DATING VIOLENCE (DV) consists of the execution of intentional acts of physical, psychological or sexual aggression, which occur in couples who do not live together or have children. This is why it is considered a form of partner violence that usually occurs between adolescents and young people, unlike marital violence, that occurs between people who have a marital bond (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2019; Niolon et al., 2015; Rubio-Garay et al., 2017).

The high figures reported in several studies carried out in recent years on the prevalence of violence acts perpetrated by adolescents with their partner, or of which they have been victims in dating relationships, have led to consider this phenomenon as a public health problem (Ludin et al., 2018; Mercy & Tharp, 2015; Peterson et al., 2018; Temple et al., 2013; Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2019; Wincentak et al., 2017). These figures reveal that psychological, physical and / or sexual abuse often occur in adolescent dating relationships, that increases with age and in which adolescents participate both as victims and perpetrators (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017; Ybarra et al., 2016).

A systematic review conducted with 101 prevalence studies of physical and sexual DV, published between 1980 and 2013 and carried out mainly in the United States with adolescents from 13 to 18 years old (Wincentak et al., 2017), found that between 1 % and 61 % of the participants had perpetrated or had been subjected to physical violence, and that between a little less than 1 % and 54 % had been victim of sexual violence, with higher rates among older adolescents.

Another systematic review that included a total of 113 studies published up to 2013 on the prevalence of physical, psychological and sexual DV, both perpetrated and received, in adolescents and young adults (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017), found that in these studies, between 8.5 % and 95.5 % of the participants reported having been subjected to psychological violence; between 0.4% and 57.3 % , to physical violence, and between 0.1% and 64.6 %, to sexual violence, while between 4.2 % and 97 % of the participants reported having inflicted psychological violence; between 3.8 % and 41.9 %, physical violence, and between 1.2 % and 58.8 %, sexual violence.

Most of the studies selected in this review were conducted in the United States, six in Spain and one in other countries (Canada, Thailand, Colombia, Finland, Chile, Sweden, Mexico, and Portugal). However, the authors did not observe a high variability between the prevalence figures reported in these countries, indicating that this phenomenon affects a significant number of adolescents and young people worldwide (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017).

The high variability in the prevalence figures found in these two reviews shows differences between one study and another with respect to what is understood by DV, the measurement instrument used and the characteristics and size of the samples under study (Rey, 2008; Wincentak et al., 2017). Thus, Rubio-Garay et al. (2017), highlight how the figures tended to be higher when the studies used the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) and later versions of it (MCTS and CTS2), or the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI), whereas Wincentak et al. (2017) observed lower rates among the studies that used a single item instrument, as opposed to those that applied questionnaires with multiple items.

Prevalence studies also show important differences by sex in terms of the types of violence perpetrated and suffered. In relation to sexual violence, these studies show generally that a greater proportion of women are victims of sexual violence, while more men exert this type of violence (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017; Wincentak et al., 2017; Niolon et al., 2015; Ybarra et al., 2016). Regarding psychological violence, research tends to show that more women perform this type of violence, although they also suffer it in a greater proportion than men (Niolon et al., 2015; Reed et al., 2017; Rubio- Garay et al., 2017).

Finally, regarding physical violence, the results of the review carried out by Wincentak et al. (2017), indicate, in general, higher rates of women perpetrators of this form of violence. Thus, for example, in a sample consisting of 1058 American students from 14 to 21 years old, it was found that a significantly higher proportion of women had practiced physical and psychological DV, but also that they had suffered this last type of violence in a greater proportion than men (Ybarra et al., 2016); while in a sample of 1,673 students from sixth to eighth grade from high-risk urban American communities, a higher proportion of women_reported having engaged in threatening behavior, verbal / emotional abuse and physical violence, while men reported a higher probability of sexual violence (Niolon et al., 2015).

Evidence indicates, on the other hand, that the different types of DV are not presented in isolation but jointly (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017). Thus, for example, in the aforementioned research by Ybarra et al. (2016), a high percentage of the participants reported both victimization and perpetration, along with different types of DV over time. For their part, Karsberg et al. (2018) found, in a sample of 2934 Danish seventh grade students, that 20 % of them had suffered and had also perpetrated, at least one of the three types of DV being assessed (emotional, physical and sexual). Likewise, they found that 14.3 % of the participants had suffered two or three types of DV and that 6 % had perpetrated the same number of types of DV, with a significantly greater number of men perpetrating those types of violence.

In Latin America, some studies on the prevalence of dating violence have been carried out in institutions of secondary and higher education, in countries as Mexico (Cortés-Ayala et al., 2015; Zamora-Damián et al., 2018), Chile (Vivanco et al., 2015), and Argentina (Arbach et al., 2015).

In Colombia, in particular, there are only regional studies that report high figures about this problem, with statistics on different types of violence received and inflicted, similar to those of studies carried out in other countries. In a sample consisting of 403 university students from the city of Tunja, aged between 15 and 30 years, it was found, through the Checklist of Experiences of Abuse in the Couple, that 81.1 % had been subjected to at least one psychological violent behavior; 31.5 %, to some emotional violent conduct; 22.4 % to some physical violence action, 18.2 % to some way of economic violence, and 8.3 % to a sexual violence act, reporting that a significantly higher proportion of men had performed a behavior of economic violence (Rey, 2009).

For their part, Martinez et al. (2016) carried out a study using the same instrument, where 589 high school students from the same city, aged between 12 and 22 years participated, finding that 61 % of them had been subjected to at least one emotional violence behavior, 51.4 % to some psychological violence action, 50.9 % to some physical violence act, 29.5 % to some form of economic violence, and 26.3 % to a sexual violence behavior. No statistically significant differences by sex were found. Unlike the previous study, whose participants had a wider age range, a much higher prevalence of physical and sexual violence was found in this study, although less psychological violence.

In another sample made up of 902 university students from the same city, aged between 15 and 35 years old, it was found that 83.3 % had inflicted at least one psychological violence behavior, 40.1% some physical violence conduct, 37, 6 % an emotional violence behavior, 22.8 % some form of sexual violence, 14.9 % a behavior considered negligent, and 11.2 %, an act of economic violence (Rey, 2013). A significantly higher percentage of men reported at least emotional, sexual, economic, and negligent violence.

Another study conducted with 237 university students, aged between 16 and 28 years, residents of the city of Bucaramanga, using the Spanish version of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI; Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006), found that 94.9 % of the participants had perpetrated verbal violence, 34.7 %, relational violence, and 22 %, physical violence, but there were no statistically significant differences by sex (Redondo et al., 2017). Likewise, 91.9 % of the participants had been the target of verbal violence, 45.3 % had been victims of relational violence, and 17.8 %, of physical violence.

Although the results of these studies are consistent with those carried out in other countries, which indicates that the prevalence of psychological violence is greater than the physical and sexual violence, their results seem to depend on the instrument used, the type of violence examined and the age of the participants. Therefore, it is not possible to make the necessary comparisons to estimate the magnitude of this problem in the country. There are also no published data from other regions of Colombia, particularly from Bogotá-its capital and the most populated city- and the way in which the different types of DV occur at the same time, as has been verified in previous studies carried out in other contexts (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017; Karsberg, et al., 2018; Ybarra et al., 2016).

Conducting prevalence studies with larger samples also allow to recognize the magnitude of the phenomenon in Colombia, promoting the development of research aimed at validating assessment tools of this phenomenon and alternative prevention, case identification and intervention of victims and perpetrators, in educational and community settings, thus preventing the physical and mental health difficulties associated with this form of violence and its continuation in adult life (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017; Temple et al., 2013; Wincentak et al., 2017).

In addition to prevalence, understood in the context of DV as the percentage of people in a population or sample who report having perpetrated or received this form of violence, the importance of examining other dimensions of abusive behavior has been highlighted, as frequency and the severity (Follingstad et al., 1999). The frequency, understood as the number of times that a person reports having exercised and / or suffered these behaviors, has been used to examine the differences by sex and the relationship that exists between the different types of DV, constituting another way to assess the magnitude of this phenomenon that complements the prevalence (Olsen et al., 2020). Taylor and Xia (2020), for example, found a high prevalence of DV, although with low frequencies, among 131 American adolescents living in rural areas.

The above leads to the formulation of the following research question: What is the prevalence and frequency of perpetration and victimization of different types of DV among adolescents in Bogotá and other cities in Colombia? In accordance with the foregoing, this study aimed to examine the prevalence and frequency of perpetration and victimization of different types of DV, among adolescents from 13 to 19 years of age in five capital cities of Colombia, making comparisons by sex. The relationship between the number of types of violence inflicted and received and the different types of violence perpetrated and suffered was also analyzed.

Method

Participants

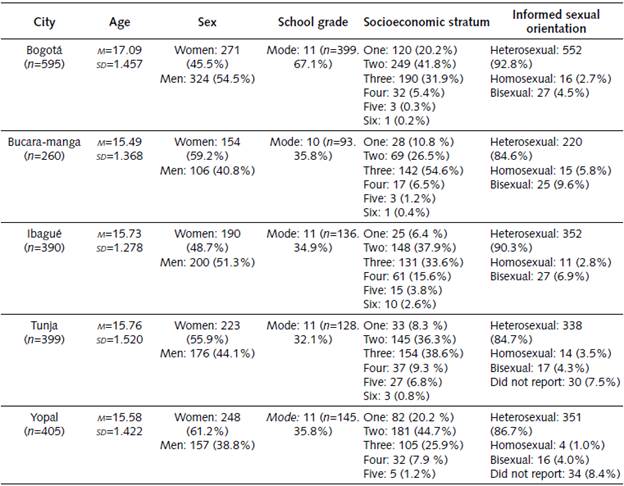

Participants were 2049 adolescents aged between 13 and 19 years (M = 16.07; DS = 1.6), 1086 women (53%) and 963 men (47%), linked to educational institutions selected according to their availability in the cities of Bogotá, Bucaramanga, Ibagué, Tunja, and Yopal, and who were enrolled from third to eleventh school grades. Most of these students were in eleventh grade (n = 876, 42.8 %, which corresponded to the mode), and lower percentages were in tenth (n = 550, 26.8 %), ninth (n = 383, 18.7 %), and eighth (n = 203, 9.9 %) grades.

On average, these adolescents reported having had 3.78 couple relationships, of which the current relationship had lasted an average of 6.20 months and the previous one, 7.30 months. 88.5 % mentioned being heterosexual, while 2.9 % indicated being homosexual, and 5.5 %, bisexual (3.1 % did not report their sexual orientation). According to the classification of socioeconomic strata of the National Administrative Department of Statistics, 14.1 % of participants lived in the low-low socioeconomic sector, 38.7% in the low segment, 35.2 % in the medium-low, 8.7 % in the medium, 2.6 % in the - medium-high, and 0.7 % in the high stratum. Table 1 presents these characteristics, ordered by city.

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants by City.

Note. n: sample size; n: subsample size; M: mean; SD: standard deviation. The frequencies and percentages of sex, socioeconomic stratum, and informed sexual orientation are presented.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) having had or having a romantic relationship of at least one month duration, (b) being between 13 and 19 years old, an age range that falls within the adolescence period, according to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2017), (c) being single, and (d) having the parents' consent and the adolescents' assent (except the ones over 18). Participants were selected through non-random sampling, according to their availability in the participating institutions.

The cities were selected according to the following reasons: (a) Bogotá is the capital of Colombia and the most populous city in the country, therefore it groups together citizens from different regions; (b) the cities of Bucaramanga, Ibagué, and Tunja are located in the Andean region of Colombia, but they represent regions with certain cultural differences, as occurs with other intermediate cities of the country, and (c) the city of Yopal, is located in the Orinoquia region of the country, so it was expected to represent that Colombian region.

Instrument

Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory, Spanish version (cadri, Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006). This instrument was designed for adolescents and allows recording the execution of physical (4 items), verbal-emotional (10 items), relational (3 items), sexual violence acts (4 items), and threats (4 items) towards the actual or prior partner in the last 12 months, as well as behaviors of the same type that their partner perpetrated on them in that period, through 25 pairs of items that are answered in a Likert scale with five response options: "Never" (0), "Rarely" (1), "Sometimes" (2), and "Often" (3) (Wolfe et al., 2001). It includes another 20 items that show an adequate solution to the couple's conflicts that were not taken into account in this investigation to reduce the duration in the application of the instruments.

The types of violence examined by the instrument includes abusive behaviors as: (a) physical: throwing something, kicking or pushing; (b) verbal-emotional: ridiculing, insulting, blaming, bringing up the past, and attempting to promote jealousy or anger; (c) relational: rumor spreading and other efforts directed at a partner's peer group; (d) sexual: forcing kisses, touches, and sexual intercourse, and (e) threatening behaviors of hit, hurt or destroy valued something. These types make up the components of the sub-scales of perpetration and victimization (Wolfe et al., 2001).

The authors of the CADRI Spanish version (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006), found that the original five components explained 50 % and 51 % of the variance in the items of aggression perpetrated and suffered, respectively. Regarding reliability, they found alphas that ranged from .53 to .78, with an α = 0.85 for all items of aggression perpetrated, and 0.51 to 0.79, with an a = 0.86 for all items of aggression received.

This instrument was validated with the participants in this study, including nine 12-year-old participants (n = 2058), implementing a confirmatory factor analysis taking into account the sub-scales and its components, according to Wolfe et al. (2001) and Fernández-Fuertes et al. (2006). Good fit indices were obtained: AGFI = .903 (.90-1.00); GFI = .913 (.90-.95), and RMSEA = .015 (0-.05), as well as the following alpha values in the components of the assaults perpetrated and suffered respectively: (a) physical: .75/.74; (b) verbal-emotional: .83/.83; (c) relational: .74/.73; (d) sexual: .73/.56; (e) threats: .72/.69, and (f) all items: .73/.84, values similar to those reported by the Spanish researchers (Redondo-Pacheco et al., 2021).

The CADRI was selected from among other instruments, not only because it has a version in Spanish, but because it includes behaviors of intimate partner violence that are more common among adolescents than among adults and married people (Wolfe et al, 2001). Besides, the instrument allows examine both perpetration and victimization, aspects of interest for this study, being widely used internationally, including in Colombia (Redondo-Pacheco et al., 2021).

Self-report questionnaire of psychological variables (Rey, 2012). It allows obtaining sociodemographic information and about different socio-family circumstances and health risk behaviors. It was used in this work for the sociodemographic characterization of the participants.

Procedure

The study was approved by the ethics committee of each of the institutions in which the researchers were linked, that examined fulfillment with the ethical standards of the case. Authorization for selecting the participants in the aforementioned institutions was requested, subsequently proceeding to contact them in their classroom and explain to them the research's objective, its inclusion criteria, procedure and ethical considerations. Interested students who met the inclusion criteria were given an informed consent form to sign together with their parents, containing the same information provided to the teenagers. The instruments were administered in a group manner to the students who submitted the mentioned form signed by them and their parents.

The data obtained was incorporated into a SPSS version 22.0 database, that was reviewed and refined, initially carrying out comparative descriptive analyzes of the number of participants by sex who reported, at least "rarely", having inflicted and / or suffered any of the DV behaviors that appear in the CADRI (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006), at a general level and according to the type of violence reported.

These analyses were carried out per each city and generally. Subsequently, the frequency of perpetuation and victimization of each of these types of violence was compared by sex and at a general level, as well as the number of types of violence inflicted and received (measured with the CADRI, Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006), by means of the Student's f-test and the Cohen's d test. The effect sizes located between 0.2 and 0.3 were estimated as small, those located around 0.5 as medium, and the ones equal to or greater than 0.8 as large (Cohen, 1988).

These differences were confirmed through the multivariate analysis of the unidirectional variance (unidirectional MANOVA), taking the different types of violence perpetrated and received as dependent variables, calculating the size of the effect with the ETA partial squared (partial цг), estimating it as small if it was around 0.01, medium if it was around 0.06, and great if it was greater than 0.14 (Cohen, 1988).

Then, we examined the correlations between all the types of violence analyzed and the total number of types of violence perpetrated and received using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The correlations between -0.3 and -0.1 and between 0.1 and 0.3 were considered weak; the correlations between -0.5 and -0.3 and between 0.3 and 0.5 were considered moderate; and those between -1.0 and -0.5 and between 1.0 and 0.5 were considered strong (Cohen, 1988).

Results

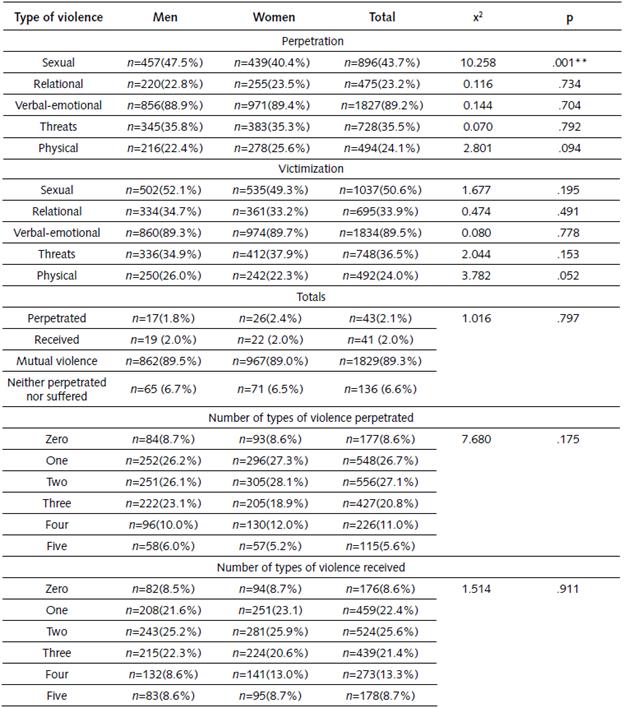

As observed in Table 2, the majority of the participants reported having perpetrated, but also suffered, at least "rarely", some of the behaviors that appear in the CADRI (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006), being low the percentage that only perpetrated or only suffered this type of conduct. The most frequently reported type of violence was verbal-emotional, both perpetrated and suffered, reaching almost 90% of the participants, followed by sexual violence (perpetrated and suffered), threats (perpetrated and suffered), relational violence (suffered), physical violence (perpetrated and suffered), and relational violence (perpetrated). Regarding sex differences in prevalence, there was only a statistically significant difference in that a higher percentage of men reported having perpetrated sexual violence. As for the number of types of violence, perpetrated and received, the highest percentages corresponded to the infliction and victimization of one and two types of violence, being lower with respect to three, four, and five types of violence. There were no statistically significant differences by sex (see Table 2).

Table 2 Prevalence of Perpetration and Victimization of Dating Violence and Number of Types of Violence Perpetrated and Received.

Note. n: total sample size; n: subsample; x 2 : Chi squared; p: probability. The number of participants who reported having perpetrated or received violence at least "rarely" is presented.

**p≤.01

By city, the prevalence followed the same pattern as at the general level, with verbal / emotional violence being the most perpetrated and received, thus: (a) Bogotá: perpetrated: 85.4 % and received: 85.9 %; (b) Bucaramanga: perpetrated: 91.5 % and received: 91.5 %; (c) Ibagué: perpetrated: 88. 7% and received: 91.8 %; (d) Tunja: perpetrated: 89.5 % and received: 90.5 %, and (e) Yopal: perpetrated: 93.3 % and received: 90.4 %. The sexual prevalence was as follows: (a) Bogotá: perpetrated: 38.8 % and received: 45.2 %; (b) Bucaramanga: perpetrated: 48.8 % and received: 53.1 %; (c) Ibagué: perpetrated: 43.3 % and received: 51.8 %; (d) Tunja: perpetrated: 43.9 % and received: 52.9 %, and (e) Yopal: perpetrated: 47.9 % and received: 53.6 %).

Threats were reported as follows: (a) Bogotá: perpetrated: 32.1 % and received: 33.9 %; (b) Bucaramanga: perpetrated: 43.8 % and received: 39.6 %; (c) Ibagué: perpetrated: 35.1 % and received: 35.1 %; (d) Tunja: perpetrated: 32.8 % and received: 36.3 %, and (e) Yopal: perpetrated: 38.3 % and received: 39.8 %. Relational violence was described as follows: (a) Bogotá: perpetrated: 20.5 % and received: 30.6 %; (b) Bucaramanga: perpetrated: 27.7 % and received: 41.2 %; (c) Ibagué: perpetrated: 22.3 % and received: 33.1 %; (d) Tunja: perpetrated: 20.3 % and received: 34.3 %, and (e) Yopal: perpetrated: 27.9 % and received: 34.6 %.

Finally, physical violence was reported as follows: (a) Bogotá: perpetrated: 20.8 % and received: 21.7 %; (b) Bucaramanga: perpetrated: 35.0 % and received: 28.5 %; (c) Ibagué: perpetrated: 20.3 % and received: 22.1 %; (d) Tunja: perpetrated: 23.6% and received: 25.1 %, and (e) Yopal: perpetrated: 26.2 % and received: 25.4%.

Regarding the frequency of aggressions perpetrated and received, trends similar to prevalence were observed, with verbal / emotional aggressions being more frequent, followed by sexual assaults, threats, physical attacks, and relational aggressions. Men reported having performed a higher frequency of sexual violence acts, while women showed more verbal / emotional and physical violence, as well as a higher frequency of violence in general (see Table 3).

Table 3 Sex Differences in the Frequencies of Violent Behaviors Perpetrated and Suffered and the Number of Types of Violence Reported

| Type of violence | Men M (SD) | Women M (SD) | t | p | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetration | |||||

| Physical | 0.49 (1.251) | 0.64 (1.460) | 2.551 | .011* | .110 |

| Verbal/emotional | 5.87 (4.717) | 6.55 (5.293) | 3.090 | .002** | .136 |

| Sexual | 1.04 (1.490) | 0.85 (1.368) | -2.996 | .003** | .133 |

| Relational | 0.42 (0.977) | 0.45 (1.026) | 0.705 | .481 | .030 |

| Threats | 0.65 (1.134) | 0.65 (1.173) | 0.152 | .879 | 0 |

| Total | 8.46 (7.082) | 9.16 (7.961) | 2.095 | .036* | .093 |

| Number | 1.98 (1.38) | 1.98 (1.22) | 0.024 | .981 | 0 |

| Victimization | |||||

| Physical | 0.68 (1.553) | 0.58 (1.469) | -1.488 | .137 | .066 |

| Verbal/emotional | 6.85 (5.384) | 6.69 (5.554) | -0.643 | .520 | .029 |

| Sexual | 1.23 (1.668) | 1.17 (1.671) | -0.719 | .472 | .036 |

| Relational | 0.80 (1.432) | 0.79 (1.491) | -0.146 | .884 | .007 |

| Threats | 0.69 (1.260) | 0.75 (1.308) | 0.935 | .350 | .047 |

| Total | 10.24 (8.664) | 9.97 (9.127) | -0.687 | .492 | .030 |

| Number | 2.21 (1.54) | 2.15 (1.30) | 0.52 | .602 | -.042 |

Note. M: Mean; SD: standard deviation; t: Students' t-test result; p: probability; Cohen's d: effect size obtained with Cohen's formula.

*p≤.05 **p≤.01

The results obtained with the unidirectional MANOVA indicate statistically significant differences by sex in the frequency of maltreatment, with a large effect size: F (6, 2042) = 5.58, p = 0.00001; Wilk's Λ = 0.984, partial η2 = 0.16. These results indicate, specifically, that sex has a statistically significant effect, although with a low effect size, on the frequency of carrying out physical violence behaviors: F (1, 2047) = 6.39; P = 0.012; partial η2 = 0.003, verbal / emotional: F (1, 2047) = 9.42; P = 0.002; partial η2 = 0.005, and sexual: F (1, 2047) = 9.07; P = 0.003; partial η2 = 0.004. There were no statistically significant differences regarding violence received: f (6, 2042) = 1.63, P = 0.134; Wilk's Λ = 0.995, partial η2 = 0.005.

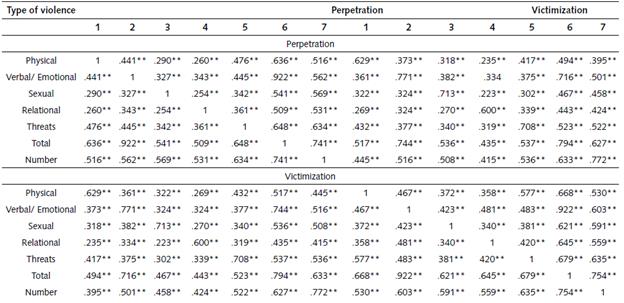

As observed in Table 4, the frequency of all types of violence was correlated with each other, both perpetrated and received. The correlations were, in general, moderate between the different types of violence perpetrated and received. However, these correlations were high between the total number of maltreatments perpetrated and the different types of violence inflicted and received and between the total number of maltreatments received and these types of violence. The correlation was also high: (a) between the total frequency of maltreatment perpetrated and received, (b) between verbal / emotional violence perpetrated and received, and (c) between verbal / emotional violence perpetrated and received and the frequency total maltreatment perpetrated and received.

Table 4 Correlations Between the Frequency of Violent Behaviors Perpetrated and Suffered (Pearson’s Formula).

Note. 1: Physical violence; 2: Verbal/emotional violence; 3: Sexual violence; 4: Relational violence; 5: Threats; 6: Total frequency of violent behaviors; 7: Number of types of violence reported.

*p≤.05 **p≤.01

Both the number of types of violence perpetrated, as well as the number of types of violence received, correlated significantly (although in a moderate way), with the different types of violence perpetrated and received, although this correlation was high with the frequency of verbal violence / emotional perpetrated. There was also a high correlation between the number of types of violence perpetrated and those received.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine the prevalence and frequency of perpetration and victimization of different types of DV among adolescents from 13 to 19 years old in five capital cities of Colombia, making comparisons by sex. Most of the participants reported having perpetrated and received one of the DV behaviors that appear in the CADRI (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006), at least "rarely".

At a general level and in samples from all cities, the most reported type of violence was verbal / emotional, followed by sexual violence, threats, physical and relational violence, with a significantly higher percentage of men reporting having used sexual violence. The frequency of the DV behaviors perpetrated and received evidenced a similar trend in terms of the types of violence, with men showing a significantly higher frequency of sexual violence acts and women displaying more verbal / emotional and physical violence, results confirmed with the one-way MANOVA that validated a statistically significant effect of sex on prevalence. However, the effect sizes of sex in each type of DV were small.

These results are consistent with those of studies that reveal high levels of bi-directionality in the DV among adolescents (Redondo et al., 2017; Karsberg et al., 2018; Ybarra et al., 2016). They are also consistent with the results obtained from the research reported by Rubio-Garay et al. (2017) and Wincentak et al. (2017), that indicate, in general, that a greater proportion of men have inflicted sexual violence, while a greater proportion of women has perpetrated physical and psychological violence. However, they are not consistent with those of research indicating that a higher percentage of women have received both psychological and sexual violence (Niolon et al., 2015; Reed et al., 2017).

At the national level, the results are consistent with those reported in previous studies carried out with another instrument (Martinez et al., 2016; Rey, 2009; Rey, 2013), in the sense that psychological violence was the most prevalent, although in these studies physical violence was more common than sexual violence. Rey (2013) also found a significantly higher proportion of men who had practiced sexual violence, while Martinez et al. (2016) and Rey (2009), also found no statistically significant differences by sex regarding victimization by emotional, physical and sexual violence.

In the research carried out by Redondo et al. (2017), with the same instrument used in this research, a significantly higher prevalence of verbal / emotional violence was found, followed by relational and physical violence (they did not examine sexual violence), although they only found a statistically significant difference by sex, in the sense that a higher proportion of women reported having received physical violence.

The results obtained also indicate that approximately a quarter of the participants had perpetrated and received two types of violence, although this percentage decreased as the number of types of violence perpetrated and received increased. There were also no statistically significant differences by sex in terms of the number of types of violence perpetrated and received, unlike Karsberg et al. (2018), who found that a significantly higher proportion of men had perpetrated two or three types of violence. These results, along with those of the correlations, tend to confirm that the different types of DV occur at the same time, as evidenced in several previous studies (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017; Wincentak et al., 2017; Karsberg et al., 2018; Ybarra et al., 2017). The fact that verbal / emotional violence had correlated so high (over 0.90), both with total violence perpetrated and with violence received, indicates that this form of violence accompanies other types of DV in adolescence.

In conclusion, the results obtained in this research indicate that DV is a very widespread problem among Colombian adolescents, so the possibility of declaring it a public health problem as in other countries should be considered (Ludin et al., 2018; Mercy & Tharp, 2015; Peterson et al., 2018; Temple et al., 2013; Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2019; Wincentak et al., 2017). Such results also point out that the type of violence most frequently perpetrated and suffered is verbal / emotional and that mutual violence is very common, reaching almost 90% of the participants in this study. Likewise, they show that sex could have a statistically significant effect on the prevalence of the different types of DV, with a significantly higher proportion of men engaging in sexual violence and a higher proportion of women engaging in verbal / emotional and physical violence.

Therefore, various investigations that allow increasing knowledge about risk factors and difficulties associated with DV in Colombia are required to develop awareness campaigns on this problem, as well as identification and early intervention of cases and primary and secondary prevention of this phenomenon among the Colombian adolescent population. These campaigns should particularly consider the prevalence of verbal / psychological violence and mutual violence.

Strengths of this research include the sample size, the participation of adolescents from five capital cities of the country, and the various statistical analyses implemented and the use of a specialized instrument on DV that has adequate reliability and validity indexes, thus avoiding the negative effects of the use of different measurement instruments (Wincentak et al., 2017). However, as limitations, it should be mentioned that these adolescents were not randomly selected and that the self-report questionnaires show biases associated with desirability and memory. On the other hand, the aforementioned instrument showed several alpha values between .70 and .80 and even one below .60 (the component of sexual violence received), which indicates that its results could have an acceptable reliability and, therefore, should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, only adolescents enrolled in school from certain regions of the country participated, so the results obtained could not be generalized to adolescents not enrolled in school and from other regions.

Taking into account these limitations, it is recommended for future research on the prevalence of DV in Colombia, the random selection of participants, the use of previously validated instruments that show high reliability indices, a methodology that minimizes social desirability and memory biases, and the inclusion of non-schooled participants and from other Colombian regions.