Gabapentin Relevance and General Description

The potential of anticonvulsants for treating addiction problems has been pointed out in the literature (Zullino, Khazaal, Hattenschwiler, Borgeat & Besson, 2004). Among the advantages offered by anticonvulsants are: (a) they facilitate an easy and safe detoxification process, (b) their relative lack of addiction potential, (c) they protect from potential seizures elicited during withdrawal process, and (d) their usefulness for treating comorbid psychiatric disorders found in addict subjects (Zullino et al., 2004). Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant, has reported potential for treating cocaine dependence, and for facilitating alcohol and benzodiazepine detoxifications (Zullino et al., 2004). Also, Gabapentin is considered to be relatively safe compared to other pharmaceutical drugs for alleviating substance-related problems (Howland, 2014).

Gabapentin is a pharmaceutical drug with a physical appearance of a white crystalline solid. Gabapentin's molecular formula is C9 H17 NO2 and its molecular weight is 171.23678 g/mol. This drug has different brand names like Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant, and Fanatrex (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2018). In the drugstore market, Gabapentin can be sold in the form of tablets or capsules of different doses (tablets: 300, 600 and 800 mg, and capsules: 100, 300 and 400 mg; Drug Information Portal, 2018).

Gabapentin has diverse pharmacodynamical and pharmacokinetic properties (Bockbrader et al., 2010). It is absorbed slowly after oral administration (compared to Pregabalin), and it has maximum plasma concentrations within 3 to 4 h; moreover, oral administration of Gabapentin has a saturable absorption (a nonlinear process, zero-order; Bockbrader et al., 2010). On the other hand, Gabapentin's plasma concentration does not increase proportionally if its doses are augmented, and it does not bind to plasma proteins (Bockbrader et al., 2010). Finally, Gabapentin is neither inhibited nor metabolized by hepatic enzymes; moreover, Gabapentin can be excreted by the renal route, and its elimination half life is approximately 6 h (Bockbrader et al., 2010).

Gabapentin Mechanisms of Action

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant drug that decreases neuronal transmission by inhibiting presynaptic voltage-gated calcium and sodium channels (Dickenson & Ghandehari, 2007; Landmark, 2007; Rogawski & Loscher, 2004), thus inhibiting exocytosis and the release ofneurotransmitters from presynapses (Coderre, Kumar, Lefebvre, & Yu, 2007; Cunningham, Woodhall, Thompson, Dooley, & Jones, 2004). Moreover, Gabapentin inhibits synaptogenesis by binding to (X2S1 subunit of calcium channels (Bauer, Tran-Van-Minh, Kadurin, & Dolphin, 2010; Eroglu et al., 2009); specifically, Gabapentin antagonizes the interaction between (X2S1 subunit and glial released thrombospondins, hence inhibiting the promotion of excitatory synapses. One of the advantages of Gabapentin is its low side effects and toxicity. However, some recent clinical reports from Europe questioned this and have warned about possible side effects (No author listed, 2012) of Gabapentin like addiction and withdrawal symptoms, even in patients without previous history of substance abuse.

Gabapentin Use in Research

Gabapentin is a drug that has been the subject of research in human and other vertebrates for a few decades (Hengy & Kolle, 1985; Reimann, 1983; Schlicker, Reimann, & Gothert, 1985; Vollmer, von Hodenberg, & Kolle, 1986). The initial focus of research on Gabapentin was the alleviation of epilepsy (Bartoszyk & Hamer, 1987; Crawford, Ghadiali, Lane, Blumhardt, & Chadwick, 1987). Later, Gabapentin was explored for treating other conditions like behavioral decontrol and psychiatric diseases (Ryback & Ryback, 1995; Walden & Hesslinger, 1995), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Welty, Schielke, & Rothstein, 1995), reducing nociception (Rosner, Rubin, & Kestenbaum, 1996; Shimoyama, Shimoyama, Inturrisi, & Elliott, 1997), anxiety (Singh et al., 1996), neuralgia (Segal & Rordorf, 1996), restless legs syndrome (Adler, 1997; Mellick & Mellick, 1996), bipolar disorder (Ryback, Brodsky, & Munasifi, 1997) and others (No author listed, 2012).

The main purpose of this study is to provide an updated review of the use of Gabapentin in treating opioid, cannabis, and methamphetamine use disorders. Different reviews (non-specialized in Gabapentin) have described the use of Gabapentin for treating these substances; specifically, reviews dealing with opioid consumption problems (Berlin, Butler, & Perloff, 2015; Olive, Cleva, Kalivas, & Malcolm, 2012; Rodriguez-Arias, Aguilar, & Minarro, 2015; Soyka & Mutschler, 2016), cannabis consumption problems (Balter, Cooper, & Haney, 2014; Gorelick, 2016; Howland, 2013; Marshall, Gowing, Ali, & Le Foll, 2014; Sabioni & Le Foll, 2018), and methamphetamine consumption problems (Brackins, Brahm, & Kissack, 2011; Howland, 2013; Karila et al., 2010).

As a reference, Gabapentin has been used for treating other substance-related problems, for instance, alcohol-related problems (Ahmed et al., 2019; Berlin et al., 2015; Howland, 2013; Howland, 2014; Soyka & Mutschler, 2016). At least some benefit has been reported for treating cravings (Ahmed et al., 2019; Berlin et al., 2015), withdrawal symptoms (Ahmed et al., 2019; Berlin et al., 2015; Howland, 2013), and alcohol dependence (Howland, 2013; Howland, 2014; Soyka & Mutschler, 2016). However, Gabapentin has not shown benefit for treating cocaine dependence (Ahmed et al, 2019; Howland, 2013; Minozzi et al., 2015) or tobacco dependence (Sood et al., 2010).

As a reference, other substances that have been use for treating opioid consumption problems are: new dosage forms of Buprenorphine, new extended-release forms of Naltrexone (Rodriguez-Arias et al., 2015), opioid agonist therapy with Methadone or Buprenorphine (opioid dependence), oral or Depot Naltrexone, Morphine Sulfate, depot or implant formulations, and heroin (Diacetylmorphine) in treatment-refractory patients (Soyka & Mutschler, 2016). Others substances for treating methamphetamine use problems are: Modafinil, Bupropion, Naltrexone (reducing amphetamine or methamphetamine use), d-amphetamine and methylphenidate (agonists replacement medication) based on Karila et al. (2010). Finally, other pharmaceutical drugs explored for alleviating cannabis consumption problems and showing some promise are: Propranolol (some intoxication symptoms), antipsychotics (cannabis-induced psychosis), Dronabinol (cannabis withdrawal), and N-acetylcysteine (cannabis used disorder in adolescents) based on Gorelick (2016).

It is important to mention, that some works have proposed the presurgical use of Gabapentin to reduce postsurgical use of opioids. For instance, a recent meta-analysis, and two recent experimental works on patients undergoing different types of surgeries support this (Arumugam, Lau, & Chamberlain, 2016; Hah et al., 2018; Mardani-Kivi et al., 2016). Specifically, this meta-analysis (Arumugam et al., 2016) based on 17 randomized control trials (n=1,793 patients) concluded that presurgical Gabapentin reduced postoperative opioid consumption (morphine, Fentanyl, and Tramadol) during the initial 24 h after surgery; also, there were no changes in nausea and vomiting incidences. However, Gabapentin significantly increases postoperative somnolence.

On the other hand, the clinical research work of Mardani-Kivi et al. (2016) evaluated the effect of preemptive Gabapentin (single dose) on opioid consumption and pain management in a group of patients (n=76) undergoing surgery (Arthroscopic Bankart). This work concluded that Gabapentin reduced opioid consumption (at 6 and 24 h), and nausea and vomiting (6 h) after surgery; moreover, Gabapentin did not induce differences in pain intensity, dizziness, or sedation. The other experimental work (Hah et al., 2018) studied the effect of perioperative Gabapentin on remote postoperative time to pain resolution and opioid cessation, in a cluster of patients (n=410) undergoing a diverse range of surgeries (thoracotomy, total knee replacement, total hip replacement, mastectomy, lumpectomy, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, hand surgery, carpal tunnel surgery, knee arthroscopy, shoulder arthroplasty, and shoulder arthroscopy).

Finally, there are different points of views regarding Gabapentin safety and potential of abuse (Howland, 2014; Quintero, 2017). According to Howland (2014) Gabapentin is not particularly dangerous; it has potential of misuse, but it can be regarded as safe and adequate for treating substance use disorders. On the other hand, another revision by Quintero (2017) warned that Gabapentin has the risk of being misused, like other substances, and it has potential interactions with other substances (morphine, caffeine, Losartan, ethacrynic acid, phenytoin, mefloquine and magnesium oxide). Moreover, Gabapentin can be contraindicated in conditions like myasthenia gravis and myoclonus (Quintero, 2017). Taking these together, Gabapentin could be considered as a drug with no major risks compared to the average substance, but precaution should be taken regarding potential interactions and contraindications.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The research studies were chosen according to the following inclusion criteria: (a) human or non-human studies, (b) experimental or quasi-experimental design, (c) research that includes description about the effect of Gabapentin for treating opioids, cannabis, or methamphetamine use disorders or related disorders (addiction or consumption), (d) the studies should be mainly experimental, quantitative, or clinical , (e) research that described the number of participants, (f) the studies could use Gabapentin alone or combined with other drug(s), (g) written in English (at least title and abstract), (h) a temporal range limit in the database used: January-1983 to May-2018.

January of1983 was selected because it was the year of the first Gabapentin publication in PubMed. Revisions were also included, but mainly for the introduction section.

Regarding the exclusion criteria, these included: (a) noncompliance with the inclusion criteria, and (b) they should not be abstracts, publications of scientific meetings, or research included in nonscientific literature.

Inquiry Strategy

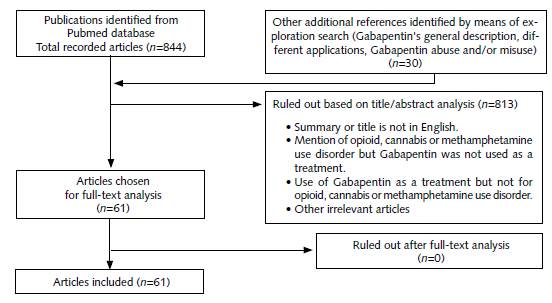

The search was performed between Janu-ary-l983 and May-20l8, using the following database: PubMed. The key words used were: Gabapentin, opioids, cannabis and methamphet-amine. The search terms used were combined as follows: "Gabapentin and opioids", "Gabapentin and cannabis", and "Gabapentin and methamphet-amine". Initially, 844 references were obtained in the output of the PubMed database; additionally, another 30 references were identified through reference exploration or web search. These 30 complementary references were related mainly to Gabapentin's general description and its misuse. After analysis of the title and abstract, 8l3 references were ruled out, resulting in 61 references for further analysis. The references were ruled out due to different factors like: (a) literature review or meta-analysis type, (b) non-English language, (c) Gabapentin was used for treating problems with susbstances other than opioids, methamphetamine, or cannabis, (d) there was mention of opioids, methamphetamine, or cannabis substance-abuse problems, but Gabapentin was not described as treatment, (e) Gabapentin was used as treatment, but for other health problems not related to addiction (for instance, pain), (f) duplicates and (g) other irrelevant articles. The complete versions of the 6l references were downloaded or requested from the authors and were analyzed for preparation of the review. After analysis of the full version of the articles, a total of 61 references were selected for the review; more details are described in Figure 1.

The Method for Estimating Gabapentin Success in Treating Substance Use Problems

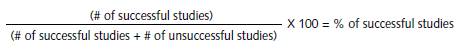

The estimation of success was expressed in percentages. The percentages were calculated by means of the formula described in Figure 2.

A study was considered successful if it fulfilled any of the following conditions:

If Gabapentin alone (uncombined with other drug or treatment) was compared to a control group (generally placebo) only, and it surpassed the control condition.

If Gabapentin combined with other drug or treatment was compared to a control group only, and the combination surpassed the control condition.

If Gabapentin alone was compared to other drugs and to a control group, and Gabapentin surpassed the other conditions.

If Gabapentin combined with other drug or treatment were compared to other drugs and to a control group, and the Gabapentin combination surpassed the other conditions.

If Gabapentin alone or combined with other drug or treatment demonstrated effectiveness for treating a condition, but no control group was included; for instance, as in clinical studies with low sample.

To estimate the percentage of successful studies, a formula was used, which consists in dividing the number of successful studies among the total number of studies carried out (successful and unsuccessful). Later the result of this division was multiplied by 100.

Results and Discussion

Gabapentin Use in Treating Opioid-Related Problems

Research on the use of Gabapentin in treating opioid-related problems have included aspects like withdrawal symptoms (Kheirabadi, Ranjkesh, Maracy, & Salehi, 2008; Martinez-Raga, Sabater, Perez-Galvez, Castellano, & Cervera, 2004; Moghadam & Alavinia, 2013; Rudolf et al., 2018; Salehi, Kheirabadi, Maracy, & Ranjkesh, 2011; Ziaaddini, Ziaaddini, Asghari, Nakhaee, & Eslami, 2015), and the reduction of opioid consumtion during detoxification (Sanders et al., 2013).

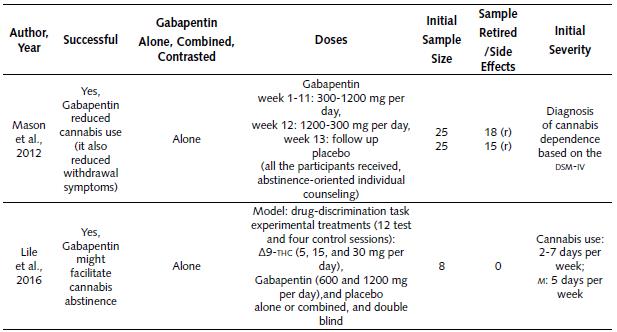

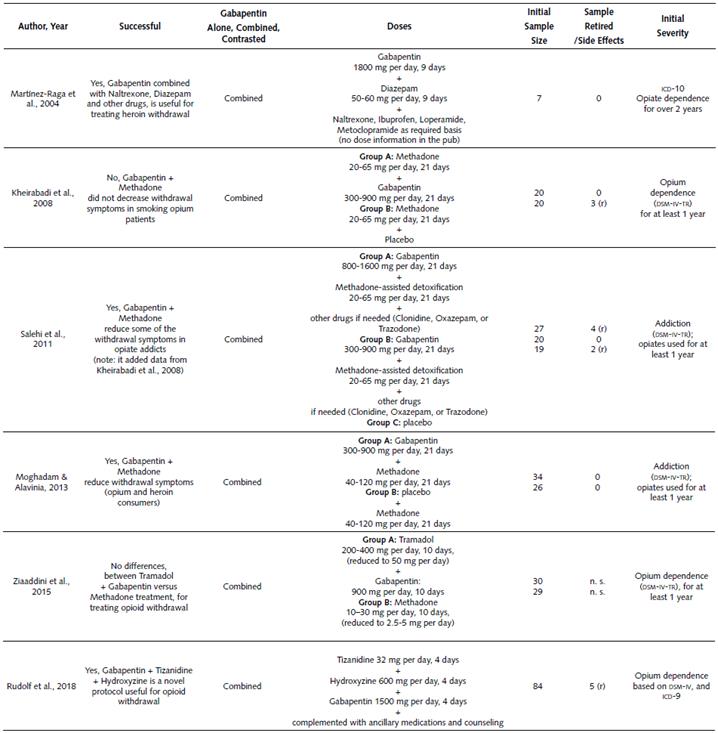

Clinical Studies on the Use of Gabapentin in Treating Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms. Table 1 describes diverse clinical studies about the use of Gabapentin for treating opioid withdrawal symptoms. Based on the information in Table 1, it is possible to state the following:

Gabapentin was employed in a total of six studies between the years 2004 and 2018. All these studies combined Gabapentin with another drug for exploring reduction of opioid withdrawal symptoms.

In general, successful results were published in four out of six studies (66.7%) (Kheirabadi et al., 2008; Martinez-Raga et al., 2004; Moghadam & Alavinia, 2013; Salehi et al., 2011).

The first successful study combined Gabapentin with Diazepam, Naltrexone and other drugs (Martinez-Raga et al., 2004). The dose of Gabapentin used was 1800 mg per day for a total of 9 days of treatment. The dose of Diazepam employed was 50-60 mg per day for a total of 9 days of treatment. The doses of the other drugs were not specified in the publication (Naltrexone, Ibuprofen, Loperamide, and Metoclopramide). Finally, the overall initial sample of this work was a total of seven subjects.

The second successful study combined Gabapentin and Methadone during a Methadone assisted detoxification (Salehi et al., 2011). The Gabapentin dose used was 800-1600 mg per day during 3 weeks; moreover, the methadone dose was 20-65 mg per day during 3 weeks. The 1600 mg dose (Gabapentin) reduced some of the withdrawal symptoms (coldness, diarrhea, dysphoria, yawing, and muscle tension). As a reference, this study was a continuation of a first phase study that employed a Gabapentin dose of 300-900 mg per day during 3 weeks. The initial sample of the study was 27 subjects.

The third successful study combined Gabapentin and Methadone (Moghadam & Alavinia, 2013), and it was useful for reducing withdrawal symptoms (opium and heroin consumers). This study contrasted two clusters. The doses of the first cluster combined Gabapentin (300-900 mg per day) and Methadone (40-120 mg per day); these treatments lasted for 21 days. The second group doses consisted of placebo and Methadone (40-120 mg per day) and lasted for 21 days. The sample for each cluster was 34 and 26 subjects respectively.

The fourth successful study combined Gabapentin (1500 mg per day), Hydroxyzine (600 mg per day) and Tizanidine (32 mg per day) during 4 days of treatment (Rudolf et al., 2018). The participants also received auxiliary medications based on necessity and standard treatment. As a reference, this investigation used a novel protocol that does not rely on opioid agonists or other controlled substances; it reported effectiveness for alleviating opioid withdrawal symptoms. The overall initial sample of this work was 84 subjects.

Another study did not find differences between treatment groups. Specifically, this study combined Gabapentin and Tramadol (Ziaaddini et al., 2015), and it demonstrated that the combination alleviates opioid withdrawal in a similar way to the other condition. The two experimental clusters were: first one, consisting in a combination of Gabapentin (900 mg per day) and Tramadol (200-400 mg per day, reduced to 50 mg per day), for 10 days. The second cluster included 10-30 mg per day of Methadone, and it lasted 10 days (reduced 2.5-5 mg per day). The sample for each group was 30 and 29 subjects respectively.

The only study that failed to reduce withdrawal symptoms combined Gabapentin and Methadone (Kheirabadi et al., 2008). As a reference, the participants in this study were opium smokers, and maybe the route of drug administration could influence the effectiveness of Gabapentin. This study compared two groups. The first group was treated with a combination of Gabapentin (300-900 mg per day) and Methadone (20-65 mg per day) for 21 days. The second group was treated with 20-65 mg per day of Methadone for 21 days. The initial sample was 20 participants per cluster, but three subjects withdrew from the second cluster.

Table 1 Summary of the Clinical Investigations on the Use of Gabapentin for Treating Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms

Note:

DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-fourth edition- text revision

ICD-9: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems- ninth revision

ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-tenth revision

mg: milligram

n.s.: non specified

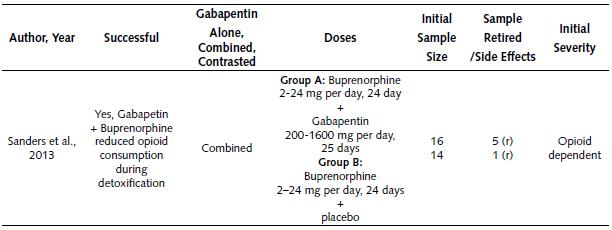

r: retired

Clinical Studies on the Use of Gabapentin for Reducing Opioid Consumption during Detoxification. Table 2 describes the only clinical study about the use of Gabapentin for reducing opioid consumption during detoxification. Based on the information in Table 2, it is possible to state:

The only study was performed in the year 2013, and it reported a successful result (Sanders et al., 2013).

Gabapentin was combined with another drug (Buprenorphine), and this combination successfully reduced the intake of opioids.

This study compared two groups. The treatment for the first group consisted of a combination of Gabapentin (200-1600 mg per day) and Buprenorphine (2-24 mg per day). The second group medication combined placebo and Buprenorphine (2-24 mg per day). Treatments lasted 24 to 25 days. The initial sample per group was 16 and 14 subjects respectively (five and one subject withdrew respectively).

Table 2 Summary of Clinical Study on the Use of Gabapentin for Reducing Opioid Consume During Detoxification

Note: mg: milligram; r: retired

Gabapentin Use in Treating Methamphetamine-Related Problems

The majority of studies about the feasibility of using Gabapentin to treat methamphetamine consumption problems have been restricted to its dependence (Heinzerling et al., 2006; Ling et al., 2012; Urschel, Hanselka, & Baron, 20ll; Urschel, Hanselka, Gromov, White, & Baron, 2007). On the other hand, one basic rodent research has investigated the effects of Gabapentin on methamphetamine place preference (Kurokawa, Shibasaki, Mizuno, & Ohkuma, 2011).

Clinical Studies about the Use of Gabapen-tin for Reducing Methamphetamine Dependence.

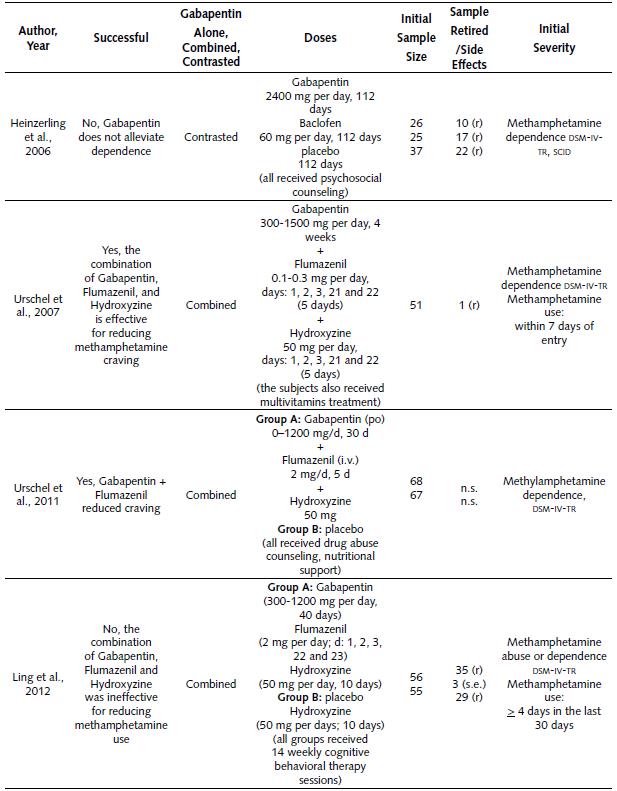

Table 3 explains the different clinical studies about the use of Gabapentin for reducing methamphetamine dependence. According to the information in the table, we can make the following statements:

Gabapentin was employed in a total of four studies between the years 2006 and 2012. Successful results were reported in two out of four studies (50%).

One study compared Gabapentin alone against other drugs, for reducing methamphetamine dependence (Heinzerling et al., 2006). Moreover, three different studies evaluated the effectiveness of Gabapentin combined with another drug for reducing methamphetamine dependence.

The only two successful studies combined Gabapentin, Flumazenil and Hydroxyzine (Urschel et al., 2007;.Urschel et al., 2011). Both studies reported that the combination was able to reduce methamphetamine craving.

The first study that combined Gabapentin with another drug used a single experimental group. This study contrasted methamphetamine consumption before and after treatment (Urschel et al., 2007). This study combined Gabapentin (300-l500 mg per day) during 4 weeks, Flumazenil (0.1-0.3 mg per day) during 5 days, and Hydroxyzine (50 mg per day) during 5 days. Furthermore, all the subjects received multivitamin treatment. The study was an open label, and it lacked a placebo group. The initial sample was 51 subjects (one subject withdrew from the study).

The second study (Urschel et al., 2011) that combined Gabapentin with other drugs had two experimental groups. The treatment of the first group was Gabapentin (0-1,200 mg per day) during 30 days, Flumazenil (2 mg per day) during 5 days, and Hydroxyzine (50 mg, no days specified). The other group was the placebo. As a reference, both groups also received drug abuse counseling and nutritional support. The sample per group was 68 and 67 subjects respectively.

On the other hand, two other studies failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of Gabapentin for reducing methamphetamine dependence: the first one contrasted Gabapentin against Baclofen (Heinzerling et al., 2006), and the second one explored the combination of Gabapentin, Flumazenil and Hydroxyzine (Ling et al., 2012).

The first failed study contrasted Gabapentin against Baclofen (Heinzerling et al., 2006) and the doses employed were the following: 2400 mg per day of Gabapentin (112 days), 60 mg per day of Baclofen (5 days), and placebo (112 days). Besides this, all the subjects received psychosocial counseling. The initial sample of each group was: 26 (Gabapentin), 25 (Baclofen) and 37 (placebo); however, 10, 17 and 22 subjects retired from each cluster respectively.

The second failed study combined Gabapentin, Flumazenil and Hydroxyzine (Ling et al., 2012), and utilized two experimental groups. For the first group, the treatment executed was: 300-1200 mg per day of Gabapentin (40 days), 2 mg per day of Flumazenil (5 days), and 50 mg per day of Hydroxyzine (10 days). The second group (placebo) treatment was: 50 mg of Hydroxyzine per day (10 days) and medical placebos of Gabapentin and Hydroxyzine. Moreover, all the participants in the study received 14 weekly cognitive behavioral therapy sessions. The initial sample was 56 and 55 participants respectively for each group. A total of 38 and 29 subjects withdrew from the study respectively.

Table 3 Summary of Clinical Studies About the Use of Gabapentin for Reducing Methamphetamine Dependence

Note:

DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-fourth edition-text revision

iv: intravenous

mg: milligram

ns: non specified

po: per os

r: retired

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

s.e.: side effects

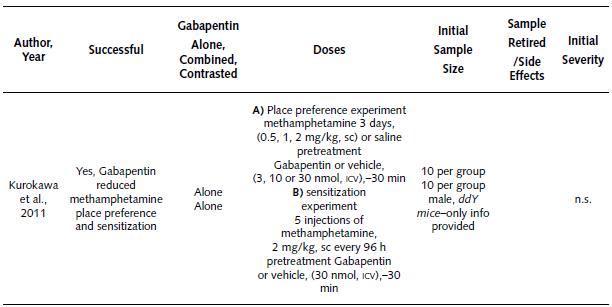

Basic Study about the Effect of Gabapentin on Methamphetamine Place Preference and Sensitization. Table 4 summarizes the only animal study about the effects of Gabapentin on methamphetamine place preference and sensitization. Based on the information in this table, it is possible to state:

The single study was performed in 2011 (Kurokawa et al., 2011), and it reported a successful result in the reduction of methamphetamine place preference and sensitization.

This study was performed in male DDY mice.

This tested by means of two different experiments. In the first one (place preference), the treatment (Gabapentin or vehicle) was applied 30 min before the challenge (methamphetamine or saline). Gabapentin (dose of 3, 10 or 30 nmol) and the vehicle were injected into the brain via intracerebroventricular (ICV) route. For the challenges (methamphetamine or saline) the doses used were 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/kg subcutaneous (SC) route, and during 3 days. The first experiment employed an initial sample of eight mice per group.

On the other hand, the second experiment (sensitization) employed a Gabapentin or vehicle treatment 30 min before the challenge (methamphetamine or saline). The Gabapentin (dose of 30 nmol) or vehicle was injected into the brain (ICV route). The methamphetamine challenge consisted of five injections (2 mg/ kg, SC route), every 96 hours. The sample was 10 mice per group.

Gabapentin Use in Treating Cannabis Related Problems

A couple of rseearch projects have explored Gabapentin for alleviating cannabis consumption problems, and they were about cannabis dependence and withdrawal symptoms (Mason et al., 2012).

Clinical Studies on the Use of Gabapentin for Reducing Cannabis Dependence. Table 5 summarizes the two clinical studies about the use of Gabapentin for reducing cannabis dependence symptoms (Lile, Wesley, Kelly, & Hays, 2016; Mason et al., 2012). The following assertions can be made:

Both studies (2012 and 2016) reported successful results (100% success).

Gabapentin was used uncombined (not combined with another drug) in both studies.

The studies followed a different approach: the study by Mason et al.(2012) tested Gabapentin doses in the range of 300-1200 mg per day, during 12 weeks, and the 13th week was for follow- up; a placebo group was included. In addition, all the participants of this study received abstinence-oriented individual counseling. More details are described in Table 5.

On the other hand, the study by Lile et al. (2016) used a drug-discrimination task paradigm. It consisted of 12 test sessions and four control sessions. The experimental conditions were ∆9-THC (delta-9-tetrahidrocannabinol: 5, 15 and 30 mg per day), Gabapentin (600 and 1200 mg per day), and placebo. More details are explained in Table 5.

As a reference, the Mason et al. (2012) study also reported that Gabapentin alleviated cannabis withdrawal symptoms.

Table 4 Summary of Basic Study About the Effects of Gabapentin on Methamphetamine Place Preference and Sensitization

Note: ICV: intracerebroventricular; h: hours; mg/kg: milligram per kilogram; min: minutes; nmol: nanomole; n.s.: non specified; SC: subcutaneous

General Conclusions for Each Section

Conclusions about the Use of Gabapentin for Treating Opioid-Related Problems

For treating problems of opioid withdrawal symptoms, Gabapentin has been effective in 66.7% (4/6) of the studies reported between 2004 and 20l8. Each of these successful studies included the following drug combinations: (a) Gabapentin + Diazepam + Naltrexone + other drugs (one study), (b) Gabapentin + Methadone (two studies), or (c) Gabapentin + Hydroxyzine + Tizanidine (one study). However, another study reported a negative result applying the combination of Gabapentin and Methadone. It is evident that the Gabapentin and Methadone combination has produced inconsistent results for treating opioid withdrawal symptoms; more research is necessary to define its suitability. A possible explanation for this inconsistency is the route of administration of the opioid; Gabapentin failed in treating opium smokers (inhalation route). Maybe, the route of opioid administration (inhalation) could influence Gabapentin effectiveness.

Moreover, it is advisable to perform more studies for the following drug combinations: (a) Gabapentin + Diazepam + Naltrexone, and (b) Gabapentin + Hydroxyzine + Tizanidine; because only one study reported positive results for each of these combinations.

For treating opioid withdrawal symptoms Ga-bapentin has shown some effectiveness as adjuvant (combined) with other drugs, and not as single treatment. The effective results can be grouped in those consisting of Methadone assisted, and non-Methadone assisted (used different drugs). For those related to Methadone-assisted strategies (relying on agonists), the treatment of Gabapentin was 1600 mg per day, and Methadone 20-65 mg per day during 3 weeks; also, 300-900 mg per day of Gabapentin, and 40-120 mg per day of Methadone during 3 weeks. Regarding non-Methadone-assisted strategies, the treatment of Gabapentin was 1500 mg per day, and 600 mg per day of Hydroxyzine, and 32 mg per day of Tizanidine, for 4 days; also, 1800 mg per day of Gabapentin, and 50-60 mg per day of Diazepam, during 9 days.

Another line of research explored the use of Gabapentin for reducing opioid consumption during a detoxification process; there was only one successful study performed in 20l3. Specifically, in this study Gabapentin was combined with Buprenorphine, and this combination surpassed the single effect of Buprenorphine. As a reference, the doses for Buprenorphine were 12 mg per day (first 14 days) followed by tapering up to 2 mg per day (next lo days); regarding Gabapentin dosage, the treatment began l week later and consisted of l6oo mg per day (21 days) followed by tapering up to 200 mg per day (next 3 days). Due to scarcity of research, more studies are recommendable to confirm Gabapentin's suitability as a treatment for opioid detoxification.

Conclusions about the Use of Gabapentin for Alleviating Methamphetamine-Related Problems

Gabapentin was explored for alleviating methamphetamine dependence problems in four studies performed between 2006 and 2012; 50% (2/4) of the studies showed successful results. Both studies with favorable results combined Gabapentin, Flumazenil and Hydroxyzine. Also, this combination helps to decrease methamphet-amine craving. However, another study reported a failure using the same combination (Gabapentin, Flumazenil, and Hydroxyzine). Based on this inconsistency, it seems advisable to perform further studies to define the suitability of this combination as a treatment for methamphetamine dependence.

Successful studies applied Gabapentin as adjuvant (combined) with the use of other pharmaceutical drugs. The two successful studies used the following range of doses: the first study used 300-1500 mg per day of Gabapentin (4 weeks), 0.1-0.3 mg per day of Flumazenil (5 days), and 50 mg per day of Hydroxyzine (5 days). The other successful study started with very low doses (o mg) up to l500 mg per day of Gabapentin (4 weeks), 2 mg per day of Flumazenil (5 days), and 50 mg per day of Hydroxyzine (no days specified).

Conclusions about the Use of Gabapentin for Curing Cannabis-Related Problems

Two studies have explored Gabapentin for alleviating cannabis dependence and both reported successful results. Specifically, Gabapentin was supplied alone (uncombined). More studies are recommended to support Gabapentin's suitability as a treatment for cannabis dependence. As a reference, one of the successful studies also reported a decrease in withdrawal symptoms; further research is also necessary to support Gabapentin's suitability for treating cannabis withdrawal symptoms.

The first successful study used Gabapentin in the range of 300-1200 mg per day (12 weeks) for reducing cannabis dependence and withdrawal symptoms; the second study used a dose of 600 and 1200 mg per day (drug-discrimination task paradigm).

Conclusions

Current results do not support the use of Gabapentin for treating methamphetamine and cannabis dependence; still it is necessary to perform more studies to reach a final consensus. On the other hand, opioids seem to be the only substance revised for which Gabapentin could alleviate dependence problems. Also, further studies should consider testing Gabapentin alone and combined with other pharmaceutical drugs. It is also important to consider the dose and regimen of Gabapentin use to avoid parallel or future problems of Gabapentin misuse or abuse.