearing masks and proper handwashing. Companies also crafted messages to encourage consumers to care for their physical and psychological health during the pandemic (Olivares-Delgado et al., 2020).

Humorous brand tone

Humor is the most widely used form of emotion in brand communication (Schiffman & Wisenblit, 2019; Thomas & Fowler, 2021). This brand tone can encourage positive and negative responses (Cifuentes & Sánchez, 2006; Yi et al., 2020). Compared to a neutral brand message, a humorous brand tone influenced brand recognition and intention to purchase; however, it had no impact on brand recall (Cifuentes & Sánchez, 2006). Many studies have explored the impact of diverse types of humor on brand recognition and purchase intention. Humorous allusions (indirect references to some idea, figure, other text, place, or event that originates from outside the brand context) had the greatest impact on purchase intention (Cifuentes & Sánchez, 2006). Humor with a hostile or incongruous tone also created a positive view of the brand. Incongruous humor drives the intention to purchase by arousing consumer engagement (Ribeiro et al., 2019). The placement of humor in brand messages has also been studied. When humor comes after the principal message, it has a positive impact on purchase intention (Teixeira et al., 2014).

Some companies have used a humorous brand tone to help customers manage stress during the pandemic (Gupta & Nair, 2021). Progressive Insurance had a series of video advertisements showing characters Flo and her colleagues struggling comically to use Zoom® for virtual meetings. The first commercial aired in April 2020, at the start of the pandemic (Progressive Insurance, 2020). Even though humor is a popular form of communicating fun and excitement to customers, its role during the high-stress pandemic is uncertain at best.

Profiling who likes what brand tone during the pandemic

The present study is important because it explores connections between consumers' feelings about health, financial and personal/family pandemic stress concerns, and the brand tone they preferred companies to use at this challenging time. In addition, demographic measures and behavioral coping strategies were analyzed against brand tone to examine further the consumers who preferred specific tonal alternatives.

Pandemic stress concerns and brand tones interaction

To operationalize stress in this study, we characterized the pandemic as a major stress event occurring in everyday life. Global life stressors tend to persist over more extended periods and lack a clear beginning or ending with stronger perceived impacts, possibly due to increased personal relevance and a higher intensity of negative concerns (Kar et al, 2020; Pfeifer et al, 2021). According to Pfeifer et al. (2021), the COVID-19 pandemic can be considered an excellent opportunity to assess stress in a field context, i.e., through self-reports rather than an experimental one. Stress concern items were extracted from multiple sources (Avena et al., 2021; Hagger et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2020).

Conceptualizing coping

Coping with pandemic stress has been an ongoing situation for people worldwide. We wondered if certain coping tactics aligned with specific brand tone preferences. Existing literature on this topic confirmed that coping may be a cognitive or behavioral process. Lazarus (1993) further clarified that "from a process perspective, coping changes over time and in accordance with the situational contexts in which it occurs" (p. 235). One coping strategy that was unique to the coronavirus pandemic was the use of U.S. government-issued stimulus funds. The data collected permitted breakdowns of stimulus use into necessary versus non-essential purchases, following thinking in Di Crosta et al. (2021). Secondly, various sources adapted relaxation items (Fullana et al., 2020; Morse et al., 2020; Rivas & Biana, 2021). Results and discussion identify the coping strategies and demographic profiles of people using the different brand tones described previously.

Gender and brand tones

Gender is widely studied as a factor in communication studies. Female journalists provide media coverage with more positive framing, especially regarding stories about women (Shor et al., 2019). The gender identity of a social media profile impacts viewer engagement; for example, men and women responded differently to gendered profiles on Facebook. Men resisted interacting with brands with a feminine profile; women accepted both feminine and masculine profiles more readily (Machado et al, 2019). Other studies have shown that males and females prefer different types of information when shopping. Men prefer a rational message (i.e., informational brand tone). At the same time, women respond to an experiential message (i.e., humorous, inspiring, and comforting brand tones) when searching for products (Sladek et al., 2010). Men overwhelmingly prefer messages comparing brand benefits (i.e., informative brand tone) versus their female counterparts (Chang, 2007; Petrovici et al., 2019).

Gender can indirectly influence brand tone preference since genders may not be equally stressed by the pandemic. Men and women were impacted differently by COVID-19. Mothers were hit hardest during the pandemic due to disparate childcare-work responsibilities (Collins et al, 2020). Many women had to change their employment status due to reduced childcare and virtual schooling (Petts et al., 2021). Unfavorable employment outcomes were reported for mothers with school-age children but not their spouses (Petts et al, 2021).

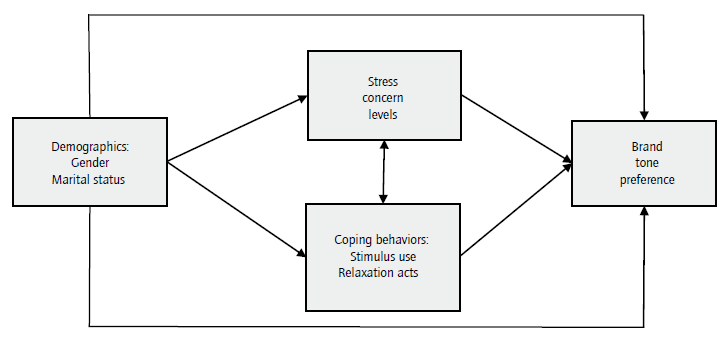

Women reported higher levels of anxiety for the pandemic than men (Rodriguez-Besteiro et al., 2021). Women from a lower socioeconomic status were more likely to be depressed, especially those females who are heavy social media users (Mowbray, 2020). This highlights the importance of brand tone for them during this stressful time. Given these reports of gender imbalances during the pandemic, the present study also investigated the preferred brand tone by gender and the marital status during the early stages of the COVID-19 period. Figure 1 displays the important focus areas of this study.

Methods

Sampling and data collection

We obtained secondary data from a local marketing firm that collected responses from panelists (Prime Panels) residing in the United States (Smith et al., 2016). Prime Panels have been used in prior studies to assess the general U.S. population (McCredie & Morey, 2019). Screening limited age to 18 or above. Data collection took place over a two-day span in April 2020 with minimal quotas for gender, age, education, and income. Survey-taking averaged 9 minutes, with a standard deviation of 6 minutes. The marketing firm checked response quality for speeding and straight-lining and performed initial recodes. The data set of 546 records was then provided to the authors for their research use.

Survey instrument

Table 1 provides examples given to respondents to demonstrate how brand tones have been used during the pandemic. Before issuing the main survey, a manipulation check using undergraduates verified that respondents could discriminate among brand tones. Beyond asking about brand tone preference, additional primary data of interest included items related to concerns about the effects of COVID-19 on family, financial, and health situations, relaxation tactics while sheltering in place, and preference for brand communications tone during the pandemic. Age, gender, race/ ethnicity, household income, education, marital status, and children were documented.

Table 1 Definition and examples to discriminate among five brand tones.

| Brand tone | Definition | Message example |

|---|---|---|

| Informative | Factual messages intended to share knowledge with consumers, generally to support a purchase decision. | Procter & Gamble aired a Super Bowl commercial to promote the long-lasting benefits of its Microban 24 sanitizing spray, which competes with Lysol disinfectant spray (Neff, 2021). |

| Comforting | Designed so consumers see businesses as being empathic and caring about their needs. | In a Domino's pizza ad, they announced that they are hiring. "If getting some full- or part-time work during these tough times could help you, Domino's is hiring... We're committed to helping you put food on your table" (Peters, 2020). |

| Trustworthy | Intended to instill consumer confidence in the brand as well as in its products, people, and processes. Takes the form of a guaranteed message. | "When you need a vehicle you can count on, trust Toyota to be here for you... It's our promise to you." The automaker states that many service centers remain open with no-contact vehicle drop-offs (Peters, 2020). |

| Inspiring | Challenges consumers to look deeper at their goals for affiliating with the brand. This brand tone encourages people to improve themselves and the world around them. | Coca-Cola Nigeria deployed a campaign founded in the promise of new possibilities discovered through lockdown, i.e., Open, Like Never Before... "Open Like Never Before is founded in the belief that we do not have to go 'back' to normal... Instead, we can all move forward and make the world not just different, but better" (Onwuaso, 2020). |

| Humorous | Comical situations or jokes intended to distract or lighten a consumer's mood. | Progressive insurance showed an ad where employee Mara is unmuted during a Zoom call, making ironic comments outside the context of the work meeting to some invisible person behind her (Progressive Insurance, 2020). |

Source: authors.

Analysis

SPSS was deployed in the statistical analysis of the data, using primary techniques for comparative analysis. The general intent of the analysis was to contrast characteristics and pandemic reactions of individuals grouped by their brand tone preferences to better understand preferences for certain communication tones in times of crisis.

Results

Description of respondent profile

Men composed 49.2% of the sample, with women at 49.5%. The dominant ethnicity was White (72.0%), with 9.5% of the sample identifying as Hispanic/Latino, 7.1% choosing Black, and 6.6% selecting Asian. Considering age, the highest percentage (41.5%) fell into the 25 to 34-year-old category, followed by 23% in the 35 to 44 age category. Most participants had a bachelor's degree (52.3%) or higher (21.7%). A higher number were married (59.4%), followed by single, never married (32.5%). Over half of the respondents had children under 18 (59.6%). More respondents resided in California (13.9%), Texas (9.3%), New York (7.5%), and Florida (6.9%), with all other states except Alaska represented in the sample. The modal income category was USD 50,000 to 69,999.

Brand tone preference results

Respondents exhibited different brand tone preferences during the pandemic, with the following proportionality: informative (32%), comforting (21°%), trustworthy (18.3%), inspiring (14.4%), and humorous (14.1%%). Additional comparative analysis was conducted to glean more profound insights into our first research objective, i.e., to determine any respondent characteristics that might associate with specific brand tones.

Stress and brand tone preference

Additional analysis was performed to assess if consumers might be seeking particular brand tones to offset or compensate for experienced stress during the pandemic situation. First, several concerns were examined (table 2), encompassing general feelings about the pandemic, immediate health stressors, financial concerns, family issues, and personal concerns regarding alcohol and body weight. As noted, two overall concerns were assessed, i.e., concern with the overall pandemic and the current state of the economy during the pandemic. While most respondents showed concern over 4.0 on a five-point scale, those indicating a preference for a humorous tone had significantly lower mean scores on these two general pandemic concerns.

Table 2 Concerns during the pandemic associated with brand tone preferences.

| Brand tone preference types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern type | Informative (n = 175) | Comforting (n = 115) | Trustworthy (n = 100) | Inspiring (n = 79) | Humorous (n = 77) | ANOVA* |

| COVID-19 concern | 4.01 | 4.06 | 3.66 | 4.05 | 3.53a | F(4, 534) = 5.126, p = 0.001 |

| American economy | 4.13 | 4.17 | 3.96 | 4.09 | 3.69a | F(4, 539) = 3.816, p = 0.005 |

| Getting the virus | 3.31 | 3.39 | 3.22 | 3.17 | 3.06 | F(4, 540) = 1.129, p = 0.342 |

| Testing availability | 3.18 | 3.16 | 3.15 | 3.13 | 3.04 | F(4, 537) = 0.158, p = 0.959 |

| Medical care | 3.10 | 2.98 | 3.09 | 3.13 | 2.94 | F(4, 535) = 0.356, p = 0.840 |

| Rule compliance | 3.46 | 3.67 | 3.45 | 3.46 | 3.19 | F(4, 540) = 1.582, p = 0.178 |

| Employment status | 2.66 | 2.89 | 3.08 | 2.84 | 3.03 | F(4, 537) = 1.732, p = 0.142 |

| Paying bills | 2.93 | 2.95 | 3.04 | 3.01 | 3.07 | F(4, 532) = 0.195, p = 0.941 |

| Food accessibility | 3.04 | 3.15 | 3.22 | 3.20 | 2.99 | F(4, 539) = 0.668, p = 0.641 |

| Losing money | 2.47 | 2.15a | 2.84 | 2.77 | 2.45 | F(4, 539) = 3.714, p = 0.005 |

| Retirement issues | 2.62 | 2.40 | 2.88 | 2.45 | 2.77 | F(4, 537) = 2.058, p = 0.085 |

| Juggling family/work | 2.54 | 2.45a | 2.97 | 2.97 | 2.35a | F(4, 540) = 4.064, p = 0.003 |

| Schooling issues | 2.33 | 2.05a | 2.87 | 2.87 | 2.30 | F(4, 537) = 6.430, p = 0.001 |

| Other family issues | 2.65 | 2.20a | 2.85 | 2.84 | 2.67 | F(4, 535) = 3.858, p = 0.004 |

| Alcohol consumption | 2.06 | 1.77a | 2.59 | 2.33 | 2.49 | F(4, 539) = 6.287, p = 0.001 |

| Weight issues | 2.60 | 2.42a | 2.89 | 2.60 | 2.93 | F(4, 538) = 2.436, p = 0.046 |

*Comparison among the five brand tone preference groups; aPer Games-Howell post hoc, significantly different from one or more other groups at p < 0.05.

Source: authors.

While specific concern with health issues was moderate in this study, hovering at the midpoint of 3 or above, there was no association between health concerns (getting the virus, getting tested, getting care, or general public following of pandemic restrictions and rules) and brand tone preference. Similarly, financial issues, while moderately concerning for this sample, did not associate with brand tone preference, except that people who preferred a comforting tone had comparatively lower scores on fear of losing money, e.g., on bookings or non-reimbursable purchases. There was a significant inverse association among various family/personal concerns in that people preferring a comforting tone expressed the slightest concern with family, children, or personal alcohol/weight issues.

Next, we summarize the results of the first three research propositions in table 3. R1 stated that stress would not significantly affect preferences for an informative brand tone. This was supported, as none of the 16 stressors were statistically higher or lower for consumers who preferred an informative brand tone. R2 posited that pandemic-induced stress would positively affect preferences for comforting, inspiring, and trustworthy brand tones. This claim was not supported. Consumers who preferred a comforting brand were significantly less worried about losing money, juggling family/work, schooling issues, other family issues, alcohol consumption, and weight issues. Moreover, there was no statistical association between stress and liking an inspiring or trustworthy brand tone. R3 postulated that pandemic-induced stress would negatively affect preferences for humorous brand tones. This was partially confirmed. Consumers who gravitated towards a humorous tone were significantly less concerned about COVID-19 in general, the American economy, and juggling family/work.

Coping strategies and brand tone preference

Inspecting the role of coping implied in R4, we captured data (table 3) on respondents' primary use of the stimulus funds received from the U.S. Government. While all brand tone subgroups applied the stimulus check mainly to essential purchases, people preferring a comforting tone tended to have the highest percentage of nonessential use of the stimulus, combined with a greater percentage of individuals who were not eligible to receive the check due to earning too much money. In comparison, those seeking an inspiring tone tended to use the stimulus more for essential purchases than the other brand tone subgroups did.

Table 3 Comparison of top choice use of stimulus check.

| Top choice use of stimulus check | Sample (n = 546) | Informative (n = 175) | Comforting (n = 115) | Trustworthy (n = 100) | Inspiring (n = 79) | Humorous (n = 77) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rent or mortgage | 36.4% | 40.0% | 35.7% | 31.0% | 38.0% | 35.1% |

| Make loan payments | 13.7% | 15.4% | 12.2% | 14.0% | 11.4% | 14.3% |

| Food and supplies | 11.0% | 10.3% | 13.0% | 13.0% | 12.7% | 5.2% |

| Other monthly bills | 10.8% | 8.6% | 10.4% | 11.2% | 10.1% | 16.9% |

| Transportation costs | 10.1% | 8.6% | 3.5% | 15.0% | 12.7% | 14.3% |

| COVID-19 supplies | 1.7% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 1.0% | 2.5% | 0.0% |

| Medical expenses | 0.9% | 0.6% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% |

| Prescription drugs | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 2.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% |

| Essential expenditures | 85.3% | 85.2% | 79.1% | 87.2% | 90.0% | 85.8% |

| Save for future use | 5.1% | 4.6% | 9.6% | 5.0% | 2.5% | 2.6% |

| Invest the money | 2.0% | 2.9% | 1.7% | 1.0% | 2.5% | 1.3% |

| Gift the money | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% |

| New personal items | 0.7% | 2.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| New home items | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% |

| Buy luxury items | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.3% |

| Pay for future travel | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Nonessential uses | 9.3% | 10.4% | 12.2% | 8.0% | 6.3% | 7.8% |

| Did not qualify for the stimulus check | 4.9% | 4.6% | 7.8% | 5.0% | 3.8% | 2.6% |

Source: authors.

Further investigation pertinent to R5 examined the outlets for relaxation identified by participants in this study (table 4). Many forms of relaxation, including videos, music, news, shopping, and exercise, are used by people in this study and show little discrimination across brand tone groups. However, people who want comforting tones spend the least time on more active or home-centered relaxation methods involving pets, voice interaction with smart home devices, gardening, home projects, travel planning, and sports.

Table 4 Comparison of relaxation methods across brand tone subgroups.

| Method | Sample (n = 546) | Informative (n = 175) | Comforting (n = 115) | Trustworthy (n = 100) | Inspiring (n = 79) | Humorous (n = 77) | Chi-square tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Videos/Tv | 95.2% | 96.0% | 95.7% | 96.0% | 94.9% | 92.2% | X2 = 1.970, 4, p = 0.741 |

| Music | 93.8% | 91.4% | 98.3% | 91.0% | 96.2% | 93.5% | X2 = 7.739, 4, p = 0.102 |

| Shopping | 90.7% | 91.4% | 89.6% | 91.0% | 91.1% | 89.6% | X2 = 0.403, 4, p = 0.982 |

| News | 90.3% | 89.1% | 84.3% | 95.0% | 94.9% | 90.9% | X2 = 9.312, 4, p = 0.054 |

| Exercise | 85.3% | 82.3% | 87.0% | 86.0% | 88.6% | 85.7% | X2 = 2.311, 4, p = 0.679 |

| Projects | 76.7% | 73.7% | 72.2% | 86.0% | 81.0% | 74.0% | X2 = 8.493, 4, p = 0.075 |

| Garden | 75.8% | 73.7% | 67.0% | 83.0% | 81.0% | 79.2% | X2 = 9.812, 4, p = 0.044 |

| Pets | 75.3% | 76.0% | 63.5% | 86.0% | 77.2% | 75.3% | X2 = 14.988, 4, p = 0.005 |

| Voice | 74.4% | 70.4% | 67.0% | 83.8% | 82.3% | 72.7% | X2 = 12.060, 4, p = 0.017 |

| Gaming | 71.8% | 72.0% | 67.8% | 75.0% | 77.2% | 67.5% | X2 = 3.242, 4, p = 0.518 |

| Travel | 64.1% | 63.8% | 48.7% | 71.4% | 65.8% | 75.3% | X2 = 18.418, 4, p < 0.001 |

| Meditation | 63.9% | 61.1% | 60.9% | 63.0% | 67.5% | 72.2% | X2 = 3.766, 4, p = 0.439 |

| Beauty/spa | 56.0% | 49.4% | 43.0% | 71.0% | 66.7% | 58.4% | X2 = 23.781, 4, p < 0.001 |

| Sport | 54.8% | 53.2% | 39.5% | 68.0% | 60.3% | 55.8% | X2 = 18.944, 4, p < 0.001 |

Source: authors.

Demographic influences

Of the various demographics assessed in exploring R6 (gender, age, marital status, race, income, education, and occupation), only gender and marital status showed significant associations with brand tone preference (table 5). Both genders wanted an informative style; however, a comparatively higher percentage of men wanted an inspiring tone, while a higher percentage of women wanted comforting. Regarding marital status subgroups, all three wanted an informative tone. More married respondents wanted inspiring and trustworthy, and more singles wanted comforting. Single other (divorced, widowed, and separated) also showed an interest in a humorous tone.

Table 5 Brand tone preference by gender and marital status.

*Chi-square = 11.320; df = 4; p = 0.023; **Chi-square = 21.414; df = 8; p = 0.006.

Source: authors.

Discussion

Many factors influence the perceived appropriateness of a tone used to represent a brand in its marketplace. In this study, the pandemic was classified as a global life stressor that could affect the brand tone preferences of consumers. Five brand tone types were evaluated as viable brand message options during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic: informative, comforting, trustworthy, inspiring, and humorous. Factors such as pandemic stress concerns, coping strategies, and demographics were believed to associate with the selection of specific brand tones, as depicted in figure 1. The results of this study will next be examined to align findings with existing theory.

Factors influencing brand tone preference

Informative brand tone

Information giving is a primary purpose of brand communications (Algharabat et al., 2020). The prominence of an informative brand tone is found across all marketing channels, including social media (Barger et al., 2016), radio (Janssens & Pelsmacker, 2005), and television (Ferraro & Avery, 2000). According to the marketing literature, informative messaging is a critical resource for consumers engaging with product and service companies. De Keyzer et al. (2017) found that a factual tone best conveys information about a service provider. This tone is preferred by consumers during the awareness phase when they are seeking brand information (Colicev et al., 2019). Based on the extant literature, we expected information to be a vital component of consumer searches during crises such as the pandemic. This was borne out by our study. The desire for an informative brand tone was the dominant brand tone in this sample, which 32% of respondents preferred. It proved to have no statistical association with levels of global or personal stressor concerns arising from the pandemic. Preferring an informative brand tone also had no apparent association with the demographics collected from surveyed individuals.

Comforting brand tone

The second most chosen brand tone was a comforting tone, selected by 21 percent of the sample. Preference for a comforting tone showed no interaction with overall stress about COVID-19 or the U.S. economy at the time. We see diverse results regarding personal concerns revolving around health, finance, and family/self-issues. Many items related to experienced health and financial issues during the pandemic had no association with choosing a comforting brand tone preference. However, preference for a comforting tone did have an inverse relationship with fear of losing money and various family personal concerns, including managing children's needs and personal alcohol/ weight issues. This suggests that wanting a comforting tone from consumer brands derives from something other than a desire to reduce personal or family stress. This is further confirmed in that people preferring a comforting tone expressed little need for the stimulus check provided by the federal government. Lastly, people who preferred a comforting tone spent the least time on relaxation methods. According to the alternative literature on stress, it is conceivable that factors not studied were driving the need for comfort messaging, i.e., fear or depressive symptoms of respondents might have more impact on brand tone preference than stress levels. To this point, Di Crosta et al. (2021) found that fear in their model completely nullified any effects of stress on pandemic buying behavior. They also noted the tendency for people with higher levels of depressive symptoms to pursue nonessential purchases to enjoy hedonic benefits that might uplift their negative emotional states.

Notably, it was evident that gender mattered in preferences for a comforting tone. More women (25.9%) than men (16.0%) preferred a comforting tone. There was also an interaction with marital status in that both single (never married) and single (divorced, widowed, separated) showed a greater propensity to select a comforting tone than married individuals. These results suggest that a comforting tone from brands may fill a gap in the social lives of single and female respondents, as suggested by the literature on social ties. Social networks vary by gender as men develop social relationships at work, and women form more informal and private relationships (Kim et al, 2020). Women tend to have more extensive social networks (Dykstra & Fokkema, 2007); however, this wider social network can lead to strain as they cope with supporting more people (Santini et al, 2016).

Trustworthy brand tone

A trustworthy brand tone was the third most commonly selected option (18.3%). There was no association between wanting a trustworthy tone and any of the overall or personal concerns about the pandemic. People selecting a trustworthy tone did not reveal any unorthodox uses of the stimulus check or relaxation tactics. It is possible that, like public agencies, commercial brands are not viewed as the most reliable creators of solutions to pandemic stress. This perspective is suggested by Varón-Sandoval et al. (2020), where public agencies generated the opposite of trust and positive emotions, while social networks formed among members of the general population were deemed more trustworthy.

Slightly more men (19.7%) selected a trustworthy tone preference than women (16.3%). Of note, a monotonic decrease was noted across marital status types, with married (22.2%), single never married (13.5%), and single other (7.0%). This matches previous findings about married couples, i.e., married people take fewer risks than single people (Fagundes et al, 2011). On the consumer side, married consumers were less likely to purchase online than single consumers (Bhat et al., 2021). This highlights the possibility that, for married consumers, trustworthy messages suit their cautious natures.

Inspiring brand tone

The fourth most selected brand tone is an inspiring tone (14.4%). As with the informative and trustworthy brand tones we see no significant associations between wanting an inspiring brand tone, and the level of concern people had with COVID-19. However, people preferring an inspiring brand tone reported the highest use of their stimulus checks on essential as opposed to non-essential items.

Previous studies investigated the impact of inspirational messages. Brand messages can inspire consumers during the shopping process (Tang & Tsang, 2020). Brand videos with an inspiring message have a positive and persuasive impact on consumers (Chang, 2020). Our findings on inspirational messaging contribute to a longstanding debate about whether "people struggling to meet their basic needs...have the 'luxury' of caring about intangible values" (Satz et al, 2013, p. 680). We found that comparatively more men (17.5%) than women (11.5%) selected the inspirational brand tone. Married individuals (16.7%) also selected an inspiring tone more often than singles (11.4%). Male and married respondents have been reported to have greater stability during the pandemic than female and single individuals, suggesting inspiration could be a non-essential luxury item. However, our study also found that people selecting inspirational messaging had the highest application of stimulus funds on essential needs rather than on non-essential purchases. This topic of inspirational focus being a luxury item for society is indeed an intriguing concept worthy of further investigation.

Humorous brand tone

Preference for a humorous brand tone (14.1%%) was slightly below the inspiring tone. Interestingly, a preference for a humorous tone coincided with statistically lower overall concern about COVID-19 and the U.S. economy. No statistical relationships existed between humor and most personal concern items or relaxation tactics. However, this study shows a unique association with marital status in that 'other singles,' i.e., divorced, widowed, and separated individuals, reported a significantly higher interest in a humorous brand tone. A preference for humorous brand tones may signal a personal trait or cognitive processing style that was not studied in our research. Stigel (2011) suggested that humor shifts the original referent point of communication to another field, implying that people who liked a humorous brand tone in our study may be seeking some escape from their current situation.

Practical implications

Marketers traditionally have engaged consumers through brand communications that engender emotions of enjoyment and enthusiasm in their customers (Brodie et al., 2013). Alternatively, extraordinary circumstances like the pandemic call for novel approaches using brand tone to achieve desired effects on customers. In their study of COVID-19 brand messages, Mensa and Vargas-Bianchi (2020) noted positive and nurturing messages added to existing messages of excitement and nostalgia. One logical avenue would be to align tone with projected consumer stress levels during the COVID-19 episode. Nagpal and Gupta (2022) reported significant impacts of brand communication on consumer perceptions during the pandemic; however, not all these messages elicited a positive response. While Internet information was desired by consumers, it increased health-related stress of consumers (Farooq et al., 2020). Stress levels rose due to inaccurate information circulating on social media channels.

Brands have struggled to manage communication strategies during the pandemic because they must identify appropriate tones and create tailored messages for different stakeholders (Ma et al., 2019). One study suggested that brands should use an empathic tone during this stressful time (Hesse et al., 2021). We find that suggestion too limiting as a strategy. Our research focused mainly on the relationships among perceived pandemic stressors, coping strategies, and common demographics. It was clear from our results that multiple brand tones are necessary to satisfy the needs of diverse consumers. The tone used by a brand can influence a consumer decision (Barcelos et al., 2019). Several studies noted that a positive message elicited a positive consumer reaction (Nam et al., 2020; Purnawirawan et al., 2015). Other studies found a positive correlation between a conversational brand tone and consumer engagement (Barcelos et al, 2018; Park & Cameron, 2014; Sung & Kim, 2021). However, an informal tone increases trust with consumers who know the brand but has the opposite impact on consumers who are unfamiliar with the brand (Gretry et al., 2017).

This study has important managerial implications for brands communicating with consumers during stressful situations. Consumers want informative messages during uncertain times just as much as during non-crisis periods. Clear and timely information is good marketing practice regardless of being in a pandemic or not. However, brand managers should consider using other brand tones to connect with consumers and can take advantage of studies like this to understand who, in particular, might be receptive to other brand tones and why. Based on our findings regarding gender and marital status, female consumers could benefit from a strategy of mixed tones yielding both information and comfort to feel socially connected to others during the pandemic. This includes verbal messages and the strategic selection of images to promote the sense of being in a relationship with the brand, its employees, and even co-consumers. Men seem to be open to inspiring messages and ones that convey trustworthiness.

A little bit of humor is thought to help relieve emotional stress. Still, humor may distract customers, so its placement might be better after the main information has been presented to viewers. We saw no evidence that humor by itself was a broadly accepted brand tone, being that only single others (divorced, widowed, and separated) had significant interest in it. The fact that people who preferred humorous messages were also the least concerned with overall COVID-19 and the economy suggests that there may be an unknown social or psychological division between consumers prompting liking or disinterest in humor. If only a portion of a company's audience is humor-oriented, prioritizing more informative or trustworthy messages is the safer communication strategy for brands.

Conclusions

This study filled a gap by investigating preferred brand tones during a crisis. Brands craft their messages to communicate with customers, and a single communication style may not resonate with consumers due to the brand tone used. This research found that consumers opt into diverse brand tones, suggesting that companies may be making a mistake by creating communications focusing on a single tone. A humorous message may be dismissed by consumers seeking information in a stressful environment filled with negative news and pandemic updates.

Furthermore, brand tone preference was only partially explained by the stress factors examined in this study, and any significant relationships were inverted rather than positive associations. This suggests that, in the main, other unknown factors were more important than perceived stress in dictating brand tone preferences in this study. However, there are some worthwhile considerations, particularly regarding preferences for a comforting and humorous brand tone. Our results showed a consistent pattern where comfort was chosen by people with lower levels of concern about the impact of COVID-19 and lower use of relaxation tactics. If the need for comfort is not generated by stress, what exactly defines it in the minds of these respondents? We suggest that people selecting a comforting tone want social inclusion or networking rather than a stress remedy. Alternatively, factors such as depression or personal traits might better explain nurturing brand tone choices.

Demographics do matter in consideration of brand tone preference. Gender and marital status showed significant associations with the different brand tones. Regardless of marital status, both genders preferred an informative brand tone during the COVID-19 lockdown. More women than men gravitated towards a comforting tone. More married respondents wanted trustworthiness, and more singles wanted comfort. Single other (divorced, widowed, and separated) also showed an interest in a humorous tone. Our work also suggests that males and married couples are more accepting of inspirational messaging, which tends to be more cerebral and less focused on offering immediate solutions to pandemic struggles.

Limitations and future research

The first limitation is the issue of tone and business sector fit. It may be that brand tone styles will vary across product categories. Entertainment venues, for example, will not usually convey the same tones as funeral homes. While insurance firms might adopt a stance to comfort or reassure their patrons using trusted celebrity spokespersons, many insurance company ads exhibit humor. Quite possibly firms want to disassociate their brand image from the emotionally draining accidents that are the basis for insurance payouts.

The second limitation is that the study is U.S.-based, without extensive capture of cultural background information. Future studies could benefit from exploring the literature on stress management and communication styles to incorporate more awareness of cultural differences. Comparing responses across different countries could reveal if different cultures emphasize different brand tones even while selling the same product, for example, automobiles or insurance policies. Companies also have begun to create platforms that encourage consumers to share co-production of branded content, including pictures and videos (Carvalho & Fernandes, 2018) that could be an additional cultural element, i.e., looking at tones from co-consumers.

A third limitation is that self-reported perceived stress was measured as opposed to physical or body measurements of stress. Since we were accessing consumer data from a secondary source, it was impossible to do anything more aggressive. As a future research idea, people could be studied using experimental methods by capturing physical stress levels when introduced to different types of stressful scenarios and measuring physical and emotional reactions to brand message examples using a variety of tones.