THE CONCEPT of empowerment has been adopted in various fields of study, given that it is key for understanding and improving people's lives (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010). However, despite its popularity, there is no consensus on its definition (McWhirter, 1991) and measurement (Mosedale, 2005). One of the reasons for the lack of consensus is the concept refers to power relationships (McWhirter, 1991) in various areas of life (Foucault, 2002) and therefore, its conceptualization and application depend on the people and context from which it is addressed. The lack of consensus makes the concept of empowerment susceptible "to diffuse applications", accentuating the problem of precision (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010, p. 646) and leads to mistakenly confuse it with abuse of power or arrogance (i.e., "power over", domination or subordination; Hollander & Offermann, 1990, p. 179). Riger (1997) claims that although empowerment represents greater power and control, it does not imply dominance as control over people or taking away their resources is not intended.

Despite the difficulties on the conceptualization of empowerment, most authors agree that empowerment is a process (Mechanic, 1991) in which people, organizations, and socially stigmatized, excluded, and marginalized communities gain power and control to make important decisions (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010; Covarrubias, 2018; Kabeer, 2005; McWhirter, 1991; Oxaal & Baden, 1997; Pinderhughes, 1983; Rappaport, 1987; Riger, 1997; Rowlands, 1997a, 1997b; Solomon, 1987). Additionally, many authors agree that empowerment involves change and leads to results. It entails transitioning from the absence of power and control to the exercise of power and control (Freire, 2005; Kabeer, 2005; Martin-Baro, 2006; McWhirter, 1991; Oxaal & Baden, 1997). In this regard, Kabeer (2005) argues that people who have always had options, resources, and possibilities for exercising power and control over their lives have never experienced disempowerment and thus, should not be considered empowered. Based on this perspective, empowerment takes place in contexts characterized by unequal relationships of power (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010), where people and communities have been excluded due to gender, sexual orientation, disability, ethnicity, or economic status, amongst others.

The word empowerment and its derivatives date back to the 17th century. In The Reign of King Charles by Hamon L'Estrange, this word was used as a synonym of authorizing or licensing, while in Paradise Lost by John Milton empowerment referred to the idea of granting power for a specific purpose (Lincoln, Travers, Ackers, & Wilkinson, 2002). However, the concept of empowerment emerged during the 1960s, with the social and political mobilization of the African American population in favor of their civil and human rights. The concept was adopted by social movements (Garcia, 2003) like popular education (Freire, 2005), community psychology (Martin-Baro, 2006; Rappaport, 1987), and feminism (Batliwala, 1997; Sen & Grown, 1987).

The concept of empowerment varies according to the field of study. For instance, for Julian Rappaport (1987), one of the leading exponents of community psychology, empowerment is a process in which people, organizations, and communities gain control over matters important to them. This control provides a psychological sense of personal influence and concern for social impact, political power, and rights. This form of empowerment is a "multilevel" concept covering different contexts of mutual influence. It is a psychological, organizational, political, sociological, economic, and spiritual construct.

Similarly, Stromquist (1995; 1997) argues that empowerment comprises cognitive, psychological, economic, and political elements. The first two elements imply the person identifies and understands the relationship of subordination and develops self-esteem and self-confidence. The economic element is necessary for accessing productive activities that allow financial independence. Finally, the political element refers to the skills needed for promoting social change through social organization and mobilization (Stromquist, 1995; 1997). Likewise, for Kabeer (2005) empowerment involves agency, resources, and accomplishments. With regards to women empowerment, Kabeer (2005) claims it depends on collective solidarity in the public sphere and self-esteem and assertiveness in the private sphere. For Rowlands (1997a; 1997b), empowerment comprises three dimensions: personal, close, and collective relationships. The first dimension refers to the development of the sense of being, individual capabilities, and confidence. The second dimension involves the ability to negotiate in close relationships and internal decisions and, the third one refers to cooperative participation (non-competitive) in local formal or informal political structures.

Other authors, centered on the psychological aspect of empowerment, point out that it is related to various dimensions (e.g., the personality, cognitive, and motivational aspects of self-control, self-esteem, decision making, self-efficacy, and sense of control) and its effects are shown in greater satisfaction and confidence, increased creativity, and autonomy. For McWhirter (1991), empowerment is made up of behavioral and cognitive elements. People need concrete skills to influence their lives and they have to recognize and trust their skills; they need abilities to increase control, autonomy, and social participation for supporting the empowerment process of others. Zimmerman (1995; 2000) in its nomological network presents three components: (1) intrapersonal, referring to personality as the locus of control, and to cognitive factors like self-efficiency and motivational elements of perceived control; (2) interaction, which refers to how people use analytical skills to solve problems and influence their environment, and (3) behavior, related to taking measures to exercise control when participating in community organizations and activities. Consequently, it is expected that empowered people a have higher sense of personal control, a critical awareness of the environment, and the behaviors needed for exercising control (Zimmerman, 1995, 2000). Similarly, Spreitzer (1995) applies the concept to the workplace and proposes a partial nomological network made up of four cognitions: locus of control, self-esteem, access to information, and rewards. In the author's conception, the effects of empowering employees are increased creativity and appropriation of their role at work (Spreitzer, 1995). On the other hand, Oxaal and Baden (1997) claim that empowerment refers to a person's inner power and requires self-confidence, awareness, and assertiveness.

According to the concepts of empowerment mentioned above, there is agreement the concept is multidimensional and involves economic, political, social, and psychological elements. Some definitions agree that assertiveness, self-esteem, and sense of control are part of psychological empowerment and contribute to increasing people's autonomy (Banda & Morales, 2015; McWhirter, 1991; Rappaport, 1987), and although for Spreitzer (1995) autonomy is a dimension of empowerment, the two approaches do not conflict. Both approaches suggest empowerment is a process (Mechanic, 1991) that allows people to increase their autonomy, control, and power while being a constituent part of the construct. Therefore, empowerment is not only a process but also represents a result of a change because it supposes that those who are excluded transition from the absence of power and control to the actual exercise of it (Freire, 2005; Kabeer, 2005; Martin-Baro, 2006; McWhirter, 1991; Oxaal & Baden, 1997). Based on this approach, this study argues that such dimensions (assertiveness, self-esteem, and sense of control) are a manifestation of psychological empowerment, and that empowerment contributes to increasing personal autonomy.

Components of Psychological Empowerment

Assertiveness. Oxaal and Baden (1997) argue that empowerment is related to inner power and implies self-consciousness, self-confidence, and assertiveness. Similarly, from a feminist perspective, Kabeer (2005) claims that women empowerment depends on both, collective support and assertiveness in the private sphere. Flores and Diaz-Loving (2004) claim that assertiveness is the ability to express desires, opinions, personal limitations, positive and negative feelings and defend rights and interests. According to this definition and to Kabeer's (2005) and Oxaal and Baden's (1997) argument, an empowered person is expected to be assertive, capable of expressing feelings, attitudes, desires, and opinions (even if they are unpopular), rejects requests, and defends rights in a direct, firm and honest way, free from anxiety and without undermining the rights of others. Therefore, assertiveness is a clear manifestation of a person's empowerment (or being in the process of empowerment), given that the person is capable of coping with the forces that undermine their freedom and development (Pinderhughes, 1983), and demanding their rights to be respected (Osés, Duarte, & Pinto, 2016).

Assertiveness is related to the socio-cultural context. Thus, it can be expressed directly or indirectly through different forms of expression. In direct assertiveness, a person is capable of expressing her own limitations, feelings, opinions, desires, and rights. In indirect assertiveness, the person lacks the ability for direct confrontations, relies on other means of communication (e.g., letters, telephone), or is not capable at all of communicating feelings (Flores & Diaz-Loving, 2002). Therefore, variables such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, personality, and knowledge influence assertiveness. Some studies associate assertiveness with other psychological factors like locus of control and self-esteem. These studies show that people with a greater inner locus of control are more assertive, compared to people who lean towards an external locus of control. Additionally, the studies find the likelihood of assertiveness is higher for people with high self-esteem (Flores & Cortés, 2014). Based on these findings, it is expected that assertive people are more likely to empower themselves and reach their goals.

Locus of control. Rotter (1966) introduces the concept of locus of control to refer to people's perception about the results of events, either caused by themselves or by external factors. An internal locus of control means a person considers the events are the result of their own behaviors or actions. On the contrary, in an external locus of control, the person considers the events are the result of external factors as luck, destiny, or other elements beyond their control.

As mentioned above, Spreitzer (1995) and Zimmerman (2000) include locus of control as a dimension of psychological empowerment given that it implies having feelings and greater self-control to decide and act on significant matters. Thus, locus of control is important for people seeking greater power and control over their own lives. It allows people to feel more secure when facing adverse situations that limit their decision making and acting. Therefore, the sense of control is key for empowerment. This idea is reinforced by the fact that people with higher income and education feel greater control over their lives, which in turn increases their likelihood of solving problems, compared to those who feel less control (Ross & Mirowsky, 1989).

Self-esteem. Rosenberg (1965) considers that self-esteem is a component of the self-concept and defines it as the set of thoughts and feelings a person has about herself. Kabeer (2005), González, Nuñez, Glez-Pumariega, and García (1997) note that elements like the perception of people around them and social valuation intervene in self-esteem. That is, people are part of the same society and share a system of beliefs and values. If society values people differently based on individual, socioeconomic or cultural characteristics, the social valuation has an impact in the self-concept and therefore, on self-esteem and the value that each person assigns to herself. In this sense, self-esteem is particularly relevant for the process of empowerment. People who have been marginalized could assume less value than those in a dominant or privileged position, as they do not meet the characteristics or standards that are valued in society. The consequences of different valuations are thus reflected on the self-concept and self-esteem. Additionally, Moradi and Risco (2006), based on the decomposition of their model's effects, perceived discrimination, and mental health, identified an indirect association between perceived discrimination and self-esteem. This association was estimated based on the sense of control. People who perceive greater discrimination have less sense of control and self-esteem, as they cannot handle the attitudes of those exercising discrimination.

Autonomy. The definitions of empowerment refer to autonomy, either as a synonym, stage, manifestation, necessary condition, or result. For Stromquist (1997), autonomy is a psychological stage of empowerment, similar to an inner power. Casique (2001) considers that autonomy is part of the empowerment process, while García (2003) believes autonomy is a manifestation of empowerment. Jejeebhoy and Sathar (2001), on the other hand, state that both, empowerment and autonomy, increase control over people's life. Gozálvez-Pérez and Contreras-Pulido (2014) claim that empowerment reinforces a person's autonomy. León (1997) considers that autonomy results from empowerment. Similarly, Cattaneo and Chapman (2010) argue that greater autonomy is the concrete result of empowerment.

Bekker (1993) states that autonomy is a psychological condition derived from the process of individualization and separation. From this perspective, an autonomous person is aware of her opinions, desires, and needs, and is capable of expressing them in social interactions, identifies the opinions and needs of others, shows empathy and has the ability and need for establishing close relationships as well as boundaries, and finally, can handle new situations and reflect her feelings. This concept of autonomy is in accordance with the purpose of empowerment. It leads to a basic and necessary condition for the iterative process that contributes to decision making and acting on matters important for peoples' lives; because, as a matter of fact, the purpose of empowerment is that those who were not able to freely decide and act are able to do so. his freedom of action implies an awareness of opinions, desires, and needs.

Based on all the above, this study centers on the psychological aspect of empowerment and draws elements from the different concepts discussed so far. Psychological empowerment is therefore defined in this study as a result and non-observable construct that predicts autonomy (Banda & Morales, 2015; Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010; León, 1997; McWhirter, 1991; Rappaport, 1987), and comprises assertiveness (Kabeer, 2005; Oxaal & Baden, 1997), self-esteem (Banda & Morales, 2015; Kabeer, 2005), and sense of control (Zimmerman, 1995, 2000).

he goal of the study is to assess this theoretical argument based on a structural equation model. According to empirical evidence, the three dimensions should be capable of measuring psychological empowerment and should be positively associated with it. Additionally, it is expected a negative relationship between indirect assertiveness and non-assertiveness. Finally, the construct should predict autonomy. It is also intended to identify if there is a difference in the psychological characteristics between women and men, as well as in the model since the feminist literature considers that there is a relationship of subordination between both sexes due to sociocultural factors.

Hypothetical Model

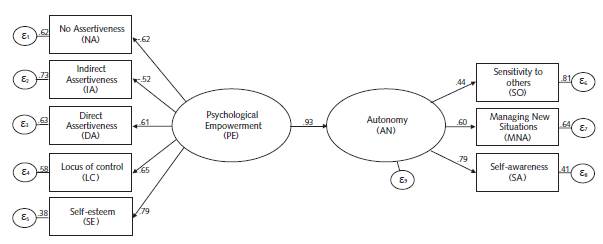

The model is comprised of two models: a measurement and a structural model. The first model aims at measuring psychological empowerment (latent variable) through three indicators (observable variables). In the structural model, psychological empowerment predicts autonomy.

Note: The rectangles show the manifest variables (y 1 , y 2 , […], y8) and the ellipses the latent variables (η 1 and η 2 ). Each indicator is associated with an error variance (ε). The values in the arrows are the factorial loads (λ).

Figure 1. Psychological Empowerment Model

Method

Design and Participants

This is a cross-sectional and correlational study that uses secondary data. A non-probabilistic sample was used. The analytical sample comprises 1,569 participants from five Mexican States (Mexico City (19%), Coahuila (18%), Michoacán (19%), Guanajuato (21%), and Yucatán (23%). The participants in the sample have complete information; 56% are women; the average age is 29 years (SD=12 years); 59% hold college degrees, 30% are married or live in free union, and 41% are employed.

Instruments

The following instruments were used to carry out the research: (1) Multidimensional Assertive-ness Scale (EMA) by Flores and Diaz-Loving (2004), (2) Locus of Control Scale by Rotter (1966), (3) Self-esteem Scale by Rosenberg (1965), adapted by Martín-Albo, Núñez, Navarro and Grijalvo (2007), and (4) Autonomy Scale ACS-30 (reduced version 18 reagents). Each psychological scale has a Likert-type scale format ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The scales have been assessed and validated and, given the satisfactory results of the assessment, the study is based on these scales. Below is a brief description of each.

Multidimensional Assertiveness Scale. The multidimensional Assertiveness Scale (EMA) by Flores and Diaz-Loving (2004) consists of 45 pictographic Likert-type affirmations of five response options and is made up of three dimensions: (1) Assertiveness, the ability to express your limitations, feelings, opinions, desires, and rights, amongst others (α=.8o), (2) Indirect Assertiveness, the inability to directly express and confront limitations, feelings, opinions, desires, and rights, amongst others. Telephone, messages, and letters are some examples of means of communication used in this case. (α =.92), and (3) Non-assertiveness, the inability to express and directly face limitations, feelings, opinions desires, and rights, amongst others (α =.85).

Locus of Control Scale. The Locus of Control Scale by Rotter (1966) is based on people's opinion about the degree of control they exercise in their life. The scale is made up of two dimensions: the internal, founded on the belief that results are determined by behavior; and the external, based on the belief that results are the product of luck or destiny. The scale consists of eight reagents. Each reagent is divided into two dimensions, internal locus "I am responsible for my own accomplishments", and external locus "The good things that happen to me are pure luck" depending on the reasons behind the results (Visdómine-Lozano & Luciano, 2006). The internal consistency is .68.

Self-esteem Scale. The self-esteem Scale by Rosenberg (RSES) has been translated and adapted by Martín-Albo et al. (2007) following transcultural translation procedures. The scale is a one-dimensional instrument based on a phenomenological concept of self-esteem that captures a person's global perception of herself. It comprises 10 reagents of self-esteem and self-acceptance. The values of internal consistency (α=.85-.88) and correlation test-retest (.84) support the reliability of the scale (Martín-Albo et al., 2007). The results confirm the one-dimensional structure of the RSES. Regarding construct validity, the results show a high and significant positive correlation with the five dimensions of the self-concept. This result is in line with the approach of considering self-esteem as an evaluative conceptual level of self-concept (Shavelson, Hubner, & Stanton, 1976).

Autonomy Scale. Originally, 30 elements comprise the Autonomy Scale ACS-30 (Bekker, 1993; Bekker & van Assen, 2006). However, based on a confirmatory factorial analysis, we opted to eliminate one reagent with inadequate translation. The scale measures three dimensions: (1) Self-awareness, "Often, I do not know what is my opinion", "Usually, I am clear on what I like best"; (2) Managing new situations, "I quickly feel comfortable in new situations", "I need a long time to get used to new situations", and (3) Sensitivity to others, "I often wonder what others think of me". The internal consistency of each dimension is 0.81, 0.82, and 0.83, respectively (Bekker & van Assen, 2006).

Procedure

We applied the instrument to the Mexican population and collected psychological and socio-demographic information using self-application. Participation was voluntary and anonymous (without any type of economic remuneration). Answering the instrument took an hour, on average. It was answered on paper (using pencils) and in public places.

Results

To determine if there is a relationship between empowerment and autonomy we used descriptive statistics and generated and evaluated a theoretical model for testing the relationship using structural equations. Table 1 shows the psychometric properties of the main variables in the study. Specifically, we present the average, standard deviation, coefficient of internal consistency, range (potential and actual), and skewness. The coefficients of the four scales and their dimensions show good reliability, except for the dimension "sensitivity to others" (α=.53) of the Autonomy Scale. Table 2 shows the correlations of the scales, all of which are significant. There is a direct and strong correlation between self-esteem and autonomy, which is also observed between autonomy and assertiveness and locus of control. On the other hand, the correlation of indirect assertiveness and non-assertiveness with autonomy is negative. The statistical differences between women and men are presented in Table 3. According to the results, there are no statistical differences in "indirect assertiveness", "managing new situations" and "sensitivity to others". The statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package STATA 14. The structural equation model (SEM) is characterized for having a measurement model, that represents the relationships of the latent variables (or constructs) with their respective indicators (observable variables), and a structural model that describes the hypothetical causal relationships between the proposed constructs (i.e., empowerment and autonomy).

Table 1 Psychometric Properties of the Main Variables of the Study

| Range | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | m | SD | α | Potential | Real | Sk |

| Empowerment | ||||||

| Assertiveness | 2.44 | .89 | .75 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | 0.23 |

| Indirect assertiveness | 4.08 | .63 | .82 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | -0.85 |

| Non-assertiveness | 2.48 | .82 | .77 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | 0.23 |

| Self-esteem | 4.04 | .65 | .84 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | -0.86 |

| Locus of control | 3.95 | .62 | .72 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | -0.51 |

| Autonomy | ||||||

| Sensitivity to others | 2.90 | .81 | .53 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | -0.04 |

| Managing new situations. | 2.60 | .64 | .63 | 1-5 | 1.0-5.0 | 0.10 |

| Self-awareness | 2.23 | .66 | .71 | 1-5 | 1.0-4.8 | 0.30 |

Table 2 Correlations for the Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empowerment | ||||||||

| 1. Non-assertiveness | - | |||||||

| 2. Indirect assertiveness | .45 | - | ||||||

| 3. Assertiveness | -.39 | -.29 | - | |||||

| 4. Locus of control | -.36 | -.32 | .41 | - | ||||

| 5. Self-esteem | -.44 | -.34 | .49 | .56 | - | |||

| Autonomy | ||||||||

| 8. Sensitivity to others | .26 | .28 | -.17 | -.27 | -.33 | - | ||

| 7. Managing new situations. | .44 | .31 | -.37 | -.31 | -.42 | .27 | - | |

| 6. Self-Awareness | .42 | .38 | -.45 | -.45 | -.59 | .34 | .45 | - |

Note: All coefficients are significant at p<.01

Table 3 Psychological Attribute Scores between Gender

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | m | SD | m | SD | DIFF. | t(1567) | p | CohensD |

| Empowerment | ||||||||

| Non-assertiveness | 2.41 | .83 | 2.56 | .80 | -.14 | -3.37 | .001 | -.17 |

| Indirect assertiveness | 2.44 | .92 | 2.44 | .85 | .00 | 0.04 | .970 | .00 |

| Assertiveness | 4.17 | .58 | 3.96 | .67 | .21 | 6.77 | .000 | .34 |

| Locus of control | 3.99 | .59 | 3.89 | .65 | .10 | 3.17 | .001 | .16 |

| Self-esteem | 4.07 | .67 | 3.99 | .63 | .09 | 2.65 | .008 | .14 |

| Autonomy | ||||||||

| Sensitivity to others | 2.93 | .84 | 2.86 | .77 | .08 | 1.87 | .061 | .10 |

| Managing new situations. | 2.62 | .65 | 2.57 | .61 | .06 | 1.70 | .090 | .09 |

| Self-Awareness | 2.18 | .67 | 2.28 | .64 | -.10 | -2.92 | .004 | -.15 |

Due to the fact that the sample size is relatively large, the model parameters are estimated using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method. This method provides consistent, efficient, and unbiased estimates with sufficient sample sizes that facilitate the convergence of estimates with parameters, even in the absence of normality although, it should be noted that the data used in the study does not present significant biases (Table 1). The model's goodness of fit is assessed based on the x2, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and General Goodness of Fit Index (GFI). It is important to mention there is some consensus a model has a good fit when the RMSEA is less than .05 (good) or .08 (satisfactory), and the CFI and GFI are above .90 (Kerlinger, Lee, Pineda & Mora Magaña, 2002). Although the adjustment indicators are acceptable (RMSEA=.07, SRMR=.04, CFI=.94, and GFI=.94), the Chi-square indicator shows the covariance matrix is not reproduced with the sample data thus the model does not present a good fit (Figure 2). The adjustment indicators of the model in the sample of women are similar to the values obtained in the model of men as well as the variability explained.

Note: The rectangles show the manifest variables and the ellipses the latent variables. Each indicator is associated with an error variance (E). The values in the arrows are the factorial loads. Standardized parameters. On the model fit x2 SB(19 n=1569)=182.4, p= .001, cn= .94, TLI= .92, RMSEA= .07, SRMR= .04. All parameters are statistically significant p<.001. The maximum likelihood was estimated with the robust Santorra-Betler correction (SB).

Figure 2 Model of Psychological Empowerment

The estimation results are shown in standardized measures for both, the general model (Figure 2) and for women and men (Annex 1). The latter estimates aim at identifying differences in the effect of empowerment on autonomy. The empowerment measurement model consists of five indicators: self-esteem (.79), locus of control (.65), direct assertiveness, indirect assertiveness, and non-assertiveness (.61, -.52 y -.62 respectively). The negative sign associated with the coefficients shows that people with psychological empowerment present these characteristics to a lesser extent or do not present them. In comparison, attributes with positive signs reflect psychological empowerment. he interpretation for the disturbance associated with the indicators of the general model, no assertiveness, indirect assertiveness, direct assertiveness, locus of control, and self-esteem is 62%, 73%, 63%, 58%, and 38% respectively. Consequently, the variability is explained in 38%, 27%, 37%, 42%, and 62% same order.

he structural model was created to examine the hypothetical causal relationship between empowerment and autonomy. The result provides evidence of such hypothetical causal relationship (.93) raised by Banda and Morales, (2015), Cattaneo and Chapman (2010), Leon, (1997), McWhirter (1991), and Rappaport (1987). These authors suggest autonomy is a concrete result achieved by people who have become empowered.

Discussion

Based on the analytical framework, it is important to highlight that empowerment has provided concrete evidence of its potential. For instance, the effect of women's empowerment on health has been measured and according to the results, women with power have greater access to maternal care (76%) and use contraceptives more often (66.6%), leading to lower neonatal mortality (36%). In contrast, less empowered women have less access to maternal services (72%), less contraceptive use (44%), and relatively higher neonatal mortality (43%) (Chaturvedi, Singh, & Rai, 2016). Similarly, relationships between empowerment and low rates of unwanted pregnancies, and longer birth intervals have been found (Upadhyay et al., 2014).

These empirical contributions show the explanatory power of psychological empowerment and how it is reflected in autonomy. Additionally, they provide evidence for developing initiatives aimed at improving quality of life, especially of people in vulnerable conditions or susceptible to discrimination. Although empowerment has been used in different fields of study, empirical research is scarce due to its complexity for operationalization (Mosedale, 2005). For this reason, we use a structural equations model that allows estimating hypothetical constructs that are not observed directly. Hence, the theoretical model is a fundamental element for guiding the estimation process and explaining the observed reality in each relationship.

The proposed model started from the idea that psychological attributes as assertiveness, self-control, and self-esteem are part of psychological empowerment, facilitating the transition towards greater autonomy. hat is, people who are in contexts of subordination and have relatively high self-esteem, sense of control, and assertiveness, will handle adverse circumstances more easily and have an easier path towards greater autonomy. It is important to highlight, however, that it is still necessary to eliminate environmental barriers that produce inequality and dependency, which have negative socioeconomic and psychological impacts (Haushofer & Fehr, 2014).

Based on the estimations results, self-esteem, locus of control, and assertiveness are part of psychological empowerment (bAE=.79, bLC=.65, b =.61, standardized coefficients). The positive relationship is consistent with what was expected, suggesting that self-esteem, sense of control, and assertiveness contribute to increasing people's security and ability to express themselves. his is consistent with Kabeer's (2005) argument that empowerment is linked to self-esteem and as-sertiveness. Additionally, these characteristics taken together contribute to increasing people's willingness for solving problems, making decisions, and exercising greater control over their lives, as proposed by Jejeebhoy and Sathar (2001). These indicators show that self-esteem, locus of control, and assertiveness are characteristics that favor the development of psychological empowerment and increase people's abilities for handling adverse situations.

Also, the non-assertiveness and indirect assertiveness dimensions are included in the model. he results are in line with the proposed hypothesis, both are negatively and strongly associated with psychological empowerment (b =-.62, b =-.52, standardized coefficients) confirming that non-assertiveness and indirect assertiveness are elements contrary to psychological empowerment. This finding suggests that less assertive people have less empowerment and would have greater difficulty facing obstacles that entail limited decision making and control. In other words, these characteristics can obstruct the path to greater autonomy, as lack of assertiveness means the person is not capable of expressing a desire and therefore, she is a function of situations or people. In addition, we observe that of the three dimensions that compose autonomy (latent variable), self-awareness and managing new situations present high positive values (bAC=.79, bMNS=.60, standardized coefficients). Thus, it is expected that people with broad self-awareness and those who can identify their preferences, interests, and desires have greater clarity for decision making. Similarly, people with a greater ability to handle new situations are expected to adapt better to new scenarios, to start new activities easier, to be more likely to face new challenges and solve problems, and to have a greater probability of deciding and acting under different circumstances, leading to greater autonomy. herefore, a higher level of self-awareness and better managing new situations shows greater autonomy. he dimension "sensitivity to others" shows a positive and low relationship with autonomy (bSO =.44, standardized coefficient), which is consistent with the fact that high sensitivity to others could be an indication of increased dependency or decreased autonomy.

According to the theoretical model and based on its goodness of fit, the results are consistent with empirical data, as expected. he latent variable of psychological empowerment predicts autonomy (bEPAN =.93) and is in line with Cattaneo and Chapman (2010), Garcia (2003), Leon (1997), and Gozalvez-Perez and Contreras-Pulido (2014) who claim that autonomy is a concrete result of empowerment. herefore, a person with self-esteem, sense of control, and assertiveness is showing psychological empowerment and consequently, has greater autonomy. These results are similar in the estimation of the model between women and men. However, it is observed that the effect of psychological empowerment on autonomy is greater in the woman model. his result could be due to differences in attributes since women presented higher scores in assertiveness, locus of control and self-esteem than men did.

In addition, the results obtained are in line with the approach of Gozalvez-Perez and Contreras-Pulido (2014) in the sense that the term "empower" means reinforcing the critical autonomy of people. Under this analytical framework, autonomy is understood as a result of empowerment. his approach is strengthened with Leon's (1997) claim that empowerment leads to personal autonomy, that is, empowered people tend to be autonomous. herefore, it can be stated that autonomy is a concrete result of empowerment, as proposed by Cattaneo and Chapman (2010) who argue that empowerment could lead to greater autonomy. Similarly, Bekker (1993) considers that autonomy is a psychological condition. In Bekker's approach, empowerment could be a factor influencing autonomy, given that people would be aware of their own opinions or desires and would express them in an assertive way. Additionally, people would be sensitive or empathic to the needs of others and would show their ability to handle new situations. According to this idea, if empowerment is triggered by a situation of subordination, once people move to a different situation through the empowerment process, they would be able to recognize and handle new circumstances, consolidate the process and ultimately, achieve better results.

In summary, the study provides evidence on the construct of empowerment and autonomy and makes theoretical contributions based on the data. This is relevant in the sense that provides new evidence to continue studying the construct, which is important given people's need for moving towards a scenario where discrimination and subordination are not the prevailing elements. The new scenario should be adequate for generating self-consciousness, allow people to be critical of the environment, more participatory and influential, and therefore, should contribute to phycological freedom as proposed by social psychology.

Limitations

The study is based on secondary data (i.e., it was not collected for the study's purpose) that prevented including variables as discrimination, income, and other psychological scales. Additionally, the data is cross-sectional and limits the analysis to a certain time ruling out the possibility of studying the process of psychological empowerment. Furthermore, as data from a general population was used, it was not possible to carry out cotextualized research to assess psychological empowerment in a vulnerable or discriminated population.

Conclusions

We conclude there are some characteristics that contribute to and reflect phycological empowerment, that allow people to be more autonomous. However, the model of psychological empowerment proposed in this study must be replicated in a vulnerable population or that experiences discrimination to prove the relationships that the different authors have proposed. Likewise, other structural elements must be considered in the empowerment of people. As explained by Ross and Mirowsky (1989), income and education contribute to an increasing sense of control, and thus, is important to work on these external elements that contribute to assertiveness and improve people's self-esteem. Public policies that seek to contribute to people's empowerment should not only consider economic factors but also psychological ones. For instance, monetary transfers that do not take into consideration factors like discrimination, violence, differences in power within the household, and their impact on mental health and decision making will hardly give the expected result. Additionally, empowerment should continue to be studied in a differentiated and contextualized way to locate the possible causes of such differences found in this study.