Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.69 Bogotá Jan.June 2009

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS

NGOs and Businesses Move from Conflict to Cooperation

DEL CONFLICTO A LA COOPERACIÓN

ONG y empresas en busca de una meta común

Carsten Wieland

Consultant, researcher, journalist, and historian. Former director of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Colombia. carsten.wieland@gmx.de.

Recibido 08/10/08, aprobado 04/04/09

RESUMEN

Los esfuerzos de las ONG para promover entre las empresas comportamientos sostenibles han logrado ganar el apoyo del público y han llegado a producir un creciente número de acuerdos internacionales voluntarios, iniciativas de políticas públicas e incluso regulación estatal. Algunas compañías han trabajado para superar la estigmatización intentando convertirse en ciudadanos corporativos responsables. Mientras que muchas otras compañías aún están tratando de evadir el debate acerca de la RSC y sus estándares de reporte, otras han ajustado sus estructuras para adoptarlos. Aunque esto tiende a aumentar los costos a corto plazo, la mayoría de las compañías que aceptan la RSC han logrado tener un mejor desempeño económico que las que se niegan a largo plazo. Las que cumplen han demostrado que son capaces de adaptarse más rápidamente a nuevos desafíos del mercado o a la reglamentación estatal. Además, los patrones de consumo parecen remunerar este comportamiento. En el espacio de una década, la cooperación entre industrias y ONG se ha convertido en un tema corriente, ha llevado a dinámicas de sinergia y ha rendido soluciones creativas.

Palabras Clave: Responsabilidad social corporativa, sostenibilidad, ONG, comportamiento de industria, sociedad civil, abogacía.

ABSTRACT

The struggle of NGOs to promote sustainable behavior from companies has successfully gained public sympathy, and has triggered a rising number of international voluntary agreements, public policy initiatives, and even state regulations. Some companies have worked their way out of stigmatization and tried to become responsible corporate citizens. While plenty of other companies are still trying to evade the CSR debate and the reporting standards therein, others have adjusted their structures to adopt them. Although this tends to raise costs on a short-term basis, most of the CSR-friendly companies have managed to economically outperform the deniers in the long run. Compliers have proven that they are able to adapt more swiftly to new market challenges, or state regulations. In addition, consumer patterns seem to reward CSR behavior. Within a decade business-NGO cooperation has become a mainstream issue, and has led to many synergetic dynamics and yielded creative solutions.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility, sustainability, nongovernmental organizations, business behavior, civil society, advocacy.

Introduction

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and businesses have long been at loggerheads with each other. This was particularly obvious in the 1980s and 90s when globalization had become an issue for many civil society activists that spurred resentment against capital and companies worldwide.1 This culminated with the massive protests during the summit of the World Trade Organization in Seattle 1999.

After capital flow had become borderless and transnational, leftist and social-democratic governments in industrial states have had a hard time to hold on to conventional domestic policy tools in finance and economics to defend policies of social balance. Governments in developing countries had even fewer means to counter the rising influence of transnational and/ or multinational cooperation that often possessed more assets and capital than the government budgets of the poorer states.

This paper outlines how NGOs have faced the challenge of the initial advantage of business interests during the development of globalization with a new strategy of engagement. The change of approach from confrontation to cooperation entails successes, opportunities, and dangers that are mentioned in the following chapters. The overall impact of NGOs in this field is hard to quantify, although there are lot of good case examples and spillover effects into national and international institutions as well as into public policy. Despite the lack of quantitative data one can certainly conclude that within less than a decade business-NGO cooperation has become a mainstream issue and triggered many synergetic effects and creative solutions.

1. Tackling the Asymmetry of Globalization

Especially after the end of the Cold War, NGOs have been forming more powerful international networks and managed, in many ways, to establish a counterweight to market forces, influencing transational behavior and activities. Additionally, in the 1990s the United Nations, which had traditionally focused on state actors, started to increasingly engage NGOs on a political level and thus contributed to their growing visibility and influence.

Meanwhile, on the organizational level, it has sometimes become difficult to distinguish between NGOs and business associations or a combination of both with an international organization like the United Nations and its numerous sub-organizations. We are facing a landscape of overlaps, of transversal interests and relationships.

Another particularity is that it has often become impossible to distinguish between national and interational NGOs because their shared concerns transcend borders, and the companies that these NGOs are in contact with are mostly multinational as well. Ye t another characteristic is that NGOs have organized themselves not only around companies but also like companies in order to compete with their organizational structures and power. This includes overarching organizations ("conglomerates") and networks of likeinded national and international NGOs. Different levels of organizational structure have made the scene even more complex.

This success in combining synergies has led some scholars to bring forward a normative, although contentious, notion of a global civil society: a kind of global public opinion, a global deliberative society beyond conventional institutions of participation (Anheier, Glasius and Kaldor 2005). Along the same lines, the German political scientist ErnstOtto Czempiel proposed the term of the "world of societies" (Gesells-chaftswelt) as opposed to the world of states (Staatenwelt) and ideological block confrontation (Czempiel 2002: 15) . However, this hopeful scenario has given way to more skeptical assessments, particularly after the rise of ethnoolitical conflicts in the 1990s and a reocusing on national power in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks and the "war on terrorism".

This is the background against which international civil society forces are at work today. Simultaneously, after a phase of confrontation between NGOs and business actors, the turn of the millennium has brought the breakthrough of a new, more inclusive and conciliatory approach.

2. A New Strategy

Far reaching cooperation between NGOs and companies is a recent phenomenon of the past five to eight years. The more surprising fact is the rapid spread of this strategy. Not only has the number of engaged and specialized NGOs in this field mushroomed internationally. Their efforts have also led to definite changes in corporate behavior and public policy.

The agenda is less generally seen as "changing the world" or "fighting globalization" than a focus on concrete issues and projects, on piecemeal progress, while using the same tools of globalization for the purpose of sustainable development. Sometimes this has been going hand in hand with compromises and unprecedented partnerships between NGO's and businesses. New terms like corporate social responsibility (CSR) or even corporate citizenship entered the debate. As these terms indicate, the line between the dichotomous concept of civil society on the one hand and of market driven behavior and interests on the other is being blurred. Innumerable NGOs have specialized in promoting CSR, stakeholder participation in conflict, and sustainable investment have been expanding worldwide. This has also become a new market for forproft consulting firms and think tanks. On the other side of the table, businesses themselves have taken the initiative and formed voluntary associations for the same purposes.

One of the early pioneers of this new approach started its work as early as 1985. RAN (www.ran.org) began a corporate responsibility campaign aimed at "convincing key corporations to respect endangered forest ecosystems and the rights of indigenous peoples" (RAN website) . It mobilized its 30,000 members and 150 Grassroots Rainforest Action Groups, building alliances with environmental activists and attracting media attention.

Other precursors of a comprehensive approach, that aimed to influencing international public opinion and public policies in a constructive way, were the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that entered into force in March 1994, the World Summit for Social Development in Copenhagen in 1995, and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) founded in 1997.

Nevertheless, during the 80s and 90s such international initiatives developed hand in hand with a more militant mainstream involving protests and verbal attacks against private companies and "globalization", as such. The symbolic turning point was the deadlock and the sweeping demonstrations in 1999 at the WTO summit in Seattle. At that time it became clear to both sides that confrontation only would not lead to solutions. From this moment on, activists, often those who once protested in the streets have been sitting at round tables with business leaders, government representatives, and negotiators from international organizations.

During this watershed year, for example, one of the most active and visible NGOs in this area, International Alert (IA) in London, started its focus on businesses and dialogue with them. However, dialogue alone would not suffice. Important preparatory work has been done by protests, advocacy, and activists who track the records of companies. Jessie Banfield from IA openly concedes: "Our work would not be possible without research of NGOs who take a more confrontational approach."2 The synergetic efforts comprise public campaigns, media engagement, raising awareness, and consumer boycotts as much as dialogue and cooperation. Some NGOs, such as Amnesty International, pursue a dual approach of campaigns in public and dialogue behind the scenes.

Banfield points out that dialogue becomes more important when companies face conflict situations; otherwise, polarization and deadlock are likely outcomes. IA's advocacy has become more focused, and it includes practical recommendations for companies on how to develop their CSR strategies. Nevertheless, Banfield would not go as far as to describe her work as a "service" for companies. It is the motivation of NGOs that make the difference, she says, which goes beyond a mere service. It comprises the vision for a better world and the necessity of dialogue.

A large number of NGOs are working on issues relevant to corporations and conflict resolution in what respects to their business activities. They do research into the impact of companies in conflictprone zones. These NGOs represent a wide range of perspectives, from local to international; and target audiences from consumers to industry representatives and national governments, and employ an equally wide range of methods. The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) and the Ijaw Council for Human Rights, for instance, both engage companies at the community level (Banfeld, Haufer and Lilly 2003: 63-64).

A new string of thought and action in the NGO-business relationship is regarding the importance of peacebuilding. This is an explicit goal mentioned by the UN Global Compact. It has growing potential as also Banfeld, Haufer and Lilly (2003: 58) point out: "Partnerships involving business, civil society and governments (and/or international organizations) are in vogue. This trend provides a significant opportunity for TNCs [transnational corporations] to fulfill their potential to contribute to peace building, but much more research needs to be done in order fully to understand its implications for TNCs and conflict."

In this context, three NGOs, The Council on Economic Priorities, International Alert, and The Prince of Wales Business Leaders Forum, published a widely acknowledged report in 2000: The Business of Peace (Nelson 2000) . It provides a framework for understanding the positive and negative roles that business can play in violent conflicts. The report states that "both domestic and multinational companies have an increasingly important role to play in conflict prevention and resolution" and that "in today's global economy they also have a growing business rationale for playing this role" (Bennett 2001). Fort and Schipani (2004, 2) argue along the same lines and emphasize three possible contributions of businesses toward peace: Reduction of bloodshed brought about by ethical business practices, including peace as a "governance telos" in corporate governance, and an increasingly important role of businesses and their peaceful practices in foreign policy.

This strategy is not without its own dangers and failures. As Banfield pointed out in our interview, some companies try to bring NGOs to a dialogue and enjoy the resulting favorable media coverage, without changing much in practice. This is why the dual strategy is necessary of tracking records and launching campaigns on the one hand and engaging in constructing dialogue on the other hand.

3. Beyond Philanthropy

It is important to distinguish CSR from philanthropy. Philanthropy basically means giving back to society the wealth that a successful entrepreneur has accumulated. The way how it was accumulated is not subject of scrutiny. Kakabadse, Rozuel and LeeDavis (2005: 283) point out that "by itself, philanthropy (or charity) does not necessarily mean that a firm develops a broader strategy to comprehensively assess its impacts on society, and to design plans, policies and tools to improve its overall performance towards society." By contrast, CSR is a long term perspective of economic gain that incorporates a vision of a good environment and society, and that takes this vision into account from the first steps of a planning process. Carroll (1991:42) defines CSR as a pyramid made up of four layers that consist of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities. CSR clearly goes beyond philanthropy, and Carroll argues that the first three responsibilities are even more important than philanthropy itself.

Although CSR still lacks internationally accepted criteria for definition, or a common paradigm (Kakabadse, Rozuel and Lee-Davies 2005) , the practical effects of behavioral change have already been remarkable. For many companies it has become part of their business philosophy to integrate social and environmental concerns, or at least to worry about not being on the list of "good guys". Some even compete in gaining the strongest image as a good "corporate citizen."

4. Unusual Business and the Notion of Civil Society

All in all, we have entered the second phase in the trial of strength between civil society and market forces. In this scenario of increased cooperation, both sides have come a long way, and sometimes even slaughtered sacred cows. Former UN Secretary General Kof Annan expressed the need to rethink in a heartfelt appeal: "We will have time to reach the Millennium Development Goals worldwide and in most, or even all, individual countriesbut only if we break with business as usual."3 At the Business-Humanitarian Forum in Geneva on January 27, 1999, Annan summarized a message delivered at various economic summits and business gatherings: "A fundamental shift has occurred in the UN-business relationship," he noted. "The United Nations has developed a profound appreciation for the role of the private sector, its expertise, its motivated spirit, its unparalleled ability to create jobs and wealth. [... ] In a world of common challenges and common vulnerabilities, the United Nations and business are finding common ground."4

How do these developments ft into the conventional notion of civil society? Discussions about how to define civil society mainly oscillate between a normative notion of "civil"a type of societyand a more descriptive or analytical approach towards civil society actors as a part of society without making normative assumptions or setting preconditions about the behavior of individual members, or of society as such (Edwards 2004: vii) . Moreover, a distinction is made between the poles of private economic interests at one extreme, and associational life at the other, and to what extent civil society is seen as linked to the state, or as separate from it (Hyden 1998) .

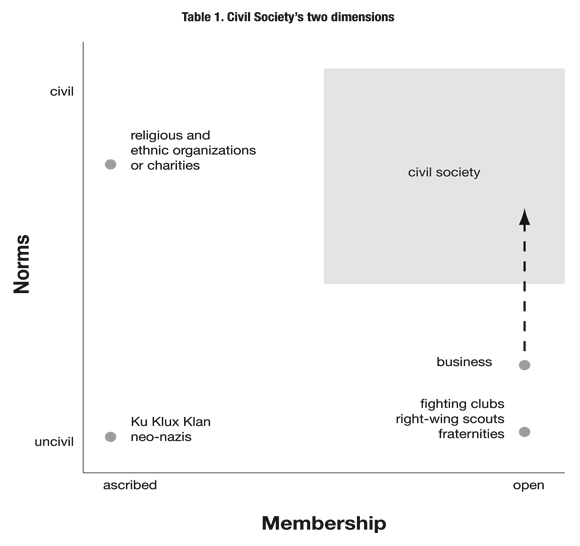

Those who focus merely on the unhindered play of the free entry to, and the free exit from associations as a definition of civil society, like the neoTocquevillians, neoliberals or even neo-Lockians, face criticism for a simplistic view of pluralism, and for neglecting the "uncivil" as well as the highly self-interested nature of some organizations and associations. Even though this criticism is valid, I do not see an unavoidable incompatibility between, say, Tocqueville's approach, and the normative approach Edwards (2004) or Anheier, Glasius and Kaldor (2005) suggest. I understand civil society along both axes, i.e. as being subject to preconditions related to norms and membership. The following chart depicts this idea and also relates it to the question of how and where business fits in considering the new developments just described.

According to this chart, the definition of civil society is narrowed down to fulfill the preconditions of both sufficiently open access, and a certain degree of adherence to norms of "civility". Tocqueville's idea of free access is equally important as the concern, that under the cover of free membership, not everything is permissible. This is why we have an empty fringe on the horizontal and on the vertical planes where civil society, according to this definition, does not exist.

Religious and ethnic organizations, for example, can be very exclusive and detrimental to the coherence of a society and the common good. Membership in such organizations follows ascription instead of free choice, and sometimes leaving them is not allowed, depending on the degree of parochialism of certain primordial communities, which represent rather a Gemeinschaft than a Gesellschaft in terms of Tönnies. Primordialist groups intend to transform parts of society (in the Tocquevillians sense) into communities. A purely "ideal, mechanical" link of otherwise separated people is substituted by the bond of "real and organic life", an apriorical "unity of will". Tönnies continues to describe the contrast between society and community as follows: "Society is the public, it is the world. In the community of one's own, one is bound right from birth, with all the weal and woe. One goes into society as into alien lands." And: In society no activities take place, "which can be traced from a unity that exists a priori and necessarily" (Tönnies 1972 [1887]: 3) .5

Nevertheless, primordial organizations, especially religious ones, can be highly ethical in regards to the norms ("civility") . On the other axis of the chart they can open up and become more inclusive in their outlook and membership policy. In this way these communities can contribute to a vibrant civil society. This is why they partly overlap in this definition of civil society, depending on what kind of organization we are talking about.

To what extent business is, or can be, a part of civil society has remained an open question. Mostly, it is excluded from the definition because it follows the pattern of market logic and self-interest. As Edwards (2004: 27-28) sums up, one strong stream of thought considers civil society a "market-free zone" (Michael Walzer, Christopher Lasch) , while others see business as an integral part of civil society (Ernest Gellner) .

I argue that we are witnessing a dynamic process. Manchester capitalism is definitely not part of civil society, but the philosophy of many business leaders has changed in a process that has become more and more institutionalized since the turn of the millennium with the help of local, national, and international agreements. The interesting aspect is that only a minority of entrepreneurs might have a genuine interest in social justice and sustainable development. The majority of corporate decision-makers have been, rather, pushed by NGOs and their campaigns, often targeting consumer behavior, into a more sustainable direction. It was the confrontational approach of phase I in NGO-business-relations that have changed the course, and it seems that the vision of cooperation still needs the threat of potential confrontation to support its cause. Today, if business leaders follow a cooperative approach, they do so because of self-interest. It simply pays to do so. Their reputation is at stake if they do not follow the new rules set by the organized protagonists of civil society.

Already in 1999 Rosabeth M. Kanter wrote that, although "traditionally, business viewed the social sector as a dumping ground for spare cash, obsolete equipment, and tired executives," today the private sector tends "to approach the social sector [... ] not as an object of charity" but as an opportunity for "a partnership between private enterprise and public interest that produces profitable and sustainable change for both sides."

So the dynamics I see is that businesses, with their various cooperation initiatives, as well as its social and environmental activitiesencouraged and often accompanied by NGOsis pushing its way into the realm of civil society, at least partly, as represented in the chart. There is, of course, still a long way to go. Nevertheless, a change of paradigm has taken place in NGO -business-relationships. This could trigger synergetic effects and free resources of all stakeholders for the benefit of the civil societies and the environment. Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan summed up the new field of action in this millennium as follows: "The United Nations once dealt with Governments. By now we know that peace and prosperity cannot be achieved without partnerships involving Governments, international organizations, the business community and civil society. In today's world, we depend on each other."6

5. The Great Bear Rainforest Example

The following example tells the story of a successful NGO-business cooperation while hinting at challenges and shortcomings as well.

An agreement was reached in early February 2006 in Canada to preserve the Great Bear Rainforest, the largest remaining temperate coastal rainforest on Earth. The stakeholders of the difficult compromise are officials from the provincial government, coastal native Canadian nations, logging companies, and environmental groups. The agreement creates a lasting model of conservation by formally protecting five million acres of from logging, and establishing a process to develop ecosystem-based management across an additional ten million acres. Negotiations are on-going for similar land use agreements across an additional six million acres. A central component of the project is an innovative $120 million conservation financing package to fund conservation management projects and ecologically sustainable business ventures in First Nations territories.

This is a result of a decade-long fight that comprised all the possible features of a confrontation between business and civil society activists. Greenpeace, ForestEthics, Rainforest Action Network and the Sierra Club of Canada came together to target destructive logging in the Great Bear Rainforest. The groups' efforts culminated in critical pressure from forest product customers. Over 80 companies, including Ikea, Home Depot, Staples and IBM, committed to stop selling wood and paper products made from ancient forests. Marketplace pressure drove logging companies to sit down and negotiate with environmentalists. The NGOs also launched sit-ins in the forests by Native Canadians and environmentalists who chained themselves to logging equipment.

But the risk remained that at any given point of time one of the stakeholders would attempt to opt out of the process, including the government of British Columbia, which seemed to fail to keep its promises in 2005. It took many years of nervewracking protests and negotiations until this new design of tripartite business-government-NGO cooperation was finally reached.

"It's like a revolution," the New York Times quotes Merran Smith, director of the British Columbia Coastal Program of Forest Ethics, an environmental group. "It's a new way of thinking about how you do forestry. It's about approaching business with a conservation motive up front, instead of an industrial approach to the forest." Under the agreement, the loggers will be guaranteed a right to work in ten million acres of the forest, which some environmentalists still criticize. But they will be obliged to cut selectively: away from critical watersheds, bear dens and fish spawning grounds, negotiators said. Among the supporters of the agreement are some of the biggest players in Canadian lumber and paper industries, including Western Forest Products, Interfor and Canfor. "It's a cultural shift," said Shawn Kenmuir, an area manager for Triumph Timber, which has already forsaken old clear-cut practices. "We've started the transition from entitlement to collaboration" (Krauss 2006) .

This success story does not detract from the problems that are involved in such compromises. This example is also a tale of NGOs turning into businesses themselves, while facing the danger of losing credibility. The Washington Post ran a series of stories that tackled Nature Conservancy that is a party to the Great Bear deal. It is the world's richest environmental group, amassing $3 billion in assets. Critics argued that Nature Conservancy aligned too closely with corporations. In addition to land conservation, it pursued drilling, logging and development. One article criticized: "A look inside the Nature Conservancy reveals a whirring marketing machine that has poured millions into building and protecting the organization's image, laboring to transform the charity into a household name."7 There are several instances where, according to the reports, the NGO pursued cooperation initiatives with businesses that turned out to be questionable from the environmental point of view or were a waste of money. Thus, as the Washington Post concluded, "the results illustrate how the organization's philosophy and profit pursuits can put its core mission at risk." NGO representatives denied the charges and said that their accounting records were open books.

This example shows that with the new approach of compromise NGOs pursue a dangerous path. They can become too dependent on their clients, or fall victim to the pressure for success that, in turn, is a precondition for raising more money. As with the Nature Conservancy, a diversified income base, as in developed countries, is no guarantee against such failures. One can only imagine how severe the pressure is for NGOs from developing countries, as also Edward (2004:102ff) illustrates. Appropriation by governments is as risky as appropriation by businesses. The tugo-war between civil society and businesses is still going on through different means, while the call for stricter accounting and transparency of NGOs is getting louder.

6. Tracking the Global Impact

Measuring the overall impact and success of NGO pressure and partnerships is very difficult. Often examples of good experiences overshadow the greater picture. Nevertheless, there are several indicators that facilitate evaluating this development.

One of those instruments is polling. Research indicates that, meanwhile, a majority of business leaders takes this issue very seriously and considers CSR as a factor of business performance, as something that pays off (Mercer Investment Consulting 2006) . Consumers, for their part, have shown a growing awareness and are ready to boycott or blacklist identified wrong-doers (Vassilikopoulou and Siomkos 2005) .

Some other and well-known examples of NGO-business cooperation are: Greenpeace International persuaded refrigerator maker Whirlpool Corp. to use environmentally friendly insulation. Gap Inc. and Nike Inc. have collaborated with labor advocates to clean up sweatshops in Cambodia. Prodded by consumer activists, Dell Inc. and Hewlett-Packard Co. are working with consumer groups to step up recycling of computers and cut down on toxic waste. Activists are, also, collaborating with Procter & Gamble Co. and Coca-Cola Co., to name two, to hasten the acceptance of codes of conduct and other measures designed to boost socially responsible corporate behavior (Iritani 2005) .

Particularly, northern-based NGOs, due to their influence through the media over consumer and shareholder perceptions, as well as their proximity and access to multinational corporations, have played a major role in the emergence of a CSR agenda (Banfeld, Haufer and Lilly 2003: 16) . This is why northern-hemisphere companies are much more exposed to scrutiny than businesses from developing countries.

This means, in turn, that the latter can still act in a sheltered environment. In some cases companies of developing countries take over problematic businesses where northernhemisphere corporations have pulled out because of CSR-related conditions posed by the World Bank or pressure from NGOs. One example are Chinese companies in Africa that are more concerned with shortterm profit and influence, instead of human rights and other CSR concerns.8

A consideration of the mining industry comes to a similar conclusion. Out of the ten biggest gold mining companies, only one has not published any report on their environmental and social policy: it is the only company that has its headquarters in Ghana instead of in a developed country with a CSR tradition (in this case including South Africa, Yakovleva 2005: 72, 81) . Therefore, a new generation of activism for company involvement may likely focus on those actors as well. But, despite recent success, NGO resources are limited and mobilizing public opinion in non-democracies like China is extremely difficult. So we are facing a certain asymmetry here. The success of NGO-business cooperation has largely been a northern/western phenomenon, spurred by public opinion under democratic conditions.

The discourse in this field has, so far, lived on good practice studies and qualitative research. As mentioned above, it is very difficult to measure the effect of NGO-business cooperation efforts in a quantitative way. Due to the vastness of different organizations in a growing number of countries, no reliable data is available concerning the numbers of NGOs that are involved in this area worldwide. An indepth countrytocountry study would be necessary, also because several initiatives remain focused on national, regional, or even community level. A growing number of NGOs in this field, however, have formed associations at the global level.

In order to get an idea of the scope of the efforts in this area, we can at least look at some efforts done to quantify the scene, for example, by Business Ethics Magazine that has identified more than 200 groups and publications worldwide in the areas of consumer issues, corporate governance, economics and public policy, environment, ethics and social responsibility, human rights and labor.9

Another approach to a hold on measurements is an indepth business sector study as Yakovleva (2005) has done with the mining industry. But even here, most of the evidence is of a qualitative nature. One quantitative indicator, however, is to measure the expenditure of corporate foundations in crisis regions respectively at the location of production or investment. Yakovleva (2005: 225) has collected data from her field. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to directly relate these figures to the intensity of NGO activity or to the density of NGOs in a respective country where the company operates.

7. Public Policy Spillovers and Voluntary Regulations

Another approach entails looking at the spillover effects into institutions or legislation. A few milestone examples of spillovers into public policy are:

-

The 1995 UN World Summit on Social Development has triggered several initiatives towards this, like the Copenhagen Centre (TCC) , established by the Danish Government to further international progress in CSR and promote new partnerships for social and labor market integration.

-

The Kyoto Protocol (Framework Convention on Climate Change) of 1997 has an impact on energy prices and controls on the release of greenhouse gases. This has triggered new efforts and partnerships in areas of shared interest.

-

In 1997 the World Bank created the Post-Conflict Unit as part of its social development department. The unit advises the bank on how its lending policies can help to prevent conflict and promote social cohesion, while at the same time promoting economic growth and poverty reduction. Since then, involvement of NGOs in World Bank policies has steadily increased.

-

The UNGC aims have been mirrored in the UN Millennium Development Goals.

-

On 20 December 2000 the governments of the United States and Great Britain finalized the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, an important agreement by several major oil and mining companies to voluntarily support a set of human rights principles governing their use of security forces in foreign operations.

-

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) was launched by British Prime Minister Tony Blair at the September 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. The initiative seeks to bring governments, companies, financial institutions, and NGOs together. It is inspired by the earlier NGO campaign "Publish What You Pay".

-

The European Unión has increasingly promoted the CSR concept in declarations and legislation. The Lisbon Strategy of 2000 has defined it as a priority for the EU economic zone, which led to the Green Paper on CSR in 2001. This was further developed on in the Góteborg Summit in 2001 where the EU leaders prepared the legal ground to include social and environmental criteria in European and national procurement policies.

-

At least one of the main Seattle protester of the 1999 demonstrations was among the 70 outsiders who had the chance, in January 2005, to grill three WTO director general candidates. It was the first time in the organization's ten-year history that activists were allowed to have input in the selection process (Iritani 2005). This is a remarkable success for civil society, as well as a change of paradigm.

The most significant development in this área has been the United Nations Global Compact (announced 1999, enacted 2000) , initiated by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to concentrate the influence of multinational corporations in promoting human rights and avoiding conflict. The Compact calls on companies to embrace nine universal principles in the areas of human rights, labor standards and the environment. It brings companies together with UN organizations, international labor organizations, NGOs and other parties to foster partnerships. It aims, in the words of Kofi Annan, to contribute to the emergence of "shared values and principles, which give a human face to the global market" (UN Global Compact Brochure).

Aside from these political spillover initiatives, there have been increasing numbers of voluntary regulations established by industries without government involvement, and mostly without enforcement mechanisms. To name a few: Caux Principles (1986), Global Reporting Initiative (1997) , SA 8000 (1997), Global Principles (Benchmarks) (1998) , Global Sullivan Principles (1999) . The UN Global Compact (1999/2000) can also be listed here again since it is, despite being a hybrid, a platform of voluntary principles. The implementation of the Global Compact has taken different shapes on the different national contexts, partly with round tables including the participation of various interests, active NGO engagement, and/ or the founding of new organizations as platforms and watchdogs. Although the principles are not binding, the GC initiative has the potential of developing a gradual trickle-down effect that could lead to into national enforcement mechanisms. Much will depend on the role of NGOs, their ability to pressure national governments for legislation, and at maintaining consumer awareness.

Some codes of conduct have become examples due to their binding nature and self-enforcement. These accords have mostly risen out of conflicts in which NGOs have played an important part in raising awareness. One example is the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) . NGOs have campaigned from 1998 onwards to stop the commercialization of "blood diamonds" by pointing to the link between armed conflict in Africa and the diamond market. After three years of intense negotiations in South Africa, States, industry representatives, and NGOs reached a consensus for a worldwide certification scheme that bans trade with diamonds from conflict areas. This example is interesting, because it entails yet another actor on the international stage. The UN General Assembly is given an annual report and passes resolutions on this scheme. Countries that are not part of the KPCS have not been able to trade their diamonds since then.

8. Successes and Challenges

In quantitative terms, i.e. considering the number of participating organizations or individuals, the biggest success story is the UNGC, the world's largest voluntary corporate citizenship initiative. It has enrolled over 1500 companies and two dozen NGOs and labor groups from over 70 countries. Nearly 50 networks have been launched that reach out to the business communities and focus on engagement mechanisms, such as communications on progress, global and regional multistakeholder dialogues, learning forums and partnership projects.

The Global Reporting Initiative is the second biggest institution in this field. GRI started in 1997 and became independent in 2002. It is an official collaborating centre of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and works in cooperation with the Global Compact. Meanwhile, 817 organizations, mostly companies, have subscribed to the GRI principles. The Sustainability Reporting Guidelines are for voluntary use by organizations that compile reports on the economic, environmental, and social implications of their activities. The GRI incorporates the participation of representatives from business, accounting, investment, environmental, human rights, research, and labor organizations from around the world.

Another method to reach quantitative conclusions is to look at single events, achievements or movements. One good example is the Publish What You Pay campaign, led by George Soros. It represents a coalition of more than 130 NGOs and has raised the importance of transparency of resource-related payments. It aims to help citizens hold their governments accountable for revenue management, encouraging the governments of wealthy countries to require extractive transnational companies to publish net taxes, fees, royalties, and other payments made.

A more recent example is the Clinton Global Initiative launched in 2005. Out of the $ 2 billion in commitments that the initiative has gathered, 19 projects deal directly with business NGO partnerships. This is more than half of all projects.

Nevertheless, with regard to the Global Compact and other initiatives, one major setback has been the lack of participation of US firms. According to McKinsey and Company (2004:312) , only eight percent of all firms participating in the Global Compact are from North America, of that percentage slightly more than half (or 4.5 percent) are from the USA (based on 2004 data of The Economist) . Moreover, a comparative evaluation of the hundred fastest growing US companies has shown that their level of environmental disclosure and commitment is rather low. Only 35 out of the 100 surveyed firms provided any type of environmental disclosure. More surprisingly even, those companies with a lower level of financial performance and profit margin were more likely to have a formal environmental policy or a description of their environmental commitment than the higher financial performers (Stanwick and Stanwick 2005: 157) . This suggests the possibility of leeching on the performance of others.

Public consciousness can become lulled by some success stories, but this does not mean that there has been significant progress across the board. The fastest growing firms are likely to be the biggest polluters. NGOs should not turn away their criticizing eyes from such behavior that is not only condemnable from an environmental point of view, but also they should not do so with regard to solidarity within the corporate community. This example is representative for the difficulties to quantify success in this field.

Conclusion

Profit and sustainability are not mutually exclusive. This is one of the major messages that are the result from the new strategy of business-NGO cooperation initiatives. One may add: Profit and sustainability are not necessarily mutually exclusive. It all depends on creative solutions, on the leverage of power of each side, on the mutual deconstruction of stereotypes, and not least on the level of trust that can be built among the partners, which can ensure a longterm participation of stakeholders and the safeguarding of scored compromises.

The most fundamental measure of success is that economic and social sustainability has entered the business concepts of many companies. This has led to a dynamic where others have to follow suit if they want to keep up their performance or their market share. Sustainability has become a part of modern economic thinking, and entrepreneurs do not even have to abandon their familiar currency: profit.

Several preconditions have to be met so that these advances can be secured and broadened. One of them is education. Ecological and social awareness starts at school, and it becomes even more important in the training of young managers and executives. In the wake of the UN Global Compact, several European countries like Sweden and Austria have included management training on their concepts of promoting CSR. Rising awareness within the corporate community is a major contribution and an argument that justifies the blurring of the lines between civil society and the marketplace.

Nevertheless, as we have heard from leading NGO activists, for a foreeeable time, enhancing cooperation will not be viable without (the threat of) confrontation altogether. It will remain a tugowa between different interests. Consumer pressure is the most important component in this process, along with consumer awareness. The most nuanced aspect of this process lies in making what will and will not be tolerated clear to the offenders, also in the interest of corporate solidarity. Outcomes will be most promising and sustainable if common ground could be found between diverging interests. As we have seen in many examples, this is both possible and often conducive ecologically as well as economically. A lot has to do with the willingness to abandon old convenient models and to invest in innovative solutions that may seem risky at the beginning, but can turn out quite profitable in the long run.

While embarking on creating solutions, however, NGOs will remain exposed to the dangers of distortions, failures, along with the seduction to toady for business or government interests. The danger of cooptation is a serious challenge. Stricter NGO accountability measures are therefore necessary, as Edwards points out (2004: 102) . Not only power but also the proximity to power and money can corrupt. This is equally true about the opportunity to compete successfully in an increasingly competitive market for ideas and funding. A diversified income base reduces the volatility of NGOs to succumb to such pressure. NGOs in poorer countries face a steeper challenge in this regards, as well.

Nevertheless, the core idea of cooperation and the use of a synergetic dynamic of resources and ideas is the right way to go. The more common this concept becomes, the more institutions will adopt it, the more internalized such practices will become in business and politics, and collaboration between these unlikely allies won't seem so strange.

Annex 1. Major International Non-Governmental Organizations with CSR Agendas

In the table that I have compiled from many different internet sources, I did not include think tanks, research and news services that focus on socialeconomic partnerships. Otherwise, the list would have been much longer still. I tried to limit it to NGOs that engage in both research and action, which can range from protest, advocacy, to consulting, offering services and forming partnerships.

AccountAbility: This organization is a non-profit institute that brings together members and partners from businesses, civil society and the public sector from across the world. It is dedicated to promoting accountability for sustainable development.

Business-Humanitarian Forum: This non-profit organization seeks to assist businesses with responsible investment in conflict societies, as well as promoting cooperation between humanitarian agencies and corporations.

Business in the Community: BiTC is an organization of several hundred UK corporations (many are trans-national) whose mission is to advise its members on best practices towards corporate social responsibility.

Business for Social Responsibility: BSR equips its member companies with the expertise to design and implement successful, socially responsible business policies, practices and processes. BSR also convenes and facilitates transversal dialogue and collaboration.

Centre for Conflict Resolution: This organization, affiliated with the University of Cape Town, works for 'just and lasting peaceful resolution' to conflicts in South Africa, as well as other African nations.

Clinton Global Initiative: The CGI is a part of the William J. Clinton Foundation that strives to "increase the benefits and reduce the burdens of global interdependence." It brings together leaders from a wide variety of backgrounds, including current and former heads of state, business executives, scholars, and representatives of key non-governmental organizations.

Corporate Knights: The vision of Corporate Knights is to create a global organization that is trusted as the Canadian as well as the global source for information about the behavior of the corporate world. The organization is a driving force of the Global 100 List of most sustainable companies worldwide.

CSR Europe: CSR Europe is a non-profit organisation that promotes corporate social responsibility. Its mission is to help companies achieve profitability, sustainable growth and human progress by placing corporate social responsibility in the mainstream of business practice.

Fund for Peace: FfP is an organization dedicated to the prevention and alleviation of conditions that cause war. Its Human Rights and Business Roundtable is a forum that allows multinational corporations and human rights organizations a venue for dialogue.

Global Reporting Initiative: GRI is a multi-stakeholder process and independent institution whose mission is to develop and disseminate globally applicable Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. GRI includes representatives from business, accounting, investment, environmental, human rights, research and labour organizations from around the world. GRI is an official collaboration centre of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) .

Global Witness: This non-profit organization strives to expose environ-mental exploitation and human rights abuses, particularly where unregulated extraction of natural resources such as timber, diamonds and oil have a negative impact on local communities, especially when used to fund the conflict itself.

Human Rights Watch-Corporate Watch: The organization provides information, including commentaries, press releases, publications, and reports on the issue of transnational corporations and human rights.

Institute for Multi-Trak Diplomacy: IMTD is an organization that strives to promote a systems approach to peace building and to facilitate the transformation of social conflict, with one of the main approaches involving businesses and peace building.

International Alert: IA is a leading non-profit organization that is directly involved in conflict resolution and humanitarian relief efforts. One of IA's Policy Unitsthe Business Policy Unitdeals specifically with the role of businesses in conflict societies.

International Business Leaders Forum: The Prince of Wales' IBLF is a non-profit organization that strives to promote responsible business practices, especially in assisting new and emerging market economies, to achieve social, economic and environmentally sustainable development.

International Committee of the Red Cross: The ICRC has begun research focusing on the role of businesses in conflict areas, and the relationship of transnational corporations and humanitarian organizations.

International Institute for Sustainable Development: The IISD is an organization that counsels governments, academics and NGOs on sustainable development strategies.

International Peace Forum: IPF is a consulting group that focuses on conflict prevention and resolution.

Philias: This organization is a non-profit foundation that encourages and supports companies in developing and promoting awareness of their social responsibility.

The Stakeholder Alliance: This organization is a grassroots effort that seeks to "change the corporate system o make it responsible to all stake-holdes, instead of only to stockholders, and thus return corporations to their original public purpose." The objective is to make corporations publicly accountable through comprehensive public disclosure.

Transparency International: TI is the leading international non-governmental organization devoted to combating corruption. Its approach to achieving these goals is to bring civil society, business, and governments together in a global coalition.

Annex 2. The 2009 List of most sustainable companies in the world

The list is compiled by the NGOs Corporate Knights and Innovest Strategic Value Advisors Inc. out of data from 1800 companies. Launched in 2005, this ranking is presented on a yearly basis at the World Economic Forum in Davos. The top 100 companies represent roughly the top 5 percent performers in each of the industry groups making up the MSCI World Index.

The sources used to establish the list are annual environmental and social reports, company press releases, industry-specifc news sources, media searches, government and regulatory bodies, and the research of NGOs. Beyond this, personal interviews with company executives are conducted.

The criteria are measured as follows: The best performing companies have minimal, well-identified environ-mental nd/or social risks and liabilities. They are well-positiond to handle any foreseeable tightening of regulatory requirements, and strategically positioned to capitalize on environmentally and/or socially-driven profit opportunities.

In the listing that was presented at the Economic Forum in Davos (Switzerland) in January 2009 the US overtook the United Kingdom for the first time, considering the absolute number of the most CSR active and sustainable companies worldwide. Thus the US counts 20, the UK 19, Japan 15, France 8, Germany 7, Canada, Finland and Sweden 5, Australia, Denmark, Spain and Switzerland 3, Italy 2, and the Netherlands and Norway 1.10

In order to put these findings into perspective, I contextualized them with the gross national income per capita (World Bank Development Indicators 2009 with 2007 data). Instead of merely using GNI data, this approach is more precise about the economic potential of a country and its citizens. The method assumes that a country with greater economic power per capita also has companies that possess sufficient economic leverage to think ahead and embark on more progressive and sustainable business strategies.

Incidentally, the list would look similar if one ranked the countries according to the number of companies that participate in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).11 The flip-side, however, is that this index grasps the best performers but tells us little about the overall performance of a country's companies. This is why the US ranks relatively high. Some of the top performers are in the US, probably because they have been proportionally more exposed to international NGO pressure (like Coca Cola or Nike) and reacted accordingly. Less visible firms can hide more easily.

In their 2009 press release the NGOs Corporate Knights and Innovest Strategic Value Advisors Inc. conclude: "From its inception in February 2005, the Global 100 Most Sustainable Corporations has outperformed its benchmark (the MSCI World Index) by 480 basis points per annum to end of year 2008." Matthew Kiernan, CEO of Innovest, noted: "The continuing out-performance of the Global 100, even in the midst of the current global financial crisis, provides eloquent testimony–and yet more evidence–for investors, company executives, governments, and civil society alike: superior positioning and performance on environmental, social, and governance issues does provide a valuable leading indicator of better-managed, more agile, 'future-proof' companies. And we expect this 'sustainability premium' to become even larger in the coming years." 12

Footnotes

1 One of many examples that convey the spirits of this current are articles of Ignacio Ramonet (1999, 2000). They also deal with protests against the WTO summits.

2 Interview with the author on February 17, 2006

3 http://www.un.org/issues/civilsociety.

4 Kof Arman, Message to the Business Humanitarian Forum, Geneva, January 27, 1999. http://www.bhforum.ch/pdf/Message%20from%20UN%20Secretary%20General%20Kofi%20Annan,%20Geneva,%20January%2027,%201999.pdf

5 Own translation from German.

6 Quote on the UN web portal of "business and civil society" (www.un.org/issues/civilsociety).

7 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/nation/specials/natureconservancy/

8 Ian Bannon from the World Bank Conflict Resolution Unit in his course "Conflict and Development" at GPPI, George-town University, March 2006.

9 http://www.business-ethics.com/resources/business_ethics_directory.html.

10 Press release: www.global100.org/PR_Global_2007.pdf

11 http://www.globalreporting.org/guidelines/reports/search.asp

12 Press release: www.global100.org/PR_Global_2007.pdf

References

Anheier, Helmut, Marlies Glasius and Mary Kaldor, eds. 2005. Global Civil Society 2004/05. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Banfeld, Jessica, Virginia Haufer and Damian Lilly. 2003. Transnational Corporations in Conflict Prone Zones: Public Policy Responses and a Framework for Action. London: Intenational Alert. [ Links ]

Bennett, Juliette. 2001. Business in Zones of Conflict: The Role of the Multinational in Promoting Regional Stability. New York: International Peace Forum. [ Links ]

Czempiel, Ernst-Otto. 2002. Weltpo-litik im Umbruch : die Pax Americana, der Terrorismus und die Zukunft der internationalen Beziehungen. Munich: C. H. Beck. [ Links ]

Edwards, Michael. 2004. Civil Society. Malden: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Fort, Timothy L. and Cindy Schipani. 2004. The Role of Business in Fostering Peaceful Societies. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hyden, Goran. 1998. Building Civil Society at the Turn of the Millennium. In Beyond Prince and Merchant: Citizen Participation and the Rise of Civil Society, ed. John Burbidge. New York: Kumarian Press. [ Links ]

Kakabadse, Nada K, Cécile Rozuel and Linda Lee-Davies. 2005. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stakeholder Approach: A Conceptual Review. International Jornal for Business Governance and Ethics 1 (4): 277-302. [ Links ]

Krauss, Clifford. 2006. Canada to shield 5 million forest acres. New York Times, February 7. [ Links ]

Iritani, Evelyn. 2005. From the streets to the inner sanctum. Los Angeles Times, February 20. [ Links ]

Mercer Investment Consulting. 2006. Perspectives on Responsible Investment: A Surveuy of U.S. Pension Plans, Foundations and Endowments, and Other Long-Term Saving Pools. New York: Mercer Investment Consulting. [ Links ]

Nelson, Jane. 2000. The Business of Peace: The Private Sector as a Partner in Conflict Prevention and Resolution. London: The Prince of Wales Business Leaders Forum, International Alert, Council on Economic Priorities. [ Links ]

Ramonet, Ignacio. 1999. The year 2000. Le Monde Diplomatique English Edition, December. [ Links ]

. 2000. A new dawn. Le Monde Diplomatique English Edition, January. [ Links ]

Stanwick, Sarah D. and Peter Stanwick. 2005. Are Environmental Concerns Related to Entrepreneurial Growth?: An Examination of the 100 Fastest Growing US Companies. In Making Ecopreneurs: Developing Sustainable Entrepreneurship, ed. Michael Schaper. Burlington: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Tönnies, Ferdinand. 1972. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellscaft. Originally published in Leipzig: Füs, 1887. [ Links ]

Vassilikopoulou, Aikaterini and George J. Siomkos. 2005. Clustering Consumers According to Their Attitudes on Corporate Social Responsibility. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics 1 (4): 317-328. [ Links ]

Yakovleva, Natalia. 2005. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Mining Industries. Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate. [ Links ]