Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Estudios Políticos

Print version ISSN 0121-5167On-line version ISSN 2462-8433

Estud. Polit. no.38 Medellín Jan./June 2011

Understanding the contemporary United States and European Union foreign policy in the Middle East*

Entendiendo la política exterior de Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea en el Medio Oriente

Necati Anaz**

** BA. Political Science, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey; MBA Management, Wilmington University, Daleware, USA; MBA Public Administration, Wilmington University, Daleware, USA; PhD. (Candidate) Political Geography, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma, USA. E-mail: anaz@ou.edu.

The author would like to acknowledge the immensely helpful comments and valuable insights of the anonymous reviewers. He would also like to thank to Mehmet Ozkan, Matthew R. McNair and Yusuf Karacaoglu for their kind support and encouragement. Any remaining shortcomings are the author’s own.

ABSTRACT

United States, as the dominant geopolitical power in the Middle East, has been struggling to stabilize the region to achieve its geopolitical objectives and interests. Especially since the Second World War, the US has rioritized, enacted and represented Middle East policies as vital to securing its "national interests" till terrorist attacks on the twin towers in New York City. As it is understood, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, markeda dramatic changenot onlyin US policy, but in USrhetoricandinternational discourses as well. Following the terror attacks, US Middle East policy shifted from being the matter of "national security," which primarily puts more emphases on "responsive securitization", to the "preventive securitization of national interests," particularly under the neo-conservative Bush Administrations. Consequently, US launched two direct military engagements in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003), and involved in unilateral regime change in those states ostensibly, to secure its national interests and provide world peace in the long run. It is important to highlight here that US cleared the full support (rhetorically, at least) of the United Nations to disarm the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. This study, therefore, attempts to revisit and conceptualize the contemporary US and EU Middle East foreign policy though they are not identical before and after the September 11 terror attack. The argument here is that the Middle East policy objectives of the US and the EU primarily agglomerate around two main headings: security of oil and protecting the state of Israel in an Arab-dominated region. Closely related, but not equivalent, both the US and EU have a stake in establishing good relations with the Arab states and promoting democracy and liberal market economies in the Middle East. This study also reviews the President Barack Obamas Middle Eastern foreign policy initiatives and attempts to suggest several key points.

Keywords: US and EU Foreign Policy; Middle East; 9/11; 2001; Security; Obama Administration.

RESUMEN

Los Estados Unidos, como el poder geopolítico dominante en el Medio Oriente, han estado luchando por estabilizar la región con el fin de alcanzar sus objetivos políticos y lograr sus intereses. Particularmente desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Estados Unidos ha priorizado, instituido y considerado las políticas del Medio Oriente como vitales para asegurar sus "intereses nacionales" hasta los ataques terroristas a las torres gemelas en la ciudad de Nueva York. Como es claro, los ataques terroristas del 11 de septiembre de 2001 marcaron un cambio dramático, no solo en las políticas de Estados Unidos, sino también en la retórica estadounidense, así como en los discursos internacionales. Luego de los ataques terroristas, las políticas de Estados Unidos con relación al Medio Oriente pasaron de ser una cuestión de "seguridad nacional", lo cual básicamente hacía más énfasis en "la seguridad defensiva", a ser una cuestión de "seguridad preventiva de los intereses nacionales" principalmente bajo la administración neoconservadora de George W. Bush. Como consecuencia, Estados Unidos adelantó dos incursiones militares en Afganistán (2001) y en Iraq (2003) donde se puso en la tarea de cambiar unilateralmente y de manera sensible el régimen de dichos Estados con el objeto de asegurar sus intereses nacionales y procurar la paz mundial a largo plazo. Es importante resaltar aquí que Estados Unidos autorizó el completo apoyo (por lo menos retóricamente) a las Naciones Unidas para desarmar el régimen Talibán en Afganistán. Este estudio revisa y conceptualiza la política exterior actual de los Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea con respecto al Medio Oriente aunque no son idénticas antes y después de los ataques terroristas del 11 de septiembre. El argumento aquí presentado es que los objetivos de la política exterior con relación al Medio Oriente, tanto de los Estados Unidos como de la Unión Europea, giran principalmente alrededor de dos puntos: la seguridad del petróleo y la protección del Estado de Israel en una región predominantemente árabe. De manera similar, aunque no exactamente de la misma forma, tanto Estados Unidos como la Unión Europea tienen intereses en establecer buenas relaciones con los Estados árabes así como en promover la democracia y la economía del mercado libre en el Medio Oriente. Este estudio también revisa las iniciativas de política exterior con el Medio Oriente del presidente Barack Obama e intenta indicar algunos puntos clave.

Palabras clave: política exterior de Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea; Medio Oriente; 9/11; seguridad, administración del presidente Obama.

Introduction

Writing on the USs Middle East policies is as challenging and complex as the issues themselves. The intractable nature of talking about USs Middle East policies comes from writers and commentators polarized and personalized inclinations toward the issues, and this paper is not immune to these tendencies. Belying voluminous writings and innumerable talks concerning the subject, in its simplest form US Middle East policy can be grounded in two primary objectives: securing Americas lifeline oil reserves, and maintaining the physical and political integrity of the Jewish state (See Watkins, 1997). These two main objectives of the US have given rise to vehement political moments and movements invariably in protest of those objectives, in particular, and of the US, generally in the Middle East from Israels inception. On the one hand, the US needs to deal with uncooperative and unreliable Middle Eastern regimes while prioritizing the security of Israel and its interests in the region. On the other hand, the US wants to ensure the steady flow of oil from totalitarian Arabian regimes, even as it advocates changes in their political systems and supports only pro-Western movements in the Middle East. These self-assigned geopolitical objectives from time to time force US to pursue contradictory and paradoxical policies in the Greater Middle East. In other words, the ideal US Middle East policy is shaped around geopolitical realism that is intricately tied to neo-conservative idealism.

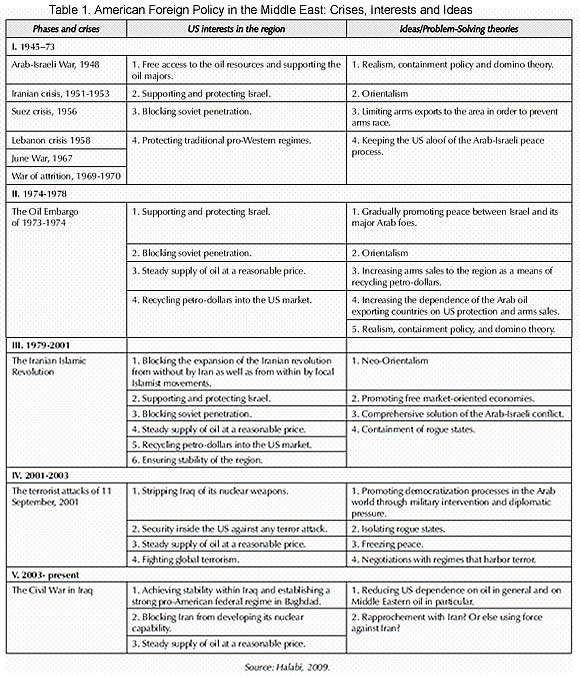

This study, thus, aims to revisit the last fifty years of American and European Middle East policies and attempts to analyze the resultant political dilemmas of these policies and their implications. To do this, Yakub Halabis Middle East crisis analysis schema will be used as the road map. Of course, his categorizations are not complete, nor do his categories constitute the last word on the subject, but they compose the most useful and inclusive explanations at the moment. This paper will also briefly try to sketch the similarities and differences in EU and US Middle East policies before and after the 9/11 terror attacks.

1. Contextualizing US Policy in the Middle East

US relations with the Middle East have been inconsistent and problematic since the reconstruction of the Jewish state, literally, in the Arabian land and the discovery of middle Eastern oil, which became a lifeline of the US economy (See Halabi, 2009 and Watkins, 1997). It is inconsistent because US objectives in the region have always fluctuated depending on the geopolitical conditions of ongoing events and political developments. During the Cold War, for instance, the US strongly supported the regime of the Shah in Iran versus the popularly elected Iranian government; this indicated that the US preferred seeing a corrupted but loyal totalitarian regime in Iran. US foreign policy in the Middle East is also problematic owing to the fact that, after the Second World War, US policies in the Middle East turned into the conflict management between Israelis, Palestinians, Arab states, Western countries, regional petroleum sheiks, and oil-importing non-democratic states.

Halabi, in his book US Foreign Policy in the Middle East, charts US-Middle East relations in five phases. These phases are neither mutually exclusive nor mutually inclusive, but are distinct and interrelated, and prone to overlap; therefore, the five different categorizations are, for convenience and clarity, reorganized into four groups in this paper (See table 1). He explains each phase as nodes of crises, and optimal policy managements for those crises. For instance, the first phase constitutes US interests and ideas in and of the Middle East that stretch from the Second World War to the 1973 the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil crisis. During this period, US interests mainly included protecting the young state of Israel at the expense of Palestinians, securing oil exportation and concomitantly ensuring oil-rich, pro-western family-operated regimes remained in control of the oil reserves and the exportation of same. This allowed not only for the pragmatic and necessary supply of oil to US markets, but also served to achieve the ideological and military goal of keeping Communist Russia away from major oil fields, impressionable populations, and strategicallyvaluable territory. Policies of this time put strong emphasis on containment strategy and the so-called domino theory, while simultaneously conducting an ideological "othering" of the Middle East the much-ballyhooed "clash of civilizations" via all kinds of media (See Dittmer, 2010a and Said, 1997).[1] In the second phase, which constitutes the period of the oil embargo (1974-1977), US foreign policy makers focused on a steady flow of cheap Arabian oil to the United States; meanwhile, they attempted to ensure that Middle Eastern states, especially geo-strategically important countries, did not fall under the influence of communist Russia and, further, that those oil rich Arab states did not gain excessive military power, military power that could seriously endanger the state of Israel and other US allies in the region. Thus, the US spent quite a large amount of time and effort to guarantee the oil patrons petrodollars were inserted back into the US market, and that those petrol dollars were not used to purchase heavy arms that might go for supporting and benefiting anti-west radical organizations. The US government, therefore, pursued a policy that aimed to keep OPEC states (dysfunctional, uncooperative states if necessary) under control, all the while pushing the Israel-Arab peace process.

In the third phase, the Iranian Islamic Revolution will be the turning point where US-Middle East relations escalate to another level. This third phase stretchesfrom1979toal-QaidasattackontheUSin2001.TheIslamicRevolution in Iran and the following hostage crisis changed the course of US Middle East foreign policy fundamentally, if not completely. Since then, the US has backed Israels preemptive strikes on dissident regional Islamic movements, and such support became an important policy component for the US, and carried serious geopolitical implications. Priority was given to the containment of radical Islam and the possibility for the dangerous merging of oil-rich radical nationalist regimes of the Middle East with Communist Russia. Thus, the US worked hard to assure that the Middle East embraced Western cultural values as well as the liberal market system as an alternative to Communism and radical Islam. Both radical Islam and Communism are perceived as dangerous to the Western-imposed new world system (See Ozkan, 2007).

The fourth phase begins with the terrorist attack on September 11th of 2001, and continues to the present day. In this new chapter of US foreign policy, the Middle East occupies a significant amount of space, both figurative and literal. US objectives in this phase entail "preemptive prevention" rather than focusing on self-defense, for example, protecting the mainland of the United States from possible intercontinental missile attacks or engaging in a regional crisis management overseas (See Fukuyama, 2004). In other words, the concept of geopolitics has shifted to be understood as administration of the globe since the attack of September the 11th on US cities (See Dalby, 2009). As a consequence of that, the geopolitical concept of danger has changed and become more global. And the American soil, as witnessed on 9/11, was believed to be no longer immune to deadly attacks from the outside. This was the first time when Americans saw, smelled, and touched the total destruction of two symbolic landmarks in the heart of their homeland.

In this context, this paper coordinates the discussions of the USs and, to a lesser degree, Europes, objectives in the Middle East from multiple dimensions, including energy security, protecting Israel, securing the homeland, democratization of the Middle East, and establishing a neoliberal world order. In other words, the US objectives after 9/11 meant more than just a simple military struggle (securitization) for the neo-conservative Bush administration.[2] They meant that US objectives were eternal and universal in their essence, and to struggle to keep these universal values of humanity alive and functional in the 21st century and onward was a sacred struggle as well as a vital responsibility of the worlds lone superpower. Concomitant to this reification and acceleration of exceptionalist foreign policy, a neoconservative think-tank, Princeton Project, itemizes US National Security objectives in the 21st century as securing the homeland against hostile attacks, building a healthy global economy, and spreading liberal democracy (See Parmar, 2009).

1.1 Securing Oil

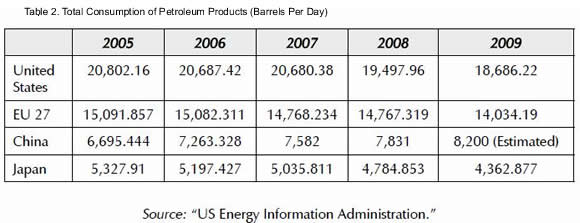

As the global demand for oil increased, US Middle East policy became more militaristic and aggressive than ever. Due to the fact that oil reserves have been controlled by in the essence family-owned countries despotic and hostile regimes such as Saddams Iraq and the Saudi Kingdom, politics of providing undisrupted flow of oil into the US market has shifted from what is essentially known the "energy policy" to "national security policy" in the minds and rhetoric of American policy makers. For example, US former Deputy Secretary of Energy David Curtis acknowledged the concern of the US and Europe about how oil revenues are spent by the despotic regimes of the Middle East (See Watkins, 1997). The US worried that oil rich states would spend petroleum dollars for arm sales from the former Communist state, China (officially China is still a Communist state), whose oil consumption is estimated to be equal to that of the US in the near future (See table 2). For this reason, the US wants to make sure major oil-exporting countries such as Saudi Arabia continue to buy their military equipment and munitions from the US suppliers and remain allied with the United States. This policy, in turn, will challenge US democratization attempts in the Greater Middle East.

Table 1. American Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Crises, Interests and Ideas

Table 2. Total Consumption of Petroleum Products (Barrels Per Day)

1.2 Israeli Exceptionalism

Since the establishment of Israel, US foreign policy in the Middle East has been more problematic than before. As the US worked hard to keep oilrich, radical Arabian states from falling under the Communist influence, the US also pushed liberal ideas toward the region while struggling to find a fine line, politically, between securing the Middle East oil and protecting Israels interests in the middle of Arabian land (See Crosston, 2009 and Halabi, 2009).

After the collapse of Communism in 1989, the USs main geopolitical concern became containment of Islamic extremism, as these radical formations could ultimately become the primary roadblock to the easy flow of oil and become a serious threat for the security of the most important US ally, Israel, in the region. In reaction to the emerging power of popular Islamic realism (especially after the Iranian Revolution, which made people believe a rapid establishment of an Islamic state possible) among young people whose economical demands are unsatisfied but hopes and dreams are captivated by radical Islamist oppositions, US unsurprisingly reproached and supported Israels politics in the region as well as dedicated itself as the sole representative of Israel in critical international forms. In this sense, the USs loud and clear pro-Israel stance during the Arab-Israel peace process and related territorial issues became the subject of heavy criticism by many. The USs support for Israel has always been unconditional and disputable, and this kind of political attitude resulted in two contradicting and, therefore, never-ending conflictive policies in the Middle East for the United States. First, in order to continue importation of Arabian oil and to suppress anti-Israel sentiments in the region, the US obliged itself to pursue a policy that would necessitate holding pro-Western Arab leaders/rulers in power despite the mass of dissident voices from within oppressed and economically disadvantaged populations. Both overtly and tacitly, US provided financial and military supports to Arab leaders who would use any means necessary to oppress their public and maintain their absolute power over the people. This approach brought two understandable consequences for the US, particularly, and the West, in general. First, democracy did not find a sustainable environment to grow, and, second, this ill-managed policy provided healthy conditions for the growth of extremism (if the Iranian revolution is counted to sow the seed of extremism) in the Middle East. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Islamic Community in Pakistan, and Osama bin Ladens al-Qaida are among those organizations in which dissident and desperate young populations found a place to openly and effectively fight against American efforts in the Middle East these organizations, of course, are not the same in their tactics, strategies and organizational structures in the fight against an American-dominated world order in the Middle East, and, thus, they should not be over-generalized as terrorist organizations.

Secondly, the USs unconditional support for Israel fed a common belief in the Middle East that the US would never be a neutral mediator when political issues relate to Muslim people, their values, and lifestyle. This cynical attitude toward US efforts justifies the idea that everything is a part of a Judea-Christian project that targets the very existence of Islam and the Islamic lifestyle in the Middle East and elsewhere. Continuing Israels occupation of Palestinian territories, military campaigns against Hezbollah and Syria, and USs preemptive interventions in the Muslim world, while showing reluctance to regulate Israels aggressive actions in the region, only enforced this cynical belief in the eyes of the Muslim people.

Another important reason why US cannot become an impartial and effective mediator in the mind of the Muslim world concerning the peace efforts in the Middle East is the existence of a tremendously influential Jewish constituency in every sector of commerce and branch of government in the United States. For example, the recent neo-conservative Bush Administrations diplomatic support of Israel in the United Nations, and overwhelming bipartisan majority voice of support resolution in the US Congress with regard to Israels war on Lebanon demonstrate that the US is not even close to being a neutral mediator in the Arab-Israel relations, and certainly is not a seeker of ultimate peace in the region. Furthermore, according to the Jerusalem Post, the Bush Administration did not only support the Israeli attack on Lebanon in 2006, but the administration also urged Israeli military leaders to expand the war beyond Lebanon (See Zunes, 2009). Zunes quotes Lobe and adds that "in the early days of the fighting, US Deputy National Security Adviser Elliot Abrams reportedly met with a very senior Israeli official to underscore Washingtons support for extending the war to Syria" (Zunes, 2009, p. 583). This unconditional support for Israel is not a secret to anyone anymore. In turn, Israeli exceptionalism in the region ultimately undermines possible peace in the region and prosperity for the innocent majority.

1.3. Ideological Warfare and Democratization in the Middle East

Scholars from many disciplines have long been skeptical about the actual differences between US imperialism and the European brand of it. In the political history literature, it is thought that US imperialism has never engaged in firsthand military administration or direct exploitation of human and natural recourses of the occupied territories. However, this argument has been questioned many times and brought to an end soon after US opened two fronts against global terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq. US directly and unilaterally invaded two internationally recognized countries to end the so-called radical Islamic terrorism before it finds solid conditions to reemerge.[3] This preemptive prevention war in Afghanistan and Iraq has been shifted to an ideological war of neo-conservatism. The plan was simple. The routed regimes of the Taliban and Saddam Hussein were going to be disabled and, then, the conditions for a solid democracy would be created.[4] Moreover, this regime change was going to be justified for the sake of peace in the Middle East and the world. The Bush Administrations aggressive democratization in the Middle East aimed to hide the real agenda of controlling geostrategic territories in the Middle East and expand the borderlines of American national security overseas (See Crosston, 2009). In other words, the Bush Administration aimed to operate Wilsonian ideology as a real-world policy (See Crosston, 2009). Remarkably, under the Bush Administration US objectives principally highlighted three main doctrines: assist, advocate or force, if necessary, democratic principles and developments in the Middle East, establish a market economy and free entrepreneurship, and create a free-zone bereft of weapons of mass destruction in the region Israels nuclear capability considered exceptional although Israel has neither confirmed nor denied their existence. These objectives were understood to be the only vital elements for a peaceful Greater Middle East. However, US democratic premises for the Middle East were ill-formed, because the very first principle of democracy denies any aggressive democratization. People must have free will to choose what sort of government they wish to have. Beside all this, the US has never been consistent with its understanding of democracy and interpretations of same. The international community has many times witnessed that the US is not accepting of any grassroots organizations in the Middle East that openly criticize the United States foreign policies. After Hamas collected the majority of the popular vote in Palestinian parliamentary election in January 2006, the US, along with Israel, refused to have any kind of diplomatic relations, and showed minimal respect to the Palestinian peoples democratic choice. Not surprisingly, the US denies the legitimacy of the popularly-elected and -accepted Hezbollah, and declares it as a terrorist organization, while it shows full support for the totalitarian regime of the oil-exporting country of Saudi Arabia, a country ruled by a regime which is well known to be one of the worst violators of human rights in the world. This is not even to mention the fact that the majority of 9/11 hijackers carried Saudi citizenship. The USs inconsistent and contradictory policies in the Middle East made people of the region and other communities of the world become skeptical about the overall democratization efforts and leadership of the US in the post-9/11 world order.

2. Europe and the Middle East: Search for a Strategy

Europes (the EU 27) Middle East policy is not less problematic and complicated than that of the US, especially after the September 11th terror event. This complication should be examined within Europes unique geopolitical position (See Lewis, 2009). While Europe shares some common geo-economic qualifications and universal values with the United States, such as promoting liberal democracy and the rule of law in the Greater Middle East, it also hosts millions of Muslim people (15% of total population) from all over the world, and shares geographical and cultural proximity to the Northern African Muslim states in its Eastern and Southern flanks. If the ongoing enlargement negotiation with a Muslim country, Turkey, is completed successfully, Europes physical borders will be stretched to all the way to Iran, Iraq and Syria (See Diez, 2004). This geopolitical reconditioning of Europe will force policy makers to maintain a balanced Middle East policy that rejects pursuing the aggressive one that American neo-conservatives would like to vision. This balanced Middle East policy, not surprisingly in the European context, necessitates Europe to stand for diplomatic solutions and multiparty negotiations, even though these political talks make no credible changes on the ground, as in the case of Israel-Palestinian and Bosnia-Herzegovina (See Anceschi, Camilleri, & Petito, 2009). This is not, however, to say that all European countries share the same attitudes about what should constitute Europes substantive long-term goal of promoting peace and stability in the Greater Middle East (See Anceschi, Camilleri, & Petito, 2009). For instance, Europe expectedly divided in three different approaches during the debate about whether the EU should join the aggressive call by the US to overthrow Saddam Husseins regime in Iraq. Political commentators agreed that Europe divided mainly in these broad positions in terms of reception for the American strategy of pursuing forceful regime change in Iraq: "Atlantisist (new Europe), Europeanist" (old Europe) and "no action at all group," the latter so-called because it believed that the Iraq war was Americas war and Europe needed to stay away from it. This disunity of Europe, to some commentators, mocked the geopolitical vision of the European Union (See Calleo, 2004). Europes impotent effort to form a unilateral, external political agenda deserves serious attention. The bilateral presence of individual European states in foreign policy limits the unions ability to become an influential political actor in the making of a world order. Alun Jones and Julian Clark explain this European dilemma in these words: "Europeanization is characterized by an ongoing internal tension and interplay between the drive to act collectively on the world stage and the desire by EU Member States to retain national autonomy over foreign policy goals and actions. Importantly, this tension is seen as a key explanatory factor in the apparent success or failure of the Europeanization process" (Jones & Clark, 2008, p. 546).

Europe desperately strives to diminish fractured voices with the union in order to fortify its foreign policy goals and objectives toward its near abroad, especially the south and the East. For this reason, Europe prioritized the stability and the security of its neighboring states. Alternatively, Europe pushed to increase economic, security, cultural and social relations with Mediterranean countries under the Barcelona Process. Can these European initiatives of being the regional actor succeed in peacemaking process in the Greater Middle East? This is the matter of political riddle of Europe. Israel, for instance, does not appreciate any European involvement in Palestinian issues, while Arab states give very limited credit to European effectiveness in the region. However, Iran and other regional actors want Europe to take more proactive positions to balance out US power in the Middle East.

European security is not bound only to the security of the heartland, but it is also bound to Euro-Maghreb trace balance that stretches from importation of Middle Eastern oil to arm sales and humanitarian aids. Very few European countries are self-efficient in terms of their energy dependency. Europe not only imports Middle East oil but also it purchases Northern African petroleum to comply with its energy needs. This energy dependency to Middle East along ties Europes both hands to pursue radical corrections on the ground regarding making peace in Palestine and elsewhere (See Matthes, 2004). Especially the small-economy countries in Europe will adapt pragmatist politics toward application of strong sanctions against brutal regimes and their inhuman politics toward civilian oppositions, because their dependency to imported energy recourses is more crucial than that of big-economy European states. For instance, Cypruss (Greek part of the island) more than 90% of energy need depends on transported energy. This geo-economic complexity of small states will ultimately affect their dissident stands against unpopular inquiry of Israel and the United States, as witnessed during the war on Iraq in 2003.

2. 1. European Complexities: Opportunities with(in) Challenges

What kind of opportunities and challenges face Europe in terms of the future of the Union and the Greater Middle East? Europe was found to be soft in mobilizing its military capacities in times of need and accused of not acting quick enough in the name of universal values and human rights. A striking example is the Bosnian genocide that occurred right in the backyard of the European heartland. Europe was so ineffective and slow to act that the result was the displacement and murder of millions of people by Serbian nationalists. Since the Bosnian War, Europes incapability of mobilizing its military power has brought serious doubts about Europes capability of contributing to the peace of the Greater Middle East. Unlike the US, Europe shows consistency with the United Nations Palestinian resolutions on their territorial claims and two-state solution; like the US, however, Europe exhibits reluctance to establish diplomatic relations with the popularly-elected Gaza administration and other dissident political movements in Palestine, as well as in other Middle Eastern regions. Europes attitude of denial toward recognizing Islamist currents in the region may jeopardize long term stabilizing peace within the Middle East and Europe. Europe, with its geographical and cultural proximity to the Islamic reality, can change the course of a possible "clash of civilizations" and may become the leading figure in bridging the Islamic question in the current geopolitical world order (See Kurth, 2006). Of course this brings us back to the question of "identity" and what constitutes "Europe." Europe eventually will have to establish "self-recognition" (what constitutes Europe) and a European collective position (a road map) in the post-9/11 geopolitical world order without contradicting the position of other leading actors (See Smith, 2009 and Sandole, 2009).

3. Europeanization of US Foreign Policy under the Obama Administration: What has Changed?

As the Obama presidency rolls over the second half of its first term in the White House, no credible change has been made pertaining to Middle East affairs; notwithstanding the preemptively (maybe preventively) presented Nobel Peace Prize to the president. Even though, Obama came to power with the promise of giving a greater chance to diplomacy and concrete improvements on the ground regarding the Israelis illegal settlements, the Gaza offensive and blockade of Palestinian ports even though all these issues departed during the Bush Administration, remain to be an acrimonious situation in Palestine. Despite the inherited aggressive foreign policy of the Bush administration toward the Middle East and third world nations, the hope of change and replacing the "cowboy diplomacy" with more respectful attitudes toward the sovereignty of the worlds independent states was discarded in favor of the status quo. Obamas promised changes stayed shallow and rhetorical. Obamas war, on the other hand, remained as open-ended and undefined as Bushs war. As he made clear in the speech he gave during the conference meeting announcing the replacement of General McChrystal with General David Petraeus, the change was not a change in policy, it was a change in personnel. He restated that US Afghan policy is more or less tied to a military solution. This is despite the fact that such a solution has long been proven ineffective and incompatible with the geography and dynamics of the region.

"We are going to break the Talibans momentum. We are going to build Afghan capacity. We are going to relentlessly apply pressure on al-Qaida and its leadership, strengthening the ability of both Afghanistan and Pakistan to do the same" ("Daily News," 2010, p.2). Obama not only disappointed his international audience, but also the people of the United States. People in the US and around the world kept hoping to see a more approachable and impartial American leadership under the Obama presidency. With Obama, the world communities anticipated to a US consistent with, and committed to, universal values and norms. In this way the US would become a much like a unified but better Europe, whose respect for diplomatic solutions and territorial integrity and emphasis on balanced positions regarding Arab-Israel issues, would aid in implementing international rules and regulations.

3.1 The Nuclear Test

The Iranian nuclear predicament, for the Obama administration, continues to be one of the most problematic aspects of his first term. Bushs "no choice but war or sanctions" policy toward Iran turned into "you choose either international isolation or possible air strikes." From this no-alternative solution package, Obama sided with the initiative that would enforce tougher economic, military, and political sanctions on Iran by convincing other permanent members of the UN to go along with this tougher strategy. The nuclear deal that Iran, Turkey, and Brazil made alternatively was dysfunctionalized by the United States. Thus, isolating Iran in every possible way from the rest of the world became the best of a set of bad political solutions for the US. But one should ask if this is such a rational solution to the issue. To the critical eye, the new resolution means that a more isolated Iran can pave the way for two possible outcomes: a) internationally-isolated Iran may look for any possible way out from the isolation, or b) (whether a war breaks out or not) ruling madrassa clergies and mainstream idealogues take advantage of the mayhem to increase their dominance on every aspect of Iranian social and political life. And parallel to that, an Iran isolated from the international community leaves plenty of room for an orthodox ruling elite to discourage, if not kill all altogether, emerging pro-Western and democratic voices in Iran.

Europe, in this matter, has not come up with alternative solutions to the Iranian nuclear crisis due to its lack of producing univocal Iranian politics. There are so many nations and national cards at stake which prevent Europe to produce suggestive and imposable politics. Europe seems to be reluctant following USbased solutions. Unless Europe actively engages in the policy making process, the US will never give up on pursuing aggressive policies toward the Iranian nuclear dilemma.

3.2 "Its the Eco-sociology Stupid"

One finds no reason why Obama favors keeping the status quo and making the same mistakes with which the Bush Administration is associated. Obama, like President Bush, still prioritizes military solutions in Iraq and puts more emphasis on hunting al-Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan by redeploying troops there, but he pays less attention to the sociological conditions of the region where the al-Qaeda generation predominantly mushrooms out. Obama, much as his predecessor, ignores the conditions of desperation of much of the Muslim world, as well as the Muslim cultural sensitivity to direct and indirect occupations. According to Francois Burgat, this desperation is the product of three ill-managed domains of politics: the global domain (occupied by the United States), Arab-Israeli domain, in which the US as the superpower is reluctant or refuses to regulate, and national Arab domains where totalitarianism gives no chance to emerging democratic representations (See Burgat, 2009).

However, Obama still possesses the post-Bush momentum which may give birth to essential policy changes and create new nets of opportunities. This policy change may not occur overnight, but at least the will and decisiveness for change must be shown to the people of the region in a concrete way. In this sense, Obamas first visit to the Muslim countries, Turkey and Egypt, are crucial and admirable steps to bridge the gap between the non-violent Muslim majority population and the US.

Suggestively, both Europe and the US must abandon the politics of constant denial of "other" dissident political voices, including Hamas of Palestine and Hezbollah of Lebanon. These organizations possess tremendous social power over the public beyond their military capabilities in their country. Hezbollah of Lebanon, for instance, acts not only the protector of Lebanese territory during foreign invasion, but also contributes to rebuilding and growth of their country during the peace times. More often, they accomplish better job than Beirut Administration with providing economic and social sustainability to the country. Thus, peace in the Middle East cannot be achieved without recognizing and denying the existence of these dissident Muslim currents in the region. Once again, Europe and the US have showed how weak they were when it comes to putting pressure on Israels illegal raid to the Gaza Flotilla in 2010 (See Milliyet, 2010) and blockade of Gaza ports. It is crucial for Europe and the US to pursue respectful political relations, not only with proponent parties but also with "other" opposite Islamic currents. In addition to that, particularly the US must implement inclusive policies that respect both Palestine and Israel, and do away with the doctrine of unconditional Israeli exceptionalism in the Middle East, so that the region under US leadership resumes a path toward long-term sustainable peace. To do this, the current administration should immediately desert Bushs aggressive democratization and revisit and adjust military action as it concerns the Middle East question.

Conclusion

For more than fifty years, US relations with the Middle East mainly dwelled around two major issues: security of Israel and Arab oil fields. However, over time, these two fundamental objectives of the US Middle East agenda produced many other complexities and dilemmas. Thus, US objectives would include democratization of the region, indirect control of Arab states, modernizing local cultures and people, and engaging in proxy wars to contain Communism and, later, radical Islam from spreading to other regions. But, none of USs Middle East policies and objectives seriously addressed the Israeli-Palestinian territorial conflicts, and none of the US goals for the region showed significant evidences to avoid indiscriminate ostracism of all oppositional political voices in the Muslim world. The US stayed ignorant of the sociological dynamics of Islamic cultural currents and became the victim of Israeli exceptionalism in the region.

Europe, on the other hand, struggles to maintain its politics of "no trouble" in Middle Eastern approaches to regional issues. Europe acknowledges the regional issues, such as the illegality of Israeli settlements and Gaza blockades, but it does little to change the course of illegality and Israeli oppression on the ground. This double standard of Europe toward Israeli-Palestinian issues weakens Europe, and prevents it from taking strong actions against Arab totalitarianism, human rights violations, and anti-democratic developments in the Middle East. Europes moral and political responsibilities in the Middle East diminish by Europes inactive stands against Israel. When increasing Islamophobia in Europe is added to the whole picture, Muslim peoples trust and belief in Europes conciliatory position shrinks fast and, ultimately, it jeopardizes non-violent alternatives to Arab-Israeli conflicts. According to Amr Hamzawy "[T]he US and the EU must initiate relations with moderate Islamists, which is not so prickly as it might seem, because these Islamists have taken on board democratic rules and shown themselves to be a very support for the Rule of Law" (See Burgat, 2009, p. 633). Thus, a possible solution in the Middle East lies in an honest acknowledgement of local dissident political voices and paying credible attention to the sociology of regional conditions (See Harvey, 2009; Hamzawy, 2005 and Burgat, 2009, p. 633).

To come to this point, the US and Europe will probably risk serious disagreements with Israel and will have to push for tougher sanctions against Israels illegal military campaigns against Palestinian people. In this context, the US and Europe still give the impression to be the only political actors in the world to accomplish long-term sustainable peace in the Middle East. Failure to do this will result in regional insecurity and will continue to jeopardize long-term peace endowments, not only in the Middle East but also in the hearts of Europe and the Atlantic world, as seen in the New York and Madrid terrorist attacks of 2001 and 2005, respectfully. For this reason, the post-9/11 moment should be reread carefully by Western actors, and they should pay serious attention to the sociology of Islamic dynamics and collective resistance in the Middle East. This task is not impossible, but it is certainly challenging.

Notes

* This research is part of the project "Middle Eastern Politics in the 21st Century" developed at the University of Oklahoma, EEUU.

[1] Edward Said, for instance, asks this question: How we have come to think of the Middle East in a certain way? To answer to his question, he investigates popularly consumed cultural productions of Hollywood film industry and explains that the way in which Hollywood represents Middle East and Islam is not accidental, innocent or totally detached from real geopolitics. He finds that Hollywood film industry constantly and consciously portrays Middle Eastern people as villain, barbaric, and blood thirsty. For him, Hollywood films repeatedly frame the geography of Arabic culture inhabitable, undeveloped, and unmanageable. To read more about this subject, see Saids book Covering Islam: How the Media and Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World.

[2] In this article, the Bush Administration refers to the Presidency of George W. Bush unless specified.

[3] Though the US sought a United Nation (UN) resolution before waging war on Taliban regime in Afghanistan, I would contend that free nations of the world did not have enough freedom to question USs military action over Afghanistan. The fear was to be accused of supporting the uncooperative government of Taliban. The post-9/11 moment, to me at least, left no room for the world governments to oppose USs war on Afghanistan.

[4] I do not believe that the difference in timeline between the Afghan and the Iraq War leads to a possible conspiracy of neo-conservative plans at the outset, although toppling Saddams regime was not a new phenomenon for the state secretaries of the Bush Administration even before 9/11.

References

1. Anceschi, Luca, Joseph Camilleri , & Fabio Petito. (2009). Europe, the United [ 193 ] States and the Islamic World: Conceptualising a triangular relationship. International Politics, 46(5), 505-516. [ Links ]

2. Burgat, François. (2009). Europe and the Arab World: The Dilemma of Recognising Counterparts. International Politics, 46(5), 616-635. [ Links ]

3. Calleo, David. (2004). The Broken West. Survival , 46 (3), 29-38. [ Links ]

4. Crosston, Matthew. (2009). Neoconservative Democratization in Theory and Practice: Developing Democrats or Raising Radical Islamists? International Politics, 46 (2/3), 298-326. [ Links ]

5. Daily News. (June 24, 2010). Obama at War: President must make Afghan strategy work without McChrystal [on line]. Daily News. Available in: http://articles.nydailynews.com/2010-06-24/news/29437750_1_mcchrystal-vice-president-bidenpresident-obama/2 [Retrieved June 24, 2010]. [ Links ]

6. Dalby, Simon. (2009). Geopolitics, the Revolution in Military Affairs and the Bush Doctrine. International Politics, 46(2/3), 234-252. [ Links ]

7. Diez, Thomas. (2004). Europes Others and the Return of Geopolitics. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 17 (2), 319-335. [ Links ]

8. Dittmer, Jason. (2010). Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [ Links ]

9. Fukuyama, Francis. (2004). State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century. NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

10. Halabi, Yakub. (2009). US foreign Policy in the Middle East: From Crises to Change. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company. [ Links ]

11. Hamzawy, Amr. (2005, August). The Key to Arab Reform: Moderate Islamist [on line]. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 40. Available in: http://www.carnegieendowment.org/publications/index.cfm?fa=view&id=17258&prog=zgp&proj =zdrl. [Retrieved May 10, 2006]. [ Links ]

12. Harvey, David. (2009). Cosmopolitanism and the Geographies of Freedom. New York: Colombia University Press. [ Links ]

13. Jones, Alun, & Jullian Clark. (2008). Europeanisation and Discourse Building: The European Commission, European Narratives and European Neighbourhood Policy. Geopoltics, 13 (3), 545-571. [ Links ]

14. Lewis, Jeffery. (2009). EU policy on Iraq: The Collapse and Reconstruction of Concensus-based Foreign Policy. International Politics, 46 (4), 432-450. [ Links ]

15. Kurth, James. (2006). Europes Identity Problem and the New Islamist War. Foreign Policy Research Institute. Summer, 541-557. [ Links ]

16. Matthes, C. Felix (2004). European Union Energy Policy. In: Encyclopedia of Energy (Vol. 2, pp. 557-567). Berlin, Germany: Elsevier Inc. [ Links ]

17. Milliyet (July 13, 2010). Mavi Marmarada Hatalarimiz Oldu [on line]. Milliyet. Available in:http://www.milliyet.com.tr/mavi-marmara-da-hatalarimiz-oldu/dunya/ haberdetay/13.07.2010/1262801/default.htm [Retrieved May 10, 2010]. [ Links ]

18. Ozkan, Mehmet. (2007). Turkey in the Islamic World: An Institutional Perspective. Turkish Review of Middle East Studies, 18, 159-193. [ Links ]

19. Parmar, Inderjeet. (2009). Foreign Policy Fusion: Liberal Interventionists, Conservative Nationalists and Neoconservatives the New Alliance Dominating the US Foreign Policy Establisment. International Politics , 46 (2/3), 177-209. [ Links ]

20. Said, W. Edward. (1997). Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

21. Sandole, J.D. Dennis. (2009). Turkeys Unique Role in Nipping in the Bud the "Clash of Civilizations". International Politics, 46 (5), 636-655. [ Links ]

22. Smith, Michael. (2009). Between "Soft Power" and a Hard Place: European Union Foreign and Security Policy between the Islamic World and the United States. International Politics, 46 (5), 596-615. [ Links ]

23. US Energy Information Administration. (2010). EIAs Latest Weekly Petroleum Analysis [on line]. Available in: http://www.eia.gov/petroleum/ [Retrieved Februray 10, 2010]. [ Links ]

24. Watkins, Eric. (1997). The Unfolding US Policy in the Middle East. International Affairs, 73 (1), 1-14. [ Links ]

25. Zunes, Stephen. (2009). Peace or Pax Americana? US Middle East Policy and the Threat to Global Security. International Politics, 46 (5), 573-595. [ Links ]

Fecha de recepción: febrero de 2011

Fecha de aprobación: abril de 2011

How to quote this article

Anaz, Necati. (2011, enero-junio). Understanding the contemporary United States and European Union foreign policy in the Middle East. Estudios Políticos, 38, Instituto de Estudios Políticos, Universidad de Antioquia, (pp. 175-194).