THE ETIOLOGY of COVID-19 has not been well-established so far. It has been posited that it developed from bat origin coronaviruses (Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020), but so far this is only a working hypothesis. Yet, long before this particular outbreak, it had been firmly established that so-called "wet markets" in China represented a serious threat of zoonotic respiratory viral infections (Woo, Lau, & Yuen, 2006). Whether or not the current outbreak originated in bats, it is firmly established that the focal point was the city of Wuhan, with its large wet market of wild animal husbandry (Riou & Althus, 2020).

As a whole, international public opinion has disapproved the China's handling for this crisis. The most common accusations are that China's government has been too lenient in the enforcement of sanitary conditions in wet markets, the government was too secretive at the onset of the epidemic, they did not inform the World Health Organization in due time, and its severe restrictions on free speech worked against the optimate flow of information to take meaningful action.

Yet, whether or not China's government was at fault for the spread of the virus, consensus amongst microbiologists and epidemiologists is that COVID-19 was not engineered (Andersen et al, 2020). Yet, this has not stopped conspiracy theorists from claiming otherwise. Muslims, Jews, the Illuminati, Big Pharma, Bill Gates, and a host of other cabals have been accused of engineering COVID-19. As in most conspiracy theories, the purposes of these alleged conspiracies are never sufficiently explained.

But the fact that the virus originated in China, and now the United States is one of the countries most severely affected by the virus, has given prominence to two particular conspiracy theories (Garrett, 2020). Since both countries have had unstable relationships over the last five decades, and more recently, a trade war has intensified, mutual accusations have now come to the front. The United States has accused China of engineering COVID-19 in one of its labs in Wuhan; in turn, China has accused the United States military of using it as a bioweapon.

These conspiracy theories may have a particular political context. But they are now expanding worldwide, even in countries where COVID-19 has not reached high numbers. Social psychologists have long studied conspiracy theories, and have advanced a number of variables that are strongly predictive of a tendency to believe in conspiracy theories.

Psychological Aspects of Conspiracy Theories: Literature Review

Research made visible that lower educational level is strongly predictive of greater adherence to conspiracy theories (Van Prooijen, 2017). Conspiracy theories typically rely more on intuitive approaches, so as thinking becomes more analytical and less intuitive (as it often happens in education), conspiracy theories are harder to accept. Psychologists have documented the so-called "elusive backfire effect", where people abandon conspiracy thinking once they encounter inner incoherence and lack of corroborating data (Wood and Porter, 2019). In conspiracies that relate to medical issues (as COVID-19), this is even more so. Health information campaigns turn out to be successful, and they are effective in correcting the distortions of conspiracy theories (Bode & Vraga, 2018), further confirming the inverse relationship between higher educational levels and adherence to conspiracy theories.

Evidence also suggests that ethnicity is another important variable in predicting how likely subjects will accept conspiracy theories (Ross, Essien, & Torres, 2006). Research shows that conspiracy beliefs are particularly high amongst members of stigmatized minority groups (Davis, Wetherell, & Henry, 2018), as they feel the heat of discrimination more closely. Given that these collectives have had a long history of oppression, they are more likely to invoke new inexistent plots, as in their narrative, these plots are continuation of past oppression.

Perhaps the most powerful predictive factor in conspiracy theories, is the propensity to believe other conspiracy theories (Hagen, 2018). This is explained by the fact that conspiracy theories are usually "monological belief systems", i.e., a series of ideas that are mutually reinforcing. Conspiracy theories attempt to make sense of the world by offering overly simplistic explanations, where everything is related. This monological aspect of conspiracy theories in turn increases the chance that, once people believe one conspiracy theory, they are more likely to believe another.

It is worth noting that, in an important systematic review of literature by Douglas, Sutton and Cichoka (2017), anxiety levels and powerlessness was found to be an important variable affecting the levels of acceptance of conspiracy theories. As a result of the current economic crisis, presumably anxiety levels have risen in the population, although no study has so far been carried out around this variable. However, this invites further investigation, so as to test the hypothesis that increased anxiety levels in Venezuela, may cause greater acceptance of health-related conspiracy theories.

In an important review of the literature and empirical studies, Allington et al (2020) point out the important role that social media play in the spread of conspiracy mongering, especially during the current pandemic. This invites further investigations about whether conspiracy theories about COVID-19 have had wider distribution due to the influence of social media.

In our current times, the role of fake news, and how they spread throughout the population, is also an important factor to consider, when it comes to assessing how successful conspiracy theorists are in divulging their ideas to society at large. In an remarkable study on how concepts of truth are perceived and accepted, Brashier and Marsh (2020) assert that "people exhibit a bias to accept incoming information, because most claims in our environments are true", making it even easier for fake news and conspiracy rumors to spread; furthermore, the authors claim that "people interpret feelings, like ease of processing, as evidence of truth", and "consider whether assertions match facts and source information stored in memory" (p. 1). This is an important insight, as it reflects on the psychological dynamics of how cognitive processes favor particular beliefs, that ultimately, are reflected in acceptance of conspiracy theories, not matter how unlikely or outrageous they may be.

The goal of our research has been to study the social psychology of conspiracy theories, mostly using university students as subjects. Yet, inasmuch as we received notice that there would be a lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and university students would likely not return to courses for the rest of the year, we rushed through, and designed a minor pilot study, as a benchmark for future research. In this pilot design, we studied how widespread are conspiracy theories about COVID-19 amongst Venezuelan students, and how they relate to the variables mentioned above. Venezuela makes an interesting case. In Latin America, Venezuela is one of the countries that has suffered the least from the COVID-19 epidemic. Yet, given the nature of its recent political history, formulations of conspiracy theories in this country have been rampant (Andrade, 2019); inasmuch as the country has been politically polarized since 1999, Venezuelans are more likely to believe in specific conspiracy theories depending on what political party they support. Venezuela has also played a prominent role in the geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China (both powers disputing its sphere of influence in the country; Erikson, 2006), so we anticipated that this particular circumstance would also have some consequence on the willingness to accept COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Method

Participants and Instruments

Venezuela was one of the last countries in Latin America to enforce a lockdown after the World Health Organization. So, a few days prior to the beginning of the lockdown, students from the Faculty of Humanities in University of Zulia, in Maracaibo, Venezuela, were approached to answer a survey, after signing consent forms. The survey was originally in Spanish.

The population size of the School of Humanities is 300 students. With a confidence level of 95% and a margin error of 5%, the sample came out as being 169. The students' ID numbers were randomized, and 169 were chosen to answer the survey. Of these, four declined to answer, so the total sample was made up of 165 students; 80 were male, 85 were female.

A survey was designed asking four fundamental questions, apart from additional information. Using a Likert scale, the survey asked participants to grade on a scale from 1 to 5 their agreement with two statements (1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=undecided; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree). These are the statements: "COVID-19 was engineered by the Chinese government in a Wuhan lab as a biological weapon"; "US Military personnel brought COVID-19 to Wuhan as a biological weapon".

Two additional questions were included in the survey. On the basis of the monological aspect of conspiracy theories, it is important to recall that the best predictor of belief in a conspiracy theory is the belief in any other conspiracy theory. Yet, in a politically polarized country as Venezuela, a further hypothesis can be formulated: belief in a conspiracy theory predicts belief in another conspiracy theory, but only if both theories are politically aligned.

In the Venezuelan political context, support for Nicolas Maduro's government largely entails sympathy for China and opposition to the United States, whereas opposition to Nicolas Maduro's government entails vice versa positions. In Venezuelan public opinion, there are additional conspiracy theories that are largely aligned politically. For example, supporters of Nicolas Maduro are more likely to believe that Simon Bolivar did not die of tuberculosis, but was actually poisoned (this conspiracy theory was popularized by Maduro's predecessor and mentor, Hugo Chavez). Opponents of Nicolas Maduro are more likely to believe that Hugo Chavez died in Havana in December in 2012, and not in Caracas in March 2013, as the official version holds.

Thus, participants were also asked to rate their agreement with these two statements: "Simon Bolivar did not die of tuberculosis, but was poisoned"; "Hugo Chavez died in Havana in December 2012, and his successors lied to the Venezuelan people about it".

Procedure

Research assistants approached participants during the last week of class at the School of Humanities in University of Zulia, before the enforcement of the lockdown. Participants signed consent forms, and were provided with chocolate bars as token of appreciation for their participation. Research assistants read the questions to the participants, and the assistants recorded them on paper as the participants expressed their answers.

The participants were asked demographic information (gender, age, and ethnicity), but their names were not recorded. They were asked permission to include their G.P.A. in the survey (on the basis of 20, as per the Venezuelan educational system) as corroborated in the school administration's record. They were read the instructions regarding the rating of agreement in a Likert scale, and then were read each of the four statements. Each of the interactions were timed, and the mean timing for the whole surveying process was 7,2 minutes.

Results

Venezuela has not traditionally asked for ethnic information in the census, and as a whole, in comparison to other countries, there is little sense of ethnic identity within the population, as most citizens perceive themselves to belong to a racially mixed nation. In the survey, 90 subjects (54%) self-identified either as being mixed or not belonging to any ethnicity; 25 subjects self-identified as belonging to the indigenous Wayuu tribe (15%); 35 subjects self-identified as white (21%), and 15 as Afro-Venezuelans (9%). The mean age for subjects was 20,6, with a standard deviation of 2,6. The mean for G.P.A. was 15,8, with a standard deviation of 3,2.

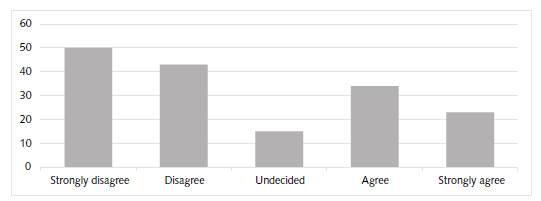

For the statement "COVID-19 was engineered by the Chinese government in a Wuhan lab, as a biological weapon", (Figure 1) 50 subjects strongly disagreed (30%), 43 disagreed (26%), 15 were undecided (9%), 34 agreed (20%), and 23 strongly agreed (14%).

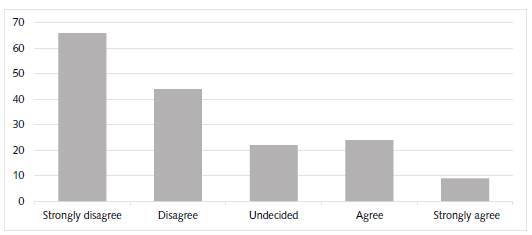

For the statement "US Military personnel brought COVID-19 to Wuhan as a biological weapon", (Figure 2) 66 subjects strongly disagreed (40%), 44 disagreed (27%), 22 were undecided (13%), 24 agreed (15%), and 9 strongly agreed (5%).

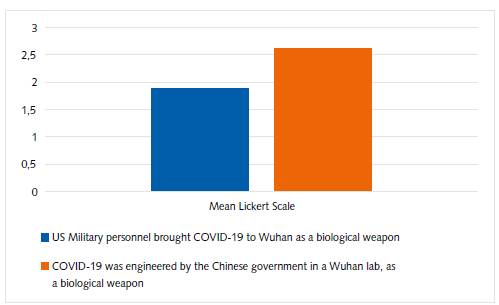

For the statement "US Military personnel brought COVID-19 to Wuhan as a biological weapon", the mean in the Likert scale was 1,89. (the range between strongly disagreeing and disagreeing). For the statement "COVID-19 was engineered by the Chinese government in a Wuhan lab, as a biological weapon", the mean in the Likert scale was 2,61 (Figure 3).

For the statement "Simon Bolivar did not die of tuberculosis, but was poisoned", 44 subjects strongly disagreed (27%), 33 disagreed (20%), 27 were undecided (16%), 26 agreed (16%), and 35 strongly agreed (21%). For the statement "Hugo Chavez died in Havana in December 2012", 38 strongly disagreed (23%), 45 disagreed (27%), 23 were undecided (14%), 32 agreed (19%), and 27 strongly agreed (16%). The mean Likert scale for the statement "Simon Bolivar did not die of tuberculosis, but was poisoned", was 2,84; while the mean Likert scale for the statement "Hugo Chavez died in Havana in December 2012" was 2,78.

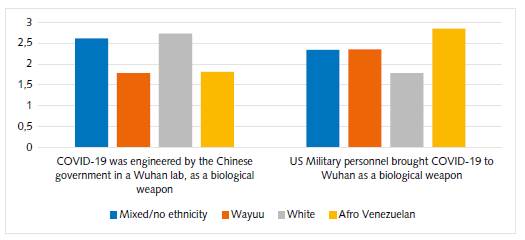

Ethnic groups had different results as well, in the mean Likert scale for each statement. For the statement "COVID-19 was engineered by the Chinese government in a Wuhan lab, as a biological weapon", the mean in Likert scale for each ethnic group is as follows: Mixed/no ethnicity 2,62; Wayuu 1,78; Whites 2,73; Afro-Venezuelans 1,81. For the statement "US Military personnel brought COVID-19 to Wuhan as a biological weapon", the mean in Likert scale for each ethnic group is as follows: Mixed/no ethnicity 2,34; Wayuu 2,35; Whites 1,78; Afro-Venezuelans 2,85.

For the statement "COVID-19 was engineered by the Chinese government in a Wuhan lab, as a biological weapon", the correlation coefficient with GPA was -,35 For the statement "US Military personnel brought COVID-19 to Wuhan as a biological weapon", the correlation coefficient with GPA was -,48.

Discussion and Conclusions

Conspiracy theories regarding COVID-19 are not accepted by the majority of the subjects. Yet, worryingly, given the outrageous nature of the claims, support for these conspiracy theories is still surprisingly high, especially if compared to other medical conspiracy theories (Guidry et al, 2015).

Previous studies have documented that lower educational level predicts the tendency to believe in conspiracy theories (Andrade, 2020). In this research, all subjects had the same educational level (they are all students of the same program), but their achievement was ranked on the basis of GPA. In order to test the hypothetical correlation between keenness to believe conspiracy theories and educational level, we established correlation coefficients between subjects' GPA, and subjects' score along the Likert scale for each of the statements regarding conspiracy theories about COVID-19.

For the conspiracy blaming China for COVID-19, the correlation coefficient was -,35, indicating a negative correlation between academic achievement and proneness to believe this particular conspiracy. For the conspiracy theory blaming the United States for COVID-19, the correlation coefficient was -,48, again indicating a negative correlation between academic achievement and proneness to believe this particular conspiracy. Neither one of these correlation coefficients are particularly strong, but they do suggest that there is a somewhat weak relationship between higher academic achievement and skepticism of conspiracy theories about COVID-19, and that this relationship is stronger for the conspiracy blaming the United States than the conspiracy blaming China.

Another commonly discussed predictive factor in the belief of conspiracy theories is the tendency to believe other conspiracy theories (Goertzel, 1994). This hypothesis was tested in this research, by asking subjects to rate two additional conspiracy theories unrelated to COVID-19, but enshrined in Venezuelan culture. The conspiracy theory about Simon Bolivar's poisoning by American agents was proposed by Hugo Chavez; the conspiracy theory about Chavez's death in Havana was proposed by opponents to Chavez's government. As it turns out, there is a ,86 correlation coefficient between believing that Bolivar was poisoned and the United States engineered COVID-19; while there is a -,75 correlation coefficient between believing that Bolivar was poisoned and China engineered COVID-19. There is a ,83 correlation coefficient between believing that Chavez died in Havana and China engineered COVID-19, while there is a -,73 correlation coefficient between believing Chavez died in Havana and the United States engineered COVID-19. This is a strong indication that proneness to believe in COVID conspiracy theories are predicted by belief in other conspiracy theories, but only if they cohere with particular geopolitical sympathies in the context of Venezuelan politics. Belief in the conspiracy that Bolivar was poisoned suggests sympathies for Chavez's political movement (Aponte-Moreno and Lattig, 2012), and in turn, this implies sympathies for China's role in the world (as China was a big supporter of Chavez's government), and contempt for the United States. Belief in the conspiracy that Chavez died in Havana (and not in Caracas, as the official version states) suggests opposition to Chavez's political movement, and in turn, this implies greater sympathies for the United States (as Chavez confronted the United States throughout his presidency) and greater contempt for China.

As predicted from the onset, belief in these conspiracies have a monological aspect, to the extent that belief in one theory increases the probability of believing in another. However, if the conspiracy theories are not politically aligned, then we formulated the hypothesis that the correlation would be weak. Indeed, this hypothesis was confirmed. There is a -,90 correlation coefficient between believing that China deliberately engineered COVID-19, and believing that the United States deliberately engineered COVID-19. This suggests that for most people, both theories are mutually inconsistent. Yet, the correlation coefficient is not 1 suggesting that when it comes to conspiracy theories, there are some people who hold seemingly contradictory beliefs. This phenomenon has been documented in people who believe at the same time that Princess Diana's death was ordered by the British Crown, and that Princess Diana is alive (Lukic, Zezelj, & Stankovic, 2019), and in the present study, the same phenomenon is marginally observed.

Finally, it has been consistently documented that oppressed and marginalized groups have greater proneness to believe conspiracy theories (Parsons et al., 1999); this is partly explained by the fact that disenfranchised groups ultimately mistrust the establishment, given their precarious conditions, and the actual past instances where minority groups have been targeted for real conspiracies (such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiments targeting African Americans).

This hypothesis is confirmed in the present study. Amongst subjects who self-identified as white, mixed, or without any ethnicity, 28% either agreed or strongly agreed that COVID-19 was engineered by China, and 15% agreed or strongly agreed that COVID-19 was engineered by the United States. By contrast, amongst subjects who self-identified as wayuu or black, 17% agreed that COVID-19 was engineered by China, and 58% agreed that it was engineered by the United States. These results suggest that members of ethnic minorities and oppressed groups have more proneness to believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories, but in the Venezuelan context, they are far more likely to believe conspiracy theories blaming the United States. This finding is not surprising at all, given that oppressed ethnic minorities in Venezuela traditionally rallied around Chavez's government, and as previously explained, sympathies for Chavez's government are somewhat predictive of sympathies for China and contempt for the United States.

Conspiracy theories about medical issues have detrimental effects, as the cases of opposition to vaccinations demonstrate. As of this writing, the consensus amongst researchers is that there is no indication that COVID-19 was engineered, so greater efforts must be pursued to eradicate these irrational beliefs in populations. It has traditionally been thought that education may play a major role in this endeavor. As the results of this research demonstrate, at least in the case of Venezuela, there is some relationship between academic achievement and acceptance of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, but this relationship is weaker than what has traditionally been found in other studies. Consequently, on the basis of the data collected in this study, educational level is not a strong predictor of beliefs in conspiracy theories.

In the Venezuelan context, a far greater predictive factor is ideological positioning in the country's political polarization over the last twenty years, between supporters and opponents of Hugo Chavez, and his successor, Nicolas Maduro. This hypothesis has been confirmed in this study, by establishing higher correlation coefficient between levels of acceptance of particular COVID-19 conspiracy theories, and levels of acceptance of conspiracy theories that are politically aligned with sympathies or opposition to Maduro, and by extension, with sympathies and opposition to either the United States or China.

Likewise, this political polarization in Venezuela has also loosely taken place along ethnic lines, and hence, ethnicity is also a predictive factor in acceptance of COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Consequently, efforts at eradication of COVID-19 conspiracy theories must not focus so much on educational improvement (although that is always welcome), but rather, on depolarization in the political realm, and greater ethnic inclusion in civil life.